-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

John Regan, Semantic change and knowledge transmission: Some case studies in the distribution of words in ECCO, Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, Volume 37, Issue 4, December 2022, Pages 1141–1156, https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqab035

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This article attempts to make good on the affordances of lexical co-association to investigate semantic change in the British eighteenth-century corpus, mindful of the theories of knowledge that have been presented in an adumbrated state above. Pulling back to enquire into the whole of the eighteenth-century printed corpus, and designing tools fit for apprehending and making sense of such a large, impersonal, non-individual view, will result in a complementary picture of how knowledge was structured and transmitted in the eighteenth century compared with individualistic or ‘great man’ narratives of the history of ideas. Taking the eighteenth-century corpus as a field of enquiry (even in light of its various well-known limitations and inherent biases) results of course in a virtually total loss of granularity at the level of close reading, and a consequent turn away from individual texts written by individual people. But what replaces this is the ability to reconstitute structures of semantic expression from that time that are unexaminable at the level of the sentence and the paragraph, the chapter, and the book. As will be demonstrated, we may now make visible the printed, common, and possibly ‘public’ or social structures of meaning. This article’s field of enquiry is the vast common printed semantic storehouse, as opposed to what is laid down by single authors in clauses, sentences, and chapters.

As theories of human progress proliferated in the anglophone philosophical histories of the later eighteenth century, emphasis was repeatedly placed on the human capacity to move from particular experiences and sensations, to generalizing thought. The human ability to abstract from momentary experiences, to form complex cognition from these, and to communicate general knowledge about them to others through language, was presented in philosophical histories as a key factor separating man from the ‘brutes’ or ‘savages’. Scottish stadial historian Dugald Stewart was one among many theorists who depicted the human capacity for generalizing knowledge and the transmissive power of language as a driver of human improvement:

This boundary [between savage and modern man] is drawn by the capacity of artificial language, which none of the brutes possess even in the lowest degree. They possess, indeed, natural signs, and the power of understanding their meaning, when employed by their own species; but they discover no marks whatever of a capacity to employ arbitrary signs, so as to carry on reasonings by means of them.

Allowing that they possessed all our other faculties, this defect alone would render them totally incapable of forming any general conclusions, and would confine their knowledge entirely to particular objects, and particular events. Nor is this all. The same defect would necessarily confine to each individual his personal acquisitions, and would prevent the possibility of any improvements resulting from the mutual communication of ideas, or from a transmission of knowledge from one generation to another. (Stewart, 1795, p. 403)

This scheme is commonplace in the European Enlightenments. Human intellection is a process of movement from immediate, fleeting impressions to generality and abstractions. The move distinguished modern humankind from the savage preliterary human beings of antiquity, or the unfortunates still living in the remoter, unenlightened parts of the eighteenth-century world.1 What signifies progress is knowledge embodied in linguistic signs that are held in common by a vast number of people. It is precisely the impersonal, the widely communicable, which constitutes knowledge.

It is no coincidence that such an idea gained profound philosophical purchase at a time when the mass media of print was radically refashioning European culture. Knowledge was being transmitted on a mind-bending, hitherto-unexperienced scale. A great deal of thought was suddenly being expended on the ontologies of knowledge and the types of language that were fitting vessels for their communication; what effective and ineffective knowledge transmission looked and felt like. Under conditions set by the emergence of the first-ever mass media in the history of the world, knowledge transmission was a site at which several different claims about human progress could converge.

An intriguing by-product of the newly printed ephemera in which significant portions of human life were being framed and indeed conducted, was an obsession with how knowledge and the signifying vessels for it, effected posterity: how knowledge might survive across generations. As Stewart’s quotation above attests, what might be called knowledge retention, preservation, or knowledge-memory is overwhelmingly the context within which the transmission of knowledge was discussed in the European eighteenth century. This is an important distinction: passing knowledge from generation to generation, rather than among those living coevally, was how the eighteenth century understood ‘knowledge transmission’. As an aside, the noun phrase ‘transmission of knowledge’ is much, less common across Eighteenth-Century Collections Online (hereafter ECCO) than the transitive ‘transmit knowledge’. To transmit knowledge to the next generation was something that one actively did.

Enumerating the many ways in which knowledge transmission in the past was less efficient than in modernity, was a touchstone for theorists constructing a positive narrative of European human development, as in Thomas Burgess’ Essay on the Study of Antiquities from 1781, ‘From the desire, which mankind have had in all Ages of preserving the memory of important and interesting transactions, many expedients were employed to transmit knowledge to succeeding Ages, before the invention of writing. Groves and Altars, Tombs, Pillars, and heaps of Stones, were the representative symbols of past traditions, and memorials to posterity.’ (Burgess, 1781, p. 23). In the busy corner of eighteenth-century letters committed to constructing narratives of human progress, chronological transmission, rather than transmission from place to place, is the major focus. In other words, humanity improves, if knowledge survives and is transmitted: progress as improvement relies upon progress as survival through time.

This was the vision of development propounded by James Burnet, Lord Monboddo and Francis Hutcheson, Thomas Sheridan and Henry Home, Lord Kames, Adam Smith and David Hume; the idea that intellectual progress sees humanity move (through its prehistory and history) from the capacity for merely crudely sensate, individual knowledge possession embodied in natural signs, to a more agile, shareable, essentially social kind of knowledge.

This article attempts to make good on the affordances of lexical co-association to investigate semantic change in the British eighteenth-century corpus, mindful of the theories of knowledge that have been presented in an adumbrated state above.2 Pulling back to enquire into the whole of the eighteenth-century printed corpus, and designing tools fit for apprehending and making sense of such a large, impersonal, non-individual view, will result in a complementary picture of how knowledge was structured and transmitted in the eighteenth century compared with individualistic or ‘great man’ narratives of the history of ideas. Taking the eighteenth-century corpus as a field of enquiry (even in light of its various well-known limitations and inherent biases) results of course in a virtually total loss of granularity at the level of close reading, and a consequent turn away from individual texts written by individual people. But what replaces this is the ability to reconstitute structures of semantic expression from that time that are unexaminable at the level of the sentence and the paragraph, the chapter, and the book. As will be demonstrated, we may now make visible the printed, common, and possibly ‘public’ or social structures of meaning.3 This article’s field of enquiry is the vast common printed semantic storehouse, as opposed to what is laid down by single authors in clauses, sentences, and chapters.

1 Semantic Change in the ECCO Corpus: How a Collective Constructs Meaning

In all forms of linguistic communication, certain words are more likely than others to occur in proximity to one another. One may readily assume that ‘justice’ would be more likely to appear in proximity to the word ‘rights’ in most texts than it would with ‘pineapple’. We can account for this likelihood; quantify what can be thought of as the strength of binding between the words ‘justice’ and ‘rights’. And if we can quantify binding between ‘justice’ and ‘rights’, we may also, by computation, ascertain the strength of binding between ‘justice’ and all of the other words with which it is likely to co-associate in a given corpus of historical texts. Calculations of binding in this article are all the result of a custom-designed measure called distributional probability factor (hereafter dpf).4

Let us begin with an explanatory example. In the 1750s time period of ECCO, the words most likely to appear at a distance of ten words from the word ‘nature’ are in this table. By my calculation, ‘scenery' is the most strongly-associated word with nature in this historical tranche of the corpus. While ‘corrupts' seems to be at the bottom of the list, we should remember that what is in this table are the very-strongest associated words for nature in this part of the corpus.5 A list like this is a window onto the least personal, most general lexical environment in which ‘nature’ was embedded. These lists are descriptive rather than prescriptive: they show how language was used by a great many people, and by extension they begin to reconstruct for us contours of meaning which could not have been generated by any one individual (Table 1).

Associations for the word ‘nature’ in the time period of ECCO 1750-1760, in descending order of strength of association.

| scenery | 3.538835 |

| regenerated | 3.501432 |

| combining | 3.240944 |

| nature | 3.21093 |

| prolific | 3.089264 |

| polygamy | 3.03319 |

| investigation | 3.018566 |

| theories | 3.011382 |

| beings | 2.995735 |

| productions | 2.974939 |

| domain | 2.956154 |

| rural | 2.946253 |

| attainable | 2.908839 |

| imperfection | 2.90279 |

| similarity | 2.895915 |

| nurse | 2.894652 |

| perfections | 2.889148 |

| implanted | 2.88673 |

| mimic | 2.872897 |

| corrupts | 2.86387 |

| scenery | 3.538835 |

| regenerated | 3.501432 |

| combining | 3.240944 |

| nature | 3.21093 |

| prolific | 3.089264 |

| polygamy | 3.03319 |

| investigation | 3.018566 |

| theories | 3.011382 |

| beings | 2.995735 |

| productions | 2.974939 |

| domain | 2.956154 |

| rural | 2.946253 |

| attainable | 2.908839 |

| imperfection | 2.90279 |

| similarity | 2.895915 |

| nurse | 2.894652 |

| perfections | 2.889148 |

| implanted | 2.88673 |

| mimic | 2.872897 |

| corrupts | 2.86387 |

Associations for the word ‘nature’ in the time period of ECCO 1750-1760, in descending order of strength of association.

| scenery | 3.538835 |

| regenerated | 3.501432 |

| combining | 3.240944 |

| nature | 3.21093 |

| prolific | 3.089264 |

| polygamy | 3.03319 |

| investigation | 3.018566 |

| theories | 3.011382 |

| beings | 2.995735 |

| productions | 2.974939 |

| domain | 2.956154 |

| rural | 2.946253 |

| attainable | 2.908839 |

| imperfection | 2.90279 |

| similarity | 2.895915 |

| nurse | 2.894652 |

| perfections | 2.889148 |

| implanted | 2.88673 |

| mimic | 2.872897 |

| corrupts | 2.86387 |

| scenery | 3.538835 |

| regenerated | 3.501432 |

| combining | 3.240944 |

| nature | 3.21093 |

| prolific | 3.089264 |

| polygamy | 3.03319 |

| investigation | 3.018566 |

| theories | 3.011382 |

| beings | 2.995735 |

| productions | 2.974939 |

| domain | 2.956154 |

| rural | 2.946253 |

| attainable | 2.908839 |

| imperfection | 2.90279 |

| similarity | 2.895915 |

| nurse | 2.894652 |

| perfections | 2.889148 |

| implanted | 2.88673 |

| mimic | 2.872897 |

| corrupts | 2.86387 |

But one binding list is only the beginning. Building on this first element we may now, by computation, take each set of terms in which a word is embedded, produce binding lists for all of those words, and visualize the binding connections between many terms. Doing so will reveal the structure of the discursive environments which dominate the ECCO corpus in a range of historical periods. Cross-referencing binding of lists for different terms reveals structured relationships between many words in the lexical record. What overlap is there between what binds to ‘nature’ and ‘decay’? or, how much is shared between what binds to these words and the binding lists for ‘frailty’ and ‘perfection’? How much of what binds to ‘power’ also binds to ‘executive’, ‘plenitude’, ‘legislative’, ‘delegate’, magistrate’, and ‘endued’? Finding the answers to these questions will go some way to identifying patterns in word use that have hitherto remained invisible.6

Before presenting case studies in collective semantic construction in the ECCO corpus, two important factors warrant mention. The first has already been mentioned, but it is significant the ECCO corpus is partial, and that it contains several important biases. Because of these, the claims here about semantic change and potentially, knowledge, primarily relate to the ECCO corpus, rather than to ‘the eighteenth century’ in any wider sense. A corpus is not a culture. Nor is it anything like the sum of language used in a time, nor a total picture of discourse or knowledge. Because the ECCO corpus is a sample of what was published, there can be no definitive claim based upon it for the historical nature of word meanings, collectively produced, in the printed material that was circulating more widely in the British eighteenth century. At points, informed conjectures will be made about the possibility of semantic change and knowledge in British eighteenth-century print more widely. Yet these are all made in a spirit of investigation, mindful of the most-illuminating indictments of the limitations of the corpus, past and present.

The second important prefatory note is that the case studies presented here are not grouped by theme or topic- this is not an article about, say ‘Semantic change in political language in the eighteenth century’ or ‘Vocabularies of beauty in the British corpus’.7 What I have selected to present are interesting cases of lexical distribution that have come to light through years of using computation to explore the corpus. Each of these case studies is intended to turn over new ground, and to facilitate further work trying to understand how semantic change might inform us about semantic change, and potentially the emergence and evolution of epistemes, in the corpus.

And so let us consider some examples from this vast, impersonal storehouse. In the earlier parts of the ECCO corpus, the word ‘market’ most commonly associated with lexis signifying a gathering of traders in specific places: ‘butcher’, ‘farmers’, ‘market-town’, and ‘weekly’ among others. Later in the century of ECCO, however, it accrues another set of associations: ‘commodity’, ‘price’, ‘buy’, and ‘monopoly’. The earlier associations still inflected the word’s meaning, abiding from one end of the corpus century (I will refer to ‘corpus time’) to the other. But word meanings can be capacious. They can accommodate something like ‘a weekly gathering of merchants in a village’ but also ‘the vocabulary of the stock exchange’.

This particular example confronts us with the riven question of when and how two meanings which began as related (say, a market in a town and a stock exchange), end up diverging to the extent that a single word is really being used to mean two different things. And a related but different issue is how a word’s associations tend to be actual and concrete earlier in corpus time (a physical market), and more abstract or ideational (e.g. the marketplace of ideas) as corpus time elapses.8 Historically, as will be shown, the tendency in co-associations is to evolve from the actual to the ideational: from the real to the metaphorical.

Another example of how a word’s meaning was characterized differently at different points in time is the word ‘volition’. This word begins in the eighteenth century most strongly associated with a limited field of lexis characterized by a small vocabulary relating to the inflections of one’s will from moment to moment. In the 1720s tranche of ECCO, there is a limited but ostensibly quite clear semantic field keeping company with the word: ‘agent’, ‘understanding’, and ‘mind’. But at this stage in the corpus’ development, the vocabulary of cognition also keeps company with ‘motion’, ‘power’, ‘force’, and ‘action’. And so mental ‘volition’ shares space around that word with the volition of physical action and movement.

But in the latter decades of the century of ECCO data, the word ‘volition’ is increasingly likely to appear alongside words rooted in anatomy, philosophical theories of mind, and the vocabulary of sensation and affect that was habitual to European aesthetic discourse. The language of physical movement is not as strongly co-associated with the word, and it becomes part of a far more developed and pronounced language relating to theories of mind such as ‘stimulus’, ‘mind’, ‘sensations’, ‘ideas’, ‘knowledge’, ‘consequent’, and ‘motives’ and many more related terms.9 In other words, in the latter decades of ECCO, the word ‘volition’ had become philosophically specialized, in addition to mostly meaning the faculty or power of using one’s will to perform physical acts. This does not mean that it lost its earlier, more banal meaning, but it does suggest that the word began to be used in several related, specialized areas of knowledge after a certain point in corpus time.

Methods in distributional semantics such as lexical co-association are good at discovering the ebb and flow of such lexical contexts in corpora through time. And within this ability to characterize the general semantic associations of a given word in a data set, co-association measures are especially good at showing when a relatively small, clearly defined set of other terms has become particularly strongly associated with a search term in that data. This is of clear relevance to the distributional hypothesis. Given that the distributional hypothesis states that a word’s meaning can be characterized by the company that it keeps, it is relevant that we can, by computation, find out which words are considerably more likely than others to co-associate. Words are of course always surrounded by other words. But if a word is considerably more likely to occur with one tight lexical cluster than with what might be called its general range of semantic associations, then these the markedly strong lexical co-associations for a word should be allotted particular attention.

Now let us allot more sustained attention to one example of semantic change in the corpus. In the earlier decades of ECCO data, 1710–20, one context is particularly apparent within the general range of co-associations for the word ‘attention’. Here we see the strongest co-associations for this word, in rank order with the strongest co-associations at the top (Table 2).

Words most likely to co-associate with ‘attention’ at lexical distance ten in ECCO decades 1710–20 and 1720–30

| ‘Attention’ co-associations, ECCO time period 1700–10 . | ‘Attention’ co-associations ECCO time period 1710–20 . |

|---|---|

|

|

| ‘Attention’ co-associations, ECCO time period 1700–10 . | ‘Attention’ co-associations ECCO time period 1710–20 . |

|---|---|

|

|

Words most likely to co-associate with ‘attention’ at lexical distance ten in ECCO decades 1710–20 and 1720–30

| ‘Attention’ co-associations, ECCO time period 1700–10 . | ‘Attention’ co-associations ECCO time period 1710–20 . |

|---|---|

|

|

| ‘Attention’ co-associations, ECCO time period 1700–10 . | ‘Attention’ co-associations ECCO time period 1710–20 . |

|---|---|

|

|

A vocabulary of reverent church worship emerges: ‘prayers’, ‘devout’, ‘reverence’, ‘prayer’, ‘awe’, ‘hearken’, ‘devotion’, ‘devotions’, and ‘meditation’. In this part of the ECCO corpus, the word ‘attention’ is characterized to a significant degree by words naming and describing the types of attention paid in church. Within this general field, we may articulate particular modes: ‘hearken’, ‘hearers’, and ‘hearing’ suggesting a particular kind of attention along with ‘reading’ and ‘read’. The first signs are that ‘attention’ keeps company with words for listening rather than looking, hearkening to scripture, and reading rather than visually observing. Other words within the general church context make us consider what can be classified as a form of attention: ‘prayers’, ‘prayer’, devotion’, ‘meditation’, and ‘awe’. Is praying a type of attention? Is this how we would think of it now? More importantly, is this sense maintained in the distribution of lexis throughout corpus time? The same questions can be asked of ‘devotion’ and ‘meditation’. Are these forms of attentiveness, or are these words for something which begins with attention in church and which then results in a kind of worshipful transport or transcendence? ‘Meditation’ and ‘awe’ are not necessarily semantically bound to Christian worship, and yet their appearance among a more general church vocabulary suggests a relatedness to that context.

The word undergoes significant semantic change as we move forward in corpus time. Here we see the co-associating lexis for the word ‘attention’ across the last three decades of ECCO data (Table 3).

Words most likely to co-associate with ‘attention’ at lexical distance ten in the ECCO decades 1770–80, 1780–90, and 1790–1800, respectively

| Top twenty words most-likely to co-associate with ‘attention’ distance ten, ECCO time period 1770–80 . | 1780–90 . | 1790–1800 . |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Top twenty words most-likely to co-associate with ‘attention’ distance ten, ECCO time period 1770–80 . | 1780–90 . | 1790–1800 . |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Notes: Here we find one of the few instances of OCR error that was returned in the research for writing this article. It is usually clear what word has been distorted by OCR. The topic of bad OCR and ‘dirty’ or ‘noisy’ data or results is served by a generally very good literature, and I have read widely on the subject. The following chapters, articles, and books have added to my sense of the state of play, and my sense that ECCO is a valid field of enquiry in the context nonetheless: Biber (2018), Hiltunen et al. (2017), Tolonen et al. (2017). Jonardon Ganeri (2017) argues that attention, rather than self, should be the central concept in any attempt to explain the human mind.

Words most likely to co-associate with ‘attention’ at lexical distance ten in the ECCO decades 1770–80, 1780–90, and 1790–1800, respectively

| Top twenty words most-likely to co-associate with ‘attention’ distance ten, ECCO time period 1770–80 . | 1780–90 . | 1790–1800 . |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Top twenty words most-likely to co-associate with ‘attention’ distance ten, ECCO time period 1770–80 . | 1780–90 . | 1790–1800 . |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Notes: Here we find one of the few instances of OCR error that was returned in the research for writing this article. It is usually clear what word has been distorted by OCR. The topic of bad OCR and ‘dirty’ or ‘noisy’ data or results is served by a generally very good literature, and I have read widely on the subject. The following chapters, articles, and books have added to my sense of the state of play, and my sense that ECCO is a valid field of enquiry in the context nonetheless: Biber (2018), Hiltunen et al. (2017), Tolonen et al. (2017). Jonardon Ganeri (2017) argues that attention, rather than self, should be the central concept in any attempt to explain the human mind.

It would be couching the point too emphatically to assert that this indicates that the word ‘attention’ seems to have lost its devotional semantic characterization in the corpus entirely. The words on these lists could of course name or describe the attentions of the worshipper in church. But there has undoubtedly been a dramatic reduction in the explicit lexis of church worship at the tops of its historical co-association lists. It is undeniable that in the last 30 years of ECCO data, there has been a decline in explicit devotional language appearing in lexical contexts with the word ‘attention’.

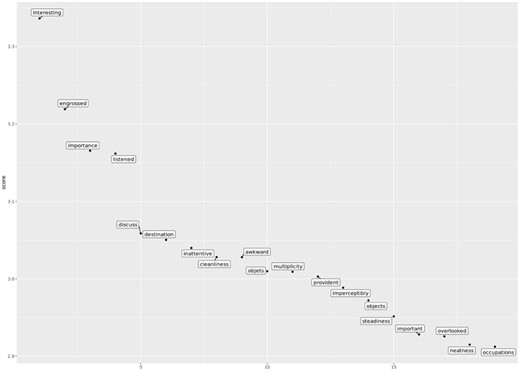

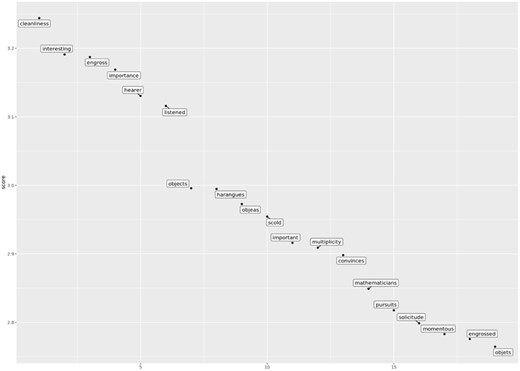

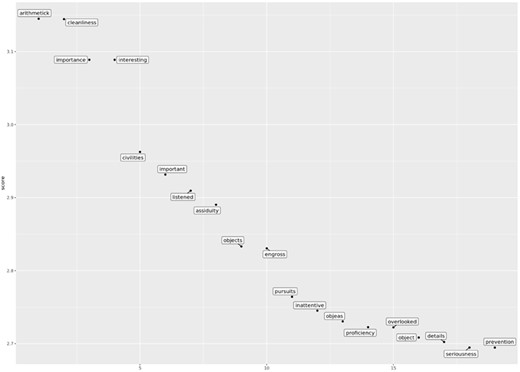

What takes its place? As corpus time elapses, certain other words rise in strength of association with ‘attention’, so that the word ends the century in quite different lexical company to what it started it with. The following three graphs make clear the marked differences in co-association strengths around the word ‘attention’ in the last three decades of ECCO data, respectively, 1770–80, 1780–90, and 1790–1800 (Figures 1–3).

As the historical view moves on to the last decade of ECCO data, we notice that four words co-associate most strongly: ‘arithmetick’, ‘cleanliness’, ‘importance’, and ‘interesting’. A tentative first inference is that as ECCO expands in size in the closing decades of the eighteenth century, ‘attention’ is written about as something which relates to arithmetic and personal hygiene or fastidiousness. Two different types of attention emerge—one a part of intellectual enquiry and another which is a part of a way of living. One interesting difference between these two contexts is that while ‘cleanliness’ and related term ‘neatness’ are features of the co-association lists for ‘attention’ in these three decades of data, ‘mathematic’, and ‘arithmetick’ only inflect the word’s meaning in the later parts of the ECCO data. In other words, ‘cleanliness’ was a key association to ‘attention’ for longer in the ECCO corpus. One line of future enquiry could be how far into the nineteenth century these words retained their lexical association to ‘attention’. If we have witnessed the strength and then decline of the semantic context of attention in church, then perhaps we might also chart the decline of the arithmetical and the tidy, and the rise of other contexts. As ECCO was being put together, selections from the English Short Titles Catalogue were divided into categories, one of which is ‘Religion and Philosophy'. This is certainly the largest category in the first decades of ECCO, which on first inspection appears to explain the religious contexts around this word. But on further investigation, ‘attention' appears with significant frequency in similar contexts in other corpora (for example, the Burney Newspaper Archive) in Britain in the same period.

These data emerge into a fairly well-stocked literature on ‘attention’ in the eighteenth century. In her essay ‘History and Theory of Attention in the Eighteenth Century’, Margaret Koehler expresses a salutary intention: to uncover the historical and cultural conditioning of the word ‘attention’, and to chart the conceptual change happening by investigating uses of the word:

The term “attention” is used ubiquitously but loosely to refer to mental concentration, something that children should pay at school and that we all divide among competing demands. Rarely is attention regarded as a culturally and historically conditioned concept, whose features and domains of operation vary over time, whose historical origins date back farther than we might think, and whose past incarnations might surprise us with both their alien and familiar qualities. (Koehler, 2012, p. 36)

Koehler seeks to correct an overwhelming focus on attention as a psychological issue or problem ‘(1)- by tracing the vigorous discussion and debates around attention during a period that witnessed intense interest in the concept and radical revision of its and (2)- by contending that literary texts—poetry in particular—provide essential documentation of how attention works.’ (Koehler, 2012, p. 36). Her study uses close reading to produce a rich conceptual history of ‘attention’. Nevertheless, virtually none of the semantic inflections of the word ‘attention’ that have been brought to light by distant reading above make their way into that study of the word and concept. This is explicable largely because the ‘vigorous [eighteenth-century] discussions and debates’ that Koehler charts, will not have made any significant mark on the general distribution of lexis in the British corpus. This is not a criticism; the above findings are intended to complement and indeed to enrich the wonderful scholarship that Koehler and others have done in the conceptual history of this word and many others. However, it should be noted that there is, broadly, a disjuncture between semantic contexts that have been judged important to the word and concept ‘attention’ in close reading, and what is emerging here.

Elsewhere, the church context receives some attention, so to speak. Through close praxis, another scholar of ‘attention’, Natalie M. Philips, has found a number of examples of people being paid, in the earlier eighteenth century, to keep people awake in church. She writes of a parish in York who paid a man to ‘wake up nodding parishioners’ and a man named Thomas Pawson is paid in 1711 ‘for awakening those who sleep in church’ (Phillips, 2016, p. 121). In 1725, a man named John Rudge left in his will ‘twenty shillings a year to fee a poor man to go about the church and keep the people awake’ (Ibid). Philips also allots a significant amount of attention to the issues of attention and distraction and sleepiness in Laurence Sterne, and presents some other examples of clergymen given express instructions to hold the attentions of their congregations. These characterizations of how worshipful ‘attention’ might be dissipated do not include any reference to the word-concepts that are present in the earlier co-associations ‘wandring’, ‘interrupt’, and ‘interrupted’. Therefore we might do some more work on the idea that church attention was not only banished by sleep and tiredness but by a more jarring interruption or by the perambulations of the imagination. What I mean by mentioning this semantic disjuncture, is that we might now combine close and distant readings to compare specialized, highly contextually determined readings with a more general picture of how people wrote about the dissipation of attention. The question could be: why is the general characterization that attention is dissipated by the wandering imagination in the distant view, where in these particular cases, fatigue and nodding off is judged to be the main cause?

Supplementary to this general idea for future enquiry is a more specific road that we may go down. Simone Kotva has written powerfully of attention in the context of spirituality, demonstrating that while certain philosophical traditions in history sanction active, effortful practices such as meditation, the concept of grace, for example, diverts the Christian away from such attention, such as it is. What is emerging in the distributive view here, are grounds for an enquiry into effortful attention in the context of the eighteenth-century British church. And so the focus may, in light of these preliminary results, be on the kinds of effort, rather than passive grace, that is written about in early eighteenth-century Britain.

Koehler and Philips provide wonderfully evocative examples of church attention, but really, their paucity highlights the fact that in the evidence that Philips (2016) presents, church appears as a minor precinct amidst a great many other contexts in her book Distraction: Problems of Attention in Eighteenth-Century Literature. That book gives no sense (because such a sense was not sought by the author), that the worship context is key to the semantic definition of the word ‘attention’ in the eighteenth-century corpus. The five pages on which church is references in the book give no impression of the wider penetration of this context in the ECCO corpus in this earlier period. Again, though, it is hoped that lexical co-association has opened up new avenues for further enquiry in the history of the idea of ‘attention’. What is presented here are tentative first steps into the collective construction of ‘attention’ in the early ECCO corpus. Once again it should be made clear that they are not intended to repudiate any prior close analysis, but to add one (admittedly limited) communal generation of knowledge of this semantic field and constituent concepts, to the fine work that has already been done in the conceptual history of ‘attention’.10

Surveying the company that a word keeps through time, as we have done for ‘attention’ and as we did more briefly for the examples in the Introduction, is a crucial way of characterizing meaning. And while these first views onto semantic change are somewhat crude, doing this is certainly a valid, evidentially supported method of assessing the meaning of a word in a given time. We can—indeed we shall—make assertions about semantic change based upon the lexical company that words keep as time progresses. But in addition to this kind of observation, we can subject lexical co-association data to the modes of attention and interpretation that are habitual to corpus linguistics and distributional semantics. These help us to build fine-grained evidential cases about how words were used in the corpus of the eighteenth century, allowing us to make tentative inferences about how meaning is constructed by the authors included in the corpus as a whole. Magnus Sahlgren is cognizant of the fact that while co-association data effaces the kinds of sense that are made in grammatical sentences, the distributional researcher should cleave to ‘linguistic knowledge’ to ascertain word meanings:

Linguists that encounter distributional models tend to frown upon the lack of linguistic sophistication in their definitions and uses of context. We are, after all, throwing away basically everything we know about language when we are simply counting surface (co-) occurrences. Considering the two different types of distributional models discussed in the previous sections, the paradigmatic models are arguably more linguistically sophisticated than the syntagmatic ones, since a context window at least captures some rudimentary information about word order. But why pretend that linguistics never existed — why not use linguistic knowledge explicitly? (Sahlgren, 2008, p. 47)

Why not indeed. Linguistically sophisticated concepts such as paradigmatic versus syntagmatic relations between words allow us drill down into what words mean in given historical periods of the corpus. Other such tools are equally helpful, such as thinking about whether words in a certain distribution are in antonymic or meronymic relation. Used judiciously, linguistic–analytical tools are remarkably useful in investigating how words related.

Before moving on to our next case study, let us broach the model of relations between lexical associations and word meanings that underpins this research. These relations are proposed here in the form of a heuristic: the ‘distributional hypothesis’.11 This posits that word meanings are characterized by the lexical contexts in which they appear. This descriptivist position has been phrased in many different ways since its inception in the 1950s in the work of Zelig Harris. The best-known progenitor of the theory was John Rupert Firth who posited that ‘the complete meaning of a word is always contextual, and no study of meaning apart from context can be taken seriously.’ (Firth, 1957, p. x).12 More recently Patrick Pantel has posited that ‘words that occur in the same contexts tend to have similar meanings’ (Pantel, 2005, p. 126).13 Perhaps most germane to this study is Sahlgren’s formulation: ‘The main point of this hypothesis is that there is a correlation between distributional similarity and meaning similarity, which allows us to utilize the former in order to estimate the latter’14 (Sahlgren, 2008, p. 33). There is some question over whether we may understand the hypothesis to imply a kind of agency: whether contexts determine word meanings as well as simply indicating what that meaning is. Arguably, this cannot be answered definitively. Yet in addressing the issue we may open up some useful avenues for further exploration.

For many researchers in the field, the ‘distributional hypothesis’ entails an obvious question or problem. This is to what extent is the psychology and language use of individual people influenced by many, many word uses across various media in a given time? Or, how is a single person’s knowledge shaped by the collectively produced flow of language, propagated in print? As numerous studies have shown, it is very difficult to toggle meaningfully between a distributional analysis of many words, and a secure sense of how individual human beings acquired word meanings and possessed knowledge.15 The relation of knowledge acquisition or justified belief by individuals to social or collective knowledge, is not clear. This is the central field of enquiry in Social Epistemology.

But as aforementioned we are not concerned with the question of knowledge acquisition and transmission by individuals. Instead, this is an enquiry into word meanings and knowledge as products of millions of word uses, across many publications in a British corpus, viewed diachronically. The object of enquiry is not the individual or her works: it is the whole historical data set, with the flaws of that set taken into consideration. This article begins to investigate the vast, impersonal storehouse of word meanings and knowledge produced by the corpus’ constituent authors.

2 Semantic Change for the Word ‘Protestant’

Large corpora—even those as imperfect and predisposed as ECCO—are particularly well-suited to enquiries into the phenomenon of othering (Baleria, 2019). Othering is the phenomenon of a community of people assuming that they have established or normative identities, and feeling that certain groups are intrinsically excluded from or inferior to those identities. The majority of texts which were digitized to produce the ECCO corpus were written by men and, broadly, these texts were written by men who would have identified as Protestant. And so the ECCO corpus is a useful resource if we wish to identify how, and to what extent, these normative or conventional British identities (among others of course) have left their mark in how language was used. Looking at the strongest co-associations for the words ‘women’ and ‘Protestant’ in two historical tranches of the ECCO corpus, we discover two different kinds of meaning formation (Table 4).

In the left column, words most likely to co-associate with ‘women’ at lexical distance ten in ECCO decade 1710–20. In the right-hand column, words most likely to co-associate with ‘protestant’ in texts listed as having been published in the 1750s, included in the corpus.

| ‘protestant’ ECCO time division: 1750s . |

|---|

|

| ‘protestant’ ECCO time division: 1750s . |

|---|

|

In the left column, words most likely to co-associate with ‘women’ at lexical distance ten in ECCO decade 1710–20. In the right-hand column, words most likely to co-associate with ‘protestant’ in texts listed as having been published in the 1750s, included in the corpus.

| ‘protestant’ ECCO time division: 1750s . |

|---|

|

| ‘protestant’ ECCO time division: 1750s . |

|---|

|

Beginning with the word ‘Protestant’, we notice that this list of co-associations contains several words for the perceived opposite of the search word. In a list of the twenty most-strongly associated words in the corpus, the antonyms ‘papist’, ‘popish’, ‘popery’, ‘papists’, ‘catholics’, ‘romish’ ‘catholic’, ‘catholick’, and ‘jesuit’ constitute a significant presence. And so a list like this forces us to broach the question of how meaning is constructed according to the distributional hypothesis if the co-associating lexis is mainly antonymic. Words with similar meanings may tend to occur in similar lexical contexts, but what does semantic similarity mean if the words surrounding a noun in a given lexical context are types of antonyms for that word? How can a word’s meaning be constituted by its perceived opposites?

To answer this question, we must again recognize that co-association tools, and the distributional hypothesis in general, are concerned with describing how meaning was constructed by uses, rather than by prescription. To once again state the proposition which was first stated in relation to data for the word ‘attention’, word meanings are produced as much by how these words were employed in the general flow of communication across media, as they were by their definitions in dictionaries. The adjective and noun represented by the word ‘Protestant’ had meaning—that is they evidently had a use in discourse—precisely because they denoted not only Protestantism as such, but even more strongly, that which contradistinguished it in the British publications that constitute this eighteenth-century corpus. When authors used the word, its usefulness resided in large part in how it co-associated with the language of the Catholic other. The meaning of the word ‘Protestant’ in the 1750s Britain could of course be given in the form of a definition invoking the history of Lutheranism and the reformationist histories of northern European states in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, to name only a few relevant contexts. But the ways in which the word was used by many authors and the lexis surrounding it (which is what the lexical co-association measure is showing us) are a determining what this word meant. The lexical co-association measure has demonstrated that for many authors in this corpus the word ‘Protestant’ had a very particular meaning: it meant ‘that which was not Catholicism’, where Catholicism was represented most frequently in a set of demotic, derogatory nouns in this data set.

Imagine the counterfactual. It would have been equally feasible and predictable for the word ‘Protestant’ to have co-associated most strongly in the corpus with some of the synonymic and near synonymic words that occur further down its co-association list: ‘Protestant’, ‘Protestants’, ‘Lutheran’, ‘Lutherans’ or ‘Hanover’. In other words, ‘Protestant’ could have been associated most strongly with the parts, places, and people of the reformed church. But the evidence shows that as it was used by the authors whose texts constitute ECCO in this time frame, this word’s meaning was not simply something like ‘the institutions, leading people and tents of the reformed church’. Its meaning is something other than ‘the contents of Protestantism’. Its meaning was constituted at least as much, if not arguably more, by its being a word that is characterized by its semantic opposites. It may seem paradoxical, but the meaning of a word can reside in such antonymic relations. A word can have meaning because it denotes that which it is not. In broaching this question of ‘semantic similarity’, Sahlgren provides the most succinct summation of the worth of the distributional approach in pursuing descriptive evidence of word use in large corpora:

… as Padò & Lapata note, the notion of semantic similarity is an easy target for criticism against distributional approaches, since it encompasses a wide range of different semantic relations, like synonymy, antonymy, hyponymy, etc. Thus, it may seems as if the concept of semantic similarity is too broad to be useful, and that it is a liability that simple distributional models cannot distinguish between, e.g. synonyms and antonyms.

Such criticism is arguably valid from a prescriptive perspective where these relations are a-priorily [sic] given as part of the linguistic ontology. From a descriptive perspective, however, these relations are not axiomatic, and the broad notion of semantic similarity seems perfectly plausible. (Sahlgren, 2008, p. 37)16

The descriptive view, provided bottom-up by many users of language, is undeniably more capacious than a single definition. As recognized above, semantic similarity is a conception of meaning in which antonymic relations constitute rather than negate meaning.

Building on this view, we can gain more information about the meaning of this word in the corpus by remaining alive to the linguistic features that are under consideration. As already noted ‘Protestant’ can be used as an adjective and as a noun. Most of the antonymic words already listed, ‘papist’, ‘romish’, ‘catholic’, ‘catholick’, and ‘jesuit’, are adjectives and nouns also. This grammatical similarity tells us something about meaning. The strongest associating words for ‘Protestant’ could, without loss of grammatical propriety, substitute the search word in sentences. In terms of grammatical rules, all of these words could be substituted for one another in linguistic expressions. The co-associating lexis for ‘Protestant’ listed above could all fill in the blank space in a sentence such as ‘In religious terms the majority of the country’s population in the early eighteenth century was ________.’ In distributional semantics, these relations between ‘Protestant’ and these co-associating words are designated ‘paradigmatic’. We need only note that words being in paradigmatic relation do not mean that they all mean the same thing as such, but that these words have in common the work that they do in communication. This is, they share a function. This is one way in which human beings perceive and construct meaning: by recognizing the functions that parts of language perform, and by understanding that other words could have been chosen in place of those that are on the page performing those functions. For example, in the sentence ‘Without a grounding in chemistry medical students will struggle’, some of the semantic content of this declarative statement resides in the fact that the academic or scientific discipline ‘Chemistry’ is used and that it could be substituted by ‘Physics’ or ‘Biology’, ‘Mathematics’ or ‘Data Science’. Paradigmatic relations in language mean that readers, whether they are conscious of it or not, will have some sense of the choice of one signifying word over another. Language theorist Daniel Chandler articulates this as an important part of word meaning: ‘Semioticians often focus on the issue of why a particular signifier rather than a workable alternative was used in a specific context: on what they often refer to as “absences”’ (Chandler, 2020). John Fiske argues that in any text ‘the meaning of what was chosen is determined by the meaning of what was not’ (Fiske 1982, p. 62).

We have already noted that the contents of Protestantism such as Lutheranism were not ‘chosen’ in the sense that they were not the most-strong co-association for this word in this data set. But what else ‘was not chosen’ by the authors included in ECCO? For one, a more polite language for the church of Rome such as ‘Catholic’, ‘Pontiff’, ‘Rome’, ‘Catholics’, or ‘Eucharist’ has not been ‘chosen’ by the majority of authors in this corpus in this time period. It is important to the meaning of the word ‘Protestant’ that the demotic ‘papist’, ‘popish’, and ‘Romish’ characterized it rather than formal or polite terms. It is not at all surprising that derogatory words were used for Catholicism in the ECCO corpus. What is more notable, is that this derogatory vocabulary is markedly more likely to co-associate with ‘Protestant’ than any of the formal terms listed above.

These two factors of co-association, the fact that antonyms are more strongly associated with this word than antonyms, and that colloquial derogatory nouns and adjectives are more likely to contextualize this word, are crucial part of this word’s meaning in this corpus in this time period. To stay with Chandler’s idea of what is ‘chosen’, they are words that are at once grammatically substitutable and entirely semantically oppositional at the same time. When ‘Protestant’ associates with ‘papist’ and ‘romish’ it is clear that the word’s meaning is constituted by what it is perceived not to be, where what it is not to be has been derogated in terms.

One very tentative inference at this stage could be that the paradigmatic relation of ‘Protestant’ to its associated lexis, reflects the phenomenon’s real-world social and political functions. ‘Protestant’ is self-evidently a word for something which is intended to replace something else, just as in paradigmatic lexical relations one word must be replaceable by another without loss of grammatical form. The word can supplant other things just as a reformed church may supplant the Roman church. In this sense, the word’s meaning and linguistic function both mirror the religious tumult of the age. But again it is worth remembering that what is supposed to be displaced, according to this distributional data, is the ‘Papist’ and ‘Romish’ church. Intrinsic to this set of co-associations is the sense that the old institutions should be signified and conceptualized in a critical demotic. And so the word does not only occur in contexts which could be characterized as something like ‘that which is not Protestant’, but ‘words largely of the same type derogating Catholicism and Catholics in a demotic’. The word ‘protestant’ is given meaning by co-associating with words that perform essentially the same grammatical function as it does in sentences: these features constitute and determine meaning.

Words do not necessarily co-associate with others that are in paradigmatic relations with them. The word ‘nature’, for example, in the ECCO time slice 1730–40, co-associates with the words ‘implanted’, ‘partakes’, ‘repugnant’, partakers’, and ‘immutable’, none of which are in paradigmatic relation to the search term. These are different word types and could not be substituted for ‘nature’ in sentences. If we imagine that the most strongly associated lexis for ‘Protestant’ was, similarly, not in paradigmatic relation but a selection of other feasible co-associated words such as ‘superstitious’ or ‘theses’ or ‘Roman’, this would be a sign that a different kind of sense was being made with the word ‘Protestant’. What would be lost would be an emphasis on the phenomenon’s fitness to replace the old institutions. The corpus presents a particular, distinctive semantic construction here, and it would be fascinating to investigate whether this construction obtained more widely in the majority of texts published in the British eighteenth century.

Let us take stock of the parts of meaning that are becoming clearer with each piece of data and analysis that is being enumerated here. The meaning of the word ‘Protestant’, in addition to historical definitions extant from the time, was also inflected, given meaning, by three related factors. The first was that it was used as a word among several others of the same type: writers used, and readers encountered, the word ‘Protestant’ as a word among several others all functioning identically, in grammatical terms. Secondly, the grammatically identical words were all antonyms. Thirdly, these antonyms were derogatory and colloquial terms. And so here, we can feel the benefit of the polysystemic possibilities of distributional semantics. We have come to a better understanding of the extent of the word’s antonymic lexical armature in the corpus, its demotic embeddedness, and its grammatical interchangeability with even the most strongly antonymic terms in its lexical orbit. These are parts of the meaning of this word that would have remained undiscovered without the use of a digital measure of lexical co-association.

Let us conclude by pausing and reflecting on the examples we have viewed, ‘attention’, ‘Protestant’. What has become apparent in these cases is that the constituency of authors whose publications were digitized to produce ECCO, collectively but without organization or consensus, constructed meanings which could be described as being adjacent or tangential to the received, formal definitional lives of these words. A definition of ‘attention’ provided by a single person or authority in Britain in the early eighteenth century may well not have included reference to the church, or the act of listening. A definition of ‘Protestant’ would most likely not have included the demotic language of the Catholic imaginary other. A definition of ‘women’ would most likely not have mentioned bracelets or Mary Magdalen. And so we are faced with communal constructions of meaning (remembering that these are only by the authors included in ECCO) that are in opaque relation to prescribed or received senses of these words. Meaning produced in these many uses of the representational forms of language, looks very different to meaning produced with the expressed aim of providing legal definition. This fault line, between meaning produced by many uses and by definition, invokes the issue of the autonomy of knowledge: who sets the limits of what is knowable and how much control anyone has over this. The issue of the autonomy of communal knowledge is of particular relevance to a period of British commercial history in which more people had access to published writing than ever before.

Visualization of co-association strengths for the word ‘attention’, lexical distance 10, ECCO tranche 1770–80. The higher up and further to the left words are on these graphs, the more strongly associated they are to the search term ‘attention’ in each historical tranche of ECCO, 1720–30, 1750–60, 1790–1800. These graphs are quite typical of the strengths of association for words in the corpus in that they show some very strongly associated lexis, and then further down the list, a more general picture of words that were likely to co-associate with the word

Visualization of co-association strengths for the word ‘attention’, lexical distance 10, ECCO tranche 1780–90

Visualization of co-association strengths for the word ‘attention’, lexical distance 10, ECCO tranche 1790–1800

References

Endnotes

This is of course an adumbration of the discourse. Stewart (1795) apprehended the two stages of abstraction: first the abstraction from natural to arbitrary signs, and then the abstraction from arbitrary signs denoting concrete things to arbitrary signs denoting abstract concepts.

The co-association tool used in this article, which among other features contains two tabs allowing users to visualize co-association results, can be found at <https://concept-lab.lib.cam.ac.uk/shiny/viewers/viewer-current/>. This interface was designed primarily by Paul Nulty, in collaboration with the author, Peter de Bolla, Ewan Jones, and Gabriel Recchia, at the Cambridge Concept Lab between 2014 and 2020.

The word ‘public’ of course deserves some qualification. The authors of the texts which have been digitized and which constitute ECCO, were at once removed from the public, and yet were refashioning what the public sphere might include. Across the century, printed materials became more and more central to a public discourse: it can be asserted that public life was in some sense carried out in print, even if those publishing still constituted a tiny minatory relative to the population.

This ‘observed’ number of co-associations is then compared with an ‘expected’ baseline. This baseline is in fact an artificially contrived comparator in which no word is more or less likely to co-associate with any other word. In other words, the actual binding between words in natural language is compared with an artificial ‘expected’ number in which all terms in the corpus are randomized, to calculate strength of binding between words.

These lexical co-associations are of course produced and inflected by the kinds of epistemic space that authorship, editing, and commercial publishing fostered. This is to say that what we are observing here is language use in a printed domain dominated by an educated authorship and relatively moneyed demographic. This authorship and demographic prioritized certain semantic domains for words’ preservation and transmission, and these are likely to vary dramatically to how these words were situated in the eighteenth-century Anglophone world at large, across socio-economic strata. We may acknowledge this much without impugning these lists, and yet we must keep in mind that they do not represent fully-established ‘public’ usage.

This method is explained in much greater detail in de Bolla et al. (2019).

I assume virtual equivalence between word meanings and concepts. In this respect my position is fundamentally different to that taken by my colleague Professor Peter de Bolla in his wonderfully insightful book The Architecture of Concepts: The Historical Formation of Human Rights (de Bolla, 2013).

The development of publications in successive years, and their allocation in these years as they are digitally subsumed into the data set ECCO, will be referred to as ‘corpus time’. This unusual phrase is intended to recognize that the year 1770 in ECCO, for example, is a different object or phenomenon or concept to the year 1770 in general. ECCO is a sort of simulacrum of historical development: an artificial digital history of publication.

On computational searches for meaning in corpora, previous work has tended to investigate small and more recent corpora, such as Scott (2001).

Crary (1999) is an evocative realization of the particular conditions of media, attention, and attention to media between 1880 and 1905.

Within the vast literature on context and word meanings in distributional semantics, I have found the following articles and chapters particularly illuminating: Evans (2006), Fauconier (1994), and Fillmore (1977). One problem which attends all of this worthwhile reading, however, is the fact that it all seeks to explore the cognitive realism of the individual subject. There is often an important slippage, however, between the theoretical reading I have done, and this study’s topic of enquiry: collective knowledge.

My reading of Firth and John Sinclair has been accompanied and informed by Lèon (2007).

Sahlgren (2008) is indebted to the now-canonical text by Rubenstein and Goodenough (1965).

‘Semantic similarity’ is a complex concept. It encompasses antonymic as well as synonymic relations between words, for example.

My understanding of the implications of collocation for meaning has been refined by reading Church and Hanks (1990), Müller (2008), and Philip (2011).

Padò and Lapata (2003, 2007) to which Sahlgren (2008) refers are rich resources for anyone wishing to trace the procedures of turning natural language data into semantic space models.