-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Maura Manion, Niamh Lynn, Luxin Pei, Dima A Hammoud, Elizabeth Laidlaw, Gregg Roby, Dorinda Metzger, Yolanda Mejia, Andrea Lisco, Adrian Zelazny, Steve Holland, Marie-Louise Vachon, Matthew Scherer, Colm Bergin, Irini Sereti, To Induce Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome or Suppress It: The Spectrum of Mycobacterium genavense in the Antiretroviral Era, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 72, Issue 2, 15 January 2021, Pages 315–318, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa753

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Mycobacterium genavense is a challenging opportunistic pathogen to diagnose and manage in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Persistent immunosuppression or protracted immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome can lead to complicated clinical courses. We describe 3 cases of M. genavense in patients with HIV representing the spectrum between disease burden and strength of immune response.

Mycobacterium genavense is an opportunistic pathogen in people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) discovered in the 1990s, named for a person with HIV from Geneva who presented with a disseminated nontuberculous mycobacterium that did not grow on solid media [1, 2]. Mycobacterium genavense is slow growing, does not grow on conventional solid media, and typically requires molecular techniques for diagnosis [3–5]. It has a similar clinical presentation as Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) with fever, weight loss, and abdominal involvement [6].

In the preantiretroviral therapy (ART) era, patients with M. genavense had poor prognosis with a median survival of less than a year [3, 7–9]. Currently, in the ART era, survival is improved, but there is still significant morbidity and mortality with protracted clinical courses that may include immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) [6, 10]. The optimal management of these patients is unknown and the fastidious nature of M. genavense makes it difficult to determine if persistent symptoms are due to overwhelming disease burden in the absence of adequate immune restoration vs severe or relapsing IRIS. We describe 3 cases of M. genavense with prolonged clinical courses, the steps taken to determine the driving etiology, and our management approach. Patient 1 and 2 were participants of a National Institutes of Health (NIH) institutional review board–approved protocol (PANDORA, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT0214705) and had given informed consent.

Patient 1

A 26-year-old man with HIV/AIDS (Figure 1A) presented 3 months after ART initiation with diarrhea, abdominal pain, skin nodules, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy. Mycobacterium genavense was identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) sequencing in skin, duodenal, and rectal biopsies. A regimen of clarithromycin, rifabutin, and ethambutol was started but his symptoms worsened despite intensification of antimicrobial therapy with moxifloxacin, amikacin, and linezolid and negative cultures, leading to concern for IRIS vs disseminated disease.

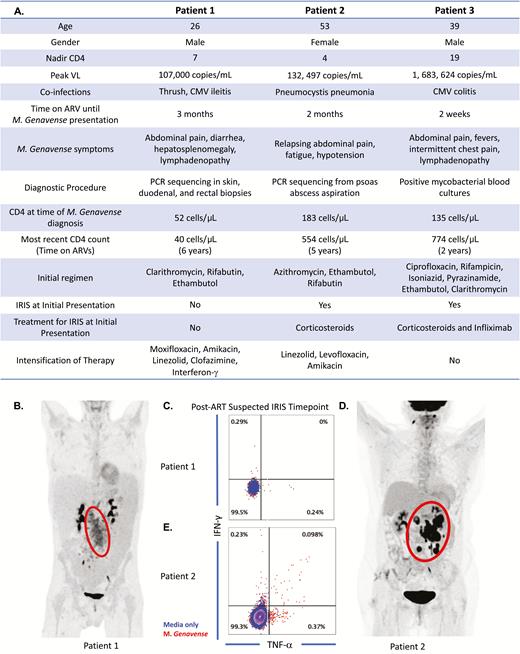

A, Clinical and immunological summaries of patients 1, 2, and 3. B, Protocol mandated abdominal fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan imaging of patient 1 to better visualize inflammation as measured by glucose uptake. C, Tumor necrosis factor and interferon-γ production by CD4 T cells of patient 1 after in vitro stimulation with irradiated Mycobacterium genavense. D, Protocol-mandated abdominal FDG-PET scan imaging of patient 2. E, Cytokine production by CD4 T cells of patient 2 after in vitro stimulation with irradiated M. genavense. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells collected at time of presentation were used for in vitro stimulation with irradiated M. genavense in patients 1 and 2 to detect production of cytokines by CD4 T cells. Patient 1 had no evidence of CD4 T-cell cytokine response as shown (response does not exceed that of media alone or background). In contrast, patient 2 had clear evidence of a CD4 T-cell cytokine response when coincubated with M. genavense with an increased cytokine response compared to background. Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; ARV, antiretroviral; CMV, cytomegalovirus; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; VL, viral load.

He was referred to the NIH 1 year after his initial presentation with M. genavense (CD4 count, 52 cells/µL; viral load [VL] <40 copies/mL). His examination was significant for wasting, thrush, skin nodules, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy. His laboratory tests were notable for pancytopenia, an elevated C-reactive protein at 104.5 mg/L, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate at 87 mm/hour. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scan demonstrated abdominal disease and diffuse lymphadenopathy (Figure 1B). Numerous acid-fast bacilli (AFB) were found on skin, inguinal lymph node, and bone marrow biopsies, as well as duodenal, colon, and rectal biopsies. Specimens remained culture negative after 12 weeks despite addition of mycobactin.

In vitro stimulations of cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells with mycobacterial lysate showed lack of cytokine production by CD4+ T cells (Figure 1C). The vast pathogen load on biopsies after 1 year of therapy, the protracted clinical course, and absent antimycobacterial CD4 responses supported uncontrolled mycobacterial disease and not IRIS. In an attempt to enhance his immune response and optimize the antimycobacterial effect of antibiotics, interferon-γ and clofazimine were added to his regimen. Additional immunodeficiencies were investigated, and whole exome sequencing analysis detected a heterozygous c.310T>C (p.Cys104Arg) missense variant in TNFRSF13B, a gene reported in association with autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive common variable immunodeficiency, but also reported in asymptomatic individuals [11, 12]. One year later, his skin, abdominal pain, and diarrhea had improved and interferon-γ was stopped.

Six years after his initial presentation, he had continued improvement until a relapse of symptoms at the time of publication with Chylous ascites and chylothorax requiring repeated paracentesis. Biopsy of mesenteric lymph nodes demonstrated a granulomatous infiltrate with no positive AFB stain nor growth on mycobacterial culture. Given the clearance of organisms on biopsies, the primary concern was IRIS, and a trial of prednisone was initiated.

Patient 2

A 53-year-old woman with HIV/AIDS (Figure 1A) initially presented with HIV/AIDS in the context of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia requiring prolonged corticosteroid taper complicated by adrenal insufficiency. One year after ART initiation, she presented with intermittent abdominal pain. Duodenal biopsies demonstrated granulomatous inflammation with AFB microorganisms present. The CD4 count was 183 cells/µL and VL was 22 copies/mL; treatment for presumed MAC was deferred pending workup.

She presented 3 months later with abdominal pain, fatigue, and hypotension requiring intensive care. Enlargement of retroperitoneal and mesenteric lymph nodes, some appearing necrotic, was seen on computed tomographic (CT) imaging. MAC IRIS with adrenal insufficiency was suspected and corticosteroids along with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin were started.

Over the next 5 months, she had multiple admissions with similar presentations. A new psoas abscess and soft tissue density in the uncinate process of the pancreatic head were seen on CT. Psoas abscess biopsy revealed AFB-positive necrotizing granulomas without growth in culture. The pancreatic lesion biopsy was nondiagnostic. A repeat psoas abscess aspiration sent for 16S sequencing at the University of Washington identified M. genavense. Her regimen was broadened to linezolid, levofloxacin, amikacin, and ethambutol along with a corticosteroid taper.

At the NIH (CD4 count, 109 cells/μL [12%]; VL <40 copies/mL), CT imaging showed stable mesenteric lymph nodes lesions, and PET/CT scan showed increased uptake in the abdomen/retroperitoneum, right cervical lymph node, and hard palate (Figure 1D). An Esophagogastroduodenoscopy with random biopsies from the stomach and duodenum, bone marrow biopsy, and biopsy of the abdominal mesenteric nodes were negative for granulomas, AFB organisms, and PCR for mycobacteria. Evidence of CD4 T-cell response to M. genavense was seen in vitro (Figure 1E). We concluded that findings were consistent with IRIS and adrenal insufficiency, as opposed to uncontrolled infection. Her regimen was narrowed to azithromycin, ethambutol, and moxifloxacin to limit toxicity and she remained on hydrocortisone with clinical improvement and weight gain.

Two years following her presentation at NIH, she remained virologically suppressed, had resolution of her adenopathy, and was able to stop antibiotics.

Patient 3

A 39-year-old Polish man with HIV/AIDS (Figure 1A) presented with thrush, scattered lymphadenopathy, and elevated aminotransferases. Significant lymphadenopathy with hepatosplenomegaly and bilateral lower lobe consolidation were seen on CT. A fine needle aspirate of an inguinal lymph node was nondiagnostic. The patient was initiated on ART and discharged after 10 days of admission.

Three days later he presented with pleuritic chest pain, fevers, tachycardia, and worsening lymphadenopathy. CD4 count was 135 cells/µL (22%) with a VL of 2665 copies/mL showing immunological and virologic response to ART. Repeat laboratory tests showed pancytopenia and a rise in inflammatory markers. CT imaging showed progressive adenopathy and splenomegaly. Inguinal lymph node biopsy and bone marrow aspirate were positive for AFB and 3 sets of mycobacterial blood cultures were positive. The patient was started on rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, clarithromycin, and ciprofloxacin as empiric mycobacterial treatment pending identification, and prednisolone for management of presumed IRIS.

The patient had progressive adenopathy and splenomegaly without clinical improvement despite broad mycobacterial treatment and corticosteroids. Episodes of clinical instability, high inflammatory markers, and increasing analgesic requirements coincided with steroid tapering. On day 67 of admission, the mycobacterium was identified as M. genavense. Mycobacterial treatment was adjusted to ciprofloxacin, rifampicin, and clarithromycin. Interleukin 6 level was reported as 187 pg/mL which, along with his clinical presentation, virologic suppression, and rise in CD4 count, supported the diagnosis of mycobacterial IRIS.

Given his steroid-refractory clinical course, the decision was made to administer immunomodulatory therapy [13] with an infliximab infusion (5 mg/kg intravenously) on day 80 of admission. Following the infusion, he defervesced, was weaned off opiates, and was discharged 8 days later. He required 3 additional doses of infliximab in addition to his antimycobacterial regimen over 8 months to achieve resolution of his symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Similar to previous reports [6], our HIV and M. genavense patients were lymphopenic with opportunistic infections and presented with abdominal pain and lymphadenopathy, yet still spanned a spectrum of clinical presentations including hematologic, dermatologic, and endocrine manifestations. In only 1 of the 3 patients, M. genavense successfully grew in culture and in the other 2 cases sequencing was used for diagnosis. Due to its fastidious nature, M. genavense is hard to grow and it can be difficult to tell if worsening or protracted symptoms represent IRIS vs lack of immune reconstitution or inappropriate management.

Our 3 clinical presentations highlight the symptomatology spectrum encountered in the ART era as determined by burden of mycobacterial antigen and presence and intensity of immune responses. Patient 1 had minimal CD4 reconstitution, no CD4 mycobacterial specific responses, and an impressive pathogen load 1 year after antimycobacterial therapy, which led us to consider overwhelming infection as the etiology of his course, requiring intensification of therapy. Although it is difficult to ascertain how much his genetic defect played in his mycobacterial infection, we would argue that in similar cases of persistent infection, workup for other underlying immunodeficiencies should be considered and in these cases IRIS may still be a complication at a later time when pathogen load is more contained. In the other 2 cases, proximity of symptoms to ARV initiation along with CD4 restoration and improvement after corticosteroids supported an IRIS diagnosis, further corroborated by evidence of CD4 T-cell responses in patient 2.

These cases highlight the range of presentations of M. genavense in HIV patients in the ARV era, with natural history compounded by either IRIS or poor immune reconstitution requiring either immunosuppressive therapies or additional antimicrobials and immune boosting strategies, respectively, for effective clinical outcomes.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the study participants, the staff of the outpatient clinic 8, and the inpatient ward team.

Disclaimer. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States government.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest. M.-L. V. reports consulting fees from Gilead, Merck, and ViiV, and lecture fees from Gilead and Merck, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References