-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sarah Binks, Lyndal Hickey, Airin Heath, Anna Bornemisza, Lauren Goulding, Arno Parolini, Social Workers’ Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Social Work Practice in Schools: A Scoping Review, The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 54, Issue 6, September 2024, Pages 2661–2680, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcae046

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The aim of this scoping review was to establish the breadth of the academic literature regarding the barriers and facilitators to social work practice in schools as perceived by School Social Workers (SSWs). Following the PRISMA-ScR Scoping Review Framework, 42 articles were identified as meeting the inclusion criteria. Five interrelated themes related to the barriers and facilitators to SSW practice were identified: (1) Inadequacy of service delivery infrastructure; (2) SSWs’ role ambiguities and expectations; (3) SSWs’ competency, knowledge and support; (4) School climate and context; and (5) Cultivating relationships and engagement. This scoping review found that social workers perceive far greater barriers than facilitators when delivering services in school settings, with limited evidence related to the facilitators that enhance School Social Work (SSW) practice. Further research regarding the facilitators of SSW practice is needed, specifically in countries where research on this topic is emergent.

Introduction

Within the field of Social Work (SW), School Social Work (SSW) practice is a unique specialization that is committed to supporting students to thrive and reach their full educational potential. There is a growing need for school-based mental health services due to the changing political, economic, cultural and environmental contexts and challenges of the last 10 years, that have seen an increase in xenophobia; racism; and social, economic and health inequalities (Phillippo et al., 2017; Capp et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2021; Daftary, 2022; Villarreal Sosa, 2022). School Social Workers (SSWs) have been instrumental in providing effective psychosocial and mental health interventions to students and their families to overcome such educational barriers and inequities related to homelessness, family violence, bullying, school violence, sexuality, grief and loss, disabilities, school attendance and in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (Reid, 2006; Sawyer et al., 2006; Allen-Meares et al., 2013; Quinn-Lee, 2014; Rueda et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2015; Webber, 2018; Smith-Millman et al., 2019; Johnson and Barsky, 2020; Karikari et al., 2020; Capp et al., 2021; Daftary, 2022). However, for SSWs to effectively respond to the increased need and demands for service, they must successfully overcome barriers to effective SSW practice such as: resource restrictions; unmanageable workloads; ambiguous roles and responsibilities; professional isolation; and limited supervision and training (Agresta, 2006; Teasley et al., 2012; Whittlesey-Jerome, 2012; Phillippo et al., 2017; Beddoe, 2019; Capp et al., 2021).

Failure to address barriers to SSW practice can significantly impact the provision of effective SSW services due to increased job-related stress, job dissatisfaction, compassion fatigue, vicarious trauma, burnout, absenteeism and attrition, which in turn can have a detrimental impact on the provision of effective SSW services addressing mental health and wellbeing needs of students, families and the school system (Lloyd et al., 2002; Agresta, 2006; Caselman and Brandt, 2017). Moreover, the existing research regarding the barriers and facilitators to SSW practice is substantially more deficit focused and provides limited understanding regarding how SSWs respond to these practice challenges, and how they facilitate effective SSW practice. The dearth of evidence regarding SSWs’ perspectives makes it challenging to assess the impact that these barriers may have on SSWs’ wellbeing and may hinder evidence-informed approaches to enhance practitioner wellbeing. Consequently, there is a growing evidence base emphasising that understanding how SSWs perceive the barriers and facilitators to SSW practice is essential to ensuring the continuity of care in the student-SSW relationships, contributing to the improvement of student, family and school outcomes (Caselman and Brandt, 2017).

Despite the available evidence highlighting the importance of understanding the barriers and facilitators of SSW practice and the emergence of National SSW Practice Models in the USA (Frey et al., 2013) and Australia (Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW), 2011), there is a lack of synthesis of the existing literature examining the barriers and facilitators that influence the successful integration of these SSW practice standards in real-world settings and across international perspectives.

The present study addresses this significant shortcoming by synthesising the existing research to identify themes related to the barriers and facilitators to SSW practice that will allow us to understand how SSWs resolve these practice-based challenges, to enhance evidence-informed best practice for SSWs, better inform SW’s education and preparation to enter the field and strengthen the linkages between research and SW practice. Using a scoping review methodology, this study aims to answer the following research question: What evidence exists in the academic literature regarding the perceived barriers and facilitators to SW practice experienced by social workers (SWs) in schools in Australia, Canada, Aotearoa NZ, the UK and USA?

Methods

This review follows the Tricco et al. (2018), the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) framework methodology. A scoping review was chosen as the appropriate method to synthesise the existing research regarding the barriers and facilitators to SSW practice to map the relevant literature and identify key concepts and knowledge gaps (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Levac et al., 2010; Munn et al., 2018). This study uses the population, concept and context (PCC) approach outlined by Peters et al. (2015).

Population

The study focused on Social Workers working in school settings. For this scoping review, a Social Worker is defined as a graduate of a SW education program at the bachelor’s or master’s degree level or is eligible for accreditation with the SW governing body in their location of practice.

Concept

SSWs are trained mental health professionals who provide SW services in a school setting, with the primary goal of supporting a student’s learning potential and facilitates successful learning outcomes and full participation for students, in consultation with school staff, parents and communities (AASW, 2011; National Association of Social Workers (NASW), 2012; Frey et al. 2013; Constable, 2016). While there are a variety of SSW models used internationally, SSW practice broadly encompasses: (1) Evidence-based educationally relevant behaviour and mental health services with students, families and school personnel; (2) Promoting school climate, culture and system change to foster academic achievement; (3) Facilitating access and coordination with school and community resources; and (4) Research, education and professional development (AASW, 2011; NASW, 2012; Frey et al., 2013). For this study, we defined barriers as impediments to the implementation of SSW practice and facilitators as enablers that enhance SSW practice interventions and efficacy (Teasley et al., 2010; IGI Global, 2023).

Context

This study focused on SW practice in primary and secondary schools, which comprise of students in Grades: Kindergarten/Prep to 12. The study included all schools that fit this category, regardless of funding or religious affiliation. To ensure that the identified evidence is comparable and manageable in scope, the inclusion criteria were restricted to published studies of SSWs’ perspectives in Australia, Canada, Aotearoa NZ, the UK and USA. These countries were selected given the similarities in linguistics, governance structures, school systems, colonial histories and the historical development of the social work profession in response to industrialization, urbanization and social inequalities; while at the same time providing a meaningful comparative analysis that recognises the diversity of cultural, historical, political and socioeconomic factors. Given the contextual differences across the five countries, such as the existence or absence of SSW practice models, the variety of SSW roles and responsibilities, the availability of SSW-specific tertiary education, licencing, accreditation and professional representation and specific legislation and funding guiding SSW practice (e.g. No Child Left Behind Act (2002) and Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (2004) in the USA), this study has, where relevant, specified the context specific barriers and facilitators in the results section (Slovak et al., 2006; NASW, 2012).

Eligibility criteria

This study focused on academic, peer-reviewed literature, written in English, between the years January 2000 to February 2022. We limited the search to post-2000 given societal and mental health service system changes that have increased focus on students’ social and emotional wellbeing to reflect the contemporary educational landscape. For full inclusion and exclusion criteria for this scoping review see Table 1.

| Inclusion criteria . | Exclusion criteria . |

|---|---|

|

|

| Inclusion criteria . | Exclusion criteria . |

|---|---|

|

|

| Inclusion criteria . | Exclusion criteria . |

|---|---|

|

|

| Inclusion criteria . | Exclusion criteria . |

|---|---|

|

|

Search strategy

The search strategy and databases were selected in consultation with an expert librarian and authors (SB, AP and LH). In February 2022, the lead author searched seven academic databases: PsycInfo (OVID), CINAHL (EBSCO), ERIC (EBSCO), Medline (OVID), INFORMIT (‘A+ education’ and ‘humanities and social sciences’), ASSIA (ProQuest) and SocINDEX (EBSCO). These databases were chosen given their broad coverage of the SW and social care parameters and fields with the ability to focus results on those most relevant.

Title and abstract were searched in all databases. The following search terms were intentionally broad to capture the relevant literature given the multiple possible terms representing the perspectives of SSWs: ‘Social Work*’ AND (School* OR Education*) AND (Perception* or perceive* or attitude* or perspective* or view* or belie* or opinion* or impression* or experience* or encounter* or identif*). Where available, the search was expanded to subject headings. We included peer reviewed and research chapters in edited books to ensure we captured the depth and breadth of empirical evidence that matched the inclusion criteria. We did not include search terms related to ‘barrier’ or ‘facilitator’ to practice, given we found that this limit introduced bias into the search and excluded some results that would otherwise have been included.

Selection of sources of evidence

All articles were screened by two independent reviewers to minimise potential reviewer bias. The lead author (SB) reviewed all 14,317 articles for title and abstract screening; and 285 for full-text review, while other authors (LH, AH, AB, LK) were second reviewers during both screening stages. During the title and abstract phase, a third reviewer (AP) resolved any conflicts. After the full-text review, a third reviewer (AP) resolved conflicts related to exclusion reasons (e.g. wrong concept or setting), any remaining conflicts were resolved by consensus.

Data charting process

The authors developed a data charting form specifying which variables to extract. Authors (SB, LH and AP) independently charted the data, discussed the results and updated the data charting form in an iterative process. Disagreements on data charting were resolved by consensus and discussion with other authors, if required. Results were reviewed by all authors. The research aim and question guided the data synthesis process, with relevant data being charted into the following categories: the study characteristics (e.g. authors, title, publication year, country, aims/purpose, population, sample size, methodology/methods, relevant outcomes/findings, relevant findings and recommendations (by study authors)). Data regarding the barriers and facilitators to SSW practice was charted based on whether or not the SSWs perceived it to be a barrier or facilitator to SSW practice. Key findings data was synthesised into common themes, guided by the research question, with a focus on the barriers and facilitators to SSW practice (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). Initially, the data were coded under broad themes of ‘barriers’ or ‘facilitators’ and were subsequently grouped into the themes following the conventional content analysis deductive approach, where all data were sorted into categories based on how the different codes were related and linked, and then, organised into meaningful clusters (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). See Supplementary Table S1 for an overview of data synthesised.

Results

Study selection

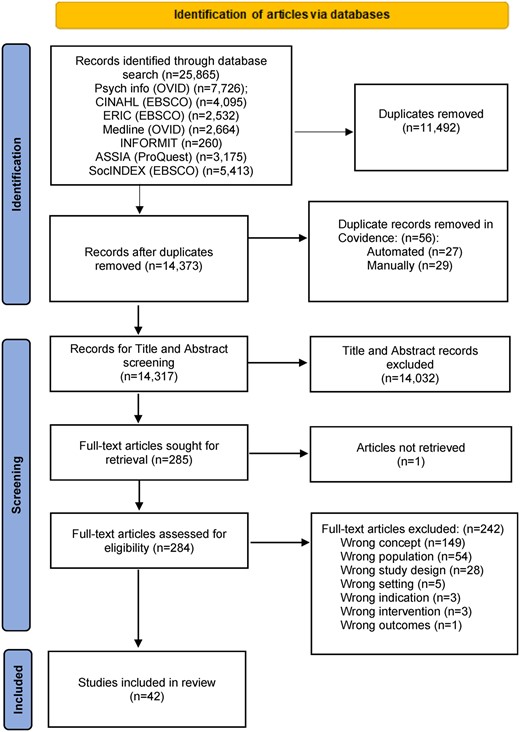

The final search results (n = 25,865) from seven academic databases were exported into ENDNOTE (version X9) bibliographic software (Clarivate Analytics, 2018) and duplicates (n = 11,492) were removed (Figure 1). Screening of articles (n = 14,373) was conducted using COVIDENCE software (Veritas Health Innovation, 2022). Following the title and abstract screening, 14,032 articles were excluded. 285 full-text articles were retrieved and screened, with 242 excluded. One full-text article could not be retrieved. Overall, 42 articles met the inclusion criteria.

Context

Majority (n = 36) of studies were from the USA, with the remaining six studies divided between Australia (n = 2), New Zealand (n = 2), Canada (n = 1) and the UK (England and Wales) (n = 1). There appears an increasing research interest in this area, with over 75% of studies published after 2010 (n = 32); almost half were published after 2015 (n = 19); and 23.8% published since 2020 (n = 10).

Characteristics of sources of evidence

For the included studies, a range of methodologies were employed: qualitative (n = 16), quantitative (n = 10) and mixed methods (n = 16). Methods including interviews, focus groups, questionnaires and document archival records analysis. Ten studies did not disaggregate, or only partially aggregated their data, preventing delineation of SSWs responses from other professionals (Crepeau-Hobson et al., 2005; Reid, 2006; Sawyer et al., 2006; Peabody, 2014; Avant and Lindsey, 2016; Smith-Millman et al., 2019; Sweifach, 2019; Johnson and Barsky, 2020; Heberle et al., 2021; Goodcase et al., 2022). Smith-Millman et al. (2019) noted SSWs perceived ‘barriers’ without defining further.

Synthesis of results: SSW practice barrier and facilitator themes

The analysis of available evidence identified five interrelated themes: (1) Inadequacy of service delivery infrastructure; (2) SSW role ambiguities and expectations; (3) SSWs’ competency, knowledge and support; (4) School climate and context and (5) Cultivating relationships and engagement.

Inadequacy of service delivery infrastructure

SSWs reported that an adequate service delivery infrastructure, such as the availability of human and material resources, were essential requirements to meet student needs, and that a lack of such resources hampered their ability to do their job and increased their stress levels and job dissatisfaction (Agresta, 2006). Of the 42 included papers, 81% (n = 34) identified SSW practice barriers and facilitators related to an inadequacy of service delivery infrastructure. Out of these, 67% (n = 28) reported on barriers only, no articles reported on facilitators only, and 14% (n = 6) identified both barriers and facilitators to SSW practice. SSWs perceived restrictive funding requirements (e.g. limited school resources, scarcity of funding for SSW positions and SSW salaries) as a barrier to SSW service delivery, and some SSWs expressed concerns for the future of SSW practice and job security, particularly during economic hardship (Crepeau-Hobson et al., 2005; Raines, 2006; Teasley et al., 2010, 2012; Bronstein et al., 2011; Lee, 2012; Whittlesey-Jerome, 2012; Peckover et al., 2013; Peabody, 2014; Rueda et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2015; Avant and Swerdlik, 2016; Johnson and Barsky, 2020; Capp et al., 2021; Drew and Gonzalez, 2021; Heberle et al., 2021). SSWs reported that insufficient SSW staff levels impacted their ability to meet student needs, and resulted in unmanageable caseloads, unrealistic SSWs to student ratios, serving multiple schools and the inability to provide services in some areas (Crepeau-Hobson et al., 2005; Raines, 2006; Teasley et al., 2010, 2012; Bronstein et al., 2011; Lee, 2012; Whittlesey-Jerome, 2012; Peckover et al., 2013; Peabody, 2014; Rueda et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2015; Avant and Swerdlik, 2016; Johnson and Barsky, 2020; Capp et al., 2021; Drew and Gonzalez, 2021; Heberle et al., 2021).

Time and logistics were consistently mentioned as resource barriers to SSW practice when inadequate, but were seen as facilitators when SSWs were able to access appropriate and confidential work and meeting space, and were able to be informally present and visible in schools and in the community (Blair, 2002; Crepeau-Hobson et al., 2005; Teasley, 2005; Agresta, 2006; Mann, 2008; Chanmugam, 2009; Teasley et al., 2010 Lee, 2012; Peckover et al., 2013; Avant, 2014; Peabody, 2014; Quinn-Lee, 2014; Rueda et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2015; Avant and Lindsey, 2016; Avant and Swerdlik, 2016; Beddoe, 2019; Johnson and Barsky, 2020;Drew and Gonzalez, 2021; Elswick and Cuellar, 2021; Kelly et al., 2021; Goodcase et al., 2022).

The research evidence identified SSWs reported a lack of material resources, (e.g. specialised curricula or evidence-based practice (EBP) resources) to guide SSW practice; and that documentation and reporting requirements were barriers to SSW practice (Agresta, 2006; Bates, 2006; Reid, 2006; Sawyer et al., 2006; Chanmugam, 2009; Garrett, 2012; Lee, 2012; Quinn-Lee, 2014; Avant and Lindsey, 2016; Phillippo et al., 2017; Elswick and Cuellar, 2021; Heberle et al., 2021). During the COVID-19 school shutdowns, SSWs reported barriers regarding insufficient access to internet, technology and school-based resources and associated software skills, knowledge and support (Capp et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2021; Daftary, 2022). Only in three studies did SSWs identify resources that facilitated SSW practice, such as: electronic records system for data tracking; sharing information and resources; and during the COVID-19 school shutdowns, availability and access to tele-health curricula and activities (Johnson and Barsky, 2020; Capp et al., 2021; Daftary, 2022).

SSW role ambiguities and expectations

SSWs reported numerous challenges regarding the roles, responsibilities and expectations of the social worker role within the school setting. In thirty-five studies (83%), SSWs reported barriers and facilitators to SSW practice regarding SSW role ambiguities and expectations. Out of these, 45% (n = 19) listed barriers only, <1% (n = 4) reported facilitators only and 29% (n = 10) covered both. SSWs reported barriers resulting from insufficient understanding of the SSW role; role ambiguities and conflicts; and an absence of respect or recognition for SSW perspectives and scope of practice (Blair, 2002; Teasley, 2005; Raines, 2006; Reid, 2006; Teasley et al., 2010; Bronstein et al., 2011; Lee, 2012; Whittlesey-Jerome, 2012; Peckover et al., 2013; Avant, 2014; Rueda et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2015; Avant and Swerdlik, 2016; Phillippo et al., 2017; Webber, 2018; Beddoe, 2019; Gherardi and Whittlesey-Jerome, 2019; Karikari et al., 2020; Capp et al., 2021; Drew and Gonzalez, 2021; Elswick and Cuellar, 2021; Heberle et al., 2021). SSWs identified roles dominated by reactionary working conditions; and crisis driven-work, that was overwhelmed by competing demands, expectations and interruptions (Blair, 2002; Sawyer et al., 2006; Chanmugam, 2009; Lee, 2012; Avant, 2014; Peabody, 2014; Miller et al., 2015; Avant and Swerdlik, 2016; Phillippo et al., 2017; Beddoe, 2019; Gherardi and Whittlesey-Jerome, 2019; Elswick and Cuellar, 2021; Heberle et al., 2021; Goodcase et al., 2022). SSWs reported insufficient professional autonomy and professional identity as barriers to practice and some SSWs identified challenges with maintaining boundaries during times of crises response and when providing services remotely during the pandemic (Blair, 2002; Chanmugam, 2009; Lee, 2012; Peckover et al., 2013; Webber, 2018; Capp et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2021; Goodcase et al., 2022). The environments that facilitated SSW practice consisted of low professional role discrepancy, appreciation of the SSW role and expertise, high professional autonomy, support for clinical interventions and special programs and empowered SSWs to balance the complexity of the role with making meaningful contributions (Agresta, 2006; Teasley et al., 2010, 2012; Lee, 2012; Peckover et al., 2013; Peabody, 2014; Johnson and Barsky, 2020; Heberle et al., 2021).

There was evidence that SSWs perceived tensions regarding EBP outcome measure reporting and EBP adaptation to school context; and SSWs noted the dearth of research and failure by SSWs to report practice outcomes negatively impacted cases and justification for the SSW role (Bates, 2006; Raines, 2006; Phillippo et al., 2017). Some SSWs identified successfully adapting EBP and utilizing data tracking to: improve measurement strategies and guide implementation decisions, which increased their ability to meet students’ needs, provide school-wide capacity and support, demonstrate program effectiveness, professional credibility and justified SSW funding (Bates, 2006; Avant, 2014; Avant and Lindsey, 2016; Avant and Swerdlik, 2016; Webber, 2018; Elswick and Cuellar, 2021; Heberle et al., 2021).

SSWs’ competency, knowledge and support

SSWs perceived barriers and facilitators regarding the competencies, knowledge, training and support that they require to effectively responding to the needs of students, families and the school community, while maintaining their own mental health and wellbeing (Teasley et al., 2010; Bronstein et al., 2011). Twenty-eight studies (67%) examined SSWs’ competency, knowledge and support as barriers and facilitators to SSW practice. Of these, only 36% (n = 15) reported barriers only, 14% (n = 6) facilitators only and 17% (n = 7) both. SSWs felt their SW skills, attitudes and compassion were facilitators to SSW practice (Teasley et al., 2010, 2012). Some SSWs identified that inadequate preparation, training or required skills and knowledge from their generalist SW education, specifically lacking school-specific practice knowledge, an understanding of relevant legislation, special education policies and practices, interdisciplinary teams and EBPs specific to SSW practice (Bates, 2006; Reid, 2006; Sawyer et al., 2006; Bronstein et al., 2011; Lee, 2012; Phillippo et al., 2017; Beddoe, 2019; Elswick and Cuellar, 2021). SSWs who completed a school-based field placement, who had professors with practice experience, who felt knowledgeable about diversity issues and felt culturally competent, felt better prepared (Teasley et al., 2010, 2012; Phillippo et al., 2017; Beddoe, 2019). During COVID-19 school shutdowns, some SSWs were overwhelmed by student/family difficulties, felt unprepared and unsupported to deliver online services, unbalanced home/work boundaries and felt remote SSW services as a modality was ineffective or unfair (Capp et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2021; Daftary, 2022).

There was evidence that SSWs perceived barriers resulted from insufficient professional development, training opportunities, support and guidance, which impacted SSW services (Agresta, 2006; Teasley et al., 2010; Lee, 2012; Peckover et al., 2013; Avant, 2014; Peabody, 2014; Avant and Lindsey, 2016; Avant and Swerdlik, 2016; Phillippo et al., 2017; Elswick and Cuellar, 2021; Kelly et al., 2021). SSWs reported increased competence, knowledge and awareness when supported to attend or provided with training and professional development (Teasley, 2005; Teasley et al., 2008, 2010, 2012; Lee, 2012; Peckover et al., 2013; Peabody, 2014).

SSWs repeatedly mentioned the scarcity of professional support and/or clinical or SW supervision as barriers to SSW practice (Teasley et al., 2010; Lee, 2012; Peckover et al., 2013; Peabody, 2014; Quinn-Lee, 2014; Rueda et al., 2014; Phillippo et al., 2017; Webber, 2018; Sweifach, 2019; Capp et al., 2021). SSWs reported consultation and support from SW supervisors and peers facilitated SSW practice; and SSWs also valued constructive consultation and relational support with non-SW administrators on non-counselling topics (Chanmugam, 2009; Peabody, 2014; Phillippo et al., 2017; Sweifach, 2019; Heberle et al., 2021). Some SSWs noted that SSW association membership and SW licensure were facilitators to SSW practice (Raines, 2006; Teasley et al., 2012).

School climate and context

SSWs reported adapting their SW practice to be successful working within a ‘host setting’ that is guided by educational policy and processes (Beddoe, 2019). Almost half (n = 19, 43%) of the included studies examined barriers and/or facilitators related to School climate and context. Of these, 38% reported barriers only (n = 16), <1% (n = 1) facilitators only and <1% (n = 2) both. Some SSWs reported a fundamental conflict at times between student and organizational needs of the school, prompting the question ‘Who is the client?’ (Phillippo et al., 2017; Webber, 2018). There was evidence that SSWs identified SW ethics and values as barriers pertaining to issues of confidentiality, privacy and best interest of the client; with school district policies (e.g. sexual health and religion) (Sawyer et al., 2006; Chanmugam, 2009; Quinn-Lee, 2014; Rueda et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2015; Phillippo et al., 2017; Webber, 2018; Daftary, 2022; Goodcase et al., 2022). SSWs reported barriers related to the school context and their location within the school landscape as a ‘guest’ in the ‘host setting’ and that school climate and internal dynamics shaped interprofessional relationships and collaboration and a schools’ response to issues (e.g. bullying) (Testa, 2012; Sawyer et al., 2006; Peabody, 2014; Miller et al., 2015; Phillippo et al., 2017; Beddoe, 2019; Goodcase et al., 2022). Some SSWs reported limited ability to meet with students during the school day given prioritisation of academics over student wellbeing (Blair, 2002; Peabody, 2014; Quinn-Lee, 2014). Some SSWs reported policy and bureaucracy barriers from district and administrative policies that were inflexible or inadequate in addressing the needs of vulnerable students (Crepeau-Hobson et al., 2005; Reid, 2006; Sawyer et al., 2006; Teasley et al., 2010; Lee, 2012; Oades, 2021). Some SSWs felt that having a system-wide united purpose and commitment, with rules and policies that supported SSW practice and addressed barriers to learning, facilitated SSW practice (Teasley et al., 2010, 2012; Miller et al., 2015).

Cultivating relationships and engagement

SSWs perceived that cultivating effective relationships, through consultation and collaboration with students, families, staff and the community was an essential facilitator for effective SSW practice (Beddoe, 2019; Daftary, 2022). Thirty-three (79%) of the included studies identified barriers and/or facilitators to SSW practice regarding cultivating relationships and engagement. Of these, 38% (n = 16) listed barriers only, 14% (n = 6) facilitators only and 26% (n = 11) both. SSWs reported that power imbalances and dynamics with school administrators were barriers to SSW practice (Chanmugam, 2009; Webber, 2018; Beddoe, 2019; Karikari et al., 2020). SSWs perceived a lack of agency and marginalization and that the relational dynamics influence a schools’ culture and norms, which in turn impacts SSW referrals and collaboration (Chanmugam, 2009; Testa, 2012; Miller et al., 2015; Beddoe, 2019; Karikari et al., 2020).

SSWs noted that interprofessional relationships, consultation and collaboration were barriers to SSW practice due to staff attitudes and expectations and disrespect for SSWs’ perspectives (Blair, 2002; Teasley, 2005; Sawyer et al., 2006; Mann, 2008; Teasley et al., 2008; Lee, 2012; Testa, 2012; Whittlesey-Jerome, 2012; Avant, 2014; Quinn-Lee, 2014; Gherardi and Whittlesey-Jerome, 2019; Elswick and Cuellar, 2021; Goodcase et al., 2022). Some SSWs experienced barriers resulting from inaccessible support or idiosyncratic relationships between multidisciplinary staff (e.g. school psychologists, school counsellors) (Reid, 2006; Lee, 2012; Peckover et al., 2013; Webber, 2018).

SSWs noted the importance of utilising relationship-based strategies in response to challenging relational and power dynamics, that strong and positive system-wide relationships with open-communication and consultation facilitated SSW practice (Teasley, 2005; Mann, 2008; Chanmugam, 2009; Teasley et al., 2010; Lee, 2012; Peckover et al., 2013; Avant, 2014; Peabody, 2014; Rueda et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2015; Avant and Lindsey, 2016; Beddoe, 2019; Johnson and Barsky, 2020; Heberle et al., 2021; Daftary, 2022).

Some SSWs were concerned with their ability to engage and cultivate relationships with students, families and the community. SSWs identified barriers associated with a lack of student and family engagement (Teasley, 2005; Reid, 2006; Sawyer et al., 2006; Teasley et al., 2008, 2010, 2012; Lee, 2012; Quinn-Lee, 2014; Rueda et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2015; Johnson and Barsky, 2020; Capp et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2021; Goodcase et al., 2022). Some SSWs found barriers to community engagement due to the accessibility of community supports/services, community misperceptions of SSW role, strained school relationships and community and environmental risk factors (Teasley, 2005; Reid, 2006; Sawyer et al., 2006; Teasley et al., 2010, 2012; Lee, 2012; Peckover et al., 2013; Rueda et al., 2014; Goodcase et al., 2022). There was evidence that SSWs perceived that positive formal and informal relationship building and collaboration and availability of community resources and referrals facilitated SSW practice (Teasley, 2005; Mann, 2008; Teasley et al., 2010; Quinn-Lee, 2014; Heberle et al., 2021; Oades, 2021; Daftary, 2022).

Discussion

By examining and synthesizing the barriers and the facilitators to SSW practice, this study demonstrates the challenges that SSWs experience and highlights the facilitators that support effective SSW practice. This review found that barriers to SSW practice were reported in greater detail than facilitators and a dearth regarding facilitators that were considered under the themes: Inadequacy of service delivery infrastructure, SSW role ambiguities and expectations, SSWs’ competency, knowledge and support and School climate and context. There was evidence that SSWs perceived that the barriers related to SSW role expectations and ambiguities, resulted in unrealistic workloads and significantly impacted SSWs’ ability to provide effective services. These findings support existing evidence that these barriers impact SSWs job satisfaction and intent to stay, and can result in burnout, compassion fatigue, vicarious trauma, absenteeism and attrition, which impacts SSW practice effectiveness and negatively impacts student and family outcomes in schools (Agresta, 2006; Caselman and Brandt, 2017). However, it is important to note that only a few included studies specifically referenced burnout in their results, with little to no discussion of their implications. With so little research regarding the barriers and facilitators to SSW practice related to compassion fatigue and burnout, this scoping review has identified a potentially important area for future research.

This study demonstrates the importance for SSW practice of cultivating effective interprofessional relationships and collaboration amongst school staff, students, families and the community to improve student and school outcomes. SSWs perceived that the barriers to establishing strong interprofessional relationships were related to significant SSW staff turnover, insufficient funding and time, schedule conflicts, high caseloads and servicing multiple schools (Bronstein et al., 2011; Lee, 2012; Miller et al., 2015; Drew and Gonzalez, 2021). These findings highlight the need to mitigate these barriers to ensure effective interprofessional relationships and collaboration and facilitate effective SSW practice to help students thrive.

An interesting finding is that SSWs in Daftary (2022) reported increased time, during COVID-19 school shutdowns, for planning and preventative work due to the absence of school crises and interruptions, which increased accessibility to students due to minimised interruptions and improved SSWs’ ability to better meet the needs of students and their families. However, there is little research identifying which facilitators support SSWs to overcome the barriers that prevent them from effective engagement, consultation and collaboration; and what facilitates their ability to respond to challenges, such as role conflicts, competing demands, unrealistic workloads and crisis-driven, reactive environments. Future research is warranted to explore whether the facilitators that were effective in supporting SSW practice during the COVID-19 school shutdowns have continued with the return to in-person learning, which may inform school leaders and SSW practitioners to develop practices that integrate these facilitators into ongoing SSW services and may provide important contextual information for SW educators to include in their preparation of new SSW graduates. It is also notable that the impact of natural disasters was not discussed in any of the included studies and provides an opportunity for future research contributions in this area.

This study highlighted the importance of school-context specific training, education and support as a facilitator to SSW practice, which can inform policy makers, school leaders and SW educators to better support SSWs so that they have the competencies and knowledge required to enhance student’s educational and wellbeing outcomes. Furthermore, the absence of any discussion in the included studies regarding the specialist SSW education programs available in the USA is interesting. Given the findings from this study highlight the importance of supervision and SW consultation in facilitating SSW practice, school leaders and SSWs must ensure that appropriate supervision and supports are available to ensure that SSWs are supported to effectively respond to the diverse needs of students and their families. However, given the paucity of information in the included articles regarding how SSWs navigate the barriers to accessing supervision and support, further understanding regarding the perspectives of how SSWs engaged creatively to overcome these barriers is warranted. Furthermore, little attention to the role of membership of an SSW specific association or SW licensure as facilitators to SSW practice indicates that further research into their role as a barrier and/or facilitator to SSW practice is warranted.

This review also highlighted the disconnect between the SW professional ethics/values and their experiences in practice within school settings. The lack of attention given to SSWs’ perspectives regarding their engagement with the SSW practice standards (where available) or SW Codes of Ethics to align their day-to-day practice, support their professional autonomy, decrease role discrepancy, resolve ethical dilemmas and support their interprofessional relationships, is an interesting finding in itself. This is important given that SSW practice standards and code of ethics provide a framework for effective SSW practice based on SW values and principals and are an important tool in legitimising the SSW profession (Altshuler and Webb, 2009; AASW, 2011).

Limitations

The scoping review as a methodology mapped the existing academic literature, and as a result, the quality of the evidence included was not assessed. Limiting the context to empirical evidence from USA, UK, Australia, Canada and Aotearoa New Zealand and excluding grey literature and non-English language articles, faces the risk of excluding a greater international perspective of SSWs. By including articles that aggregated responses from interprofessional staff, which prevented delineation of SSWs responses from other professionals, the findings may not purely reflect SSWs perspectives. However, the inclusion of these studies was preferred considering the risk of omitting important evidence arising from reducing the number of included articles to only those that solely focused on SSWs in the study sample. While this scoping review compared five countries that have similar structures of education, political institutions and colonial histories, this study does not take into consideration all contextual differences that exist within each country. It was also beyond the scope of this study to focus specifically on specialised SSW programming or on barriers and facilitators regarding SW practice with specialised populations. These limitations highlight important areas for further consideration.

Conclusion

This scoping review examined the existing academic SW literature regarding the barriers and facilitators to SSW practice. The five main themes are an extensive summary of the factors that inhibit or enable SSWs to provide effective services to meet the diverse needs to students, families and the school community. With so little evidence regarding the facilitators to SSW practice, specifically regarding how SSWs operationalise practice-based strategies and skills to overcome barriers to SSW practice, this scoping review has identified an important area for further research, particularly in countries where research is emerging. This article furthers the understanding of the barriers to effective SSW practice, which provides important contextual information to inform the development of policies and practices that social workers, school leaders, SW educators and policy makers can take into consideration to effectively facilitate SSW practice and enhance students’ wellbeing and ability to thrive in school.

Funding

This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at British Journal of Social Work Journal online.