-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lorraine Swords, Trevor Spratt, Holly Hanlon, Professional Burnout as a Mediator in the Relationship Between Pandemic-Related Stress and Social Care Workers’ Mental Health, The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 54, Issue 1, January 2024, Pages 326–340, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcad198

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Understanding pathways between social care workers’ Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19)-related stress and poorer mental health outcomes can inform employers’ efforts to support the well-being of staff. The present study engaged 103 workers at an Irish Non-Government Organisation providing child and family support services. In the initial months following the cessation of pandemic restrictions in 2022, they completed an anonymous online survey that included questions about their experiences of COVID-19, their professional quality of life and their mental health. The aim was to explore the direct effect of COVID-related stress on workers’ mental health, and the indirect effect through the mediators of compassion satisfaction and the compassion fatigue components of burnout and secondary traumatic stress. The results indicated that greater levels of pandemic stress are significantly and directly related to both increased burnout and poorer mental health, and that burnout also partially mediates the relationship between pandemic stress and poorer mental health. This study adds to a growing body of work concerned to better understand the social care workers’ pandemic experiences, and results are discussed in terms of apprising employers of the need for timely and effective staff supports.

Introduction

The global Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has generated a concern to better understand its impact upon professional groups working directly with the public. Much of the extant research has focused on the experience of health workers who offered in-person face-to-face services over the course of successive pandemic waves. These studies have documented the fallout of juggling the increase in workload with managing the risk of infection, amongst other new and complex pandemic-related work challenges, with workers reporting psychological symptoms, such as fear, insecurity and anxiety (e.g. Montemurro, 2020; Shanafelt et al., 2020), along with work-related burnout and secondary traumatic stress (e.g. Ruiz-Fernández et al., 2020).

Less research attention has been given towards understanding the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of social care professionals who continued to provide key essential services to vulnerable populations throughout various phases of the pandemic. During more typical times, the nature of their work exposes social care workers to stressors that can strain their psychological and professional well-being (e.g. Newell and MacNeil, 2010; Pérez-Tarrés et al., 2018). However, with the pandemic adding to the psychological burden of clients, increasing demand for services, and requiring these services to be delivered in new, alternative ways to accommodate lockdowns or other infection control requirements, working pressures intensified for many. Added to this are the personal COVID-19 experiences of personnel who, as with others, are concerned for the health and general welfare of themselves and their loved ones (e.g. Coto et al., 2020).

This study centres on understanding the impact of COVID-19, particularly the effect of stressful pandemic experiences, on the mental health of social care workers and their service managers employed by an Irish Non-Government Organisation (NGO) delivering a range of family support services. As with many organisations delivering services of this type during the course of a pandemic, there was a concern on the part of the NGO to better understand both the immediate effects on staff, and their sequelae. However, research in this area remains in its infancy and there is a particular need to better understand the trajectories between stressful experiences and later mental health outcomes. To address this lacuna, this study aims to investigate whether aspects of professional quality of life, such as burnout, have a role in mediating this relationship. Understanding pathways between pandemic-related stress and poorer mental health outcomes is required in order to support workers’ well-being and respond to situations of compassion fatigue and emotional distress.

The impact of the pandemic on social workers and social care professionals

A recent report, Work-related stress, anxiety or depression statistics in Great Britain (HSE, 2021), states that rates of self-reported stress are increasing across the workforce, with professional groups, including social workers, reporting the highest levels of workplace stress. If we are to properly assess the impact of the recent pandemic on social work and social care professionals, it is important to take care to position them in terms of pre-existing exposure to work-related stress and its consequences. To this end, a survey carried out by McFadden, Measuring Burnout among UK Social Workers (2015), found that seventy-three per cent reported high levels of emotional exhaustion. It might be reasonable to suggest, therefore, that this is a professional group who entered the pandemic already with high levels of work-related stress. This might help explain the somewhat counterintuitive results found by McFadden et al. (2022) concerning Mental well-being and quality of working life in UK social workers before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. In this large scale survey, the researchers found that there were indications that mental well-being and quality of working life actually improved for a majority of workers over the course of the pandemic. Working largely at home, the ceasing of the daily commute, and the additional time spent with family had provided benefits.

Similarly, a recent Canadian study reporting The impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on social workers at the Frontline (Ashcroft et al., 2022) found that, overall, pandemic-related changes in working arrangements generated an increase in emotional well-being. It would seem, therefore, that whilst social workers may have carried high levels of occupational stress prior to the occurrence of COVID-19, the impact of the pandemic, resulting in recourse to virtual contact with service users, has created something of a unique natural experiment. Early extant research findings are indicating a differentiated pattern of impact, whereby these arrangements have reduced levels of stress for some, whilst increasing it for others.

An examination of the Ethical challenges for social workers during COVID across a number of countries by Banks et al. (2020) provides some indication for this latter outcome of increases in occupational stress. This report highlights the difficulties social workers experienced while working from home. To provide a specific example, infection-control ‘stay-at-home’ orders during COVID-19 that confined victims of domestic violence and abuse to the same households as their perpetrators resulted in increased incidence of violent and abusive behaviours (Bradbury‐Jones and Isham, 2020; Kourti et al., 2023; Piquero et al., 2021). Professionals working in this field have identified multiple additional challenges to their work, including concerns about not having the capacity to meet the demand of the workload (Foster, 2020) and clients’ compromised privacy and safety when services were conducted remotely using telephone or online platforms (Carrington et al., 2021). These were in addition to more personal COVID-19-related apprehensions related to their own health, isolation, fear for the future and working from home alone without the usual social and professional supports (Carrington et al., 2021).

Such findings, of course, are not restricted to those working in a social care or social work capacity with children and their families. For example, a study by Sheerin and colleagues (2023) reported that professionals who were supporting people with intellectual disabilities during the pandemic also encountered work-related challenges (e.g. overwhelming workload and concern for clients’ missing their routines), as well as issues with their own mental health and well-being (e.g. anxiety, sleep disturbance). The authors also note how, ‘…perceived professional commitment and associated willingness to push on with a brave face may have left staff vulnerable to mental health concerns’ (p. 5).

Burnout

Whilst a growing body of research highlights the compassion satisfaction—positive effects, a sense of fulfilment or pleasure—that some workers experience from helping vulnerable others (e.g. Arnold et al., 2005), repeated, ongoing, and high levels of work-related stress have long been associated with increased burnout (e.g. Maslach, 2003). Burnout is a psychological condition that results in exhaustion, frustration and a lack of work-related drive, motivation or interest. In addition to the personal effects of burnout for professionals in the social care and social work realms, the negative impact on professional functioning and subsequent lower levels of client care are key concerns (Ostadhashemi et al., 2019). Joshi and Sharma (2020) highlight how the job demands-resources model (Bakker et al., 2014) provides a compelling case in explaining the risk of burnout amongst mental health practitioners during COVID-19, when job demands are high and job or personal resources are limited or constrained.

Burnout is conceptualised as one of the two key components of compassion fatigue in the widely used Professional Quality of Life (PROQOL) measure (Stamm, 2009). The other component is secondary trauma, which can occur when helpers experience emotional distress following exposure to service users’ accounts of their direct traumatic experiences. As such, compassion fatigue has been referred to as the ‘cost of caring’ for others in distress (Figley, 2002). Indicators of occupational stress are an important public health concern.

The study

Whilst the studies identified above indicate a differential response to pandemic work conditions in terms of stressful impact, the pathways linking an increase in stress to an impact on mental health remain unexplored in the provision of social work and social care services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Research is, therefore, required to understand these pathways in order to support workers’ well-being and respond to situations of compassion fatigue and emotional distress.

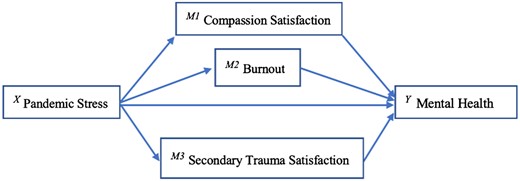

The present study aims to examine the professional quality of life and mental health of workers employed by an Irish NGO providing a range of child, parent and family supports in Dublin, Ireland, in the post-lockdown period of COVID-19. It further aims to explore the relationships between COVID-19 stress and workers’ professional quality of life and mental health. Specifically, this study tests a conceptual model (see Figure 1) of the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19-related stress on mental health through compassion satisfaction and the compassion fatigue components of burnout and secondary traumatic stress.

Conceptual model of the mediating roles of professional quality of life variables in the indirect effect of pandemic stress on mental health.

The study was commissioned by the NGO’s senior management team who were concerned to gauge the possible effects of the changes in working practices generated by the pandemic, including the possibility of increase in worker stress. The objective was to use the findings from the study to further inform their response to any emerging needs. A research team based at Trinity College Dublin, with previous experience of working with the NGO (e.g. Monson et al., 2022), was** commissioned to carry out a workforce survey.

Method

Study setting and participants

In March 2020, in response to the national and international crisis posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Irish Government introduced the Health (Preservation and Protection and Other Emergency Measures in the Public Interest) Act 2020. Part of this Act related to restrictions to prevent or minimise the spread of infection. This Act ended in March 2022, and with it all COVID-19 restrictions outside of hospitals and medical settings.

Between May and June 2022, 103 staff at the NGO completed an anonymous online survey that included questions about their experiences with COVID-19, their professional quality of life and their mental health. Workers were involved in therapeutic (n = 72) and management or administration (n = 31) roles at centres providing services focused on early childhood (n = 36), family support (n = 45), assessment (n = 18) and domestic violence intervention (n = 4). Just under fourteen per cent of the sample (13.6%) had been with the service less than two years, whilst nearly forty percent (39.9%) had worked there between two and ten years. Almost half of the sample (46.6%) had been with the service over eleven years.

During more typical times, services were delivered in person by way of a range of needs-led, strengths-based therapeutic supports to children and their parents/carers, such as individual and family work, parenting programmes, home visits, outreach and drop-in facilities. However, with the advent of the pandemic and related lockdown periods, in common with many organisations, the mode of service delivery changed. In many instances, workers delivered assessment, family support and therapeutic sessions from their own homes directly, via computer with online video calls, to the homes of service users.

Materials

A survey tool was developed which first asked staff to report in which service of the NGO that they worked and for how long they had worked there. They were also asked if they had worked in a similar service before joining this particular NGO. Data on age, gender or ethnicity were not collected, as this information had the potential to remove anonymity in some of the services. A package of standardised measures was collated and included the following.

Professional quality of life

Professional quality of life was assessed using the 30-item PROQOL Scale (Stamm, 2009). One subscale measures Compassion Satisfaction, which relates to the pleasure derived from being able to help others and do your work well. Compassion Fatigue is measured by two subscales: the Burnout subscale (which measures exhaustion, frustration, anger, depression, etc.), and the Secondary Traumatic Stress subscale (which measures negative feelings driven by fear and work-related trauma). On each subscale, scores can range from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating higher levels of the dimension measured. A score of 22 or less is considered low, between 23 and 41 average and 42 or more high. The reliability of the PROQOL in the present study was good, with Cronbach's alpha for burnout and secondary traumatic stress at 0.784 and 0.786, respectively, and compassion satisfaction at 0.811.

General mental health

The Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5; Berwick et al., 1991) refers to the past month and asked workers to estimate, for example, how much of the time they were ‘calm or peaceful’ or ‘nervous’. The six-point response scale ranges from ‘none of the time’ to ‘all of the time’. Scores can range from 0 to 100, where a score of 100 indicates optimal mental health. A cut-off point of 72 or lower is indicative of mental health problems (e.g. Hoeymans et al., 2004). The reliability of the MHI-5 in the present study was good, with Cronbach’s alpha at 0.793.

Pandemic stress

COVID-19 stress was measured using the Pandemic Stress Index (Harkness, 2020; Harkness et al., 2020). Participants were asked to respond ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to whether or not they had experienced each of nineteen items; sixteen relating to COVID-19 stressors (e.g. ‘Fear of getting COVID-19’) and three relating to positive experiences associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. ‘Getting emotional or social support from family, friends, partners, a counsellor or someone else’). The total score reflects the number of COVID-19 stressor items and positive items experienced in total, with the highest potential scores being 16 and 3, respectively.

Ethics

Ensuring that workers’ participation in the research was voluntary and that those who got involved, and their responses, would be anonymous, were amongst key ethical issues considered when designing the study so that it conformed to internationally acceptable research and professional ethical guidelines. Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of Trinity College Dublin’s School of Psychology.

Procedure

A survey was developed as detailed above and an invitation to all of the NGO staff to participate was issued in May 2022, along with a participant information pack. Surveys were administered anonymously online by way of Qualtrics and took approximately fifteen minutes to complete.

Analysis plan

Preliminary descriptive and correlational analyses were conducted in SPSS version 27. The conceptualised mediation model in Figure 1 was assessed using PROCESS (Hayes, 2018, model 4). Length of time working in the service and positive experiences associated with COVID were used as covariates. Data were resampled 5,000 times using a bootstrapping approach (Preacher and Hayes, 2004) to construct 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the indirect effects (those that do not include zero indicate that an indirect effect is statistically significant). The path coefficients are the beta coefficients that represent the magnitude and direction of associations between the variables included in the model.

Results

The descriptive statistics of the study variables are reported in Table 1. The average number of pandemic-related stressors experienced by participants was 4.51 (SD = 3.05; range 0–16), whilst the average number of pandemic-related positive experiences was 0.82 (SD = 0.84; range 0–3). Participants’ scores for the compassion fatigue components of burnout and secondary traumatic stress indicated that average levels were low, with the mean burnout score at 20.77 (SD = 4.90) and the mean secondary traumatic stress score at 19.09 (SD = 4.89). Participants’ mean score for compassion satisfaction was average at 41.29 (SD = 5.16). The average MHI-5 score was 76.89 (SD = 14.26) and approximately thirty-two per cent of workers scored below seventy-two, indicating difficulties with their mental health.

| . | Mean . | Standard deviation . | Range (achieved range) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pandemic stress—stressors | 4.51 | 3.05 | 0–16 (0–11) |

| Pandemic stress—positives | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0–3 (0–3) |

| Compassion satisfaction | 41.29 | 5.16 | 0–50 (28–50) |

| Burnout | 20.77 | 4.90 | 0–50 (11–32) |

| Secondary trauma | 19.09 | 4.89 | 0–50 (33–78) |

| Mental health | 76.89 | 14.26 | 0–100 (40–100) |

| . | Mean . | Standard deviation . | Range (achieved range) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pandemic stress—stressors | 4.51 | 3.05 | 0–16 (0–11) |

| Pandemic stress—positives | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0–3 (0–3) |

| Compassion satisfaction | 41.29 | 5.16 | 0–50 (28–50) |

| Burnout | 20.77 | 4.90 | 0–50 (11–32) |

| Secondary trauma | 19.09 | 4.89 | 0–50 (33–78) |

| Mental health | 76.89 | 14.26 | 0–100 (40–100) |

| . | Mean . | Standard deviation . | Range (achieved range) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pandemic stress—stressors | 4.51 | 3.05 | 0–16 (0–11) |

| Pandemic stress—positives | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0–3 (0–3) |

| Compassion satisfaction | 41.29 | 5.16 | 0–50 (28–50) |

| Burnout | 20.77 | 4.90 | 0–50 (11–32) |

| Secondary trauma | 19.09 | 4.89 | 0–50 (33–78) |

| Mental health | 76.89 | 14.26 | 0–100 (40–100) |

| . | Mean . | Standard deviation . | Range (achieved range) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pandemic stress—stressors | 4.51 | 3.05 | 0–16 (0–11) |

| Pandemic stress—positives | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0–3 (0–3) |

| Compassion satisfaction | 41.29 | 5.16 | 0–50 (28–50) |

| Burnout | 20.77 | 4.90 | 0–50 (11–32) |

| Secondary trauma | 19.09 | 4.89 | 0–50 (33–78) |

| Mental health | 76.89 | 14.26 | 0–100 (40–100) |

Correlational analyses between the study variables are presented in Table 2. A greater number of pandemic stressors were associated with significantly less compassion satisfaction, more burnout and poorer mental health. More compassion satisfaction was associated with significantly less burnout, less secondary traumatic stress and better mental health. Burnout was significantly associated with more secondary traumatic stress and poorer mental health. Finally, more years employed with the service was significantly, positively, associated with workers’ mental health.

| . | Pandemic stressors . | Pandemic positives . | Compassion satisfaction . | Burnout . | Secondary traumatic stress . | Mental health . | Years with service . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pandemic Stressors | 1 | 0.39** | −0.23* | 0.27** | 0.14 | −0.29** | −0.11 |

| Pandemic Positives | 1 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.060 | 0.14 | |

| Compassion Satisfaction | 1 | −0.61** | −0.27** | 0.29** | 0.18 | ||

| Burnout | 1 | 0.67** | −0.54** | −0.14 | |||

| Secondary Trauma | 1 | −0.47** | −0.05 | ||||

| Mental Health | 1 | 0.21* | |||||

| Years with the service | 1 |

| . | Pandemic stressors . | Pandemic positives . | Compassion satisfaction . | Burnout . | Secondary traumatic stress . | Mental health . | Years with service . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pandemic Stressors | 1 | 0.39** | −0.23* | 0.27** | 0.14 | −0.29** | −0.11 |

| Pandemic Positives | 1 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.060 | 0.14 | |

| Compassion Satisfaction | 1 | −0.61** | −0.27** | 0.29** | 0.18 | ||

| Burnout | 1 | 0.67** | −0.54** | −0.14 | |||

| Secondary Trauma | 1 | −0.47** | −0.05 | ||||

| Mental Health | 1 | 0.21* | |||||

| Years with the service | 1 |

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed).

| . | Pandemic stressors . | Pandemic positives . | Compassion satisfaction . | Burnout . | Secondary traumatic stress . | Mental health . | Years with service . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pandemic Stressors | 1 | 0.39** | −0.23* | 0.27** | 0.14 | −0.29** | −0.11 |

| Pandemic Positives | 1 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.060 | 0.14 | |

| Compassion Satisfaction | 1 | −0.61** | −0.27** | 0.29** | 0.18 | ||

| Burnout | 1 | 0.67** | −0.54** | −0.14 | |||

| Secondary Trauma | 1 | −0.47** | −0.05 | ||||

| Mental Health | 1 | 0.21* | |||||

| Years with the service | 1 |

| . | Pandemic stressors . | Pandemic positives . | Compassion satisfaction . | Burnout . | Secondary traumatic stress . | Mental health . | Years with service . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pandemic Stressors | 1 | 0.39** | −0.23* | 0.27** | 0.14 | −0.29** | −0.11 |

| Pandemic Positives | 1 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.060 | 0.14 | |

| Compassion Satisfaction | 1 | −0.61** | −0.27** | 0.29** | 0.18 | ||

| Burnout | 1 | 0.67** | −0.54** | −0.14 | |||

| Secondary Trauma | 1 | −0.47** | −0.05 | ||||

| Mental Health | 1 | 0.21* | |||||

| Years with the service | 1 |

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed).

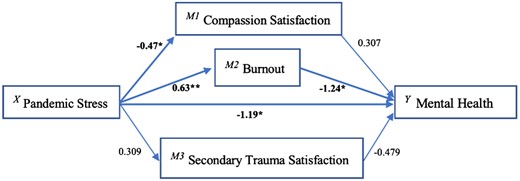

The results of mediation analyses carried out to test the effect of pandemic-related stress on workers’ mental health both directly and indirectly through the professional quality of life measures of compassion satisfaction, burnout and secondary trauma are displayed in Figure 2. A significant direct effect of pandemic-related stress on mental health was noted (b = −1.19, SE = 0.55, p < 0.05), but pandemic-related stress was also found to indirectly impact upon mental health through its effect on burnout (XM2Y = −0.78, BootSE = 0.49, 95% CI = −1.95, −0.07). Specifically, greater pandemic stress was directly associated with poorer mental health. Greater pandemic stress was also directly associated with burnout, and greater burnout was related to poorer mental health. As such, burnout partially mediated the relationship between pandemic stress and workers’ mental health. Pandemic stress was also found to negatively impact upon compassion satisfaction (b = −0.47, SE = 0.55, p < 0.05) so that more stress was associated with less satisfaction. However, the path between compassion satisfaction and mental health was not significant. Other proposed paths were not statistically significant. The overall model accounted for approximately forty-one per cent of the variance in workers’ mental health (R2 = 0.17).

Aspects of professional quality of life as mediators in the relationship between pandemic-related anxiety and care workers’ mental health.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic presented personal and professional challenges to many frontline professionals, including those involved in social care work (e.g. Abrams and Dettlaff, 2020; Banks et al., 2020). Understanding the pathways between social care workers’ pandemic experiences and their mental health is important to inform the staff-care policies and practices of providers of social work and social care services. Supporting the mental health of these workers is necessary in order for them to effectually support the vulnerable populations that they typically work with.

The present study found that greater pandemic-related stress was significantly, and directly, associated with poorer mental health. However, a significant, indirect, link between pandemic-related stress and mental health was also found through the mediating variable of professional burnout. This relationship exhibited a dose-like effect, whereby the higher the level of pandemic-related stress the greater the probability of burnout leading to poorer mental health.

Research in the United States by Gray-Stanley and Muramatsu (2011) has previously found a relationship between work-related stress and burnout, and recommended the establishment of work-based social support networks alongside provision of stress management resources. Peinado and Anderson (2020) argue that, during the pandemic, burnout was no longer exclusively associated with work-related stress, due to the unprecedented concentration of societal stressors. For social workers dealing with pandemic-related stress, they propose a variety of resources, including individual self-care practices, engagement in community volunteering and making connections with other professionals to provide mutual support. Interestingly, only one of their recommendations refers to the maintaining of a supportive workplace culture as a way of sustaining the resilience of social workers.

Whilst the suggestions for self-care as a means of mitigating the effects of stress are undoubtably helpful, it would seem that the guidance as to how agencies might both develop the means of recognising pandemic work-related stress and effective strategies to avoid worker burnout and associated poor mental health remains underdeveloped. This is not surprising as we are still in the early period of understanding the short-term effects of the pandemic, with the longer-term consequences still to be realised and researched. However, we can say with some certainty that the present study reflects the findings of the general research picture in relation to health and social care professionals in revealing associations between pandemic-related stress, increased risk of burnout and poor mental health (e.g. Froessl and Abdeen, 2021; Sumner and Kinsella, 2021).

As we have learned from the existing research, social workers, along with other professional groups, exhibit higher levels of work-related stress than other types of employees. It is also likely that the averages disguise a more complex underlying picture, whereby some individuals are carrying high stress loads associated with their own personal experiences in life (Hayes and Spratt, 2014). These individuals may, in turn, be more sensitive to the negative effects experienced as result of the pandemic. This point speaks to a limitation in the present study, in that data are cross-sectional and collected at the same point in time. Although in the conceptual model tested here we are proposing that mental health difficulties are an outcome of pandemic stress and burnout, it is also possible that workers with poorer mental health may be inclined to report greater levels of pandemic stress and burnout. As such, alternative models are possible, and we are reporting associations here instead of predictions. In addition, a further limitation relates to our inability to collect key demographic information from participants. In some services, disclosing details of age, gender or ethnicity, for example, would mean that some individuals would be readily identifiable. In protecting participants’ anonymity, this study is limited in what it can teach us about the stress, mental health or burnout experiences of different groups of workers. Finally, whilst this study did not incorporate an examination of pre-existing levels of workers’ stress in terms of quantity or sources, this is an important gap in the extant research and would benefit from investigation in future studies.

Conclusion

This study provides a snapshot of how social care workers and their service managers are faring in relation to their experience of pandemic-related stress, professional quality of life and mental health in the months after the last COVID-19 lockdowns in Ireland. It proposes that pandemic stress is directly related to both burnout and poorer mental health, and that burnout partially mediates the relationship between pandemic stress and poorer mental health. The severity and the unprecedented nature of the pandemic required that professionals who continued to provide services had to dig deep into available work and personal resources to effectually do their job supporting others. Now their psychological and work-related well-being needs to be scaffolded in order for them to continue in their roles. This study adds to a growing body of work concerned to better understand the effects of stress upon workers under pandemic conditions, with the results offering pointers to the signs that employing organisations need to be attuned to if they are to offer timely and effective supports.

Acknowledgements

The researchers are indebted to the management of the Daughters of Charity Child and Family Service, Dublin, who facilitated this research. The researchers are also grateful to the service staff who took part in the surveys. None of the research and its outcomes would have been possible without your contribution.

Funding

This project was funded by the Daughters of Charity Child and Family Service (DoCCFS), Dublin, Ireland.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.