-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lindley A Barbee, Olusegun O Soge, Christine M Khosropour, Micaela Haglund, Winnie Yeung, James Hughes, Matthew R Golden, The Duration of Pharyngeal Gonorrhea: A Natural History Study, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 73, Issue 4, 15 August 2021, Pages 575–582, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab071

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pharyngeal gonorrhea is relatively common. However, the duration of untreated pharyngeal gonorrhea is unknown.

From March 2016 to December 2018, we enrolled 140 men who have sex with men in a 48-week cohort study. Participants self-collected pharyngeal specimens and completed a survey weekly. Specimens were tested using a nucleic acid amplification test at the conclusion of the study. We estimated the incidence and duration of infection. We defined incident infections as 2 consecutive positive tests, and clearance as 2 consecutive negative tests; and, after visual inspection of the data, we reclassified up to 2 weeks of missing or negative tests as positive if they occurred between 2 episodes of infections. We used Kaplan-Meier estimates to define duration of infection. Finally, we report on the frequency of single-positive tests and the time between the last negative test and the positive test.

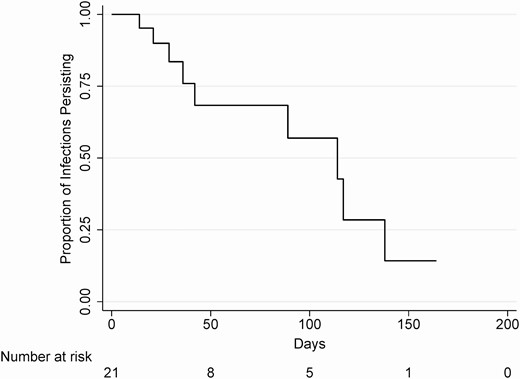

Nineteen (13.6%) of 140 participants experienced 21 pharyngeal infections (incidence, 31.7/100 person-years; 95% confidence interval, 20.7–48.6/100 person-years). The estimated median duration of pharyngeal gonorrhea was 16.3 weeks (95% confidence interval, 5.1–19.7 weeks). Twenty-two men had 25 single-positive specimens, a median of 7 days (interquartile range, 7–10 days) after their last negative test.

The median duration of untreated pharyngeal gonorrhea is 16 weeks, more than double previous estimates. This long duration of infection likely contributes to high levels of gonorrhea transmission.

(See the Editorial Commentary by Adamson and Klausner on pages 583–5.)

Gonorrhea cases in the United States increased >60% between 2014 and 2018 [1]. Some have theorized that Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the pharynx serves as a reservoir, allowing for sustained community transmission [2–5]. To date, the theory of the pharyngeal reservoir has been primarily based on the infection’s commonality. Among men who have sex with men (MSM), >10% have positive screening results [6], and the limited data suggest that this proportion is 2%-10% for women and heterosexual men [6, 7], yet among heterosexual male and female contacts for gonorrhea, 20%–50% have positive results at throat testing [8]. However, the extent to which gonococcal infection at the pharynx sustains population-level transmission is dependent not only on its prevalence but also on the duration of infection, a basic epidemiologic parameter needed to define the reproductive number [9].

To date, 3 studies have attempted to define the duration of pharyngeal gonorrhea, each with significant limitations. Two studies conducted in the 1970s assessed the time from detection of infection to resolution using gonococcal culture and estimated that pharyngeal infections are typically transient, with a median duration of 1–6 weeks [10, 11]. However, their study design is subject to competing biases, since the period from infection to diagnosis is ignored, and cross-sectional enrollment at time of diagnosis tends to oversample long-duration infections (ie, length-time bias) [12]. These problems are compounded by the low sensitivity of cultures in identifying pharyngeal gonorrhea [13]. The third study exploited the epidemiologic principal that the duration of an infection should equal the prevalence divided by incidence, and suggested that the duration is closer to 4 months [14]. We aimed to define the true duration of pharyngeal gonococcal infection—from acquisition to clearance—using highly sensitive nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) [15] to serially test a cohort of MSM.

METHODS

Study Design

The ExGen Study was a prospective, longitudinal cohort study designed to determine the incidence and duration of extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydial infection among MSM. Enrollment and data collection occurred between 25 March 2016 and 31 December 2018. This study was approved by the University of Washington’s Institutional Review Board (no. 50028).

Study Population and Recruitment

The study enrolled MSM aged ≥18 years who were fluent in English, and recruited participants from the Public Health–Seattle & King County (PHSKC) Sexual Health Clinic (SHC), and the University of Washington’s Center for AIDS Research registry of persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Eligibility criteria included report of receptive anal intercourse in the last 12 months, performing oral sex in the past 2 months, and ≥1 of the following in the past 12 months: (1) diagnosis of gonorrhea, chlamydia, or syphilis; (2) use of methamphetamine or amyl nitrate (“poppers”); or( 3) >2 sexual partners in the past 2 months or >5 within ≤12 months. We excluded men who did not have weekly access to the internet, as well as men who the recruiters believed could not complete 12 months of weekly study procedures. All enrolled men completed a written informed consent.

Study Procedures

This prospective study consisted of an enrollment visit, 48 weekly specimens and surveys, and an exit visit. At the enrollment visit, participants underwent face-to-face interview to collect demographic and clinical data, followed by an electronic sexual behavior survey conducted on a computer or participants’ mobile telephone. Unless the participant had documented clinical sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing within 3 weeks of enrollment, all participants were also tested for syphilis, HIV, and rectal and pharyngeal gonorrhea and chlamydia. Study personnel taught participants how to self-collect pharyngeal and rectal specimens using the Aptima universal collection kit, package specimens for shipping, and access the password-protected weekly survey. The study team emphasized that weekly study specimens would not be tested in real time, and that study participation should not supplant participants’ usual routine STI screening. We asked participants to get STI care at PHSKC SHC throughout the study period and requested their consent to access medical records for clinical STI testing and treatment data.

Each week at home, participants collected rectal and pharyngeal swab samples and completed an online survey. Participants who tested positive for gonorrhea or chlamydia at their enrollment visit were asked to wait for 2 (gonorrhea) [16] or 3 (chlamydia) [17] weeks after treatment before beginning weekly specimen and data collection. All other participants began data collection approximately 1 week after their enrollment visit, and we allowed participants to choose the day of the week for personal convenience. Although we requested that participants complete study procedures every 7 days, we allowed up to 3 days beyond the intended collection date for reimbursement purposes and included all returned specimens and surveys in data analyses. Participants received an email or text message each week prompting them to complete the survey. The weekly survey included questions about the participant’s number of new or repeated sex partners, types of sex (eg, insertive or receptive anal, oral-penile, oral-anal, and kissing), number of sex acts, and condom use. The survey included questions regarding adjuvant health behaviors and interval STI testing, treatment, and symptoms.

Participants were instructed to collect pharyngeal and rectal swab samples immediately after completing the study diary and to return specimens to study personnel weekly via US Postal Service. (mailed Aptima specimens for gonorrhea and chlamydia testing have been shown to be stable up to 84 days and in ambient temperatures between 2ºC and 36ºC [18]). On receipt, study personnel placed the specimens in a −80ºC freezer, and specimens were tested after participants completed the study or were classified as lost to follow-up. Specimens were tested in the University of Washington Neisseria Reference Laboratory using the Aptima Combo 2 (Hologic) assay on the fully automated Panther machine (Hologic), according to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments regulatory requirements for quality assurance [19].

At the final in-person study visit, participants completed a final survey, underwent testing for HIV, syphilis, and extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydial infection, and were treated if results were positive. Participants were compensated for their time. In total, participants who completed all study procedures received $630. We further incentivized participation with a lottery of two $500 prizes; participants eligible for the lottery completed >95% of data collection.

Statistical Analyses

Sample Size and Power Calculations

Sample size was calculated using pharyngeal gonorrhea test positivity at the PHSKC SHC in 2013. Based on results of prior studies [10], we hypothesized that pharyngeal gonorrhea could persist for an average of 18 weeks. By varying the number of incident infections and the standard deviation of duration, we determined that 20 incident pharyngeal infections, lasting approximately 18 weeks with a standard deviation of 6 weeks would provide a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 15–20 weeks. We estimated a range of incidences assuming 3–6-month duration of infection, and increased the sample size to account for attrition and right censoring. We estimated that enrolling 140 MSM for a period of 48 weeks would provide the necessary 20 incident pharyngeal gonococcal infections.

Infection Definitions

We defined an incident infection as ≥2 consecutive weeks of pharyngeal specimens positive for N. gonorrhoeae by Aptima Combo 2, and defined clearance as ≥2 weeks of consecutively negative test results. We imputed single weeks of missing and equivocal results if the surrounding weeks’ results were concordant. That is, we considered a single missing or equivocal test to be positive if results in the week immediately before and after were both positive. After visual inspection of the results (Figure 1), we imputed up to 2 weeks of missing or negative results as positive if they occurred between 2 sets of infections (ie, participants 49, 64 and 78). We excluded infections present at enrollment.

Weekly self-obtained pharyngeal gonorrhea nucleic acid amplification test results, sexual activity, and antibiotic receipt for 19 men with incident pharyngeal gonorrhea over 48 weeks. Abbreviations: GC, gonococcal; ID, participant identification number.

Given the high number of single-positive samples, we also report on the number of these positive test results, and the median time (and interquartile range) between the positive test result and the last negative result. We also calculated the estimated incidence and duration of infection if these single-positive specimens were to be considered “true infections.”

Censoring

Infections were right censored if they were present on the final week of the study, if the participant was lost to follow-up for >2 weeks after the last positive specimen, or if they were treated with an antigonococcal regimen. Antigonococcal antibiotics included a third-generation cephalosporin (ie, ceftriaxone, cefixime, or cefpodoxime), azithromycin, or doxycycline. We did not consider penicillins or fluoroquinolones to be effective against gonococcus, given high rates of resistance to these drug [20]. Given uncertainties about time to clearance with treatment and inherent limitations of weekly testing, we considered an infection to have resolved due to treatment (ie, censored) if treatment occurred in the final or penultimate week of infection, or in the week after the last week of positive specimens.

Analyses

We calculated time in days, using calendar time from reported date of specimen collection with enrollment date as time zero; we converted days to weeks for reporting. We calculated the incidence of pharyngeal gonococcal infection as the number of new infections divided by the time at risk of infection (ie, weeks of negative NAAT results), and used Kaplan-Meier estimates to calculate the duration of infection. We used log-rank tests to assess for differences in duration of infection by HIV status, history of gonorrhea in the past 12 months, coinfection with chlamydia at the pharynx, and smoking status. We used logistic regression with the cluster function to assess association between sore throat and pharyngeal infection. All data were collected and managed through REDCap [21]. We used Stata15 software (StataCorp) for all statistical analyses, and considered differences to be significant at P < .05.

RESULTS

Study Population

Between March 2016 and December 2018 we enrolled 140 MSM with a mean age of 37 years (range, 20–75 years); 71 (51%) were HIV infected (Table 1). Most (74.3%) had had gonorrhea, chlamydia or syphilis diagnosed in the past year, and 37 (26.4%) had a bacterial STI diagnosed at enrollment. Of the 140 men enrolled, 28 (20%) did not complete any at-home study procedures. Excluding these men, the median follow-up time for 112 men was 39 weeks; 37 (26%) men completed 1–10 weeks, 19 (14%) completed 16–39 weeks, and 56 (40%) completed ≥40 weeks of study procedures. Enrolled men contributed a total of 70.5 person-years of follow-up.

Study Population Demographics, Sexual Behavior, and Sexually Transmitted Infection History and Diagnoses at Enrollment

| . | Study Participants, No. (%)a . | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | All Participants (N = 140) . | Participants With ≥1 Incident Pharyngeal GC Infection (n = 19) . |

| Age, mean (range), y . | 37 (20–75) . | 35 (21–54) . |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 88 (63) | 13 (68) |

| Non-Hispanic black/African American | 15 (11) | 0 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 25 (18) | 5 (26) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 8 (5.7) | 1 (5.3) |

| Other | 3 (2.5) | 0 |

| Annual income | ||

| <$14 999 | 54 (39) | 7 (37) |

| >$15 000–$29 999 | 26 (19) | 7 (37) |

| >$30 000–$49 999 | 28 (20) | 2 (11) |

| >$50 000–$99 999 | 25 (18) | 2 (11) |

| >$100 000 | 7 (5.0) | 1 (5.3) |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Grade school | 3 (2.1) | 0 |

| High school | 30 (21) | 6 (32) |

| Some college/associate or technical degree | 50 (36) | 7 (39) |

| Bachelor’s degree/some graduate school | 39 (28) | 5 (28) |

| Graduate degree | 18 (13) | 1 (6) |

| HIV infected | 71 (51) | 11 (58) |

| Self-reported lifetime STI history | ||

| Syphilis | 66 (47) | 9 (47) |

| Gonorrhea | 104 (74) | 18 (95) |

| Chlamydia | 95 (68) | 15 (79) |

| Herpes | 31 (22) | 6 (32) |

| Criteria for study entry | ||

| Bacterial STI diagnosis within past 12 mo | 104 (74) | 15 (79) |

| Methamphetamine or amyl nitrate use | 35 (25) | 3 (17) |

| No. of sexual partners | 117 (84) | 18 (95) |

| Early syphilis diagnosis at enrollment | 5 (4) | 2 (11) |

| HIV diagnosis at enrollment | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Gonorrhea diagnosis at enrollment | 19 (14) | 3 (16) |

| Pharyngeal | 11 (8) | 1 (5) |

| Rectal | 13 (9) | 2 (11) |

| Urethral | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Chlamydia diagnosis at enrollment | 17 (11) | 4 (21) |

| Pharyngeal | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Rectal | 14 (9) | 4 (22) |

| Urethral | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Sexual activity within past 2 mo | ||

| Sexual partners, median (IQR), no. | 6 (4–12) | 8.5 (5–15) |

| Oral-penile sex acts, median (IQR), no. | 8 (5–14) | 6 (4–9) |

| Oral-anal sex performed | 82 (77) | 8 (44) |

| . | Study Participants, No. (%)a . | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | All Participants (N = 140) . | Participants With ≥1 Incident Pharyngeal GC Infection (n = 19) . |

| Age, mean (range), y . | 37 (20–75) . | 35 (21–54) . |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 88 (63) | 13 (68) |

| Non-Hispanic black/African American | 15 (11) | 0 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 25 (18) | 5 (26) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 8 (5.7) | 1 (5.3) |

| Other | 3 (2.5) | 0 |

| Annual income | ||

| <$14 999 | 54 (39) | 7 (37) |

| >$15 000–$29 999 | 26 (19) | 7 (37) |

| >$30 000–$49 999 | 28 (20) | 2 (11) |

| >$50 000–$99 999 | 25 (18) | 2 (11) |

| >$100 000 | 7 (5.0) | 1 (5.3) |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Grade school | 3 (2.1) | 0 |

| High school | 30 (21) | 6 (32) |

| Some college/associate or technical degree | 50 (36) | 7 (39) |

| Bachelor’s degree/some graduate school | 39 (28) | 5 (28) |

| Graduate degree | 18 (13) | 1 (6) |

| HIV infected | 71 (51) | 11 (58) |

| Self-reported lifetime STI history | ||

| Syphilis | 66 (47) | 9 (47) |

| Gonorrhea | 104 (74) | 18 (95) |

| Chlamydia | 95 (68) | 15 (79) |

| Herpes | 31 (22) | 6 (32) |

| Criteria for study entry | ||

| Bacterial STI diagnosis within past 12 mo | 104 (74) | 15 (79) |

| Methamphetamine or amyl nitrate use | 35 (25) | 3 (17) |

| No. of sexual partners | 117 (84) | 18 (95) |

| Early syphilis diagnosis at enrollment | 5 (4) | 2 (11) |

| HIV diagnosis at enrollment | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Gonorrhea diagnosis at enrollment | 19 (14) | 3 (16) |

| Pharyngeal | 11 (8) | 1 (5) |

| Rectal | 13 (9) | 2 (11) |

| Urethral | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Chlamydia diagnosis at enrollment | 17 (11) | 4 (21) |

| Pharyngeal | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Rectal | 14 (9) | 4 (22) |

| Urethral | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Sexual activity within past 2 mo | ||

| Sexual partners, median (IQR), no. | 6 (4–12) | 8.5 (5–15) |

| Oral-penile sex acts, median (IQR), no. | 8 (5–14) | 6 (4–9) |

| Oral-anal sex performed | 82 (77) | 8 (44) |

Abbreviations: GC, gonococcal; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

aData represent no. (%) of participants unless otherwise specified.

Study Population Demographics, Sexual Behavior, and Sexually Transmitted Infection History and Diagnoses at Enrollment

| . | Study Participants, No. (%)a . | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | All Participants (N = 140) . | Participants With ≥1 Incident Pharyngeal GC Infection (n = 19) . |

| Age, mean (range), y . | 37 (20–75) . | 35 (21–54) . |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 88 (63) | 13 (68) |

| Non-Hispanic black/African American | 15 (11) | 0 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 25 (18) | 5 (26) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 8 (5.7) | 1 (5.3) |

| Other | 3 (2.5) | 0 |

| Annual income | ||

| <$14 999 | 54 (39) | 7 (37) |

| >$15 000–$29 999 | 26 (19) | 7 (37) |

| >$30 000–$49 999 | 28 (20) | 2 (11) |

| >$50 000–$99 999 | 25 (18) | 2 (11) |

| >$100 000 | 7 (5.0) | 1 (5.3) |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Grade school | 3 (2.1) | 0 |

| High school | 30 (21) | 6 (32) |

| Some college/associate or technical degree | 50 (36) | 7 (39) |

| Bachelor’s degree/some graduate school | 39 (28) | 5 (28) |

| Graduate degree | 18 (13) | 1 (6) |

| HIV infected | 71 (51) | 11 (58) |

| Self-reported lifetime STI history | ||

| Syphilis | 66 (47) | 9 (47) |

| Gonorrhea | 104 (74) | 18 (95) |

| Chlamydia | 95 (68) | 15 (79) |

| Herpes | 31 (22) | 6 (32) |

| Criteria for study entry | ||

| Bacterial STI diagnosis within past 12 mo | 104 (74) | 15 (79) |

| Methamphetamine or amyl nitrate use | 35 (25) | 3 (17) |

| No. of sexual partners | 117 (84) | 18 (95) |

| Early syphilis diagnosis at enrollment | 5 (4) | 2 (11) |

| HIV diagnosis at enrollment | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Gonorrhea diagnosis at enrollment | 19 (14) | 3 (16) |

| Pharyngeal | 11 (8) | 1 (5) |

| Rectal | 13 (9) | 2 (11) |

| Urethral | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Chlamydia diagnosis at enrollment | 17 (11) | 4 (21) |

| Pharyngeal | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Rectal | 14 (9) | 4 (22) |

| Urethral | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Sexual activity within past 2 mo | ||

| Sexual partners, median (IQR), no. | 6 (4–12) | 8.5 (5–15) |

| Oral-penile sex acts, median (IQR), no. | 8 (5–14) | 6 (4–9) |

| Oral-anal sex performed | 82 (77) | 8 (44) |

| . | Study Participants, No. (%)a . | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | All Participants (N = 140) . | Participants With ≥1 Incident Pharyngeal GC Infection (n = 19) . |

| Age, mean (range), y . | 37 (20–75) . | 35 (21–54) . |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 88 (63) | 13 (68) |

| Non-Hispanic black/African American | 15 (11) | 0 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 25 (18) | 5 (26) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 8 (5.7) | 1 (5.3) |

| Other | 3 (2.5) | 0 |

| Annual income | ||

| <$14 999 | 54 (39) | 7 (37) |

| >$15 000–$29 999 | 26 (19) | 7 (37) |

| >$30 000–$49 999 | 28 (20) | 2 (11) |

| >$50 000–$99 999 | 25 (18) | 2 (11) |

| >$100 000 | 7 (5.0) | 1 (5.3) |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Grade school | 3 (2.1) | 0 |

| High school | 30 (21) | 6 (32) |

| Some college/associate or technical degree | 50 (36) | 7 (39) |

| Bachelor’s degree/some graduate school | 39 (28) | 5 (28) |

| Graduate degree | 18 (13) | 1 (6) |

| HIV infected | 71 (51) | 11 (58) |

| Self-reported lifetime STI history | ||

| Syphilis | 66 (47) | 9 (47) |

| Gonorrhea | 104 (74) | 18 (95) |

| Chlamydia | 95 (68) | 15 (79) |

| Herpes | 31 (22) | 6 (32) |

| Criteria for study entry | ||

| Bacterial STI diagnosis within past 12 mo | 104 (74) | 15 (79) |

| Methamphetamine or amyl nitrate use | 35 (25) | 3 (17) |

| No. of sexual partners | 117 (84) | 18 (95) |

| Early syphilis diagnosis at enrollment | 5 (4) | 2 (11) |

| HIV diagnosis at enrollment | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Gonorrhea diagnosis at enrollment | 19 (14) | 3 (16) |

| Pharyngeal | 11 (8) | 1 (5) |

| Rectal | 13 (9) | 2 (11) |

| Urethral | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Chlamydia diagnosis at enrollment | 17 (11) | 4 (21) |

| Pharyngeal | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Rectal | 14 (9) | 4 (22) |

| Urethral | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Sexual activity within past 2 mo | ||

| Sexual partners, median (IQR), no. | 6 (4–12) | 8.5 (5–15) |

| Oral-penile sex acts, median (IQR), no. | 8 (5–14) | 6 (4–9) |

| Oral-anal sex performed | 82 (77) | 8 (44) |

Abbreviations: GC, gonococcal; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

aData represent no. (%) of participants unless otherwise specified.

Incidence of Pharyngeal Gonorrhea

In 19 men, 21 pharyngeal gonorrhea infections developed, which corresponded to an incidence of 31.7/100 person-years (95% CI: 20.7–48.6/100 person-years). In addition, 22 men had 25 single-positive specimens. Assuming that these single-positive specimens are “true infections,” they would increase the incidence to 55.2/100 person-years.

Duration of Pharyngeal Gonococcal Infection

Infections were censored primarily for treatment (83%), followed by loss to follow-up (8.3%), and end of study (8.3%). The estimated median duration of untreated pharyngeal gonorrhea was 16.3 weeks (95% CI: 5.1–19.7 weeks) (Figure 2). The duration of infection did not significantly vary based on HIV status, recent history of gonorrhea, concurrent pharyngeal chlamydial infection, or smoking status. The 25 single-positive specimens occurred a median of 7 days after a negative test (interquartile range, 7–10 days). Including these positive specimens as true infections decreased the duration of infection to 10 weeks (95% CI: 4–19.7 weeks).

Kaplan-Meier survival estimate for the duration of pharyngeal gonorrhea infection.

Symptoms and Patterns of Sexual Behavior

Men reported a sore throat during the first or second week of infection in 6 (26%) of the cases. While sore throat was not associated with positive NAAT results for gonorrhea (P = .29), report of a sore throat was associated with the first or second week of an infection (odds ratio, 2.6; P = .03).

Most men with diagnoses of pharyngeal gonorrhea engaged in kissing, oral-penile, oral-anal sex, or some combination of those behaviors in the week before or the week of (ie, exposure period) their incident infection (Figure 1). However, 3 infections (15%) occurred in participants who reported kissing or oral-anal sex as their only oral exposures in the exposure period (Figure 1; participants 49 and 123, twice). Among the 25 single-positive tests, the majority (68%) occurred within the context of an oral-penile sexual exposure. Four (16%) specimens were positive during the week of or the week following a kissing or oral-anal sexual exposure. Another 4 single-positive specimens occurred in the absence of any reported oral sexual exposure.

DISCUSSION

This is one of very few studies on the natural history of pharyngeal gonorrhea. Using a prospective study design, we determined that infection persists for a median of 16 weeks, a finding that supports the hypothesis that pharyngeal infections may play an important role in sustaining high levels of gonorrhea transmission [2]. We also found that 15% of pharyngeal infections occurred in men who denied recent oral-penile exposures, suggesting that transmission to the pharynx likely can occur through exposures other than fellatio—namely, kissing and oral-anal sex—also supporting the theory that pharyngeal gonorrhea may serve as a reservoir for the gonorrhea epidemic.

Our findings differ from prior, empiric efforts to measure the duration of pharyngeal gonococcal infections [10, 11] but agree with an estimate derived from measures of incidence and prevalence [14]. Prior empiric studies sampled prevalent infections and followed them until they became culture negative, an approach prone to oversampling long-duration infections (length-time bias) [12] while neglecting the period of infection before diagnosis. Moreover, these studies, conducted in the 1970s, relied on culture, which is insensitive in detecting N. gonorrhoeae in the throat [13, 15]. Our study used NAAT—a diagnostic test significantly more sensitive than culture [22]—and more than doubled the previous estimate of the median duration of pharyngeal gonorrhea of 6 weeks [10]. Interestingly, our estimate of 16.3 weeks nearly precisely matches the calculation reported by Chow and colleagues [14], who used prevalence and incidence data (114–137 days).

Neither culture nor NAAT perfectly define infection status. Although molecular tests enhance the detection of N. gonorrhoeae compared to culture, NAAT may lead to false-positives as nonviable organism may yield a positive test. This conundrum may occur after treatment [16], a recent sexual encounter, or from a contaminated environment [23]. We identified 4 single-positive NAAT results that occurred in the absence of kissing or sex, suggesting that transmission occurs through nonsexual means, that participants misreported sexual activity, or that these false-positive tests resulted from environmental contamination. While the NAAT’s lack of specificity may have caused us to overestimate duration and incidence, we believe that the risk of overestimation is likely small compared with the poor sensitivity of N. gonorrhoeae culture, particularly at the pharynx. The gonococcus is a fastidious organism, and the oropharynx is a polymicrobial environment. Even in the most experienced laboratories, culture is only about 30%–50% sensitive for detecting the bacterium at the throat [13, 24].

These data help inform a recent debate in the field of STIs. Fairley and colleagues have proposed that the oropharynx is the source of most (70%) [2] gonococcal infections in MSM [25], reasoning that the mouth’s role in multiple sexual activities, the common use of saliva as lubricant, and the high prevalence of infection at the oropharynx explain the high incidence of gonorrhea at diverse anatomic sites among MSM. They offer this theory as a counterfactual to the idea that the urethra sustains epidemic levels of gonorrhea among MSM. Gonococcal urethritis exhibits a short duration of infection—usually less than a week—and a low prevalence. Models suggest that despite the high transmissibility of gonococcal urethritis [26], if the urethra were the sole source of pharyngeal infection, MSM would have to have >100 sex partners per year to result in the gonorrhea incidence that is currently observed [25].

Other authorities have expressed skepticism about the role of the oropharynx in gonococcal transmission [27], highlighting the paucity of empiric data to support the theory that the pharynx is a critical source of transmission, evidence that saliva likely inhibits the transmission of viable bacteria [28], and previously published data suggesting that the duration of pharyngeal infection is brief [10, 11]. Our data suggest that pharyngeal N. gonorrhoeae often persists for a relatively long period of time, especially compared with urethral infection [29], and that 15% of pharyngeal infections could be transmitted through sexual exposures other than fellatio. While these observations do not definitively establish an important role for the pharynx as a major source of gonorrhea transmission, they support the plausibility of such a role.

We were surprised with the association of symptoms at the beginning of an infection, but not with any positive pharyngeal NAAT results. Nearly 25% of men experienced a sore throat during the first or second week of their infection, which is higher than previous estimates that <10% [30] of infections are symptomatic. We suspect that at the time of acquisition, in some hosts the throat becomes inflamed, and the inflammation is significant enough to produce pain. We postulate that, over time, inflammation subsides as the gonococcus takes up residence in the throat. This finding implores additional inquiry to understanding the pathobiology of N. gonorrhoeae in the oropharynx.

Strengths of our study include its prospective cohort design, the use of serial NAATs to identify infections, and the integration of biological and behavioral data. Our study also has important limitations. First, study participants frequently underwent clinical STI testing leading to diagnosis and treatment, which required us to censor a large number of infections rather than observe their total duration in the absence of treatment. This resulted in estimates with relatively wide confidence intervals. Second, the study relied on NAAT positivity to define the presence or absence of infection, which may have overestimated either the number or the duration of infections. Finally, our assessment of sexual behaviors associated with transmission relies on self-reported data, which are subject to recall bias. We attempted to mitigate this risk by using a weekly survey to diminish the time between sexual act and the record.

In conclusion, our data confirm that the median duration of pharyngeal gonorrhea is considerably longer than previously believed, over 16 weeks. At the same time, this study raises a number of questions that deserve further investigation. Fifteen percent of cases ostensibly occurred through transmission mechanisms other than oral-penile sex, a fact that could have significant implications for gonorrhea prevention and control, not only for MSM but also for heterosexuals. In addition, the fact that nearly one-quarter of cases reported a sore throat in the first or second week of infection, but not throughout infection, begs for an enhanced understanding of the pathobiology of and immune response to the presence of gonococcus in the oropharynx.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We would like to thank our study participants, and the Public Health–Seattle & King County Sexual Health Clinic for donating study space. We thank Rushlenne Pascual and Daphne Hamilton from the University of Washington Neisseria Reference Laboratory for laboratory support.

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant K23 AI113185 to L. A. B.); Hologic (provision of specimen collection kits and test reagents); the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH; grant UL1 TR002319 to REDCap, data collection and management system at the University of Washington’s Institute for Translation Health Sciences); and the University of Washington/Fred Hutch Center for AIDS Research, which is funded by the NIH (grant AI027757) and the following NIH institutes: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute on Aging, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Potential conflicts of interests. L. A. B., O. O. S., C. M. K., and M. R. G. report research support from Hologic. L. A. B. and O. O. S. have received research support from SpeeDX, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts. The authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Presented in part: International Society for STD Research World Congress, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, July 15, 2019.