-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Keith A Josephs, Ian Mackenzie, Matthew P Frosch, Eileen H Bigio, Manuela Neumann, Tetsuaki Arai, Brittany N Dugger, Bernardino Ghetti, Murray Grossman, Masato Hasegawa, Karl Herrup, Janice Holton, Kurt Jellinger, Tammaryn Lashley, Kirsty E McAleese, Joseph E Parisi, Tamas Revesz, Yuko Saito, Jean Paul Vonsattel, Jennifer L Whitwell, Thomas Wisniewski, William Hu, LATE to the PART-y, Brain, Volume 142, Issue 9, September 2019, Page e47, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz224

Close - Share Icon Share

Sir,

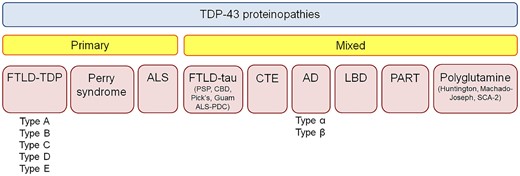

We wish to address the recent proposal of a disease entity newly titled ‘limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE)’ (Nelson et al., 2019) which, to our reading, is itself a derivative of the 2016 proposed term cerebral age-related TDP-43 with sclerosis (CART) (Nelson et al., 2016). The transactive response DNA binding protein of ∼43 kD (TDP-43) was first reported in 2006 to be a main component of ubiquitinated inclusions in autopsy-confirmed cases of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) negative for tau immunoreactivity (Arai et al., 2006; Neumann et al., 2006). Over a decade of research into FTLD-TDP (and FTLD-U before it) has highlighted important phenotypic variability in TDP-43-immunoreactive lesions resulting in the identification of five different types of FTLD-TDP (Mackenzie et al., 2006, 2011; Sampathu et al., 2006; Josephs et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2011, 2017). There have also been important advances in the molecular and biochemical characterization of TDP-immunoreactive in FTLD-TDP (Sampathu et al., 2006; Hasegawa et al., 2008; Igaz et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009; Bigio et al., 2013; Laferriere et al., 2019). Soon after the initial characterization of TDP-immunoreactive lesions in FTLD and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, TDP-immunoreactive lesions were identified in 25–33% of cases with pathologically confirmed Alzheimer’s disease (Amador-Ortiz et al., 2007; Higashi et al., 2007). TDP-immunoreactive lesions related to Alzheimer’s disease were initially thought to appear first in the hippocampus (Amador-Ortiz et al., 2007), but more detailed morphological studies involving multiple anatomical regions revealed the amygdala to be the earliest affected region (Higashi et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2008; Arai et al., 2009) followed by the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus, occipitotemporal cortex, insular and inferior temporal cortex, brainstem, and frontal neocortex and basal ganglia (Josephs et al., 2014, 2016); a scheme that has been independently validated (Tan et al., 2015). TDP-immunoreactive lesions have also been described in cognitively normal individuals (Wilson et al., 2011; Arnold et al., 2013; Uchino et al., 2015; Wennberg et al., 2019) including those with asymptomatic definite primary age related tauopathy (PART) (Josephs et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019), as well being associated with other well-defined clinic-pathological entities (Fig. 1) including Lewy body disease (with or without co-existing Alzheimer’s disease) (Arai et al., 2009; McAleese et al., 2017), the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/parkinsonism-dementia complex of Guam (Hasegawa et al., 2007; Geser et al., 2008), Pick’s disease (Freeman et al., 2008), progressive supranuclear palsy (Yokota et al., 2010; Koga et al., 2017), corticobasal degeneration (Uryu et al., 2008; Koga et al., 2018), polyglutamine diseases such as Huntington’s disease (Schwab et al., 2008), Machado-Joseph disease (Tan et al., 2009) and spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (Toyoshima et al., 2011), Perry syndrome (Wider et al., 2009), and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (McKee et al., 2010).

TDP-43 immunoreactive inclusions can be found in many different neurodegenerative diseases. Currently TDP-43 proteinopathies are divided into primary TDP-43 proteinopathies and mixed (secondary) TDP-43 proteinopathies. AD = Alzheimer’s disease; ALS = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CBD = corticobasal degeneration; CTE = chronic traumatic encephalopathy; FTLD = frontotemporal lobar degeneration; LBD = Lewy body disease; PART = primary age related tauopathy; PDC = Parkinson-dementia complex; PSP = progressive supranuclear palsy; SCA = spinocerebellar ataxia.

The term LATE is proposed as a catchy acronym to describe the presence of TDP-immunoreactive lesions in Alzheimer’s disease, as well as in older adults. The review manuscript describing LATE, of which many of the authors of this response are cited in, provides a thorough appraisal of an important topic and is meritorious in promoting recognition of TDP-43 and encouraging future research, as well as the development of neuroimaging and molecular biomarkers. However, we question the term’s novelty and nosology, the framework that seemingly separates LATE from FTLD-TDP and other diseases, and the proposed guidelines provided for assessing LATE and LATE-NC. As the authors identify, the term LATE is new, although there is an extensive literature on the relationship between TDP-immunoreactive inclusions and clinical and imaging features, both in isolation and in association with Alzheimer’s disease. LATE is used to rebrand already characterized features, yet identifies no new TDP-43 pathological subtype, no link between TDP-immunoreactive pathology with new cognitive symptoms (other than likelihood of dementia diagnosis) according to known brain–behaviour relationship, and no biochemical demonstration that TDP-immunoreactive lesions in older adults with and without Alzheimer’s disease are equivalent to each other or distinct from those in FTLD-TDP and other neurodegenerative diseases. Critically, using the term encephalopathy (‘E’ of LATE) presumes causation of functional impairment in the cerebrum and by incorporating the term encephalopathy, LATE implies a clinicopathological entity, when in reality LATE is only describing the pathology LATE-NC; similar to pathologies such as argyrophilic grains disease (Braak and Braak, 1987), primary age-related tauopathy (Crary et al., 2014), ageing-related tau astrogliopathy (Kovacs et al., 2016) and amygdala Lewy bodies (Uchikado et al., 2006), which are not considered clinicopathological entities. Akin to the dichotomy of language between frontotemporal dementia and FTLD, LATE is something that, by definition, cannot be diagnosed under the microscope (i.e. encephalopathy). And as these lesions can be observed in the absence of cognitive alterations, rendering a diagnosis of an encephalopathy in a cognitively normal individual is an oxymoron (normal cognition with limbic associated TDP-43 encephalopathy).

Proposing that LATE is a distinct clinicopathological entity also overlooks the possibility that TDP-immunoreactive lesions in Alzheimer’s disease could reflect impaired cellular function in end-stage neurodegeneration, and ignores the fact that the statistical association between TDP-immunoreactive pathology and a dementia diagnosis in old age is likely both not independent from Alzheimer’s disease and other pathologies, and, in all likelihood, a reflection of competing relative risks of various degrees as one ages. In addition, the term limbic-predominant is an over simplification of the distribution of pathology. In fact, it has been demonstrated that there are different subtypes of TDP immunoreactivity that have different regional associations, with only one specific subtype of neurofibrillary tangle-associated TDP proving to be truly limbic-predominant (Amador-Ortiz et al., 2007; Josephs et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). The other subtype is associated with TDP-43 involving cortical and subcortical and brainstem regions identical to those affected in FTLD-TDP (Josephs et al., 2019). This is akin to Lewy body disease, which can also have a limbic-predominance, but to label it as such would ignore the brainstem and diffuse distributions of the pathology. Different subtypes of TDP-immunoreactive also have different genetic and pathological associations, including with hippocampal sclerosis; important differences that would be lost when grouping subtypes together (Murray et al., 2014; Josephs et al., 2019).

Third, this paper does not consider how LATE can be distinguished from FTLD-TDP or the fact that LATE depends on a relative selection bias towards Alzheimer’s disease-related diseases while ignoring the fact that TDP-43 has been identified in many other neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 1) making teasing apart coincident versus associated processes a challenge. Of importance is the fact that a proportion of cases of Alzheimer’s disease and ageing have TDP-immunoreactive lesions present in frontotemporal neocortex (Arai et al., 2009; Josephs et al., 2014, 2016; Nag et al., 2018). It has been shown that such cases are strongly associated with single nucleotide polymorphisms in the TMEM106B gene (Josephs et al., 2019), which is similar to the observed associations in FTLD-TDP (Van Deerlin et al., 2010). It is, therefore, unclear whether it is appropriate to make a diagnosis of LATE in the presence of a TDP-43 stage >3 (Josephs et al., 2014, 2016), as opposed to a diagnosis of FTLD-TDP. The description of LATE also does not square with evidence that FTLD-TDP can occur in old age (Jellinger, 2006; Pao et al., 2011), and that age itself may modify the clinical phenomenology of neuropathology due to the brain’s structural and functional reorganization.

The authors provide guidelines on how to assess LATE-NC neuropathologically and suggest analysing a few specific regions of the brain with the intent to have a limited number of TDP-43 stages. While this simplifies neuropathological analysis and is touted as being cost effective, it collapses data-driven staging schemes but without the requisite scientific evidence for doing so. This proposal mirrors the NIA-AA neuropathological guidelines for the pathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, which collapse the Braak (Braak and Braak, 1991), Thal (Thal et al., 2002) and CERAD (Mirra et al., 1991) staging schemes. However, collapsing the TDP-43 staging scheme at such an early point in time when it was only published in the past few years, stifles the fields ability to understand the implications of the distribution of TDP-43 deposition and goes against the drive by many neuropathologists to include more comprehensive and quantitative assessment methods to unravel currently hidden relationships of pathologies.

The branding of clinical trials since the 1990s—especially names such as EPIC or EXCITE—is said to promote reference to such trials (Berkwits, 2000), but can compete with the understanding of the main message (Berlin, 2013; Narod et al., 2016; Witteman et al., 2018). Whether an acronym such is LATE is needed for diagnostic accuracy and communication between neuropathologists, neurologists, and other investigators is not clear. Therefore, we urge researchers to focus on defining the pathological processes and their biochemical differences underlying TDP-immunoreactive lesions in FTLD and non-FTLD disorders, particularly in diverse populations, and defer broad usage of LATE until (and only if) the science is mature.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.