-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Camille Bégin, Souvenirs of an awake craniotomy, Brain, Volume 148, Issue 5, May 2025, Pages 1441–1443, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaf124

Close - Share Icon Share

What do you, a bilingual person, do when a surgeon asks which language you wish to keep as he is about to perform an awake craniotomy to remove your right frontal lobe brain tumour?

I decided to keep French. English is for work, rationality, writing. I love how active the language is; how familiar it has become, yet how foreign it remains. I love how it distances me from my experiences, how it gives me space to process them. I love how my intimacy with it has estranged me from ever being able to write in French again. I love how I get to avoid the convoluted sentence structures and tricky grammar of my first language; even though reading the sentences others have sculpted with it remains a voluptuous experience of clauses, commas, pure descriptive stamina that wraps me in words and worlds. French remains my emotional language. The one I cry in, the one I need to communicate with my son, to be silly and caring, to greet him with a ‘Bonjour mon choubidou d’amour’ as he wakes up.

* * *

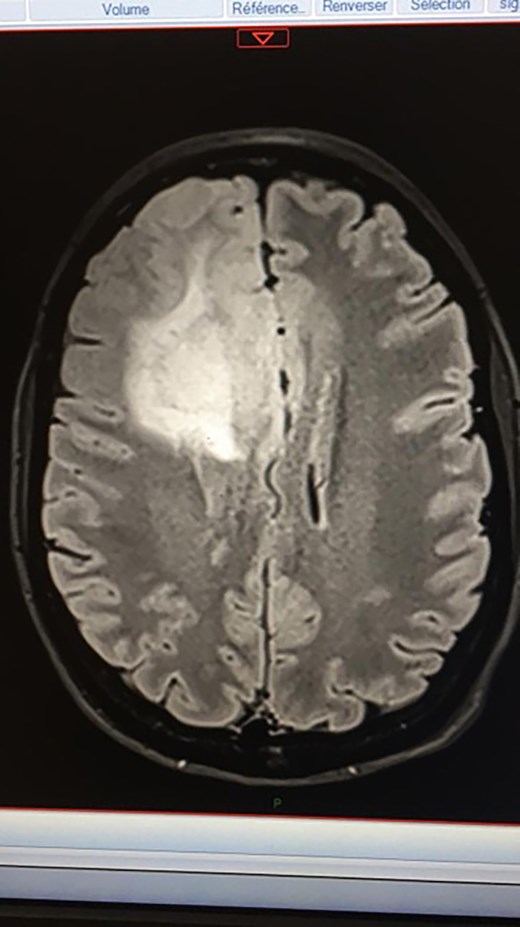

I check into the hospital on 14 April 2020, weeks after my seizure (Fig. 1). It is the earliest they can proceed given the mandatory quarantine after I get repatriated to Toronto from Paris. I am a good candidate for awake surgery—being young and motivated. It will decrease the chances of speech or motor defects afterwards and I want to raise a bilingual kid. The doctors remember what they would have done for a patient like me a few weeks ago, before the pandemic overwhelmed the globe. They are not worn down yet. I am lucky that way.

A photograph of a screen showing the author’s first MRI after her grand mal seizure, Paris, 24 March 2020, 7:42 p.m. Photograph by the author’s husband.

Nick leaves me in the hospital’s lobby, not sure in what state he will get me back. Will I talk? Will I walk? Will I be able to care for myself, let alone our 5-month-old son? Will our new house on top of the hill still fit our needs?

* * *

A psychiatrist I had spoken to on the phone during quarantine comes by my room that first day. He had tried to convince me that, in a world I had lost control over, I could still control my thoughts and feelings:

‘Your emotions are like a balloon, you need to learn how to release them slowly, slowly so that they do not go swirling into the air.’

The image does not form itself in my mind right away, English just doesn’t ‘hit’ my brain the same way. It’s only as I conjure this conversation years later that I see the little girl crying for her red balloon spiralling up in the sky. It’s only when I write it down that I understand this as good advice.

‘Sure,’ is all I had been able to summon myself to respond at the time. I wanted him to stop talking.

This tiny, middle-aged doctor in Vans, khakis, and a light green scrub top is more convincing in person. He gives me space to admit that, yes, being in the hospital for 3 days with no visits for major brain surgery while your breasts are still leaking milk is a nice break from your infant, even if you have bonded very nicely.

I never lose my cool or feel any fear during the stay in hospital. I am past the panic attacks and the tears. I put the swirl on pause to take it all in. When the anaesthetist comes to introduce himself, I am applying face moisturizer.

* * *

Throughout my stay in hospital, I internally recite the names of the nurses and personal support workers who rotate to take care of me (Julietta, Nhung, Claire, Soraya; Julietta, Nhung, Claire, Soraya; Julietta, Nhung, Claire, Soraya). I write it all down after getting home. I want to capture everything, the details, the minutiae, the names. It is instinctive, I do not know I am collecting material for later use. The memories are now mediated by words rather than pure sensations. They form a kaleidoscopic landscape that shifts with each draft. They are ever changing baby blue, light green, soft pink, and beige visions. They are my souvenirs, trinkets from a trippy visit. I write to capture their fading vividness.

* * *

I meet my neurosurgeon for the first time. He is a small, bald, soft-spoken caring man with an Italian last name and tiny glasses. No extra words when he addresses me. He simply sits down to re-explain the procedure he had walked me through on the phone.

‘The anaesthetists will freeze your skull and put you in a light sleep when we do the incision; then we bring you back up and you remain conscious while we remove the tumour.’

‘And that’s when you start testing me?’

‘Yes, we will test you throughout. For physical testing, we will ask you to do things like move your right hand or your left foot, wiggle your toes. For the cognitive testing, we will ask you things like reciting the days of the week or the months of the year backward.’

‘You will test me in both French and English, right?’

‘Yes, as agreed. Dominique, the head nurse, whom you’ve met, is French. She is usually not in the operating room with me, but for your case, she will be. Do you have any questions at this point?’

‘Not that I can think of. But just so you know, I can have a hard time differentiating between my right and left,’ I admit with a bit of shame ‘I wouldn't want this to get in the way of the testing.’

‘Ah, it’s ok. We will put a rubber ducky in the hand we want you to move. It will quack when you do.’

‘Thank you.’

‘What we really want is to have a casual conversation with you, we want you to stay alert and responsive. We will move slowly so that we can remove your tumour as safely as possible and leave you with little impairment. There are no nerve endings in the brain, you won’t feel a thing.’

‘Right.’

‘And then, at the end, the anaesthetic team puts you back to sleep while we close you up. Some people do not remember a thing; others, parts of it; some, all of it.’

That last bit is new information, I knew it would be painless but had not thought about whether I would feel present or not.

‘Sounds good?’

I sign the consent papers.

He leaves but then adds, from the door’s threshold, as he has already taken off his personal protective equipment:

‘One thing I forgot to ask: if it comes to it, which one of your two languages do you want us to spare?’

I stare back.

‘In bilingual people, languages can be located within very specific parts of the brain … no need to answer now, just by tomorrow morning.’

* * *

That’s the kind of question that leaves you speechless, however many languages you might currently command. It brings on a wave of fatigue. I fall into a light sleep while listening to a podcast episode of Le Masque et La Plume, a French broadcast that reviews the latest books, plays, and movies. It has been on air for decades, always at 8 p.m. on Sundays. My surroundings—the swivelling hospital table where my phone is charging, the view of the rooftop air-conditioning system—melt with childhood sensations of drives back from the countryside. The animated critical debates the show is known for would lull me to sleep on the backseat, nestled between the door and one of my brothers, head resting on the cold window, the shadowy back of my parents’ heads in front of me.

I call Nick: ‘You are going to have to improve your French.’ I fall asleep that evening reciting the months of the year backward in both languages.

* * *

After a last MRI, Dominique and a surgical trainee run my wheelchair down a corridor to the operating room. A neurosurgeon, however nice he may be, is not made to wait. The entire team is there. I sit on the operating table while the nurses introduce themselves. I meet one more doctor, a visiting anaesthetist from Chile, Patricia.

I oblige the surgeon and keep the conversation going during the surgery.

‘I went to Chile.’

‘You did?’

‘One of my brothers studied in Santiago for a year. I had a great time.’

‘Where did you go?’

‘All over. We travelled for a month, we went to the Atacama Desert and down close to Antarctica. We spent New Year’s in a great port city, named … mmm, what was the name again? It was close to Santiago, very popular at that time of the year.’

‘Viña del Mar?’

‘No.’

‘Cartagena?’

‘No. I can’t remember.’

‘Dimanche, samedi, vendredi, jeudi, mercredi, mardi, lundi … Sunday, Saturday, Friday, Thursday, Wednesday, Tuesday, Monday.’

It comes back later.

‘Valparaiso!’

The memories of the late, late, night partying with Léopold's friends rush back along with it. It was an alcohol and drug-fuelled one, pisco sours and cocaine. I did not partake in the latter, never been my style. I did make out with a good-looking Chilean who was much more expert at such things than me. The day after, we walked down Valparaiso’s postcard-famous colourful streetscape (Fig. 2), hunting for shade under the southern hemisphere summer sun—me, contented, feeling like a local. We shared a ceviche at the covered market by the beach.

Valparaiso, Chile, 1 January 2009, 9:54 a.m. Photograph by the author.

I stop myself: hold it, they don’t need to know that part.

‘December, November, October, September, August, July, June, May, April, March, February, January … Décembre, novembre, octobre, septembre, août, juillet, juin, mai, avril, mars, février, janvier.’

* * *

Someone keeps feeding me ice chips, so the medical team knows that, if I stop speaking, it is because they ventured into one of my language command centres, not just because of a dry throat. The anaesthetists take turns holding my hand. This is not part of their job description. I asked them to do so at the beginning as I felt a wave of loneliness tinged with panic coming up; the only other time I had been in an operating room before was for my C-section and Nick held my hand as I wept through the procedure—hormones, emotions, or the tumour already growing, we will never know. When Patricia needs both her hands, she gently tugs away. Later, she goes on a lunch break.

I pipe up during a lull in the conversation. They are focused; I worry about being a good patient, keeping the conversation alive.

‘I had a video call with another anaesthetists before the surgery. Why is he not here?’

‘We work as a team, he’s on another case today.’

‘Ah, too bad, he was rather good looking.’

I cannot filter out that quip. I can hear their smiles. Disinhibition they call it.

* * *

Two conversations are taking place, one with the medical team and one with myself. I am surprised that the inner thoughts keep running even though my brain is exposed to fresh air.

I feel like myself: an extrovert who also lives in her head. The small talk comes easy, it always does for me. Apart from rattling off days and months, I do not remember speaking any French during the surgery. How curious, after all the anguish and the decision to remain a francophone whatever may come. I don’t suppose my accent went away. I hear Dominique’s while I chat the team up.

I say something off and Patricia uncovers my eyes.

‘How many fingers can you see?’ Two blue gloved fingers in front of me.

‘Two.’

‘Good.’

‘But what’s that behind your fingers, on the screen?’

She does not answer.

My brain, live and alive. I think: my brain on TV. I watch the end of the show. They give you strong drugs; I do not panic, though I think about whether I should. I see my neurons firing the thought. I remain calm, strapped to the table, fascinated, and wishing this will be the part I remember. I see my brain making the memory of seeing itself. I see my brain create kernels of sentences I will later write. In English. I retain my fluency in French.

Camille Bégin is an award-winning historian of food and the senses who turned to creative writing as she faced a formidable set of lifechanging events. She is currently working on a memoir entitled Crumbs: A Trail of Taste and Illness. Born in France, she has been calling Toronto, Canada, home for half of her life.