-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Muhammed A Memon, Emma Osland, Rossita M Yunus, Khorshed Alam, Zahirul Hoque, Shahjahan Khan, Gastroesophageal reflux disease following laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic roux-en-Y gastric bypass: meta-analysis and systematic review of 5-year data, Diseases of the Esophagus, Volume 37, Issue 3, March 2024, doad063, https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/doad063

Close - Share Icon Share

Summary

To compare 5-year gastroesophageal reflux outcomes following Laparoscopic Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy (LVSG) and Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) based on high quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs). We conducted a sub-analysis of our systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs of primary LVSG and LRYGB procedures in adults for 5-year post-operative complications (PROSPERO CRD42018112054). Electronic databases were searched from January 2015 to July 2021 for publications meeting inclusion criteria. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman random effects model was utilized to estimate weighted mean differences where meta-analysis was possible. Bias and certainty of evidence was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 2 and GRADE. Four RCTs were included (LVSG n = 266, LRYGB n = 259). An increase in adverse GERD outcomes were observed at 5 years postoperatively in LVSG compared to LRYGB in all outcomes considered: Overall worsened GERD, including the development de novo GERD, occurred more commonly following LVSG compared to LRYGB (OR 5.34, 95% CI 1.67 to 17.05; p = 0.02; I2 = 0%; (Moderate level of certainty); Reoperations to treat severe GERD (OR 7.22, 95% CI 0.82 to 63.63; p = 0.06; I2 = 0%; High level of certainty) and non-surgical management for worsened GERD (OR 3.42, 95% CI 1.16 to 10.05; p = 0.04; I2 = 0%; Low level of certainty) was more common in LVSG patients. LVSG is associated with the development and worsening of GERD symptoms compared to LRYGB at 5 years postoperatively leading to either introduction/increased pharmacological requirement or further surgical treatment. Appropriate patient/surgical selection is critical to minimize these postoperative risks.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity has been linked to the development and exacerbation of a variety of chronic health conditions including gastresophageal reflux disease (GERD). GERD is the condition in which the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. GERD is objectively defined by the presence of characteristic mucosal injury seen at endoscopy and/or abnormal esophageal acid exposure demonstrated on a 24-hour reflux monitoring study.1 Symptoms most commonly present as heartburn and acid regurgitation. Atypical symptoms including chest pain, nausea, belching, dyspepsia and epigastric fullness or pain, and extraesophageal symptoms such as vocal hoarseness, coughing, wheezing, asthma, and dental erosions are also recognized.1 Complications resulting from GERD include erosive esophagitis (EE), peptic strictures (PS), Barrett’s esophagus (BE), esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), and lung disease.1

A strong correlation exists between obesity (defined by body mass index [BMI] >30 kg/m2) and GERD symptoms, esophageal acid exposure, and GERD complications such as EE, BE, and EAC. This has been confirmed in population-based studies in the last decade.2 The relationship between GERD and obesity is thought to be multifactorial, however it is generally attributed to an increase in abdominal and intragastric pressure, the presence of hiatus hernias, and increased gradient of abdominal to thoracic pressures (gastroesophageal pressure gradient), and lower esophageal sphincter (LES) abnormalities, although other considerations such as increase estrogen levels may also contribute.3

Bariatric surgery is increasingly promoted as an effective means to improve individual obesity-related health outcomes,4 with the laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy (LVSG) and the laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) currently being the most commonly performed bariatric procedures.4 While both procedures are considered to be effective at producing long-term weight loss and comorbid disease improvement, an increasing number of reports suggest that worsened GERD outcomes may be associated with LVSG,5 and conditional recommendations against this procedure being used in those with pre-existing severe GERD or EE are emerging.5 The present work therefore focuses specifically on the comparative 5-year GERD outcomes following LVSG versus LRYGB based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to determine the overall difference in the GERD symptoms between these two bariatric procedure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inclusion and exclusion criteria and search strategies

As the present work is a continuation of our previous systematic review and meta-analyses on the topic, the inclusion and exclusion criteria remained consistent with our previous works6—in brief, only RCTs describing clinical outcomes of LRYGB with LVSG performed in adult patients were eligible for inclusion. The search strategies previously described were re-run with the addition of ‘five years’ and ‘long-term’, published between January 2015 to July 2021 to identify any new RCTs published meeting inclusion criteria (Supplementary Material 1). ‘GERD’ or other variations described reflux disease were not specifically included as search terms in keeping with the broad search strategy adopted.

Data collation

Literature searches were undertaken independently by two authors (EO and MAM). Papers eligible for inclusion were determined by consensus. Data extraction was conducted by one author (EO) in accordance with predefined complication outcomes that included GERD (Supplementary Data). This was reviewed (by MAM) for agreement. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 2 was applied to included studies,7 and the strength of evidence of the outcomes were assessed using GRADE8 with the assistance of GRADEPro software.9 Any disagreements that developed regarding these independent assessments (EO, MAM), were discussed until consensus was reached. The review was registered prospectively with PROSPERO (CRD42018112054), and has been reported in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020).10

Statistical analysis

All included studies underwent qualitative analysis, and meta-analysis was undertaken for variables where sufficient data was available. Odds ratio (OR) was used to measure the association between binary outcome variables. Weighted mean differences (WMD) were calculated using the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman (HKSJ) estimation method for random effects model (REM).11 Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochrane’s Q statistic and I2 index. Point estimates of the population effect sizes and forest plots of 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were produced using metafor package in R.12 Funnel plots were produced to assess the presence of publication bias. Significance test of the population effect size was conducted using t-statistic. A P-value of ˂0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

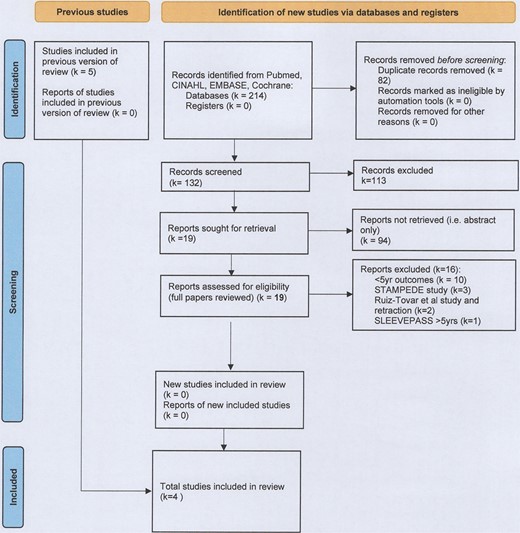

Six studies meeting inclusion criteria were identified, however only four studies were included in the final analysis (LVSG n = 266, LRYGB n = 259)13–16 (Fig. 1, Table 1). All included studies reported long-term follow-up data from studies included in our original systematic review and meta-analysis on this topic.13–16

| Study (name)/ Year of publication/ Location . | Study design (sites)/ Intended Duration (year of study commencement)/ Trial identifier . | Number in follow-up at 5 years (% of baseline in follow up at 5 years) . | Analysis (Analysis approach—equivalence margin if applicable) . | Inclusions . | Exclusions . | GERD outcomes described . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVSG . | LRYGB . | BMI (kg/m2) . | Age (years) . | Other . | |||||

| Zhang et al./ 2014/ China | Single center prospective RCT/ 5 years (2007)/ No trial number provided | 26 (87.5) | 28 (81.2) | ITT (superiority) | >32 to <50 | 16–60 | Acceptance of randomization | Chronic or psychiatric illness, substance abuse, previously GI surgery | Comorbidity Not reported as comorbidity Complication GERD-related complications reported |

| Ignat et al./ 2017/ France | Single center prospective RCT/non-inferiority trial; 10 years (2009)/ NCT02475590 | 32 (45–13) (71.1) | 41 (55–14) (75.4) | ITT (superiority) | >40 and < 60 | 18–60 | No contraindication for surgery or anesthesia, able and willing to provide consent. | Psychiatric illness, pregnancy, immune- suppression, coagulopathy, anemia, malabsorptive disease, MI, angina or HF, previous GI surgery, HH >2 cm | Comorbidity Not reported as comorbidity Complication Hospital readmission and/or surgical intervention for GERD-related complications |

| Salminen et al. (SLEEVEPASS)/ 2018/ Finland | Multicentre prospective RCT (3 sites)/equivalence trial/ 15 years (2008) NCT00793143 | 98 (80.1) | 95 (81.1) | ITT for procedure, but missing data excluded from analysis (PP for GERD outcomes) (Equivalence—±9% EWL) | ≥40 or ≥35 with comorbidities | 18–60 | Previously failed conservative management | BMI >60, psychiatric illness, eating disorder, alcohol or substance abuse, active gastric ulcer disease, severe GERD with large HH, previous bariatric surgery | Comorbidity Not reported as comorbidity Complication Major (Clavien-Dindo IIIb or above) and minor (Clavien-Dindo IIIa or below) GERD-related complications |

| Peterli et al. (SM-BOSS)/ 2018/ Switzerland | Multicentre prospective RCT (4 sites)/ 5 years (2006)/ NCT00356213 | 101 (90.1) | 104 (92.8) | ITT for procedure with multiple imputation technique for missing data (Equivalence—±10% EBMIL) | >40 with comorbidities | 18–65 | 2 years unsuccessful conservative management | Major abdominal surgery, IBD, previous bariatric surgery, severe GERD despite medication, large HH, expected dense small bowel adhesions | Comorbidity Remission, improved, unchanged or worsened from baseline or se novo development; as defined by physician at each review. Complication Reoperation or intervention for GERD-related complications |

| Study (name)/ Year of publication/ Location . | Study design (sites)/ Intended Duration (year of study commencement)/ Trial identifier . | Number in follow-up at 5 years (% of baseline in follow up at 5 years) . | Analysis (Analysis approach—equivalence margin if applicable) . | Inclusions . | Exclusions . | GERD outcomes described . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVSG . | LRYGB . | BMI (kg/m2) . | Age (years) . | Other . | |||||

| Zhang et al./ 2014/ China | Single center prospective RCT/ 5 years (2007)/ No trial number provided | 26 (87.5) | 28 (81.2) | ITT (superiority) | >32 to <50 | 16–60 | Acceptance of randomization | Chronic or psychiatric illness, substance abuse, previously GI surgery | Comorbidity Not reported as comorbidity Complication GERD-related complications reported |

| Ignat et al./ 2017/ France | Single center prospective RCT/non-inferiority trial; 10 years (2009)/ NCT02475590 | 32 (45–13) (71.1) | 41 (55–14) (75.4) | ITT (superiority) | >40 and < 60 | 18–60 | No contraindication for surgery or anesthesia, able and willing to provide consent. | Psychiatric illness, pregnancy, immune- suppression, coagulopathy, anemia, malabsorptive disease, MI, angina or HF, previous GI surgery, HH >2 cm | Comorbidity Not reported as comorbidity Complication Hospital readmission and/or surgical intervention for GERD-related complications |

| Salminen et al. (SLEEVEPASS)/ 2018/ Finland | Multicentre prospective RCT (3 sites)/equivalence trial/ 15 years (2008) NCT00793143 | 98 (80.1) | 95 (81.1) | ITT for procedure, but missing data excluded from analysis (PP for GERD outcomes) (Equivalence—±9% EWL) | ≥40 or ≥35 with comorbidities | 18–60 | Previously failed conservative management | BMI >60, psychiatric illness, eating disorder, alcohol or substance abuse, active gastric ulcer disease, severe GERD with large HH, previous bariatric surgery | Comorbidity Not reported as comorbidity Complication Major (Clavien-Dindo IIIb or above) and minor (Clavien-Dindo IIIa or below) GERD-related complications |

| Peterli et al. (SM-BOSS)/ 2018/ Switzerland | Multicentre prospective RCT (4 sites)/ 5 years (2006)/ NCT00356213 | 101 (90.1) | 104 (92.8) | ITT for procedure with multiple imputation technique for missing data (Equivalence—±10% EBMIL) | >40 with comorbidities | 18–65 | 2 years unsuccessful conservative management | Major abdominal surgery, IBD, previous bariatric surgery, severe GERD despite medication, large HH, expected dense small bowel adhesions | Comorbidity Remission, improved, unchanged or worsened from baseline or se novo development; as defined by physician at each review. Complication Reoperation or intervention for GERD-related complications |

BMI, Body Mass Index; EBMIL, Excess Body Mass Index Lost; EWL, Excess Weight Lost; GERD, Gastroesophageal reflux disease; GI, Gastrointestinal; HbA1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; HF, heart failure; HH, hiatus hernia; HTN, hypertension; ITT, Intention to Treat; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; IBD, Inflammatory Bowel Disease; MI, Myocardial infarction; NCT, National Clinical Trial (unique identifier provided via ClinicalTrials.gov); OSA, Obstructive Sleep Apnoea; PP, Per Protocol; RCT, Randomized Controlled Trial; T2DM, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; TG, triglycerides.

| Study (name)/ Year of publication/ Location . | Study design (sites)/ Intended Duration (year of study commencement)/ Trial identifier . | Number in follow-up at 5 years (% of baseline in follow up at 5 years) . | Analysis (Analysis approach—equivalence margin if applicable) . | Inclusions . | Exclusions . | GERD outcomes described . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVSG . | LRYGB . | BMI (kg/m2) . | Age (years) . | Other . | |||||

| Zhang et al./ 2014/ China | Single center prospective RCT/ 5 years (2007)/ No trial number provided | 26 (87.5) | 28 (81.2) | ITT (superiority) | >32 to <50 | 16–60 | Acceptance of randomization | Chronic or psychiatric illness, substance abuse, previously GI surgery | Comorbidity Not reported as comorbidity Complication GERD-related complications reported |

| Ignat et al./ 2017/ France | Single center prospective RCT/non-inferiority trial; 10 years (2009)/ NCT02475590 | 32 (45–13) (71.1) | 41 (55–14) (75.4) | ITT (superiority) | >40 and < 60 | 18–60 | No contraindication for surgery or anesthesia, able and willing to provide consent. | Psychiatric illness, pregnancy, immune- suppression, coagulopathy, anemia, malabsorptive disease, MI, angina or HF, previous GI surgery, HH >2 cm | Comorbidity Not reported as comorbidity Complication Hospital readmission and/or surgical intervention for GERD-related complications |

| Salminen et al. (SLEEVEPASS)/ 2018/ Finland | Multicentre prospective RCT (3 sites)/equivalence trial/ 15 years (2008) NCT00793143 | 98 (80.1) | 95 (81.1) | ITT for procedure, but missing data excluded from analysis (PP for GERD outcomes) (Equivalence—±9% EWL) | ≥40 or ≥35 with comorbidities | 18–60 | Previously failed conservative management | BMI >60, psychiatric illness, eating disorder, alcohol or substance abuse, active gastric ulcer disease, severe GERD with large HH, previous bariatric surgery | Comorbidity Not reported as comorbidity Complication Major (Clavien-Dindo IIIb or above) and minor (Clavien-Dindo IIIa or below) GERD-related complications |

| Peterli et al. (SM-BOSS)/ 2018/ Switzerland | Multicentre prospective RCT (4 sites)/ 5 years (2006)/ NCT00356213 | 101 (90.1) | 104 (92.8) | ITT for procedure with multiple imputation technique for missing data (Equivalence—±10% EBMIL) | >40 with comorbidities | 18–65 | 2 years unsuccessful conservative management | Major abdominal surgery, IBD, previous bariatric surgery, severe GERD despite medication, large HH, expected dense small bowel adhesions | Comorbidity Remission, improved, unchanged or worsened from baseline or se novo development; as defined by physician at each review. Complication Reoperation or intervention for GERD-related complications |

| Study (name)/ Year of publication/ Location . | Study design (sites)/ Intended Duration (year of study commencement)/ Trial identifier . | Number in follow-up at 5 years (% of baseline in follow up at 5 years) . | Analysis (Analysis approach—equivalence margin if applicable) . | Inclusions . | Exclusions . | GERD outcomes described . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVSG . | LRYGB . | BMI (kg/m2) . | Age (years) . | Other . | |||||

| Zhang et al./ 2014/ China | Single center prospective RCT/ 5 years (2007)/ No trial number provided | 26 (87.5) | 28 (81.2) | ITT (superiority) | >32 to <50 | 16–60 | Acceptance of randomization | Chronic or psychiatric illness, substance abuse, previously GI surgery | Comorbidity Not reported as comorbidity Complication GERD-related complications reported |

| Ignat et al./ 2017/ France | Single center prospective RCT/non-inferiority trial; 10 years (2009)/ NCT02475590 | 32 (45–13) (71.1) | 41 (55–14) (75.4) | ITT (superiority) | >40 and < 60 | 18–60 | No contraindication for surgery or anesthesia, able and willing to provide consent. | Psychiatric illness, pregnancy, immune- suppression, coagulopathy, anemia, malabsorptive disease, MI, angina or HF, previous GI surgery, HH >2 cm | Comorbidity Not reported as comorbidity Complication Hospital readmission and/or surgical intervention for GERD-related complications |

| Salminen et al. (SLEEVEPASS)/ 2018/ Finland | Multicentre prospective RCT (3 sites)/equivalence trial/ 15 years (2008) NCT00793143 | 98 (80.1) | 95 (81.1) | ITT for procedure, but missing data excluded from analysis (PP for GERD outcomes) (Equivalence—±9% EWL) | ≥40 or ≥35 with comorbidities | 18–60 | Previously failed conservative management | BMI >60, psychiatric illness, eating disorder, alcohol or substance abuse, active gastric ulcer disease, severe GERD with large HH, previous bariatric surgery | Comorbidity Not reported as comorbidity Complication Major (Clavien-Dindo IIIb or above) and minor (Clavien-Dindo IIIa or below) GERD-related complications |

| Peterli et al. (SM-BOSS)/ 2018/ Switzerland | Multicentre prospective RCT (4 sites)/ 5 years (2006)/ NCT00356213 | 101 (90.1) | 104 (92.8) | ITT for procedure with multiple imputation technique for missing data (Equivalence—±10% EBMIL) | >40 with comorbidities | 18–65 | 2 years unsuccessful conservative management | Major abdominal surgery, IBD, previous bariatric surgery, severe GERD despite medication, large HH, expected dense small bowel adhesions | Comorbidity Remission, improved, unchanged or worsened from baseline or se novo development; as defined by physician at each review. Complication Reoperation or intervention for GERD-related complications |

BMI, Body Mass Index; EBMIL, Excess Body Mass Index Lost; EWL, Excess Weight Lost; GERD, Gastroesophageal reflux disease; GI, Gastrointestinal; HbA1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; HF, heart failure; HH, hiatus hernia; HTN, hypertension; ITT, Intention to Treat; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; IBD, Inflammatory Bowel Disease; MI, Myocardial infarction; NCT, National Clinical Trial (unique identifier provided via ClinicalTrials.gov); OSA, Obstructive Sleep Apnoea; PP, Per Protocol; RCT, Randomized Controlled Trial; T2DM, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; TG, triglycerides.

A report representing 5- to 7-year data from the SLEEVEPASS study was identified and was excluded due to providing data outside of the specified 5-year timeframe.17 An additional study that would have otherwise met inclusion criteria was excluded in view of the retraction of this paper in March 2021 after errors in data transcription had been identified.18 The STAMPEDE study was also excluded as the intensive medical interventions provided alongside surgical interventions were considered to be a key difference from the other included studies, representing a significant confounding factor in a review seeking to ascertain the impact of bariatric surgery on comorbid disease resolution and remission.19

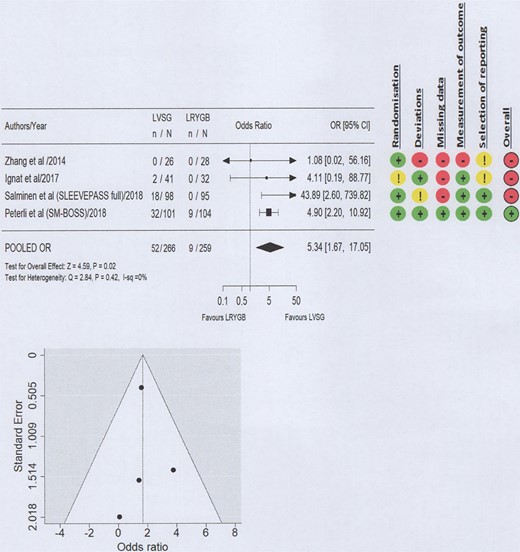

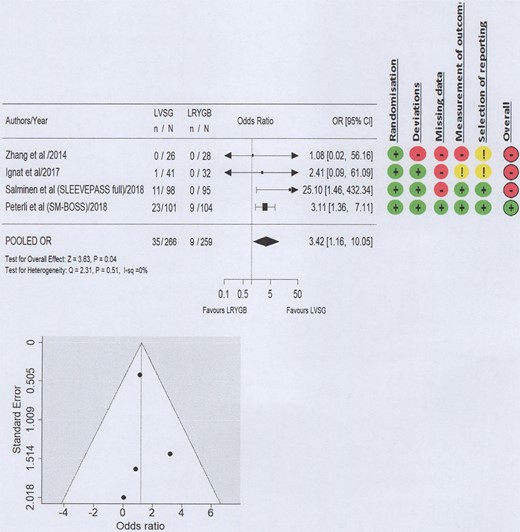

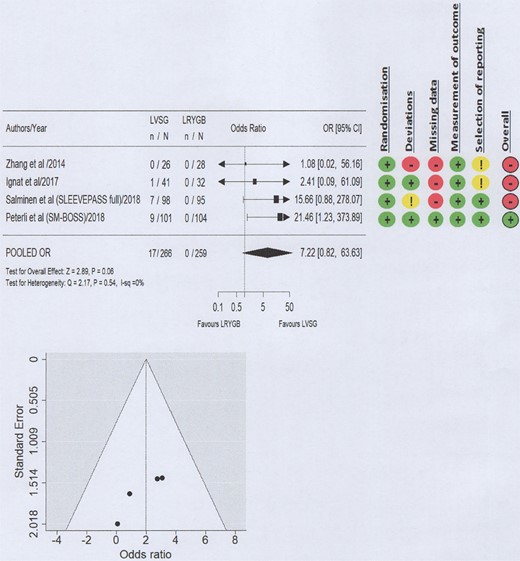

A high level of bias with relation to GERD outcomes was seen in three of the four included studies (Figs 2–4; Supplementary Material 2) and the certainty of evidence ranged from low to high (Table 2). Funnel plots did not suggest the presence of publication bias (Figs 2–4).

Forest plot and Risk of Bias 2 for worsened GERD post-operative outcomes (all treatment modalities).

Forest plot and Risk of Bias 2 for non-surgical management for worsened GERD.

Forest plot and Risk of Bias 2 for reoperations for management of severe GERD.

| Certainty assessment . | No. of patients . | Effect . | Certainty . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies . | Study design . | Risk of bias . | Inconsistency . | Indirectness . | Imprecision . | Other considerations . | LVSG . | LRYGB . | Relative (95% CI) . | Absolute (95% CI) . | |

| Worsening or development of new of GERD symptoms—All management (follow-up: 5 years; assessed with: PPI use, worsened symptoms, surgical revision) | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | not serious | seriousa | seriousb | seriousc | Strong association all plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 52/266 (19.5%) | 9/259 (3.5%) | OR 5.34 (1.67–17.05) | 126 more per 1000 (from 22 more to 346 more) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ Moderate |

| Worsened or development of new GERD symptoms—new or increased Rx requirements (follow-up: 5 years; assessed with: PPI, symptoms) | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | seriousd | seriousa | seriousb | seriousc | Strong association all plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 35/266 (13.2%) | 9/259 (3.5%) | OR 3.42 (1.16–10.05) | 75 more per 1000 (from 5 more to 231 more) | ⊕⊕◯◯ Low |

| Worsened or development of new GERD requiring surgical intervention (follow-up: 5 years; assessed with: LVSG to LRYGB) | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | not serious | not serious | not serious | seriousc | Very strong association | 17/266 (6.4%) | 0/259 (0.0%) | OR 7.22 (0.82–63.63) | 0 fewer per 1000 (from 0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

| Certainty assessment . | No. of patients . | Effect . | Certainty . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies . | Study design . | Risk of bias . | Inconsistency . | Indirectness . | Imprecision . | Other considerations . | LVSG . | LRYGB . | Relative (95% CI) . | Absolute (95% CI) . | |

| Worsening or development of new of GERD symptoms—All management (follow-up: 5 years; assessed with: PPI use, worsened symptoms, surgical revision) | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | not serious | seriousa | seriousb | seriousc | Strong association all plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 52/266 (19.5%) | 9/259 (3.5%) | OR 5.34 (1.67–17.05) | 126 more per 1000 (from 22 more to 346 more) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ Moderate |

| Worsened or development of new GERD symptoms—new or increased Rx requirements (follow-up: 5 years; assessed with: PPI, symptoms) | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | seriousd | seriousa | seriousb | seriousc | Strong association all plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 35/266 (13.2%) | 9/259 (3.5%) | OR 3.42 (1.16–10.05) | 75 more per 1000 (from 5 more to 231 more) | ⊕⊕◯◯ Low |

| Worsened or development of new GERD requiring surgical intervention (follow-up: 5 years; assessed with: LVSG to LRYGB) | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | not serious | not serious | not serious | seriousc | Very strong association | 17/266 (6.4%) | 0/259 (0.0%) | OR 7.22 (0.82–63.63) | 0 fewer per 1000 (from 0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

CI, confidence interval; GERD, Gastroesophageal reflux disease; LRYGB, Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; LVSG, Laparoscopic Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy; OR, odds ratio; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; RCTs, randomized controlled trials.

aSignificant variation in effect sizes in the two largest studies owing to differences in reporting.

bGERD definition and GERD at baseline not reported in 60% of participants.

cLow number of events (<100) does not meet threshold for certainty around precision.

dDifferences in reporting of this outcome may introduce bias and may underestimate real outcome.

| Certainty assessment . | No. of patients . | Effect . | Certainty . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies . | Study design . | Risk of bias . | Inconsistency . | Indirectness . | Imprecision . | Other considerations . | LVSG . | LRYGB . | Relative (95% CI) . | Absolute (95% CI) . | |

| Worsening or development of new of GERD symptoms—All management (follow-up: 5 years; assessed with: PPI use, worsened symptoms, surgical revision) | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | not serious | seriousa | seriousb | seriousc | Strong association all plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 52/266 (19.5%) | 9/259 (3.5%) | OR 5.34 (1.67–17.05) | 126 more per 1000 (from 22 more to 346 more) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ Moderate |

| Worsened or development of new GERD symptoms—new or increased Rx requirements (follow-up: 5 years; assessed with: PPI, symptoms) | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | seriousd | seriousa | seriousb | seriousc | Strong association all plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 35/266 (13.2%) | 9/259 (3.5%) | OR 3.42 (1.16–10.05) | 75 more per 1000 (from 5 more to 231 more) | ⊕⊕◯◯ Low |

| Worsened or development of new GERD requiring surgical intervention (follow-up: 5 years; assessed with: LVSG to LRYGB) | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | not serious | not serious | not serious | seriousc | Very strong association | 17/266 (6.4%) | 0/259 (0.0%) | OR 7.22 (0.82–63.63) | 0 fewer per 1000 (from 0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

| Certainty assessment . | No. of patients . | Effect . | Certainty . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies . | Study design . | Risk of bias . | Inconsistency . | Indirectness . | Imprecision . | Other considerations . | LVSG . | LRYGB . | Relative (95% CI) . | Absolute (95% CI) . | |

| Worsening or development of new of GERD symptoms—All management (follow-up: 5 years; assessed with: PPI use, worsened symptoms, surgical revision) | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | not serious | seriousa | seriousb | seriousc | Strong association all plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 52/266 (19.5%) | 9/259 (3.5%) | OR 5.34 (1.67–17.05) | 126 more per 1000 (from 22 more to 346 more) | ⊕⊕⊕◯ Moderate |

| Worsened or development of new GERD symptoms—new or increased Rx requirements (follow-up: 5 years; assessed with: PPI, symptoms) | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | seriousd | seriousa | seriousb | seriousc | Strong association all plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 35/266 (13.2%) | 9/259 (3.5%) | OR 3.42 (1.16–10.05) | 75 more per 1000 (from 5 more to 231 more) | ⊕⊕◯◯ Low |

| Worsened or development of new GERD requiring surgical intervention (follow-up: 5 years; assessed with: LVSG to LRYGB) | |||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | not serious | not serious | not serious | seriousc | Very strong association | 17/266 (6.4%) | 0/259 (0.0%) | OR 7.22 (0.82–63.63) | 0 fewer per 1000 (from 0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

CI, confidence interval; GERD, Gastroesophageal reflux disease; LRYGB, Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; LVSG, Laparoscopic Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy; OR, odds ratio; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; RCTs, randomized controlled trials.

aSignificant variation in effect sizes in the two largest studies owing to differences in reporting.

bGERD definition and GERD at baseline not reported in 60% of participants.

cLow number of events (<100) does not meet threshold for certainty around precision.

dDifferences in reporting of this outcome may introduce bias and may underestimate real outcome.

Adopted definitions of GERD

The SM-BOSS study defined GERD as being present if the patient was prescribed proton pump inhibitor (PPI) medications and/or was found to have EE on endoscopy and/or was demonstrated to have abnormal manometry14 (personal communication). This was surprising to us as the gold standard for detecting GERD is 24-hour ambulatory pH study. Despite being described ‘GERD as a complication’ in the remaining studies, the definitions or objective diagnostic criteria such as 24-hour pH study, to identify GERD were not described.

GERD as a comorbidity

GERD, defined as an a priori comorbidity, was only reported by the SM-BOSS study.14 A total of 45% of their patient cohort was described as experiencing GERD as a comorbidity at baseline, though it should also be noted that the presence of severe GERD was an exclusion criterion for this study.14 Remission of GERD was statistically significantly higher in the LRYGB group in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses (60.4% vs. 25%, P = 0.0006 and P = 0.002, respectively) at 5 years postoperatively. On the other hand, both worsening and de novo development of GERD were significantly associated with LVSG at 5 years (31.8% vs. 6.3%, P = 0.002 and P = 0.006; 31.6% vs. 10.7%, P = 0.01, respectively).14 No differences between improved and unchanged GERD were shown between intervention groups at 5 years.14

GERD as a complication

GERD and GERD-related complications were described among the late complications reported to 5 years postoperatively in all included studies. Of the patients with worsened GERD reported by SM-BOSS, nine patients (8.4%) required a conversion of LVSG to LRYGB to manage GERD symptoms or complications.14 No patients in the LRYGB group required revisional surgery for GERD.14

SLEEVEPASS reported GERD as a late complication in LVSG at 5 years (minor 9.1%; major 5.8%).15 No patients with LRYGB reported GERD complications at any time point.15 In this study, major and minor complications constituted interventions classified as IIIb or IV or I to IIIa, respectively, using the Clavien-Dindo system20: Therefore, major complications by definition constituted a reoperation, while minor complications included those treated with pharmacological management or endoscopic investigation.15 No patients in the LRYGB reported GERD as a late complication at any of these timepoints.15

Ignat et al. reported that two patients who had received LVSG reported GERD-related issues at 5 years postoperatively: One required a conversion of LVSG to LRYGB due to ‘disabling GERD’, the other required hospitalization for management of GERD.16

Conversely, Zhang et al. did not report any patients with GERD as an adverse late outcome. Though three patients in the LVSG group were reported to have developed GERD, their symptoms spontaneously resolve within the first year postoperatively.13

Worsened GERD post-operative outcomes (all treatment modalities)

GERD outcomes were considered to have worsened in the 5 years following primary bariatric surgery if GERD developed as a new complication (de novo), if there was a new or increased requirement for PPI prescription, or if revisional surgery was required to manage the condition. At 5 years postoperatively, 19.1% (52/262) of the patients who received LVSG compared to 3.4% (9/259) of patients who received LRYGB reported worsened GERD outcomes. Meta-analysis demonstrated that LVSG resulted in a statistically significant increase in worsened GERD symptoms at 5 years postoperatively, requiring either pharmacological or surgical management (i.e. encompassing all interventions), compared to LRYGB (OR 5.34, 95% CI 1.67–17.05; P = 0.02; I2 0%; Moderate level of certainty) (Fig. 2).

Non-surgical management for worsened GERD

When considering the requirement for new or increased pharmaceutical management and other non-surgical management of new or worsened GERD symptoms at 5 years postoperatively, LVSG resulted in statistically significant worsened GERD outcomes compared to LRYGB (OR 3.42, 95% CI 1.16–10.05; P = 0.04; Low level of certainty) (Fig. 3).

Reoperations for management of severe GERD

Reoperations for the management of GERD were reported as necessary to deal with severe post-operative GERD symptoms in three of the four included RCTs13–16: In all cases, these constituted a conversion of LVSG to LRYGB. At 5 years postoperatively, 6.25% (17/266) of the patients remaining in follow-up that received a LVSG as their primary procedure required a surgical revision to manage their severe GERD symptoms. No patient who received LRYGB (0/259) required any surgical intervention for GERD symptoms. Meta-analysis suggested that LVSG resulted in large increase in the need for surgical intervention to manage severe GERD compared to LRYGB at 5 years postoperatively (OR 7.22, 95% CI 0.82–63.63; P = 0.06; High level of certainty) (Fig. 4), although it did not reach the statistical significance threshold.

DISCUSSION

While improvements in GERD symptoms have been reported in 40–60% of patients following LVSG, and up to 80% following LRYGB,5,19 the risk of developing de novo reflux following LVSG varies roughly between 8% and 30%, depending on the length of reported follow-up.21,22 The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs provide further support to findings that LVSG is associated with an increase in adverse GERD outcomes relative to LRYGB, and confirms that in many cases, GERD remains an emerging issue at 5 years postoperatively for those who have undergone LVSG. In particular, there appears to be a strong, though not statistically significant, association between the increased need for reoperation for GERD complications in LVSG compared to LRYGB was found in this analysis to be supported by evidence with a high level of certainty. GERD, therefore, has more significant consequences following LVSG compared to LRYGB, and other studies investigating the impact on quality of life have demonstrated GERD’s negative impact on physical functioning, mental health, and emotional wellbeing and collectively resulting in poorer social interactions.23,24

The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis are supported by other literature investigating the topic. A meta-analysis that did not limit inclusions to RCTs conducted by Gu et al. reported the incidence of de novo GERD to be 9.3% in LVSG (n = 1918) compared to 2.3% in LRYGB (n = 1616).25 Similarly, more patients experienced worsening of GERD symptoms following LVSG compared to LRYGB, resulting in between 1.82% and 8.91% of patients in LVSG group requiring conversion to LRYGB surgery to manage severe GERD.25 Furthermore, the validity of the 5-year outcomes found by this review are substantiated by recent publications reporting 5-to-10-year outcomes from the included SLEEVEPASS study demonstrate ongoing worsened GERD outcomes for patients who had undergone LVSG compared to LRYGB.17,26 EE, increasing PPI intake, reflux symptoms, the development of de novo GERD and higher (equating to worse) GERD-health related quality of life scores were reported to be statistically significantly more common following LVSG relative to LRYGB at 10 years postoperatively.26

By contrast other reviews, including those conducted by Chiu et al., Stenard et al., and Oor et al., report a more balanced mix of positive and negative outcomes between procedures with respect to GERD outcomes (4 vs. 7; 13 vs. 12; and 16 vs. 12 studies showing worsened vs. improved GERD outcomes, respectively).27–29 In the latter study, a non-statistically significant trend toward an increased prevalence of GERD symptoms following LVSG among the pooled studies was concluded.29 In addition to the inclusion of lower methodological quality studies, wide ranging follow-up intervals utilized in these studies introduce avoidable heterogeneity and thereby weaken these studies’ ability to elucidate clinically meaningful conclusions. The present work has avoided these limitations by ensuring the inclusion of homogeneous studies (exclusively RCTs, 5-year follow-up), while adopting the most conservative models of meta-analysis to ensure the statistical significance of the outcomes achieved is not overstated. In short, the present work represents the most robust review on the topic based on the strongest available evidence and methodological approaches to meta-analysis.

Comparing the present results with those of the 5-year weight loss outcomes associated with this study30 indicates that GERD outcomes do not follow the linear relationship with weight loss achieved through bariatric surgery seen with other morbid conditions. Other authors have also observed this phenomenon and in an attempt to explain it, have undertaken objective investigations into the physiological consequences of the anatomical changes induced by LVSG. Recent studies based on high-resolution manometry and 24-hour pH monitoring have been conducted in patients undergoing LVSG pre- and postoperatively, and these shed some light on the potential mechanisms by which post-operative GERD may develop.31 Del Genio et al. conducted a prospective study in 25 consecutive patients, in which esophageal manometry demonstrated unchanged LES function, increased ineffective peristalsis, and incomplete bolus transit at a median of 13 months postoperatively, while impedance pH revealed an increase in both acid exposure of the esophagus and the number of non-acid reflux events in postprandial periods.31 A similar study by Burgerhart et al. additionally included an assessment of the Reflux Disease Questionnaire in their 20 patients preoperatively and at the 3-month post-operative assessments.32 Their results showed that while GERD symptoms did not significantly change after LVSG, other upper gastrointestinal symptoms—particularly belching, epigastric pain, and vomiting increased. The percentage of normal peristaltic contractions remained unchanged, but the LES pressure decreased.32 The authors concluded that after LVSG, patients have significantly higher esophageal acid exposure which most likely is secondary to LES dysfunction. Finally, in a retrospective study of 62 patients preoperatively and at 3 months postoperatively,33 Gemici et al. concluded that the LVSG was found to cause a reduction in LES pressure, and an increase in acid reflux causing an extended relaxation time of the LES (dynamic failure).33

LES abnormalities, as described in these studies involving manometry, have been postulated to explain the increased incidence of GERD following LVSG. Anatomical changes to the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) or LES may occur due to iatrogenic injury of sling fibers at the cardia while dissection around the Angle of His during the LVSG procedure. These sling fibers are important in maintaining the EGJ integrity.34,35 This may result in anatomical failure through a decrease in the overall and/or abdominal LES length, and/or dynamic failure through affecting the LES pressure profile,36 which leads to increased lower transient LES relaxations, resulting in GERD. Furthermore, dynamic LES failure may exaggerate GERD symptoms, particularly in cases of coexisting esophageal motility disorders. The latter has been associated with a higher incidence of GERD (24–43%).37

A number of other possible explanations have been put forward to explain the increased incidence of GERD associated with LVSG. First, the presence of hiatus hernia (HH) is likely to be a contributing factor, with high-resolution manometry demonstrating reduced LES pressure in patients with HH compared to those without (13 vs. 8 mm Hg).38 However, a RCT analyzing 100 patients did not show any benefit of repairing <4 cm HH on GERD symptoms over a 12-month follow-up.38 Large HHs (>4 cm), when repaired, have been shown to resolve pre-existing GERD symptoms in 73% of patients, while avoiding de novo development with this management.39

Second, the shape of the sleeve also impacts on the degree of intraluminal pressure created. The smaller the diameter of the gastric lumen post LVSG, the higher the intraluminal pressure and thus the greater the risk of GERD.40 Additionally, resection of the fundus leads to decreased vasovagal reflux and complete elimination of physiological postprandial gastric relaxation further increasing the gastric intraluminal pressure, thus creating a higher risk of GERD. Other factors which increase the risk of GERD included sleeve stenosis (SS), which occurs due to either a use of very small bougie or poor surgical technique leading to kinking, angulation and/or cicatrization of the sleeve. Werquin et al. described three distinct gastric sleeve shapes based on oral contrast study; (a) tubular pattern, (b) superior pouch, and (c) inferior pouch.41 While all shapes had similar GERD symptoms, the inferior pouch shape was associated with the lowest incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms due to decreased intragastric pressure compared to the other two shapes, and higher antral capacity to distend and accommodate gastric contents.41,42 Therefore, patients with antral preserving technique when the first stapler is placed at least 5 cm proximal to the pylorus have a much accelerated gastric emptying compared to those with antral resecting group when the stapler is applied only 2 cm from the pylorus, therefore GERD is likely to be associated with the later.43,44

Third, SS is associated with not only GERD but also nausea, vomiting, food intolerance and may lead to the development of other complications, such as upper third sleeve fistulae. It typically occurs around the incisura (middle part of the stomach), with a reported incidence of 0.5–4%45,46 and its development is attributed to either the use of very small bougie or poor surgical technique leading to kinking, angulation and or cicatrization of the sleeve. The surgical revision rate for LVSG to LRYGB for SS is reported to be ~30%,47 however, this was not indicated among the reasons for revisional surgery in any of the patients from the included studies.

Finally, the size of bougie used to create the sleeve in LVSG has been implicated with GERD outcomes. While there is intense debate regarding the optimum size of the bougie to enhance long-term weight loss and GERD symptom outcomes, the literature suggests that the smaller the bougie, the greater the risk of developing post-operative GERD, SS, and other gastrointestinal symptoms. Recent studies comparing the use of 32 Fr versus 42 Fr bougies to perform LVSG in 120 patients have demonstrated a positive impact on GERD symptoms with the larger bougie size (80% vs. 60%, respectively).48–50

It is encouraging that many of the probable mechanisms for GERD development post LVSG are to some degree modifiable with a change to surgical practice. It is, therefore, plausible that the currently reported association between worsened GERD outcomes and LVSG may improve as surgical practice evolves alongside the elucidation of underlying mechanisms contributing to GERD’s development. This represents a significant opportunity for further research in this area.

There are a number of limitations that need to be acknowledged with the present work. First, the low number of RCTs eligible for inclusion is anticipated to limit statistical power to demonstrate outcomes or to assess for publication bias with confidence. Notwithstanding, this analysis has reported large effect sizes despite the small number of inclusions, and the findings in the 5-year data are supported by the 5–10 data that has been recently published, suggesting that these results are robust enough to guide clinical practice. Second, the variation in reporting of outcomes (i.e. GERD reported as a complication, comorbidity, or both) between the included studies limited some aspects of the review and the subsequent certainty of the evidence presented. There are, however, very clear and strong messages despite this limitation, particularly with regard to the need for reoperation for GERD complications in LVSG recipients. Similarly, the variation in criteria for diagnosing GERD in the published literature is a weakness within and across studies, with even the well designed and otherwise comprehensively reported RCTs included in the present work rarely providing a clear definition of GERD diagnostic criteria. There could be other unexplained factors which may have contributed to GERD in LVSG such as early learning curve, different types of bougies, shape of the sleeve and how close was the resection performed from the antrum.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs further supports that while both LVSG and LRYGB afford long-term improvement in GERD in some patients, LVSG is associated with higher rate of reoperation for the management of GERD-related symptoms as well as a higher incidence of overall worsened GERD outcomes relative to LRYGB at 5 years postoperatively. These findings should be integrated into clinical practice with respect to procedure selection for bariatric surgical candidates in consideration of their underlying comorbidities and risk factors for adverse post-operative GERD outcomes. It also highlights the need for standardization of GERD diagnostic practices and reporting and identifies potential research opportunities for improving GERD outcomes in LVSG recipients. Lastly, standardization of surgical techniques in terms of bougie size and shape of the sleeve may have a major impact on GERD outcome in the long-term as well.

Author contributions

Muhammed Memon (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Emma Osland (Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Rossita Yunus (Formal analysis, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing), Khorshed Alam (Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Zahirul Hoque (Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing), and Shahjahan Khan (Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing)

Data availability

The data used in this MA and SR is already available in published form from the original RCTs.

Section of the journal: Meta-analysis and Systematic Review.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval statement: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any authors.