-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Julia C Dombrowski, Michael R Wierzbicki, Lori M Newman, Jonathan A Powell, Ashley Miller, Dwyn Dithmer, Olusegun O Soge, Kenneth H Mayer, Doxycycline Versus Azithromycin for the Treatment of Rectal Chlamydia in Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Randomized Controlled Trial, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 73, Issue 5, 1 September 2021, Pages 824–831, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab153

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Azithromycin and doxycycline are both recommended treatments for rectal Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) infection, but observational studies suggest that doxycycline may be more effective.

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial compared azithromycin (single 1-g dose) versus doxycycline (100 mg twice daily for 7 days) for the treatment of rectal CT in men who have sex with men (MSM) in Seattle and Boston. Participants were enrolled after a diagnosis of rectal CT in clinical care and underwent repeated collection of rectal swabs for nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) at study enrollment and 2 weeks and 4 weeks postenrollment. The primary outcome was microbiologic cure (CT-negative NAAT) at 4 weeks. The complete case (CC) population included participants with a CT-positive NAAT at enrollment and a follow-up NAAT result; the intention-to-treat (ITT) population included all randomized participants.

Among 177 participants enrolled, 135 (76%) met CC population criteria for the 4-week follow-up visit. Thirty-three participants (19%) were excluded because the CT NAAT repeated at enrollment was negative. Microbiologic cure was higher with doxycycline than azithromycin in both the CC population (100% [70 of 70] vs 74% [48 of 65]; absolute difference, 26%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 16–36%; P < .001) and the ITT population (91% [80 of 88] vs 71% [63 of 89]; absolute difference, 20%; 95% CI, 9–31%; P < .001).

A 1-week course of doxycycline was significantly more effective than a single dose of azithromycin for the treatment of rectal CT in MSM.

NCT03608774.

Incidence rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States have risen substantially over the last decade [1]. Rectal Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) is the most common bacterial STI among MSM [1, 2], but because it rarely causes symptoms, the infection often remains undetected in the absence of extragenital screening. National surveillance data demonstrated 10–21% test positivity for rectal CT among MSM in STI clinics in 2018 and 18% among MSM in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) care in 2013–2014 [1, 3]. Among a nonclinical population of asymptomatic MSM recruited in 5 cities, 7% had rectal CT [2]. Rectal CT can lead to urethral CT infections in male partners [4] and increases the risk of HIV acquisition by approximately 2-fold [5, 6]. Thus, effective detection and treatment of rectal CT is central to chlamydia control among MSM and may contribute to HIV prevention.

Although the 2015 STI treatment guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend both doxycycline and azithromycin as first-line treatments for rectal CT [7], retrospective studies suggest that doxycycline is more effective. A meta-analysis of 8 observational studies estimated the efficacy of a 7-day course of doxycycline to be 99.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 98.6–100%) compared with 82.9% (76.0–89.8%) for single-dose azithromycin [8]. However, the relative effectiveness of these regimens remains uncertain without a prospective study. Definitive data are needed to inform clinical practice, particularly because many clinicians prefer to use azithromycin due to the simplicity of a single-dose regimen [9]. We conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of single-dose azithromycin versus a 7-day course of doxycycline for the treatment of rectal CT in MSM.

METHODS

Study Design

The study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial among MSM with rectal CT detected by a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) in clinical care. We randomized study participants to azithromycin (single 1-g oral dose) or doxycycline (100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days) plus matching placebo. Participants repeated rectal swabs for CT NAAT at the time of study enrollment and 2 weeks and 4 weeks after enrollment. The study was conducted at the Public Health—Seattle & King County Sexual Health Clinic in Seattle, Washington, and Fenway Health in Boston, Massachusetts.

The primary outcome was the proportion of participants with microbiologic cure (CT-negative NAAT) in each study arm at 4 weeks (visit 3). Secondary outcomes included the proportion of participants with microbiologic cure at 2 weeks and the proportion with microbiologic cure at 2 and 4 weeks stratified by infection with lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) biovar CT. Exploratory outcomes included the proportion of participants with microbiologic cure in subgroups defined by HIV status, medication adherence, and rectal symptoms. We explored the impact of antacid and rectal lubricant or douche use on treatment effectiveness based on the hypothesis that these might alter the concentration of azithromycin in the rectum [10].

Population

Eligible individuals were male sex at birth (inclusive of any gender identity), 18 years or older, had at least 1 male sex partner in the past 12 months, and agreed to abstain from condomless receptive anal sex during the study. Participants were excluded if they had a clinical diagnosis of acute proctitis [7], concomitant untreated gonorrhea or primary or secondary syphilis, known allergy to tetracyclines or macrolide antibiotics, or had received antimicrobial therapy active against CT within 21 days of the positive rectal CT NAAT result or between the date of the test and study enrollment.

Randomization and Blinding

Participants were randomized to a treatment arm in a 1-to-1 ratio using site-stratified, permuted, blocked randomization. Participants, clinical study staff, data entry personnel, and laboratory personnel were blinded to treatment assignment. The study drug was provided in identical kits with overencapsulated pills and identical placebos containing lactose monohydrate.

Study Visit Procedures

During the enrollment visit, clinicians assessed whether participants had rectal symptoms, such as discomfort, irritation, or itching; examined inguinal lymph nodes; collected information on HIV status and antiretroviral therapy or pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP); and collected information on sexual behavior in the past 60 days, including partner number, anal and other sex acts, condom use, lubricant use, and douching. Research staff observed participants taking the dose of azithromycin (or placebo) plus 1 dose of doxycycline (or placebo) but did not otherwise provide adherence support. At follow-up visits, adherence to the study medications was assessed by self-report and, if available, pill count from returned study drug. We collected limited data on adverse events since the safety profile of both study medications is well documented.

Rectal swabs were collected by the study clinician or self-collected by participants in the clinic per clinic standard practice. In addition, after February 2019, participants could mail in self-collected rectal swabs at the 2- and 4-week time points. Prior studies and CDC guidelines support the use of patient-collected swabs as comparable to clinician-collected swabs for rectal CT diagnosis [7, 11–13]. Participants with a positive or indeterminate rectal CT NAAT result at the final study visit were notified by an unblinded clinician who ensured appropriate re-treatment. The NAAT results from the 2-week visit were not released during the study or used for clinical care.

Laboratory Methods

All laboratory testing was performed in the University of Washington (UW) Global Health STI Laboratory. CT NAAT was conducted using the Aptima Combo 2 Assay (Hologic, Inc, San Diego, CA, USA). All specimens positive for CT at the time of study enrollment were tested using a validated LGV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [14].

Sample Size

The trial utilized a 2-staged group sequential design using O’Brien-Fleming boundaries with 1 semi-blinded interim analysis of the primary outcome once half the target evaluable population had been enrolled with primary endpoint data and a stopping rule based on efficacy. An overall type I error rate of 5% was set for the analyses. To determine the sample size, we assumed a range of cure rates of doxycycline and azithromycin consistent with published studies. A sample size of 246 participants would have more than 80% power to detect a 10% or greater difference across a range of cure rates. Anticipating 10% ineligibility for the primary analysis, the enrollment target was 274 participants. We calculated the probability of stopping the trial at the interim analysis to be less than 1% if the cure proportions were equal and 23% if cure proportions of doxycycline and azithromycin were 97% and 87%, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

The primary, secondary, and exploratory study outcomes were analyzed in the complete case (CC) population, which included participants with a CT-positive NAAT at enrollment and at the corresponding follow-up time point. Additionally, we evaluated the primary and secondary outcomes in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, which included all enrolled participants, and the per-protocol (PP) population, which included participants who met the CC population criteria and reported no condomless anal intercourse or receipt of antibiotics effective against CT during the study, sufficiently adhered to the study medication, and completed a 4-week study visit in the specified time frame. In the absence of a defined minimally effective regimen of doxycycline for the treatment of rectal CT, we defined “sufficient adherence” a priori as completing the first doses of study medication under observation and reporting at least 9 additional doses of doxycycline/placebo within 10 days.

For the primary analysis comparing 4-week microbiologic cure outcomes in the 2 treatment groups in the CC population, a 2-sided Pearson chi-square test was used with significance levels defined by the O’Brien-Fleming boundaries. To derive the P value, the point estimate, and CI for the difference in cure proportions, stage-wise ordering of the sample space was used [15]. The resulting P value, median unbiased estimate, and CI are reported here. For the analyses of the 4-week and 2-week outcomes in the ITT and PP populations, a significance level of 5% was used. For ITT analyses, subjects with missing cure outcomes were classified as treatment failures and outcomes were imputed as microbiologic failures.

For exploratory analyses, we conducted subgroup analyses of the 4-week cure outcomes stratified by HIV status, LGV biovar status, rectal symptoms (symptomatic or asymptomatic), adherence, and antacid medication use. Based on the high level of effectiveness in the doxycycline treatment group, we decided post hoc to report the comparisons only within the azithromycin arm and excluded the adherence comparison.

Human Research Protections

The study protocol was approved by Institutional Review Boards at the UW and Fenway Health. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03608774). A Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) provided oversight, including review of data at specified times during the study for participant and overall study progress, semi-blinded interim analysis results, serious adverse events, and, at the conclusion of the trial, safety data.

RESULTS

Study Population

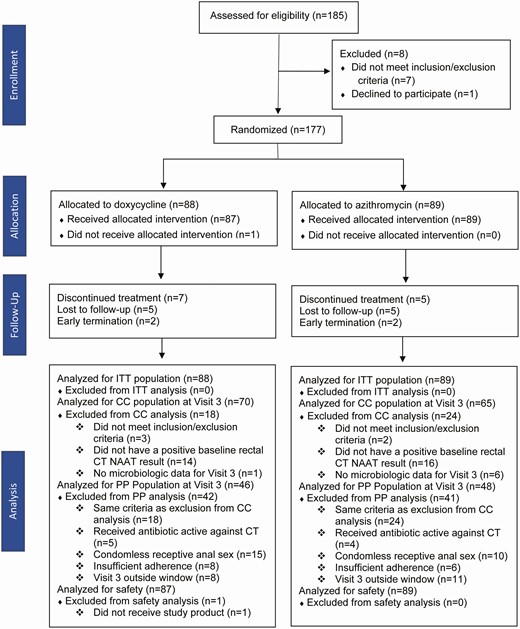

Between July 2018 and February 2020, 177 participants were enrolled and randomized to doxycycline or azithromycin (Figure 1). Enrollment ended after the DSMB recommended stopping based on efficacy in accordance with the prespecified stopping rule for the interim analysis. Enrolled subjects who were ongoing follow-up at the time of the interim analysis were not included in the analysis provided to the DSMB. The data from these subjects were incorporated in the analyses reported in this study [16, 17].

Study flow chart. Abbreviations: CC, complete case; CT, Chlamydia trachomatis; ITT, intention-to-treat; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification testing; PP, per protocol.

Seventy six percent of enrolled participants (n = 135) met CC population criteria at 4 weeks, and the most common exclusion reason (n = 33; 19% of all enrolled) was a negative result on the CT NAAT repeated at enrollment. This proportion did not differ substantially between the 2 study sites (17% and 21%). Ninety-four participants were included in the PP population, with condomless receptive anal sex during the study being the most common reason for exclusion from the PP population among participants included in the CC population (n = 25; 19% of the CC population).

The median age of participants was 34 years, and 95% identified as cisgender men (Table 1). Sixty-three percent were White, 21% were Hispanic/Latino, 5% were Black, and 4% were Asian or Pacific Islander. Over half of participants (54%) were HIV-seronegative and taking HIV PrEP and 15% were HIV-seropositive. A minority had rectal symptoms (18%) or inguinal lymphadenopathy (4%).

| . | Doxycycline (n = 88)a . | Azithromycin (n = 89) . | All Subjects (n = 177) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Cisgender male | 83 (94) | 85 (96) | 168 (95) |

| Transgender, nonbinary, other | 4 (5) | 4 (4) | 8 (5) |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 34 (12) | 34 (11) | 34 (11) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 58 (66) | 54 (61) | 112 (63) |

| Black | 5 (6) | 3 (3) | 8 (5) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 13 (15) | 12 (14) | 25 (14) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (1) | 1(1) | 2 (1) |

| Multiracial | 6 (7) | 16 (18) | 22 (12) |

| Missing | 5 (6) | 3 (3) | 8 (5) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 21 (24) | 16 (18) | 37 (21) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 67 (76) | 71 (80) | 138 (78) |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| HIV statusb; ART and PrEP status, n (%) | |||

| Positive, on ART | 14 (16) | 12 (14) | 26 (15) |

| Positive, not on ART | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Negative, on PrEP | 44 (50) | 52 (58) | 96 (54) |

| Negative, not on PrEPc | 29 (33) | 22 (25) | 51 (29) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 4 (2) |

| Rectal symptoms,d n (%) | |||

| Yes | 13 (15) | 18 (20) | 31 (18) |

| No | 74 (84) | 71 (80) | 145 (82) |

| Inguinal lymphadenopathy,d n (%) | |||

| Yes | 4 (5) | 3 (3) | 7 (4) |

| No | 83 (94) | 86 (97) | 169 (95) |

| . | Doxycycline (n = 88)a . | Azithromycin (n = 89) . | All Subjects (n = 177) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Cisgender male | 83 (94) | 85 (96) | 168 (95) |

| Transgender, nonbinary, other | 4 (5) | 4 (4) | 8 (5) |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 34 (12) | 34 (11) | 34 (11) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 58 (66) | 54 (61) | 112 (63) |

| Black | 5 (6) | 3 (3) | 8 (5) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 13 (15) | 12 (14) | 25 (14) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (1) | 1(1) | 2 (1) |

| Multiracial | 6 (7) | 16 (18) | 22 (12) |

| Missing | 5 (6) | 3 (3) | 8 (5) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 21 (24) | 16 (18) | 37 (21) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 67 (76) | 71 (80) | 138 (78) |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| HIV statusb; ART and PrEP status, n (%) | |||

| Positive, on ART | 14 (16) | 12 (14) | 26 (15) |

| Positive, not on ART | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Negative, on PrEP | 44 (50) | 52 (58) | 96 (54) |

| Negative, not on PrEPc | 29 (33) | 22 (25) | 51 (29) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 4 (2) |

| Rectal symptoms,d n (%) | |||

| Yes | 13 (15) | 18 (20) | 31 (18) |

| No | 74 (84) | 71 (80) | 145 (82) |

| Inguinal lymphadenopathy,d n (%) | |||

| Yes | 4 (5) | 3 (3) | 7 (4) |

| No | 83 (94) | 86 (97) | 169 (95) |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

aOne participant in the doxycycline group did not have baseline data available.

bBased on participant self-report.

cAt baseline; 6 subjects started PrEP between study entry and follow-up visits.

dSymptoms that met the clinical definition of proctitis were excluded.

| . | Doxycycline (n = 88)a . | Azithromycin (n = 89) . | All Subjects (n = 177) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Cisgender male | 83 (94) | 85 (96) | 168 (95) |

| Transgender, nonbinary, other | 4 (5) | 4 (4) | 8 (5) |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 34 (12) | 34 (11) | 34 (11) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 58 (66) | 54 (61) | 112 (63) |

| Black | 5 (6) | 3 (3) | 8 (5) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 13 (15) | 12 (14) | 25 (14) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (1) | 1(1) | 2 (1) |

| Multiracial | 6 (7) | 16 (18) | 22 (12) |

| Missing | 5 (6) | 3 (3) | 8 (5) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 21 (24) | 16 (18) | 37 (21) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 67 (76) | 71 (80) | 138 (78) |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| HIV statusb; ART and PrEP status, n (%) | |||

| Positive, on ART | 14 (16) | 12 (14) | 26 (15) |

| Positive, not on ART | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Negative, on PrEP | 44 (50) | 52 (58) | 96 (54) |

| Negative, not on PrEPc | 29 (33) | 22 (25) | 51 (29) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 4 (2) |

| Rectal symptoms,d n (%) | |||

| Yes | 13 (15) | 18 (20) | 31 (18) |

| No | 74 (84) | 71 (80) | 145 (82) |

| Inguinal lymphadenopathy,d n (%) | |||

| Yes | 4 (5) | 3 (3) | 7 (4) |

| No | 83 (94) | 86 (97) | 169 (95) |

| . | Doxycycline (n = 88)a . | Azithromycin (n = 89) . | All Subjects (n = 177) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Cisgender male | 83 (94) | 85 (96) | 168 (95) |

| Transgender, nonbinary, other | 4 (5) | 4 (4) | 8 (5) |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 34 (12) | 34 (11) | 34 (11) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 58 (66) | 54 (61) | 112 (63) |

| Black | 5 (6) | 3 (3) | 8 (5) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 13 (15) | 12 (14) | 25 (14) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (1) | 1(1) | 2 (1) |

| Multiracial | 6 (7) | 16 (18) | 22 (12) |

| Missing | 5 (6) | 3 (3) | 8 (5) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 21 (24) | 16 (18) | 37 (21) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 67 (76) | 71 (80) | 138 (78) |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| HIV statusb; ART and PrEP status, n (%) | |||

| Positive, on ART | 14 (16) | 12 (14) | 26 (15) |

| Positive, not on ART | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Negative, on PrEP | 44 (50) | 52 (58) | 96 (54) |

| Negative, not on PrEPc | 29 (33) | 22 (25) | 51 (29) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 4 (2) |

| Rectal symptoms,d n (%) | |||

| Yes | 13 (15) | 18 (20) | 31 (18) |

| No | 74 (84) | 71 (80) | 145 (82) |

| Inguinal lymphadenopathy,d n (%) | |||

| Yes | 4 (5) | 3 (3) | 7 (4) |

| No | 83 (94) | 86 (97) | 169 (95) |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

aOne participant in the doxycycline group did not have baseline data available.

bBased on participant self-report.

cAt baseline; 6 subjects started PrEP between study entry and follow-up visits.

dSymptoms that met the clinical definition of proctitis were excluded.

Microbiologic Cure

Microbiologic cure at 4 weeks was higher with doxycycline than azithromycin in all analysis populations (Table 2). In the CC population, the cure proportion was 100% (95% CI, 90–100%) in the doxycycline arm versus 74% (95% CI, 56–86%) in the azithromycin arm, with an absolute difference of 26% (95% CI, 16–36%; P < .001). In the ITT population, the cure rate for doxycycline was 91% (95% CI, 83–95%) versus 71% (95% CI, 61–79%) for azithromycin (P < .001). Cases imputed as treatment failures in the doxycycline group were driven by loss to follow-up (n = 7); only 1 participant had a positive NAAT at 4 weeks.

Microbiologic Cure at 4 Weeks, by Treatment Group, in Each Analysis Population

| . | Complete Case Populationa . | . | Intent-to-Treat Populationb . | . | Per Protocol Populationc . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Doxycycline (n = 70) . | Azithromycin (n = 65) . | Doxycycline (n = 88) . | Azithromycin (n = 89) . | Doxycycline (n = 46) . | Azithromycin (n = 48) . |

| Participants with microbiologic cure, n | 70 | 48 | 80 | 63 | 46 | 37 |

| Participants with microbiologic cure, % (95% CI) | 100 (90–100) | 74 (56–86) | 91 (83–95) | 71 (61–79) | 100 (92- 100) | 77 (63–87) |

| Difference in proportion, % | 26 (16–36) | 20 (9 – 31) | 23 (11 – 37) | |||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| . | Complete Case Populationa . | . | Intent-to-Treat Populationb . | . | Per Protocol Populationc . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Doxycycline (n = 70) . | Azithromycin (n = 65) . | Doxycycline (n = 88) . | Azithromycin (n = 89) . | Doxycycline (n = 46) . | Azithromycin (n = 48) . |

| Participants with microbiologic cure, n | 70 | 48 | 80 | 63 | 46 | 37 |

| Participants with microbiologic cure, % (95% CI) | 100 (90–100) | 74 (56–86) | 91 (83–95) | 71 (61–79) | 100 (92- 100) | 77 (63–87) |

| Difference in proportion, % | 26 (16–36) | 20 (9 – 31) | 23 (11 – 37) | |||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CT, Chlamydia trachomatis; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification testing.

aParticipants who had positive rectal CT NAAT at baseline and follow-up microbiologic data.

bAll enrolled participants.

cParticipants who had a positive rectal CT NAAT at baseline, follow-up microbiologic data, reported no condomless anal intercourse or receipt of antibiotics effective against CT during the study, adhered sufficiently to study medication, and completed visit 3 within the time frame specified in the protocol.

Microbiologic Cure at 4 Weeks, by Treatment Group, in Each Analysis Population

| . | Complete Case Populationa . | . | Intent-to-Treat Populationb . | . | Per Protocol Populationc . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Doxycycline (n = 70) . | Azithromycin (n = 65) . | Doxycycline (n = 88) . | Azithromycin (n = 89) . | Doxycycline (n = 46) . | Azithromycin (n = 48) . |

| Participants with microbiologic cure, n | 70 | 48 | 80 | 63 | 46 | 37 |

| Participants with microbiologic cure, % (95% CI) | 100 (90–100) | 74 (56–86) | 91 (83–95) | 71 (61–79) | 100 (92- 100) | 77 (63–87) |

| Difference in proportion, % | 26 (16–36) | 20 (9 – 31) | 23 (11 – 37) | |||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| . | Complete Case Populationa . | . | Intent-to-Treat Populationb . | . | Per Protocol Populationc . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Doxycycline (n = 70) . | Azithromycin (n = 65) . | Doxycycline (n = 88) . | Azithromycin (n = 89) . | Doxycycline (n = 46) . | Azithromycin (n = 48) . |

| Participants with microbiologic cure, n | 70 | 48 | 80 | 63 | 46 | 37 |

| Participants with microbiologic cure, % (95% CI) | 100 (90–100) | 74 (56–86) | 91 (83–95) | 71 (61–79) | 100 (92- 100) | 77 (63–87) |

| Difference in proportion, % | 26 (16–36) | 20 (9 – 31) | 23 (11 – 37) | |||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CT, Chlamydia trachomatis; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification testing.

aParticipants who had positive rectal CT NAAT at baseline and follow-up microbiologic data.

bAll enrolled participants.

cParticipants who had a positive rectal CT NAAT at baseline, follow-up microbiologic data, reported no condomless anal intercourse or receipt of antibiotics effective against CT during the study, adhered sufficiently to study medication, and completed visit 3 within the time frame specified in the protocol.

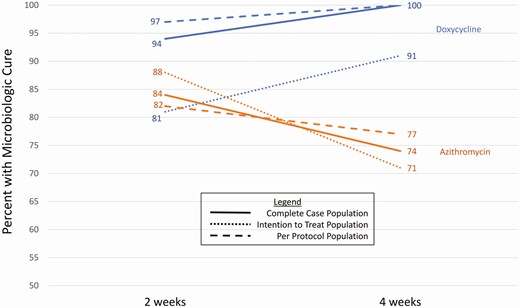

At the 2-week follow-up visit, doxycycline was more effective than azithromycin in all analysis populations. The absolute difference between doxycycline and azithromycin was 11% (95% CI, 0–22%) in the CC population, 7% (95% CI, −4 to 17%) in the ITT population, and 15% (95% CI, 4–27%) in the PP population. Among participants who received doxycycline, the proportion with microbiologic cure was lower at 2 weeks than at 4 weeks, but the opposite pattern was observed in participants who received azithromycin (Figure 2). Among participants in the CC population who received azithromycin, 8 of 56 (14%) who had a negative NAAT at 2 weeks had a positive NAAT again at 4 weeks.

Comparison of 2-week and 4-week cure percentage by treatment group and analysis population.

The LGV PCR was positive in CT specimens from 8 participants (6% of the 4-week CC population). These were equally distributed between the study arms (n = 4 in each). Among participants in Seattle, 6 (6% of 104) had LGV-biovar infections versus 2 (3% of 73) in Boston. All participants with LGV-biovar CT who received doxycycline had microbiologic cure at both 2 and 4 weeks, as did 3 of 4 (75%) who received azithromycin (25% absolute difference; 95% CI, −.28 to .70). Among participants with non-LGV CT biovars, the absolute difference between study arms was 26% (95% CI, .15–.38).

Medication Adherence and Sexual Behavior

In the CC population at 4 weeks, 131 of 135 participants (97%) met the definition of sufficient adherence to the 7-day course of doxycycline/placebo. Among 4 who reported insufficient adherence, 2 were randomized to each treatment, and all had microbiologic cure at 4 weeks.

Sexual behavior between enrollment and follow-up did not differ between treatment assignment groups (Table 3). Overall, 75 participants (45% of those with follow-up data) reported having receptive anal sex and 25 (14%) reported condomless anal sex.

Follow-up Sexually Transmitted Infection and Sexual History by Treatment Group

| . | Doxycycline (n = 88), n (% of total) . | Azithromycin (n = 89), n (% of total) . | All Subjects (n = 177), n (% of total) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any STI since enrollment | |||

| No | 84 (97) | 85 (96) | 169 (96) |

| Yes | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 7 (4) |

| Sexual behaviors during the study | |||

| Any receptive anal sex | 37 (45) | 38 (45) | 75 (45) |

| Condomless receptive anal sex | 15 (17) | 10 (11) | 25 (14) |

| Rimming | 18 (22) | 30 (35) | 48 (29) |

| Fisting | 2 (2) | 4 (5) | 6 (4) |

| Lubricant use during receptive anal sex | |||

| No | 47 (57) | 48 (56) | 95 (57) |

| Yes | 35 (43) | 37 (44) | 72 (43) |

| Silicone-based | 20 (67)a | 25 (76) | 45 (71) |

| Water-based | 17 (57) | 12 (36) | 29 (46) |

| Saliva | 17 (57) | 19 (58) | 36 (57) |

| Ejaculate | 4 (13) | 4 (12) | 8 (13) |

| Oil | 3 (10) | 3 (9) | 6 (10) |

| Other/unknown | 5 (17) | 7 (21) | 12 (19) |

| Rectal douches | |||

| No | 52 (63) | 52 (61) | 104 (62) |

| Yes | 30 (37) | 33 (39) | 63 (38) |

| Water | 29 (97)a | 32 (97) | 61 (97) |

| Fleet enema | 6 (20) | 4 (12) | 10 (16) |

| . | Doxycycline (n = 88), n (% of total) . | Azithromycin (n = 89), n (% of total) . | All Subjects (n = 177), n (% of total) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any STI since enrollment | |||

| No | 84 (97) | 85 (96) | 169 (96) |

| Yes | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 7 (4) |

| Sexual behaviors during the study | |||

| Any receptive anal sex | 37 (45) | 38 (45) | 75 (45) |

| Condomless receptive anal sex | 15 (17) | 10 (11) | 25 (14) |

| Rimming | 18 (22) | 30 (35) | 48 (29) |

| Fisting | 2 (2) | 4 (5) | 6 (4) |

| Lubricant use during receptive anal sex | |||

| No | 47 (57) | 48 (56) | 95 (57) |

| Yes | 35 (43) | 37 (44) | 72 (43) |

| Silicone-based | 20 (67)a | 25 (76) | 45 (71) |

| Water-based | 17 (57) | 12 (36) | 29 (46) |

| Saliva | 17 (57) | 19 (58) | 36 (57) |

| Ejaculate | 4 (13) | 4 (12) | 8 (13) |

| Oil | 3 (10) | 3 (9) | 6 (10) |

| Other/unknown | 5 (17) | 7 (21) | 12 (19) |

| Rectal douches | |||

| No | 52 (63) | 52 (61) | 104 (62) |

| Yes | 30 (37) | 33 (39) | 63 (38) |

| Water | 29 (97)a | 32 (97) | 61 (97) |

| Fleet enema | 6 (20) | 4 (12) | 10 (16) |

The denominator for percentages is the number of subjects with follow-up sexual history data. Abbreviation: STI, sexually transmitted infection.

aThe denominators for lubricant and douche types are the number of persons who reported using lubricants or douches, respectively.

Follow-up Sexually Transmitted Infection and Sexual History by Treatment Group

| . | Doxycycline (n = 88), n (% of total) . | Azithromycin (n = 89), n (% of total) . | All Subjects (n = 177), n (% of total) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any STI since enrollment | |||

| No | 84 (97) | 85 (96) | 169 (96) |

| Yes | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 7 (4) |

| Sexual behaviors during the study | |||

| Any receptive anal sex | 37 (45) | 38 (45) | 75 (45) |

| Condomless receptive anal sex | 15 (17) | 10 (11) | 25 (14) |

| Rimming | 18 (22) | 30 (35) | 48 (29) |

| Fisting | 2 (2) | 4 (5) | 6 (4) |

| Lubricant use during receptive anal sex | |||

| No | 47 (57) | 48 (56) | 95 (57) |

| Yes | 35 (43) | 37 (44) | 72 (43) |

| Silicone-based | 20 (67)a | 25 (76) | 45 (71) |

| Water-based | 17 (57) | 12 (36) | 29 (46) |

| Saliva | 17 (57) | 19 (58) | 36 (57) |

| Ejaculate | 4 (13) | 4 (12) | 8 (13) |

| Oil | 3 (10) | 3 (9) | 6 (10) |

| Other/unknown | 5 (17) | 7 (21) | 12 (19) |

| Rectal douches | |||

| No | 52 (63) | 52 (61) | 104 (62) |

| Yes | 30 (37) | 33 (39) | 63 (38) |

| Water | 29 (97)a | 32 (97) | 61 (97) |

| Fleet enema | 6 (20) | 4 (12) | 10 (16) |

| . | Doxycycline (n = 88), n (% of total) . | Azithromycin (n = 89), n (% of total) . | All Subjects (n = 177), n (% of total) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any STI since enrollment | |||

| No | 84 (97) | 85 (96) | 169 (96) |

| Yes | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 7 (4) |

| Sexual behaviors during the study | |||

| Any receptive anal sex | 37 (45) | 38 (45) | 75 (45) |

| Condomless receptive anal sex | 15 (17) | 10 (11) | 25 (14) |

| Rimming | 18 (22) | 30 (35) | 48 (29) |

| Fisting | 2 (2) | 4 (5) | 6 (4) |

| Lubricant use during receptive anal sex | |||

| No | 47 (57) | 48 (56) | 95 (57) |

| Yes | 35 (43) | 37 (44) | 72 (43) |

| Silicone-based | 20 (67)a | 25 (76) | 45 (71) |

| Water-based | 17 (57) | 12 (36) | 29 (46) |

| Saliva | 17 (57) | 19 (58) | 36 (57) |

| Ejaculate | 4 (13) | 4 (12) | 8 (13) |

| Oil | 3 (10) | 3 (9) | 6 (10) |

| Other/unknown | 5 (17) | 7 (21) | 12 (19) |

| Rectal douches | |||

| No | 52 (63) | 52 (61) | 104 (62) |

| Yes | 30 (37) | 33 (39) | 63 (38) |

| Water | 29 (97)a | 32 (97) | 61 (97) |

| Fleet enema | 6 (20) | 4 (12) | 10 (16) |

The denominator for percentages is the number of subjects with follow-up sexual history data. Abbreviation: STI, sexually transmitted infection.

aThe denominators for lubricant and douche types are the number of persons who reported using lubricants or douches, respectively.

HIV Status, Rectal Symptoms, and Antacid Medication Use

Among 8 HIV-seropositive participants randomized to azithromycin, all were cured at 4 weeks (100%; 95% CI, 68–100%) compared with 70% (38 of 54; 95% CI, 57–81%) of HIV-seronegative participants. Among 14 participants with rectal symptoms at baseline, 79% (95% CI, 52–92%) had cure with azithromycin compared with 73% (37 of 51; 95% CI, 59–83%) in those without symptoms. One participant in the azithromycin group who reported using antacid medication had a positive NAAT at 4 weeks.

Safety and Tolerance

One serious adverse event occurred, which was unrelated to the study. Additionally, 1 participant assigned doxycycline and 2 assigned azithromycin reported vomiting the study medication, 1 of whom (assigned azithromycin) terminated study participation early.

Discussion

In this randomized placebo-controlled trial, we found that a 7-day course of doxycycline was significantly more effective than a single dose of azithromycin for the treatment of rectal CT in MSM, with point estimate cure proportions of 100% for doxycycline and 74% for azithromycin in the CC population and 91% for doxycycline and 71% for azithromycin in the ITT population. Only 1 of 88 participants randomized to doxycycline had a positive NAAT at 4 weeks, with the remainder of noncures in the ITT population reflecting loss to follow-up. Although the proportion of participants with microbiologic cure in the doxycycline arm increased from 2 to 4 weeks postenrollment, the proportion with cure in the azithromycin arm decreased from 2 to 4 weeks. Infection with LGV-biovar CT was uncommon. Both treatments were safe and well tolerated.

Our main study finding confirms the results of previous observational studies [8, 9]. However, the effectiveness of azithromycin in our study (74%; 95% CI, 56–86%) was even lower than estimated in pooled results of retrospective studies (83%; 95% CI, 76–90%) and well below the 95% threshold generally considered acceptable for STI treatment. Our findings were comparable to those of a prospective study of women with CT, most of whom had concomitant rectal and urogenital infections, which found approximately 96% microbiologic cure with doxycycline and 79% with azithromycin at the rectum [18]. Forthcoming results from an Australian study of rectal CT in MSM will add to the body of evidence on this topic [19]. Taken together, the existing studies conclusively demonstrate that doxycycline is superior to azithromycin for the treatment of rectal CT.

Approximately 20% of the study participants had a negative NAAT repeated at the enrollment visit after a recent positive NAAT in clinical care. This could be due to participants receiving antibiotics outside of the study, false-positive tests in the clinic or false-negative tests at study entry, or spontaneous clearance. In the absence of treatment, rectal CT infection can last for weeks to months, but the duration of infection varies widely between individuals [20]. The natural history of CT infection is not well understood and is an important topic for future research.

The mechanism of azithromycin treatment failure in rectal CT is not known but is not likely due to antibiotic resistance, inadequate tissue penetration of the drug, or the prevalence of LGV biovars. Azithromycin resistance among CT has never been conclusively demonstrated, and 1 prior report of resistance was refuted with additional laboratory testing [21]. A pharmacokinetic study demonstrated that drug concentrations of azithromycin in rectal tissue after a single azithromycin dose remain above the minimum inhibitory concentration for CT for at least 14 days [10]. Animal studies have also shown that azithromycin is ineffective in treating gastrointestinal CT infections, even though it is effective for genital infections, despite comparable drug levels in both anatomic tracts [22]. Our finding that LGV-biovar CT was uncommon in the study population and that azithromycin was substantially less effective than doxycycline for the treatment of non–LGV-biovar CT infections refutes the idea that LGV-biovar infections account for the inadequacy of azithromycin.

Different host–microbe interactions in the rectal environment than in the genital tract may alter the effect of azithromycin on CT. The pattern of NAAT clearance we observed with azithromycin was the opposite of that expected with progressive bacterial clearance. This is consistent with, but not proof of, recrudescent infection following a period of transient bacterial latency [23]. The positive-negative-positive pattern could also indicate reinfection, but this would not be expected to differ between arms in a placebo-blinded RCT nor do our behavioral data suggest differential reinfection.

One reason that many clinicians prefer to use azithromycin for CT treatment is concern about inadequate patient adherence to a week-long doxycycline regimen. Our study did not yield sufficient data to examine the impact of adherence, in part because we used generous parameters to define sufficient adherence, but this concern should not be a barrier to using doxycycline in practice. It is unlikely that imperfect adherence in a typical clinic population would negate the difference in effectiveness between the 2 treatments. Moreover, some evidence suggests that doxycycline is effective even with imperfect adherence and at lower doses than typically used in the treatment of genitourinary CT infections [24, 25].

The limitations of our study include the number of participants with LGV-biovar infections, which was too small to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of either regimen for the treatment of LGV-biovar CT. Our study population was almost entirely cisgender male, and the relevance of our findings for transgender people and women with rectal CT is uncertain. We studied only 2 regimens and were thus unable to judge the impact of alternate dosing of azithromycin, such as the weekly 3-dose regimen recommended by the World Health Organization for the treatment of LGV [26].

In summary, this study demonstrated that a 7-day course of doxycycline is substantially more effective than single-dose azithromycin for the treatment of rectal CT. Azithromycin performed so poorly that, even in the context of expected imperfect adherence in real-world use, doxycycline should be the recommended treatment for rectal CT in MSM.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the individuals who participated in this study and the study staff who contributed to it. The authors specifically acknowledge Melinda Tibbals at the National Institutes of Health; Angela LeClair, Rushlenne Pascual, Tamara Bass, Laura Rishel, and Jennifer Morgan at the University of Washington; Mo Drucker and Valerie Rugulo at Fenway Health; Martine Policard, Aditi Sharma, Keven Huang, Logan Richlak, and Bruno Dos Santos at Emmes; Ginger Pittman and Linda McNeil at FHI 360; Drs Jeanne Marrazzo and Edward Hook at the University of Alabama, Birmingham (UAB); the scientific review committee members of the UAB Sexually Transmitted Infections Clinical Trials Group; Dr Timothy Menza, currently with the Oregon State Department of Health; and the San Francisco Department of Public Health Laboratory for technical assistance.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases contract HHSN272201300014I, protocol 17–0092).

Potential conflicts of interest. O. O. S. has participated in research supported by grants to the University of Washington from Hologic, Inc, and SpeeDx, Inc. J. C. D. has participated in research funded by grants to the University of Washington from Hologic, Inc. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References