-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Anjali Vivek, Andrés R Latorre-Rodríguez, Sumeet K Mittal, Magnetic sphincter augmentation for gastroesophageal reflux in overweight and obese patients, Diseases of the Esophagus, Volume 36, Issue Supplement_1, June 2023, doac104, https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/doac104

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA) is a successful treatment option for chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease; however, there is a paucity of data on the efficacy of MSA in obese and morbidly obese patients. To assess the relationship between obesity and outcomes after MSA, we conducted a literature search using MeSH and free-text terms in MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane and Google Scholar. The included articles reported conflicting results regarding the effect of obesity on outcomes after MSA. Prospective observational studies with larger sample sizes and less statistical bias are necessary to understand the effectiveness of MSA in overweight and obese patients.

Key Learning Points

Magnetic sphincter augmentation is an alternative to traditional laparoscopic antireflux surgery for the definitive management of GERD.

Outcomes of magnetic sphincter augmentation are potentially worse in overweight and obese patients.

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is highly prevalent in the Western world with up to 40% of adults reporting symptoms on a weekly basis. Retrograde flow of gastric contents across an incompetent lower esophageal sphincter (LES) complex leads to classical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. Although early stages of GERD and heartburn (i.e. pyrosis) can be managed with acid suppressive therapy, a therapeutic intervention aimed at restoring LES competence remains the definitive treatment.

The gold standard for definitive surgical intervention for pathological GERD is laparoscopic antireflux surgery (LARS). LARS, especially in the hands of foregut specialists, has been shown to have excellent long-term outcomes, but it continues to have an Achilles’ heel: the inability to vomit and the potential to increase bloating. Although it is not an issue with most patients, it is a cause for concern in a subset of patients.

In 2012, the FDA approved magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA) as a less invasive alternative to fundoplication.1 The MSA Linx® Reflux Management System (Ethicon Johnson & Johnson Surgical Technologies) is a device made of magnetic beads that is placed around the LES to improve the esophageal integrity and prevent the reflux of gastric contents.2 In addition to relieving symptoms of GERD, the MRA procedure preserves the ability to vomit and may be associated with less severe bloating compared with traditional LARS. This primary advantage of MSA is due to the design, which allows the magnetic beads to be pushed apart ‘relaxing the LES’ to allow for retrograde venting of gastric contents without permanent disruption. This ‘relaxing’ is initiated by increased intragastric pressure, which increases with an increase in BMI and truncal obesity.

Initially, indications for MSA included normal esophageal motility, BMI <35 kg/m2, no previous foregut surgery, a non-existent or small hiatal hernia and persistent reflux symptoms despite maximal PPI therapy.3 Since then, these criteria have been expanded to include patients with larger hernias, mild esophageal dysmotility, and Barrett’s esophagus.3 The expanded criteria are prevalent in obese patients, particularly those with abdominal obesity.4 Per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines,5 overweight is defined as a BMI between 25.0 and 30 kg/m2, obese as 30.0 kg/m2 or greater, and morbidly obese as greater than 35 kg/m2.

Although research has been conducted to compare outcomes of MSA to those of fundoplication, it is unclear whether these studies explore outcomes in obese patients.6–10 In the early laparoscopic era, a BMI of >35 kg/m2 (morbid obesity) was considered (and, to an extent, still is) a contraindication for LARS, although several recent studies have shown excellent LARS outcomes in this group, equivalent to those of lower BMI groups. However, there is a paucity of data on the effectiveness of MSA in patients with obesity and morbid obesity. This paper aims to review the available literature regarding MSA outcomes in obese and morbidly obese patients.

METHODS

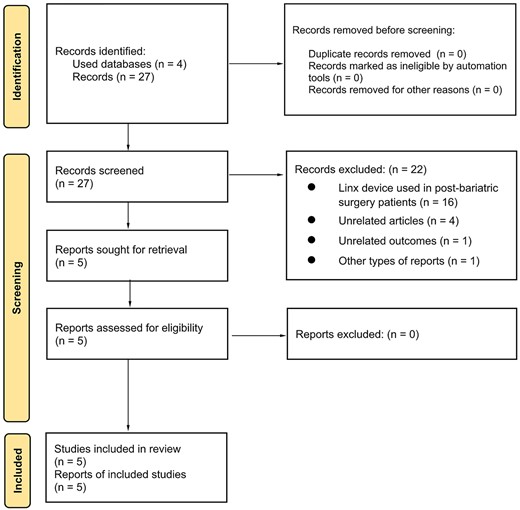

The literature was reviewed using the primary databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane and Google Scholar; no ancillary searches were performed. A mixed-search strategy was implemented using manual and automated searches covering the period from June 2007 to June 2022; the language was limited to English or Spanish. Analytical cross-sectional studies, case-control studies, case reports, case series, randomized clinical trials and systematic literature reviews were included in the search—other types of studies were excluded. A comprehensive list of MeSH and non-MeSH terms including gastroesophageal reflux, obesity, digestive system surgical procedures, overweight, MSA, Linx, Linx procedure and Linx antireflux procedure were used to create basic search algorithms.

Two authors screened the title and abstract of the search results to find relevant studies. The full text of all articles of potential interest was retrieved and verified for relevance based on specified relevance criteria. Only articles that compared outcomes associated with the MSA procedure between obese and non-obese patients were included; studies related to other types of antireflux surgical procedures or post-bariatric interventions as well as duplicated papers were excluded. As this was a non-systematic literature review, it was not necessary to register a protocol in the PROSPERO database. No statistical analyses were performed, and no tabular synthesis was required for the information extraction. The PRISMA-2020 checklist was used as a guide to review the content of the manuscript.

RESULTS

Using the previously described mixed-search strategy, 27 articles were identified, and 22 articles were excluded: 16 of these were related to the placement of the Linx device after bariatric surgeries, 4 were not directly related to the search, 1 was not related to the outcomes previously established and 1 corresponded to an expert consensus using the Delphi methodology (Figure 1).

Thus, five articles were included: three of these studies did not identify a statistically significant difference in outcomes based on BMI, and the remaining two studies identified a high BMI as a factor for worse outcomes after MSA.

James et al.11 performed a retrospective cohort study on patients who had laparoscopic MSA from 2016 to 2019. Patients were classified into cohorts based on BMI (<25 kg/m2 normal weight, 25–29.9 kg/m2 overweight, 30–34.9 kg/m2 obese class I and > 35 kg/m2 obese class II-III). The study followed up with 361 of 621 patients who underwent the procedure with a median follow-up of 15.4 months. GERD symptoms were measured using DeMeester scores and GERD-Health Related Quality of Life (HRQL) scores. No significant differences between the four patient groups were found.9

Similarly, Ayazi et al.12 reported a retrospective, observational single-center study of 553 patients with a mean BMI of 29.0 kg/m2 and a mean follow-up of 10.3 months. A favorable outcome after MSA was defined as freedom from proton pump inhibitors and a 50% improvement in GERD-HRQL total score. Univariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated that a BMI equal to or greater than 30 kg/m2 was not significantly associated with worse outcomes after MSA (OR = 1.04, 95% CI: 0.59–1.83, P = 0.8943).

In a study conducted by Ferrari et al.13 that included 335 patients who underwent MSA and were followed for 6–12 years, a BMI of less than 25 kg/m2 was not directly related to the success of the procedure after running a univariate logistic regression model (P = 0.361). The success of the outcome in this study was also defined as freedom from proton pump inhibitors and a 50% improvement in GERD-HRQL total score.

Warren et al.3 completed a retrospective review to identify factors predisposing favorable outcomes after MSA placement. The study followed 170 of 198 patients who underwent MSA for GERD from 2009 to 2015 with a median follow-up of 48 months; both univariable and multivariable analyses showed that outcomes were negatively impacted by BMI (OR = 0.05, 95% CI: 0.003–0.78; P = 0.03). This study suggests that a BMI over 35 kg/m2 may be associated with worse outcomes after MSA.3

Another retrospective review of prospectively collected data of 334 patients with reflux disease was performed by Schwameis et al.6 between 2013 and 2017. This article mentioned that GERD recurrence was correlated with a higher BMI; however, statistical analyses related to this variable were not described and a BMI range was not specified. A comprehensive summary of the results from the reviewed studies, including demographics, surgical characteristics, GERD-HRQL scores, and pH-monitoring parameters before and after MSA, is presented in Table 1.

Population characteristics and summary of GERD-HRQL scores and pH-monitoring parameters before and after MSA of included studies

| Author . | Warren et al.9 . | Ayazi et al.12 . | Ferrari et al.13 . | Schwameis et al.6 . | James et al.11,† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | USA | USA | Italy | USA | USA |

| Year | 2017 | 2020 | 2020 | 2021 | 2021 |

| Total subjects, no. | 198 | 553 | 335 | 334 | 621 |

| Male sex, % | 49.0 | 38.2 | 66.2 | 39.8 | 48.5 |

| Age, years | 53 (43–60)‡ | 54.7 (13.9)§ | F/U < 6 years: 46 (20)§ F/U > 6 years: 44 (20.8)§ | 53.1 (13.8)§ | Group 1: 59.5 (17.3)§ Group 2: 60.9 (12.5)§ Group 3: 58.7 (13.4)§ Group 4: 59.8 (11.7)§ |

| BMI, kg/m 2 | 27 (24–30)‡ | 29.0 (4.6)§ | F/U < 6 years: 25.4 (5)§ F/U > 6 years: 23.9 (4.5)§ | 29.1 (4.7)§ | Group 1: 22.6 (1.9)§ Group 2: 27.4 (1.5)§ Group 3: 32.1 (1.4)§ Group 4: 38.2 (2.8)§ |

| Subjects with complete follow-up, no. | 170¶ | 251¶ | F/U > 6 years: 124¶ | 334¶ | Group 1: 97¶ Group 2: 144¶ Group 3: 89¶ Group 4: 31¶ |

| Follow-up, months | 48 (19–60)‡ | 10.3 (10.6)§ | 9 years (2)‡ | 13.6 (10.4)§ | 15.4 (9.7–24.4)‡ |

| Patients with hiatal hernia, no. (%) | 109 (64.1) | 455 (82.3) | 260 (77.6) | 240 (71.9) | 361 (100)¶ |

| Patients with hiatal hernia > 4 cm or PEH, no. (%) | 3 (1.8) | 32 (5.8) | 30 (8.9) | 69 (20.7) | Unk |

| Hiatal closure, no. (%) | 67 (39.4) | If HH, routine cruroplasty | Minimal or formal posterior crura repair depending of HH size | If HH, routine cruroplasty | If HH, routine cruroplasty |

| Pre-operative DeMeester score | 37.9 (27.9–51.2)‡ | 33.9 (29.4)§ | F/U > 6 years: 40.7 (26.5)§ ¶ | 31.3 (31.2)§ | Group 1: 37.0 (24.4–49.4)‡ Group 2: 44.0 (31.6–63.1)‡ Group 3: 44.6 (30.3–66.7)‡ Group 4: 47.9 (34.3–70.0)‡ |

| Pre-operative GERD-HRQL score | 26 (19–31)‡ | 33.8 (18.7)§ | F/U > 6 years: 19.9¶ | Unk | Group 1: 21 (11–31)‡ Group 2: 23 (15–31)‡ Group 3: 27 (17–34)‡ Group 4: 23 (18–29)‡ |

| Post-operative DeMeester score | 15.6 (5.8–26.6)‡ | Size 13–14: 7.2 (10.2)§ Size 15: 18.8 (33.2)§ Size 16–17: 21.0 (42.8)§ | F/U > 6 years: 16.3 (18.8)§ ¶ | 13.9 (30.6)§ | Group 1: 13.9 (5.3–48.0)‡ ¶ Group 2: 15.5 (5.0–41.9)‡ ¶ Group 3: 16.8 (2.4–34.5)‡ ¶ Group 4: 6.8 (4.5–32.4)‡ ¶ |

| Post-operative GERD-HRQL score | 5 (2–10)‡ | Size 13–14: 9.0 (11.1)§ Size 15: 6.0 (7.7)§ Size 16–17: 5.7 (8.3)§ | F/U > 6 years: 4.01¶ | Unk | Group 1: 5 (2–12)‡ ¶ Group 2: 4 (1–11)‡ ¶ Group 3: 5 (2–12)‡ ¶ Group 4: 7 (1–11)‡ ¶ |

| Author . | Warren et al.9 . | Ayazi et al.12 . | Ferrari et al.13 . | Schwameis et al.6 . | James et al.11,† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | USA | USA | Italy | USA | USA |

| Year | 2017 | 2020 | 2020 | 2021 | 2021 |

| Total subjects, no. | 198 | 553 | 335 | 334 | 621 |

| Male sex, % | 49.0 | 38.2 | 66.2 | 39.8 | 48.5 |

| Age, years | 53 (43–60)‡ | 54.7 (13.9)§ | F/U < 6 years: 46 (20)§ F/U > 6 years: 44 (20.8)§ | 53.1 (13.8)§ | Group 1: 59.5 (17.3)§ Group 2: 60.9 (12.5)§ Group 3: 58.7 (13.4)§ Group 4: 59.8 (11.7)§ |

| BMI, kg/m 2 | 27 (24–30)‡ | 29.0 (4.6)§ | F/U < 6 years: 25.4 (5)§ F/U > 6 years: 23.9 (4.5)§ | 29.1 (4.7)§ | Group 1: 22.6 (1.9)§ Group 2: 27.4 (1.5)§ Group 3: 32.1 (1.4)§ Group 4: 38.2 (2.8)§ |

| Subjects with complete follow-up, no. | 170¶ | 251¶ | F/U > 6 years: 124¶ | 334¶ | Group 1: 97¶ Group 2: 144¶ Group 3: 89¶ Group 4: 31¶ |

| Follow-up, months | 48 (19–60)‡ | 10.3 (10.6)§ | 9 years (2)‡ | 13.6 (10.4)§ | 15.4 (9.7–24.4)‡ |

| Patients with hiatal hernia, no. (%) | 109 (64.1) | 455 (82.3) | 260 (77.6) | 240 (71.9) | 361 (100)¶ |

| Patients with hiatal hernia > 4 cm or PEH, no. (%) | 3 (1.8) | 32 (5.8) | 30 (8.9) | 69 (20.7) | Unk |

| Hiatal closure, no. (%) | 67 (39.4) | If HH, routine cruroplasty | Minimal or formal posterior crura repair depending of HH size | If HH, routine cruroplasty | If HH, routine cruroplasty |

| Pre-operative DeMeester score | 37.9 (27.9–51.2)‡ | 33.9 (29.4)§ | F/U > 6 years: 40.7 (26.5)§ ¶ | 31.3 (31.2)§ | Group 1: 37.0 (24.4–49.4)‡ Group 2: 44.0 (31.6–63.1)‡ Group 3: 44.6 (30.3–66.7)‡ Group 4: 47.9 (34.3–70.0)‡ |

| Pre-operative GERD-HRQL score | 26 (19–31)‡ | 33.8 (18.7)§ | F/U > 6 years: 19.9¶ | Unk | Group 1: 21 (11–31)‡ Group 2: 23 (15–31)‡ Group 3: 27 (17–34)‡ Group 4: 23 (18–29)‡ |

| Post-operative DeMeester score | 15.6 (5.8–26.6)‡ | Size 13–14: 7.2 (10.2)§ Size 15: 18.8 (33.2)§ Size 16–17: 21.0 (42.8)§ | F/U > 6 years: 16.3 (18.8)§ ¶ | 13.9 (30.6)§ | Group 1: 13.9 (5.3–48.0)‡ ¶ Group 2: 15.5 (5.0–41.9)‡ ¶ Group 3: 16.8 (2.4–34.5)‡ ¶ Group 4: 6.8 (4.5–32.4)‡ ¶ |

| Post-operative GERD-HRQL score | 5 (2–10)‡ | Size 13–14: 9.0 (11.1)§ Size 15: 6.0 (7.7)§ Size 16–17: 5.7 (8.3)§ | F/U > 6 years: 4.01¶ | Unk | Group 1: 5 (2–12)‡ ¶ Group 2: 4 (1–11)‡ ¶ Group 3: 5 (2–12)‡ ¶ Group 4: 7 (1–11)‡ ¶ |

†Grouping was done according body mass index (BMI), group 1: <24.9 kg/m2; group 2: 25–29.9 kg/m2; group 3: 30–34.9 kg/m2: group 4: >35 kg/m2

‡Median, interquartile range

§Mean, standard deviation

¶Data from patients with complete follow-up

Abbreviations: F/U, follow-up; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; GERD-HRQL, GERD-Health Related Quality of Life Questionnaire; PEH, paraesophageal hernia; Unk, unknown data

Population characteristics and summary of GERD-HRQL scores and pH-monitoring parameters before and after MSA of included studies

| Author . | Warren et al.9 . | Ayazi et al.12 . | Ferrari et al.13 . | Schwameis et al.6 . | James et al.11,† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | USA | USA | Italy | USA | USA |

| Year | 2017 | 2020 | 2020 | 2021 | 2021 |

| Total subjects, no. | 198 | 553 | 335 | 334 | 621 |

| Male sex, % | 49.0 | 38.2 | 66.2 | 39.8 | 48.5 |

| Age, years | 53 (43–60)‡ | 54.7 (13.9)§ | F/U < 6 years: 46 (20)§ F/U > 6 years: 44 (20.8)§ | 53.1 (13.8)§ | Group 1: 59.5 (17.3)§ Group 2: 60.9 (12.5)§ Group 3: 58.7 (13.4)§ Group 4: 59.8 (11.7)§ |

| BMI, kg/m 2 | 27 (24–30)‡ | 29.0 (4.6)§ | F/U < 6 years: 25.4 (5)§ F/U > 6 years: 23.9 (4.5)§ | 29.1 (4.7)§ | Group 1: 22.6 (1.9)§ Group 2: 27.4 (1.5)§ Group 3: 32.1 (1.4)§ Group 4: 38.2 (2.8)§ |

| Subjects with complete follow-up, no. | 170¶ | 251¶ | F/U > 6 years: 124¶ | 334¶ | Group 1: 97¶ Group 2: 144¶ Group 3: 89¶ Group 4: 31¶ |

| Follow-up, months | 48 (19–60)‡ | 10.3 (10.6)§ | 9 years (2)‡ | 13.6 (10.4)§ | 15.4 (9.7–24.4)‡ |

| Patients with hiatal hernia, no. (%) | 109 (64.1) | 455 (82.3) | 260 (77.6) | 240 (71.9) | 361 (100)¶ |

| Patients with hiatal hernia > 4 cm or PEH, no. (%) | 3 (1.8) | 32 (5.8) | 30 (8.9) | 69 (20.7) | Unk |

| Hiatal closure, no. (%) | 67 (39.4) | If HH, routine cruroplasty | Minimal or formal posterior crura repair depending of HH size | If HH, routine cruroplasty | If HH, routine cruroplasty |

| Pre-operative DeMeester score | 37.9 (27.9–51.2)‡ | 33.9 (29.4)§ | F/U > 6 years: 40.7 (26.5)§ ¶ | 31.3 (31.2)§ | Group 1: 37.0 (24.4–49.4)‡ Group 2: 44.0 (31.6–63.1)‡ Group 3: 44.6 (30.3–66.7)‡ Group 4: 47.9 (34.3–70.0)‡ |

| Pre-operative GERD-HRQL score | 26 (19–31)‡ | 33.8 (18.7)§ | F/U > 6 years: 19.9¶ | Unk | Group 1: 21 (11–31)‡ Group 2: 23 (15–31)‡ Group 3: 27 (17–34)‡ Group 4: 23 (18–29)‡ |

| Post-operative DeMeester score | 15.6 (5.8–26.6)‡ | Size 13–14: 7.2 (10.2)§ Size 15: 18.8 (33.2)§ Size 16–17: 21.0 (42.8)§ | F/U > 6 years: 16.3 (18.8)§ ¶ | 13.9 (30.6)§ | Group 1: 13.9 (5.3–48.0)‡ ¶ Group 2: 15.5 (5.0–41.9)‡ ¶ Group 3: 16.8 (2.4–34.5)‡ ¶ Group 4: 6.8 (4.5–32.4)‡ ¶ |

| Post-operative GERD-HRQL score | 5 (2–10)‡ | Size 13–14: 9.0 (11.1)§ Size 15: 6.0 (7.7)§ Size 16–17: 5.7 (8.3)§ | F/U > 6 years: 4.01¶ | Unk | Group 1: 5 (2–12)‡ ¶ Group 2: 4 (1–11)‡ ¶ Group 3: 5 (2–12)‡ ¶ Group 4: 7 (1–11)‡ ¶ |

| Author . | Warren et al.9 . | Ayazi et al.12 . | Ferrari et al.13 . | Schwameis et al.6 . | James et al.11,† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | USA | USA | Italy | USA | USA |

| Year | 2017 | 2020 | 2020 | 2021 | 2021 |

| Total subjects, no. | 198 | 553 | 335 | 334 | 621 |

| Male sex, % | 49.0 | 38.2 | 66.2 | 39.8 | 48.5 |

| Age, years | 53 (43–60)‡ | 54.7 (13.9)§ | F/U < 6 years: 46 (20)§ F/U > 6 years: 44 (20.8)§ | 53.1 (13.8)§ | Group 1: 59.5 (17.3)§ Group 2: 60.9 (12.5)§ Group 3: 58.7 (13.4)§ Group 4: 59.8 (11.7)§ |

| BMI, kg/m 2 | 27 (24–30)‡ | 29.0 (4.6)§ | F/U < 6 years: 25.4 (5)§ F/U > 6 years: 23.9 (4.5)§ | 29.1 (4.7)§ | Group 1: 22.6 (1.9)§ Group 2: 27.4 (1.5)§ Group 3: 32.1 (1.4)§ Group 4: 38.2 (2.8)§ |

| Subjects with complete follow-up, no. | 170¶ | 251¶ | F/U > 6 years: 124¶ | 334¶ | Group 1: 97¶ Group 2: 144¶ Group 3: 89¶ Group 4: 31¶ |

| Follow-up, months | 48 (19–60)‡ | 10.3 (10.6)§ | 9 years (2)‡ | 13.6 (10.4)§ | 15.4 (9.7–24.4)‡ |

| Patients with hiatal hernia, no. (%) | 109 (64.1) | 455 (82.3) | 260 (77.6) | 240 (71.9) | 361 (100)¶ |

| Patients with hiatal hernia > 4 cm or PEH, no. (%) | 3 (1.8) | 32 (5.8) | 30 (8.9) | 69 (20.7) | Unk |

| Hiatal closure, no. (%) | 67 (39.4) | If HH, routine cruroplasty | Minimal or formal posterior crura repair depending of HH size | If HH, routine cruroplasty | If HH, routine cruroplasty |

| Pre-operative DeMeester score | 37.9 (27.9–51.2)‡ | 33.9 (29.4)§ | F/U > 6 years: 40.7 (26.5)§ ¶ | 31.3 (31.2)§ | Group 1: 37.0 (24.4–49.4)‡ Group 2: 44.0 (31.6–63.1)‡ Group 3: 44.6 (30.3–66.7)‡ Group 4: 47.9 (34.3–70.0)‡ |

| Pre-operative GERD-HRQL score | 26 (19–31)‡ | 33.8 (18.7)§ | F/U > 6 years: 19.9¶ | Unk | Group 1: 21 (11–31)‡ Group 2: 23 (15–31)‡ Group 3: 27 (17–34)‡ Group 4: 23 (18–29)‡ |

| Post-operative DeMeester score | 15.6 (5.8–26.6)‡ | Size 13–14: 7.2 (10.2)§ Size 15: 18.8 (33.2)§ Size 16–17: 21.0 (42.8)§ | F/U > 6 years: 16.3 (18.8)§ ¶ | 13.9 (30.6)§ | Group 1: 13.9 (5.3–48.0)‡ ¶ Group 2: 15.5 (5.0–41.9)‡ ¶ Group 3: 16.8 (2.4–34.5)‡ ¶ Group 4: 6.8 (4.5–32.4)‡ ¶ |

| Post-operative GERD-HRQL score | 5 (2–10)‡ | Size 13–14: 9.0 (11.1)§ Size 15: 6.0 (7.7)§ Size 16–17: 5.7 (8.3)§ | F/U > 6 years: 4.01¶ | Unk | Group 1: 5 (2–12)‡ ¶ Group 2: 4 (1–11)‡ ¶ Group 3: 5 (2–12)‡ ¶ Group 4: 7 (1–11)‡ ¶ |

†Grouping was done according body mass index (BMI), group 1: <24.9 kg/m2; group 2: 25–29.9 kg/m2; group 3: 30–34.9 kg/m2: group 4: >35 kg/m2

‡Median, interquartile range

§Mean, standard deviation

¶Data from patients with complete follow-up

Abbreviations: F/U, follow-up; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; GERD-HRQL, GERD-Health Related Quality of Life Questionnaire; PEH, paraesophageal hernia; Unk, unknown data

DISCUSSION

MSA is an effective procedure for chronic GERD and an alternative to LARS. Chronic GERD symptoms are often worse in obese patients. In this literature review, we found five papers that studied MSA outcomes in overweight and obese patients. However, the results are contradictory. James et al.,11 Ferrari et al.13 and Ayazi et al.12 found no difference in MSA outcomes between normal, overweight and obese patients, whereas Warren et al.3 and Schwameis et al.6 found that a higher BMI negatively impacted outcomes after MSA. The limited research available and inconsistent conclusions support the need for additional investigation.

One potential mechanism of GERD persistence or recurrence in overweight and obese patients after MSA is the severity of the disease prior to the procedure. Obese patients are more likely to have a hiatal hernia, higher inadequate esophageal acid clearance, a structurally defective LES and increased LES relaxation.3,4 These prior conditions, associated with a higher DeMeester score, could cause the device to be less effective. Further research should consider that central obesity is a greater predisposing factor to GERD than high BMI alone. Therefore, it may be preferential to measure the waist-to-hip ratio with regard to MSA outcomes.

CONCLUSION

The gap in knowledge related to predictors of the success or failure of MSA is evident. There is a lack of information regarding outcomes in overweight and obese patients after MSA. To date, only retrospective observational studies have been carried out and the results are discordant between them. More research is needed to better understand treatment options for GERD in this patient population.

SUPPLEMENT SPONSORSHIP

This supplement is sponsored by Ethicon Endo-Surgery.

Conflicts of interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.