-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

A Kousha, S Farajnia, K Ansarin, M Khalili, M Shariat, L Sahebi, Does the BCG vaccine have different effects on strains of tuberculosis?, Clinical and Experimental Immunology, Volume 203, Issue 2, February 2021, Pages 281–285, https://doi.org/10.1111/cei.13549

Close - Share Icon Share

Summary

Several explanations have been suggested concerning the variety in bacille Calmette–Guerin (BCG) vaccine efficacy on strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). This study aimed to compare the effect of BCG vaccination history in the prevention of the occurrence of Mtb-Beijing and non-Beijing strains. In this cross-sectional study, 64 patients with pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) were recruited from the Iranian border provinces (North West and West). Isolates were subjected to restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, using the insertion sequence IS6110 as a probe (IS6110 RFLP) and drug susceptibility testing using the proportion method. Samples were analyzed with Gel Compare II 6.6 and spss version 18. The mean age [standard deviation (SD)] of the patients was 54·4 (SD = 17·0). Overall, 49 cases (76·56%) had no BCG vaccination scar. The prevalence of Beijing strains was 9·38% and drug resistance proportion among the isolates was 14·1% (nine cases). There was a significant relationship between Beijing strains and tuberculosis (TB)-drug resistance in isolates (χ2 = 26·29, P < 0·001). There was also a strong association between vaccination history and Beijing strains (χ2 = 13·23, P = 0·002). Also, a statistical relationship was observed between Beijing strains and drug-resistant TB among patients with a history of vaccination (χ2 = 7·47, P = 0·002). This association was not maintained in the unvaccinated group (P = 0·102). These findings confirm the claim that the vaccine has different effects on different subspecies of tuberculosis. The cause of the high probability of drug resistance in patients with Beijing-TB and vaccination history requires further investigation with a higher sample size.

Detection of the effectiveness of the BCG vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis in different subspecies and treatment-resistant tuberculosis is critical and could be a major step in improving the vaccine. Our findings approve the claim that the BCG vaccine has different protective effects on Beijing strains of tuberculosis

Introduction

Bacille Calmette–Guerin (BCG) vaccine is still used for tuberculosis (TB) prevention as part of World Health Organization programs (WHO) [1]. According to some studies, vaccination can prevent the occurrence of more severe types in children [2,3]. Also, it strongly protects against extrapulmonary TB [4]. Randomized clinical trial studies have estimated ranging from 0 to 80% [5,6]. Some reasons for these variations are differences in vaccines, the interaction between BCG vaccine and environmental mycobacteria and genetic differences in source populations [4,7–9]. Given that TB is caused by different Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) strains with varying grades of virulence, the WHO has stated that there is a necessity for new, safe and effective vaccines that prevent against all forms of TB, including drug-resistant strains [10].

Beijing strains are the strains associated most often with major TB outbreaks globally [11]. Also, the Mtb Beijing strains were reported to be responsible for widespread resistance to antibiotics commonly used to treat TB [12–14].

Identifying the effectiveness of the vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis in different subspecies, as well as treatment-resistant tuberculosis, is critical and could be a major step in improving the vaccine. In the present study, we intend to compare the effect of BCG vaccination history in the prevention of the occurrence of Mtb-Beijing and non-Beijing strains.

Materials and methods

In this cross-sectional study, 64 patients with sputum-positive pulmonary from North West and West of Iran were investigated (East Azerbaijan n = 30, Kurdistan n = 17 and Kermanshah n = 17 provinces). All the Mtb complexes were identified by culturing on Löwenstein–Jensen (LJ) medium. The samples containing non-tuberculosis mycobacterium were excluded from this study.

Drug susceptibility testing

Drug-susceptibility testing was carried out in LJ medium according to the proportion method recommended by the WHO and the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (IUATLD) using the following materials: isoniazid (INH): 0·2 mg/l, rifampicin (RMP): 40 mg/l, ethambutol (EMB): 2 mg/l and streptomycin (SM): 4 mg/l [15,16].

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from isolates grown on LJ medium as follows; two to three Mtb colony loops were suspended in ×1 Tris-ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (TE) (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) buffer, deactivated at 80°C for 20 min, washed three times with ×1 TE and incubated with lysozyme) Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) at 37°C (for 24 h). Then, proteinase K) Merck (was added and incubated at 65°C (for 24 h).

After adding cetyl trimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)/NaCl (Promega) and NaCl 5 molar to absorb lysed materials and chloroform/isoamyl alcohol in three separate phases, isopropanol) Merck (was added to each sample and maintained in a −20°C freezer for 24 h. Lastly, it was removed from excess materials using 70% ethanol, 10–30 μl distilled water was added and incubated at 37 °C for 3–4 h [17].

IS6110-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP)

The PVUII-digested DNA) Merck) was separated on 1% agarose gels and capillary-blotted onto a nylon membrane. A 245-base pairs internal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) fragment of IS6110 was amplified by PCR and used as a probe. After labeling, the hybridization of the DNA was performed at 42°C (for 24 h) following the manufacturer's instructions (ECL Systems, GE Healthcare UK Limited, Little Chalfont, UK). The total of PVUII-digested DNA of the Mtb reference strain H37RV was used in Southern blot experiments as the control.

Analysis

Fingerprinting patterns of IS6110 were analyzed using Gel Compare II software (Windows 7, version 6.6; Applied Math, Kortrijk, Belgium). Strains greater than 80% similarity to the 19 Beijing reference strains attained from Kremer et al.’s research were considered to be Beijing strains [12]. Autoradiograms were scanned at an optical resolution of 190 dots per inch (dpi); the positions of the IS6110 fragments of the evaluated samples and the reference Beijing strains were then normalized with an internal marker, and their accuracy was verified using the IS6110 banding pattern of the H37RV strain. Dendrograms were designed by hierarchical unweighted pair clustering group method analysis algorithm (UPGMA).

Age, gender (1: male, 2: female), smoking status (1: yes, 2: no) and BCG vaccination information were earned by the subjects’ medical records. Patients’ BCG vaccination area was observed by a physician in the examination for the typical BCG scar in the deltoid part of the upper arm.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 18) software (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Science. The ethics code for this study was 1391/6/18/5/4/5375. Participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study and written consent was obtained from parents of patients aged under 18 years.

Results

In this study, the mean age [standard deviation (SD)] of the patients was 54·4 (17·0). Overall, 30 patients (46·9%) were from East Azerbaijan and 17 cases (26·6%) from Kermanshah and Kurdistan. All patients were HIV-negative [using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)] and were monitored according to the directly observed therapy short-course (DOTS) protocol in treatment. Overall, 49 cases (76·56%) had no BCG vaccination scar and 18 patients (26·9%) had a history of active smoking. Baseline information of the selected Mtb patients is summarized in Table 1.

Baseline information of sputum-positive pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis patients

| Variables . | Co-factor . | . |

|---|---|---|

| Age; mean (SD), year | 54·4 (17·2) | |

| Gender; n (%) | Male | 30 (46·9) |

| Female | 34 (53·1) | |

| The onset of symptoms to treatment; median (IQR), month | 3·0 (5·0) | |

| Provinces; n (%) | East Azerbaijan | 30 (46·88) |

| Kurdistan | 17 (26·56) | |

| Kermanshah | 17 (26·56) | |

| Output of treatment; n (%) | Successful treatment | 45 (70·3) |

| In treatment | 16 (25·0) | |

| expired | 3 (0·047) |

| Variables . | Co-factor . | . |

|---|---|---|

| Age; mean (SD), year | 54·4 (17·2) | |

| Gender; n (%) | Male | 30 (46·9) |

| Female | 34 (53·1) | |

| The onset of symptoms to treatment; median (IQR), month | 3·0 (5·0) | |

| Provinces; n (%) | East Azerbaijan | 30 (46·88) |

| Kurdistan | 17 (26·56) | |

| Kermanshah | 17 (26·56) | |

| Output of treatment; n (%) | Successful treatment | 45 (70·3) |

| In treatment | 16 (25·0) | |

| expired | 3 (0·047) |

SD = standard deviation; IQR = interquartile range.

Baseline information of sputum-positive pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis patients

| Variables . | Co-factor . | . |

|---|---|---|

| Age; mean (SD), year | 54·4 (17·2) | |

| Gender; n (%) | Male | 30 (46·9) |

| Female | 34 (53·1) | |

| The onset of symptoms to treatment; median (IQR), month | 3·0 (5·0) | |

| Provinces; n (%) | East Azerbaijan | 30 (46·88) |

| Kurdistan | 17 (26·56) | |

| Kermanshah | 17 (26·56) | |

| Output of treatment; n (%) | Successful treatment | 45 (70·3) |

| In treatment | 16 (25·0) | |

| expired | 3 (0·047) |

| Variables . | Co-factor . | . |

|---|---|---|

| Age; mean (SD), year | 54·4 (17·2) | |

| Gender; n (%) | Male | 30 (46·9) |

| Female | 34 (53·1) | |

| The onset of symptoms to treatment; median (IQR), month | 3·0 (5·0) | |

| Provinces; n (%) | East Azerbaijan | 30 (46·88) |

| Kurdistan | 17 (26·56) | |

| Kermanshah | 17 (26·56) | |

| Output of treatment; n (%) | Successful treatment | 45 (70·3) |

| In treatment | 16 (25·0) | |

| expired | 3 (0·047) |

SD = standard deviation; IQR = interquartile range.

A total of six (9·5%) isolates were of the Beijing genotype. All six cases were from western provinces, while no Beijing strains were detected in East Azerbaijan. Dendrogram reference Beijing and present study strains are available in our previous study [11].

The mean age (years) of patients in the Beijing and non-Beijing clusters was 65·7 (SD = 16·9) and 56·3 (SD = 21·9), respectively, which were not statistically different (t = 0·72, P > 0·05). Similarly, no significant association was found between gender and strain type (χ2 = 0·67, P > 0·05).

Drug resistance proportion (any resistance to TB drug) among the isolates was 14·1% (nine cases). Specifically, three isolates (4·7%) were resistant to streptomycin (STM), two cases (3·1%) were resistant to rifampicin (RMP) and one (1·5%) was resistant to isoniazid (INH). The proportion of multi-drug-resistant (MDR) TB was 3·12%.

In general, all six Beijing isolates were resistant to at least one TB drug; two of the six Beijing strains exhibited resistance to STM, two strains were MDR (resistance to IHN, RMP and STM or EMB), one strain was resistance to RMP and one other was resistance to INH, STM and EMB (Table 2). We found a statistically significant association between the Beijing strains and TB drug resistance (χ2 = 26.29, P < 0·001).

Patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MtB) drug resistance based on Beijing and non-Beijing Mtb strains

| Mtb drug resistance (n) . | Beijing Mtb; n (%) . | Non-Bejing Mtb; n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| At least one TB drug (9) | 6 (66·7) | 3 (33·7) |

| INH (1) | 0 (0·00) | 1 (100·0) |

| RMP (2) | 1 (50·0) | 1 (50·0) |

| STM (3) | 2 (66·7) | 1 (33·7) |

| INH, STM and EMB (1) | 1 (100·0) | 0 (0·00) |

| MDR*(2) | 2 (100·0) | 0 (0·00) |

| Mtb drug resistance (n) . | Beijing Mtb; n (%) . | Non-Bejing Mtb; n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| At least one TB drug (9) | 6 (66·7) | 3 (33·7) |

| INH (1) | 0 (0·00) | 1 (100·0) |

| RMP (2) | 1 (50·0) | 1 (50·0) |

| STM (3) | 2 (66·7) | 1 (33·7) |

| INH, STM and EMB (1) | 1 (100·0) | 0 (0·00) |

| MDR*(2) | 2 (100·0) | 0 (0·00) |

INH = isoniazid; RMP = rifampicin; EMB = ethambutol; STM = streptomycin; MDR = multi-drug-resistant.

Resistance to IHN, RMP and EMB (one case) and IHN, RMP, and STM (one case).

Patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MtB) drug resistance based on Beijing and non-Beijing Mtb strains

| Mtb drug resistance (n) . | Beijing Mtb; n (%) . | Non-Bejing Mtb; n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| At least one TB drug (9) | 6 (66·7) | 3 (33·7) |

| INH (1) | 0 (0·00) | 1 (100·0) |

| RMP (2) | 1 (50·0) | 1 (50·0) |

| STM (3) | 2 (66·7) | 1 (33·7) |

| INH, STM and EMB (1) | 1 (100·0) | 0 (0·00) |

| MDR*(2) | 2 (100·0) | 0 (0·00) |

| Mtb drug resistance (n) . | Beijing Mtb; n (%) . | Non-Bejing Mtb; n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| At least one TB drug (9) | 6 (66·7) | 3 (33·7) |

| INH (1) | 0 (0·00) | 1 (100·0) |

| RMP (2) | 1 (50·0) | 1 (50·0) |

| STM (3) | 2 (66·7) | 1 (33·7) |

| INH, STM and EMB (1) | 1 (100·0) | 0 (0·00) |

| MDR*(2) | 2 (100·0) | 0 (0·00) |

INH = isoniazid; RMP = rifampicin; EMB = ethambutol; STM = streptomycin; MDR = multi-drug-resistant.

Resistance to IHN, RMP and EMB (one case) and IHN, RMP, and STM (one case).

Overall, 83·3% (five cases) of patients with Beijing's tuberculosis had a history of vaccination, compared with 16·7% (one case) in other patients (χ2= 13·23, P(Fisher's exact test) = 0·002). In the present study, the association between the occurrence of Beijing-Mtb and TB drug resistance in patients was evaluated in terms of vaccination history; thus, in the group with a history of vaccination, 80% (four cases) of patients with Beijing's strain infection had drug resistance compared with no cases in other types of strains. This relationship was statistically significant; χ2 = 10.90, P(Fisher's exact test) = 0·004). In the group that did not have a history of vaccination, 100% (in one case) of patients with Beijing-TB strain had drug resistance, and this percentage was 8·3% in the non-Beijing strains (χ2 = 8·98, P(Fisher's exact test) = 0·102).

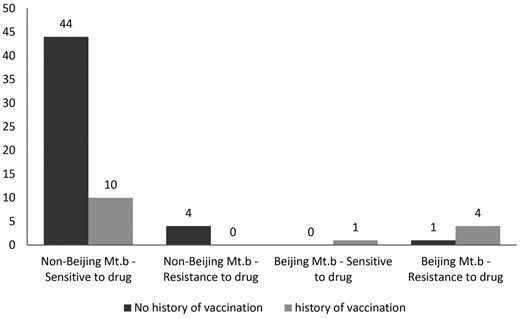

Figure 1 shows the distribution of patients by TB-Beijing strains or TB non-Beijing and drug resistance status according to vaccination history.

Distribution of patients by TB-Beijing strains or non-Beijing and drug resistance status according to vaccination history.

Discussion

Currently, it is assumed that the anti-TB protective property induced by BCG vaccine might be Mtb strain-specific, and this specificity may contribute to the imperfect effectiveness of this vaccine [18,19].

The genealogy of BCG strains displays a series of genomic alterations; including regions of deletion, this region included T cell epitopes that are essential to the human immune system response but had been lost in BCG strains to varying degrees [20]. Some studies have shown that BCG vaccination protects less efficiently against infection by Beijing strains compared with other genotypes [18,21]; conversely, there is a hypothesis that exposure to BCG-induced immunity may select vaccine-escape microorganism variants with a higher capacity for disease breakdown (vaccine-escape specification) [22].

However, Barrón and colleagues, in an animal interventional study, showed that Beijing strain increases virulence after exposure to BCG-induced immunity in vaccinated hosts (interaction between Mtb Beijing-genotype strains and BCG-vaccinated hosts) [23]. In other words, there is concern that Beijing strains may have a tendency for emerging drug resistance and may be spreading worldwide, probably as a result of increased virulence [24–29]. In some parts of the world; for example, in Russia, Estonia and Azerbaijan, a very strong relationship between Beijing families and TB drug resistance was reported [19,24–28]. In some countries where the Beijing strain prevalence is low or absent, the high protective efficacy of the vaccine has been maintained and it seems that these strains have defied almost all measures to conflict TB [18].

In line with previous studies and also in our study, Beijing strains were more common among BCG-vaccinated TB patients in comparison to non-immunized patients [18,21,29]. Despite this, there was a statistically significant relationship between Beijing-Mtb and drug resistance among people who had a history of BCG vaccination. This finding proposed the probability of modification effects between the BCG vaccine and Beijing strains.

Limitations of the study

One of the limitations of this study was that the study design was retrospective, also due to a low budget, so it was not possible to perform fingerprinting on more samples.

Conclusion

These findings confirm the claim that the vaccine has different effects on different subspecies of tuberculosis. The cause of the high probability of drug resistance in patients with Beijing-TB and vaccination history requires further investigation.

Acknowledgements

This study received no funding. The authors thank the staff and patients of Reference Laboratories of Western and Northwestern Iran and Mrs Lesley Carson for editorial clarifications. This research was part of a PhD thesis and reinforced by Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Research Center. This work is a section of the PhD thesis that has been approved by the regional ethics committee (code of 5/4/5375; 8 September 2012) by the ethical standards, as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards in Tabriz University of medical science.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

L. S., K. A. and S. F. proposed the topic; L. S. collected samples; L. S. and M. K. implemented the plan; L. S. analyzed the data; A. K., L. S., S. F. and M. S. drafted the manuscript; A. K. provided comments on successive drafts. All authors read and approved the final draft.

Data availability statement

The data sets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.