-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Andrew Hill, Mark J Siedner, Cassandra Fairhead, Francois Venter, The Need for Lenacapavir Compulsory Licences in Ending the HIV Epidemic, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2025;, ciaf115, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaf115

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In total, 1.3 million people acquired human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in 2023, well behind the UNAIDS goal of <370 000 infections by 2025. Novel 6-monthly injectable pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medication lenacapavir is highly efficacious and could be epidemic-changing. However, without equitable access infection rates will continue. Gilead Sciences, the originator, currently charges over $40 000 per person-year for lenacapavir as HIV treatment, far exceeding PrEP cost-effectiveness thresholds, even in the richest countries. Yet the projected cost of production at scale is <$100 per person-year. Gilead's new voluntary license for lenacapavir prevention and treatment undermines access. Middle-income countries with fast-growing HIV epidemics have been excluded; 23% of new HIV infections occur in these countries. A coordinated response from governments, donors, civil society, and the private sector including Gilead is urgently required to ensure lenacapavir access is wide enough to eliminate HIV transmission worldwide. Unless crucial changes to the current license are made, compulsory licences may be required.

Despite numerous effective strategies to prevent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission, there were 1.3 million new HIV infections globally in 2023 [1]. Although incidence is falling in many places, this is happening far too slowly to meet UNAIDS targets and for several years progress has begun to stall [1]. Alarmingly, in other parts of the world, new infection rates continue to rise. Certain regions and groups remain at particularly high risk: according to UNAIDS over 3000 women in sub-Saharan Africa acquire HIV each week alone [2]. Additional options to prevent HIV transmission are urgently needed. There was therefore great excitement in July 2024 when the full results of the PURPOSE-1 trial for the novel long-acting pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medication lenacapavir were announced. Among 2134 female participants with a 2.3% background risk of HIV infection, none acquired HIV while taking 6-monthly injections of lenacapavir [3]. In the comparator arms, 55/3204 women taking conventional oral PrEP acquired HIV [3]. The results were so striking that the trial was stopped early for efficacy, and Gilead has offered all participants in both arms lenacapavir. In September 2024 a similar result was seen for men who have sex with men and transgender people in the PURPOSE-2 trial, where background HIV incidence was 2.4% [4]. This trial was also stopped early after an 89% reduction in HIV transmission was demonstrated compared with oral PrEP [4].

Potential of Long-acting Injectables for HIV Prevention in High-risk Populations

Lenacapavir is the closest we have ever been to a highly effective HIV vaccine: a 6-monthly injection, and, unlike prior vaccine candidates, this reduces infection risk to almost zero. Long-acting forms of PrEP like lenacapavir or cabotegravir can be given discreetly, for example, in family planning clinics or possibly integrated with hormonal contraception services, which may reduce the risk of stigma. Long-acting formulations also prevent the need for daily pill-taking. There is evidence that this can improve adherence, particularly in high-risk populations with structural barriers to healthcare access [5].

In PURPOSE-1 and 2 the number needed to treat to prevent 1 case of HIV in high-risk individuals was approximately 40. Thus, many millions of people will need to be provided access to this drug to markedly reduce global infections. Gilead currently charges over $40 000 per person-year for lenacapavir for the treatment of HIV in North America and Europe [6]. According to some estimates, that price would need to be reduced to less than an estimated $100 per person-year to be cost-effective in low- and middle-income (LMIC) contexts [7]. Lenacapavir's estimated initial cost of production is $100 per person-year, and as low as $40 per person-year as production increases [6]. By comparison oral PrEP, which is highly effective in some populations, is off-patent and cheap generics are therefore already available in most countries for prices as low as $40 per person-year [8]. However, numerous trials, including the VOICE study and PURPOSE 1 and 2, have demonstrated that oral PrEP is not a highly effective solution for many of the populations at highest risk for HIV infection [3, 4, 9].

Barriers to Access for Lenacapavir

Patents are historically barriers to equitable access for LMICs, where essential medicines are priced well beyond broad access until generic production is possible [10]. Where technologies are still under patent, voluntary licenses have been an important mechanism to ensure access to key drugs for infectious diseases at affordable prices. Worldwide, over 25 million people are taking generic antiretrovirals as part of voluntary licensing systems [11].

However, Gilead has opted not to use the services of the not-for-profit Medicines Patent Pool (MPP), a proven public health voluntary licensing system used in recent decades for licensing of antiretrovirals (including of Gilead's products), to make lenacapavir widely available. This is despite having previously licensed 6 HIV medicines to MPP, and despite a recent voluntary licence between ViiV and the MPP for long-acting cabotegravir PrEP [12, 13]. Instead, in October, Gilead announced a “direct” and “royalty free” voluntary license for lenacapavir [14, 15]. This agreement will allow 6 generic companies to mass-produce lenacapavir for LMICs. Gilead's stated objective was to supply lenacapavir to “high incidence, resource-limited” countries [14].

However, Gilead's new voluntary license includes stipulations that could undermine the potential of lenacapavir to support HIV prevention. Some concerns are summarized in Table 1.

Summary of Key Concerns in Gilead's Voluntary Licence Which Could Undermine the Potential of Lenacapavir to Support HIV Prevention

| 1 | Countries with high HIV incidence excluded | The voluntary licence excludes middle-income countries with fast-growing HIV epidemics and key population incidence higher than the PURPOSE-1/2 trials. |

| 2 | Countries with low GNI excluded | The voluntary licence excludes countries which have lower GNI compared to included countries, and no clear definition of “high incidence, resource-limited countries” is provided. |

| 3 | Declaration of Helsinki violated* | The voluntary licence excludes countries from which PURPOSE-2 recruited including Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, and Peru, violating the Declaration of Helsinki. |

| 4 | Access for excluded countries further restricted | Diversion clauses prohibit supply to excluded countries which issue compulsory licences, or to countries where no patent has been filed. |

| 5 | Potential for lenacapavir as treatment is restricted | Approved therapeutic uses of lenacapavir beyond treatment in “heavily treatment-experienced patients” (a very small group of patients) and investigation of co-formulations is prohibited. |

| 6 | Potential for combinations is restricted | Combination products or co-packaging with partner antiretroviral drugs is prohibited. |

| 7 | Key generic manufacturers are left out | Only six generic suppliers are included, compromising scale-up. Widespread generic availability is not projected to occur until 2028. |

| 8 | Generic manufacturers' ability to import materials to produce lenacapavir is restricted | The voluntary licence limits the import of Key Starting Materials necessary for the production of lenacapavir Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient, such that only Gilead or included manufacturers can supply these. This could delay scale-up and cause the needs of HICs (that will be supplied by Gilead) to be prioritized over the needs of LMICs (that will be served by licensees), despite the greatest HIV transmission burden being in LMICs. |

| 1 | Countries with high HIV incidence excluded | The voluntary licence excludes middle-income countries with fast-growing HIV epidemics and key population incidence higher than the PURPOSE-1/2 trials. |

| 2 | Countries with low GNI excluded | The voluntary licence excludes countries which have lower GNI compared to included countries, and no clear definition of “high incidence, resource-limited countries” is provided. |

| 3 | Declaration of Helsinki violated* | The voluntary licence excludes countries from which PURPOSE-2 recruited including Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, and Peru, violating the Declaration of Helsinki. |

| 4 | Access for excluded countries further restricted | Diversion clauses prohibit supply to excluded countries which issue compulsory licences, or to countries where no patent has been filed. |

| 5 | Potential for lenacapavir as treatment is restricted | Approved therapeutic uses of lenacapavir beyond treatment in “heavily treatment-experienced patients” (a very small group of patients) and investigation of co-formulations is prohibited. |

| 6 | Potential for combinations is restricted | Combination products or co-packaging with partner antiretroviral drugs is prohibited. |

| 7 | Key generic manufacturers are left out | Only six generic suppliers are included, compromising scale-up. Widespread generic availability is not projected to occur until 2028. |

| 8 | Generic manufacturers' ability to import materials to produce lenacapavir is restricted | The voluntary licence limits the import of Key Starting Materials necessary for the production of lenacapavir Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient, such that only Gilead or included manufacturers can supply these. This could delay scale-up and cause the needs of HICs (that will be supplied by Gilead) to be prioritized over the needs of LMICs (that will be served by licensees), despite the greatest HIV transmission burden being in LMICs. |

[14] *Section 20, Declaration of Helsinki, 2024: “Medical research with individuals, groups, or communities in situations of particular vulnerability is only justified if it is responsive to their health needs and priorities and the individual, group, or community stands to benefit from the resulting knowledge, practices, or interventions. Researchers should only include those in situations of particular vulnerability when the research cannot be carried out in a less vulnerable group or community, or when excluding them would perpetuate or exacerbate their disparities” [16].

Abbreviations: GNI, gross national income; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LMIC, low- and middle-income countries.

Summary of Key Concerns in Gilead's Voluntary Licence Which Could Undermine the Potential of Lenacapavir to Support HIV Prevention

| 1 | Countries with high HIV incidence excluded | The voluntary licence excludes middle-income countries with fast-growing HIV epidemics and key population incidence higher than the PURPOSE-1/2 trials. |

| 2 | Countries with low GNI excluded | The voluntary licence excludes countries which have lower GNI compared to included countries, and no clear definition of “high incidence, resource-limited countries” is provided. |

| 3 | Declaration of Helsinki violated* | The voluntary licence excludes countries from which PURPOSE-2 recruited including Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, and Peru, violating the Declaration of Helsinki. |

| 4 | Access for excluded countries further restricted | Diversion clauses prohibit supply to excluded countries which issue compulsory licences, or to countries where no patent has been filed. |

| 5 | Potential for lenacapavir as treatment is restricted | Approved therapeutic uses of lenacapavir beyond treatment in “heavily treatment-experienced patients” (a very small group of patients) and investigation of co-formulations is prohibited. |

| 6 | Potential for combinations is restricted | Combination products or co-packaging with partner antiretroviral drugs is prohibited. |

| 7 | Key generic manufacturers are left out | Only six generic suppliers are included, compromising scale-up. Widespread generic availability is not projected to occur until 2028. |

| 8 | Generic manufacturers' ability to import materials to produce lenacapavir is restricted | The voluntary licence limits the import of Key Starting Materials necessary for the production of lenacapavir Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient, such that only Gilead or included manufacturers can supply these. This could delay scale-up and cause the needs of HICs (that will be supplied by Gilead) to be prioritized over the needs of LMICs (that will be served by licensees), despite the greatest HIV transmission burden being in LMICs. |

| 1 | Countries with high HIV incidence excluded | The voluntary licence excludes middle-income countries with fast-growing HIV epidemics and key population incidence higher than the PURPOSE-1/2 trials. |

| 2 | Countries with low GNI excluded | The voluntary licence excludes countries which have lower GNI compared to included countries, and no clear definition of “high incidence, resource-limited countries” is provided. |

| 3 | Declaration of Helsinki violated* | The voluntary licence excludes countries from which PURPOSE-2 recruited including Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, and Peru, violating the Declaration of Helsinki. |

| 4 | Access for excluded countries further restricted | Diversion clauses prohibit supply to excluded countries which issue compulsory licences, or to countries where no patent has been filed. |

| 5 | Potential for lenacapavir as treatment is restricted | Approved therapeutic uses of lenacapavir beyond treatment in “heavily treatment-experienced patients” (a very small group of patients) and investigation of co-formulations is prohibited. |

| 6 | Potential for combinations is restricted | Combination products or co-packaging with partner antiretroviral drugs is prohibited. |

| 7 | Key generic manufacturers are left out | Only six generic suppliers are included, compromising scale-up. Widespread generic availability is not projected to occur until 2028. |

| 8 | Generic manufacturers' ability to import materials to produce lenacapavir is restricted | The voluntary licence limits the import of Key Starting Materials necessary for the production of lenacapavir Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient, such that only Gilead or included manufacturers can supply these. This could delay scale-up and cause the needs of HICs (that will be supplied by Gilead) to be prioritized over the needs of LMICs (that will be served by licensees), despite the greatest HIV transmission burden being in LMICs. |

[14] *Section 20, Declaration of Helsinki, 2024: “Medical research with individuals, groups, or communities in situations of particular vulnerability is only justified if it is responsive to their health needs and priorities and the individual, group, or community stands to benefit from the resulting knowledge, practices, or interventions. Researchers should only include those in situations of particular vulnerability when the research cannot be carried out in a less vulnerable group or community, or when excluding them would perpetuate or exacerbate their disparities” [16].

Abbreviations: GNI, gross national income; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LMIC, low- and middle-income countries.

As such, despite Gilead having made public claims of having “good participatory practice representing the voice of the people most disproportionately affected by HIV and currently underserved for PrEP” [17], the scope of the licence has been criticized or opposed by leading organizations working on HIV. Examples of these critiques are summarized in Table 2.

Criticisms of Gilead's Voluntary Licence and Access Arrangements From Leading HIV Organisations

| Organization . | Criticism of Gilead's Lenacapavir Voluntary Licence . |

|---|---|

| UNAIDS [18] | “The exclusion of many middle-income countries from the licence is deeply worrying and undermines the potential of this scientific breakthrough” − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price and costs − Criticism of exclusion of middle-income countries, highlighting high incidence in these regions − Exclusion of South Africa-based generic companies − Criticism of limiting treatment to “heavily treatment-experienced patients” |

| MSF [19] | Current pricing for lenacapavir as treatment “undermines the potential of this scientific breakthrough and slows the global effort to turn the tide on HIV and AIDS.” − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price and costs − Advocates for generic supply to all LMICs − Advocates for VL through the MPP |

| Unitaid [20] | “Countries and populations with high, growing, concentrated HIV epidemics—including countries that have led foundational work to make PrEP a reality, like Brazil—cannot be excluded from licensing agreements, and registration plans” − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price |

| International AIDS Society [21] | “many countries with high HIV incidence are not included in the licensing arrangements, which will slow access” − Criticism of exclusion of high-incidence countries − Criticism of exclusion of PURPOSE-2 countries |

| Statement signed by 31 HIV advocacy organisation sin Africa, coordinate by KELIN Kenya [22] | “No country should be left behind in access to life-saving medicines.” − Criticism of exclusion of countries from the voluntary licence, particularly Algeria and low- and middle-income countries in South America and Asia − Criticism of limiting generic manufacturers to six with only one in Africa as undermining regional self-sufficiency − Criticism of diversion clauses |

| International Treatment Preparedness Coalition [23] | “Gilead's voluntary license (VL) will prevent millions of people especially key populations from accessing LEN.” − Criticism of exclusion on MICs in South America − Criticism of VL's potential to worsen global health inequity − Criticism of diversion clauses − Criticism of limiting generic manufacturers to six as undermining local manufacturing capacity, regional self-sufficiency and long-term sustainability, particularly in Africa, Eastern Europe and Central Asia |

| Health Justice Initiative [24] | “Governments should take compulsory measures [against Gilead] to ensure two things: generics, everywhere in the world…and affordable, transparent prices…” − Criticism of exclusion of countries from the voluntary licence − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price |

| AIDS Healthcare Foundation Brazil [25] | “key HIV-affected countries excluded from the deal—particularly those in Latin America and others—must also have affordable access to this breakthrough treatment” − Criticism of exclusion of MICs, particularly in South America − Criticism of exclusion of generic manufacturers as undermining local manufacturing capacity and regional self-sufficiency, particularly in South Africa − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price |

| ACT-UP [26] | “If this licence included all low- and middle-income countries it would allow other manufacturers to produce the drug, helping bring the price down through generic competition whilst also enabling greater supply to meet demand and ultimately help to end new HIV transmissions” − Criticism of lack of engagement with MPP |

| Treatment Action Group [27] | “it still leaves far too many behind” − Criticism of exclusion of middle-income counties − Criticism of diversion clauses − Criticism of exclusion of PURPOSE-2 countries − Criticism of the current price of lenacapavir as treatment |

| HealthGAP [28] | “Gilead's access strategy for lenacapavir will unnecessarily prolong the HIV pandemic” − Advocated for inclusion of all LMICs − Criticism of Gilead's unilateral control of supply and price − Criticism of exclusion of PURPOSE-2 countries as unethical − Criticism of diversion clauses |

| People's Medicines Alliance [29] | “This exciting news is marred by Gilead's refusal to work with the UN-backed Medicines Patent Pool to license a generic version of this medicine for developing countries.” − Criticism of exclusion of MICs − Criticism of lack of transparency in definition of “high-incidence resource-limited” countries − Criticism of lack of transparency on price |

| Organization . | Criticism of Gilead's Lenacapavir Voluntary Licence . |

|---|---|

| UNAIDS [18] | “The exclusion of many middle-income countries from the licence is deeply worrying and undermines the potential of this scientific breakthrough” − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price and costs − Criticism of exclusion of middle-income countries, highlighting high incidence in these regions − Exclusion of South Africa-based generic companies − Criticism of limiting treatment to “heavily treatment-experienced patients” |

| MSF [19] | Current pricing for lenacapavir as treatment “undermines the potential of this scientific breakthrough and slows the global effort to turn the tide on HIV and AIDS.” − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price and costs − Advocates for generic supply to all LMICs − Advocates for VL through the MPP |

| Unitaid [20] | “Countries and populations with high, growing, concentrated HIV epidemics—including countries that have led foundational work to make PrEP a reality, like Brazil—cannot be excluded from licensing agreements, and registration plans” − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price |

| International AIDS Society [21] | “many countries with high HIV incidence are not included in the licensing arrangements, which will slow access” − Criticism of exclusion of high-incidence countries − Criticism of exclusion of PURPOSE-2 countries |

| Statement signed by 31 HIV advocacy organisation sin Africa, coordinate by KELIN Kenya [22] | “No country should be left behind in access to life-saving medicines.” − Criticism of exclusion of countries from the voluntary licence, particularly Algeria and low- and middle-income countries in South America and Asia − Criticism of limiting generic manufacturers to six with only one in Africa as undermining regional self-sufficiency − Criticism of diversion clauses |

| International Treatment Preparedness Coalition [23] | “Gilead's voluntary license (VL) will prevent millions of people especially key populations from accessing LEN.” − Criticism of exclusion on MICs in South America − Criticism of VL's potential to worsen global health inequity − Criticism of diversion clauses − Criticism of limiting generic manufacturers to six as undermining local manufacturing capacity, regional self-sufficiency and long-term sustainability, particularly in Africa, Eastern Europe and Central Asia |

| Health Justice Initiative [24] | “Governments should take compulsory measures [against Gilead] to ensure two things: generics, everywhere in the world…and affordable, transparent prices…” − Criticism of exclusion of countries from the voluntary licence − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price |

| AIDS Healthcare Foundation Brazil [25] | “key HIV-affected countries excluded from the deal—particularly those in Latin America and others—must also have affordable access to this breakthrough treatment” − Criticism of exclusion of MICs, particularly in South America − Criticism of exclusion of generic manufacturers as undermining local manufacturing capacity and regional self-sufficiency, particularly in South Africa − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price |

| ACT-UP [26] | “If this licence included all low- and middle-income countries it would allow other manufacturers to produce the drug, helping bring the price down through generic competition whilst also enabling greater supply to meet demand and ultimately help to end new HIV transmissions” − Criticism of lack of engagement with MPP |

| Treatment Action Group [27] | “it still leaves far too many behind” − Criticism of exclusion of middle-income counties − Criticism of diversion clauses − Criticism of exclusion of PURPOSE-2 countries − Criticism of the current price of lenacapavir as treatment |

| HealthGAP [28] | “Gilead's access strategy for lenacapavir will unnecessarily prolong the HIV pandemic” − Advocated for inclusion of all LMICs − Criticism of Gilead's unilateral control of supply and price − Criticism of exclusion of PURPOSE-2 countries as unethical − Criticism of diversion clauses |

| People's Medicines Alliance [29] | “This exciting news is marred by Gilead's refusal to work with the UN-backed Medicines Patent Pool to license a generic version of this medicine for developing countries.” − Criticism of exclusion of MICs − Criticism of lack of transparency in definition of “high-incidence resource-limited” countries − Criticism of lack of transparency on price |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LMIC, low- and middle-income countries; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

Criticisms of Gilead's Voluntary Licence and Access Arrangements From Leading HIV Organisations

| Organization . | Criticism of Gilead's Lenacapavir Voluntary Licence . |

|---|---|

| UNAIDS [18] | “The exclusion of many middle-income countries from the licence is deeply worrying and undermines the potential of this scientific breakthrough” − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price and costs − Criticism of exclusion of middle-income countries, highlighting high incidence in these regions − Exclusion of South Africa-based generic companies − Criticism of limiting treatment to “heavily treatment-experienced patients” |

| MSF [19] | Current pricing for lenacapavir as treatment “undermines the potential of this scientific breakthrough and slows the global effort to turn the tide on HIV and AIDS.” − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price and costs − Advocates for generic supply to all LMICs − Advocates for VL through the MPP |

| Unitaid [20] | “Countries and populations with high, growing, concentrated HIV epidemics—including countries that have led foundational work to make PrEP a reality, like Brazil—cannot be excluded from licensing agreements, and registration plans” − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price |

| International AIDS Society [21] | “many countries with high HIV incidence are not included in the licensing arrangements, which will slow access” − Criticism of exclusion of high-incidence countries − Criticism of exclusion of PURPOSE-2 countries |

| Statement signed by 31 HIV advocacy organisation sin Africa, coordinate by KELIN Kenya [22] | “No country should be left behind in access to life-saving medicines.” − Criticism of exclusion of countries from the voluntary licence, particularly Algeria and low- and middle-income countries in South America and Asia − Criticism of limiting generic manufacturers to six with only one in Africa as undermining regional self-sufficiency − Criticism of diversion clauses |

| International Treatment Preparedness Coalition [23] | “Gilead's voluntary license (VL) will prevent millions of people especially key populations from accessing LEN.” − Criticism of exclusion on MICs in South America − Criticism of VL's potential to worsen global health inequity − Criticism of diversion clauses − Criticism of limiting generic manufacturers to six as undermining local manufacturing capacity, regional self-sufficiency and long-term sustainability, particularly in Africa, Eastern Europe and Central Asia |

| Health Justice Initiative [24] | “Governments should take compulsory measures [against Gilead] to ensure two things: generics, everywhere in the world…and affordable, transparent prices…” − Criticism of exclusion of countries from the voluntary licence − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price |

| AIDS Healthcare Foundation Brazil [25] | “key HIV-affected countries excluded from the deal—particularly those in Latin America and others—must also have affordable access to this breakthrough treatment” − Criticism of exclusion of MICs, particularly in South America − Criticism of exclusion of generic manufacturers as undermining local manufacturing capacity and regional self-sufficiency, particularly in South Africa − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price |

| ACT-UP [26] | “If this licence included all low- and middle-income countries it would allow other manufacturers to produce the drug, helping bring the price down through generic competition whilst also enabling greater supply to meet demand and ultimately help to end new HIV transmissions” − Criticism of lack of engagement with MPP |

| Treatment Action Group [27] | “it still leaves far too many behind” − Criticism of exclusion of middle-income counties − Criticism of diversion clauses − Criticism of exclusion of PURPOSE-2 countries − Criticism of the current price of lenacapavir as treatment |

| HealthGAP [28] | “Gilead's access strategy for lenacapavir will unnecessarily prolong the HIV pandemic” − Advocated for inclusion of all LMICs − Criticism of Gilead's unilateral control of supply and price − Criticism of exclusion of PURPOSE-2 countries as unethical − Criticism of diversion clauses |

| People's Medicines Alliance [29] | “This exciting news is marred by Gilead's refusal to work with the UN-backed Medicines Patent Pool to license a generic version of this medicine for developing countries.” − Criticism of exclusion of MICs − Criticism of lack of transparency in definition of “high-incidence resource-limited” countries − Criticism of lack of transparency on price |

| Organization . | Criticism of Gilead's Lenacapavir Voluntary Licence . |

|---|---|

| UNAIDS [18] | “The exclusion of many middle-income countries from the licence is deeply worrying and undermines the potential of this scientific breakthrough” − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price and costs − Criticism of exclusion of middle-income countries, highlighting high incidence in these regions − Exclusion of South Africa-based generic companies − Criticism of limiting treatment to “heavily treatment-experienced patients” |

| MSF [19] | Current pricing for lenacapavir as treatment “undermines the potential of this scientific breakthrough and slows the global effort to turn the tide on HIV and AIDS.” − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price and costs − Advocates for generic supply to all LMICs − Advocates for VL through the MPP |

| Unitaid [20] | “Countries and populations with high, growing, concentrated HIV epidemics—including countries that have led foundational work to make PrEP a reality, like Brazil—cannot be excluded from licensing agreements, and registration plans” − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price |

| International AIDS Society [21] | “many countries with high HIV incidence are not included in the licensing arrangements, which will slow access” − Criticism of exclusion of high-incidence countries − Criticism of exclusion of PURPOSE-2 countries |

| Statement signed by 31 HIV advocacy organisation sin Africa, coordinate by KELIN Kenya [22] | “No country should be left behind in access to life-saving medicines.” − Criticism of exclusion of countries from the voluntary licence, particularly Algeria and low- and middle-income countries in South America and Asia − Criticism of limiting generic manufacturers to six with only one in Africa as undermining regional self-sufficiency − Criticism of diversion clauses |

| International Treatment Preparedness Coalition [23] | “Gilead's voluntary license (VL) will prevent millions of people especially key populations from accessing LEN.” − Criticism of exclusion on MICs in South America − Criticism of VL's potential to worsen global health inequity − Criticism of diversion clauses − Criticism of limiting generic manufacturers to six as undermining local manufacturing capacity, regional self-sufficiency and long-term sustainability, particularly in Africa, Eastern Europe and Central Asia |

| Health Justice Initiative [24] | “Governments should take compulsory measures [against Gilead] to ensure two things: generics, everywhere in the world…and affordable, transparent prices…” − Criticism of exclusion of countries from the voluntary licence − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price |

| AIDS Healthcare Foundation Brazil [25] | “key HIV-affected countries excluded from the deal—particularly those in Latin America and others—must also have affordable access to this breakthrough treatment” − Criticism of exclusion of MICs, particularly in South America − Criticism of exclusion of generic manufacturers as undermining local manufacturing capacity and regional self-sufficiency, particularly in South Africa − Criticism of Gilead's lack of transparency on price |

| ACT-UP [26] | “If this licence included all low- and middle-income countries it would allow other manufacturers to produce the drug, helping bring the price down through generic competition whilst also enabling greater supply to meet demand and ultimately help to end new HIV transmissions” − Criticism of lack of engagement with MPP |

| Treatment Action Group [27] | “it still leaves far too many behind” − Criticism of exclusion of middle-income counties − Criticism of diversion clauses − Criticism of exclusion of PURPOSE-2 countries − Criticism of the current price of lenacapavir as treatment |

| HealthGAP [28] | “Gilead's access strategy for lenacapavir will unnecessarily prolong the HIV pandemic” − Advocated for inclusion of all LMICs − Criticism of Gilead's unilateral control of supply and price − Criticism of exclusion of PURPOSE-2 countries as unethical − Criticism of diversion clauses |

| People's Medicines Alliance [29] | “This exciting news is marred by Gilead's refusal to work with the UN-backed Medicines Patent Pool to license a generic version of this medicine for developing countries.” − Criticism of exclusion of MICs − Criticism of lack of transparency in definition of “high-incidence resource-limited” countries − Criticism of lack of transparency on price |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LMIC, low- and middle-income countries; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

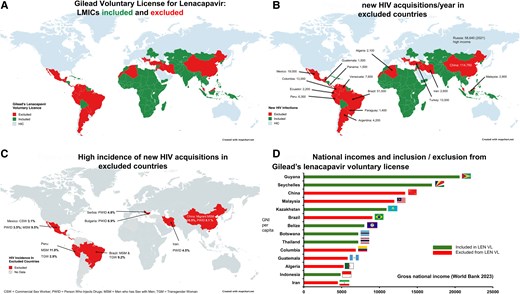

First, the agreement from Gilead excludes key middle-income countries with fast-growing HIV epidemics. The worldwide coverage of the license is shown in Figure 1A. Most of South America has been excluded, along with countries in the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia. As shown in Figure 1B, there were over 200 000 new HIV infections in these excluded countries in 2023; 23% of the global total. These countries also include key populations with HIV incidence higher than in the PURPOSE 1 or 2 trials (Figure 1C).

A, Gilead voluntary license for lenacapavir: LMICs included and excluded. B, new HIV acquisitions/year in excluded countries. C, High incidence of new HIV acquisitions in excluded countries. D, National incomes and inclusion/exclusion from Gilead’s lenacapavir voluntary license. Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LMIC, low- and middle-income countries. Created with mapchart.net.

Second, there is no clear definition of “resource limited” being used to include or exclude countries. As shown in Figure 1D, countries including Colombia and Brazil have been excluded despite having a lower gross national income (GNI) per capita than other countries that were included, such as Guyana and Kazakhstan. No information has been shared on likely prices for excluded countries.

Third, Gilead established this agreement independently from the MPP [14]. Previous voluntary licenses made with the MPP allow greater transparency, surveillance and flexibility [13]. MPP agreements, one of several mechanisms whereby drug originators can provide patented products to markets for expanded access, also allow generic suppliers to export drugs to countries that have ordered compulsory licences. Several MPP licenses also allow supplies outside the licensed territory if there are no patents (for example, generic DTG has so far been supplied to 35 countries outside the licensed territory, two thirds of which are in Latin America and the majority of which are middle-income, through this provision—and a similar clause exists in the MPP licence for CAB-LA for PrEP) [13, 30]. In contrast, Gilead's agreement with six generic suppliers prohibits any exports outside the list of included countries under any circumstances, with strong damages and liability applying if this occurs (including if such supply happens through no fault of the licensee) [14]. This may encourage extreme caution in generic manufacturers' decisions about whom to supply, potentially further restricting access. Though Gilead have made public statements that the lenacapavir licence includes the largest number of countries of any voluntary licence, these diversion clauses limit the number of countries able to legally access generic lenacapavir. As a result, fewer countries are able to access generic lenacapavir compared to, for example, generic cabotegravir [30].

Fourth, people were recruited into the PURPOSE-2 trial in Brazil, Argentina, Mexico and Peru [4]. These countries all have high HIV incidence in key populations, but are excluded from the voluntary license despite a GNI per capita lower than some included countries [14]. The Declaration of Helsinki guidelines, which stipulate ethics obligations for research, require that vulnerable populations in general should only be involved in research if those communities stand to benefit from the results of the research (Section 20). It is not clear whether Gilead will offer lenacapavir at a cost-effective price to these countries. If not, it risks violating Section 20 of the Declaration of Helsinki [16]. Gilead has agreed to supply lenacapavir from their own production until generic versions become available [14]. However, prices have yet to be announced.

Finally, substantial volumes of lenacapavir are not projected to be available until 2027 [31] and until 2028 for widespread generic availability [17]. This will be over 3 years after the PURPOSE trial results were announced. Major generic companies with the potential to accelerate production have been left out of the voluntary licence. If current trends continue, another 4 million people could acquire HIV in the interim. In the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccines and treatments were made available at mass scale in high-income countries within months of study results [32]. Why should similar timelines not be sought for HIV, which has killed over 40 million people worldwide [33], well above the estimated 15 million excess deaths caused by COVID-19 [34]?

Potential Solutions to the Lenacapavir Access Gap

From an access perspective, the simplest solution would be for Gilead to include more countries and generic suppliers in their voluntary license, and to complement these bilateral agreements with a voluntary licence agreement through MPP or one of the other similar mechanisms available to it. These and other changes to the voluntary licence urgently required to promote access to lenacapavir wide enough to eliminate HIV transmission are summarised in Table 3. If these changes are not made, compulsory licenses may be required to widen access.

Changes Needed to Gilead's Lenacapavir Voluntary Licence to Promote Access Wide Enough to Eliminate HIV Transmission Worldwide

| No. . | Issue . | Change Required . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Included countries | Include all LMICs with HIV incidence in key populations above levels in the PURPOSE trials (∼2% per year). |

| 2 | Number of generic suppliers | Include all suppliers who are able to manufacture lenacapavir, supporting scale-up. |

| 3 | Compulsory licences | Enable generic manufacturers to legally supply lenacapavir to countries issuing a compulsory licence. |

| 4 | Access for countries with no patent | Enable generic manufacturers to legally supply lenacapavir to countries issuing a compulsory licence. |

| 5 | Use of lenacapavir as treatment | No licencing restrictions on the use of lenacapavir as treatment. |

| 6 | Co-packaging | No licencing restrictions on the co-packaging of lenacapavir with other drugs. |

| 7 | Research | No restriction on the use of lenacapavir in research as PrEP or treatment. |

| 8 | Confidentiality | No requirement for Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs). |

| 9 | Price transparency | Pricing transparency: all prices publicly available. |

| No. . | Issue . | Change Required . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Included countries | Include all LMICs with HIV incidence in key populations above levels in the PURPOSE trials (∼2% per year). |

| 2 | Number of generic suppliers | Include all suppliers who are able to manufacture lenacapavir, supporting scale-up. |

| 3 | Compulsory licences | Enable generic manufacturers to legally supply lenacapavir to countries issuing a compulsory licence. |

| 4 | Access for countries with no patent | Enable generic manufacturers to legally supply lenacapavir to countries issuing a compulsory licence. |

| 5 | Use of lenacapavir as treatment | No licencing restrictions on the use of lenacapavir as treatment. |

| 6 | Co-packaging | No licencing restrictions on the co-packaging of lenacapavir with other drugs. |

| 7 | Research | No restriction on the use of lenacapavir in research as PrEP or treatment. |

| 8 | Confidentiality | No requirement for Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs). |

| 9 | Price transparency | Pricing transparency: all prices publicly available. |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LMIC, low- and middle-income countries.

Changes Needed to Gilead's Lenacapavir Voluntary Licence to Promote Access Wide Enough to Eliminate HIV Transmission Worldwide

| No. . | Issue . | Change Required . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Included countries | Include all LMICs with HIV incidence in key populations above levels in the PURPOSE trials (∼2% per year). |

| 2 | Number of generic suppliers | Include all suppliers who are able to manufacture lenacapavir, supporting scale-up. |

| 3 | Compulsory licences | Enable generic manufacturers to legally supply lenacapavir to countries issuing a compulsory licence. |

| 4 | Access for countries with no patent | Enable generic manufacturers to legally supply lenacapavir to countries issuing a compulsory licence. |

| 5 | Use of lenacapavir as treatment | No licencing restrictions on the use of lenacapavir as treatment. |

| 6 | Co-packaging | No licencing restrictions on the co-packaging of lenacapavir with other drugs. |

| 7 | Research | No restriction on the use of lenacapavir in research as PrEP or treatment. |

| 8 | Confidentiality | No requirement for Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs). |

| 9 | Price transparency | Pricing transparency: all prices publicly available. |

| No. . | Issue . | Change Required . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Included countries | Include all LMICs with HIV incidence in key populations above levels in the PURPOSE trials (∼2% per year). |

| 2 | Number of generic suppliers | Include all suppliers who are able to manufacture lenacapavir, supporting scale-up. |

| 3 | Compulsory licences | Enable generic manufacturers to legally supply lenacapavir to countries issuing a compulsory licence. |

| 4 | Access for countries with no patent | Enable generic manufacturers to legally supply lenacapavir to countries issuing a compulsory licence. |

| 5 | Use of lenacapavir as treatment | No licencing restrictions on the use of lenacapavir as treatment. |

| 6 | Co-packaging | No licencing restrictions on the co-packaging of lenacapavir with other drugs. |

| 7 | Research | No restriction on the use of lenacapavir in research as PrEP or treatment. |

| 8 | Confidentiality | No requirement for Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs). |

| 9 | Price transparency | Pricing transparency: all prices publicly available. |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LMIC, low- and middle-income countries.

Compulsory licences are issued by countries when drugs are not accessible in their jurisdictions and allow companies to produce or import a drug for local use (predominantly not for export) without permission of the patent holder [35]. There is a strong precedent for compulsory licensing in HIV, guidelines for which have recently been published by the European Union [36, 37]. Both Brazil and Thailand have issued compulsory licences to enable access to Merck's efavirenz [38, 39], and Thailand has issued further compulsory licences for drugs including Abbott's lopinavir/ritonavir when prices were judged to be excessive [39]. More recently, Malaysia issued a compulsory license on another Gilead drug, sofosbuvir, in 2017 [40]. Similarly, Colombia recently issued a compulsory license for the antiretroviral dolutegravir, after ViiV/GSK refused to lower prices. A subsequent legal challenge by ViiV/GSK has attracted substantial criticism [41, 42]. During coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Israel successfully issued a compulsory licence for Kaletra (lopinavir/ritonavir), primarily to ensure adequate supply [36]. Examples of previous successfully issued compulsory licences are summarised in Table 4. Historically, as well as the successful issuing of compulsory licences, the threat of such licences has been a successful mechanism for lowering prices. An early example of this occurred when the US pursued a compulsory licence for ciprofloxacin in 2001, resulting in a discounted price for the drug [43].

Examples of Previous Successful Compulsory Licences Including for HIV and Non-HIV Drugs

| Year . | Country . | Disease . | Drug . | Originator . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | US | Anthrax | Ciprofloxacin | Bayer |

| 2003 | Zimbabwe | HIV | All antiretroviral drugs | All relevant originators |

| 2003 | Malaysia | HIV | Didanosine, zidovudine and lamivudine + zidovidine | ViiV/GSK and BMS |

| 2004 | Mozambique | HIV | Lamivudine, Stavudine and Nevirapine | ViiV/GSK, BMS and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2004 | Zambia | HIV | Lamivudine, Stavudine and Nevirapine | ViiV/GSK, BMS and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2005 | Ghana | HIV | All antiretroviral drugs | All relevant originators |

| 2006 | Thailand | HIV | Efavirenz | Merck |

| 2007 | Thailand | HIV | Lopinavir/ritonavir | Abbott |

| 2007 | Thailand | Coronary heart disease | Clopidogrel | Sanofi-Aventis and BMS |

| 2007 | Rwanda/Canada | HIV | Zidovudine, Lamivudine, and Nevirapine | ViiV/GSK and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2007 | Brazil | HIV | Efavirenz | Merck |

| 2008 | Thailand | Cancer | Erlotinib, letrozole and docetaxel | Roche/Astellas, Novartis and Sanofi |

| 2010 | Ecuador | HIV | Ritonavir | Abbott |

| 2012 | Ecuador | Cancer | Sorafenib | Bayer |

| 2012 | Indonesia | HIV | Nevirapine and lamivudine | ViiV/GSK and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2012 | India | Cancer | Sorafenib | Bayer |

| 2017 | Malaysia | Hepatitis C virus | Sofosbuvir | Gilead |

| 2020 | Israel | COVID-19 | Lopinavir/ritonavir | Abbott |

| 2021 | Ecuador | HIV | Raltegravir | Merck |

| 2024 | Columbia | HIV | Dolutegravir | ViiV/GSK |

| Year . | Country . | Disease . | Drug . | Originator . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | US | Anthrax | Ciprofloxacin | Bayer |

| 2003 | Zimbabwe | HIV | All antiretroviral drugs | All relevant originators |

| 2003 | Malaysia | HIV | Didanosine, zidovudine and lamivudine + zidovidine | ViiV/GSK and BMS |

| 2004 | Mozambique | HIV | Lamivudine, Stavudine and Nevirapine | ViiV/GSK, BMS and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2004 | Zambia | HIV | Lamivudine, Stavudine and Nevirapine | ViiV/GSK, BMS and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2005 | Ghana | HIV | All antiretroviral drugs | All relevant originators |

| 2006 | Thailand | HIV | Efavirenz | Merck |

| 2007 | Thailand | HIV | Lopinavir/ritonavir | Abbott |

| 2007 | Thailand | Coronary heart disease | Clopidogrel | Sanofi-Aventis and BMS |

| 2007 | Rwanda/Canada | HIV | Zidovudine, Lamivudine, and Nevirapine | ViiV/GSK and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2007 | Brazil | HIV | Efavirenz | Merck |

| 2008 | Thailand | Cancer | Erlotinib, letrozole and docetaxel | Roche/Astellas, Novartis and Sanofi |

| 2010 | Ecuador | HIV | Ritonavir | Abbott |

| 2012 | Ecuador | Cancer | Sorafenib | Bayer |

| 2012 | Indonesia | HIV | Nevirapine and lamivudine | ViiV/GSK and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2012 | India | Cancer | Sorafenib | Bayer |

| 2017 | Malaysia | Hepatitis C virus | Sofosbuvir | Gilead |

| 2020 | Israel | COVID-19 | Lopinavir/ritonavir | Abbott |

| 2021 | Ecuador | HIV | Raltegravir | Merck |

| 2024 | Columbia | HIV | Dolutegravir | ViiV/GSK |

Examples of Previous Successful Compulsory Licences Including for HIV and Non-HIV Drugs

| Year . | Country . | Disease . | Drug . | Originator . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | US | Anthrax | Ciprofloxacin | Bayer |

| 2003 | Zimbabwe | HIV | All antiretroviral drugs | All relevant originators |

| 2003 | Malaysia | HIV | Didanosine, zidovudine and lamivudine + zidovidine | ViiV/GSK and BMS |

| 2004 | Mozambique | HIV | Lamivudine, Stavudine and Nevirapine | ViiV/GSK, BMS and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2004 | Zambia | HIV | Lamivudine, Stavudine and Nevirapine | ViiV/GSK, BMS and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2005 | Ghana | HIV | All antiretroviral drugs | All relevant originators |

| 2006 | Thailand | HIV | Efavirenz | Merck |

| 2007 | Thailand | HIV | Lopinavir/ritonavir | Abbott |

| 2007 | Thailand | Coronary heart disease | Clopidogrel | Sanofi-Aventis and BMS |

| 2007 | Rwanda/Canada | HIV | Zidovudine, Lamivudine, and Nevirapine | ViiV/GSK and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2007 | Brazil | HIV | Efavirenz | Merck |

| 2008 | Thailand | Cancer | Erlotinib, letrozole and docetaxel | Roche/Astellas, Novartis and Sanofi |

| 2010 | Ecuador | HIV | Ritonavir | Abbott |

| 2012 | Ecuador | Cancer | Sorafenib | Bayer |

| 2012 | Indonesia | HIV | Nevirapine and lamivudine | ViiV/GSK and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2012 | India | Cancer | Sorafenib | Bayer |

| 2017 | Malaysia | Hepatitis C virus | Sofosbuvir | Gilead |

| 2020 | Israel | COVID-19 | Lopinavir/ritonavir | Abbott |

| 2021 | Ecuador | HIV | Raltegravir | Merck |

| 2024 | Columbia | HIV | Dolutegravir | ViiV/GSK |

| Year . | Country . | Disease . | Drug . | Originator . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | US | Anthrax | Ciprofloxacin | Bayer |

| 2003 | Zimbabwe | HIV | All antiretroviral drugs | All relevant originators |

| 2003 | Malaysia | HIV | Didanosine, zidovudine and lamivudine + zidovidine | ViiV/GSK and BMS |

| 2004 | Mozambique | HIV | Lamivudine, Stavudine and Nevirapine | ViiV/GSK, BMS and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2004 | Zambia | HIV | Lamivudine, Stavudine and Nevirapine | ViiV/GSK, BMS and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2005 | Ghana | HIV | All antiretroviral drugs | All relevant originators |

| 2006 | Thailand | HIV | Efavirenz | Merck |

| 2007 | Thailand | HIV | Lopinavir/ritonavir | Abbott |

| 2007 | Thailand | Coronary heart disease | Clopidogrel | Sanofi-Aventis and BMS |

| 2007 | Rwanda/Canada | HIV | Zidovudine, Lamivudine, and Nevirapine | ViiV/GSK and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2007 | Brazil | HIV | Efavirenz | Merck |

| 2008 | Thailand | Cancer | Erlotinib, letrozole and docetaxel | Roche/Astellas, Novartis and Sanofi |

| 2010 | Ecuador | HIV | Ritonavir | Abbott |

| 2012 | Ecuador | Cancer | Sorafenib | Bayer |

| 2012 | Indonesia | HIV | Nevirapine and lamivudine | ViiV/GSK and Boehringer-Ingelheim |

| 2012 | India | Cancer | Sorafenib | Bayer |

| 2017 | Malaysia | Hepatitis C virus | Sofosbuvir | Gilead |

| 2020 | Israel | COVID-19 | Lopinavir/ritonavir | Abbott |

| 2021 | Ecuador | HIV | Raltegravir | Merck |

| 2024 | Columbia | HIV | Dolutegravir | ViiV/GSK |

Compulsory licensing of key drugs like lenacapavir must be seriously considered if there are no further concessions from Gilead in the near future. However, there are currently deep technocratic and political barriers to the employment of compulsory licences by LMICs [47], where governments cannot act for fear of economic sanctions and/or non-preferential treatment in trade negotiations.

Yet, despite their potential utility and efficiency, compulsory licences and to some extent even voluntary licences are ultimately insufficient responses to a pharmaceutical innovation and distribution system that is structurally inequitable, allowing monopolisation and benefit-hoarding. From HIV to HCV to COVID-19, this system has repeatedly failed to provide access for biomedical advances to LMICs and vulnerable populations. Most basic research for new medicines is carried out in public institutions and funded by taxpayers' money [48], and lenacapavir is no exception [49]. Even when studies are fully funded by pharmaceutical companies, such as the PURPOSE 1 and 2 trials, they are conducted among vulnerable populations that, by ethical regulations, should stand to benefit from the results. To recognise these products as global public goods, policies are needed that enforce equitable access provisions at the point of public-to-private technology transfer [50]. For instance, the “100 Days Mission,” established in response to COVID-19, emphasized the value of voluntary licences and the importance of factors including early licensing (including while the medication is still in development) and sharing of technical expertise between originator and generic companies [51]. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the urgent need to reconsider global trade policies for life-saving interventions, while also increasing capacity for local manufacture. These strategies are being pursued by GAVI, along with new initiatives such as the African Continental Free Trade Area and the African Vaccine Manufacturing Accelerator [52, 53].

Short of such policy advances, smaller steps can be taken to better ensure access for drugs like lenacapavir. For example, in the case of dolutegravir, volume guarantees were negotiated to give generic suppliers confidence to invest in manufacturing capability, ensuring access at a price point below the willingness to pay threshold for most public sector buyers [54]. Now that such a price threshold and the cost of production for lenacapavir has been estimated, transparent and nuanced price negotiation is needed to provide a financial framework that responds specifically to population health needs rather than national income. Similar processes have also been detailed previously for COVID-19 vaccines [55]. The sale price of lenacapavir for HIV prevention will need to take into account the active pharmaceutical ingredient (both the injectable solution and the tablets used for the two-day oral lead-in), injection delivery devices, and health care worker time and clinic infrastructure.

Finally, there may be opportunities for researchers and regulators to better promote post-trial access for novel therapeutics such as lenacapavir, in the broader communities and countries where the research is conducted. These stakeholders can help ensure that international medical research ethics guidelines are upheld. These safeguards set out in the Helsinki Guidelines could be further strengthened. For example, regulatory bodies and registries such as IRB committees, national drug authorities and clinicaltrials.gov could require pharmaceutical companies to describe plans and timelines for post-trial access for interventions that are proven effective prior to study start, for vulnerable communities as well as for trial participants [16, 34].

Although our focus is on PrEP, similar challenges and potential solutions exist for lenacapavir as antiretroviral treatment. Gilead's voluntary licence also allows generic lenacapavir for treatment, but the treatment indication is limited to a very narrow use case of only “heavily treatment-experienced patients”—an extremely small group of people living with HIV. The licence also does not allow manufacture of combinations or even packaging with other antiretrovirals in the same product [14].

Lenacapavir PrEP provides a rare opportunity to revolutionise HIV prevention, transforming the epidemic trajectory in a way that oral PrEP has been insufficient to do. It is vital that the deep inequities in implementation of oral and cabotegravir PrEP are not repeated [56]. A coordinated response from governments, donors, civil society, and the private sector—in particular Gilead—is urgently required to ensure access to lenacapavir is wide enough to eliminate HIV transmission worldwide [56, 57]. If Gilead fails to make key changes to the current licensing structure compulsory licences may need to be employed.

Note

Financial support. This research was funded by a grant from the International Treatment Preparedness Coalition.

References

World Medical Association. Available at: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki/. Accessed 12 December 2024.

UNITAID. Unitaid ready to invest immediately to support accelerated global access to lenacapavir—Unitaid. November 2024. Unitaid. Available at: https://unitaid.org/news-blog/unitaid-ready-to-invest-immediately-to-support-accelerated-global-access-to-lenacapavir/. Accessed 12 December 2024.

Peoples Medicines Alliance. Gilead HIV medicine news marred by little hope for developing countries—People's Medicines. September 2024. Available at: https://peoplesmedicines.org/resources/media-releases/gilead-hiv-medicine-news-marred-by-little-hope-for-developing-countries/. Accessed 12 December 2024.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. COVID excess deaths worldwide. 2024. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/desa/149-million-excess-deaths-associated-covid-19-pandemic-2020-and-2021. Accessed 24 October 2024.

UNAIDS. UNAIDS welcomes new decision in Colombia allowing more affordable access to quality HIV medicines. Available at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2023/october/20231004_colombia. Accessed 24 October 2024.

James Packard Love. Recent examples of the use of compulsory licences on patents. Knowledge Economy International. Available at: https://www.keionline.org/misc-docs/recent_cls.pdf. Accessed 24 March 2025.

Author notes

Potential conflicts of interest. C. F. reports a travel grant for attendance at a Gilead training course. F. V. reports receiving lecture fees and travel support from Roche, grant support, advisory board fees, and provision of drugs from Gilead Sciences, advisory board fees from ViiV Healthcare, lecture fees from Merck and Adcock Ingram, and lecture fees and advisory board fees from Johnson & Johnson. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.