-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Felipe C Cabello, Henry P Godfrey, Microbiology, Public Health, and the Murals of Diego Rivera, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 78, Issue 6, 15 June 2024, Pages 1662–1668, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad715

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Diego Rivera, an acclaimed Mexican painter active during the first half of the 20th century, painted multiple frescoes in Mexico and the United States. Some include depictions of bacteria, their interactions with human hosts, and processes related to microbiology and public health, including the microbial origin of life, diagnosis of infection, vaccine production, and immunization. Microbiological subjects in Rivera's murals at the Mexican Ministry of Health in Mexico City; the Detroit Institute of Art, Detroit; Rockefeller Center, New York/Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City; Chapultepec Park, Mexico City; and the Institute of Social Security, Mexico City, span almost 25 years, from 1929 to 1953. Illustrating the successes of the application of microbiological discoveries and methods to public health and the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases, they benefited from Rivera's creativity in melding microbiology's unique technological and scientific aspects and public health elements with industrial and political components.

“His culture and his talent peculiarly fit him for the task of converting into elements of plastic beauty the cold motifs of science.” —Ignacio Chávez, Founder and Director of the Mexican National Institute of Cardiology, and Founding Member, Mexican National Academy of Arts and Sciences, on Diego Rivera [1]

The practice of public health involves a multiplicity of disciplines [2]. The continuing relevance of relationships between the visual arts and science is clearly illustrated by the worldwide distribution of images of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [3]. While there is undoubtably still tension between the role and relevance of art and the sciences to human and societal development, there is also tension regarding their ability to foster appropriate responses to the increasingly common challenges encountered by humanity [4, 5]. Albert Edelfelt's emblematic 1885 oil painting of Louis Pasteur at work at his laboratory bench is still a widely accepted and imitated example of the synergy between art and the sciences in general and microbiology in particular [6].

Diego Rivera took a different approach to art and microbiology. He, together with his fellow Mexican artists, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros, revived painting directly on plaster, Buon Fresco, a technique that had fallen out of favor by the 17th century. Using this technique, Rivera created monumental paintings on the walls of public buildings, which both beautified them and educated their viewers. In 5 of his many murals, he extended his gifted representations of macroscopic and microscopic subjects to microbiological topics [7, 8]. Because awareness of these themes in Rivera's murals is not widespread, particularly in the English-speaking world, they are the focus of this review.

MINISTRY OF HEALTH, MEXICO CITY (1929–1930)

Rivera's first frescoes with microbiological content are a large mural on the walls and ceilings of the boardroom of the Ministry of Health, 2 smaller ones on the walls of the hall leading to a clinical infectious diseases laboratory on the same floor, and 4 stained-glass windows of the 4 elements (earth, fire, air, water) on another floor [8–13].

The monumental female nudes on the boardroom walls represent different aspects of health: Fortitude, Wisdom (Knowledge/Science), Temperance (Continence), Purity, Life, and Health. Three of the large nudes, Wisdom, Temperance, and Health, can be considered related to the microbiological sciences, since science and the knowledge of microbiology are necessary for preventing infectious diseases, while, in an epoch lacking effective antimicrobials, Temperance and Purity are critical for preventing sexually transmitted diseases. This is reminiscent of Rivera's first governmental commission, Creation, in the Simón Bolívar Amphitheater in Mexico City (1922–1923), where 1 of the 7 monumental female figures, Knowledge, is teaching a group of students, while another, Science, looks down on them from above [8–10].

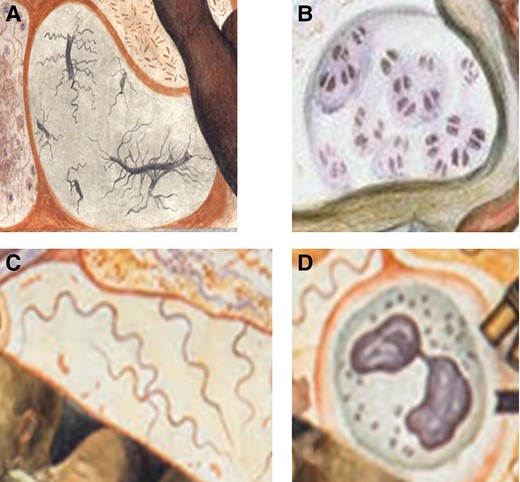

The 2 smaller panels in the hall leading from the boardroom to the clinical laboratory (cataloged as Microbial Flora) depict microscope views of bacteria stained with various dyes (Figure 1). Both panels are framed by cupped dark hands, visually underscoring Mexico's racially mixed population and the ability and necessity of all ethnic groups to keep these microbes under control to prevent their causing disease. The first (labeled “Education and Prophylaxis” to the left, “Public Health” to the right) (Figure 1A) shows 11 microscope fields with bacteria stained with various stains: streptococci, diplococci (presumably pneumococci), gram-negative bacilli, vibrios, flagellated bacilli (presumably Salmonella Typhi) (Figure 1A, arrowhead; Figure 2A), and spirochetes. The second (labeled “Hygiene” to the left, “Microbiology” to the right) (Figure 1B), shows 8 microscope fields with gram-positive and -negative cocci, bacilli, and spirochetes. All the bacteria and their stains are readily recognizable from images in contemporaneous texts [14, 15], and extend the fidelity noted in Rivera's macroscopic and microscopic anatomical representations in other murals [16–18]. These images provide a clear educational message that knowledge and mastery of the sciences dealing with bacteria, the diseases produced by them and their control, together with the 4 elements are critical to the preservation of life and health represented by the female nudes.

Microbial Flora (fresco), Ministry of Health, Mexico City. A, “Education and Prophylaxis” (left), “Public Health” (right). The arrowhead points to potential Salmonella Typhi (see also Figure 2A). B, “Hygiene” (left), “Microbiology” (right). The arrowhead points to gram-positive diplococci within phagocytes. In both panels, some bacteria are free in the tissues; others are associated with or within phagocytes (B, arrowhead). Image was provided by ©Bob Schalkwijk. Reproduced with permission from Banco Mexico Diego Rivera Trust, Mexico, DF/Artists Rights Society, New York.

Some bacteria depicted in Rivera's frescoes. A, Salmonella Typhi. Detail from Figure 1A, Microbial Flora, Ministry of Health, Mexico City. B, Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Detail from Figure 3A, Detroit Industry, Detroit Institute of Art, Detroit. C, Treponema pallidum. Detail from Figure 4, Man, Controller of the Universe, Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City. D, Polymorphonuclear leukocyte with intracellular cocci, perhaps Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pneumoniae. Detail from Figure 4, Man, Controller of the Universe, Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City. Reproduced with permission of Banco Mexico Diego Rivera Trust, Mexico, DF/Artists Rights Society, New York.

DETROIT INSTITUTE OF ART, DETROIT (1932–1933)

The Detroit Institute of Art, with the support of Edsel Ford and his family, commissioned Rivera to decorate the museum's Garden Court [8–10, 18–20]. The resulting 27 murals, entitled Detroit Industry, examine automotive, aeronautical, and pharmaceutical elements of Detroit's industry at the time.

The large murals portray activities directly related to heavy industry. Some of the small murals focus on the microbiological sciences, medicine, the pharmaceutical industry, and vaccine production. These complement Rivera's ideas of a continuum from inanimate matter to living organisms [19]. In 1 small panel (Healthy Human Embryo), bacteria stained using various microbiological techniques surround an embryo (Figure 3A). The etiologic agents of syphilis, perhaps gonorrhea (Figure 3A, arrowhead; Figure 2B), diphtheria, cholera, and anthrax are recognizable, sending a clear message that science and microbiology are necessary to avoid infection of healthy people of all ages [8–10, 19–21].

![Detail from Detroit Industry (fresco), Detroit Institute of Art, Detroit. A, Healthy Human Embryo. Presumed etiologic agents of typhoid, diphtheria, cholera, and anthrax surround an embryo and are easily recognizable. The arrowhead points to potential Neisseria gonorrhoeae (see also Figure 2B). B, Vaccination. The fresco is painted in the manner of a Renaissance Nativity. While some have identified the scientists in this mural as Pasteur, Koch, and Metchnikoff, they do not resemble the most common images of these early scientists and are perhaps an idealization of them. Others believe the 3 scientists represent the 3 Magi from a modern Nativity [9, 19–21]. The image in panel A is from Bridgeman Images, New York/Detroit Institute of Art; the image in panel B is from Detroit Institute of Art. Both images reproduced with permission of Banco Mexico Diego Rivera Trust, Mexico, DF/Artists Rights Society, New York.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/cid/78/6/10.1093_cid_ciad715/1/m_ciad715f3.jpeg?Expires=1750188388&Signature=pIvhS7EgYqDxbyTc8RigMvSRBQdysfW9zNAHlBAZ8EDDaC85Nusyx~9TKhw1-bqmeeUODSVxX7g0~l9WzZrsnHnvePgoezzACL88eYZIU1R3na~RNySvX1QE7aPq8jrNbkYV96i19qCPPHyKafcclthG3SSIO-9EfgnaVyFWTbVmAKcN~hhUspPqDO66QwDm4oXyq2iz7GBhTecVd2ww2doV39ztgSmoEDjyOMKIjgLlDoNthLwiN3qoBJ~8Znmf3LLHTaWcFasNeB6YtWGMBT0ghqsLCtBqOhUbYDWMf5cx6r8DIXAsP2nTGOBGL~0cjP5DhJgQFIIImceqKmwOjQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Detail from Detroit Industry (fresco), Detroit Institute of Art, Detroit. A, Healthy Human Embryo. Presumed etiologic agents of typhoid, diphtheria, cholera, and anthrax surround an embryo and are easily recognizable. The arrowhead points to potential Neisseria gonorrhoeae (see also Figure 2B). B, Vaccination. The fresco is painted in the manner of a Renaissance Nativity. While some have identified the scientists in this mural as Pasteur, Koch, and Metchnikoff, they do not resemble the most common images of these early scientists and are perhaps an idealization of them. Others believe the 3 scientists represent the 3 Magi from a modern Nativity [9, 19–21]. The image in panel A is from Bridgeman Images, New York/Detroit Institute of Art; the image in panel B is from Detroit Institute of Art. Both images reproduced with permission of Banco Mexico Diego Rivera Trust, Mexico, DF/Artists Rights Society, New York.

The Pharmaceutical Industry panel imparts a sense of the activities involved in the industrial production of vaccines and antisera, including the necessity of a large team of people focused on a common goal. Vaccination (Figure 3B) is more poignant. It recalls a Renaissance Nativity scene where the infant Jesus and the Virgin Mary have been replaced by a child to be vaccinated and a nurse holding him to expose his arm [8–10, 19–21]. This similarity is strengthened by the presence of a horse, several goats, and an ox in the lower part of the panel. Rivera was well aware of the use of such animals in research and in production of vaccines and antisera in his depiction of a microbiology laboratory at the rear of this scene. A dead animal (perhaps a rabbit) [19, 20] lies on a table, its body covered by a cloth, bound paws uncovered, while a scientist looks through a microscope behind it. A row of glass flasks stands in front of 2 more scientists. The linkage between experimental laboratory work and vaccine production is established by the vats needed for culturing the large volumes of bacteria required for manufacturing vaccines. Rivera's insertion of biological and medical themes in a work directed at portraying heavy industry might well be related to his ideas regarding the essentiality of workers’ health to their productivity, while offering contrasts and parallels between industries working with inanimate materials and industries dealing with life and its preservation [8, 9, 19–21].

ROCKEFELLER CENTER, NEW YORK/PALACIO DE BELLAS ARTES, MEXICO CITY (1933–1934)

Rivera restated his dynamic conception of relationships of microorganisms, hosts, and health in his provocative mural, Man at the Crossroads. It was commissioned by the Rockefeller family in 1933, painted at Rockefeller Center in New York City in 1934, and destroyed by them that same year because it contained portraits of Lenin and other communists as well as the implicit anticapitalistic tone of many of its pictorial elements [8, 9, 22–25]. Rivera subsequently replicated this mural later that year in Mexico City in a smaller format as Man, Controller of the Universe at the Palacio de Bellas Artes using sketches and black-and-white photographs made by him and his assistants (Ben Shahn was one) before its destruction (Figure 4) [10, 22, 23, 25].

Detail from Man, Controller of the Universe (fresco), Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, a smaller version of the destroyed Man at the Crossroads, Rockefeller Center, New York. The ellipse shows microscope fields of stained, potentially pathogenic bacteria. Arrowheads point to Treponema pallidum (left; see also Figure 2C) and polymorphonuclear leukocytes with intracellular cocci (right; see also Figure 2D). Note the anatomically complex representation of the human airways and digestive tract in the upper portion of the ellipse, with the epiglottis and trachea and some respiratory epithelia at one end and the mouth and esophagus at the other, all potential ports of bacterial entry. The lower end of the ellipse shows a microscope with 4 oculars and 3 objectives; there is also a darkfield image of trypanosomes swimming among red blood cells. Image was provided by ©Bob Schalkwijk. Reproduced with permission from Banco Mexico Diego Rivera Trust, Mexico, DF/Artists Rights Society, New York.

Two gigantic intercrossing ellipses surround a man, the Master of the Universe (Figure 4). Rivera said this mural represented humans controlling the universe with machines, science, and technology. Central to his artistic conception was that expertise on the macrocosm was obtainable through astronomy and telescopes, while control of the microcosm required microbiology, histology, and microscopes [9, 22, 23]. In the large ellipse representing microbiological sciences, a picture of a microscope with several objectives and oculars at its lower end passes behind the right shoulder of the man at the crossroads. The interior of the ellipse arising from this microscope has many fields containing potentially pathogenic bacilli and spirochetes. Some, such as Treponema pallidum (Figure 4, left arrowhead; Figure 2C), are located extracellularly in tissues; others, such as apparently pathogenic cocci (Figure 4, right arrowhead; Figure 2D) lie within phagocytic cells, much as in the earlier murals in Mexico City at the Ministry of Health [8, 9]. To the right of the microscope, a darkfield image of trypanosomes swimming among red blood cells seems to allude to the widespread occurrence of Chagas disease in the Americas. The upper part of this end of the ellipse shows an anatomically complex representation (human airways, digestive tract, epiglottis, and trachea with some respiratory epithelia at one end, mouth and esophagus at the other), probably signifying potential ports of entry of some of the bacteria [9, 24].

These details establish a reciprocal and dynamic interaction between bacteria and hosts, which can result either in beneficial commensalism or infection and disease. Rivera illustrates these interactions in the ellipse behind the man's lower left hip by histological sections of human tissues, especially of sexual ones, both as potential targets of these microorganisms and as generators of new life [22–25]. Just as knowledge and understanding of the macrocosm, nebulae, and planets requires the use of telescopes (as shown in the other ellipse in this mural), control of the universe by humans requires understanding of the microcosm, of beneficial and deleterious microorganisms and their interactions with the host, and the use of microscopes. Mastery of the world thus demands the use of all of the sciences and their instruments and techniques.

CHAPULTEPEC PARK, MEXICO CITY (1951)

Rivera's next fresco with specifically microbial themes is in Mexico City's Chapultepec Park. Carcamo del Lerma or Carcamo de Dolores was at the terminal of a 60-km underground aqueduct from the Lerma River supplying Mexico City's water system [8, 9, 26–28]. In addition to Water, Origin of Life (the submerged fresco in the water-distribution chamber of this building), Rivera also designed a recumbent outdoor statue of the Aztec water god, Tlaloc, whose hands were painted in the chamber over the end of the aqueduct bringing the water from the Lerma River.

The mural begins with 9 painted ribbons in the tunnel entering the floor of the distribution chamber under the hands of Tlaloc that depict individual cells and clumps of unicellular and multicellular aquatic microorganisms, including bacteria, protozoa, and diatoms [8, 9, 26–28]. The trained eye can recognize cyanobacteria, Entamoeba and Giardia, among the microorganisms [27, 28]. Unicellular and multicellular aquatic organisms are seen in the central circle in the floor of the chamber, the dark background probably showing darkfield microscopy (Figure 5). The biological complexity of the microorganisms increases as the ribbons widen into the floor of the chamber, with larger and larger aquatic animals (crustaceans, fishes, amphibians, reptiles) appearing as the ribbons ascend the vertical walls. This progression ends with male and female dark-skinned Mexican figures crowning the evolutionary ascent that begins under Tlaloc's hands [8, 9–12].

Detail from Water, Origin of Life (fresco), Carcamo del Lerma, Chapultepec Park, Mexico City (restored in 2010, now maintained as part of the Museo Nacional de Historia, Mexico City). Nine painted ribbons in the tunnel entering the floor of the distribution chamber under the hands of Tlaloc show individual cells and clumps of uni- and multicellular aquatic microorganisms, with the central dark circle probably representing uni- and multicellular organisms observed under darkfield microscopy. The biological complexity of the painted microorganisms increases as the ribbons widen on the floor of the chamber, suggesting an evolutionary progression that ends with figures of a man and a woman on the vertical walls, crowning the ascent that began with uni- and multicellular microorganisms. Image from Museo del Carcamo de Chapultepec, Mexico City. Reproduced with permission of Banco Mexico Diego Rivera Trust, Mexico, DF/Artists Rights Society, New York.

Rivera appears to have used a Spanish translation of Haeckel's Generelle Morphologie der Organismen (General Morphology of Organisms) published in Barcelona in 1885 as an inspiration for these drawings [29], a book in which Haeckel postulated that bacteria were the simplest form of life. Rivera also spent hours in a laboratory observing drops of water under the microscope [9], and his images are in agreement with theories (such as the Oparin-Haldane theory) that life, and specifically microbial life, originated in water, as well as with the tenets of evolutionary theory that suggest that evolution has proceeded from simple to complex forms of life [8, 9, 27–30]. Rivera is known to have met Oparin in 1954 during his second trip to the Soviet Union and even made a pencil sketch of him that hung in Oparin's apartment for many years [9, 27–29; A. Lazcano, personal communication, 2022]. It is not implausible to surmise that Rivera was aware of the Oparin-Haldane theory by his inclusion of jagged shapes in the darkfield image to signify bolts of energy, well before this theory received experimental support [29, 30]. In any case, the totality of Rivera's images clearly demonstrates his familiarity with biological ideas and theories current at the time he produced this work [8, 9, 19, 27–29].

NATIONAL MEDICAL CENTER LA RAZA, INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SECURITY, MEXICO CITY (1953)

Rivera's last mural with microbiological/public health elements, History of Medicine in Mexico: The People's Demand for Better Health (Figure 6) [8, 9, 11, 18, 31–33], presents a rich tableau of indigenous activities of pre-Columbian medicine in its right half and the activities of modern medicine in its left [34], separated by the Aztec/Méxica purification goddess, Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina. The healing and medical activities of pre-Columbian times are depicted in vivid colors and with great detail, with the richness of these activities in these times in striking contrast to those of modern medicine.

![Detail from History of Medicine in Mexico: The People's Demand for Better Health (fresco, mosaic, and multimedia), Medical Center de la Raza, Institute of Social Security, Mexico City, Mexico. The activities of modern medicine are shown in the left-hand segment of the fresco. The people in the images are readily identified as contemporaneous health workers, some of them microbiologists [33]. A, Near the central image of the Aztec purification deity, Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina, a health professional applies an intradermal tuberculin test to the forearms of 3 children. B, At the left lower left of the mural, a seated microbiologist and his standing assistant use an electron microscope. C, In the center of the mural, a little girl in a mauve dress with a withered left leg, presumably a result of polio, holds her pregnant mother's hand. Rivera was well aware of the ravages of polio, as his wife, Frida Kahlo, was affected by polio [33]. Images from Ms. Gabriela Rodríguez-Gómez. Reproduced with permission of Banco Mexico Diego Rivera Trust,Mexico, DF/Artists Rights Society, New York.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/cid/78/6/10.1093_cid_ciad715/1/m_ciad715f6.jpeg?Expires=1750188388&Signature=M5GX0MPWu66uou5vIHIoyCQpUvxzLje4kQH3hCeP9tLctO-bzFVl-5yr4Z1g7HVELTB9gHoqmSx8OGmOUl1ncB7oDytfeoAf91rpqWORxz4C7U25IfXCt0lV-AlsyB7oIlsdzJWZT1Xtm~80ZGDVQkQnZl0-zetuZkK5FUNNbrqhzLAKvk~1eDuIQr-YfbrOmq1sS6LZbgBiFuUKoKwvqhpXR1F0CuqXKbmQfw9qogyHufZbmtnmL9TyNSyqbwEyLvoJRDDaYf5SdCcifKuz7hOWSFVM8U9lZnwouNevrQ0mRkv-PaUf60AauoGrbzzZm2WvWAwEjcm2WAFLvR9NGg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Detail from History of Medicine in Mexico: The People's Demand for Better Health (fresco, mosaic, and multimedia), Medical Center de la Raza, Institute of Social Security, Mexico City, Mexico. The activities of modern medicine are shown in the left-hand segment of the fresco. The people in the images are readily identified as contemporaneous health workers, some of them microbiologists [33]. A, Near the central image of the Aztec purification deity, Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina, a health professional applies an intradermal tuberculin test to the forearms of 3 children. B, At the left lower left of the mural, a seated microbiologist and his standing assistant use an electron microscope. C, In the center of the mural, a little girl in a mauve dress with a withered left leg, presumably a result of polio, holds her pregnant mother's hand. Rivera was well aware of the ravages of polio, as his wife, Frida Kahlo, was affected by polio [33]. Images from Ms. Gabriela Rodríguez-Gómez. Reproduced with permission of Banco Mexico Diego Rivera Trust,Mexico, DF/Artists Rights Society, New York.

The focus of this latter section is the struggle of social groups to gain access to modern medical care and technologies from medical and political bureaucracies [9, 18, 33]. One group of images near the central image of the Aztec deity shows a modern health professional applying an intradermal tuberculin test to the forearms of 3 dark-skinned children (Figure 6A). A second, at the left lower left side of this panel, shows a seated microbiologist and his assistant using an electron microscope, cutting-edge science in 1953 (Figure 6B). The third, in the center, shows a little girl in a mauve dress with an atrophic left leg (presumably from polio) holding her pregnant mother's hand (Figure 6C). Rivera's clear interaction with hospital health personal may well underlie his familiarity with a wide range of microbiology methods (including the then latest) and their role in filling societal needs for healthcare.

ART, MICROBIOLOGY, AND PUBLIC HEALTH

What motivated Rivera's concern with microbiology, microbial diseases, and public health in his artistic efforts? His evident awareness of its importance in diagnosis and prevention of bacterial diseases in the context of epidemiology and public health is clear from examination of these murals. It could be that he was more influenced by and responsive to the intellectual and political currents of his times than were many of his peers and that he saw his paintings on microbiology and public health as an educational tool in support of the health policies of the Mexican state following the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) [35]. These coincided with the creation of national institutions to prevent, diagnose, and treat a wide range of infectious diseases and to improve public health.

Although the source of Rivera's knowledge is unknown, his artistic activity was contemporaneous with important advances in microbiology and the introduction of antimicrobials for the treatment of infectious diseases. The human embryo (Figure 3A) surrounded by gonococci (Figure 2B) and the presence of the spirochetes of syphilis (Figure 2C) in Man, Controller of the Universe (Figure 4), underline Rivera's awareness of the effects of these diseases on the health of people of all ages. Efforts to control tuberculosis by isolation in sanatoria and the use of Bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccine, and the application of vaccines to control smallpox, tetanus, pertussis, and diphtheria reached similarly high levels during his lifetime. Rivera's attunement to advances in microbiology is illustrated by images from darkfield microscopy and an electron microscope in his murals. His work coincided with the dissemination of the methods of modern medical microbiology and diagnosis of infectious diseases in Latin American countries and the first published texts on medical bacteriology in English by Zinsser, his collaborators, and others [36, 37]. Some of the microscopic images Rivera painted may have been inspired by these texts as a result of his socializing with the Mexican medical and scientific elites. For example, the flagellated rods he painted in 1929 at the Ministry of Health, Mexico City, are uncannily similar to an illustration in a bacteriological atlas published in 1927 showing Salmonella Typhi stained with Muir stain for flagella and a drawing in a contemporaneous Zinsser text (Figures 1A and 2A) [14, 15]. Many other of his bacterial depictions exhibit great similarity to pictures in Muir's atlas and Zinsser's text, indicating his familiarity with this type of bacterial representation. Rivera might well have become familiar with these images during his stay in the United States.

Rivera also interacted with medical elites as a result of the repeated medical and surgical treatments of his wife, Frida Kahlo. These elites included the internationally famous Mexican cardiologist, Ignacio Chávez, who provided him with the material for the design of another health-related mural, The History of Cardiology [1, 16, 18, 37]. Inclusion of microbiological themes in Rivera's art occurred during a period of widespread interest in microbiology among the general public. Sinclair Lewis’ Arrowsmith in 1925 (its central character is an ambitious and progressive microbiologist), Paul de Kruif's Microbe Hunters in 1926, and Hans Zinsser's Rats, Lice and History in 1935 were all best sellers that contributed to popular understanding of the critically relevant role of microbiology in public health and human progress [38], as well as sharing aspects of the social criticisms that Rivera portrayed in his treatment of these topics in his murals.

Rivera's insight, imagination, artistic originality, and self-taught knowledge of microbiology and methods of analysis enabled him to generate a striking visual art in content and form. His stimulating and innovative approach melded different aspects of microbiology with its relation to humans, including the role of microorganisms in health and disease and their more general role in life on earth. This enabled him to educate his viewers to the idea that mastery over microorganisms through microbiology and public health was essential to insuring the well-being of humanity through the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases. His introduction of microbiology and public health into his art was highly original and a drastic transformation to what was considered suitable subject matter in art. Although medical and public health activities had been depicted in painting and sculpture since the Renaissance, Rivera's novel blending of art, microbiology, public health, and politics with educational and historical contexts represents a groundbreaking part of a movement that influenced subsequent artists in Mexico, the United States, and worldwide [5, 24, 39–42]. With the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and increases in tuberculosis, polio, and sexually transmitted diseases, these interactions have dramatically come to the fore and underscore Rivera's relevance for today's world [21].

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Dr. Niria E. Leyva-Gutiérrez and Dr. James Oles for comments and suggestions regarding documental sources and high-quality figures; Dr. Stuart A. Newman and Dr. Daniel F. Peters for assistance with anatomical interpretations of Man at the Crossroads/Man, Controller of the Universe; Gabriela Rodríguez-Gómez, A.B.D., for original photographs of The People's Demand for Health used in Figure 6 and for insightful comments and suggestions; Dr. Kathryn O’Rourke for comments and suggestions; Dr. Mariana Benitez and Dr. Carlos Lopez for procuring documental sources in Mexico; and Mr. Jeff Karr, Center for the History of Microbiology/ASM Archives (CHOMA) for useful suggestions regarding the images in Muir's Atlas and Zinsser's textbook. They thank Bob Schalwijk for assistance in choosing the images used in Figures 1 and 4 and Bridgeman Images for choosing the image used in Figure 3A. They also thank Dr. Antonio Lazcano Araujo for information regarding the relationship between Diego Rivera and Prof. Alexander I. Oparin. They thank the New York Medical College Health Sciences Library for facilitating many interlibrary loans. F. C. C. thanks his parents who introduced him to Rivera's work at an early age.

References

Author notes

Potential conflicts of interest. H. P. G. reports a role as an unpaid member of the Board of Trustees for Sheldrake Environmental Center, Larchmont, New York. F. C. C. reports no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.