-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Christine M Khosropour, Olusegun O Soge, Matthew R Golden, James P Hughes, Lindley A Barbee, Incidence and Duration of Pharyngeal Chlamydia Among a Cohort of Men Who Have Sex With Men, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 75, Issue 5, 1 September 2022, Pages 875–881, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab1022

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The prevalence of pharyngeal chlamydia is low, but its incidence and duration are unknown. A high incidence or duration may support the role of pharyngeal chlamydia in sustaining chlamydia transmission.

From March 2016 to December 2018, we enrolled men who have sex with men (MSM) in a 48-week cohort study in Seattle, Washington. Participants self-collected pharyngeal specimens weekly. We tested specimens using nucleic acid amplification testing at the conclusion of the study. In primary analyses, we defined incident pharyngeal chlamydia as >2 consecutive weeks of a positive pharyngeal specimen. In sensitivity analyses, we defined incident chlamydia as >1 week of a positive specimen. We estimated duration of pharyngeal chlamydia, censoring at loss to follow-up, receipt of antibiotics, or end of study.

A total of 140 participants contributed 70.5 person-years (PY); 1.4% had pharyngeal chlamydia at enrollment. In primary analyses, there were 8 pharyngeal chlamydia cases among 6 MSM (incidence = 11.4 per 100 PY; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 6.0–21.9). In sensitivity analysis, there were 19 cases among 16 MSM (incidence = 27.1 per 100 PY; 95% CI: 18.5–39.8). The median duration was 6.0 weeks (95% CI: 2.0–undefined) in primary analysis and 2.0 weeks (95% CI: 1.1–6.0) in sensitivity analysis. Duration was shorter for those with a history of chlamydia compared with those without (3.6 vs 8.7 weeks; P = .02).

Pharyngeal chlamydia has a low incidence and duration relative to other extragenital sexually transmitted infections. Its contribution to population-level transmission remains unclear.

Prior to the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) infection was the most commonly reported infection in the United States. In 2019, there were 1.8 million reported cases of chlamydia, representing a 19% increase in the number of reported cases since 2015 [1]. CT infects cells in the urogenital tract, rectum, pharynx, and eye. CT control programs in the United States and globally have historically focused on reducing urogenital tract infections in an effort to reduce reproductive tract sequalae associated with CT infection. Over the past decade, there has been increasing emphasis on identifying and treating extragenital infections; however, most of the focus on extragenital chlamydia has been on rectal chlamydia [2]. Very little is known about the epidemiology, natural history, and clinical implications of pharyngeal chlamydia.

Most pharyngeal CT infections are asymptomatic, the infection is not known to be associated with significant morbidity, and routine screening for pharyngeal chlamydia is not recommended in the United States [2]. Despite this, at least among men who have sex with men (MSM), testing is commonplace since the nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) used to test patients for Neisseria gonorrhoeae include primers for C. trachomatis [2]. The prevalence of pharyngeal chlamydia among men and women is relatively low (about 1%–3%) [1, 3–5], and approximately 35%–50% of individuals spontaneously clear their infection in the time between screening and treatment [6–8].

The role of pharyngeal infection in population-level chlamydia transmission is uncertain. Empiric and modeling data suggest that pharyngeal chlamydia may be transmitted to genital sites [9–12], but the natural history of these infections, particularly the duration of untreated pharyngeal chlamydial infection, is ill defined. Our objective in this natural history study was to determine the incidence and duration of pharyngeal chlamydia among a cohort of MSM.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

All study data were collected as part of the ExGen Study, a 48-week, prospective, natural history study of extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydia. ExGen methods have been previously described and focused on pharyngeal gonorrhea and rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia [13, 14]. Briefly, between March 2016 and December 2018, we recruited MSM from the Public Health–Seattle & King County Sexual Health Clinic and the University of Washington’s Center for AIDS Research patient registry who met the following criteria: aged at least 18 years, English-speaking, had access to the internet, reported receptive anal sex in the past 12 months and performed oral sex in the past 2 months, and met at least 1 of the following eligibility criteria: had a diagnosis of gonorrhea, chlamydia, or syphilis in the past 12 months; reported using methamphetamine or amyl nitrate (ie, “poppers”) in the past 12 months; or reported having at least 2 sexual partners in the past 2 months or at least 5 sexual partners in the past 12 months.

Study Procedures

At enrollment (an in-person visit), consenting participants completed surveys that captured demographic, clinical, and sexual behavior data. Participants self-collected rectal and pharyngeal specimens for gonorrhea and chlamydia testing and were also tested for syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) if they were not known to have been previously diagnosed with HIV. Individuals who tested positive for a sexually transmitted infection (STI) at baseline were treated and asked to defer starting weekly study procedures until 2 weeks (for those who tested positive for gonorrhea) or 3 weeks (for those who tested positive for chlamydia) after treatment.

For 48 weeks following the enrollment visit, participants self-collected a pharyngeal and rectal specimen each week at home. Participants returned weekly specimens to the study team via mail (US Postal Service), and specimens were stored in a –80°C freezer until the participant completed their participation in the study. At the conclusion of an individual’s participation in the study, we tested all of their specimens using the Aptima Combo-2 NAAT (Hologic, Inc, San Diego, CA) on the fully automated Panther system [15]. At enrollment, study staff told research participants that their specimens would not be tested in real time and that participants should continue their usual STI screening practices. Each week, participants also received an email or text message with a link to a personalized, password-protected electronic survey hosted on the REDCap platform. The survey asked participants to report on the following activities since their last weekly survey: sexual behavior (eg, kissing, rimming, giving oral sex), symptoms (eg, sore throat), testing and treatment, and health and hygiene practices (eg, mouthwash use after sex). Participants received compensation for completing the surveys and for sending in their specimens. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study.

Definitions and Statistical Analyses

We defined incident pharyngeal chlamydia in 2 ways. In our primary analysis, we defined incident pharyngeal chlamydia as a participant having at least 2 consecutive weeks of a CT-positive pharyngeal specimen. In sensitivity analyses (less conservative definition), we defined incident pharyngeal chlamydia as a participant having at least 1 week of a CT-positive pharyngeal specimen. Thus, all infections included in the primary analysis were also included in secondary analysis. All analyses were completed using both the primary and sensitivity definitions of incident infection.

We defined clearance as having 2 consecutive weeks of a CT-negative pharyngeal specimen. If there were up to 2 consecutive negative, missing, or equivocal specimens that occurred between 2 positive specimens, we considered the negative, missing, or equivocal specimens to be positive.

We calculated incidence as the number of incident pharyngeal CT infections (using the definitions above) divided by time at risk. Weeks when individuals had positive pharyngeal CT test results were excluded from the denominator of time at risk. We calculated incidence as a rate per 100 person-years (PY).

We used Kaplan-Meier methods to examine time to pharyngeal chlamydia clearance and to estimate the median duration of pharyngeal CT infection. We calculated duration in days but describe duration in weeks for interpretability. We censored for 3 reasons: the participant was lost to follow-up; the participant received azithromycin or doxycycline (antibiotics active against CT) for any reason in the week of, the week prior to, or the week after a final positive week of infection; or the participant’s pharyngeal specimen was CT positive in the final week of the 48-week study period. We compared duration of pharyngeal chlamydia by history of CT infection (self-reported ever vs never and past 12 months but updated if participant tested CT positive at any anatomic site during the study and prior to the pharyngeal infection), HIV status (previously diagnosed with HIV vs not diagnosed with HIV), concurrent rectal CT infection (yes vs no; test results were from weekly rectal swab obtained as part of the study), and concurrent pharyngeal gonorrhea infection (yes vs no; test results were from the same pharyngeal swab as the pharyngeal chlamydia result). We used the exact log-rank test [16] to test for differences in duration distribution.

Additionally, in descriptive analyses, we examined the distribution of reported sexual behaviors and reported sore throat among participants with incident pharyngeal chlamydia.

All definitions and analyses are consistent with those used in this same population of MSM to estimate duration of pharyngeal gonorrhea, rectal gonorrhea, and rectal chlamydia [13, 14]. We used Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) for all analyses except the exact log-rank test, for which we used R v4.1.0 (coin package). Tests were performed at a significance level of 0.05.

RESULTS

We enrolled 140 MSM who collectively contributed 70.5 PY of follow-up, though 20% of participants did not send in any weekly specimens. Of the 112 men who sent in at least 1 weekly specimen, the median follow-up time was 39 weeks. The median age of participants was 35 years, 63% reported White race, and about half were living with HIV (Table 1). More than one-third had been diagnosed with chlamydia in the past year, and 68% reported ever being diagnosed with chlamydia. Characteristics of participants with at least 1 positive pharyngeal CT test during follow-up were similar to those of the overall study population (Table 1).

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Men Who Have Sex With Men Participating in a Natural History Study of Extragenital Gonorrhea and Chlamydia, 2016–2018 (N = 140)

| Characteristic . | All Participants (N = 140) . | Participants With >1 Positive Pharyngeal Chlamydia trachomatis Test During Follow-up (N = 16) . |

|---|---|---|

| . | N (%) . | N (%) . |

| Age, median (interquartile range) | 35 (28–46) | 38 (31–52) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White, not Hispanic/Latinx | 88 (62.9) | 13 (81.2) |

| Black, not Hispanic/Latinx | 15 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Asian, not Hispanic/Latinx | 8 (5.7) | 1 (6.3) |

| Other, not Hispanic/Latinx | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 25 (17.9) | 2 (12.5) |

| Previously diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus | 71 (50.7) | 7 (43.8) |

| Ever diagnosed with chlamydia | 95 (67.9) | 10 (62.5) |

| Diagnosed with chlamydia, past 12 months | 48 (34.3) | 6 (37.5) |

| Chlamydia diagnosis at enrollment | ||

| Pharyngeal | 2 (1.4) | 1 (6.3) |

| Rectal | 14 (10.0) | 2 (12.5) |

| Urethral | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Criteria for study entry | ||

| Bacterial sexually transmitted infection diagnosis, past 12 months | 104 (74.2) | 11 (68.8) |

| Methamphetamine or popper use, past 12 months | 35 (25.0) | 1 (6.3) |

| Number of sex partnersa | 117 (83.6) | 13 (81.3) |

| Characteristic . | All Participants (N = 140) . | Participants With >1 Positive Pharyngeal Chlamydia trachomatis Test During Follow-up (N = 16) . |

|---|---|---|

| . | N (%) . | N (%) . |

| Age, median (interquartile range) | 35 (28–46) | 38 (31–52) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White, not Hispanic/Latinx | 88 (62.9) | 13 (81.2) |

| Black, not Hispanic/Latinx | 15 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Asian, not Hispanic/Latinx | 8 (5.7) | 1 (6.3) |

| Other, not Hispanic/Latinx | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 25 (17.9) | 2 (12.5) |

| Previously diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus | 71 (50.7) | 7 (43.8) |

| Ever diagnosed with chlamydia | 95 (67.9) | 10 (62.5) |

| Diagnosed with chlamydia, past 12 months | 48 (34.3) | 6 (37.5) |

| Chlamydia diagnosis at enrollment | ||

| Pharyngeal | 2 (1.4) | 1 (6.3) |

| Rectal | 14 (10.0) | 2 (12.5) |

| Urethral | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Criteria for study entry | ||

| Bacterial sexually transmitted infection diagnosis, past 12 months | 104 (74.2) | 11 (68.8) |

| Methamphetamine or popper use, past 12 months | 35 (25.0) | 1 (6.3) |

| Number of sex partnersa | 117 (83.6) | 13 (81.3) |

Reported as at least 2 sex partners in the past 2 months or at least 5 sex partners in the past 12 months.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Men Who Have Sex With Men Participating in a Natural History Study of Extragenital Gonorrhea and Chlamydia, 2016–2018 (N = 140)

| Characteristic . | All Participants (N = 140) . | Participants With >1 Positive Pharyngeal Chlamydia trachomatis Test During Follow-up (N = 16) . |

|---|---|---|

| . | N (%) . | N (%) . |

| Age, median (interquartile range) | 35 (28–46) | 38 (31–52) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White, not Hispanic/Latinx | 88 (62.9) | 13 (81.2) |

| Black, not Hispanic/Latinx | 15 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Asian, not Hispanic/Latinx | 8 (5.7) | 1 (6.3) |

| Other, not Hispanic/Latinx | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 25 (17.9) | 2 (12.5) |

| Previously diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus | 71 (50.7) | 7 (43.8) |

| Ever diagnosed with chlamydia | 95 (67.9) | 10 (62.5) |

| Diagnosed with chlamydia, past 12 months | 48 (34.3) | 6 (37.5) |

| Chlamydia diagnosis at enrollment | ||

| Pharyngeal | 2 (1.4) | 1 (6.3) |

| Rectal | 14 (10.0) | 2 (12.5) |

| Urethral | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Criteria for study entry | ||

| Bacterial sexually transmitted infection diagnosis, past 12 months | 104 (74.2) | 11 (68.8) |

| Methamphetamine or popper use, past 12 months | 35 (25.0) | 1 (6.3) |

| Number of sex partnersa | 117 (83.6) | 13 (81.3) |

| Characteristic . | All Participants (N = 140) . | Participants With >1 Positive Pharyngeal Chlamydia trachomatis Test During Follow-up (N = 16) . |

|---|---|---|

| . | N (%) . | N (%) . |

| Age, median (interquartile range) | 35 (28–46) | 38 (31–52) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White, not Hispanic/Latinx | 88 (62.9) | 13 (81.2) |

| Black, not Hispanic/Latinx | 15 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Asian, not Hispanic/Latinx | 8 (5.7) | 1 (6.3) |

| Other, not Hispanic/Latinx | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 25 (17.9) | 2 (12.5) |

| Previously diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus | 71 (50.7) | 7 (43.8) |

| Ever diagnosed with chlamydia | 95 (67.9) | 10 (62.5) |

| Diagnosed with chlamydia, past 12 months | 48 (34.3) | 6 (37.5) |

| Chlamydia diagnosis at enrollment | ||

| Pharyngeal | 2 (1.4) | 1 (6.3) |

| Rectal | 14 (10.0) | 2 (12.5) |

| Urethral | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Criteria for study entry | ||

| Bacterial sexually transmitted infection diagnosis, past 12 months | 104 (74.2) | 11 (68.8) |

| Methamphetamine or popper use, past 12 months | 35 (25.0) | 1 (6.3) |

| Number of sex partnersa | 117 (83.6) | 13 (81.3) |

Reported as at least 2 sex partners in the past 2 months or at least 5 sex partners in the past 12 months.

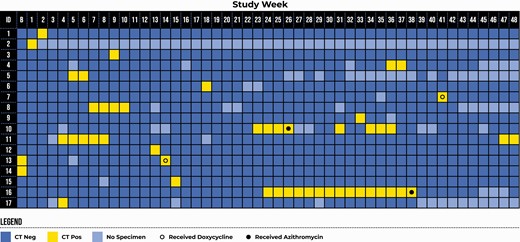

Figure 1 displays the weekly pharyngeal chlamydia test results for individuals who had at least 1 CT-positive pharyngeal specimen at enrollment or during follow-up. The prevalence of pharyngeal chlamydia at enrollment was 1.4% (2 of 140). Sixteen (11.4%) of 140 individuals had at least 1 positive pharyngeal chlamydia test during follow-up (after enrollment). Using the primary definition of incident pharyngeal chlamydia, there were 8 pharyngeal chlamydia infections among 6 MSM, for an incidence rate of 11.4 per 100 PY (95% confidence interval [CI]: 6.0–21.9). In our sensitivity analysis, there were 19 pharyngeal chlamydia infections among 16 MSM, for an incidence rate of 27.1 per 100 PY (95% CI: 18.5–39.8).

Weekly pharyngeal chlamydia test result for participants who had at least 1 week of a positive pharyngeal chlamydia test at baseline or during the 48-week follow-up period. Participants 13 and 14 waited 3 weeks prior to initiating study procedures because they were CT-positive at baseline. Abbreviations: B, baseline; CT, Chlamydia trachomatis.

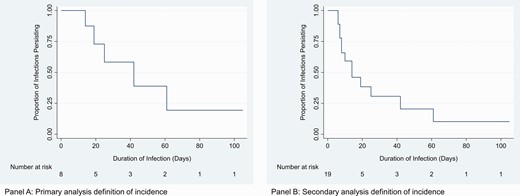

In primary analysis, the median duration of pharyngeal chlamydia was 6.0 weeks (95% CI: 2.0 weeks–undefined; Figure 2A). Three of 8 infections were censored, 1 for end of study and 2 for use of antibiotics. The 2 cases censored at time of treatment included 1 man who had been infected for 4 weeks and 1 who had been infected for 15 weeks. Of note, case 10, who was treated after 4 weeks, had 4 subsequent positive test results, including a series of 3 consecutive positive results occurring 8 weeks after receipt of azithromycin. In sensitivity analysis, the median duration was 2.0 weeks (95% CI: 1.1–6.0 weeks), with 6 of 19 infections censored (1 for end of study, 1 for loss to follow-up, and 4 for use of antibiotics; Figure 2B). The median duration of infection was shorter for individuals with a history of chlamydia compared with those without a history of chlamydia and in secondary analysis was shorter for individuals with concurrent rectal CT (Table 2).

| . | Primary Analysis . | Sensitivity Analysis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | n (N = 8) . | Median Duration, Weeks . | P Valuea . | n (N = 19) . | Median Duration, Weeks . | P Valuea . |

| History of CT (ever) | ||||||

| Yes | 5 | 3.6 | .02 | 13 | 2.0 | .12 |

| No | 3 | 8.7 | 6 | 8.7 | ||

| History of CT (past 12 months) | ||||||

| Yes | 5 | 3.6 | .02 | 9 | 2.0 | .82 |

| No | 3 | 8.7 | 10 | 1.1 | ||

| Concurrent rectal CT | ||||||

| Yes | 5 | 6.0 | .33 | 7 | 6.0 | .03 |

| No | 3 | 3.6 | 12 | 1.1 | ||

| HIV status | ||||||

| Living with HIV | 1 | 2.0 | .25 | 7 | 1.1 | .09 |

| Not living with HIV | 7 | 6.0 | 12 | 3.6 | ||

| Concurrent pharyngeal gonorrhea | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | 6.0 | .88 | 5 | 3.6 | .34 |

| No | 5 | 8.7 | 14 | 2.0 | ||

| . | Primary Analysis . | Sensitivity Analysis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | n (N = 8) . | Median Duration, Weeks . | P Valuea . | n (N = 19) . | Median Duration, Weeks . | P Valuea . |

| History of CT (ever) | ||||||

| Yes | 5 | 3.6 | .02 | 13 | 2.0 | .12 |

| No | 3 | 8.7 | 6 | 8.7 | ||

| History of CT (past 12 months) | ||||||

| Yes | 5 | 3.6 | .02 | 9 | 2.0 | .82 |

| No | 3 | 8.7 | 10 | 1.1 | ||

| Concurrent rectal CT | ||||||

| Yes | 5 | 6.0 | .33 | 7 | 6.0 | .03 |

| No | 3 | 3.6 | 12 | 1.1 | ||

| HIV status | ||||||

| Living with HIV | 1 | 2.0 | .25 | 7 | 1.1 | .09 |

| Not living with HIV | 7 | 6.0 | 12 | 3.6 | ||

| Concurrent pharyngeal gonorrhea | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | 6.0 | .88 | 5 | 3.6 | .34 |

| No | 5 | 8.7 | 14 | 2.0 | ||

Abbreviation: CT, Chlamydia trachomatis; HIV, with human immunodeficiency virus.

P value from exact log-rank test.

| . | Primary Analysis . | Sensitivity Analysis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | n (N = 8) . | Median Duration, Weeks . | P Valuea . | n (N = 19) . | Median Duration, Weeks . | P Valuea . |

| History of CT (ever) | ||||||

| Yes | 5 | 3.6 | .02 | 13 | 2.0 | .12 |

| No | 3 | 8.7 | 6 | 8.7 | ||

| History of CT (past 12 months) | ||||||

| Yes | 5 | 3.6 | .02 | 9 | 2.0 | .82 |

| No | 3 | 8.7 | 10 | 1.1 | ||

| Concurrent rectal CT | ||||||

| Yes | 5 | 6.0 | .33 | 7 | 6.0 | .03 |

| No | 3 | 3.6 | 12 | 1.1 | ||

| HIV status | ||||||

| Living with HIV | 1 | 2.0 | .25 | 7 | 1.1 | .09 |

| Not living with HIV | 7 | 6.0 | 12 | 3.6 | ||

| Concurrent pharyngeal gonorrhea | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | 6.0 | .88 | 5 | 3.6 | .34 |

| No | 5 | 8.7 | 14 | 2.0 | ||

| . | Primary Analysis . | Sensitivity Analysis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | n (N = 8) . | Median Duration, Weeks . | P Valuea . | n (N = 19) . | Median Duration, Weeks . | P Valuea . |

| History of CT (ever) | ||||||

| Yes | 5 | 3.6 | .02 | 13 | 2.0 | .12 |

| No | 3 | 8.7 | 6 | 8.7 | ||

| History of CT (past 12 months) | ||||||

| Yes | 5 | 3.6 | .02 | 9 | 2.0 | .82 |

| No | 3 | 8.7 | 10 | 1.1 | ||

| Concurrent rectal CT | ||||||

| Yes | 5 | 6.0 | .33 | 7 | 6.0 | .03 |

| No | 3 | 3.6 | 12 | 1.1 | ||

| HIV status | ||||||

| Living with HIV | 1 | 2.0 | .25 | 7 | 1.1 | .09 |

| Not living with HIV | 7 | 6.0 | 12 | 3.6 | ||

| Concurrent pharyngeal gonorrhea | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | 6.0 | .88 | 5 | 3.6 | .34 |

| No | 5 | 8.7 | 14 | 2.0 | ||

Abbreviation: CT, Chlamydia trachomatis; HIV, with human immunodeficiency virus.

P value from exact log-rank test.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimate for duration of pharyngeal chlamydia (in days). A, Primary analysis definition of incidence. B, Sensitivity analysis definition of incidence.

All individuals with incident pharyngeal chlamydia in primary analysis reported at least some sexual exposure at the mouth/pharynx in the week prior to the first positive CT test result. Reported behaviors include (with oral being participant’s role) oral–penile sex (7 of 8; 88%), oral–anal sex/rimming (3 of 8; 38%), and kissing (7 of 8; 88%); these were not mutually exclusive. Of note, participant 16, who had an infection that appeared to be 15 weeks in duration, reported oral–penile sex (ie, giving oral sex) during 13 of the 15 weeks in which the participant tested CT positive. In our sensitivity analysis, for 4 (21%) of 19 incident infections, participants did not report any sexual exposure at the mouth/pharynx in the week prior to the incident infection; all 4 were single weeks of a positive pharyngeal chlamydia test. Reported behaviors in the week prior to an incident pharyngeal chlamydia infection (for the sensitivity definition) included oral–penile sex (9 of 19; 47%), oral–anal sex/rimming (5 of 19; 26%), and kissing (13 of 19; 68%). Sore throat was reported by 1 (13%) of 8 participants in primary analysis and 4 (21%) of 19 participants in secondary analysis.

DISCUSSION

In this natural history study, we found that the prevalence of pharyngeal chlamydia was low (1.4%) and that the incidence was 11 per 100 PY. The median duration of pharyngeal chlamydia was 6 weeks and was shorter for individuals with a history of chlamydial infection. All individuals with an incident pharyngeal infection (in primary analysis) reported some sexual exposure at the mouth/pharynx. We found that having a single week of a CT-positive pharyngeal specimen was relatively common and that many of these single-week infections were not proceeded by any reported sexual activity. Taken together, our results suggest that many positive pharyngeal chlamydia infections may not be “true infections” or may be relatively transient or intermittent infections. Thus, the contribution of pharyngeal CT to sustained population-level transmission of CT remains somewhat unclear.

The prevalence of pharyngeal chlamydia we observed (1.4%) is consistent with a number of studies and meta-analyses that have reported prevalences of 1%–3% among populations of MSM, men who have sex with women, and women [1, 3–5]. The incidence of pharyngeal chlamydia in our study (11 per 100 PY in primary analysis) was more than 10 times higher than what was previously observed in a prospective cohort study of MSM in Australia (0.58 per 100 PY) that calculated incidence based on annual testing [17]. Given the relatively short duration of infection that we observed, it is likely that many infections in that cohort may have been missed. However, it is also possible that our cohort, which was a group at particularly high risk of STI, experienced an exceptionally high incidence of pharyngeal CT.

The incidence estimates from our sensitivity analysis where we considered a single week of a positive pharyngeal chlamydia test to be an incident infection was much higher, at 27 per 100 PY. The frequency of these single-week positive specimens merits discussion. Of 19 incident cases in our sensitivity analysis, 11 (57%) were positive only for a single week, and most of these (8 of 11) were not censored. There are a number of possible explanations for what these single-week specimens represent. First, it is likely that these pharyngeal CT “infections” likely resolved on their own, as previous studies have found that 35%–50% of individuals will spontaneously clear their pharyngeal chlamydia infection in the time between screening and treatment [6–8]. Second, it is also possible that these were not “true infections” (ie, CT was not infecting cells in the pharynx) but rather detection of CT nucleic acid from nonviable organisms [18] or detection of viable bacteria that were only transiently present in the throat. Indeed, for more than one-third (4 of 11) of these single-week positive specimens, participants did not report any sexual exposure at the mouth/pharynx. Lending support to this explanation is the fact that participants had concurrent rectal CT for 7 of 19 infections and could have contaminated the pharyngeal specimen with CT nucleic acid from the rectal infection. Third, it is possible that pharyngeal CT infections may actually represent chronic infections, where CT nucleic acid is only detected intermittently but the infection is long-lasting in the pharynx. Given that the clinical significance of pharyngeal chlamydia is unclear, that a high proportion of pharyngeal CT infections will spontaneously clear within 1 week, and that many pharyngeal CT NAATs may be positive in the absence of viable bacteria [18], our results support current US national screening guidelines [2], which do not recommend routine pharyngeal chlamydia screening.

We found that the duration of pharyngeal CT was approximately 6 weeks, which is considerably shorter than in a previous study by Chow and colleagues who estimated that the duration of pharyngeal chlamydia is 95 weeks [19]. However, that study calculated duration based on the aforementioned estimated incidence of 0.58 per 100 PY, which may have led to an overestimate of duration. Importantly, nearly a quarter of infections among our study population were censored due to antibiotic use, which truncated the duration that we observed; the true duration probably lies somewhere in between the 2 estimates. Notably, we observed that the duration of pharyngeal chlamydia was significantly shorter for individuals who reported a previous chlamydial infection. This suggests that the immune response resulting from previous exposure to CT, perhaps at any anatomic site, may play a role in rapid clearance of pharyngeal CT infections.

Our overall goal for this analysis was to better understand the epidemiologic parameters for pharyngeal CT to characterize its role in ongoing, population-level CT transmission. The transmission dynamics of chlamydia are complex, given that a single sexual encounter may include multiple sexual acts that expose different anatomic sites (urogenital tract, rectum, pharynx) and that CT could be transmitted between partners and within a single person during these sex acts [12]. There have been efforts to quantify some of these transmission pathways, specifically from the pharynx to the urethra. Bernstein and colleagues [9] found that 4.8% of San Francisco MSM whose only reported urethral exposure was the mouth/pharynx tested positive for CT, which was similar to that among MSM who reported condomless, insertive anal sex. Using clinic records from MSM in Seattle, our group previously reported [11] that the proportion of symptomatic chlamydial urethritis attributable to insertive oral sex was 2.7%. These studies suggest that transmission of CT from the pharynx does occur to some extent. However, even if transmission efficiency from the pharynx were high, the extent to which pharyngeal CT contributes to population-level transmission remains unclear.

Our study has several strengths. The frequency of specimen and survey data collection (weekly) allowed us to directly measure pharyngeal chlamydia incidence and duration, in one of the first studies of its kind. There are also several important limitations. First, we used NAAT, which tests for CT nucleic acid and may be positive in the absence of viable, replicating bacteria. This may have led to an overestimate of incidence and duration. However, in our primary analysis, we only counted infections as incident infections if there were 2 consecutive weeks of a positive test result. This may have reduced the likelihood of inappropriately capturing positive tests that did not represent “true infections.” Second, nearly one-quarter of infections were censored due to antibiotic use, which may have truncated the true duration of infections. Third, reporting of sexual behavior and antibiotic use is subject to recall bias. However, we used weekly surveys to minimize potential recall bias and confirmed data on antibiotic use and type with participants’ medical records, if possible. Third, this was a population that was, by design, at high risk of acquiring extragenital STIs; thus, incidence estimates may not be generalizable to broader populations.

In conclusion, we found that pharyngeal chlamydia often spontaneously clears and that, compared with other extragenital STIs such as pharyngeal gonorrhea (incidence of 32 per 100 PY and duration of 16 weeks) [14] and rectal chlamydia (incidence of 47 per 100 PY and duration of 13 weeks) [13], pharyngeal CT has a much lower incidence and duration. Our results add to the literature on pharyngeal CT epidemiological parameters, which previously established that pharyngeal chlamydia is an uncommon STI. Quantifying these transmission parameters allows us to better understand population-level transmission to help determine whether or not routine screening of pharyngeal CT is warranted to disrupt transmission. Our results intimate that pharyngeal CT infection is not likely to be a major driver in CT transmission at the population level, but the full extent of pharyngeal CT’s role in transmission remains unclear.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank our study participants and the Public Health–Seattle & King County Sexual Health Clinic for donating study space. We thank Micaela Haglund and Winnie Yeung for recruiting and coordinating with study participants. We also thank Rushlenne Pascual and Daphne Hamilton from the University of Washington Neisseria Reference Laboratory for laboratory support and Tanya Avoundjian for figure design.

Financial support. This work was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K23 AI113185 to L. A. B.). Specimen collection kits and test reagents were provided in-kind by Hologic Inc (San Diego, CA). REDCap (data collection and management system) at the University of Washington’s Institute for Translation Health Sciences is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award UL1 TR002319. This work was additionally supported by the University of Washington/Fred Hutch Center for AIDS Research, an NIH–funded program under award AI027757, which is supported by the following NIH institutes and centers: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Health, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute on Aging, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases.

Presented in part: STI & HIV 2021 World Congress (virtual), 14–17 July 2021.

References

Author notes

Potential conflicts of interest. C. M. K., O. O. S., M. R. G., and L. A. B. report research support from Hologic, Inc. L. A. B. and O. O. S. have received research support from SpeeDX outside of the submitted work. L. A. B. has received research support and consulting fees from Nabriva unrelated to the submitted work; has served as an unpaid volunteer on the data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) for the GC Vaccine trial; and has served as a paid medical consultant for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Division of Sexually Transmitted Disease Prevention. J. P. H. reports support from NIH and reports serving on the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Network DSMB. All remaining authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.