-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Alex Rivero, Megan Shaughnessy, Amanda Noska, An Unusual Case of Cellulitis in a Patient With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 78, Issue 3, 15 March 2024, Pages 797–799, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad717

Close - Share Icon Share

A 56-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) on mycophenolate sodium, prednisone, and hydroxychloroquine sulfate presented with a 1-week history of left posterior thigh pain and swelling. On admission, she was febrile (39.5°C) but otherwise hemodynamically stable. Examination of the posterior left thigh showed a large, erythematous, indurated plaque that was warm to the touch and tender to palpation (Figure 1).

Large indurated plaque with overlying erythema of the posterior left thigh.

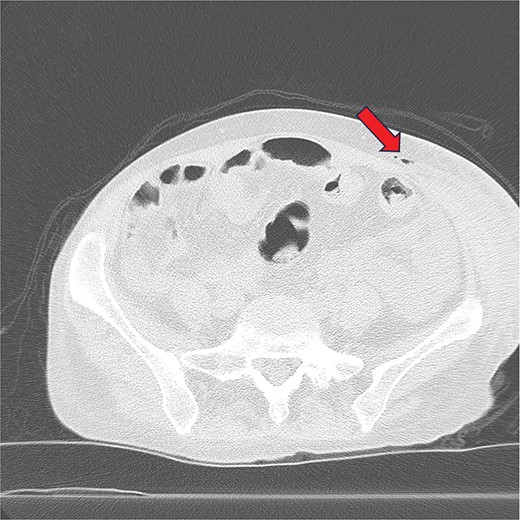

Laboratory results showed pancytopenia, including severe neutropenia, with an absolute neutrophil count of 0.18 k/cmm. She was started on vancomycin and cefepime for neutropenic fever and left lower extremity cellulitis. Computed tomography (CT) of the left lower extremity revealed infiltrative edema and skin thickening of the proximal thigh. CT also showed an incidental infiltrative fluid collection in the left lower quadrant abdominal wall with small foci of internal gas (Figure 2). She later confirmed new pain in this area as well.

Infiltrative fluid collection in the left lower quadrant abdominal wall with small foci of internal gas.

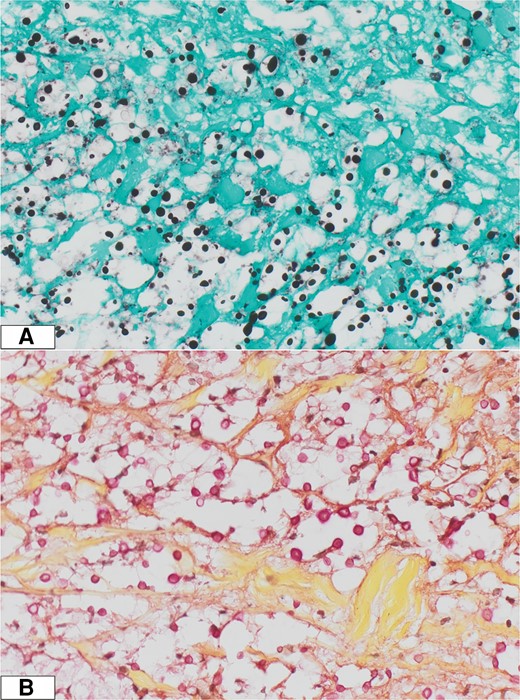

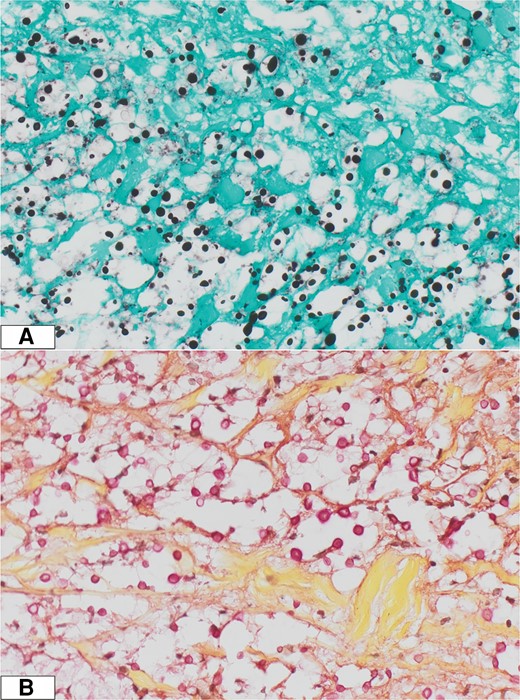

Surgery was consulted, and she underwent incision and drainage for management of a presumed necrotic skin/soft tissue infection of her abdominal wall. Intraoperative tissue and fluid were obtained for histopathology and microbiology evaluation. No necrosis was seen intraoperatively. A punch biopsy of the skin from the left posterior thigh was also obtained. The histopathology showed the implicated organism in Figure 3, and tissue cultures of both the abdominal wall and thigh confirmed the diagnosis.

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Cryptococcal cellulitis

Histopathology from the punch biopsy of the thigh showed deep fungal infection with budding yeast forms. Mucicarmine stain was consistent with Cryptococcus neoformans. Abdominal fluid and tissue cultures, fungal blood cultures, respiratory cultures, and bone marrow cultures ultimately grew Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii. Serum cryptococcal antigen was positive with a titer of >1:10 240. Fungal culture and cryptococcal antigen from cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) were negative. CSF opening pressure was 29 cmH2O, and the cell count was 1 cell/µL. Per current treatment guidelines for disseminated cryptococcosis and given the ongoing need for immunosuppression, we treated our patient with liposomal amphotericin B and flucytosine for 2 weeks, followed by fluconazole 400 mg daily for 8 weeks, and then 200 mg daily indefinitely. Mycophenolate was discontinued. She recovered well, and the skin lesions resolved by the time of hospital discharge.

The first descriptive publication regarding cryptococcosis dates back to 1894 by German pathologist Otto Busse [1]. Cryptococcus neoformans is found worldwide and is associated with bird excrement (particularly pigeons), soil, and plants. Transmission to humans usually occurs through environmental exposures via inhalation of yeasts or spores [2]. Spread to other organ systems, such as the central nervous system (CNS), bones and joints, and skin, can occur. Cutaneous manifestations occur in 10%–20% of patients with cryptococcosis. Although primary skin infection with Cryptococcus has been described, cutaneous involvement usually indicates a hematogenous source due to disseminated disease [3]. Cell-mediated immunity is the most crucial defense against Cryptococcus. Therefore, the greatest risk factor for infection is immunocompromise, such as human immunodeficiency virus, malignancy (particularly hematologic malignancy), and conditions such as SLE and solid organ transplant, where immunosuppressive medications are required [2]. In this case, we think our patient was susceptible to cryptococcosis due to both the bone marrow suppressive properties of SLE itself and the immunosuppressive medications required to manage SLE, leading to further cell-mediated immunopathogenesis.

Cutaneous findings of cryptococcosis may precede all other clinical manifestations of disseminated disease [4]. Although the classic skin findings include umbilicated and nodular lesions that resemble Molluscum contagiosum, there is no single specific finding of cutaneous disease. The literature describes many different findings, including cellulitis, ulcers, acneiform papules or pustules, plaques, nodules, subcutaneous swellings, vesicles, abscesses, solid tumors, ecchymoses, gummas, draining sinuses, and palpable purpura [2–6]. The lower extremities are the most common site of involvement in these cases, and contrary to bacterial infections, the presentation is often bilateral, reflecting disseminated disease and the involvement of other organs [4].

Given the wide range of skin findings, cutaneous cryptococcosis is frequently confused with other entities (eg, bacterial cellulitis, herpes zoster infection, endemic mycoses). Clinical diagnosis can be challenging and may lead to delays in starting appropriate treatment [6]. Confirmation of the diagnosis of cutaneous cryptococcosis is best achieved through histopathology and culture from a biopsy or an aspirate of a skin lesion [3]. Specialized stains such as Grocott's methenamine silver and Periodic acid-Schiff can be used to visualize the yeast, and mucicarmine stain will show the polysaccharide-rich capsule (Figure 4) [4]. Another helpful diagnostic test includes the cryptococcal antigen, which is highly suggestive of disseminated disease when present in serum or CSF [7].

A, Grocott's methenamine silver stain visualizing the yeast. B, Mucicarmine stain demonstrating the polysaccharide-rich capsule.

Treatment of disseminated cryptococcosis (ie, involvement of at least 2 noncontiguous sites) is similar to treatment of CNS disease. Current guidelines divide treatment into 3 phases: induction, consolidation, and maintenance. The induction phase consists of intravenous (IV) liposomal amphotericin B 3–4 mg/kg daily or IV amphotericin B lipid complex 5 mg/kg once daily plus flucytosine 100 mg/kg per day orally divided into 4 doses for a minimum of 2 weeks. Clinical improvement (and CSF sterilization if CNS involvement) should be achieved before transitioning to the next stage. The consolidation phase includes fluconazole 400 mg (6 mg/kg) per day orally for a minimum of 8 weeks. Maintenance therapy consists of fluconazole 200 mg per day orally for a minimum of 1 year [8]. In resource-rich settings, lipid amphotericin formulations are preferred, given favorable tolerability, decreased toxicity, and fewer treatment interruptions [9].

Untreated cryptococcosis is nearly 100% fatal. Despite improvement in access to proven medical therapies, the 3-month mortality rate during management of acute cryptococcal meningoencephalitis remains at 20% [8]. Management of complications, including persistent or relapsed infection, increased intracranial pressure, and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, is vital. Patients with persistent immunocompromise may require lifelong suppressive therapy.

This case shows that cryptococcosis can present in an atypical way. Cutaneous cryptococcosis is often confused with more common conditions (eg, bacterial cellulitis), which may delay diagnosis and treatment and increase the potential for severe consequences. Cryptococcosis should be included in the differential diagnosis in immunosuppressed patients with cellulitis, especially with a lack of response to initial antibiotic therapy.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We extend our sincere gratitude to Dr Bradley Linzie for his invaluable assistance in acquiring the histopathology images that have significantly enriched the content of this article. Additionally, we express our appreciation to Dr Gopal Punjabi for his expert guidance in selecting the abdominal computed tomography image featured in this article.

References

Author notes

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.