-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tami H Skoff, Amanda E Faulkner, Jennifer L Liang, Meghan Barnes, Kathy Kudish, Ebony Thomas, Cynthia Kenyon, Marisa Hoffman, Eva Pradhan, Juventila Liko, Susan Hariri, Pertussis Infections Among Pregnant Women in the United States, 2012–2017, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 73, Issue 11, 1 December 2021, Pages e3836–e3841, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1112

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Little is known about pertussis among pregnant women, a population at increased risk for severe morbidity from respiratory infections such as influenza. We used the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Enhanced Pertussis Surveillance (EPS) system to describe pertussis epidemiology among pregnant and nonpregnant women of childbearing age.

Pertussis cases in women aged 18–44 years with cough onset between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2017 were identified in 7 EPS states. Surveillance data were collected through patient and provider interviews and immunization registries. Bridged-race, intercensal population data and live birth estimates were used as denominators.

We identified 1582 pertussis cases among women aged 18–44 years; 5.1% (76/1499) of patients with a known pregnancy status were pregnant at cough onset. Of the pregnant patients with complete information, 81.7% (49/60) reported onset during the second or third trimester. The median ages of pregnant and nonpregnant patients were 29.0 and 33.0 years, respectively. Most pregnant and nonpregnant patients were White (78.3% vs. 86.4%, respectively; P = .09) and non-Hispanic (72.6% vs. 77.3%, respectively; P = .35). The average annual incidence of pertussis was 7.7/100000 among pregnancy women and 7/3/100000 among nonpregnant women. Compared to nonpregnant patients, more pregnant patients reported whoop (41.9% vs. 31.3%, respectively), posttussive vomiting (58.1% vs. 47.9%, respectively), and apnea (37.3% vs. 29.0%, respectively); however, these differences were not statistically significant (P values > .05 for all). A similar proportion of pregnant and nonpregnant patients reported ever having received Tdap (tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine; 31.6% vs. 32.7%, respectively; P = .84).

Our analysis suggests that incidence of pertussis and clinical characteristics of disease are similar among pregnant and nonpregnant women. Continued monitoring is important to further define pertussis epidemiology in pregnant women.

Pertussis is a highly contagious, bacterial respiratory disease. Despite being vaccine-preventable, the number of reported cases has been increasing in recent years [1]. While infants are at greatest risk for severe pertussis-related morbidity and mortality, the disease can affect persons of all ages, with potentially debilitating complications including fractured ribs, pneumothorax, and aspiration pneumonia in adolescents and adults [2–4]. Classic symptoms of pertussis infection include paroxysmal cough, posttussive vomiting, and “whoop”; however, the symptoms of pertussis can vary widely, ranging from a mild cough illness to severe respiratory infection with classic symptomology, and can be modified by factors such as pertussis vaccination status and recent antibiotic use.

Currently in the United States, a 5-dose pertussis vaccination series is recommended for children between the ages of 2 months and 6 years, followed by an adolescent booster of Tdap (tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis) at age 11–12 years. In 2011, maternal Tdap vaccination during pregnancy was introduced as a strategy to protect newborn infants through the transfer of maternal antipertussis antibodies [5]. While the main goal of maternal immunization during pregnancy is to provide protection to the young infant, vaccinating during pregnancy also has the added benefit of providing direct protection to the mother.

Pregnancy has been identified as a risk factor for illness, complications, and death from respiratory infections such as influenza [6]. This increased risk is thought to be due not only to physiologic changes that occur during pregnancy [7], such as decreased lung capacity and increased heart rate and oxygen consumption, but also to changes in the immune system [8]. Influenza during pregnancy also increases a woman’s risk of pregnancy-related complications, including pregnancy loss and preterm labor [9]. While numerous studies have highlighted the clinical symptoms and risks of influenza infection among pregnant women, to date only a limited number of case reports of pertussis in pregnant women have described the clinical symptoms associated with infection [10–12]. Whether pregnant women are at increased risk for severe illness due to pertussis infection is not known. Additionally, it is unclear how the burden of pertussis among pregnant women compares to the burden of pertussis among nonpregnant women of childbearing age.

To determine the incidence and characteristics of pertussis infection in pregnant women, we conducted a descriptive analysis of pertussis data collected through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Emerging Infections Program Network/Enhanced Pertussis Surveillance system, and compared the clinical and epidemiologic features of pertussis infection between pregnant and nonpregnant women of childbearing age.

METHODS

Female pertussis patients of childbearing age (18 through 44 years) with cough onset between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2017 were included in the analysis. Pertussis cases were identified through enhanced surveillance in 7 Enhanced Pertussis Surveillance sites (Colorado: 5-county Denver area; Connecticut: statewide; Georgia: 8-county Atlanta area [2014–2017 only]; Minnesota: statewide; New Mexico: statewide; New York: 15-county Rochester/Albany area; and Oregon: 3-county Portland area). Cases were classified according to the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists’ definition for probable or confirmed pertussis. A probable case was defined as a cough illness lasting ≥2 weeks and at least 1 clinical symptom (paroxysms, inspiratory whoop, or posttussive vomiting); a confirmed case was defined as either (1) a probable case with a positive polymerase chain reaction result or epidemiologic linkage to a laboratory-confirmed case; or (2) a cough of any duration with the isolation of Bordetella pertussis [13].

Surveillance personnel completed a standardized case report form through patient and provider interviews to collect demographics, clinical presentation, epidemiologic information, and pregnancy status at the time of cough onset, including completed weeks of gestation and/or expected due date; for all hospitalized patients, medical records were reviewed. The trimester of pregnancy was calculated based on the completed weeks of gestation at the time of cough onset or expected due date, and was defined as first trimester (0–13 weeks gestation), second trimester (14–27 weeks gestation), or third trimester (28–42 weeks gestation). For pregnant patients with cough onset during the third trimester of pregnancy or with an unknown trimester of cough onset, surveillance data were reviewed to determine whether any infants born to pregnant pertussis patients were among reported pertussis cases. When a pertussis case was identified in an infant, information was collected on the source of infant infection, defined as a person with cough illness consistent with pertussis who had contact with the infant case-patient in the 7- to 20-day period before the date of infant cough onset. If more than 1 potential source was identified, the person with the earliest cough onset date was selected. Tdap vaccination history (all Tdap doses, not just those received during pregnancy) was collected through patient and provider interviews and a review of state immunization records; nonreceipt of Tdap was not confirmed.

Incidence of pertussis for pregnant and nonpregnant women were calculated as cases per 100 000 population; 2017 bridged-race, intercensal population data and live birth estimates from the National Center for Health Statistics were used as denominators. Live birth data were used to estimate the total number of pregnant women for the defined surveillance areas; live birth denominators were subtracted from overall National Center for Health Statistics population estimates to obtain the population of nonpregnant women in the surveillance area. Proportions were calculated out of those with a known response and were compared using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests; differences in medians and means were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and t-test, respectively. P values of < .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

This evaluation was deemed public health practice and designated as nonresearch by the CDC Human Research Protection Office; therefore, it did not require a full review by the CDC Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

A total of 1582 pertussis cases were reported among women aged 18–44 years; 5.1% (76/1499) of patients with a known pregnancy status were pregnant at the time of cough onset. The median ages were 33 years among nonpregnant patients and 29 years among pregnant patients (Table 1). A similar proportion of pregnant and nonpregnant patients were White (78.3% and 86.4%, respectively) and of Hispanic ethnicity (27.4% and 22.7%, respectively). By state, the proportion of cases in pregnant women ranged from 0% in Georgia to 6.8% in New Mexico.

Selected Characteristics of Female Pertussis Patients aged 18–44 years by Pregnancy Status, 2012–2017

| . | Pregnant Patients, n = 76 . | Nonpregnant Patients, n = 1423 . | Total Cases, n = 1499 . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (range) [IQR] | 29 (18–43) [10] | 33 (18–44) [15] | 32 (18–44) [15] | .03 |

| Racea | ||||

| White | 54 (78.3%) | 1137 (86.4%) | 1191 (86.0%) | .09 |

| Black | 4 (5.8%) | 69 (5.2%) | 73 (5.3%) | |

| Other | 11 (15.9%) | 110 (8.4%) | 121 (8.7%) | |

| Ethnicitya | ||||

| Hispanic | 20 (27.4%) | 306 (22.7%) | 326 (23.0%) | .35 |

| Non-Hispanic | 53 (72.6%) | 1041 (77.3%) | 1094 (77.0%) | |

| EPS site | ||||

| Colorado | 15 (19.7%) | 266 (18.7%) | 281 (18.7%) | .45 |

| Connecticut | 2 (2.6%) | 44 (3.1%) | 46 (3.1%) | |

| Georgia | 0 (0%) | 35 (2.4%) | 35 (2.3%) | |

| Minnesota | 25 (32.9%) | 592 (41.6%) | 617 (41.2%) | |

| New Mexico | 23 (30.3%) | 314 (22.1%) | 337 (22.5%) | |

| New York | 4 (5.3%) | 60 (4.2%) | 64 (4.3%) | |

| Oregon | 7 (9.2%) | 112 (7.9%) | 119 (7.9%) | |

| CSTE pertussis case classification | ||||

| Confirmed | 64 (84.2%) | 1062 (74.6%) | 1126 (75.1%) | .06 |

| Probable | 12 (15.8%) | 361 (25.4%) | 373 (24.9%) | |

| Ever received Tdap | 24 (31.6%) | 465 (32.7%) | 489 (32.6%) | .84 |

| Time since last Tdapb | ||||

| <2 years | 10 (41.7%) | 112 (24.1%) | 122 (24.9%) | .05 |

| ≥2 years | 14 (58.3%) | 353 (75.9%) | 367 (75.1%) | |

| Mean number of physician visitsc (range) | 1.6 (0–6) | 1.4 (0–10) | 1.4 (0–10) | .55 |

| Prescribed antibiotics recommended for the treatment of pertussisd | 69 (93.2%) | 1349 (95.0%) | 1418 (94.9%) | .42 |

| . | Pregnant Patients, n = 76 . | Nonpregnant Patients, n = 1423 . | Total Cases, n = 1499 . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (range) [IQR] | 29 (18–43) [10] | 33 (18–44) [15] | 32 (18–44) [15] | .03 |

| Racea | ||||

| White | 54 (78.3%) | 1137 (86.4%) | 1191 (86.0%) | .09 |

| Black | 4 (5.8%) | 69 (5.2%) | 73 (5.3%) | |

| Other | 11 (15.9%) | 110 (8.4%) | 121 (8.7%) | |

| Ethnicitya | ||||

| Hispanic | 20 (27.4%) | 306 (22.7%) | 326 (23.0%) | .35 |

| Non-Hispanic | 53 (72.6%) | 1041 (77.3%) | 1094 (77.0%) | |

| EPS site | ||||

| Colorado | 15 (19.7%) | 266 (18.7%) | 281 (18.7%) | .45 |

| Connecticut | 2 (2.6%) | 44 (3.1%) | 46 (3.1%) | |

| Georgia | 0 (0%) | 35 (2.4%) | 35 (2.3%) | |

| Minnesota | 25 (32.9%) | 592 (41.6%) | 617 (41.2%) | |

| New Mexico | 23 (30.3%) | 314 (22.1%) | 337 (22.5%) | |

| New York | 4 (5.3%) | 60 (4.2%) | 64 (4.3%) | |

| Oregon | 7 (9.2%) | 112 (7.9%) | 119 (7.9%) | |

| CSTE pertussis case classification | ||||

| Confirmed | 64 (84.2%) | 1062 (74.6%) | 1126 (75.1%) | .06 |

| Probable | 12 (15.8%) | 361 (25.4%) | 373 (24.9%) | |

| Ever received Tdap | 24 (31.6%) | 465 (32.7%) | 489 (32.6%) | .84 |

| Time since last Tdapb | ||||

| <2 years | 10 (41.7%) | 112 (24.1%) | 122 (24.9%) | .05 |

| ≥2 years | 14 (58.3%) | 353 (75.9%) | 367 (75.1%) | |

| Mean number of physician visitsc (range) | 1.6 (0–6) | 1.4 (0–10) | 1.4 (0–10) | .55 |

| Prescribed antibiotics recommended for the treatment of pertussisd | 69 (93.2%) | 1349 (95.0%) | 1418 (94.9%) | .42 |

Abbreviations: CSTE, Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; EPS, Enhanced Pertussis Surveillance; IQR, interquartile range.

aCalculated out of those with a known response. For pregnant patients: race (n = 69) and ethnicity (n = 73); for nonpregnant patients: race (n = 1316) and ethnicity (n = 1347); for total: race (n = 1385) and ethnicity (n = 1420).

bCalculated out of total number of patients that ever received Tdap (n = 24 for pregnant patients; n = 465 for nonpregnant patients; n = 489 for total).

cMean number of physician visits between cough onset date and the time of diagnosis. Calculated out of those with a known response. For pregnant patients, n = 75; for nonpregnant patients, n = 1390; for total, n = 1465.

dCalculated out of those with a known response. For pregnant patients, n=74; for nonpregnant patients, n=1420; for total, n=1494.

Selected Characteristics of Female Pertussis Patients aged 18–44 years by Pregnancy Status, 2012–2017

| . | Pregnant Patients, n = 76 . | Nonpregnant Patients, n = 1423 . | Total Cases, n = 1499 . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (range) [IQR] | 29 (18–43) [10] | 33 (18–44) [15] | 32 (18–44) [15] | .03 |

| Racea | ||||

| White | 54 (78.3%) | 1137 (86.4%) | 1191 (86.0%) | .09 |

| Black | 4 (5.8%) | 69 (5.2%) | 73 (5.3%) | |

| Other | 11 (15.9%) | 110 (8.4%) | 121 (8.7%) | |

| Ethnicitya | ||||

| Hispanic | 20 (27.4%) | 306 (22.7%) | 326 (23.0%) | .35 |

| Non-Hispanic | 53 (72.6%) | 1041 (77.3%) | 1094 (77.0%) | |

| EPS site | ||||

| Colorado | 15 (19.7%) | 266 (18.7%) | 281 (18.7%) | .45 |

| Connecticut | 2 (2.6%) | 44 (3.1%) | 46 (3.1%) | |

| Georgia | 0 (0%) | 35 (2.4%) | 35 (2.3%) | |

| Minnesota | 25 (32.9%) | 592 (41.6%) | 617 (41.2%) | |

| New Mexico | 23 (30.3%) | 314 (22.1%) | 337 (22.5%) | |

| New York | 4 (5.3%) | 60 (4.2%) | 64 (4.3%) | |

| Oregon | 7 (9.2%) | 112 (7.9%) | 119 (7.9%) | |

| CSTE pertussis case classification | ||||

| Confirmed | 64 (84.2%) | 1062 (74.6%) | 1126 (75.1%) | .06 |

| Probable | 12 (15.8%) | 361 (25.4%) | 373 (24.9%) | |

| Ever received Tdap | 24 (31.6%) | 465 (32.7%) | 489 (32.6%) | .84 |

| Time since last Tdapb | ||||

| <2 years | 10 (41.7%) | 112 (24.1%) | 122 (24.9%) | .05 |

| ≥2 years | 14 (58.3%) | 353 (75.9%) | 367 (75.1%) | |

| Mean number of physician visitsc (range) | 1.6 (0–6) | 1.4 (0–10) | 1.4 (0–10) | .55 |

| Prescribed antibiotics recommended for the treatment of pertussisd | 69 (93.2%) | 1349 (95.0%) | 1418 (94.9%) | .42 |

| . | Pregnant Patients, n = 76 . | Nonpregnant Patients, n = 1423 . | Total Cases, n = 1499 . | P Value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (range) [IQR] | 29 (18–43) [10] | 33 (18–44) [15] | 32 (18–44) [15] | .03 |

| Racea | ||||

| White | 54 (78.3%) | 1137 (86.4%) | 1191 (86.0%) | .09 |

| Black | 4 (5.8%) | 69 (5.2%) | 73 (5.3%) | |

| Other | 11 (15.9%) | 110 (8.4%) | 121 (8.7%) | |

| Ethnicitya | ||||

| Hispanic | 20 (27.4%) | 306 (22.7%) | 326 (23.0%) | .35 |

| Non-Hispanic | 53 (72.6%) | 1041 (77.3%) | 1094 (77.0%) | |

| EPS site | ||||

| Colorado | 15 (19.7%) | 266 (18.7%) | 281 (18.7%) | .45 |

| Connecticut | 2 (2.6%) | 44 (3.1%) | 46 (3.1%) | |

| Georgia | 0 (0%) | 35 (2.4%) | 35 (2.3%) | |

| Minnesota | 25 (32.9%) | 592 (41.6%) | 617 (41.2%) | |

| New Mexico | 23 (30.3%) | 314 (22.1%) | 337 (22.5%) | |

| New York | 4 (5.3%) | 60 (4.2%) | 64 (4.3%) | |

| Oregon | 7 (9.2%) | 112 (7.9%) | 119 (7.9%) | |

| CSTE pertussis case classification | ||||

| Confirmed | 64 (84.2%) | 1062 (74.6%) | 1126 (75.1%) | .06 |

| Probable | 12 (15.8%) | 361 (25.4%) | 373 (24.9%) | |

| Ever received Tdap | 24 (31.6%) | 465 (32.7%) | 489 (32.6%) | .84 |

| Time since last Tdapb | ||||

| <2 years | 10 (41.7%) | 112 (24.1%) | 122 (24.9%) | .05 |

| ≥2 years | 14 (58.3%) | 353 (75.9%) | 367 (75.1%) | |

| Mean number of physician visitsc (range) | 1.6 (0–6) | 1.4 (0–10) | 1.4 (0–10) | .55 |

| Prescribed antibiotics recommended for the treatment of pertussisd | 69 (93.2%) | 1349 (95.0%) | 1418 (94.9%) | .42 |

Abbreviations: CSTE, Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; EPS, Enhanced Pertussis Surveillance; IQR, interquartile range.

aCalculated out of those with a known response. For pregnant patients: race (n = 69) and ethnicity (n = 73); for nonpregnant patients: race (n = 1316) and ethnicity (n = 1347); for total: race (n = 1385) and ethnicity (n = 1420).

bCalculated out of total number of patients that ever received Tdap (n = 24 for pregnant patients; n = 465 for nonpregnant patients; n = 489 for total).

cMean number of physician visits between cough onset date and the time of diagnosis. Calculated out of those with a known response. For pregnant patients, n = 75; for nonpregnant patients, n = 1390; for total, n = 1465.

dCalculated out of those with a known response. For pregnant patients, n=74; for nonpregnant patients, n=1420; for total, n=1494.

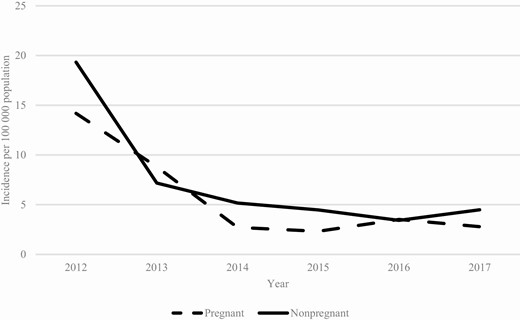

From 2012–2017, the incidence of pertussis among pregnant women ranged from 2.71/100 000 (2014) to 14.2/100 000 (2012). Among nonpregnant women, rates of pertussis were comparable, ranging from 3.4/10 000 (2016) to 19.3/100 000 (2012; Figure 1).

Pertussis incidences among women aged 18–44 years, by year and pregnancy status.

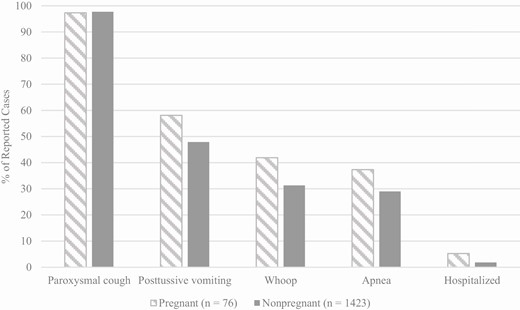

Among both pregnant and nonpregnant patients, paroxysmal cough was the most commonly reported clinical symptom (>97.0% of patients in both groups; Figure 2). Although a higher proportion of pregnant patients compared to nonpregnant patients reported posttussive vomiting (58.1% vs. 47.9%, respectively; P = .09), apnea (37.3% vs 29.0%, respectively; P = .11), and whoop (41.9% vs. 31.3%, respectively; P = .06), these differences were not statistically significant. The mean numbers of physician visits between cough onset and the time of diagnosis were 1.6 for pregnant pertussis patients (range, 0 to 6 visits) and 1.4 for nonpregnant pertussis patients (range, 0 to 10 visits; Table 1). The majority of pregnant (93.2%) and nonpregnant (95.0%) patients were prescribed antibiotics that were recommended for the treatment of pertussis, most commonly azithromycin or clarithromycin (>88% for both groups; Table 1) [14].

Reported pertussis symptoms and complications of pregnant and nonpregnant pertussis patients, 2012–2017. Pertussis symptoms were calculated out of those with a known response. Among pregnant women and nonpregnant women, paroxysms were reported by 75 and 1418 patients, respectively; posttussive vomit was reported by 74 and 1407, respectively; whoop was reported by 74 and 1390, respectively; apnea was reported by 75 and 1366, respectively; and hospitalization was reported by 76 and 1415, respectively. The P values for all comparisons were >.05.

A total of 31.6% (24/76) of pregnant patients and 32.7% (465/1423) of nonpregnant patients had received at least 1 dose of Tdap at any point in time before cough onset, including during the current pregnancy (P = .84; Table 1). Compared to nonpregnant patients, a higher proportion of pregnant patients received Tdap in the 2 years prior to disease onset (41.7 vs. 24.1%, respectively; P = .05); among the 10 pregnant patients who received Tdap in the 2 years prior to disease onset, only 3 received it during their current pregnancy. There were no differences in the clinical presentation of pregnant patients when stratified by timing of Tdap; among nonpregnant patients, a significantly higher proportion of whoop was reported among patients vaccinated 2 or more years prior to cough onset (34.2% vs. 20.9%, respectively; P = .01)

Overall, less than 6% of both pregnant and nonpregnant patients were hospitalized during their pertussis infection; 5.3% (4/76) of pregnant patients and 1.8% (26/1415) of nonpregnant patients (P = .06; Figure 2). The median length of hospitalization for both groups was 3 days (range for pregnant patients was 1 to 4 days; range for nonpregnant patients was 0 to 10 days). The 4 hospitalized pregnant patients ranged in age from 25 to 43 years and were in their second (n = 1) or third (n = 3) trimesters of pregnancy. Of the hospitalized patients, 1 had asthma and was a current smoker and 1 had underlying diabetes. Presenting symptoms in these women included shortness of breath (n = 4), paroxysmal cough (n = 4), productive cough (n = 2), posttussive vomiting (n = 1), chest pain (n = 1), and nasal congestion (n = 1). Of the 4 patients, 3 were treated with recommended antibiotics; for the untreated patient, approximately 21 days had passed between symptom onset and hospital admission.

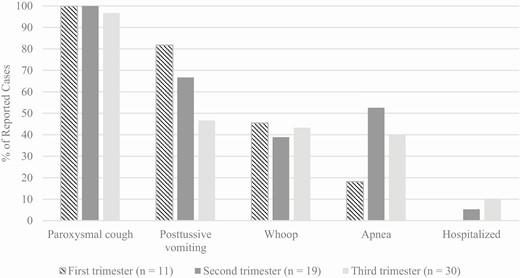

Among the 78.9% (60/76) of pregnant patients with a known trimester of pregnancy at time of cough onset, 11 (18.3%) were in their first trimester, 19 (31.7%) in their second trimester, and 30 (50.0%) in their third trimester. While over 95% of pregnant patients reported whoop and paroxysmal cough, regardless of trimester, the proportion of patients who reported posttussive vomiting was lower, and the proportion who were hospitalized was higher among patients further along in pregnancy (Figure 3). Apnea was most commonly reported during the second trimester of pregnancy.

Reported pertussis symptoms and complications of pregnant pertussis patients, by trimester of pregnancy, 2012–2017. Pertussis symptoms were calculated out of those with known responses for the first, second, and third trimesters: paroxysmal cough was reported by 10, 19, and 30 patients, respectively; posttussive vomit was reported by 11, 18, and 30, respectively; whoop was reported by 11, 18, and 30, respectively; apnea was reported by 11, 19, and 30, respectively; and hospitalization was reported by 11, 19, and 30, respectively.

Among infants born to pregnant patients with cough onset during the third trimester (n = 30) or with an unknown trimester of cough onset (n = 16), 3 had confirmed pertussis with onset between 7 and 21 days after birth; all 3 infants were hospitalized, and none died. For each infant patient, the mother’s cough onset date was within 21 days of the infant’s birth. However, the mother was identified as the source of infection for only 1 of the infant patients; for the remaining 2 infants, a sibling (ages 10 and 12 years) was identified as the source. No Tdap doses were recorded for any of the 3 mothers.

Discussion

Little is known about the burden and characteristics of pertussis in pregnant women, who may be at higher risk of severe disease and pertussis-related complications. In this large, multi-state analysis of pertussis among women of childbearing age in the United States, we found that the clinical presentation and severity of pertussis illness are comparable among pregnant and nonpregnant women. Unlike influenza infection, for which pregnant women are more likely to experience severe complications and hospitalization [6], our data suggest that pregnancy may not place a woman at increased risk for severe pertussis infection. The present findings support published reports from smaller case series studies, showing that while pregnant patients may present with prolonged, spasmodic cough and occasional posttussive vomiting, reported infections are generally unremarkable compared to the general adult population [10–12, 15, 16]. While we did find a slightly higher proportion of some pertussis clinical symptoms and hospitalizations reported among pregnant patients compared to nonpregnant patients, small sample sizes limited our ability to detect statistically significant differences. Unlike prior studies, our analysis of population-based surveillance data also allowed us to compare the burden of disease among pregnant and nonpregnant women. To our knowledge, this has not been previously reported. We found a similarly low burden of pertussis in pregnant women as what has been shown in surveillance studies of adult pertussis, and we found no differences in incidence of pertussis between pregnant and nonpregnant women [1, 17].

Upon examination of the relationship between clinical presentation and the timing of pregnancy, we found that whoop and paroxysmal cough, common symptoms of pertussis infections in adults, were consistently reported among pregnant patients regardless of pregnancy trimester. In contrast, posttussive vomiting, despite small numbers, was most commonly reported among pregnant patients with cough onset during the first trimester (82%), and was less frequent among those with disease onset later in pregnancy. Because nausea and vomiting are known to affect more than half of pregnant women and are most likely to occur during the first trimester of pregnancy [18], this finding is not surprising, as paroxysmal coughing in the presence of nausea may be more likely to induce posttussive vomiting. We also found that the proportion of pregnant patients hospitalized for their pertussis illness was highest among women diagnosed later in pregnancy. This may, in part, be explained by clinicians having a lower threshold to hospitalize women who develop infections late in pregnancy. Additionally, pertussis symptoms may be exacerbated by physical changes that accompany late pregnancy, also increasing the likelihood of hospitalization. Of the 4 pregnant patients that were hospitalized in our analysis, 3 were in their third trimester of pregnancy at the time of cough onset.

Despite the effectiveness of Tdap vaccination during pregnancy at preventing infant pertussis, uptake of the strategy has progressed slowly since introduction in the United States, from 27.0% in 2014, the first year for which national coverage data are available, to only 54.9% in 2018 [19–27]. In our study, we observed a higher proportion of pregnant patients than nonpregnant patients having evidence of Tdap receipt within 2 years of their pertussis diagnosis. While this finding may reflect the current recommendation for Tdap vaccination during every pregnancy, only 3 of the 10 pregnant women with pertussis in this study had evidence of Tdap receipt during the current pregnancy, and we were unable to determine whether other Tdap vaccinations occurred during prior pregnancies. Although the primary rationale for Tdap vaccination during pregnancy is to provide maternal antibodies to protect the newborn, Tdap vaccination also provides direct protection to the vaccinated woman, helping to minimize not only the burden and severity of disease, but also secondary transmission of disease to the newborn infant. In our study, 3 patients gave birth to infants who were diagnosed with pertussis during the early weeks of life; none of these mothers reported ever having received Tdap. Although the mother was identified as the source of infection for only 1 of the infant patients, this finding underscores the importance of Tdap vaccination during pregnancy, as this highly effective strategy provides protection to the infant regardless of the infection source. However, in settings where Tdap vaccination is not administered during pregnancy, recognition and prompt treatment of pertussis infections among women during late pregnancy are important to help prevent subsequent infections among vulnerable infants.

An analysis of enhanced, population-based surveillance data allowed not only the characterization of the clinical presentation of pertussis illness among pregnant women, but also the calculation of disease incidence. Nevertheless, there were some limitations to our analysis. Although we were unable to detect differences in the clinical presentation of disease between pregnant and nonpregnant patients, we had no ability to measure the intensity or duration of reported symptoms, and this may have masked potential differences in severity. Additionally, for pregnant women with pertussis, there may be symptoms or complications related to the physiologic changes of pregnancy that were not routinely captured through surveillance, and we did not follow up on longer-term outcomes among the infants born to these women. There was also the potential for misclassification of pregnancy status, especially for women earlier in pregnancy at the time of their pertussis infection. If women in early pregnancy had more severe symptoms or outcomes and were misclassified as being nonpregnant, these differences would not have been detected. We were also limited in our ability to fully examine the potential role of underlying conditions in this population, as the collection of these data was limited to hospitalized patients. In our analysis, only 4 pregnant patients were hospitalized, 2 of which reported underlying conditions. It is unknown whether underlying conditions were as prevalent among the nonhospitalized patients and whether differences existed overall between pregnant and nonpregnant women. Lastly, live birth data were utilized to estimate the number of pregnant women in the surveillance catchment area. Although live birth data underestimate the number of pregnancies that occur each year, leading to an overestimate in the disease burden, we found no difference in incidence of pertussis between pregnant and nonpregnant women.

As pertussis continues to circulate widely in the United States, identifying and monitoring disease trends in those populations that may be at increased risk for pertussis morbidity and severe outcomes remains central to the successful prevention and control of the disease. Our analysis of US surveillance data provides a valuable first look at the burden and characteristics of pertussis in pregnant women. While we found minimal differences between pregnant and nonpregnant female cases of childbearing age, further characterization of disease in a larger sample of pregnant women is warranted. The prompt diagnosis and treatment of pertussis infections in pregnant women is important to help minimize the impact of disease and prevent further transmission to newborn infants or other household contacts who are in contact with young infants. Just as importantly, maximizing current pertussis prevention strategies, specifically maternal Tdap immunization during pregnancy, ensures protection not only to the newborn infant but also to the pregnant mother.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the Enhanced Pertussis Surveillance (EPS) surveillance staff for collecting the data on pertussis cases used for this analysis, including Karen Edge (CO), Kristen Soto (CT), Roxanne Ryan (CT), Dana Goodenough (GA), Stepy Thomas (GA), Victor Cruz (MN), Yeng Vang (MN), Kari Burzlaff (NY), Rachel Wester (NY), Glenda Smith (NY), Nancy Spina (NY), Joanie Coleman (OR), Lisa Ferguson (OR), and Paul Cieslak (OR). They also thank Christine Miner and Matt Cole for EPS data management, and Amy Blain and Nong Shang for their valuable input.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial support. This work was conducted as part of the Enhanced Pertussis Surveillance through the Emerging Infections Program Network (EIP). The EIP is supported through a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cooperative agreement.

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

Author notes

Present affiliation: Oregon Health Authority, Portland, Oregon, USA

Present affiliation: Espanola Hospital and Santa Fe Medical Center, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA