-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Andreas Traschütz, Carlo Wilke, Tobias B. Haack, Benjamin Bender, RFC1 Study Group , Matthis Synofzik, Sensory axonal neuropathy in RFC1-disease: tip of the iceberg of broad subclinical multisystemic neurodegeneration, Brain, Volume 145, Issue 3, March 2022, Pages e6–e9, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awac003

Close - Share Icon Share

We read with great interest the article by Currò et al.,1 who screened for RFC1 repeat expansions in patients with chronic idiopathic axonal polyneuropathy. The authors identified bi-allelic RFC1 expansions in 34% of patients with sensory neuropathy, of whom 42% had no additional multisystemic involvement except chronic cough. Building on previous cross-sectional studies,2 Currò et al. propose that sensory neuropathy could be the first affected system in RFC1 disease, which forms the bulk of an iceberg in terms of frequency, with more multisystemic syndromes [such as cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy and vestibular areflexia syndrome (CANVAS)] being less frequent and only later manifestations of an RFC1 spectrum disorder.

We agree that sensory neuropathy might indeed present the main bulk of the iceberg of RFC1-associated phenotypes in terms of ‘frequency' (which, however, still needs to be shown by more unbiased, referral centre-agnostic screening approaches). Here, however, we would like to refine the hypothesis by Currò et al.1 by a complementary concept of RFC1 disease of particular clinical importance: we hypothesize that sensory neuropathy presents only the tip of the iceberg in terms of the broad bulk of actual underlying multisystemic neurodegeneration. Specifically, we here suggest that: (i) even if sensory axonal neuropathy might be clinically predominant in some RFC1 subjects, the underlying neurodegeneration can be much broader and multisystemic in nature; and (ii) this broader underlying neurodegeneration might be present not only in later stages of the disease (i.e. subsequent to the clinically presenting sensory axonal neuropathy), but in fact already at the very same stage of clinically, seemingly isolated, sensory neuropathy. We present evidence for this refined and extended concept of RFC1 disease by two lines of evidence: (i) a novel RFC1 case clinically presenting with sensory axonal neuropathy as the tip of the iceberg of broad concurrent underlying multisystemic involvement; and (ii) a specific analysis of an existing large cohort of 70 RFC1 cases, revealing a cluster of RFC1 subjects in whom sensory axonal neuropathy is just part of a broader concurrent underlying multisystemic involvement, clinically already evident also at the time of first presentation.

Case report, imaging and fluid biomarker findings

A 62-year-old female presented to the general neurology clinic with a 12-months history of sensory neuropathic symptoms of the legs (numbness, tingling and neuropathic pain) with a distal-to-proximal gradient ascending from the toes, accompanied for 6 months by similar glove-shaped sensory symptoms of the hands and by mild afferent gait and balance problems (worse without visual control and on uneven ground). Chronic cough with one to two attacks per day had been present for at least 30 years, and had been given a diagnosis of ‘asthma’. The patient experienced no weakness, dysarthria, dysphagia, movement-induced oscillopsia, urinary or orthostatic symptoms.

Neurological examination confirmed reduced touch sense below the knees and at the fingers, mildly impaired vibration sense at the hip, knee, and malleolar level (all 5/8 on Rydel-Seiffer tuning fork), and mild sensory ataxia with a positive Romberg test and mildly impaired tandem gait and tandem stance [Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA): 1.5 points; generally accepted cut-off for ataxia: SARA ≥3 points3], without muscle weakness, atrophy, or reduced tendon reflexes. Nerve conduction studies confirmed an axonal sensory neuropathy with absent sensory nerve action potentials of the radial, median, sural, and superficial peroneal nerve, while tibial, peroneal, and ulnar motor conduction studies as well as ultrasound of the peripheral nerves were normal. Laboratory investigations (including routine CSF analysis, vitamin B12, folic acid, HbA1c, angiotensin converting enzyme, soluble IL2 receptor, vasculitis screening, antineuronal and ganglioside antibodies, and paraproteins) were unremarkable, except positive monoclonal IgG kappa in immunofixation. Because of the co-occurrence of sensory axonal neuropathy and chronic cough, RFC1-disease was included in the broader differential diagnosis, with targeted genetic testing (flanking PCR, complemented by triple-primer PCR4–6) revealing bi-allelic pathogenic AAGGG expansions (>115 repeats) in RFC1.

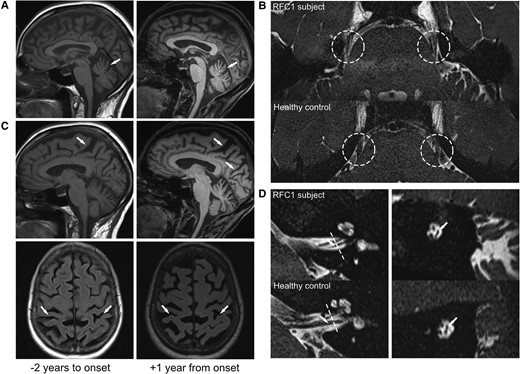

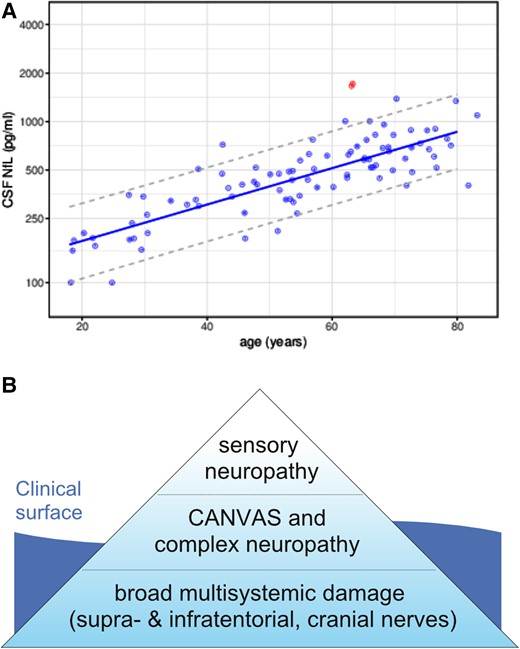

While sensory neuropathy was the clearly predominant clinical presentation, it was only the outward indicator of an in fact broad underlying subclinical multisystemic neurodegeneration, present already at this early stage of the disease course (i.e. 12 months after the onset of sensory symptoms), as evidenced by (i) high-resolution MRI; and (ii) molecular CSF biomarkers. High-resolution MRI (Siemens PrismaFit 3 T, 64 channel head coil, with 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 3D MPRAGE, and 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.4 mm3 3D ZOOMit T2 SPACE) demonstrated atrophy of the parietal cortex, the cerebellum, and also the vestibular and trigeminal nerve (Fig. 1). Both parietal and cerebellar atrophy were subclinically progressive and in fact already visible in retrospect on cerebral MRI images that had been acquired 3 years earlier (i.e. 2 years before onset of clinical symptoms of sensory neuropathy) in an external outpatient centre as part of the routine work-up of a syncope. In line with this broader underlying neuronal damage, CSF levels were substantially increased not only for neurofilament light (NfL) chain [1663 pg/ml, reference value <941 pg/ml, for comparison: spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 1000 pg/ml (pre-symptomatic) to ∼4000 pg/ml (symptomatic),7 for age-related NfL reference values of 89 control subjects, see Fig. 2A, assessed by ELISA, UmanDiagnostics NF-light kit], but also for total tau (595 pg/ml, reference: <404; ELISA, Lumipulse G System). The increased levels of these neuronal damage markers were confirmed in a second independent CSF sample, taken at a second independent time point three months later (NfL: 1720 pg/ml, total tau: 488 pg/ml), thus ruling out any non-disease-related single-time neuronal hit or sampling/measurement error. This stably increased level of CSF neuronal damage markers also indicates a constantly increased neuronal decay occurring in RFC1 disease.

MRI evidence of multisystemic supra- and infratentorial neurodegeneration in RFC1-disease, presenting clinically only with sensory neuropathy. MRI showing cerebellar atrophy (A, sagittal T1) and parietal atrophy (C; sagittal T2 and axial FLAIR) already 2 years before (left column) and 1 year after (right column) the onset of sensory symptoms, with visible progression already in this short time-frame, all still subclinical. High-resolution imaging also revealed severe atrophy of the trigeminal nerve (B, axial T2 SPACE), and vestibular nerve (D, sagittal T2 SPACE). Dashed lines indicate coronal plane demonstrated in the right column of D.

CSF evidence and refined hypothesis of multisystemic neurodegeneration in RFC1-disease. (A) Increased CSF levels of NfL in RFC1-disease. CSF levels of NfL in the RFC1 subject (red dots) were increased compared to 89 healthy controls (including control subjects >80 years of age). The dashed lines represent the 90% prediction interval of the CSF NfL levels in controls, modelled by linear regression of the log-transformed data. To confirm the increased NfL levels, the RFC1 subject had been sampled twice at an interval of 3 months (two red circles). (B) The ‘iceberg’ hypothesis of RFC1-disease in terms of underlying neurodegeneration. Sensory neuropathy is just the tip of the iceberg, with a broader bulk of (possibly subclinical) multisystemic supra-, infratentorial and cranial nerve degeneration.

Specific analysis of a large RFC1 cohort

To explore the hypothesis that sensory neuropathy might be just the ‘tip of the iceberg’ of a much broader multisystemic neurodegeneration even already in early stages of RFC1-disease, we next analyzed a cohort of 70 RFC1 subjects (screened among patients with late-onset ataxia or ataxia with features of CANVAS/cough) specifically for presenting symptoms not attributable to sensory neuropathy. Of 70 subjects, 68 (97%) presented cerebellar signs at clinical presentation.6 A systematic reanalysis of that cluster of patients where a thorough neurological examination was available within 5 years since onset of subjectively relevant disease symptoms (n = 8 of 70 patients) confirmed cerebellar signs (dysarthria, dysdiadochokinesia, saccadic pursuit, gaze-evoked nystagmus, downbeat nystagmus, or dysmetric saccades) in six patients (75%), cerebellar atrophy in four of six patients with MRI (67%), cerebral atrophy in one patient (13%), vestibular impairment in all five patients with head impulse testing (100%), and mild cognitive impairment in one patient already at age 50 years.

In sum, our findings are still well in line with the view that sensory neuropathy is one of the main presenting phenotypic clusters of RFC1-disease,1 and that clinical ataxia can be absent or very mild (as indicated by a SARA score of 1.5 points by our case). However, our novel exemplary RFC1 subject demonstrates that—at least in some RFC1 subjects with clinical sensory neuropathy—the underlying neurodegeneration might in fact already be broad and multisystemic. High-resolution MRI revealed degeneration of supra- and infratentorial regions and, interestingly, even also of cranial nerves. This notion of a broader underlying neurodegeneration of the brain and cranial nerves in RFC1-disease receives further support by a recent report of 22 RFC1 cases providing volumetric evidence of basal ganglia, cerebral white matter and cranial atrophy.8

Broad underlying neuronal damage was furthermore evidenced by increased molecular CSF markers of neuronal damage. We here report for the first time increased levels of NfL in RFC1-disease. This raises the prospects of NfL as a promising disease progression (albeit, of course, not diagnostic) fluid biomarker in RFC1-disease, as already reported in other genetic multisystemic ataxias.7,9 While, in theory, increased CSF NfL levels in RFC1-disease might also result from peripheral nerve damage, this explanation is less likely given that also t-tau was elevated—a finding not even observed in the most rapid and severe peripheral neuropathies (e.g. acute inflammatory neuropathies10). Thus, taken together, these findings from our larger RFC1 cohort provide evidence that multisystemic involvement might be present in RFC1-disease from early on, also already at the stage of sensory neuropathy.

To identify and validate the existence of isolated sensory neuropathy as a sizeable, robust endophenotype of RFC1-disease—along the continuous spectrum of RFC1 phenotypic clusters6—it is necessary: (i) to collect a larger number of patients with this presentation; (ii) to follow them up longitudinally (as the sensory neuropathy might be just a transient disease stage in the more multisystemic progressive evolution of RFC1-disease, as suggested by Cortese et al.2; and (iii) to exclude subclinical multisystemic involvement by high-resolution MRI (including cranial nerves) and abnormal high NfL and tau levels in CSF (as demonstrated here). To avoid possible recruitment, assessment and screening biases, recruitment should run across neuropathy, ataxia, vestibular or even movement disorders clinics. Such potential bias might arise from both general neuropathy clinics (as from Currò et al.1) and ataxia clinics (as reported here).

Our results have two major clinical implications. First, they underline the importance of an in-depth neurological, neuroimaging and fluid biomarker investigation in RFC1-disease to exclude also subclinical multisystemic involvement before classifying patients as ‘idiopathic axonal polyneuropathy’, which could just be the tip of the iceberg (Fig. 2B). Second, they suggest that widespread subclinical neuronal degeneration of multiple brain systems might already be ongoing in RFC1-disease even in patients with seemingly isolated sensory neuropathy. This finding highlights that future molecular treatments of RFC1-disease need to start already at the stage of sensory neuropathy—or ideally even earlier.

Data availability

Data underlying this study are available upon reasonable request.

Funding

This work was supported via the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program grant 779257 ‘Solve-RD’ (M.S). A.T. and C.W. receive funding from the University of Tübingen, medical faculty, for the Clinician Scientist Program Grant (#439-0-0 to A.T., #480-0-0 to C.W.). L.S. and M.S. are members of the European Reference Network for Rare Neurological Diseases—Project ID No 739510.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

Appendix 1

RFC1 study group

Full details are provided in the Supplementary material.

Andreas Traschütz, Jennifer Faber, Heike Jacobi, Solveig Montaut, Andoni Echaniz-Laguna, Sevda Erer, Alexander A. Tarnutzer, Thomas Klockgether, Bart P. van de Warrenburg, Martin Paucar, Dagmar Timmann, Jose Gazulla, Michael Strupp, German Moris, Alessandro Filla, Mathieu Anheim, Jon Infante, A. Nazli Basak, Matthis Synofzik.