-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Uwe Hasebrink, Lisa Merten, Julia Behre, Public connection repertoires and communicative figurations of publics: conceptualizing individuals’ contribution to public spheres, Communication Theory, Volume 33, Issue 2-3, May-August 2023, Pages 82–91, https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtad005

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

As public sphere(s) have been ascribed core functions for democratic societies, correlating theories have a long tradition in communications research. Yet they often fail to bridge the conceptual gap between the macro level of public sphere(s) and the micro level of individual citizens. In this article, we propose a conceptual approach that helps to describe and explain the contribution of individuals to the construction of publics. Following Elias’ figurational approach, we propose a framework for the analysis of different kinds of publics as communicative figurations. To capture individuals’ contribution to these publics, we introduce the concept of public connection repertoires which represent individuals’ structured patterns of connection to different publics. This results in the figurational analysis of publics, based on the public repertoires of all individuals who connect to that public. We discuss implications of this approach for theoretical work on public spheres in changing media environments.

Introduction

Democratic theory positions the public sphere as a central component of a functional democratic model of society (Dahlgren, 2009; Ferree et al., 2002; Habermas, 1989 [1962]; Lunt & Livingstone, 2013). In terms of the constitution of public spheres, different versions of democratic theory—e.g., liberal, participatory, and deliberative (Ferree et al., 2002)—share a normative approach to citizens and their contribution to the functioning of public spheres. While the expectations of how exactly citizens should contribute to public spheres differ between the theories (Beaufort, 2020), the ideal of an “informed” or “engaged” citizen provides a common ground in theoretical writings. As demonstrated in recent research (e.g., Ytre-Arne & Moe, 2018), this vague ideal falls short of capturing the complexity and diversity of the role of citizens in the construction of public spheres and of understanding recent societal developments that challenge normative expectations. For instance, substantial parts of the population seem to turn away from public issues and to avoid news (Gurr & Metag, 2021; Newman et al., 2022). In many countries, voter turnout is declining (International IDEA, 2016, p. 25). The emergence of highly differentiated social milieus elicits concerns about an increasing fragmentation of public spheres and a loss of their integrative function (Fletcher & Nielsen, 2017; Webster & Ksiazek, 2012). The assumed consensus that public spheres are inclusive spaces for the exchange about and the deliberation of issues of public concern is denounced by some societal groups that distrust the media in a fundamental way (Flew, 2021; Newman et al., 2022). Finally, due to the eminent role of the media in the construction of public spheres, there are intense debates about the implications of current changes in the media environment that question key assumptions of former public sphere theories (Habermas, 2022; Staab & Thiel, 2022). One important aspect of these changes is the new role of individual citizens: In the digital world, those who were previously conceptualized mainly in their role as (mass) audiences, have become active participants in public debates—at least some of them (Rosen, 2006).

To better understand recent transformations of public spheres, this article focuses on the role of individuals, often conceived on the aggregate level of “citizen audiences” or “the public.” We develop a conceptual approach that helps to describe and understand how individuals: (a) connect themselves to different public spheres; and (b) by doing so, contribute to the construction of these public spheres. In the first part, we will briefly review the research on public spheres concerning the respective conceptualizations of the role of individuals and, on this basis, specify the objectives of our approach. In the second part, we apply a figurational approach to the analysis of public spheres, conceptualizing them as communicative figurations. In the third part, within this general framework, we conceptualize individuals’ practices of relating themselves to publics as “public connection repertoires” and discuss options for the empirical operationalization of these repertoires. In the fourth part, we demonstrate how this conceptual approach can help to describe the constitution of public spheres. Finally, we discuss the implications of our approach for public sphere theory in general.

The individual in public sphere theories

The aggregated “public” of the public sphere

Given our objective to develop a conceptual framework for analyzing the contribution of individual citizens to public spheres, we begin with a brief outline of relevant lessons to be learnt from academic debates. One common ground for different approaches is the postulation that public spheres are based on interactions, on communicative practices, and on discourse (Habermas, 1989 [1962]). Deviating from a primarily normative understanding of the public sphere, which has been criticized for limiting the concept to spaces for well-educated, male citizens in Western democracies, a more open approach to existing public spheres has been proposed (Fraser, 1990; Lunt & Livingstone, 2013). As communicative constructions, public spheres are highly dynamic; therefore, we need an approach that allows us to empirically capture different forms of public spheres and their changes. This is even more important because recent media developments have led to blurring boundaries between “the public” and “the private” (Klinger, 2018). Furthermore, the approach has to be sensitive not only to the factors that assure the homogeneity and coherence of a public sphere, but also to inner dissonances and conflicts (Pfetsch et al., 2018). Therefore, research on public spheres requires an actor-centered approach that takes different types of actor roles into account.

Existing research on public spheres focuses primarily on institutionalized actors, such as the political-administrative system, interest groups as well as media organizations and journalism, who define and distribute issues for public debate (Donges & Jarren, 2010). Surprisingly enough, the role of individual citizens and media users has not been the focus, although the everyday understanding of “the public” refers to citizen audiences. It is the individual citizen, who observes politics and all other domains of public interest, who makes use of media coverage on public issues, and who participates in private and public conversations and debates about these issues. Compared to a wide range of normative expectations concerning the citizens and their expected contribution to public spheres, there is a lack of theoretical work that takes the perspective of citizens as individuals within their everyday lives.

In most cases, citizens are characterized by aggregate indicators, e.g., the reach of certain media or the prevalence of certain ways to participate in public life. Following the repertoire-oriented approach to media use (Bjur et al., 2014; Hasebrink & Popp, 2006), research on public spheres should not be limited to one particular type of media, for instance, “television” (Aufderheide, 1991; Price & Price 1995), or “digital media” (Cohen & Fung 2021; Papacharissi, 2002) but should analyze the interplay between different types of media. This will help to overcome a research gap as intra-individual differences have largely been neglected—for instance, the possibility that an individual can perform different ways of engaging with the public world in everyday life. The recent “audience turn” in journalism studies (Swart et al., 2022) has led to increasing evidence of how audiences make use of journalistic content; but it still tends to focus on aggregates—“audiences”—instead of individuals and on the use of news media instead of a wider range of communicative practices in everyday life. In following Swart et al. (2022) and their plea for a more radical audience turn in journalism studies, we regard the perspective of individuals and their contribution to public spheres as a particularly relevant element in theorizing (transformations of) public spheres.

The plurality of public spheres

The “public sphere” is often constructed as a singular phenomenon with the national public sphere as the (implicit) point of reference. However, there are many reasons to argue that there are different kinds of public spheres (Dahlgren, 2005). While the idea of plural public spheres has been increasingly proposed in theoretical writings (Breese, 2011; Dahlgren, 2005; Fraser, 1990), it is often linked with the assumption that this leads to societal fragmentation (Downey & Fenton, 2003; Galston, 2003). However, the underlying assumption that individuals relate themselves to only one public sphere, needs to be questioned: Empirical research that sets out to reconstruct individuals’ practices in their everyday life suggests that individuals engage in several publics (Breese, 2011), often through their practices of media use. Through their everyday media use, individuals may become members of different publics in our current media environment of multiple choices (Van Aelst et al., 2017). Research on the overlap of issue agendas across networked public spheres has shown that issues travel from the traditional press to social media and vice versa, but also across social media communities, reaching members of different publics and thus connecting individual media users to communities beyond a single public (Mao et al., 2022; Rogstad, 2016). Moreover, existing conceptualizations neglect inter-individual differences in how citizens engage with public spheres; the narrow focus on some normative criteria of civic engagement and their assessment—for instance, do individuals engage in political discussions, or not? (Boulianne, 2015; Ohme, 2019; Theocharis & Quintelier, 2016)—obstructs the view on empirical observations that there is a wide range of practices to engage in and contribute to public spheres.

Against the background of these arguments, our conceptual approach to public spheres is intended to help describe and understand individuals' contributions to the construction of publics. In the first step, we propose a conceptual framework for analyzing different types of publics. In the second step, we turn to the individual level of analysis and elaborate on the concept of public connection.

A figurational approach to the analysis of public spheres

Towards a figurational definition of publics

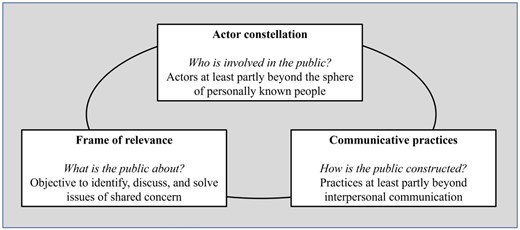

In order to develop our approach, we step back from the particularities of existing concepts of public spheres and their underlying normative models of democracy. Therefore, in the following, we will use the more abstract term “publics” instead of the rather theory-loaded term “public spheres.” The idea is to develop a conceptual framework that allows for the empirical analysis of any public from the perspective of individuals involved in that public. For this purpose, we refer to Elias’ concept of “figurations” (1978): We regard publics as social domains that are communicatively constructed and can be analyzed as communicative figurations (Hepp & Hasebrink, 2018). This figurational approach makes it possible to carry out empirical analyses of publics that reflect their structure and process dynamics. From this point of view, each public is: (a) constructed by a certain constellation of actors with different roles; (b) it includes certain frames of relevance that define what this public means to the actors involved; and (c) it is made up of ongoing communicative practices.

Ad (a): Each public is constructed by a particular constellation of actors who play a variety of roles, e.g., journalists, scientists, amateur experts on certain topics expressing their opinions, and the various audience roles a public might adopt (Ferree et al., 2002). A public’s constellation of actors typically includes three types of actors: (1) those who are observed because, for a variety of reasons, they are generally considered to be influential, e.g., politicians, public administrators, companies, intellectuals, “stars” in the areas of sports or popular culture; (2) those who observe the first type of actors on a professional basis and publish their observations to inform the public, e.g., journalists; and (3) those who observe the first type of actors, often based on the information imparted by professional observers, in order to inform themselves about topics of public concern and form an opinion. The third set of actors is in the focus of our article. However, we have to stress that this distinction is an analytical one: It refers to basic roles and not to actual individuals. Any individual can play a variety of roles. As mentioned above, current changes in the media environment tend to blur the boundaries between these roles: “the people formerly known as the audience” (Rosen, 2006) can easily become publishers themselves or perform a role that is observed by a public (Loosen & Schmidt, 2012). The examination of publics from the perspective of this third group—the non-professional observers—needs to consider the extent, to which roles can be switched and how members of this public perceive its actor constellation, who they regard as actors of public interest, who they consider trustworthy professional observers, and who they relate to as their co-audience.

Ad (b): A public includes certain frames of relevance that define what this public means for the actors involved. The frame of relevance for the “general” public sphere as originally conceptualized, e.g., in a Habermasian understanding, refers to a space in which all citizens inform themselves and deliberate about issues of public concern (Lunt & Livingstone, 2013). Concerning individual citizens, this frame includes the normative expectation to be informed about issues of public concern; thus, it goes along with the so-called duty to keep informed (McCombs & Poindexter, 1983). Beyond these general publics, a large number of specific publics with specific frames of relevance have been investigated from a variety of academic perspectives, for instance, counter publics representing marginalized groups, or specialized publics of people who share a strong interest in a specific topic, e.g., certain policy areas, scientific disciplines, forms of culture, or hobbies (Fossum & Schlesinger, 2007; Korobkova & Rafalow, 2016; Mourao et al., 2015; Risse, 2014; Sha, 2006; Sandvoss, 2007).

Ad (c): A public is made up of ongoing communicative practices that are entangled with a much broader media ensemble than they used to be only a few years ago (Hasebrink & Hepp, 2017). For those publics that go beyond the local, research assumes an eminent role for journalistic media outlets offered by television, radio, newspapers, printed magazines, and, for the past two decades, the Internet (Hölig et al., 2022; Newman et al., 2022). Modern societies are complex, this complexity means that citizens will rely on journalists to keep them informed on current affairs. However, there is plenty of research that emphasizes the important role of interpersonal communication in individuals’ information-gathering practices concerning current issues of public concern (Newman et al., 2022).

Using these three categories that constitute figurations, we arrive at a general definition of publics. The characteristics of publics that distinguish them from other social entities are: (a) an actor constellation that extends beyond the sphere of personally known people; (b) the objective to identify, discuss, and solve issues of shared concern as a frame of relevance; and (c) communicative practices that go, at least partly, beyond interpersonal communication. Figure 1 illustrates this first element of our conceptual framework.

Three types of publics

The general definition of publics leaves room for a wide range of different publics with different figurations. For the purpose of our conceptual approach, we distinguish three types of publics that are characterized by specific principles that lead to the construction of publics: polities, topics, and groups.

Polity publics refer to a geo-political space and a political system, in which citizens inform themselves and deliberate on issues that are regarded as relevant to that respective geo-political space (Lunt & Livingstone, 2013). They can be differentiated along the scale of geo-political entities, for example, (sub-)local, regional, national, transnational, or even global publics. They are based on constitutional and administrative rules and definitions that specify the actor constellation (e.g., who is a citizen of the political entity, and who can participate in elections?), the frames of relevance (political objectives and values of that entity, e.g., constitutional rules, or the expectation that all individuals keep themselves informed and build their own opinion), and the (communicative) practices (e.g., the use of certain media, elections, conventions, and other forms of participation related to the political entity). In previous research, theoretical discourses about public spheres often referred to this kind of public. One important characteristic of these publics is the normative assumption that all individuals are part of the public of the city, or state, in which they live. In this sense, it is not an issue of individual choice to belong to the respective polity publics. Taking up the distinction between different levels of information needs, individuals’ information practices within polity publics are mainly based on “undirected information needs” (Hasebrink, 2017). These needs represent people’s desire to stay informed about the news agenda that is relevant to their polity public. Undirected information needs do not lead to seeking particular information, but to the monitoring of the environment for upcoming new issues that are relevant to the individual’s relevant polity public(s). In complex societies, journalism is the main instrument for satisfying this need—providing news on issues that are considered relevant to the respective public, independent of individual interests and orientations.

Topic publics are based on individual orientations and preferences concerning certain topics or subject areas; any aspect that might be relevant to this topic and contribute to expertise in this subject area defines the frame of relevance. The actor constellation includes all individuals who share interest and expertise in this topic. Their communicative practices are mainly based on all kinds of media that specialize in the respective topic. While polity publics are, at least in a normative sense, inclusive and open to all citizens of a geo-political entity, topic publics are an expression of selectivity: Individuals differ in their interests; thus, a topic public is defined by the distinction between those who are interested in the topic, and those who are not. Therefore, according to the classification of information needs mentioned above, topic publics are mainly based on “thematic interests” (Hasebrink, 2017) which leads individuals to seek out specific information media dealing with their respective field of interest. These are active orientations towards certain topics and aspects of life. In this respect, people tend to specialize, to acquire certain expertise, and to distinguish themselves from others. In this area, people differ dramatically and as a result, many different forms of targeted communication and specialized media channels have been developed.

Group publics are based on specific aspects of an individuals’ identity (e.g., gender, ethnic background, or a particular chronic disease or disability) that are so relevant that individuals have strong feelings of belonging to the group of people who share this aspect of their identity. With this actor constellation, any aspect that might be relevant to this group and strengthen the respective identity defines the frame of relevance. Again, this kind of public is based on specific information needs: “Group-related needs” (Hasebrink, 2017) emphasizes people’s desire to know what their reference groups think about the world and themselves. The exchange within these groups, including the discussion of common interests and objectives leading to trust and feelings of belonging, is a core factor of community-building and thus an important prerequisite for an individual’s identity and position in society. Before the digital age, this kind of information need was mainly fulfilled through personal networks, face-to-face communication, or personal forms of media-based communication, such as letters and phones. The new communication services offered by social media significantly increase the opportunities for communications practices that serve group-related needs and the constitution of group publics.

Hybrid publics

We must emphasize that the three types of publics presented here are based on analytical distinctions. In the empirical world, polity publics, topic publics, and group publics may overlap and form hybrid publics. For instance, the so-called “issue publics,” which have been extensively studied in the field of political communication (Bennett et al., 2015; Bolsen & Leeper, 2013; Krosnick, 1990), represent a combination of characteristics of polity publics and topic publics. When current issues of public concern prove to be particularly relevant and secular, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Merten et al., 2022b), a specific issue public emerges from the general polity public; as long as the issue is unresolved, the issue public includes members of the local, regional, national, and global polity publics who develop a specific interest in the topic, and members of existing topic publics who were already interested in the scientific, social, economic, and political details of pandemics in general. Depending on the respective issue, issue publics can also emerge from group publics; for instance, the issue “Black Lives Matter” combined group publics of the groups concerned, and polity publics around the world (Dunklin & Jennings, 2022; Edrington, 2022). As the examples illustrate, our distinction does not correspond to the distinction between political and non-political issues. The area of interest of a topic public can be a specific policy area; the salient characteristic of a group public can be highly political, for instance, belonging to a minority group that fights for recognition.

Scalability of publics

One of the affordances of the concept of communicative figurations is its scalability: It allows for analyzing “figurations of figurations” (Hepp & Hasebrink, 2018). As for publics as figurations, an illustrative example is the relationship between polity publics on the level of boroughs, cities, regions, national states, and supranational entities. Publics on one specific level are constituted in part by publics at the higher and/or lower levels, which bring in their actor constellations, frames of relevance and communicative practices. This reflects the political, administrative, and social interrelations between different geo-political spaces. Likewise, figurations of topic and group publics are influenced by polity publics and at the same time influence them. One might consider a progressing process of abstraction that leads to a “general public,” that is, a figuration that includes all other publics on more specific levels. This abstract figuration of figurations comes close to the idea of “the public” as a singular phenomenon that has been discussed above.

Regarding the objective of this article, the proposed conceptualization of publics as communicative figurations shall help to reconstruct individuals’ contribution to the construction of publics. We assume that each individual can contribute to different types of publics and that these multiple belongings have important implications for the construction of specific publics, and of the abstract general public. Before we discuss these implications, we need to specify the ways in which individuals contribute to publics.

Individuals’ contribution to the construction of publics

Public connection

One type of actor in the actor constellation of publics are individuals who, as citizens of a polity public, or as members of a particular topic or group public, are in some way involved in these publics. To conceptualize the role of individuals in the construction of publics, we refer to the concept of public connection (e.g., Hovden and Moe, 2017; Kaun, 2012; Moe & Ytre-Arne, 2022; Swart et al., 2017a, 2017b). As Couldry et al. (2007, p. 3) have argued, “as citizens, we share an orientation to a public world where matters of shared concern are, or at least should be, addressed.” The concept of public connection operates as an umbrella term for any orientation or practice by means of which individuals relate themselves to “what lies beyond [their] private worlds” (Swart et al., 2017b, p. 906; Couldry & Markham, 2008). As such, it allows for the inclusion of orientations and practices that are not explicitly based on media, e.g., face-to-face conversations about political issues; and it includes more specific concepts of communicative practices, for example, “reception” (Livingstone & Das, 2009), “produsage” (Bruns & Schmidt, 2011), “engagement” (Dahlgren 2009), and “participation” (Carpentier, 2011). In our understanding, public connection includes all orientations and practices through which an individual relates to some kind of public, i.e., a social entity that exists beyond the individual’s private world. To operationalize this concept for empirical research, we need to specify it in two steps.

Connection to multiple publics

A key argument of our approach is that individuals connect to different publics in their everyday lives (Couldry et al., 2007; Ytre-Arne & Moe, 2018). For instance, individuals may connect to the polity publics of their home country, and/or the more localized public of their hometown, to an interest group dedicated to a specific topic, and/or to a group of people who share a particular aspect of identity. From this individual-centered perspective, an individual’s public connection is a structured pattern of connections to different publics. Therefore, by adapting the repertoire-oriented approach to patterns of media use (Hasebrink & Popp, 2006), we conceptualize individuals’ patterns of connection to publics as their “public connection repertoire.” This approach is characterized by three key principles (Hasebrink & Domeyer, 2012). Firstly, it takes an individual-centered perspective; rather than taking a public-centered perspective that asks which individuals a particular public includes, this concept emphasizes the question to which publics a particular person connects. Secondly, the approach stresses the need to consider the whole variety of publics to which a person connects. And thirdly, it stresses the relationality among these publics; within the repertoire-oriented approach, the interrelations, and specific functions of the components of a public connection repertoire are of particular interest since they represent the inner structure or coherence of the repertoire. Taken together, these principles allow for a holistic view of an individuals’ public connection as a structured pattern of references to different publics.

Regarding empirical studies of public connection repertoires, this approach requires collecting data on all or at least the most relevant publics in which the individual is involved. Qualitative interviews are very well suited to obtain a comprehensive overview of relevant publics and to capture an individual's understanding of publics in general. Presenting participants with the three types of publics as presented above helps to elicit individuals’ responses on the overall concept and their repertoire of relevant publics. While this kind of procedure provides detailed information that reflects individuals’ everyday life, the drawback might be the high variance of relevant publics and the challenge to aggregate the findings across individuals. Therefore, in a recent pilot study we combined qualitative interviews which gave insight into the variety of potential publics with a standardized survey to capture how connections to relevant publics are distributed among the population. In the survey, we asked all respondents to report on their connection to the public of the city or region where they live, to the national public, to their most relevant topic public, and to their most relevant group public. To reduce the number of highly specific topic and group publics, we classified them into a number of broader topic areas (e.g., politics, sports, culture, etc.) and of group categories (e.g., gender, migration, religion, etc.). After this first step of identifying relevant publics, to which individuals connect themselves, we need to specify the concept of public connection itself.

Levels of public connection

As outlined in the previous paragraph, public connection repertoires are structured along the particular publics in which the individuals are involved in. For a more elaborate description of these repertoires, we need to specify what it means to be involved in a public. To operationalize the concept of public connection for empirical research, we conceptualize an individual’s connection to a particular public as a relationship that can be described on four basic conceptual levels that have been established in psychology (McGrew, 2022): the affective, cognitive, motivational, and conative level.

At the affective level, individuals experience a stronger or weaker sense of belonging to a public (Anthias, 2008), they “feel connected” with the other members of this public, and the public matters to them (Lünenborg, 2020). While the strength of the relation between the individual and the respective public is the most important aspect for the empirical assessment of an affective connection, there might be nuances of emotional orientations, e.g., harmonious, or conflict-laden, sentimental or prosaic.

At the cognitive level, individuals have certain perceptions of the public and their position in it. They know about relevant actors in this public and their respective roles, about frames of relevance that characterize the public, and about communicative practices that constitute this public. Prominent examples of individuals’ perceptions of a public are self-efficacy regarding their own role in a public (Caprara et al., 2009) and the perceived duty to keep informed regarding normative expectations in the respective public (McCombs & Poindexter, 1983).

At the motivational level, individuals are more or less interested in information about the public and in actively participating in the construction of the public. Key indicators for this level are interest in news (Fletcher & Nielsen, 2018) and interest in politics (Bimber et al., 2015). At this level, also the various gratifications-sought as analyzed in uses-and-gratifications research (Ruggiero, 2000) can be used as indicators for individuals’ motivation to connect to a particular public.

At the conative, action-oriented level, individuals use specific media that help to establish and to maintain the connection to certain publics on the informative and communicative level; thus, these media represent relevant parts of individuals’ media repertoires (Hasebrink & Hepp, 2017). Furthermore, they participate in other activities that constitute the respective public, for instance, elections, assemblies, or demonstrations. Thus, as indicated above, this level refers to the range of actions that have been defined and investigated as “media usage” in the narrow sense (Hasebrink & Domeyer, 2012) and as “participation” (Boulianne, 2015; Carpentier, 2011) in the broader sense.

Indicators for public connections on these four levels are obviously correlated. People who have a strong sense of belonging to a certain public tend to know more about this public, to be more interested in it, and to be more engaged in practices related to this public. However, as many studies show, these indicators are not fully correlated. There are people who feel strongly attached to their respective polity public, but do not actively participate in public-related activities, e.g., voting (Knight Foundation, 2020). Others are very interested in receiving information about this public and in participating in its activities without feeling a strong sense of belonging. Thus, we do not regard the connection to a certain public as a one-dimensional phenomenon between a very weak and a very strong connection. Instead, we consider different qualities of connection that are characterized by a specific combination of affective, cognitive, motivational, and action-related aspects.

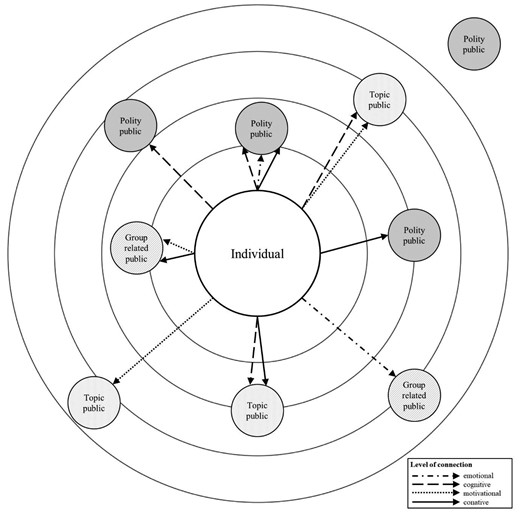

Figure 2 presents an illustration of a public connection repertoire. The visual design refers to the method we have been using to collect empirical data about media repertoires (Hasebrink & Domeyer, 2012; Merten, 2020); similar to ego-centered network maps, we ask respondents to name relevant components of their repertoire, in this case, the polity, topic, and group publics that are relevant to them. They then position these publics on a map of concentric circles, with the most relevant publics very close to the center, and the less relevant publics at the periphery. Furthermore, through different kinds of interview techniques we collect data on the level of connection to these publics. As a result, we get maps as illustrated in Figure 2, showing the relevant publics and the level of connection to them.

As indicated above, this empirical approach is based on methods of qualitative interviewing. Thus, it is particularly helpful for investigating public connection repertoires from the individuals’ perspective: It provides information on what publics individuals themselves regard as relevant. Beyond that, the proposed conceptual framework allows for other kinds of empirical approaches. For instance, if the research interest focuses on the respondents’ connection to a pre-defined set of publics, public connection repertoires can be investigated by means of standardized surveys. Furthermore, it is possible to reconstruct public connection repertoires through the analysis of digital traces with regard to individuals’ connections to specific actors, organizations, and networks (Christner et al., 2021; de Vreese & Neijens, 2016; Merten et al., 2022a; Prior, 2009). A measurement of digital traces could complement self-reported data in our current media environment shaped by incidental and ubiquitous exposure that makes self-reported media use less reliable (Parry et al. 2021, Stier et al. 2020). Especially retrospective data donations from individual users that combine mobile and desktop web browsing data and/or data takeouts from various social media platforms and/or search engines have the potential to capture digital public connection repertoires more comprehensively (Merten, forthcoming; Araujo et al., 2022).

In this respect, the conceptual framework offers an analytical perspective on the whole range of public communication, including practices in fluid digital network publics that might be hard to investigate through direct questions or other self-reported data.

To sum up, we conceptualize public connection repertoires as a structured pattern of different kinds of relationships to a set of publics. These public connection repertoires can be used in two ways. At the individual level we analyze which publics an individual connects to through what kinds of affective, cognitive, motivational, and conative characteristics. These descriptions are interpreted, for instance, against the background of the individual’s social position and personal values. On this basis, it is possible to identify types of individuals with similar public connection repertoires. On the level of publics, and across different individuals, our approach allows for an empirical analysis of the communicative figuration of specific publics as the following section will demonstrate.

Analyzing the communicative figurations of publics

In order to meet the core objective of our approach, i.e., to examine how individuals contribute to the construction of the publics in which they are involved, the final step of our conceptual approach integrates the two levels that have been discussed in the previous sections, the level of publics, and the level of individuals: Communicative figurations of publics can be described by the social characteristics and public connection repertoires of those individuals who are involved in these publics. At the same time, in line with Elias’ dynamic and interactive understanding of figurations, individuals’ public connection repertoires can be described by the publics, to which they connect themselves (see Figure 3).

Communicative figuration of publics as constituted by individuals’ public connection repertoires.

Starting from empirical observations on the individual level as outlined in the previous section, one analytical strategy is to focus on one specific public as illustrated in Figure 3. The actor constellation of a specific public includes all individuals who are connected to this public; its frame of relevance is characterized by the meanings that these individuals attribute to this public within their public connection repertoire; and it is constructed by the respective practices that these individuals apply to connect to this public. Furthermore, regarding the actor constellation we can ask whether the social background of the individuals who connect to this public is rather homogeneous, or rather diverse. Regarding the frame of relevance, the public connection repertoires provide evidence of the degree of consensus or conflict within the figuration. And with regard to the communicative practices, we can analyze the contribution of specific media to the construction of this public. Answers to these questions are highly relevant for discussions, e.g., on the fragmentation of societies, on social cohesion within different publics, and on the role of different types of media for public communication. And they can be interpreted from the perspective of different democratic theories with their specific normative expectations towards individual citizens.

Another analytical strategy goes beyond single publics and examines the relationships between different publics. To what extent do their actor constellations overlap? What are commonalities and differences concerning the respective frames of relevance and communicative practices? Observations on the interplay of different publics can help us to get deeper insights into the “general public” that we regard as the overall figuration of single publics’ figurations.

Conclusion

What are the implications of the proposed conceptual approach for the empirical analysis of individuals’ contribution to the construction of publics?

This approach can help to strengthen empirical research on (transformations of) publics. We conceptualize publics as social domains that can be analyzed as communicative figurations constituted by an actor constellation, frames of relevance, and communicative practices. Our approach offers a general heuristic that can be applied to a wide range of research designs. Empirical observations along this framework can be used for comparative—across different publics—and longitudinal—within a certain public—analyses. This will complement rather normative conceptualizations of public spheres and contribute to a more fruitful interplay between theory and empirical observations. This advantage is linked with an important limitation of our approach: It does not explain the constitution of a certain public or the ongoing changes of publics, nor does it offer normative criteria for the functioning of publics; it provides just a conceptual tool to describe publics and their transformation. Thus, specific studies on individuals’ contribution to publics need to contextualize their observations by linking them to more specific theoretical models and frameworks. For instance, empirical data on the communicative practices that constitute the figuration of a public should be interpreted in the light of different theoretical models of democracy as more or less consistent with the liberal, participatory, or deliberative model. Findings with regard to the homogeneity or heterogeneity of single publics and to overlaps between different publics should be discussed against the background of theoretical work on social cohesion and fragmentation.

Our approach allows for a more appropriate understanding of individual citizens as one type of actor that is involved in the construction of publics. This focus on individuals is due to the observation that: (a) there is a particular lack of theoretical and empirical work on these non-professional actors; and (b) recent developments towards a more digital media environment affect the role of individual media users in a substantial way. To analyze individual citizens’ contribution to publics we have proposed to identify their public connection repertoire, i.e., the structured pattern of relations to different publics. Our emphasis on individuals as actors does not imply that other actors that belong to the actor constellation of publics, are less important. On the contrary, the figurational approach provides a conceptual framework for analyzing the entire actor constellation, including individual citizens.

With our approach, we put a strong emphasis on the fact that individual citizens usually connect to more than one public. This has several important implications. The observation that an individual is not connected to a specific public, e.g., the national public, does not necessarily mean that this individual is completely disconnected from the public world; he or she might be closely connected to other publics, for instance, the local public or specific topic or group publics. Furthermore, from our perspective, the existence of manifold publics in a society does not necessarily mean that this society is fragmented or lacks cohesion. Individuals’ connections to many publics lead to overlaps of different publics’ actor constellations and consequently overlaps in frames of relevance, communicative practices but also issues addressed within these publics. The figurational approach allows for analyzing these overlaps and their implications for the functioning of different publics.

In our view, while the general concept of the public sphere has proven fruitful to stimulate debates and research on the communicative aspects of societies, evidence-based analyses of the communicative figurations of publics that include all actors involved in these publics are an indispensable prerequisite for understanding current transformations of public communication and of societies as a whole.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Funding

This research has been funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – no. 413631218. The authors thank the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this manuscript.