-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Alain M Schoepfer, Stevie Olsen, James Siddall, Eilish McCann, Siddhesh Kamat, Kinga Borsos, Angela Khodzhayev, Amr Radwan, Tiffany Pela, Juby Jacob-Nara, Sarette T Tilton, Ryan B Thomas, Burden of eosinophilic esophagitis in adult and adolescent patients: results from a real-world analysis, Diseases of the Esophagus, Volume 38, Issue 2, April 2025, doaf024, https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/doaf024

Close - Share Icon Share

Summary

Real-world data on the impact of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) in patients are limited. This study assessed clinical characteristics, healthcare resource utilization (HCRU), symptoms, comorbidities, and quality of life (QoL) of EoE patients.

The multicountry cross-sectional survey, Adelphi EoE Disease Specific Programme™, collected physician and patient-reported data on clinical characteristics, HCRU, symptoms, comorbidities, and QOL of EoE patients with past/current proton pump inhibitor use and ongoing dysphagia-related symptoms (September to December 2020) at study entry.

Physicians provided clinical characteristics, symptom, comorbidity, and HCRU data for 412 patients (12–17 years: 8%; ≥18 years: 92%); and 161 of these patients (12–17 years: 6%; ≥18 years: 94%) provided symptom and QOL data. Of the 412 patients, 67% were male, with a mean (SD) age of 37.0 (15.3) years. Overall, 74% of patients were currently being treated with corticosteroids (12–17 years: 88%; ≥18 years: 73%); 25% of patients had a history of esophageal dilations (12–17 years: 19%; ≥18 years: 26%); and 30% of patients had EoE-related emergency room visit (12–17 years: 31%; ≥18 years: 30%) in the last year. Among the 161 patients, heartburn (69%) was the most commonly reported symptom; the greatest negative impacts on QOL were reported for dysphagia-related anxiety, social activities involving food, and maintaining friendships (EoE Impact Questionnaire scores [1–5, low to high impact]: 1.6–2.2 for both age groups).

EoE patients continued to experience disease burden despite receiving treatment, highlighting the high unmet need for effective disease management in this population.

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a type 2 inflammatory disease that results in chronic, progressive, and functional abnormalities in the esophagus.1–3 EoE is characterized by symptoms including dysphagia and associated food impaction, heartburn, vomiting, and chest and stomach pain. These symptoms may negatively impact patients’ quality of life (QOL), productivity, emotions, and social activity, particularly in patients with severe symptoms.2,4 Epidemiological data for EoE comes primarily from studies conducted in North America and Europe, with recent incidence estimates ranging from 5 to 10 cases per 100,000 and prevalence estimated to be 57 per 100,000 persons.5,6 Furthermore, global EoE incidence rates appear to have been rising in recent decades.7

Clinical guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association and the Joint Task Force on Allergy-Immunology Practice Parameters currently recommend pharmacological agents such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), swallowed corticosteroids, and/or an elimination diet, with guidelines leaving the choice of first-line treatment to the prescribing physician.1,8 Novel therapeutic approaches include dupilumab, which has been demonstrated to be an effective and safe treatment option for adult, adolescent (aged ≥12 years), and pediatric (aged ≥1 year) patients with EoE.9,10 These clinical findings led to the US and European Union approvals of dupilumab for adults and adolescents in 2022 and for children (US only) in 2024; at present, dupilumab remains the only approved biologic treatment for EoE in the US and Europe.11–13 In addition, post hoc analyses of clinical study data demonstrated that dupilumab improves health-related QOL and reduces symptom burden in patients with EoE, particularly in relation to dysphagia.14 Esophageal dilation, the mechanical widening of a narrowed section of the esophagus, can be considered in patients with esophageal strictures or risk of food impaction; it may provide symptom alleviation but does not alter the underlying eosinophilic inflammation or progression of disease and therefore additional medical and/or dietary treatment prior to, or alongside, dilation is required.15 Although rare, esophageal dilations may lead to esophageal perforation.15,16 As EoE is characterized by type 2 inflammation, patients may also have other type 2 inflammatory-associated diseases such as asthma, atopic dermatitis (AD), and allergic rhinitis. Similarly, patients with asthma, AD, or allergic rhinitis are at increased risk of developing EoE.17,18

Data showing the impact of EoE on patients’ QOL in the real-world setting are limited. The aim of this study was to describe the clinical characteristics, therapies received, healthcare resource utilization (HCRU), symptom burden, and impact of EoE on QOL in patients with the disease who receive nonbiologic therapies across multiple countries.

METHODS

Study design

This analysis collected real-world data through the Adelphi Real World EoE Disease Specific Programme™, a multicountry (US, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, UK), cross-sectional survey of EoE-treating physicians and their consulting patients. Physicians reported data for up to 12 consecutive patients with EoE from September to December 2020 by completing a patient record form (PRF). Following PRF completion, physicians received a monetary reimbursement according to fair market research rates. Ethics approval was granted by the Western Institutional Review Board (protocol number: AG8830; study number: 1288424). Physician-reported patient data were included for patients aged ≥12 years with a confirmed diagnosis of EoE, previous and/or current PPI treatment (with or without swallowed corticosteroid treatment), and ongoing symptoms of dysphagia, choking on food, or food impaction. Treating physicians-reported clinical characteristics, symptoms, current treatment, HCRU, and comorbidities of patients with EoE. Patients (or their caregivers where required, i.e. for patients aged <18 years) were also invited to complete a questionnaire on the frequency of 5 EoE symptoms (chest pain, stomach pain, burning feeling in chest [heartburn], food or liquid coming back up into throat, vomiting). Patients (or their caregivers) were asked how many days they/their child experienced each symptom in the past 7 days. In addition, patient QOL was assessed using the 11-item EoE Impact Questionnaire (EoE-IQ), which measures the emotional, social, work/school productivity, and sleep-related impact of EoE over a 7-day recall period, on a scale of 1 (‘no impact’) to 5 (‘extremely high impact’).19 Mean EoE-IQ scores (ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater QOL impact) were calculated for each question of the EoE-IQ, in addition to the total average EoE-IQ score derived from all questions. Results for all outcomes were stratified by age group (adolescents aged 12–17 years and adults aged ≥18 years).

Statistical methods

This study presents a descriptive analysis. Categorical variables were summarized by frequency and percentage; continuous variables were summarized by mean (SD).

RESULTS

Characteristics of participating physicians and patients

Treating physicians (n = 189) completed PRFs for 412 patients (12–17 years: 32 [7.8%]; ≥18 years: 380 [92.2%]). Physicians completing the PRFs were mostly gastroenterologists (89.9%) followed by allergists (10.1%), and on average, almost half of these physicians practiced in a public hospital (46.8%), 25.7% in a private office, 14.6% in a public office, 12.8% in a private hospital, and 0.2% in other clinical settings. Most of the 412 patients were male (66.7%), with a mean (SD) age of 37.0 (15.3) years (Table 1). Overall, mean (SD) time since EoE diagnosis was 32.1 (43.2) months and was slightly longer for patients aged 12–17 years (35.1 [31.2] months) than for those aged ≥18 years (31.8 [44.1] months; Table 1). In addition, 161 (12–17 years: 10; ≥18 years: 151) of the 412 patients participated in an optional self-reported questionnaire, with 14 forms being completed by the patient’s caregiver (10 patients aged 12–17 years and four patients aged ≥18 years had their form completed by their caregiver; Supplementary Table S1). In this subgroup of 161 patients, most participants were male (71%), with a mean (SD) age of 38.5 (14.9) years.

Baseline patient demographics and clinical characteristics (physician reported)

| . | All (N = 412) . | 12–17 years (n = 32) . | ≥18 years (n = 380) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), years | 37.0 (15.3) | 15.5 (1.7) | 38.8 (14.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 275 (66.7) | 21 (65.6) | 254 (66.8) |

| Mean BMI (SD), kg/m 2 | 24.5 (3.6) | 21.8 (3.2) | 24.8 (3.6) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | n = 408 | n = 32 | n = 376 |

| White | 353 (86.5) | 22 (68.8) | 331 (88.0) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 19 (4.7) | 4 (12.5) | 15 (4.0) |

| African American (US) | 10 (2.5) | 1 (3.1) | 9 (2.4) |

| Afro-Caribbean (EU) | 7 (1.7) | 1 (3.1) | 6 (1.6) |

| Asian-Indian subcontinent | 6 (1.5) | 3 (9.4) | 3 (0.8) |

| Asian-other | 5 (1.2) | 1 (3.1) | 4 (1.1) |

| Mixed race | 4 (1.0) | 0 | 4 (1.1) |

| Middle Eastern | 3 (0.7) | 0 | 3 (0.8) |

| Other | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Mean time since diagnosis (SD), months a | 32.1 (43.2) | 35.1 (31.2) | 31.8 (44.1) |

| Mean time since current pharmaceutical treatment initiation (SD), months | 17.3 (21.3) | 23.8 (22.6) | 16.7 (21.2) |

| History of dilation due to EoE, n (%) | 104 (25.2) | 6 (18.8) | 98 (25.8) |

| EoE-related ER visit in the 12 months prior to data collection, n (%) | 122 (29.6) | 10 (31.3) | 112 (29.5) |

| Mean number of EoE-related ER visits (SD) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) |

| History of elemental formula diet, n (%) | 31 (7.9) | 7 (21.9) | 24 (6.6) |

| Time on elemental formula diet (SD), weeks | 67.2 (109.3) | 75.5 (125.5) | 65.7 (107.3) |

| History of elimination diet, n (%) | 80 (19.9) | 10 (31.3) | 70 (18.9) |

| . | All (N = 412) . | 12–17 years (n = 32) . | ≥18 years (n = 380) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), years | 37.0 (15.3) | 15.5 (1.7) | 38.8 (14.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 275 (66.7) | 21 (65.6) | 254 (66.8) |

| Mean BMI (SD), kg/m 2 | 24.5 (3.6) | 21.8 (3.2) | 24.8 (3.6) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | n = 408 | n = 32 | n = 376 |

| White | 353 (86.5) | 22 (68.8) | 331 (88.0) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 19 (4.7) | 4 (12.5) | 15 (4.0) |

| African American (US) | 10 (2.5) | 1 (3.1) | 9 (2.4) |

| Afro-Caribbean (EU) | 7 (1.7) | 1 (3.1) | 6 (1.6) |

| Asian-Indian subcontinent | 6 (1.5) | 3 (9.4) | 3 (0.8) |

| Asian-other | 5 (1.2) | 1 (3.1) | 4 (1.1) |

| Mixed race | 4 (1.0) | 0 | 4 (1.1) |

| Middle Eastern | 3 (0.7) | 0 | 3 (0.8) |

| Other | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Mean time since diagnosis (SD), months a | 32.1 (43.2) | 35.1 (31.2) | 31.8 (44.1) |

| Mean time since current pharmaceutical treatment initiation (SD), months | 17.3 (21.3) | 23.8 (22.6) | 16.7 (21.2) |

| History of dilation due to EoE, n (%) | 104 (25.2) | 6 (18.8) | 98 (25.8) |

| EoE-related ER visit in the 12 months prior to data collection, n (%) | 122 (29.6) | 10 (31.3) | 112 (29.5) |

| Mean number of EoE-related ER visits (SD) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) |

| History of elemental formula diet, n (%) | 31 (7.9) | 7 (21.9) | 24 (6.6) |

| Time on elemental formula diet (SD), weeks | 67.2 (109.3) | 75.5 (125.5) | 65.7 (107.3) |

| History of elimination diet, n (%) | 80 (19.9) | 10 (31.3) | 70 (18.9) |

Time since diagnosis is calculated from known date of diagnosis to index date (the date the patient consulted with the physician).

Note: Missing responses from patients are excluded.

BMI, body mass index; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; ER, emergency room; EU, European.

Baseline patient demographics and clinical characteristics (physician reported)

| . | All (N = 412) . | 12–17 years (n = 32) . | ≥18 years (n = 380) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), years | 37.0 (15.3) | 15.5 (1.7) | 38.8 (14.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 275 (66.7) | 21 (65.6) | 254 (66.8) |

| Mean BMI (SD), kg/m 2 | 24.5 (3.6) | 21.8 (3.2) | 24.8 (3.6) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | n = 408 | n = 32 | n = 376 |

| White | 353 (86.5) | 22 (68.8) | 331 (88.0) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 19 (4.7) | 4 (12.5) | 15 (4.0) |

| African American (US) | 10 (2.5) | 1 (3.1) | 9 (2.4) |

| Afro-Caribbean (EU) | 7 (1.7) | 1 (3.1) | 6 (1.6) |

| Asian-Indian subcontinent | 6 (1.5) | 3 (9.4) | 3 (0.8) |

| Asian-other | 5 (1.2) | 1 (3.1) | 4 (1.1) |

| Mixed race | 4 (1.0) | 0 | 4 (1.1) |

| Middle Eastern | 3 (0.7) | 0 | 3 (0.8) |

| Other | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Mean time since diagnosis (SD), months a | 32.1 (43.2) | 35.1 (31.2) | 31.8 (44.1) |

| Mean time since current pharmaceutical treatment initiation (SD), months | 17.3 (21.3) | 23.8 (22.6) | 16.7 (21.2) |

| History of dilation due to EoE, n (%) | 104 (25.2) | 6 (18.8) | 98 (25.8) |

| EoE-related ER visit in the 12 months prior to data collection, n (%) | 122 (29.6) | 10 (31.3) | 112 (29.5) |

| Mean number of EoE-related ER visits (SD) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) |

| History of elemental formula diet, n (%) | 31 (7.9) | 7 (21.9) | 24 (6.6) |

| Time on elemental formula diet (SD), weeks | 67.2 (109.3) | 75.5 (125.5) | 65.7 (107.3) |

| History of elimination diet, n (%) | 80 (19.9) | 10 (31.3) | 70 (18.9) |

| . | All (N = 412) . | 12–17 years (n = 32) . | ≥18 years (n = 380) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), years | 37.0 (15.3) | 15.5 (1.7) | 38.8 (14.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 275 (66.7) | 21 (65.6) | 254 (66.8) |

| Mean BMI (SD), kg/m 2 | 24.5 (3.6) | 21.8 (3.2) | 24.8 (3.6) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | n = 408 | n = 32 | n = 376 |

| White | 353 (86.5) | 22 (68.8) | 331 (88.0) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 19 (4.7) | 4 (12.5) | 15 (4.0) |

| African American (US) | 10 (2.5) | 1 (3.1) | 9 (2.4) |

| Afro-Caribbean (EU) | 7 (1.7) | 1 (3.1) | 6 (1.6) |

| Asian-Indian subcontinent | 6 (1.5) | 3 (9.4) | 3 (0.8) |

| Asian-other | 5 (1.2) | 1 (3.1) | 4 (1.1) |

| Mixed race | 4 (1.0) | 0 | 4 (1.1) |

| Middle Eastern | 3 (0.7) | 0 | 3 (0.8) |

| Other | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Mean time since diagnosis (SD), months a | 32.1 (43.2) | 35.1 (31.2) | 31.8 (44.1) |

| Mean time since current pharmaceutical treatment initiation (SD), months | 17.3 (21.3) | 23.8 (22.6) | 16.7 (21.2) |

| History of dilation due to EoE, n (%) | 104 (25.2) | 6 (18.8) | 98 (25.8) |

| EoE-related ER visit in the 12 months prior to data collection, n (%) | 122 (29.6) | 10 (31.3) | 112 (29.5) |

| Mean number of EoE-related ER visits (SD) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) |

| History of elemental formula diet, n (%) | 31 (7.9) | 7 (21.9) | 24 (6.6) |

| Time on elemental formula diet (SD), weeks | 67.2 (109.3) | 75.5 (125.5) | 65.7 (107.3) |

| History of elimination diet, n (%) | 80 (19.9) | 10 (31.3) | 70 (18.9) |

Time since diagnosis is calculated from known date of diagnosis to index date (the date the patient consulted with the physician).

Note: Missing responses from patients are excluded.

BMI, body mass index; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; ER, emergency room; EU, European.

Current therapy and HCRU

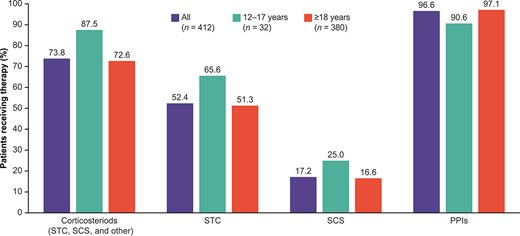

Overall, 7.9% of patients had previously followed an elemental formula (liquid meal replacement) diet, but not an elimination diet (12–17 years: 21.9%; ≥18 years: 6.6%) and 19.9% had previously followed an elimination diet, but not an elemental formula diet (12–17 years: 31.3%; ≥18 years: 18.9%); while 16.7% had previously followed both diets (12–17 years: 34.4%; ≥18 years: 15.3%). Mean (SD) time since current treatment initiation was 17.3 (21.3) months overall (12–17 years: 23.8 [22.6] months; ≥18 years: 16.7 [21.2] months) (Table 1). At the time of the study, 96.6% of patients were receiving PPIs (12–17 years: 90.6%; ≥18 years: 97.1%) (Fig. 1) and 73.8% were receiving swallowed topical/systemic corticosteroids (12–17 years: 87.5%; ≥18 years: 72.6%), mostly budesonide (78.6% of patients treated with corticosteroids; [12–17 years: 85.7%; ≥18 years: 77.9%]). Approximately half (52.4%) of the overall patients received a swallowed topical corticosteroid (12–17 years: 65.6%; ≥18 years: 51.3%) and 17.2% received a systemic corticosteroid (12–17 years: 25.0%; ≥18 years: 16.6%). Esophageal dilations were performed in 25.2% (12–17 years: 18.8%; ≥18 years: 25.8%) of patients. EoE-related emergency room (ER) visits in the 12 months prior to data collection were reported for 29.6% (12–17 years: 31.3%; ≥18 years: 29.5%) of patients. The mean (SD) number of ER visits due to EoE over the last 12 months among patients with at least one visit was 1.3 (0.7) (12–17 years: 1.5 [0.7]; ≥18 years: 1.3 [0.7]).

Pharmaceutical treatments currently received by patients with EoE aged ≥12 years for treatment of EoE as reported by physicians. Note: Corticosteroids include budesonide, ciclesonide, betamethasone, prednisone, other (unspecified); PPIs include omeprazole, lansoprazole, dexlansoprazole, esomeprazole, other (unspecified); biologics include dupilumab, mepolizumab, reslizumab, omalizumab, other (unspecified); antihistamines include ranitidine, cetirizine, loratadine, other (unspecified). Proportions are not mutually exclusive. At the time this study was conducted no biologic was approved for the treatment of EoE. EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; SCS, systemic corticosteroids; STC, swallowed topical corticosteroids.

Comorbidity burden

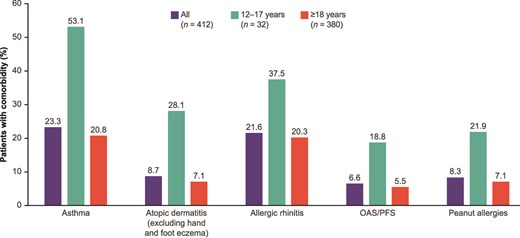

Physician-reported type 2 inflammatory comorbidities were present in 47.1% of the overall sample of 412 patients. The type 2 inflammatory comorbidities with the highest prevalence were asthma (23.3%) and allergic rhinitis (21.6%; Fig. 2). Type 2 comorbidities appeared to be more frequently reported in patients aged 12–17 years than in patients aged ≥18 years (12–17 years: 78.1%; ≥18 years: 44.5%). Asthma, AD, and allergic rhinitis were reported in approximately half (53.1%) and one-third (28.1% and 37.5%) of patients aged 12–17 years, respectively. In patients aged ≥18 years, the rates of type 2 comorbidities ranged from 2.9% (hand and foot eczema) to 20.8% (asthma).

Physician-reported comorbidity burden among patients with EoE aged ≥12 years by patient age. EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; OAS, oral allergy syndrome; PFS, pollen food allergy syndrome.

Symptom burden

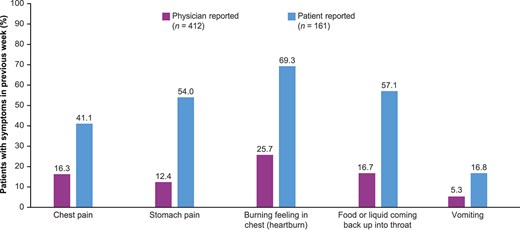

All enrolled patients had symptoms related to dysphagia, food impaction, or choking as part of the inclusion criteria. Beyond these, the most common symptom as reported by patients or caregivers was heartburn (69.3%), followed by food or liquid coming back up into the throat (57.1%), stomach pain (54.0%), chest pain (41.1%), and vomiting (16.8%; Fig. 3). Physicians were also asked to report on the occurrence of these symptoms in their patients (Supplementary Table S2). When compared with physician-reported symptoms, patients reported a higher symptom burden for chest pain, stomach pain, heartburn, food or liquid coming back up into the throat, and vomiting (Fig. 3).

EoE symptom burden other than dysphagia as reported by physicians and patients. a,b,c,dMissing responses from patients are excluded. bFor 14 patients, the caregiver reported on their behalf. cPatients were asked to report the symptoms experienced in the 7 days prior, and physicians were asked to report the symptoms the patients were currently experiencing.

QOL burden

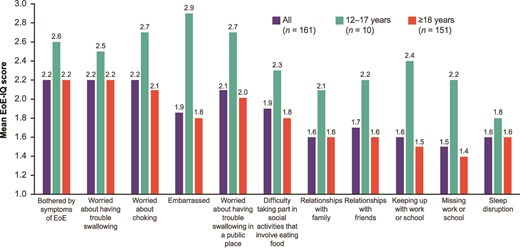

Impairment in QOL was also reported by patients and their caregivers. The aspects associated with the highest negative impact (as measured by mean EoE-IQ scores) in the overall cohort (n = 161) were ‘Bothered by symptoms of EoE’ (2.2), ‘Worried about having trouble swallowing’ (2.2), and ‘Worried about choking’ (2.2; Fig. 4). Slightly higher scores across all aspects of QOL were observed for participants aged 12–17 years compared with participants aged ≥18 years; the greatest QOL impact scores in patients aged 12–17 years were associated with feeling ‘Embarrassed’ (2.9), ‘Worried about choking’ (2.7), and ‘Worried about having trouble swallowing in a public place’ (2.7). In patients aged ≥18 years, the highest QOL impact scores were associated with ‘Bothered by symptoms of EoE’ (2.2), ‘Worried about having trouble swallowing’ (2.2), and ‘Worried about choking’ (2.1).

EoE-IQ impact of EoE symptoms in previous 7 days. a,bMissing responses excluded. bScore range 1–5, where the score of 1 indicates ‘no impact,’ and 5 indicates ‘extremely high impact.’ EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; EoE-IQ, EoE Impact Questionnaire.

DISCUSSION

In this real-world analysis of patient records from the Adelphi Real World EoE Disease Specific Programme™, the disease burden was substantial in EoE patients with a history of PPI use and symptomatic disease at study enrollment. Use of swallowed topical and systemic corticosteroids was shown to be high, with three-quarters of patients currently receiving a corticosteroid for the treatment of their EoE. The highest rates of use were observed in patients in the 12–17 years age group. Approximately 20% of patients were treated with systemic corticosteroids, despite a lack of evidence supporting their use in patients with EoE. Systemic steroids have not been shown to be superior to swallowed corticosteroids in terms of clinical outcomes and histological remission and are associated with a range of side effects.20–22

Patients in this analysis received numerous treatments for EoE, including PPIs and swallowed topical and systemic corticosteroids, yet one-quarter of patients had a history of dilation, and nearly one-third had an EoE-related ER visit in the past 12 months. Furthermore, despite clinical management with these agents, a high number of patients still reported EoE symptoms beyond dysphagia, including heartburn and regurgitation of food and/or liquid. These findings suggest that many patients with EoE still experience a considerably high disease burden despite treatment with PPIs and steroids, and additional therapies may be considered in these patients.

It should be noted that our data show a discrepancy between patient-reported and physician-reported symptoms. Almost 40% of patients with physician-reported data also provided self-reported symptom data, with patients reporting a considerably higher number of symptoms compared with physicians. This might be an indicator that physicians underestimate the symptoms experienced by patients or that patients may not fully disclose their symptoms to their treating physicians. A more comprehensive assessment of symptoms in EoE patients, including probing questions, may be necessary to fully understand the impact of disease on the patient and better tailor treatments.

There was a high prevalence of type 2 comorbidities among EoE patients, with almost half of patients having an additional disease associated with type 2 inflammation, which confirms previous evidence showing that most patients with EoE have concurrent type 2 comorbidities.17 In the overall population, the most frequently reported type 2 comorbidities were asthma and allergic rhinitis. Type 2 comorbidities were more prevalent in adolescent vs adult patients with EoE.

A potential reason for the high symptom and comorbidity burden observed in this study is that treatments might have been introduced too late in the disease course (i.e. after deposition of subepithelial fibrous tissue) and/or that these treatments do not treat the underlying inflammation associated with EoE. A recent retrospective study of patients with EoE in Switzerland showed that the length of diagnostic delay is directly correlated with an increased risk for stricture formation.3 Lastly, a further potential reason for the observed symptom and QOL burden might be that adherence to the treatments was poor, with non-adherence recognized as a treatment barrier in patients with EoE.23 However, assessment of treatment adherence was outside the scope of this study.

Despite current clinical management, patient QOL was shown to be impaired by EoE, further highlighting the unmet need for treatments that provide adequate symptom control and alleviate the negative QOL impact of the symptoms. Patients primarily reported feeling embarrassed and anxious about their dysphagia, particularly in social settings and during activities that involve eating food. This is in line with previous studies assessing the QOL burden in patients with EoE, which reported high levels of anxiety, particularly in relation to all aspects around swallowing.4,24 Patients also reported negative impacts on their relationships with family and friends, consistent with observations from a previous study in which the impact on psychosocial function and impact on the family were evaluated.25

Adolescent patients generally reported higher comorbidity burden than adults, as well as greater QOL impairment and more frequent use of corticosteroids. Potentially, these patients may have had more advanced disease or a higher perceived burden of disease than patients aged ≥18 years. These findings may suggest that the burden of EoE is greater in adolescents than in adults, but further studies would be required to confirm this. However, it should be noted that QOL burden for patients aged 12–17 years was reported by their caregiver, which might have impacted the results. Patients across both age groups reported a range of symptoms beyond dysphagia, including heartburn, chest pain, stomach pain, food or liquid coming back up into the throat, and vomiting.

Limitations

A potential limitation of this study is the small sample size of the adolescent subgroup of patients (aged 12–17 years), which might represent an underenrollment of this patient population. In addition, a general limitation of patient- or caregiver-reported data is recall bias, which represents a systematic error due to patients or caregivers not accurately remembering an experience. However, this may have been mitigated by the 7-day recall period used in this study, a recall period that has previously been deemed appropriate for EoE.26 Caregivers may also have difficulty in accurately recognizing all symptoms or impacts of EoE in their children, and this should be considered when interpreting the results in adolescent patients. A further limitation of this study is its cross-sectional, noninterventional nature, which does not permit estimation of treatment effects; in addition, the survey approach did not capture details on treatment administration or adherence. Additionally, as the focus of this study was to assess the current burden of EoE in symptomatic patients, our inclusion criteria did not include patients who were asymptomatic at time of survey, nor did we assess improvement in symptoms or remission and how these may relate to disease burden. Nevertheless, the symptom and impact burden captured in this study was substantial. It should also be noted that this analysis was conducted prior to the US approval of dupilumab for use in adults/adolescents in 2022 and in children in 2024 and of budesonide oral suspension in 2024; therefore, observed treatment patterns may not reflect current practice.11,27 Data collection was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and using a convenience sample; as clinical practice was heavily impacted during this time, the study population might have differed to that which may have otherwise been expected. Last, because this study collected data from a range of different countries, the patient population may not be representative of individual countries.

CONCLUSIONS

In this cross-sectional, real-world study, patients with EoE (who received PPI treatment and remained symptomatic) frequently received corticosteroids and other EoE treatments. Despite clinical management with nonbiologic therapies, patients experienced substantial symptom and comorbidity burden as well as impaired QOL, suggesting that their disease was insufficiently controlled and that treatments that target the underlying mechanisms of disease might be more appropriate. New therapies aimed at preventing the progressive damage (i.e. fibrostenosis) associated with EoE provide more treatment options for patients with poorly controlled disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This analysis was sponsored by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Sanofi. Medical writing assistance was provided by Martin Bell and Vanessa Gross of Curo (a division of Envision Pharma Group) and was funded by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Sanofi.

Specific author contributions: Alain M. Schoepfer, Stevie Olsen, James Siddall, Eilish McCann, Siddhesh Kamat, Kinga Borsos, Angela Khodzhayev, Amr Radwan, Tiffany Pela, Juby Jacob-Nara, Sarette T. Tilton, Ryan B. Thomas: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision. Stevie Olsen, James Siddall: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation. Eilish McCann, Siddhesh Kamat, Kinga Borsos, Angela Khodzhayev, Amr Radwan, Tiffany Pela, Juby Jacob-Nara, Sarette T. Tilton, Ryan B. Thomas: Funding acquisition. Ryan B. Thomas: Project administration.

Conflicts of interest: Eilish McCann, Siddhesh Kamat, Angela Khodzhayev, Amr Radwan, and Ryan B. Thomas are employees and stockholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Sarette T. Tilton, Tiffany Pela, and Juby Jacob-Nara are employees and stockholders of Sanofi. At the time of the research Kinga Borsos was also employee and stockholder of Sanofi. Stevie Olsen and James Siddall are employees of Adelphi Real World, which received funding from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi for this analysis. Alain M. Schoepfer is a consultant for Dr Falk Pharma GmbH, Ellodi Pharmaceuticals Inc, Celgene-Receptos-BMS, GlaxoSmithKline, and Regeneron-Sanofi-Genzyme.

References

Dupixent® (dupilumab) approved by European Commission as the first and only targeted medicine indicated for eosinophilic esophagitis.