-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Wing Yee Tong, Chee Fu Yung, Lee Chern Chiew, Siong Beng Chew, Li Duan Ang, Koh Cheng Thoon, Victor S Rajadurai, Kee Thai Yeo, Universal Face Masking Reduces Respiratory Viral Infections Among Inpatient Very-Low-Birthweight Neonatal Infants, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 71, Issue 11, 1 December 2020, Pages 2958–2961, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa555

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We reviewed the impact of a universal face masking policy on respiratory viral infections (RVIs) among admitted very-low-birthweight infants in our neonatal department. There was a significant decrease in RVI incidence, specifically in our step-down level 2 unit, with respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza virus being the most common viruses isolated.

Respiratory viral infections (RVIs) are important causes of clinical deterioration, increased length of inpatient stay, and long-term respiratory morbidity among very-low-birthweight (VLBW) infants [1, 2]. Despite enforcement of infection control practices in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) and nurseries, RVIs and outbreaks are not uncommon [3]. Standard infection control procedures in neonatal units, which focuses on symptomatic caregivers/healthcare personnel, may be insufficient to prevent spread by those with asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic RVI [1].

Medical face masks are used to prevent transmission of diseases that are spread through large respiratory droplets [4]. Recent cohort studies investigating universal face masking in the care of vulnerable pediatric populations have demonstrated significant reductions in RVIs [5, 6]. We evaluated the impact of a universal face masking policy in our neonatal units, as a complement to existing infection prevention strategies, on RVI incidence among VLBW infants.

METHODS

This was an audit to evaluate the effectiveness of universal medical masking in reducing RVIs among VLBW infants (birth weight < 1500 g). We compared the RVI incidence before and after the institution of a universal medical mask policy in our neonatal units in January 2016. Education of caregivers and staff members on this policy was carried out during the first half of 2016.

We included all live-born VLBW infants admitted to KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH) NICU and Special Care Nursery (SCN) (level 2 nursery with no provision of continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula therapy). KKH is the only women’s and children’s public hospital in Singapore, caring for an estimated 11 500 pregnant women and 200 VLBW infants annually. The 40-bed NICU is divided into 4-bed rooms and the 60-bed SCN into two 30-bed open wards.

We compared the RVI incidence 5 years before (premasking: January 2011–December 2015) and 3 years after (postmasking: January 2017–December 2019) the introduction of the universal face masking policy. All staff and visitors are required to wear a disposable, surgical face mask when in clinical areas. Standard infection control and transmission-based precautions were consistently practiced in our units during the audit period [7]. Infants weighing < 1500 g are placed in enclosed incubators, and those ≥ 1500 g with stable, normal temperatures are placed in open bassinets. Children < 16 years of age are barred from the units and all staff/visitors are advised against entering if unwell.

As per department protocol, infants with RVI symptoms (cough, increased respiratory secretions, apnea, temperature ≥38°C) will undergo nasopharyngeal aspirate/swab testing for respiratory viruses via direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) and/or multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, according to physician preference. Viruses detectable by DFA (D3 Double Duet DFA Respiratory Virus Screening and ID Kit; Diagnostic Hybrids) include influenza A, influenza B, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), adenovirus, parainfluenza virus (PIV) 1–3, and human metapneumovirus (HMPV). The multiplex PCR kit used (Seeplex RV15 ACE detection kit; Seegene, South Korea) could detect additional viruses: PIV-4, coronavirus 229E, coronavirus OC43, bocavirus, rhinovirus, and enterovirus. Quarter-year, cross-department, random hand hygiene compliance audits conducted in the department were analyzed. Results of a survey conducted in May 2017 on self-reported face masking compliance among our department staff were reported.

RVI incidence was calculated based on the location where the infection was detected—as a proportion of the total VLBW infants admitted to the unit and also expressed per 1000 patient-days. Analysis was performed by comparing the premasking and postmasking periods, using χ 2 for proportions, Mann-Whitney U test for comparison of medians, and Fisher exact test for rates, as appropriate. This audit did not require formal institutional review board review and was conducted in compliance with institutional policies, regulations, and guidelines.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 1767 and 1549 VLBW infants were admitted to the NICU and SCN, respectively, during the audit period. Of the 45 VLBW infants (2.5%) with RVI, 28 were male (62%). The median birth gestational age of infected infants was 27 (interquartile range [IQR], 3) weeks, and the median birth weight was 870 (IQR, 346) g. Gestational age and birth weight were similar in the premasking compared to the postmasking period (median, 27 [IQR, 3] weeks vs 26 [IQR, 2] weeks, P = .9; median, 888 [IQR, 343] g vs 835 [IQR, 200] g, P = .5). The median postnatal age of RVIs was 103 days (IQR, 53), with similar age of infection in the pre- and postmasking periods (104 [IQR, 59] days vs 100 [IQR, 50] days; P = .8).

Impact of Universal Masking Policy

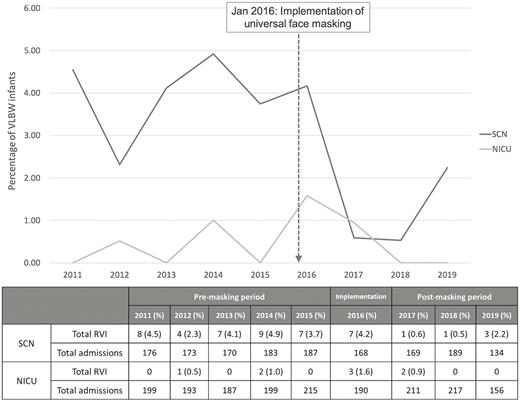

Figure 1 illustrates RVI trend over the audit period, stratified by patient location at time of diagnosis. The majority of RVIs occurred in the SCN (40/45 [89%] VLBW infants). There was a decrease in RVIs after implementation of the universal masking policy, from 38 to 7 infections. This reduction was significant in the SCN, from 35 RVIs in premasking period to 5 RVIs in the postmasking period (3.9% to 1.0%; P = .001), and a decrease from 1.1 to 0.3 per 1000 patient-days (P = .008). In the NICU, there were 3 (0.3%) and 2 (0.3%) infections from the premasking to postmasking periods (0.07 and 0.09 per 1000 patient-days, respectively; P = 1.0).

Incidence of respiratory viral infections, by year. Abbreviations: NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; RVI, respiratory viral infection; SCN, special care nursery; VLBW, very low birth weight.

Viral Pathogens

RSV (25%), PIV (21%), and rhinovirus (17%) accounted for almost two-third of RVIs. Other viruses detected enterovirus (17%), influenza (8%), adenovirus (6%), and HMPV (6%). Three infants had viral coinfections. During the premasking period, RSV was the most common virus isolated (10/41 [24%]), whereas rhinovirus was most common in the postmasking period (3/7 [43%]). Almost all PIV infections were detected during the premasking period, decreasing from 9 of 41 (22%) to 1 of 7 (14%) viruses detected over the 2 periods.

In the NICU, only 5 RVIs were detected: 3 premasking (2 RSV, 1 adenovirus) and 2 postmasking (2 rhinovirus). In SCN, the most common virus detected in the premasking period was PIV (9/38 [24%]) and in the postmasking period was RSV (2/5 [40%]). The RVI distribution between the 2 SCN wards across the 2 time periods was not different (22 and 18 RVIs in ward 1 and ward 2, respectively; P = .2). There was also a trend toward increased PCR testing: 18 of 38 (47%) premasking compared to 5 of 7 (71%) postmasking (P = .4; Supplementary Table 1).

Infection Control Procedures and Compliance

The median hand hygiene compliance rate in NICU and SCN over the 2 periods was 96% (IQR, 3) and 96% (IQR, 5), respectively (P = .2). Although the overall compliance rates were high, we noted a significantly lower rate in the SCN postmasking period compared to premasking (93% [IQR, 3] vs 97% [IQR, 4]; P = .003). There was no difference in the NICU for both time periods. An anonymous survey of 180 neonatal staff on self-reported face masking behavior reported compliance of 94%.

DISCUSSION

Limited observational studies in neonatal units have documented significant variability in RVI prevalence, ranging from 1%–8% [8, 9] to 30%–50% [10]. A recent study in our unit estimated that 1.7% of VLBW infants acquired an RVI during their birth admission [11]. Standard neonatal infection control measures comprised of hand hygiene, seasonal influenza vaccination of staff members, and isolation of symptomatic patients do not address the potential shedding of respiratory viruses in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic caregivers or staff. With increased adoption of initiatives to increase parental involvement in the care of VLBW infants in the NICU and nurseries [12], there are concerns of increased risk of spread of respiratory viruses [1].

In this audit, we demonstrated that universal face masking significantly reduced the RVI prevalence among VLBW infants, specifically in our step-down level 2 nursery. There was an almost 4-fold reduction in RVIs from the pre- to postmasking period. This was despite a documented decrease in hand hygiene compliance rate in the SCN area during the masking period, although overall compliance was still high. The different setups in NICU and SCN could have accounted for the different effect of facial masking on RVI transmission. In the nursery, infants are typically nursed in open bassinets, which renders them more vulnerable to contact with droplets from infected individuals. By comparison, infants in NICU are placed in incubators, which act as barriers, diminishing the effect of face masking.

RSV, PIV, and rhinovirus were the most common causes of RVI in our VLBW population. Consistent with reports from pediatric stem cell transplant patients, we noted reduction in PIV infections among our VLBW population after implementation of universal masking policy. This is possibly due to the mitigation of transmission risk from caregivers and healthcare workers, who are more likely to be asymptomatic with PIV infections [5].

There were several limitations to this audit. Restricting testing to symptomatic infants may have missed those who were asymptomatic or had atypical symptoms. The nonstandardized usage of DFA and PCR for RVI diagnosis could have impacted viral detection due to differences in sensitivity and virus coverage. However, with the shift to the more sensitive PCR testing in recent times, the persistence of lower RVI incidence strengthens our finding. The implementation of a universal face masking policy may also have increased staff awareness and adherence to standard and transmission-based precautions for patient care, but adherence to these are not routinely audited for analysis. Last, we could only report data for 3 years after the implementation of universal masking policy, but the longer premasking period should reduce the bias from regression to the mean.

In summary, a universal face masking policy is an inexpensive and potentially effective method to reduce the incidence of RVIs among VLBW infants in high risk settings such as nurseries with open ward settings.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. W. Y. T. performed the analysis and interpretation of the data and drafted the initial manuscript. C. F. Y., L. C. C., S. B. C., L. D. A., K. C. T., and V. S. R. were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data and reviewed and critically revised the manuscript. K. T. Y. designed the study, was involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data, and reviewed and critically revised the manuscript. He had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for submission for publication. All authors approved the manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments. The authors acknowledge the contributions of the late Dr Manuel Joseph Gomez in the implementation of the universal face masking initiative. The authors also acknowledge the doctors and nurses of the KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital neonatal department who contributed to the implementation of this policy.

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.