-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Carl Boodman, Carol Holmes, Charles Bernstein, Paul Van Caeseele, John Embil, A 41-Year-Old Female With Sudden-Onset Abdominal Pain and Nausea, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 74, Issue 12, 15 June 2022, Pages 2249–2251, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab927

Close - Share Icon Share

A 41-year-old female presented to a walk-in clinic 1 day after an acute onset of nausea and severe sharp epigastric pain. The patient’s medical history was notable for Helicobacter pylori infection treated 1 year earlier. Her past surgical history included a remote appendectomy and carpel tunnel release. The patient did not take medications regularly and did not smoke, drink alcohol, or use recreational drugs. The patient denied fever, chills, diarrhea, and rash. The onset of abdominal pain occurred 2 hours after ingesting uncooked sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) purchased on-sale from a supermarket earlier that day. The Pacific salmon was prepared uncooked with salt and spices and eaten immediately in 2 large sandwiches. After the onset of abdominal pain, the patient examined the remaining salmon and saw round worms emerging from the fish flesh (Figure 1).

A piece of sockeye salmon was submitted to Cadham Provincial Laboratory for parasitic analysis. Visualization of the salmon with the naked eye revealed a white nematode larva approximately 22 mm long and 0.3 mm wide, consistent with an L3 larva of the Anisakis simplex complex. Pseudoterranova larvae, which are rarely found in salmon, are yellow–brown in color and larger than those of Anisakis, extending to 50 mm in length and 1.2 mm in width.

What Is Your Diagnosi

Answer: Anisakidosis

Anisakidosis, also known as cod worm, herring worm, and seal worm, is a human parasitic infection caused by nematodes of the Anisakidae family [1]. Anisakidosis occurs after ingestion of undercooked fish or squid infected with third-stage larval nematodes [1]. Anisakidosis is a hypernym that includes anisakiasis (infection with parasites from the Anisakis genus) as well as pseudoterranovosis (infection with parasites from the Pseudoterranova genus) [1]. While cod, halibut, and red snapper are often infected with Pseudoterranova spp. parasites, salmon is most often infected with parasites of the Anisakis simplex complex [1–5]. The majority of salmon are infected with Anisakis nematodes; prevalence may be as high as 72%–87% [3, 4].

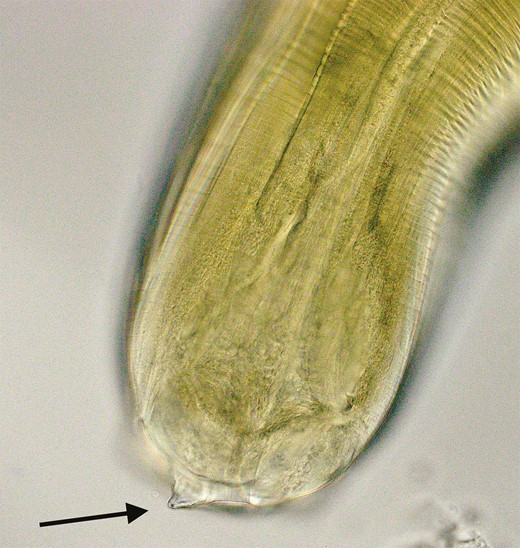

Anisakis’ primary hosts are cetaceans such as whales and dolphins. Humans are accidental hosts. Upon ingestion of undercooked fish or squid that contains Anisakidae parasites, the larvae pierce the gastric or intestinal mucosa using a “boring tooth” (see Figure 2). Unable to complete their life cycle within the human host, the larvae die, triggering an inflammatory eosinophilic reaction and mucosal erosions associated severe abdominal pain. The acute pain usually resolves within a few days; however, persistent mucosal erosions may cause milder symptoms for weeks [1, 6]. Rarely, larvae perforate the intestinal wall causing larva migrans, ascites, and intraperitoneal abscesses [1]. Anisakidosis may also be associated with allergic manifestations such as urticaria, angioedema, or anaphylaxis [7].

Larva removed from the salmon was treated with lactophenol solution for 5 minutes to clear debris and highlight anatomical structures. Examination of the cephalic end with light microscopy (40× objective lens) demonstrates the boring tooth used to penetrate the gastric and intestinal mucosa.

Clinical diagnosis involves the chronological onset of acute abdominal or allergic symptomatology within hours to days of ingesting undercooked seafood. Endoscopic visualization of the larvae confirms the diagnosis. Serology may be helpful in diagnosing extraintestinal or allergic anisakidosis [8]. As the larvae are visible to the naked eye, diagnosis may be corroborated by simply observing the uneaten seafood for nematodes, as occurred in our case.

Definitive treatment of gastric anisakidosis involves endoscopic removal of the embedded larvae. There is limited evidence for albendazole and ivermectin [6, 9]. Anisakidosis may be prevented by cooking seafood to 60ºC–70ºC for 1 minute or blast freezing at –35ºC for 24 hours (or until solid) or freezing for longer at higher temperatures [10, 11]. Specific temperature and duration recommendations for fish intended to be safely eaten raw differ among the food safety guidelines of different jurisdictions [10]. Pickling, salting, and smoking are not usually sufficient to kill Anisakidae nematodes [1, 10].

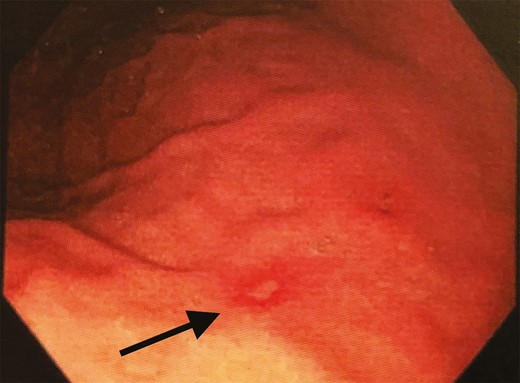

In our case, the patient had ongoing epigastric pain and nausea 1 week after salmon ingestion, prompting infectious disease and gastroenterology consultations. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy occurred 9 days after salmon ingestion and revealed gastric mucosal erosions but no remaining larvae (Figure 3). Histopathology of the gastric tissue demonstrated eosinophilic infiltration.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy demonstrated multiple erosions within surrounding erythema along the gastric body and antrum. Histopathology of these lesions demonstrated eosinophilic infiltration consistent with anisakidosis.

The patient was provided with a 2-week course of omeprazole for symptom relief and to aid mucosal healing. She was also provided with a 2-day course of ivermectin (2 µg/kg by mouth daily for 2 days) upon request to kill any remaining parasites. We recognize that the evidence for ivermectin is sparse; however, we routinely experience delays in obtaining albendazole at our center as it requires Special Access Approval in Canada. Over the next 14 days, her symptoms gradually resolved.

Additional photos of Anisakis nematodes are available in Supplementary Figures 4 and 5.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the parasitology laboratory team at Cadham Provincial Laboratory (specifically Paul Li) for help enabling parasite photography and willingness to keep old salmon in his laboratory fridge.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.