-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jean B Nachega, Ashraf Grimwood, Hassan Mahomed, Geoffrey Fatti, Wolfgang Preiser, Oscar Kallay, Placide K Mbala, Jean-Jacques T Muyembe, Edson Rwagasore, Sabin Nsanzimana, Daniel Ngamije, Jeanine Condo, Mohsin Sidat, Emilia V Noormahomed, Michael Reid, Beatrice Lukeni, Fatima Suleman, Alfred Mteta, Alimuddin Zumla, From Easing Lockdowns to Scaling Up Community-based Coronavirus Disease 2019 Screening, Testing, and Contact Tracing in Africa—Shared Approaches, Innovations, and Challenges to Minimize Morbidity and Mortality, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 72, Issue 2, 15 January 2021, Pages 327–331, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa695

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The arrival of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on the African continent resulted in a range of lockdown measures that curtailed the spread of the infection but caused economic hardship. African countries now face difficult choices regarding easing of lockdowns and sustaining effective public health control measures and surveillance. Pandemic control will require efficient community screening, testing, and contact tracing; behavioral change interventions; adequate resources; and well-supported, community-based teams of trained, protected personnel. We discuss COVID-19 control approaches in selected African countries and the need for shared, affordable, innovative methods to overcome challenges and minimize mortality. This crisis presents a unique opportunity to align COVID-19 services with those already in place for human immunodeficiency virus, tuberculosis, malaria, and non communicable diseases through mobilization of Africa’s interprofessional healthcare workforce. By addressing the challenges, the detrimental effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on African citizens can be minimized.

As of 26 May 2020, the World Health Organization Africa Region (WHO-AFRO) had reported 80 979 coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases with 2193 deaths from 45 countries, with South Africa having the highest confirmed number of cases (23 615) [1]. While these numbers are smaller than those from the United States and Europe, the WHO estimates that up to 190 000 people could die in Africa from COVID-19 if it is not brought under control [2]. African countries face the difficult task of striking a delicate balance between the institution of effective measures to curtail the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and minimization of economic hardship for large sections of the population by easing lockdown measures [3]. We discuss COVID-19 screening, testing, and contact tracing experiences from selected African countries and the need for shared, affordable approaches and innovations to overcome challenges and minimize mortality rates.

AFRICA’S DILEMMA

Scalable labor- and cost-efficient door-to-door contact tracing calls for increased staffing and national funding. Extensive human resource mobilization will be necessary to respond effectively [4]. Worryingly, only 15 African countries currently have health infrastructures that include a functioning national public health institute. COVID-19 surveillance post lockdown will require operations centers for proactive digitalized surveillance linked with the capacity for rapid diagnostics and highly trained response teams. Nonetheless, these investment costs will need to be weighed against the economic costs of inadequate action; analysis shows that COVID-19 will cost the region between $37 billion and $79 billion in output losses in 2020 [5]. Waiting for assistance from donor countries is frowned upon by the Africa Centers for Disease Control (CDC) [4] since aid was slow to arrive at the beginning of the pandemic. African countries can develop and sustain effective, local COVID-19 control programs.

COMMUNITY COVID-19 SCREENING EXPERIENCES

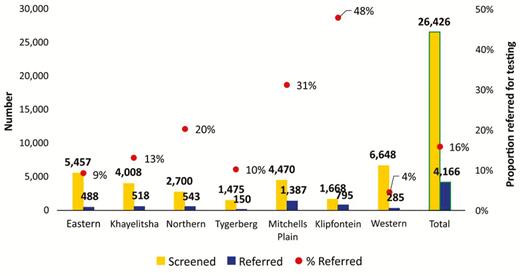

In South Africa, approximately 28 000 community healthcare workers (CHCWs) have been deployed. By the end of April 2020, more than 6 million people had been screened and 42 000 referred for testing. Figure 1 shows COVID-19 screening activity by subdistrict in Cape Town, the epicenter of the pandemic in South Africa. Sixteen percent of those screened were referred for testing at health facilities (range, 4%– 48% by subdistrict). Table 1 describes the implementation challenges and possible solutions.

Challenges and Possible Solutions for Scaling Up Coronavirus Disease 2019 Community-based Screening, Testing, and Contact Tracing Experiences from Select African Countries

| Target Country by Burden . | Early and Late Challenges . | Priority Solutions . |

|---|---|---|

| South Africa | • Fake news adding to anxiety, rejection, and noncooperation • Staff anxiety about the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection • Rejection and racism experienced by some CHCWs due to clashing cultures, language barriers • Stigmatization of workers by communities because they are wearing PPE • Some communities reject screening • Long turnaround time of PCR results • Small spaces within the houses visited, overcrowding in some houses • Elderly and disabled cannot reach screening/testing sites • Hard-to-reach populations: homeless, sex workers, children, essential workers, prisoners • Instability of mobile device apps for collecting household data • Difficulty in obtaining GPS data of home visits • Parallel data collection system requirements for the Department of Health and external funders | ➢ Enforce ongoing communication to communities in local languages using multiple platforms and players to immediately address inaccuracies circulating on social media by using authoritative voices, daily “myth busters” ➢ Have staff and communities actively and regularly use symptom self-screening tools ➢ Actively monitor symptoms with feedback from management on a daily basis ➢ Monitor temperature of staff and people screened for greater reassurance ➢ Ease access to testing for staff by having testing centers at workplaces ➢ Implement PoC COVID-19 testing at pharmacies ➢ Support staff during their quarantine while waiting for results, especially with management of their households/families/children ➢ Improve the turnaround time for staff SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing outcomes ➢ Establish a referral service whereby communities and their household members can access telephonic assistance, counseling, and face-to-face emotional support, if required |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | • Some community members do not believe that COVID-19 exists• Poverty levels limit respect for the application of barrier measures• Screening is centralized at the national level that causes a delay in delivery of results to provinces • Contact tracing is done only by a small team in provinces due to shortage of PPEs • Shortage of GeneXpert machines • Shortage of reagents/cartridges with increased demand for suspected COVID-19 cases | ➢ Scale up community COVID-19 sensitization and barrier measures in public places ➢ Leverage infrastructure, human resources, and training platform of Ebola viral disease for COVID-19 ➢ Decentralize screening and PCR testing using PoC machines in provinces ➢ Increase contributions of government funding and international partners for COVID-19 response in providing PPE for healthcare workers, medical equipment including ventilators and medicines |

| Tanzania | • Shortage of PPE • Laboratory testing insufficiencies • Shortage of adequately trained CHCWs | ➢ Build local capacity to produce PPE ➢ Refurbish the national reference laboratory ➢ Scale up trained multiprofessional CHCWs for COVID-19 screening, testing, and contact tracing |

| Rwanda | • Limited laboratory capacity to run 1500 or more tests per day• Long turnaround time of PCR results, especially for people quarantined in peripheral sites • Difficult to track movement of truck drivers using modern devices and GPS | ➢ Pool testing approach for COVID-19 mass testing ➢ Test GeneXpert platform for COVID-19 for phases 2 and 3 of lockdown ➢ Establish COVID-19 testing capacity using existing platforms at decentralized level ➢ Use tracking devices embedded with GPS for trucks drivers |

| Mozambique | • Limited financial resources to purchase diagnostic kits and other related supplies • Limited laboratory infrastructure to process samples • Limited number of laboratory technicians to process samples • Scarcity of PPE for health workforce within the National Health Service • Fear and anxiety among health workforce for the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection • Myths and misconceptions about the cause of COVID-19 • Poverty and lack of formal employment, which makes it difficult to keep affected people in confinement • Hard-to-reach populations: people living in areas of armed conflicts | ➢ Fund mobilization through external government entities, academia, philanthropic institutions, and civilian community ➢ Optimize and share existing GeneXpert platform for tuberculosis testing and other PCR equipment from other research laboratories ➢ Refresh and train existing laboratory technicians working in molecular diagnosis throughout the country ➢ Provide PPE and refresh trainings on biosafety measures, and ensure social support in case health workforce gets infected ➢ Strongly advocate and use all means of communication to increase awareness of disease within the population ➢ Have the government and partners distribute basic food baskets and other necessities ➢ Strengthen epidemiological surveillance, identification of cases and contact tracing, and monitoring of individuals in quarantine and isolation ➢ Strengthen hospital conditions for COVID-19 patients with moderate to severe diseases and hospital infection prevention interventions |

| Target Country by Burden . | Early and Late Challenges . | Priority Solutions . |

|---|---|---|

| South Africa | • Fake news adding to anxiety, rejection, and noncooperation • Staff anxiety about the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection • Rejection and racism experienced by some CHCWs due to clashing cultures, language barriers • Stigmatization of workers by communities because they are wearing PPE • Some communities reject screening • Long turnaround time of PCR results • Small spaces within the houses visited, overcrowding in some houses • Elderly and disabled cannot reach screening/testing sites • Hard-to-reach populations: homeless, sex workers, children, essential workers, prisoners • Instability of mobile device apps for collecting household data • Difficulty in obtaining GPS data of home visits • Parallel data collection system requirements for the Department of Health and external funders | ➢ Enforce ongoing communication to communities in local languages using multiple platforms and players to immediately address inaccuracies circulating on social media by using authoritative voices, daily “myth busters” ➢ Have staff and communities actively and regularly use symptom self-screening tools ➢ Actively monitor symptoms with feedback from management on a daily basis ➢ Monitor temperature of staff and people screened for greater reassurance ➢ Ease access to testing for staff by having testing centers at workplaces ➢ Implement PoC COVID-19 testing at pharmacies ➢ Support staff during their quarantine while waiting for results, especially with management of their households/families/children ➢ Improve the turnaround time for staff SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing outcomes ➢ Establish a referral service whereby communities and their household members can access telephonic assistance, counseling, and face-to-face emotional support, if required |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | • Some community members do not believe that COVID-19 exists• Poverty levels limit respect for the application of barrier measures• Screening is centralized at the national level that causes a delay in delivery of results to provinces • Contact tracing is done only by a small team in provinces due to shortage of PPEs • Shortage of GeneXpert machines • Shortage of reagents/cartridges with increased demand for suspected COVID-19 cases | ➢ Scale up community COVID-19 sensitization and barrier measures in public places ➢ Leverage infrastructure, human resources, and training platform of Ebola viral disease for COVID-19 ➢ Decentralize screening and PCR testing using PoC machines in provinces ➢ Increase contributions of government funding and international partners for COVID-19 response in providing PPE for healthcare workers, medical equipment including ventilators and medicines |

| Tanzania | • Shortage of PPE • Laboratory testing insufficiencies • Shortage of adequately trained CHCWs | ➢ Build local capacity to produce PPE ➢ Refurbish the national reference laboratory ➢ Scale up trained multiprofessional CHCWs for COVID-19 screening, testing, and contact tracing |

| Rwanda | • Limited laboratory capacity to run 1500 or more tests per day• Long turnaround time of PCR results, especially for people quarantined in peripheral sites • Difficult to track movement of truck drivers using modern devices and GPS | ➢ Pool testing approach for COVID-19 mass testing ➢ Test GeneXpert platform for COVID-19 for phases 2 and 3 of lockdown ➢ Establish COVID-19 testing capacity using existing platforms at decentralized level ➢ Use tracking devices embedded with GPS for trucks drivers |

| Mozambique | • Limited financial resources to purchase diagnostic kits and other related supplies • Limited laboratory infrastructure to process samples • Limited number of laboratory technicians to process samples • Scarcity of PPE for health workforce within the National Health Service • Fear and anxiety among health workforce for the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection • Myths and misconceptions about the cause of COVID-19 • Poverty and lack of formal employment, which makes it difficult to keep affected people in confinement • Hard-to-reach populations: people living in areas of armed conflicts | ➢ Fund mobilization through external government entities, academia, philanthropic institutions, and civilian community ➢ Optimize and share existing GeneXpert platform for tuberculosis testing and other PCR equipment from other research laboratories ➢ Refresh and train existing laboratory technicians working in molecular diagnosis throughout the country ➢ Provide PPE and refresh trainings on biosafety measures, and ensure social support in case health workforce gets infected ➢ Strongly advocate and use all means of communication to increase awareness of disease within the population ➢ Have the government and partners distribute basic food baskets and other necessities ➢ Strengthen epidemiological surveillance, identification of cases and contact tracing, and monitoring of individuals in quarantine and isolation ➢ Strengthen hospital conditions for COVID-19 patients with moderate to severe diseases and hospital infection prevention interventions |

Abbreviations: CHCW, community healthcare worker; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; GPS, global positioning system; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PoC, point of care; PPE, personal protection equipment; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Challenges and Possible Solutions for Scaling Up Coronavirus Disease 2019 Community-based Screening, Testing, and Contact Tracing Experiences from Select African Countries

| Target Country by Burden . | Early and Late Challenges . | Priority Solutions . |

|---|---|---|

| South Africa | • Fake news adding to anxiety, rejection, and noncooperation • Staff anxiety about the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection • Rejection and racism experienced by some CHCWs due to clashing cultures, language barriers • Stigmatization of workers by communities because they are wearing PPE • Some communities reject screening • Long turnaround time of PCR results • Small spaces within the houses visited, overcrowding in some houses • Elderly and disabled cannot reach screening/testing sites • Hard-to-reach populations: homeless, sex workers, children, essential workers, prisoners • Instability of mobile device apps for collecting household data • Difficulty in obtaining GPS data of home visits • Parallel data collection system requirements for the Department of Health and external funders | ➢ Enforce ongoing communication to communities in local languages using multiple platforms and players to immediately address inaccuracies circulating on social media by using authoritative voices, daily “myth busters” ➢ Have staff and communities actively and regularly use symptom self-screening tools ➢ Actively monitor symptoms with feedback from management on a daily basis ➢ Monitor temperature of staff and people screened for greater reassurance ➢ Ease access to testing for staff by having testing centers at workplaces ➢ Implement PoC COVID-19 testing at pharmacies ➢ Support staff during their quarantine while waiting for results, especially with management of their households/families/children ➢ Improve the turnaround time for staff SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing outcomes ➢ Establish a referral service whereby communities and their household members can access telephonic assistance, counseling, and face-to-face emotional support, if required |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | • Some community members do not believe that COVID-19 exists• Poverty levels limit respect for the application of barrier measures• Screening is centralized at the national level that causes a delay in delivery of results to provinces • Contact tracing is done only by a small team in provinces due to shortage of PPEs • Shortage of GeneXpert machines • Shortage of reagents/cartridges with increased demand for suspected COVID-19 cases | ➢ Scale up community COVID-19 sensitization and barrier measures in public places ➢ Leverage infrastructure, human resources, and training platform of Ebola viral disease for COVID-19 ➢ Decentralize screening and PCR testing using PoC machines in provinces ➢ Increase contributions of government funding and international partners for COVID-19 response in providing PPE for healthcare workers, medical equipment including ventilators and medicines |

| Tanzania | • Shortage of PPE • Laboratory testing insufficiencies • Shortage of adequately trained CHCWs | ➢ Build local capacity to produce PPE ➢ Refurbish the national reference laboratory ➢ Scale up trained multiprofessional CHCWs for COVID-19 screening, testing, and contact tracing |

| Rwanda | • Limited laboratory capacity to run 1500 or more tests per day• Long turnaround time of PCR results, especially for people quarantined in peripheral sites • Difficult to track movement of truck drivers using modern devices and GPS | ➢ Pool testing approach for COVID-19 mass testing ➢ Test GeneXpert platform for COVID-19 for phases 2 and 3 of lockdown ➢ Establish COVID-19 testing capacity using existing platforms at decentralized level ➢ Use tracking devices embedded with GPS for trucks drivers |

| Mozambique | • Limited financial resources to purchase diagnostic kits and other related supplies • Limited laboratory infrastructure to process samples • Limited number of laboratory technicians to process samples • Scarcity of PPE for health workforce within the National Health Service • Fear and anxiety among health workforce for the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection • Myths and misconceptions about the cause of COVID-19 • Poverty and lack of formal employment, which makes it difficult to keep affected people in confinement • Hard-to-reach populations: people living in areas of armed conflicts | ➢ Fund mobilization through external government entities, academia, philanthropic institutions, and civilian community ➢ Optimize and share existing GeneXpert platform for tuberculosis testing and other PCR equipment from other research laboratories ➢ Refresh and train existing laboratory technicians working in molecular diagnosis throughout the country ➢ Provide PPE and refresh trainings on biosafety measures, and ensure social support in case health workforce gets infected ➢ Strongly advocate and use all means of communication to increase awareness of disease within the population ➢ Have the government and partners distribute basic food baskets and other necessities ➢ Strengthen epidemiological surveillance, identification of cases and contact tracing, and monitoring of individuals in quarantine and isolation ➢ Strengthen hospital conditions for COVID-19 patients with moderate to severe diseases and hospital infection prevention interventions |

| Target Country by Burden . | Early and Late Challenges . | Priority Solutions . |

|---|---|---|

| South Africa | • Fake news adding to anxiety, rejection, and noncooperation • Staff anxiety about the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection • Rejection and racism experienced by some CHCWs due to clashing cultures, language barriers • Stigmatization of workers by communities because they are wearing PPE • Some communities reject screening • Long turnaround time of PCR results • Small spaces within the houses visited, overcrowding in some houses • Elderly and disabled cannot reach screening/testing sites • Hard-to-reach populations: homeless, sex workers, children, essential workers, prisoners • Instability of mobile device apps for collecting household data • Difficulty in obtaining GPS data of home visits • Parallel data collection system requirements for the Department of Health and external funders | ➢ Enforce ongoing communication to communities in local languages using multiple platforms and players to immediately address inaccuracies circulating on social media by using authoritative voices, daily “myth busters” ➢ Have staff and communities actively and regularly use symptom self-screening tools ➢ Actively monitor symptoms with feedback from management on a daily basis ➢ Monitor temperature of staff and people screened for greater reassurance ➢ Ease access to testing for staff by having testing centers at workplaces ➢ Implement PoC COVID-19 testing at pharmacies ➢ Support staff during their quarantine while waiting for results, especially with management of their households/families/children ➢ Improve the turnaround time for staff SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing outcomes ➢ Establish a referral service whereby communities and their household members can access telephonic assistance, counseling, and face-to-face emotional support, if required |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | • Some community members do not believe that COVID-19 exists• Poverty levels limit respect for the application of barrier measures• Screening is centralized at the national level that causes a delay in delivery of results to provinces • Contact tracing is done only by a small team in provinces due to shortage of PPEs • Shortage of GeneXpert machines • Shortage of reagents/cartridges with increased demand for suspected COVID-19 cases | ➢ Scale up community COVID-19 sensitization and barrier measures in public places ➢ Leverage infrastructure, human resources, and training platform of Ebola viral disease for COVID-19 ➢ Decentralize screening and PCR testing using PoC machines in provinces ➢ Increase contributions of government funding and international partners for COVID-19 response in providing PPE for healthcare workers, medical equipment including ventilators and medicines |

| Tanzania | • Shortage of PPE • Laboratory testing insufficiencies • Shortage of adequately trained CHCWs | ➢ Build local capacity to produce PPE ➢ Refurbish the national reference laboratory ➢ Scale up trained multiprofessional CHCWs for COVID-19 screening, testing, and contact tracing |

| Rwanda | • Limited laboratory capacity to run 1500 or more tests per day• Long turnaround time of PCR results, especially for people quarantined in peripheral sites • Difficult to track movement of truck drivers using modern devices and GPS | ➢ Pool testing approach for COVID-19 mass testing ➢ Test GeneXpert platform for COVID-19 for phases 2 and 3 of lockdown ➢ Establish COVID-19 testing capacity using existing platforms at decentralized level ➢ Use tracking devices embedded with GPS for trucks drivers |

| Mozambique | • Limited financial resources to purchase diagnostic kits and other related supplies • Limited laboratory infrastructure to process samples • Limited number of laboratory technicians to process samples • Scarcity of PPE for health workforce within the National Health Service • Fear and anxiety among health workforce for the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection • Myths and misconceptions about the cause of COVID-19 • Poverty and lack of formal employment, which makes it difficult to keep affected people in confinement • Hard-to-reach populations: people living in areas of armed conflicts | ➢ Fund mobilization through external government entities, academia, philanthropic institutions, and civilian community ➢ Optimize and share existing GeneXpert platform for tuberculosis testing and other PCR equipment from other research laboratories ➢ Refresh and train existing laboratory technicians working in molecular diagnosis throughout the country ➢ Provide PPE and refresh trainings on biosafety measures, and ensure social support in case health workforce gets infected ➢ Strongly advocate and use all means of communication to increase awareness of disease within the population ➢ Have the government and partners distribute basic food baskets and other necessities ➢ Strengthen epidemiological surveillance, identification of cases and contact tracing, and monitoring of individuals in quarantine and isolation ➢ Strengthen hospital conditions for COVID-19 patients with moderate to severe diseases and hospital infection prevention interventions |

Abbreviations: CHCW, community healthcare worker; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; GPS, global positioning system; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PoC, point of care; PPE, personal protection equipment; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Coronavirus disease 2019 community screening by subdistrict in Cape Town, South Africa, 4 April 2020 to 22 May 2020.

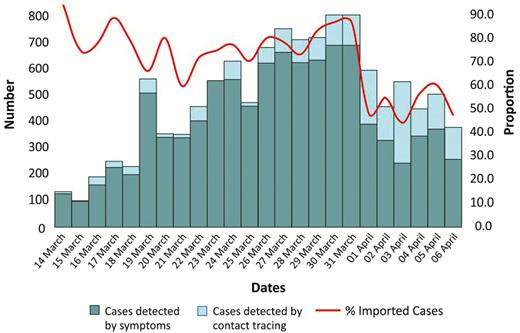

While the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is confronting the COVID-19 crisis, its eastern northern province Kivu faces the last phase of its tenth Ebola virus disease (EBV) outbreak response in the last 40 years. The first confirmed COVID-19 case in DRC was reported on 10 March 2020 in the capital city Kinshasa, and cases totaled 2304 and 66 deaths as of 26 May 2020 [4]. Figure 2 shows that as the proportion of imported cases decreases, there is a steady increase in community transmission and confirmed positive contacts in Kinshasa, the epicenter of the epidemic in DRC. EBV infrastructure and human experience in case finding are now being applied for the COVID-19 response. Also, the DRC government’s COVID-19 task response structure was incorporated into existing health structures that are tackling human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), tuberculosis (TB), malaria, and noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). ICAP at Columbia University’s Resilient and Responsive Health Systems (RRHS) project in DRC, supported by the US Health Resources and Services Administration, is implementing a multiprofessional health team of nurses, midwives, doctors, pharmacists, medical students, and CHCWs in COVID-19 sensitization, screening, and testing referral activities endorsed by the ministry of health, the community, and faith leaders.

Coronavirus disease 2019 daily case numbers in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 15 March 2020 to 2 April 2020.

The United Republic of Tanzania, with 480 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 21 deaths as of 26 May 2020 [1], introduced “Health Commandos,” CHCWs specific for the COVID-19 response, for every street in the country beginning with the worst hit city of Dar-es-Salaam. Trained and wearing special gear, they walked the streets educating the community on social distancing, hygiene measures, screening, and referrals for COVID-19 testing. In Rwanda, proactive screening, testing, isolation of confirmed first COVID-19 cases, and contact tracing led to travel bans and country lockdown, which helped flatten the curve and contain the epidemic. There were only 336 confirmed cases and no deaths as of 26 May 2020. Of note, screening is done mainly by doctors and other CHCWs. An innovative role for final-year medical students trained in sample collection, transportation, and analysis under the National Reference Laboratory allowed testing of 30 000 people as of 30 April 2020; 243 were COVID-19 positive. Fortunately, most of the cases were young and asymptomatic, and 104 recovered.

In Mozambique, by the end of May, there were more than 700 000 individuals screened, 15 090 quarantined, and more than 8796 tested, from which 209 were positive for COVID-19. Unfortunately, displaced and migrant populations (eg, north and central Mozambique) have not been reached for screening or implementation of mitigating measures due to political instability and terrorism.

SARS-COV-2 TESTING: LOGISTICS AND CHALLENGES

Globally, the current gold standard test for SARS-CoV-2 infection is detection of viral RNA in a sample from the respiratory tract by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction [6–8]. Specialized laboratory facilities with skilled staff and expensive equipment to undertake these tests are scarce in most African countries. Centralized laboratories with testing facilities require samples to be transported, and thus turnaround times may be suboptimal, resulting in loss to follow-up. Point-of-care (PoC) or near-patient solutions are preferable [9, 10]. The GeneXpert platform, already in place for TB testing across Africa, allows the use of SARS-CoV-2 cartridges, but drawbacks include cost and supply constraints. PoC viral antigen detection is not yet sufficiently sensitive [11]. The use of patient self-collected nasal swabs or saliva samples would be easier and safer than nasopharyngeal swabbing by healthcare staff. Serological testing for antiviral antibodies is now available [12] but only indicates recent or past infection and is unsuitable for diagnosing active COVID-19 cases. Importantly, seropositivity does not indicate immunity to SARS-CoV-2 [13]. However, antibody testing can allow reconstruction of transmission chains during outbreaks and community prevalence surveillance.

While the Africa CDC is facilitating regional collaborations and procurement and distribution of diagnostic tests across Africa, important operational and resource issues need to be addressed to avoid stockouts, supply chain challenges, and competition among countries [4]. Incorporation of private and nongovernmental sector laboratories in the rollout of testing and the use of existing available PoC diagnostic platforms for other diseases (eg, TB, HIV) are promising strategies to improve availability and turnaround times and reduce reliance on central laboratories (Table 1). Ideally, diagnostic tests and reagents should be produced within Africa. Also, PoC COVID-19 testing at pharmacies may improve access to care and effective use of the available healthcare workforce.

CONTACT TRACING

Case finding and contact tracing depend on substantial COVID-19 testing capability, sample throughput, and rapid turnaround times [14, 15]. In the Western Cape Province of South Africa, public and private laboratory results of confirmed COVID-19 cases are communicated electronically and assigned to provincially based telephonic teams who then contact cases and their contacts. Where this is not feasible, the involved persons are relocated to designated isolation facilities. Cases and contacts are then monitored for 14 days. Workplace and airline contacts are also pursued. Legislation is available for mandatory isolation, should any person be unwilling to undergo the necessary self-isolation.

In Rwanda, once a COVID-19 case is suspected, a sample is collected at a satellite site and sent to the National Reference Laboratory for testing, and the result is available within 10 hours. If positive, the index case is isolated. Contact tracing entails the following steps: (1) a case investigation procedure to identify all clinical symptoms; (2) memory history to recall all possible contacts during the window period, 2 to 14 days before the onset of the symptoms, who were within 1 meter of the index case; and (3) a roster of close contacts of the index case within the window period (for subsequent screening). As of 30 April 2020, 3657 individuals linked to COVID-19 cases had been traced by command posts across the country.

In DRC and Tanzania, contact tracing is conducted by CHCWs who use mobile phone calls and short messaging system and home visits, if necessary. In selected provinces of DRC, a multiprofessional health team (described earlier) is being implemented for contact tracing by a RRHS project. In Mozambique, contact tracing is done by the staff of the National Institute of Health, medical residents, and students from the master program on Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training, supported by the CDC [16]. These cadres are trained and skilled in applying a screening epidemiological case identification tool and on procedures for contact tracing and surveillance of quarantined individuals and home-isolated COVID-19 cases. This strategy has proven effective thus far because of the limited number of cases and contacts to trace at a specific moment in time.

CONCLUSIONS AND WAY FORWARD

Resource-constrained African governments face difficult choices regarding surveillance and easing of lockdowns. Control of the COVID-19 pandemic will be possible only with efficient community screening, testing, and contact tracing and with behavioral change interventions, which require adequate resources and a well-supported, community-based team of trained, protected personnel. Every part of this public health chain needs to be strengthened. With an already understaffed health force, Africa cannot afford the 10% infection rate of healthcare workers seen in selected European countries. This crisis presents a unique opportunity to align COVID-19 services with those already in place for HIV, TB, malaria, and NCDs through mobilization of Africa’s interprofessional healthcare workforce to contain the pandemic. By addressing the challenges, the detrimental effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on African citizens can be minimized.

Notes

Financial support. J. B. N. is supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant 5U01AI069521; Stellenbosch University Clinical Trial Unit of the AIDS Clinical Trial Group) as well as NIH/Fogarty International Center (FIC; grant 1R25TW011217-01; African Association for Health Professions Education and Research and grant 1D43TW010937-01A1; University of Pittsburgh HIV Comorbidities Research Training Program in South Africa) and is co-principal investigator of TOGETHER, an adaptive, randomized clinical trial of novel agents for the treatment of high-risk coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) patients in South Africa supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. E. V. N. is supported by NIH/FIC (grant 1R25TW011216-01; Health Professionals Education Partnership Initiative and grant TW 010135-05; Enhanced Advanced Biomedical Research Training for Mozambique), Eduardo Mondlane University, Mozambique Institute for Health Education and Research and University of California San Diego. F.S. is supported by NIH/ FIC (grant 1R25TW011217-01; African Association for Health Professions Education and Research). B. L. is supported by ICAP at Columbia University, through PEPFAR funding from the US Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). A. Z. is a co-principal investigator of the Pan-African Network on Emerging and Re-Emerging Infections (PANDORA-ID-NET; https://www.pandora-id.net/) funded by the EU Horizon 2020 Framework Program for Research and Innovation, has received an NIH Research Senior Investigator award, and reports grants from European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership outside the submitted work. A. M. reports grants from NIH/FIC outside the submitted work. M. R. reports grants from HRSA outside the submitted work.

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References