-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Stacy Blythe, Emma Elcombe, Understanding training and support needs of foster carers of infants in out-of-home care, The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 55, Issue 3, April 2025, Pages 1474–1488, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcae207

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Infants constitute a significant proportion of admissions into out-of-home care (OOHC). These vulnerable infants face heightened health and well-being challenges compared to the general population. Addressing their complex needs is crucial to their well-being and requires knowledgeable foster and kinship carers. However, the extent to which these carers receive specialized training and support for infants is largely unknown. This study provides insights into the experiences of foster carers providing care to infants (<12 months) in Australia. A total of 232 foster carers participated in an online survey, reporting on support received and training in eight key areas: infant nutrition, feeding, bathing, sleeping, immunization, development, attachment, and developmental trauma. Analysis found, only 34 per cent of respondents reported that infants in their care received visits from community nurses or midwives, while 75 per cent took infants to see community health nurses. Training rates for basic infant care were low, ranging from 15 per cent to 30 per cent. Respondents without biological children were more likely to receive training. Surprisingly, 41 per cent of respondents did not receive any training. The majority (87 per cent) of respondents emphasized the need for infant specific training. While further research is necessary, these findings highlight the lack for current support for foster carers of infants in OOHC.

Introduction

Infants and young children (<4 years) constitute a significant proportion of admissions into out-of-home care (OOHC) across Western countries including the United States (Boyd 2019), the United Kingdom (Bunting et al. 2018) and Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2024). In the Australian context, infants under 1 year of age face a higher likelihood of being the subject of allegations and substantiations of child abuse and/or neglect, compared to other aged children, necessitating their placement into OOHC (O'Donnell et al. 2023). In the 12 months prior to 30 June 2023, the rate of substantiated infant (<12 months) maltreatment was 14 per 1,000 compared to 8 per 1,000 for older children (1–14 years) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2024). During this time infants (<12 months) made up 2.6 per cent (n = 1,178) of the OOHC population. While most infants in OOHC receive home-based care from vetted and authorized foster and kinship carers, emerging evidence highlights potential gaps in the carers’ skills related to infant care. Notably, a recent study investigating infant feeding in the OOHC context revealed that a quarter of the carers had not received antenatal/postnatal training as they did not have biological children (Blythe et al. 2021, 2022). This begs the question whether foster and kinship carers are adequately prepared and supported to provide basic infant care-giving such as feeding, settling, and bathing.

Most infants who enter OOHC continue to receive care into their childhood. These infants exhibit high developmental vulnerability (Lima et al. 2024). Moreover, research consistently shows that children in OOHC face more significant health and well-being challenges than the general population (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023a). This includes mental health issues (Engler et al. 2022), developmental and learning delays, and issues related to physical health and emotion regulation (Goemans et al. 2016; Turney and Wildeman 2016). These challenges can arise due to circumstances that lead to a child’s need for OOHC (Engler et al. 2022) or as a consequence of their experiences within the care system itself (e.g. placement instability) (Asif, Breen, and Wells 2024), often originating during infancy and early childhood (Ruff, Aguilar, and Clausen 2016). Addressing these complex needs can be challenging (McLean et al. 2019, 2020) and requires dedicated and knowledgeable caregivers.

Infant care-giving, particularly in the early months, can be overwhelming, especially for first time parents (Patrick et al. 2020). Training and guidance are essential to develop the skills related to infant feeding, soothing, bathing and ensuring the infant’s overall well-being. In Australia, and many other Western countries, child and family health services play a crucial role in providing this support at community-based facilities and through nurse home-visiting services. These services connect specialist nurses with families, offering personalized advice, answering questions, and addressing concerns. Whether it’s teaching proper feeding techniques, demonstrating safe sleeping practices, or helping parents to understand developmental milestones, these nurses contribute significantly to parental confidence and infant health. This professional guidance is vital for new parents (Baxter 2022). Whether infants residing in OOHC and their carers receive these support services is unknown.

Study aims

Foster and kinship carers bear a substantial responsibility for the health and well-being of infants in OOHC. However, the extent to which these carers receive specialized training and support for caring for infants—many of whom have heightened health care requirements—remains largely unexplored. Therefore, the aim of this exploratory study was to gain insight into carers needs related to caring for infants in OOHC and to identify the resources available to support carers in this context.

Methods

This study employed an online survey to collect both qualitative and quantitative data from authorized foster and kinship carers within Australia who had received an infant (child under 12 months of age) into their care within the previous five years. Purposeful and convenience sampling was used to reach the target population. This primarily occurred via carer focussed Facebook electronic newsletters where the aim of the study and survey link were shared.

Ethics

Information regarding the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of research, and the inability to withdraw from the study upon survey submission was included at the beginning of the survey. Participants were asked to acknowledge their understanding of this information before proceeding to complete the survey, and this was deemed consent to participate. This study received ethics approval from the Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee (H14455).

The survey was conducted between March and September 2022, targeting foster and kinship carers in Australia. In addition to basic demographic information, its purpose was to gather data on various topics, including carers’ confidence levels, utilization of community and in-home nursing services, training received before or upon the arrival of an infant, and their preferences for further training. Participants were specifically asked about the first infant and most recent infant they provided cared for. In some cases, this was the same infant and/or could coincide with their first experience as a carer.

Analysis

Data were collected using the Qualtrics online survey platform, then downloaded into SPSS 27.0.1.0 for analysis. Descriptive statistics including counts, percentages and means were used to describe the data. Chi-squared analysis were used to assess associations between categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to assess the associations between categorical and ordinal data. An alpha level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests.

Survey responses

A total of 232 valid responses were used in this analysis. These had a median survey duration of twelve minutes (Interquartile range: 8–18 minutes). These came a from a total survey pool of 313 responses from which the following were removed; six duplicate survey launches, forty for responders who were not a foster/kinship carer of an infant within the last five years, and thirty-five for having a survey of a duration under two minutes.

Results

Carer demographics

Most respondents (98 per cent) were female, in a relationship (71 per cent), and living in New South Wales (61 per cent). The majority of carers (66 per cent) were aged between 35 and 54 years, and 73 per cent had a secondary qualification. One third of carers did not have biological children at the time of reporting. Compared with carers who did have biological children, those without were younger (most commonly 35–44 years vs 45–54 years, P < .001), had fewer years of experience providing OOHC (P = .003), were more likely to be single (P = .006), and were more highly educated (P < .001) (Table 1).

| Respondent demographics . | Carer does not have biological child/ren . | Carer has biological child/ren . | Total . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | Std. MW-U^ . | P . | |

| Age | ||||||||

| 25–34 | 15 | 19.7 | 14 | 9.0 | 29 | 12.5 | 5.15 | <0.001 |

| 35–44 | 34 | 44.7 | 38 | 24.4 | 72 | 31.0 | ||

| 45–54 | 24 | 31.6 | 57 | 36.5 | 81 | 34.9 | ||

| 55–64 | 2 | 2.6 | 31 | 19.9 | 33 | 14.2 | ||

| 65–74 | 1 | 1.3 | 16 | 10.3 | 17 | 7.3 | ||

| Highest level of education | ||||||||

| Did not finish high school | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 4.5 | 7 | 3.0 | −3.93 | <0.001 |

| Completed year 10 | 0 | 0.0 | 27 | 17.3 | 27 | 11.6 | ||

| Completed year 12 | 12 | 15.8 | 16 | 10.3 | 28 | 12.1 | ||

| TAFE or trade qualification | 26 | 34.2 | 55 | 35.3 | 81 | 34.9 | ||

| University undergraduate degree | 19 | 25.0 | 40 | 25.6 | 59 | 25.4 | ||

| University postgraduate degree | 19 | 25.0 | 11 | 7.1 | 30 | 12.9 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 30 | 39.5 | 38 | 24.4 | 68 | 29.3 | 5.64& | 0.018 |

| Partnered | 46 | 60.5 | 118 | 75.6 | 164 | 70.7 | ||

| How long have you been a carer? | ||||||||

| Less than 1 year | 5 | 6.6 | 6 | 3.8 | 11 | 4.7 | 2.94 | 0.003 |

| 1–5 years | 33 | 43.4 | 51 | 32.7 | 84 | 36.2 | ||

| 6–10 years | 24 | 31.6 | 42 | 26.9 | 66 | 28.4 | ||

| 11–15 years | 11 | 14.5 | 26 | 16.7 | 37 | 15.9 | ||

| 16–20 years | 2 | 2.6 | 17 | 10.9 | 19 | 8.2 | ||

| 21–25 years | 1 | 1.3 | 5 | 3.2 | 6 | 2.6 | ||

| 23–30 years | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 3.2 | 5 | 2.2 | ||

| 31+ years | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 2.6 | 4 | 1.7 | ||

| Respondent demographics . | Carer does not have biological child/ren . | Carer has biological child/ren . | Total . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | Std. MW-U^ . | P . | |

| Age | ||||||||

| 25–34 | 15 | 19.7 | 14 | 9.0 | 29 | 12.5 | 5.15 | <0.001 |

| 35–44 | 34 | 44.7 | 38 | 24.4 | 72 | 31.0 | ||

| 45–54 | 24 | 31.6 | 57 | 36.5 | 81 | 34.9 | ||

| 55–64 | 2 | 2.6 | 31 | 19.9 | 33 | 14.2 | ||

| 65–74 | 1 | 1.3 | 16 | 10.3 | 17 | 7.3 | ||

| Highest level of education | ||||||||

| Did not finish high school | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 4.5 | 7 | 3.0 | −3.93 | <0.001 |

| Completed year 10 | 0 | 0.0 | 27 | 17.3 | 27 | 11.6 | ||

| Completed year 12 | 12 | 15.8 | 16 | 10.3 | 28 | 12.1 | ||

| TAFE or trade qualification | 26 | 34.2 | 55 | 35.3 | 81 | 34.9 | ||

| University undergraduate degree | 19 | 25.0 | 40 | 25.6 | 59 | 25.4 | ||

| University postgraduate degree | 19 | 25.0 | 11 | 7.1 | 30 | 12.9 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 30 | 39.5 | 38 | 24.4 | 68 | 29.3 | 5.64& | 0.018 |

| Partnered | 46 | 60.5 | 118 | 75.6 | 164 | 70.7 | ||

| How long have you been a carer? | ||||||||

| Less than 1 year | 5 | 6.6 | 6 | 3.8 | 11 | 4.7 | 2.94 | 0.003 |

| 1–5 years | 33 | 43.4 | 51 | 32.7 | 84 | 36.2 | ||

| 6–10 years | 24 | 31.6 | 42 | 26.9 | 66 | 28.4 | ||

| 11–15 years | 11 | 14.5 | 26 | 16.7 | 37 | 15.9 | ||

| 16–20 years | 2 | 2.6 | 17 | 10.9 | 19 | 8.2 | ||

| 21–25 years | 1 | 1.3 | 5 | 3.2 | 6 | 2.6 | ||

| 23–30 years | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 3.2 | 5 | 2.2 | ||

| 31+ years | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 2.6 | 4 | 1.7 | ||

Standardized test statistic from the Mann–Whitney U test.

Pearson’s Chi-squared test statistic.

| Respondent demographics . | Carer does not have biological child/ren . | Carer has biological child/ren . | Total . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | Std. MW-U^ . | P . | |

| Age | ||||||||

| 25–34 | 15 | 19.7 | 14 | 9.0 | 29 | 12.5 | 5.15 | <0.001 |

| 35–44 | 34 | 44.7 | 38 | 24.4 | 72 | 31.0 | ||

| 45–54 | 24 | 31.6 | 57 | 36.5 | 81 | 34.9 | ||

| 55–64 | 2 | 2.6 | 31 | 19.9 | 33 | 14.2 | ||

| 65–74 | 1 | 1.3 | 16 | 10.3 | 17 | 7.3 | ||

| Highest level of education | ||||||||

| Did not finish high school | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 4.5 | 7 | 3.0 | −3.93 | <0.001 |

| Completed year 10 | 0 | 0.0 | 27 | 17.3 | 27 | 11.6 | ||

| Completed year 12 | 12 | 15.8 | 16 | 10.3 | 28 | 12.1 | ||

| TAFE or trade qualification | 26 | 34.2 | 55 | 35.3 | 81 | 34.9 | ||

| University undergraduate degree | 19 | 25.0 | 40 | 25.6 | 59 | 25.4 | ||

| University postgraduate degree | 19 | 25.0 | 11 | 7.1 | 30 | 12.9 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 30 | 39.5 | 38 | 24.4 | 68 | 29.3 | 5.64& | 0.018 |

| Partnered | 46 | 60.5 | 118 | 75.6 | 164 | 70.7 | ||

| How long have you been a carer? | ||||||||

| Less than 1 year | 5 | 6.6 | 6 | 3.8 | 11 | 4.7 | 2.94 | 0.003 |

| 1–5 years | 33 | 43.4 | 51 | 32.7 | 84 | 36.2 | ||

| 6–10 years | 24 | 31.6 | 42 | 26.9 | 66 | 28.4 | ||

| 11–15 years | 11 | 14.5 | 26 | 16.7 | 37 | 15.9 | ||

| 16–20 years | 2 | 2.6 | 17 | 10.9 | 19 | 8.2 | ||

| 21–25 years | 1 | 1.3 | 5 | 3.2 | 6 | 2.6 | ||

| 23–30 years | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 3.2 | 5 | 2.2 | ||

| 31+ years | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 2.6 | 4 | 1.7 | ||

| Respondent demographics . | Carer does not have biological child/ren . | Carer has biological child/ren . | Total . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | n . | % . | n . | % . | Std. MW-U^ . | P . | |

| Age | ||||||||

| 25–34 | 15 | 19.7 | 14 | 9.0 | 29 | 12.5 | 5.15 | <0.001 |

| 35–44 | 34 | 44.7 | 38 | 24.4 | 72 | 31.0 | ||

| 45–54 | 24 | 31.6 | 57 | 36.5 | 81 | 34.9 | ||

| 55–64 | 2 | 2.6 | 31 | 19.9 | 33 | 14.2 | ||

| 65–74 | 1 | 1.3 | 16 | 10.3 | 17 | 7.3 | ||

| Highest level of education | ||||||||

| Did not finish high school | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 4.5 | 7 | 3.0 | −3.93 | <0.001 |

| Completed year 10 | 0 | 0.0 | 27 | 17.3 | 27 | 11.6 | ||

| Completed year 12 | 12 | 15.8 | 16 | 10.3 | 28 | 12.1 | ||

| TAFE or trade qualification | 26 | 34.2 | 55 | 35.3 | 81 | 34.9 | ||

| University undergraduate degree | 19 | 25.0 | 40 | 25.6 | 59 | 25.4 | ||

| University postgraduate degree | 19 | 25.0 | 11 | 7.1 | 30 | 12.9 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 30 | 39.5 | 38 | 24.4 | 68 | 29.3 | 5.64& | 0.018 |

| Partnered | 46 | 60.5 | 118 | 75.6 | 164 | 70.7 | ||

| How long have you been a carer? | ||||||||

| Less than 1 year | 5 | 6.6 | 6 | 3.8 | 11 | 4.7 | 2.94 | 0.003 |

| 1–5 years | 33 | 43.4 | 51 | 32.7 | 84 | 36.2 | ||

| 6–10 years | 24 | 31.6 | 42 | 26.9 | 66 | 28.4 | ||

| 11–15 years | 11 | 14.5 | 26 | 16.7 | 37 | 15.9 | ||

| 16–20 years | 2 | 2.6 | 17 | 10.9 | 19 | 8.2 | ||

| 21–25 years | 1 | 1.3 | 5 | 3.2 | 6 | 2.6 | ||

| 23–30 years | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 3.2 | 5 | 2.2 | ||

| 31+ years | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 2.6 | 4 | 1.7 | ||

Standardized test statistic from the Mann–Whitney U test.

Pearson’s Chi-squared test statistic.

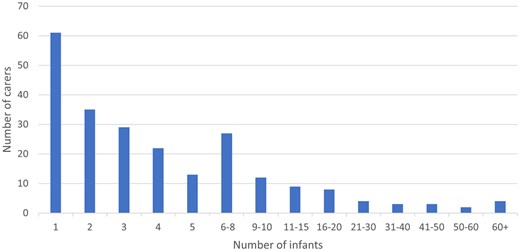

Of the respondents 88 per cent were authorized foster carers, 9 per cent were kinship carers, 10 per cent were adoptive parents and 6 per cent were guardians. The majority of carers had between one and ten years of experience. Respondents were asked how many infants they had cared for during their time as a carer. Approximately one quarter reported caring for one infant, one quarter reported caring for two or three infants and almost half reported caring for four or more infants (Fig. 1).

Infant Placement

Questions were asked about infants’ arrival into care in order to develop an understanding of context.

Age of infant

Around 50 per cent of infants entered care at less than one month of age. Infants under one week of age were the most common group at 31 per cent, followed by infants who were one to four weeks of age (22 per cent). Infants from one to twelve months of age make up the remaining 47 per cent.

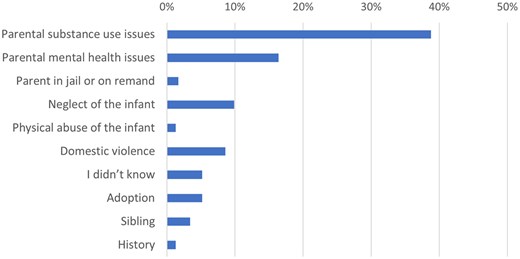

Reason for placement

Respondents were asked their understanding of the reason the infant required OOHC services. The most selected response was ‘parental substance-use issues’ (39 per cent), followed by ‘parental mental health issues’ (16 per cent) (Fig. 2). Those respondents who selected ‘parental substance misuse’ as their understanding of the reason for the infant’s placement into OOHC were also asked if they felt it was possible that the mother was using substances during pregnancy. The majority (99 per cent) of those asked answered ‘yes’ to this question.

Engagement with community health and home-visiting services

Of the 220 respondents who answered the Training and Support questions, 34 per cent percent reported the infant in their care received a visit from a community nurse or midwife. In contrast, 75 per cent of respondents took the infants in their care to see a community health nurse. The number of respondents who received nurse home-visits for the infants in their care and those who took the infants to community health nurses did not differ with respect to respondents having biological children of their own (Table 2).

| Carer has biological child/ren . | Carer does not have biological child/ren . | Chi Sq. . | P-value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | ||||

| Did infant receive a visit from the Community nurse/midwife? | Yes | 48 (32.2%) | 26 (36.6%) | 0.42 | 0.518 |

| No | 101 (67.8%) | 45 (63.4%) | |||

| Did you take Infant for visits with the local Community health nurse? | Yes | 115 (77.2%) | 50 (70.4%) | 1.17 | 0.279 |

| No | 34 (22.8%) | 21 (29.6%) |

| Carer has biological child/ren . | Carer does not have biological child/ren . | Chi Sq. . | P-value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | ||||

| Did infant receive a visit from the Community nurse/midwife? | Yes | 48 (32.2%) | 26 (36.6%) | 0.42 | 0.518 |

| No | 101 (67.8%) | 45 (63.4%) | |||

| Did you take Infant for visits with the local Community health nurse? | Yes | 115 (77.2%) | 50 (70.4%) | 1.17 | 0.279 |

| No | 34 (22.8%) | 21 (29.6%) |

Abbreviations: Chi Sq. test statistic for the Chi-squared test of independence.

| Carer has biological child/ren . | Carer does not have biological child/ren . | Chi Sq. . | P-value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | ||||

| Did infant receive a visit from the Community nurse/midwife? | Yes | 48 (32.2%) | 26 (36.6%) | 0.42 | 0.518 |

| No | 101 (67.8%) | 45 (63.4%) | |||

| Did you take Infant for visits with the local Community health nurse? | Yes | 115 (77.2%) | 50 (70.4%) | 1.17 | 0.279 |

| No | 34 (22.8%) | 21 (29.6%) |

| Carer has biological child/ren . | Carer does not have biological child/ren . | Chi Sq. . | P-value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | ||||

| Did infant receive a visit from the Community nurse/midwife? | Yes | 48 (32.2%) | 26 (36.6%) | 0.42 | 0.518 |

| No | 101 (67.8%) | 45 (63.4%) | |||

| Did you take Infant for visits with the local Community health nurse? | Yes | 115 (77.2%) | 50 (70.4%) | 1.17 | 0.279 |

| No | 34 (22.8%) | 21 (29.6%) |

Abbreviations: Chi Sq. test statistic for the Chi-squared test of independence.

Carer confidence

Respondents were asked about their confidence in providing care for infants. Overall, 87.5 per cent of respondents reported feeling either confident or very confident. Notably, confidence levels were significantly associated with specific factors. Respondents who had biological children of their own demonstrated higher confidence levels (mean score = 4.63) compared to those without biological children (mean score 4.20, Std. MWU = 4.25, P < .001). Additionally, respondents who had prior experience caring for infants exhibited greater confidence (mean score = 4.16) than those without such experience (mean score 4.60, Std. MWU = 4.48, P < .001).

Carer training

The proportion of respondents who reported receiving training on basic infant care (including feeding, nutrition, sleeping and bathing) was notably low with rates ranging from 15 per cent to 30 per cent. Interestingly, respondents without biological children were significantly more likely to receive training in infant nutrition, feeding, bathing, and sleeping (Table 3) compared to respondents with biological children. However, even among this group, training rates remained modest, varying from 28 per cent to 46 per cent. Marginal differences were observed in the likelihood of training related to immunization and typical child development (20 per cent vs 30 per cent), with respondents without biological children slightly more likely to receive training or support.

| At or prior to the arrival of the infant, were you provided with information or training about: . | Carer has biological child/ren . | Carer does not have a biological child/ren . | Chi Sq. . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | ||||

| Infant nutrition | Yes | 29 (19.5%) | 23 (32.4%) | 4.46 | .035* |

| No | 120 (80.5%) | 48 (67.6%) | |||

| Infant feeding | Yes | 33 (22.1%) | 32 (46.4%) | 13.23 | <.001* |

| No | 116 (77.9%) | 37 (53.6%) | |||

| Infant bathing | Yes | 13 (8.7%) | 19 (27.9%) | 13.71 | <.001* |

| No | 136 (91.3%) | 49 (72.1%) | |||

| Infant sleeping | Yes | 19 (12.8%) | 19 (27.9%) | 7.33 | .007* |

| No | 129 (87.2%) | 49 (72.1%) | |||

| Immunization | Yes | 30 (20.4%) | 21 (31.8%) | 3.26 | .071 |

| No | 117 (79.6%) | 45 (68.2%) | |||

| Typical infant development | Yes | 28 (19.0%) | 21 (31.8%) | 4.19 | .041* |

| No | 119 (81%) | 45 (68.2%) | |||

| Infant attachment | Yes | 42 (28.4%) | 23 (34.3%) | 0.77 | .379 |

| No | 106 (71.6%) | 44 (65.7%) | |||

| Developmental trauma | Yes | 52 (35.4%) | 26 (38.8%) | 0.23 | .629 |

| No | 95 (64.6%) | 41 (61.2%) | |||

| At or prior to the arrival of the infant, were you provided with information or training about: . | Carer has biological child/ren . | Carer does not have a biological child/ren . | Chi Sq. . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | ||||

| Infant nutrition | Yes | 29 (19.5%) | 23 (32.4%) | 4.46 | .035* |

| No | 120 (80.5%) | 48 (67.6%) | |||

| Infant feeding | Yes | 33 (22.1%) | 32 (46.4%) | 13.23 | <.001* |

| No | 116 (77.9%) | 37 (53.6%) | |||

| Infant bathing | Yes | 13 (8.7%) | 19 (27.9%) | 13.71 | <.001* |

| No | 136 (91.3%) | 49 (72.1%) | |||

| Infant sleeping | Yes | 19 (12.8%) | 19 (27.9%) | 7.33 | .007* |

| No | 129 (87.2%) | 49 (72.1%) | |||

| Immunization | Yes | 30 (20.4%) | 21 (31.8%) | 3.26 | .071 |

| No | 117 (79.6%) | 45 (68.2%) | |||

| Typical infant development | Yes | 28 (19.0%) | 21 (31.8%) | 4.19 | .041* |

| No | 119 (81%) | 45 (68.2%) | |||

| Infant attachment | Yes | 42 (28.4%) | 23 (34.3%) | 0.77 | .379 |

| No | 106 (71.6%) | 44 (65.7%) | |||

| Developmental trauma | Yes | 52 (35.4%) | 26 (38.8%) | 0.23 | .629 |

| No | 95 (64.6%) | 41 (61.2%) | |||

Statistically significant at alpha < 0.05; abbreviations: Chi Sq. test statistic for the Chi-squared test of independence.

| At or prior to the arrival of the infant, were you provided with information or training about: . | Carer has biological child/ren . | Carer does not have a biological child/ren . | Chi Sq. . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | ||||

| Infant nutrition | Yes | 29 (19.5%) | 23 (32.4%) | 4.46 | .035* |

| No | 120 (80.5%) | 48 (67.6%) | |||

| Infant feeding | Yes | 33 (22.1%) | 32 (46.4%) | 13.23 | <.001* |

| No | 116 (77.9%) | 37 (53.6%) | |||

| Infant bathing | Yes | 13 (8.7%) | 19 (27.9%) | 13.71 | <.001* |

| No | 136 (91.3%) | 49 (72.1%) | |||

| Infant sleeping | Yes | 19 (12.8%) | 19 (27.9%) | 7.33 | .007* |

| No | 129 (87.2%) | 49 (72.1%) | |||

| Immunization | Yes | 30 (20.4%) | 21 (31.8%) | 3.26 | .071 |

| No | 117 (79.6%) | 45 (68.2%) | |||

| Typical infant development | Yes | 28 (19.0%) | 21 (31.8%) | 4.19 | .041* |

| No | 119 (81%) | 45 (68.2%) | |||

| Infant attachment | Yes | 42 (28.4%) | 23 (34.3%) | 0.77 | .379 |

| No | 106 (71.6%) | 44 (65.7%) | |||

| Developmental trauma | Yes | 52 (35.4%) | 26 (38.8%) | 0.23 | .629 |

| No | 95 (64.6%) | 41 (61.2%) | |||

| At or prior to the arrival of the infant, were you provided with information or training about: . | Carer has biological child/ren . | Carer does not have a biological child/ren . | Chi Sq. . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | ||||

| Infant nutrition | Yes | 29 (19.5%) | 23 (32.4%) | 4.46 | .035* |

| No | 120 (80.5%) | 48 (67.6%) | |||

| Infant feeding | Yes | 33 (22.1%) | 32 (46.4%) | 13.23 | <.001* |

| No | 116 (77.9%) | 37 (53.6%) | |||

| Infant bathing | Yes | 13 (8.7%) | 19 (27.9%) | 13.71 | <.001* |

| No | 136 (91.3%) | 49 (72.1%) | |||

| Infant sleeping | Yes | 19 (12.8%) | 19 (27.9%) | 7.33 | .007* |

| No | 129 (87.2%) | 49 (72.1%) | |||

| Immunization | Yes | 30 (20.4%) | 21 (31.8%) | 3.26 | .071 |

| No | 117 (79.6%) | 45 (68.2%) | |||

| Typical infant development | Yes | 28 (19.0%) | 21 (31.8%) | 4.19 | .041* |

| No | 119 (81%) | 45 (68.2%) | |||

| Infant attachment | Yes | 42 (28.4%) | 23 (34.3%) | 0.77 | .379 |

| No | 106 (71.6%) | 44 (65.7%) | |||

| Developmental trauma | Yes | 52 (35.4%) | 26 (38.8%) | 0.23 | .629 |

| No | 95 (64.6%) | 41 (61.2%) | |||

Statistically significant at alpha < 0.05; abbreviations: Chi Sq. test statistic for the Chi-squared test of independence.

Specialized training for infants with higher needs

The proportion of respondents to receive training in infant attachment and developmental trauma were 30 per cent and 35 per cent, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in the rates of training between respondents who did or did not have their own biological children. Additionally, no disparities were observed between respondents who were caring for their first infant and those who had prior experience in infant care.

Total training

Forty-one percent of respondents did not receive training in any of the eight specified areas. Twenty-eight percent received training in one or two areas, while the remaining 31 per cent received training in three or more areas. Notably, the average number of training topics covered was significantly higher for respondents who did not have biological children (mean score 2.6) compared to those who did (mean score 1.7, Std. MW-U = 2.65, P = .008).

Type of training provided

To gain insight into the training provided, respondents who reported receiving training in specific areas were asked about the source of that information or training. They were given two options: (1) being offered the training or (2) finding it themselves. The results revealed that approximately one-third of respondents who reported being trained had independently sought out the information. Interestingly, respondents were more likely to find information related to typical infant development on their own. Conversely, they were more likely to be offered training materials related to developmental trauma (Table 4).

| Found it myself . | Offered to me . | |

|---|---|---|

| Infant nutrition | 18 (35.3%) | 33 (64.7%) |

| Infant feeding | 15 (23.4%) | 49 (76.6%) |

| Infant bathing | 9 (28.1%) | 23 (71.9%) |

| Infant sleeping | 12 (31.6%) | 26 (68.4%) |

| Immunization | 18 (36.7%) | 31 (63.3%) |

| Typical infant development | 25 (51.0%) | 24 (49.0%) |

| Infant attachment | 21 (32.8%) | 43 (67.2%) |

| Developmental trauma | 18 (23.4%) | 59 (76.6%) |

| Found it myself . | Offered to me . | |

|---|---|---|

| Infant nutrition | 18 (35.3%) | 33 (64.7%) |

| Infant feeding | 15 (23.4%) | 49 (76.6%) |

| Infant bathing | 9 (28.1%) | 23 (71.9%) |

| Infant sleeping | 12 (31.6%) | 26 (68.4%) |

| Immunization | 18 (36.7%) | 31 (63.3%) |

| Typical infant development | 25 (51.0%) | 24 (49.0%) |

| Infant attachment | 21 (32.8%) | 43 (67.2%) |

| Developmental trauma | 18 (23.4%) | 59 (76.6%) |

| Found it myself . | Offered to me . | |

|---|---|---|

| Infant nutrition | 18 (35.3%) | 33 (64.7%) |

| Infant feeding | 15 (23.4%) | 49 (76.6%) |

| Infant bathing | 9 (28.1%) | 23 (71.9%) |

| Infant sleeping | 12 (31.6%) | 26 (68.4%) |

| Immunization | 18 (36.7%) | 31 (63.3%) |

| Typical infant development | 25 (51.0%) | 24 (49.0%) |

| Infant attachment | 21 (32.8%) | 43 (67.2%) |

| Developmental trauma | 18 (23.4%) | 59 (76.6%) |

| Found it myself . | Offered to me . | |

|---|---|---|

| Infant nutrition | 18 (35.3%) | 33 (64.7%) |

| Infant feeding | 15 (23.4%) | 49 (76.6%) |

| Infant bathing | 9 (28.1%) | 23 (71.9%) |

| Infant sleeping | 12 (31.6%) | 26 (68.4%) |

| Immunization | 18 (36.7%) | 31 (63.3%) |

| Typical infant development | 25 (51.0%) | 24 (49.0%) |

| Infant attachment | 21 (32.8%) | 43 (67.2%) |

| Developmental trauma | 18 (23.4%) | 59 (76.6%) |

A large number of respondents (n = 206) provided insights into their training preferences and needs. Among these respondents, 87 per cent indicated they should have received specific information or training related to infant care before welcoming an infant into their home. Additionally, 69 per cent expressed that they would have benefited from receiving this type of information (Table 5). Notably, this sentiment was more pronounced among respondents without biological children, 86 per cent of them endorsing the need for pre-placement training, compared to 62 per cent of respondents with biological children (Chi sq = 11.9, P = .001).

| Training question . | Carer has biological child/ren . | Carer does not have a biological child/ren . | Total . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | Chi Sq. . | P-value . | ||

| Do you think foster/kinship carers should be given information or training specific to the care of infants prior to receiving care of an infant? | Yes | 120 (85.5%) | 60 (94%) | 180 (87%) | 3.42 | .065 |

| No | 22 (15.5%) | 4 (6 %) | 26 (13%) | |||

| Do you think you would have benefitted from receiving information or training specific to the care of infants prior to receiving the first infant? | Yes | 88 (62%) | 55 (86%) | 143 (69%) | 11.94 | .001* |

| No | 54 (38%) | 9 (14%) | 63 (31%) | |||

| Do you think infants in foster/kinship care should receive in-home visits from the community nurse/midwife? | Yes | 129 (91%) | 57 (89%) | 186 (90%) | 0.16 | .689 |

| No | 13 (9 %) | 7 (11%) | 20 (10%) | |||

| Do you think infants in foster/kinship care should receive care from local community health nurses? | Yes | 136 (96%) | 62 (97%) | 198 (96%) | 0.14 | .705 |

| No | 6 (4 %) | 2 (3 %) | 8 (4%) | |||

| Training question . | Carer has biological child/ren . | Carer does not have a biological child/ren . | Total . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | Chi Sq. . | P-value . | ||

| Do you think foster/kinship carers should be given information or training specific to the care of infants prior to receiving care of an infant? | Yes | 120 (85.5%) | 60 (94%) | 180 (87%) | 3.42 | .065 |

| No | 22 (15.5%) | 4 (6 %) | 26 (13%) | |||

| Do you think you would have benefitted from receiving information or training specific to the care of infants prior to receiving the first infant? | Yes | 88 (62%) | 55 (86%) | 143 (69%) | 11.94 | .001* |

| No | 54 (38%) | 9 (14%) | 63 (31%) | |||

| Do you think infants in foster/kinship care should receive in-home visits from the community nurse/midwife? | Yes | 129 (91%) | 57 (89%) | 186 (90%) | 0.16 | .689 |

| No | 13 (9 %) | 7 (11%) | 20 (10%) | |||

| Do you think infants in foster/kinship care should receive care from local community health nurses? | Yes | 136 (96%) | 62 (97%) | 198 (96%) | 0.14 | .705 |

| No | 6 (4 %) | 2 (3 %) | 8 (4%) | |||

Statistically significant at alpha < 0.05; Abbreviations: Chi Sq. test statistic for the Chi-squared test of independence.

| Training question . | Carer has biological child/ren . | Carer does not have a biological child/ren . | Total . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | Chi Sq. . | P-value . | ||

| Do you think foster/kinship carers should be given information or training specific to the care of infants prior to receiving care of an infant? | Yes | 120 (85.5%) | 60 (94%) | 180 (87%) | 3.42 | .065 |

| No | 22 (15.5%) | 4 (6 %) | 26 (13%) | |||

| Do you think you would have benefitted from receiving information or training specific to the care of infants prior to receiving the first infant? | Yes | 88 (62%) | 55 (86%) | 143 (69%) | 11.94 | .001* |

| No | 54 (38%) | 9 (14%) | 63 (31%) | |||

| Do you think infants in foster/kinship care should receive in-home visits from the community nurse/midwife? | Yes | 129 (91%) | 57 (89%) | 186 (90%) | 0.16 | .689 |

| No | 13 (9 %) | 7 (11%) | 20 (10%) | |||

| Do you think infants in foster/kinship care should receive care from local community health nurses? | Yes | 136 (96%) | 62 (97%) | 198 (96%) | 0.14 | .705 |

| No | 6 (4 %) | 2 (3 %) | 8 (4%) | |||

| Training question . | Carer has biological child/ren . | Carer does not have a biological child/ren . | Total . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | n (%) . | Chi Sq. . | P-value . | ||

| Do you think foster/kinship carers should be given information or training specific to the care of infants prior to receiving care of an infant? | Yes | 120 (85.5%) | 60 (94%) | 180 (87%) | 3.42 | .065 |

| No | 22 (15.5%) | 4 (6 %) | 26 (13%) | |||

| Do you think you would have benefitted from receiving information or training specific to the care of infants prior to receiving the first infant? | Yes | 88 (62%) | 55 (86%) | 143 (69%) | 11.94 | .001* |

| No | 54 (38%) | 9 (14%) | 63 (31%) | |||

| Do you think infants in foster/kinship care should receive in-home visits from the community nurse/midwife? | Yes | 129 (91%) | 57 (89%) | 186 (90%) | 0.16 | .689 |

| No | 13 (9 %) | 7 (11%) | 20 (10%) | |||

| Do you think infants in foster/kinship care should receive care from local community health nurses? | Yes | 136 (96%) | 62 (97%) | 198 (96%) | 0.14 | .705 |

| No | 6 (4 %) | 2 (3 %) | 8 (4%) | |||

Statistically significant at alpha < 0.05; Abbreviations: Chi Sq. test statistic for the Chi-squared test of independence.

Regarding preferred training methods, 47 per cent of respondents rated ‘face-to-face sessions with a health professional’ as their top choice. For those who did not select this method, an equal proportion expressed preference for either, ‘online’ or ‘in a group setting with other foster/kinship carers’ (13–14 per cent).

Discussion

This study investigated the experiences of carers providing OOHC to infants in Australia. The findings underscore the significant vulnerability of the infants, with carers reporting the majority of infants to be very young and having potentially experienced prenatal exposure to harmful and addictive substances.

This study also reveals that overall, carers lack adequate training and support. Unfortunately, this reported lack of support is a persistent issue leading to significant carer attrition in Australia (Murray, Tarren‐Sweeney, and France 2011; McKeough et al. 2017; Randle et al. 2017; Harding et al. 2018; Luu et al. 2020), and many other countries (e.g. Colton, Roberts, and Williams 2008; Gouveia, Magalhães, and Pinto 2021). In a recent commissioned study, carers in Australia expressed the need for tailored training which addressed the specific individual needs of the carers and the children in their care (Luu et al. 2020). The significant disparities in the training provided for basic infant care found in this study suggests that at times, training may be tailored based on carer needs as carers without biological children were more likely to receive training on essential topics such as infant nutrition, feeding, bathing, settling, and sleeping. However, even with this increased likelihood, only one in three carers received such training.

This study identified the most commonly offered support for carers of infants was information and training related to infant attachment and developmental trauma. This highlights the growing recognition of the pivotal role of primary attachment relationships in healthy infant development. Additionally, acknowledging that infants can experience trauma is crucial. Trauma significantly impacts early child development, affecting attachment, language acquisition, social skills, and emotional regulation (Melville 2017). Infants who undergo trauma may struggle to meet developmental milestones within expected timeframes. However, this study shows that not all carers have access to this critical information, potentially putting the infants in their care at risk of developmental delays. Further, this study did not explore whether the trauma training provided specifically addressed trauma in infants.

A secure attachment relationship with a primary caregiver is essential for healthy infant development (Schore 2017). While this attachment is crucial for all infants, it becomes even more critical for those who have experienced trauma (Breidenstine et al. 2011). However, fostering this attachment can be challenging, especially when infants do not engage, avoid eye contact, fail to give cues, and self-soothe rather than seeking nurturing from their caregivers (Stovall-McClough and Dozier 2004). Carers who understand these dynamics are more likely to proactively engage with infants to promote attachment (West et al. 2020), ultimately resulting in better outcomes.

This study reveals that while some carers receive information and training related to infant attachment, the majority do not. The early days, weeks, and months of an infant’s life represent a critical period for healthy development (NSW Health 2019). To optimize outcomes for infants in OOHC, carers require education on promoting infant health during this crucial time (Dozier, Zeanah, and Bernard 2013).

The lack of information and training on basic infant caregiving is concerning. Particularly troubling are carers without biological children, who may not have attended antenatal classes or received guidance from nurses or midwives. This absence of training can significantly impact carers’ well-being, leading to anxiety and self-doubt and potentially contributing to carer attrition.

An assumption often prevails that carers with biological children possess innate knowledge and experience in infant care. However, survey data challenges this notion, revealing that carers with biological children tend to be older, with an average age range of 45–54 years. In contrast, the average age of birthing mothers in Australia has shifted to 30–34 years (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023b). Consequently, the biological children of carers are likely much older, resulting in a significant gap between their previous infant care-giving experiences. Moreover, guidelines related to infant care continually evolve. For instance, recommendations regarding Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) have undergone multiple revisions over the past two decades (Moon et al. 2022). Carers without young children may inadvertently rely on outdated infant sleeping practices. Additionally, carers who breastfed their own children might lack knowledge about selecting, sterilizing, and bottle-feeding infants to ensure optimal nutrition. These knowledge deficits can inadvertently jeopardize infant well-being and may contribute to carer anxiety and attrition.

The absence of routine basic infant care training within the OOHC system raises questions. Perhaps this gap is perceived as an issue best addressed by the healthcare system. Community health and nurse home visiting programs are designed to support both infants and parents and play a crucial role in early identification, intervention, attachment enhancement, home safety, and parental self-efficacy (Goldfeld et al. 2022). However, while this study found three quarters of carers sought professional support from community health services, only one-third of infants (and their carers) received in-home visits from nurses. This gap likely results from inadequate referral pathways, as mothers are typically referred to home-visiting services during pregnancy or at birth. Unfortunately, no routine alternate referral pathway exists for infants separated from their mothers in the current Australian context.

Carers in this study generally felt confident in meeting infants’ needs. However, survey data revealed that many carers were compelled to seek out information and training on their own as it was not routinely provided. This dissonance indicates that confidence may not be linked to skills, but rather the desire to provide care and the carers ability to actively seek resources and support. Nevertheless, carers in this study emphasized the importance of specific infant training and support. Addressing this need could benefit both carers and the infants they care for.

Strengths and limitations

While this research has limitations, including self-selection bias and overrepresentation of female carers, it sheds light on the experiences of those providing care to infants in OOHC. As the first study of its kind in Australia, it underscores the urgent necessity to better prepare and support carers in this critical role.

Conclusion

This study highlights significant gaps in the training and support provided to foster and kinship carers of infants in OOHC in Australia. Despite the critical role these carers play in addressing the complex needs of vulnerable infants, our findings reveal that a substantial proportion of carers do not receive adequate training in essential areas such as infant nutrition, feed, and developmentally appropriate care. Notably, only 34 per cent of respondents reported that infants in their care received visits from community nurses or midwives and 41 per cent of carers did not receive any infant training at all. These gaps underscore the urgent need for targeted training programs and enhanced support services to ensure that all carers are well-equipped to provide high-quality care. Further research is necessary to explore the long-term impacts of these training deficiencies and to develop strategies for improving the support system for foster and kinship carers.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all the respondents who participated in this research. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funding bodies, Western Sydney University or Adopt Change.

Author contributions

This study was conceptualized by SB. Both authors contributed to the study design. Data analyses were performed by EE, who wrote the first draft of the methods and results sections. SB drafted all other sections. Both authors contributed to several versions and then read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest. None declared.

Funding

This study was co-funded by a partnership grant from the School of Nursing and Midwifery at Western Sydney University and Adopt Change, a not-for-profit advocacy organization that works to ensure all children have access to a safe, nurturing, and permanent family home and that all families are well supported in Australia.