-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sharanya Mahesh, Jason Lowther, Robin Miller, Improving Quality in Social Work: The Role of Peer Challenge, The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 54, Issue 4, June 2024, Pages 1719–1736, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcad252

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Network-based approaches to improvement and specifically, peer challenges have become an integral part of quality assurance in adult social work in England. Whilst the national regulation change in 2011 placed greater weight on local accountability, very few studies have examined the contribution of peer challenges towards improving the quality of adult social work practice. Peer challenge is a process of engaging a wide range of people and experienced peers in relevant service areas to offer a review from the perspective of a critical friend. This article considers how a regional peer challenge process in the West Midlands of England contributed to improving social work practice and processes, which supported this contribution. Drawing on data from fifteen interviews and forty-four survey responses, findings suggest that peer challenges in the short term can have positive impacts including, an understanding of the internal practice conditions and external context, strengths and limitations of social work practice, and the perspectives of local stakeholders and external peers on opportunities to improve practice. The design, commitment to transparency and trust by all parties enable honest reflection and a shared learning experience. To understand long-term impacts, we suggest establishing formal follow-up processes together with developing key baseline indicators to track impacts.

Introduction

Ensuring that social work is practised to an acceptable standard of quality is essential to improve outcomes for individuals and families, and to prevent situations of neglect and abuse. Responsibility for setting and assuring the overall quality of social work practice is commonly divided between numerous actors. These can include—professional bodies, sector regulators, national and/or regional policymakers, employer organisations and higher education institutions. The definition of what is considered ‘social work’, the exact nature of their responsibilities and the dynamics of how their roles interact, vary between countries (Worsley et al., 2020). The underlying principles vary from structural approaches based on institutional rules and processes (Andrews et al., 2008), neo-liberal-based performance management, competition and financial incentives, and network approaches based on common interests and informal relationships. In the UK, social work is defined as ‘social work is a practice-based profession and an academic discipline that promotes social change and development, social cohesion and the empowerment and liberation of people’ (International Federation of Social Workers, 2014).

Alongside assurance of basic standards are practical approaches to improve the quality of practice (O’Brien and Watson, 2002; Ahn et al., 2016). Social work is generally not as developed as healthcare professions, where quality improvement is more central within organisational infrastructure and professional responsibilities (Batalden and Davidoff, 2007). Staff supervision is the main improvement process, which English social workers deploy through encouraging reflection and constructive challenge (Ravalier et al., 2022). Other approaches include audit (Munro 2004), appreciative inquiry (Research in Practice for Adults, 2019) and plan-do-study-act cycles (Miller et al., 2015). Organisational culture will influence if social workers feel safe to share errors and enable learning, or to prevent such contributions if they experience a blame climate with individual scapegoating and sanctions (Munro, 2011). There is also a crucial role for people with lived experience in setting the aims and standards of social work, to reviewing current practices and developing opportunities for improvement (Elwyn et al., 2019). Whilst such co-production is broadly supported in principles, and indeed is embedded within the main legislation that guides work with adults (Department of Health, 2014), there remain too few examples of it being embedded in quality assurance and improvement processes (Wood et al., 2022).

Since 2019, Social Work England (SWE) has had legal responsibility for setting professional and educational standards and establishing processes through which individuals are formally registered and deemed as ‘fit to practice’. Only professionals actively registered with SWE are legally able to use the ‘protected title’ of social workers in their practice. The Office of Chief Social Worker for Adults (CSWA) (2019) has the responsibility to provide national support and challenge for the profession (in collaboration with their counterpart in Children and Families). Other key bodies include The British Association of Social Work (which developed an overarching professional Capabilities Framework) and the Principle Social Worker (PSW) Network (Adult PSWs have responsibility for leading practice in their organisations). There has also been a tradition of governmental agencies (most latterly the National Audit Office) (Murphy and Jones, 2016) undertaking quality assurance of local authorities in relation to their lead responsibility for adult social care, including as the main employer of social workers. The term adult social care in the UK denotes the sector of agencies who care manage and deliver care and support services. In 2011, as part of an austerity drive, the government introduced a new approach that emphasised local accountability rather than national inspection (Ferry, 2016). The Local Government Association (LGA), the national membership body for local authorities were tasked with developing sector-led improvement (Murphy and Jones, 2016).

This was based on network principles—councils are responsible for their own performance and improvement; accountable to their local communities; and share a collective responsibility for the performance of the sector. Alongside generic activities, the LGA developed a ‘Towards Excellence in Adult Social Care (TEASC) programme’ focused on this sector. Children’s social work also has sector-led improvement led by the LGA (Bryant and Rea, 2017), but this is undertaken alongside external scrutiny by the National Department for Education and the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted).

Central to sector-led improvement processes are ‘peer challenges’—in which expert peers review the practice and organisational processes of a local authority (LGA, 2012). Alongside those facilitated by the LGA (for which there was a fee), local authorities could organise their own peer challenges. The Directors of Adult Social Services (WM ADASS) in the West Midlands (a region within the centre of England incorporating fourteen local authorities) developed their own version in 2015. Directors of Adult Social Services (DASSs) are senior managers with legal responsibilities for adult social care services (including social work with adults) in their locality. This was on the basis that a local approach would generate greater opportunities for sharing of learnings and develop stronger networks. Moreover, this process could be managed within the existing resources of the local authorities and not encounter an additional fee.

This article is based on a formal evaluation which sought to answer two questions: (1) what were the stakeholders’ perceptions of the contribution of peer challenge to assuring and improving the quality of adult social work practice and (2) what were the main processes through which these contributions were achieved and how could they be strengthened in the future?

The WM ADASS peer challenge programme

Commissioned by the host DASS and organised by WM ADASS, the peer challenge process initially involved the review team interviewing a range of stakeholders (including staff at various levels, people with lived experience, family carers and external organisations) and then reporting on the key strengths, areas from consideration and recommendations from improvement.

Since undertaking the first set of peer challenges in 2015, the WM ADASS peer challenge programme has been amended to reflect the changing priorities and context for adult social work. Initially, its scope primarily focused on the implementation processes of the Care Act 2014, the major piece of legislation of adult social care. Over time, the peer challenge programme shifted its focus on embedding strengths-based practice to improve outcomes and achieve greater value for money. More recently, the programme included the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on the workforce and quality of services.

The composition of the peer challenge team and elements of the peer challenge process have undergone changes over time. These have included the introduction of self-assessment forms and practice reviews (more details below). Another iteration involved the inclusion of people with lived experience termed as ‘experts by experience’ to be a part of the peer challenge team. They are recruited through local authorities’ lived experience groups with interested volunteers provided information about the process and their role by WM ADASS alongside training. Their lived experience can include having received services themselves and/or having taken on a caring responsibility.

Below we describe the current iteration of the peer challenge in three stages—pre-peer challenge, during the challenge and post-peer challenge.

Pre peer challenge

The WM ADASS lead for the peer challenge liaises with the DASS in each local authority to schedule its next peer challenge within the regional cycle. Prior to undertaking a review, the host organisation is required to complete the self-assessment form along with the risk assessment tool developed by TEASC. The self-assessment form includes six key areas—use of resources; strengths-based; safe and integrated practice; leadership and partnerships; performance and experience; market sustainability and quality; and improvement and challenge. In addition, the local authority shares a mandatory list of strategic and performance documents along with any other documents or information they see as relevant. To ensure that there is sufficient exploration and capture of social work practice, the PSW network in the region developed a practice review process. This involves two PSWs from other local authorities working with the host area PSW to examine a sample of adult social work case files, hold a series of focus group discussions, and share recommendations around practice conditions. The process is undertaken a few weeks prior to the peer challenge programme with findings shared with the peer challenge team. Over the years, practice reviews have become an integral part of the challenge process (Godfrey and Mahesh, 2022).

During the peer challenge

Having pre-read the documents, the peer challenge team spent three days in the host local authority. The peer challenge team includes a representative from WM ADASS who acts as the overall lead, a politician from another local authority with an adult social care portfolio, two senior managers of adult social services from other local authorities in the region and at least one expert by experience. All team members meet with staff and service user groups and contribute to the final report. The lead of the review team has the responsibility to oversee that the peer challenge follows the agreed processes and is balanced in its assessments.

The team meets with a sample of frontline practitioners, managers, care providers, external agency partners and people with lived experience. These meetings are held in groups of six to eight people and in the absence of senior leaders to enable sharing of honest opinions. At the end of each day, informal discussions are held between the lead and host DASS to reflect on emerging insights.

On the final day, overall findings are first presented to the host DASS and other senior leaders, such as the Chief Executive. This is an opportunity for the host to correct any factual inaccuracies and seek clarification. They are able to provide their perspective on the findings and recommendations—whilst these will be considered by the review team, they ultimately have the discretion to finalise their report. These will then they shared within the wider local authority including the PSW.

Post peer challenge

It is expected that the host authority publishes the findings along with the recommendations on their website and share outcomes with wider partners. An informal follow-up after six months is scheduled between the host DASS and the lead of the peer challenge team to review progress with the implementation of recommendations.

Methodology

Research design

The overall aim of the evaluation was to understand stakeholders’ perceptions of the contribution of the peer challenge to assuring and improving the quality of adult social work practice and, the main processes through which these contributions were achieved.

To address our research questions, we adopted a convergent mixed methods design in which qualitative and quantitative data were collected (within a similar time period) (Doyle et al., 2009). This enabled corroborative analysis of both data sets and therefore, a comprehensive view (Alasmari, 2020) of the perceptions of the participants in the peer challenge process.

Data were gathered through semi-structured interviews and an online survey with a sample of practice, managerial, political and lived experience stakeholders. The topic guide for the interviews and survey questions was developed by researchers in collaboration with WM ADASS based on the overarching purpose of the study and key lines of enquiry identified through a rapid review of the literature. All interview participants were asked the same set of questions but not in a set order. This enabled flexibility and the open-ended nature of the questions facilitated a more focused exploration of the topic and raised opportunities for follow-up on emerging issues (Hewitt, 2007). The topic guide was divided into three categories—process, impact and learnings from the peer challenge. Questions, such as ‘what did you expect the benefit of the peer process to be’ and ‘how would you describe your experience in the process’, were asked alongside requesting specific examples to improve the richness of the data collected.

Topics within the survey included the respondent’s experience of the peer challenge(s) and any training received, their job role, their perception of the cost–effectiveness of the peer challenge at improving the quality of care, the involvement of people with lived experience, post review involvement, long-term impacts and wider regional learning. The survey also provided an opportunity to provide free comments in multiple places. A pilot of the survey confirmed its practicality and led to minor clarification of the wording of some questions.

Data collection strategy

Data were gathered over a period of four months between December 2020 and March 2021. A total of fifteen interviews were conducted with different stakeholders—PSWs, DASSs, politicians with the brief for adult social care and three interviews with people with lived experience who had participated in the peer challenges. Interviews were conducted via various virtual platforms, such as Zoom and Teams, and were digitally recorded. The average time for each interview was about sixty minutes.

Recruitment of participants for the interviews and the survey were in collaboration with WM ADASS. In the case of interviews, the research team was provided with a list of stakeholders who have participated in peer challenge process, and they were sent an introductory email explaining the purpose of the study. Upon confirming their interest to participate, a project information sheet detailing various components of the study along with a consent form was sent. For those non-responses, a follow-up email was sent three weeks after the initial email and a similar procedure was followed when met with a positive response.

The invite to participate in the online survey was directly distributed by WM ADASS. Respondents were initially given two weeks to return their responses, but the deadline was subsequently extended for an additional week. Prior to recirculation, a total of fourteen responses were recorded, which increased to forty-four by the closing date. The survey, like the interviews captured responses from the different stakeholder groups, that is, senior leaders—including DASSs, politicians, leaders of other local authority functions, such as directors of public health, PSWs, middle managers and people with lived experience.

The initial analysis, themes and their implications were shared by the research team at a workshop facilitated by WM ADASS. This was attended by a variety of senior social work practitioners and managers who provided their perspectives on the extent to which the findings reflected their experience and their view of the main implications.

Data analysis

Interviews and open-ended questions from the survey were analysed inductively through thematic analysis. A range of themes emerged around participants’ perceptions about the use of different data sets, the ability to provide practical and meaningful recommendations and mutual benefits for the review teams and host local authority. Thematic analysis was undertaken based on Braun and Clarke’s six-stage thematic analysis framework (Nowell et al., 2017). The first stage involved the researchers familiarizing themselves with the data followed by stage two, that is, generating initial codes. The initial set of coding was done independently by two. These were discussed extensively to arrive at a common set of themes that the team was in agreement with. The third stage involved identifying themes followed by stage four of reviewing themes and stage five involved defining and naming themes (Nowell et al., 2017). The last stage of the process involved producing a report and sharing widely with partners.

The survey was analysed through descriptive statistics using the Qualtrics survey analytical functions. Close-ended questions were analysed quantitatively. Cross tabulations were generated for question responses in order to check for significant differences between participants such as job role; however, analysis was not presented by professional groups as differences were not significant and the study’s main aim was to understand the overall impact on practice rather than perceptions of specific professional groups. The study mainly used frequency tables and charts.

This article integrates results from the analyses of separate data components. Findings from the interview data and survey responses were triangulated to determine the ‘fit’ between the two data sets. Codes emerging from the interviews were mapped to similar themes within the survey responses to determine confirmation or discordance. In doing so, we were able to validate our findings and examine reasons for any contradictions that may have arisen.

Ethical approval

Approval for the study was obtained from the University of Birmingham’s ethics committee. Ethics Application ERN_13-1085AP38. All participants have consented to take part in the study.

Findings

The overall perception of participants was that the peer challenge process has contributed positively towards improving the quality of local adult social work practice and wider social care services. Findings are presented under three themes although we note connections between all the themes. Direct quotes from research participants have been included as an illustration of the wider findings, to present their views in their own words (Patton, 2002) and researchers’ interpretation of findings (Sandelowski, 1994).

Value at the organisational and professional level

Most participants shared a range of benefits that emerged from being part of the peer challenge process. These included a more comprehensive understanding of the internal practice conditions and how these were influenced by the external context, the strengths and limitations of current social work practice and interactions with adults and families, and the perspectives of local stakeholders and external peers on opportunities to improve. The peer challenge was described as generating momentum for change and providing practical recommendations for what the change could include.

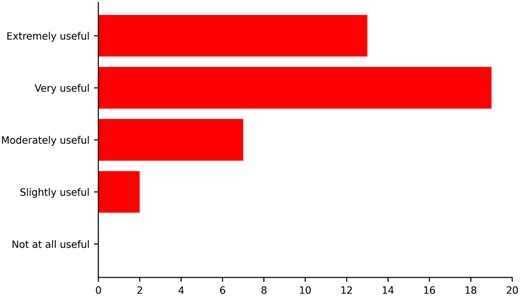

Nearly 80 per cent of survey respondents reported that the peer challenge process was ‘extremely useful’ or ‘very useful’ in improving the quality of practice in the host local authority in the short term (Figure 1), which suggests that they perceived considerable value was gained from engaging in the process. The perception declined to 58 per cent when asked about the impact of the peer challenge process in the long term. It is not clear if this reduction was due to a lack of information on which to base such an assessment (e.g. members of a challenge team who had not returned to the authority for subsequent reviews or insufficient time passing to be able to judge long-term impacts) and/or if respondents had sufficient information but not observed sustained impacts. Another issue could be the focus of the peer challenge on the practice conditions and external environment at the time of the review as these can be subject to internal restructurings or changes in financial and policy environments.

Usefulness of the peer challenge in improving the quality of care in local authority reviewed.

At the strategic level, the peer challenge provided valuable information and recommendations about practice conditions, such as culture and leadership that contribute to shaping and improving services. Additionally, they were an opportunity to consider external influences and engage in broader discourse on the political and socio-economic landscape. The following quotes illustrate the importance respondents attached to understanding external contexts and providing an opportunity for reflection.

It’s really important to understand the impact of things like austerity, changes in policy, changes in legislation, and finally I think it’s really important to do that in a way that is structured and regularised because without that, I think the genuine risk is that it just disappears into the regular and wider pressures. (DASS 1)

I think there’s two things that are good about it, one, I think it gives officers in the local authority but also visiting officers a chance to reflect on practice, to reflect on policy, to reflect on what’s actually happening in that area of their local authority. People don’t often have a chance to do that, people are on a treadmill and they’re running, running, running. (Expert by experience 2)

Some participants valued that the process provided a balanced perspective that recognised and appreciated areas of good practice but equally picked up on areas of weakness, such as poor multidisciplinary working, insufficient communication between different services and misalignment between the interests of senior management and frontline staff. Most respondents further added that reviewing case files as part of the process provided insight into how practitioners engage with service users.

Somebody outside from another organisation looking in. And they’re not just scratching the surface, they’re going in to look at what is the most important part of our function, it’s those conversations, those cases, that recording, that we’re keeping in respect of, you know the real-life people that we’re there to support. (PSW 1)

So, they got this programme up and running that they wanted us to feedback on and the top level like, great, brilliant, absolutely wonderful, no problems at all. Yet when you’ve got the frontline and partner organisations, some of them didn’t even know what it was. (Politician 2)

However, the extent to which a realistic understanding about practice was captured depended on the commitment of the host authority to the process. Some participants shared examples of ‘lack of preparedness’ including insufficient background information and limited engagement from stakeholders. A related issue was the extent to which the host authority was willing to be honest and open about their practice conditions to the peer challenge team.

I’ve gone in on peer challenges where the local authority’s put in the absolute bare minimum of effort. They haven’t briefed the people that you're going to speak to about what the purpose of the exercise is, I walked into a room in one authority that have 40 people who use parent support, they didn’t know why they were there, they were worried that their payments were going to be stopped if they didn’t go. They were angry, they were fed up. (DASS 3)

It is important that people came forward and be honest with the challenges they are facing. (PSW 2)

Personal learning from the peer challenge

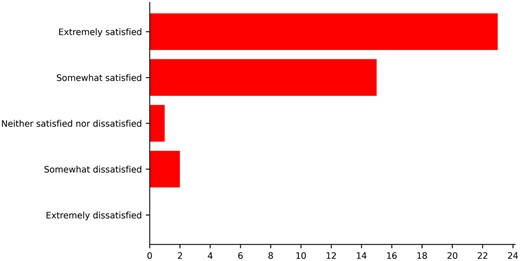

Nearly 93 per cent of survey respondents who had been members of a review team were ‘extremely satisfied’ or ‘somewhat satisfied’ with what they had personally gained from their participation (Figure 2). It was reported that nearly 90 per cent of respondents learnt something new from the process and more than 50 per cent (53 per cent) shared that they gained wider learning about adult social work and social care in the region.

Satisfaction levels of peer challenge team members on personal benefits from the process.

The interview findings corroborate these gains as participants reported that the peer challenge process was in ways, a ‘reciprocal’ process enabling benefits for the local authority and the members of the review team. Opportunities for the host authority to reflect occurred at different stages of the process—undertaking the self-assessment, having daily feedback with the review team, being engaged in sessions and discussing the final recommendations shared by the peer challenge team. The peer challenge team found that participating in the process helped them reflect on practice conditions in their own local authority.

It’s a really good thing for any senior manager to do because it makes you ask yourself questions about your organisation, how you’re doing stuff, and I think you can get lots of good ideas. (DASS 2)

Holding a mirror up to people themselves and people using the process to reflect on what’s under their noses really. (PSW 2)

Most participants felt that they were part of a ‘shared learning’ experience. For the members of the peer challenge team, the general perception was that the process enabled them to gain new perspectives and ideas, and solutions to problems that could be replicated in their own council. We also noted that the process appeared to provide a sense of validation and assurance to both the host council and the peer challenge team about overall challenges experienced by local authorities in the region and how these affected social work practice conditions.

By going to another authority, seeing how things work there and asking physical questions, it gives a huge amount of development. So, when my portfolio holder went up to participate … he came back and he had a shopping list of three pages, what are we doing about this, what are we doing about that, brilliant because what he’s doing, is forensically and critically thinking about his need to know the information. (DASS 3)

So, I think it’s a process that gives them a reality from what I could see. It asked them to question themselves while being questioned by others, which is a good thing I think. (Expert by experience 1)

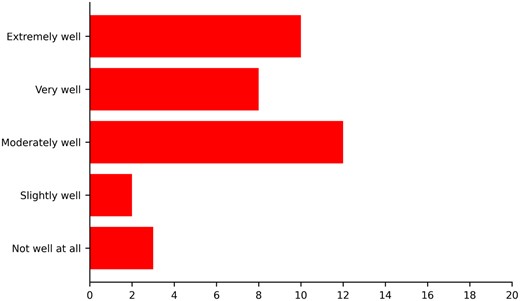

Coproduction

As outlined above, WM ADASS adapted their initial peer challenge process to involve people with lived experience. Just over 50 per cent of survey respondents shared that people with lived experience were ‘extremely’ or ‘very’ well involved with others feeling less positive towards their engagement (Figure 3). Interviewees agreed that experts by experience were an important part of the peer challenge process and recognised the varied roles they played. As a member of the evaluation team, participants recognised increased ‘quality’ and ‘power balance’ in conversations between experts by experience and service users in the host council. However, there were concerns raised around them being treated as ‘equals’ with other members of the peer challenge team which may have had repercussions around the level and extent to which experts by experience could actively contribute.

When that individual was out and about and talking to people who were receiving care and support, it was a different conversation. It was an aired conversation, it was an equal conversation, there wasn’t a professional speaking, it wasn’t anywhere near as formal but also the feedback that he gave was very direct. (DASS 1)

I didn’t quite know what authority I had to speak up sometimes. You’ve got all these –it’s that feeling of am I alright to say what I think here because all these people with their suits and their folders and their data, they like their data, and they were all very- they’d got all the jargon and they all lived and worked this. (Experts by experience 3)

Extent to which people with lived experience were meaningfully involved.

Discussion

A robust and explicit approach to the regulation of professions and the organisations that employ them is a common approach for governments to ensure a minimum quality of practice, including within social work (Worsley et al., 2020). Over the last decade in England, there was a push towards network-based approaches replacing top-down regulatory frameworks (Murphy and Jones, 2016). Since the development of the new sector-led improvement approach by the LGA, peer challenges have become the central plank (Miller et al., 2021) to such improvement offers (LGA 2012; LGA, 2018; Shared Intelligence, 2019). In contrast to risk-based approaches as deployed by external regulators, peer challenges have been promoted by LGA and others as providing flexibility to local authorities to undertake reviews at a time most suitable for them and focus on aspects most relevant to them (LGA, 2016). This article has sought to address the current lack of objective empirical evidence around the impact of improvement approaches in social work.

Our findings show that when implemented robustly, a peer challenge process can provide valuable insights into practice conditions and outline the main opportunities for improvement within the political, social and financial context. The peer challenge process shares elements of social work improvement approaches used within other countries such as case reviews of process and outcomes (e.g. Milner et al., 2001). The distinct aspect is the review process being undertaken by peers rather than an agency to which the social work agency has accountability, which provides peer expertise and a sense of reciprocal learning (Ahn et al., 2016). Fundamental to the process are the peer challenge teams’ capability to create an environment for social work practitioners in the host councils to be honest and voice their opinions (Mannion and Davies, 2015) and the level of preparedness and willingness of the host local authority to be transparent.

When studying the effectiveness of peer challenges in wider public services, much has also been written about the quality (LGA, 2018) and composition (Shared Intelligence, 2019) of the peer challenge team. Within the WM ADASS approach, the integration of practice, manager and political expertise provided more diverse and therefore deeper level of insights. This included in later iterations the involvement of experts by experience in peer challenge teams. The extent of coproduction appears to depend on role clarity and confidence of the experts but equally, how much space and recognition was given by other team members to their perspectives (Armstrong et al., 2013). Where teams were well integrated, we note that issues, such as power imbalance (Hollins, 2019) and tokenism (CFE Research, 2020), were avoided with sharing of insights and experiences. However, such equality of involvement was not always achieved, reflecting a wider critique of co-production in policy and quality improvement processes, with experts by experience being asked to comply with processes developed by professionals and being confident in their scope to challenge the perspectives of others (Needham and Carr, 2009; Beresford, 2019).

Ensuring that all members of the review team are aware of and committed to the contribution of experts by experience, that all members have received appropriate training and support in how to translate co-productive principles in practice, and that experts by experience can see tangible outcomes from their contribution would strengthen this aspect considerably (Clarke et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2023).

Benefits from the process are not only for the host organisation but extend to the peer challenge team itself (LGA, 2018). Peer challenges are a platform for team members to reflect on practice conditions in their own organisations, recognise similar challenges and take back new ideas for commonly experienced problems. Undertaking within a region helped to develop local relationships and networks and foster wider learnings and improvement opportunities. Despite these advantages, the lack of a formal follow-up process and flexibility for the host organisations in how to share findings prevents evaluation of the long-term impacts. Moreover, the general lack and adequacy of data in adult social work and social care in the UK (Cream et al., 2022) creates further challenges to determine the impacts of such improvement processes. Developing a formal follow-up process along with baseline of key measurement indicators would support accountability of the host local authority to their improvement plan and provide additional learning for the review team.

Limitations

The study has two notable limitations. First, there may have been a risk of selection bias as recruitment for interviews and survey responses were undertaken through WM ADASS. A more inclusive approach, such as making direct contact with councils and/or social work practice networks in the region for recruitment, would have mitigated the risk of selection bias.

Secondly, given the timing of data collection (during the pandemic) and the duration of the study, all interviews were conducted over digital platforms. It provided limited opportunities to develop a rapport with participants, which may have had an impact on the willingness of participants to share information more freely. Under normal circumstances, we would have liked to observe peer challenges in real time to capture rich data around processes and interactions during the challenge. From a methodological viewpoint, incorporating an element of observation in future studies can help obtain robust information about the process. Conducting longitudinal studies may also be beneficial in enabling to widen the evidence base on long-term impacts of sector-led improvement initiatives.

Conclusion

Debates on best approaches to quality assurance and improvement of social work services will continue to be of interest to the sector, policy makers and the public. Our findings suggest that peer challenges are a useful tool to improve adult social work practice. Unlike top-down structural approaches, a network process can be adaptable to the local context, build on professional and lived experience expertise and develop a culture of reciprocity and openness between peers. By developing and coordinating a shared process that had buy in from senior leaders in local authorities, the WM peer challenge had enabled local authorities gain valuable insight about their social work practice from peers who are aware of the context and pressures within which adult social work services operate. Going forward, local authorities in England will have to adhere to a new assurance process for adult social care that will include assessment visits set by a regulator (Care Quality Commission, 2023). Peer challenges, when implemented well, will be an effective tool to help local authorities prepare for such assessments but there is a danger that they become crowded out by the national approach. It also to be hoped that the benefits from a networked and voluntary approach to improvement in social work will be adapted into new and co-produced opportunities for peer challenge, which build on the profession’s commitment to achieving quality of practice and its shared values. Embedding knowledge and skills of shared and co-produced improvement processes within qualifying and management education programmes would also help to develop awareness of their benefits and encourage more widespread deployment and innovation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the West Midlands ADASS for their valuable insight and support.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Funding

This research is funded by the National Institute for Health and Care research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaborations (ARC) West Midland. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.