-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sumanth Gandra, Eili Y. Klein, Suraj Pant, Surbhi Malhotra-Kumar, Ramanan Laxminarayan, Faropenem Consumption is Increasing in India, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 62, Issue 8, 15 April 2016, Pages 1050–1052, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw055

Close - Share Icon Share

To the Editor—India has among the highest rates of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)–producing Enterobacteriaceae organisms in the world [1]. Carbapenems are a reliable treatment option for serious infections caused by ESBL-producing organisms [2], but the need for intravenous administration and high costs make them less suitable for outpatient therapy. In India, an alternative that is often prescribed by clinicians is faropenem, an oral antibiotic that belongs to the “penems” class of β-lactam antibiotics. Penems are a hybrid of penam (penicillin) and cepham (cephalosporins) nuclei and are structurally most similar to carbapenems [3].

Faropenem has broad antimicrobial activity, is active against aerobic gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria, and is also resistant to TEM-, SHV-, and CTX-M–type ESBLs [3]. In India, faropenem is approved for the treatment of respiratory tract, urinary tract, skin, soft-tissue, and gynecological infections [4]. It is often used to treat invasive ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae infections even though its efficacy in these cases is not clinically proved.

We used data from IMS Health and methods described elsewhere [5], to analyze the consumption of faropenem in India, measured in standard units (the number of doses sold) [5]. The standard unit is a measure of volume based on an assumption about the smallest identifiable dose, depending on the pharmaceutical form given to a patient.

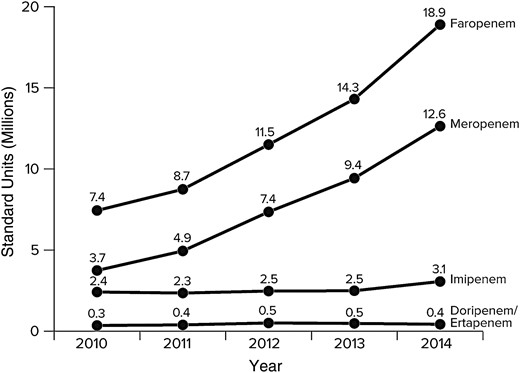

We found that faropenem consumption increased by 154% since it was approved in 2010 (from 7.4 million standard units in 2010 to 18.9 million standard units in 2014) (Figure 1). Though meropenem consumption also increased from 2010 to 2014, faropenem consumption exceeded total carbepenem (meropenem, imipenem, ertapenem, and doripenem) consumption in India (Figure 1).

Trends in faropenem and carbapenem consumption in India, 2010–2014. Data from IMS Health (prescription data, January 2010 to December 2014); the statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed herein are not necessarily those of IMS Health or any of its affiliated or subsidiary entities.

The sharp increase in consumption of faropenem poses a concern because of the potential for cross-resistance to carbapenems. Presently, susceptibility testing against faropenem is not routinely performed in microbiology laboratories in India owing to lack of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute or European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing guidelines because the drug has not been approved in the United States or Europe. Recent in vitro studies have shown that faropenem could be a screening indicator of carbapenemase activity in an organism [6]. More than 99% of carbapenemase producers tested show growth up to the edge of a faropenem disk (in contrast to carbapenems tested, which showed inhibition zones) [6]. This feature makes it a convenient antibiotic to screen for carbapenemase producers, but it may be indicative of a lower activity of faropenem against such strains or of a higher induction of the carbapenemase by faropenem [6].

With carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae already highly prevalent in India [1] and our current lack of understanding regarding rates of resistance and the selection potential of faropenem as well as cross-resistance with carbapenems, immediate measures are needed to limit its use. In the long term, this investment will help prolong the activity of one of our major and possibly last-resort antibiotic groups.

Notes

Financial support. The work is supported by the ResistanceMap (S. G. and R. L.) and Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership (S. P. and R. L.) projects, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.