-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sarah Carr, Georgie Hudson, Noa Amson, Idura N Hisham, Tina Coldham, Dorothy Gould, Kathryn Hodges, Angela Sweeney, Service users’ experiences of social and psychological avoidable harm in mental health social care in England: Findings of a scoping review, The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 53, Issue 3, April 2023, Pages 1303–1324, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcac209

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Avoidable harm—that is, harm to service users caused by unsafe or improper interventions, practices or services and which could have been mitigated or prevented—is embedded in social care legislation and inspections. However, the concept of avoidable harm has largely been defined by policymakers, academics, practitioners, regulators and services, with little known about service users’ experiences of avoidable harm in practice. This survivor-controlled review maps and synthesises peer-reviewed literature on service users experience of social and psychological avoidable harm in mental health social care (MHSC) in England. The review was guided by an Advisory Group of practitioners and service users. Six databases were systematically searched between January 2008 and June 2020 to identify relevant literature. Following de-duplication, 3,529 records were screened using inclusion and exclusion criteria. This led to full-text screening of eighty-four records and a final corpus of twenty-two papers. Following data extraction, thematic analysis was used to synthesise data. Six key themes were identified relating to relationships and communication, information, involvement and decision-making, poor support, fragmented systems and power-over and discriminatory cultures. Impacts on MHSC service users included stress, distress, disempowerment and deterioration in mental health. We discuss our findings and indicate future research priorities.

Introduction

Avoidable harm in mental health social care (MHSC) is recognised in legislation and policy as harm that is caused to a service user by unsafe or improper interventions, practices or services and which could have been mitigated or prevented. In England, the concept of avoidable harm is embedded in social care legislation and inspection standards. Regulation 12 of the Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2014 states, ‘The intention of this regulation is to prevent people from receiving unsafe care and treatment and prevent avoidable harm or risk of harm’ (CQC, 2014). The Care Quality Commission (CQC)—which regulates health and social care services in England through visits to monitor, inspect and rate settings—has five key inspection questions: ‘Are they safe? Are they effective? Are they caring? Are they responsive to people’s needs? Are they well-led?’ Services being ‘safe’ is defined as, ‘are you protected from abuse and avoidable harm?’ (CQC, 2018a). The interplay of best practice across the five CQC regulatory questions enables effective and person-centred safeguarding (Lawson, 2017).

The Care Act 2014 guidance on adult safeguarding states that safeguarding must ‘prevent harm and reduce the risk of abuse or neglect to adults with care and support needs’ (Department of Health & Social Care, 2022). Care and support statutory guidance on using the Care Act 2014 defines ten types of abuse with indicators: physical abuse; domestic violence or abuse; sexual abuse; psychological or emotional abuse; financial or material abuse; modern slavery; discriminatory abuse; organisational or institutional abuse. ‘Organisational or institutional abuse’, for instance, includes a failure to offer choice or promote independence, and holding abusive and disrespectful attitudes towards service users whilst ‘psychological abuse’ includes control, coercion and ‘unreasonable or unjustified withdrawal of services or support networks’ (Department of Health & Social Care, 2022).

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has published extensive guidance on improving service user experience in adult mental health settings, including discharge and transfer of care, and community care (NHS Digital, 2021). However, 2020 data on MHSC service user experience shows that around 10 per cent feel as though the way they are helped or treated undermines the way they think and feel about themselves, with 28 per cent feeling they do not have choices with their care. This figure appears to increase every year. Service user satisfaction is around 68 per cent, with those over sixty-five often more dissatisfied (NHS Digital, 2021).

Practice-based evidence suggests that MHSC service users can experience various forms of social and psychological avoidable harm (such as disempowerment and distress), including within the ten types of abuse. Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman decision reports have surfaced avoidable harm caused by, for instance, poor care planning and communication, and failure to assess needs and withdrawal of support; one report concluded that such experiences resulted in ‘distress and frustration’ for the service user (LGSC Ombudsman, 2016). Social work regulator hearing reports have identified practitioner ‘misconduct’ relating to record keeping and inadequate risk assessment as being psychologically and socially harmful for mental health service users (HCPC, 2015; Social Work England, 2020).

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no research that specifically asks service users about their experiences of social and psychological avoidable harm in MHSC. Consequently, current ways of understanding social and psychological avoidable harm and implementing strategies to minimise it may not reflect the full spectrum of ways that service users experience harms in practice. This leaves service users vulnerable to, or experiencing, harms that could be avoided if they were understood and mitigated.

We chose to explore experiences of avoidable harm in community-based MHSC settings as we believed that this had not yet been explored or defined. Additionally, a 2018 CQC report identified a deterioration in service user experience of community mental health services (2018b). It is also likely that MHSC avoidable harm in institutional settings differs from the issues concerning avoidable harm in social care in community settings. Research led by survivor researchers has suggested several aspects to avoidable harm in social care, grounded in service user experiences. Carr et al. examined mental health service user experiences of targeted violence and abuse in the context of the Care Act 2014 adult safeguarding reforms, and found that social care provision (e.g. supported housing) can be a location for abuse; community mental health staff can perpetrate harm, and trauma-informed adult safeguarding may reduce social and psychological harm (Carr et al., 2017, 2019).

Gould’s (2012) study of service users’ experiences of recovery under the 2008 Care Programme Approach, which aims to ensure coordination between health and social care agencies and practitioners, found that women of all ethnicities were dissatisfied with services’ failure to engage with alternative models of mental distress. Women as a whole and both male and female participants of African and African Caribbean heritage were especially dissatisfied with recovery services provided under the Care Programme Approach, in general, and in relation to sexism and racism.

We chose to conduct a scoping review to examine ‘areas that are emerging, to clarify key concepts and identify gaps’ (Tricco et al., 2016, p. 2). As scoping reviews include a wide range of literature in order to present a broad overview of a particular area, the quality of literature is not assessed; therefore, we did not undertake quality appraisal of included studies. We also aim to identify whether any qualitative studies specifically examine service user experiences of avoidable harm in MHSC. As we did not want to state what constitutes social and psychological harm a priori, we reviewed all relevant peer-reviewed literature that qualitatively explored service users’ experiences of MHSC.

This review is the first stage in a research programme to develop and test a service-user defined model of social and psychological harm in MHSC in England, for which it forms a basis. During later stages, MHSC service users developed the model and gave recommendations for practice and harm mitigation. The aim of this review is to assess what is known through peer-reviewed academic research and to extrapolate experiential evidence on avoidable social and psychological harm in MHSC. The review uses rigorous and systematic methods to identify, map and review research that includes service users’ experiences of any aspect of avoidable harm in any area of community-based adult MHSC in England. The research programme is survivor led and controlled, meaning it has been developed, led, and conducted by researchers who hold the identity of service user/survivor (Turner and Beresford, 2005). Our review joins a small number of reviews conducted explicitly from mental health survivor perspectives (e.g. Rose et al., 2003; Carr et al., 2017; Sweeney et al., 2019).

Methods

Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) methodological framework was used to structure and conduct the review. We modified the framework in line with Levac et al. emphasis on clarity and team-based approaches, adding a final sixth stage (Levac et al., 2010). The six stages are: (i) identifying the research question; (ii) identifying relevant studies; (iii) study selection; (iv) charting the data; (v) collating, summarising and reporting the results; (vi) and Advisory Group consultation.

The review was guided by an Advisory Group of seven people with lived experiential and/or practitioner expertise. The Group met four times over the duration of the whole study and communicated via email as needed. In particular, the Advisory Group was involved in the scoping review consultation, advising on search terms and identifying relevant literature. In keeping with the methodology, members were presented with emerging review findings for discussion and interpretation from lived experiential and/or practitioner perspectives.

Russo states that in survivor research, ‘experiential knowledge (as opposed to clinical) acquires a central role throughout the whole research process—from the design to the analysis and the interpretation of outcomes’ (Russo, 2012, p. 1). Survivor researchers centralise experiential knowledge as a valid and critical form of knowing. This survivor-generated knowledge, however, continues to have an ‘“outsider” status’ within academia (Kalathil and Jones, 2016) and is often relegated to the ‘grey zone’ of research (Straughan, 2009), with survivor researchers beginning to challenge this exclusion.

Stage 1: Identifying the research question

Our review began with the research question, ‘what is known from peer reviewed literature about mental health service user experiences of social and psychological harm in social care in England?’. This informed the development of a detailed review protocol.

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

As there are no known studies explicitly investigating our research question, our review aimed to identify any research study capturing service user experiences of, and perspectives on, MHSC to extrapolate relevant data on avoidable harm.

A search strategy was developed by the first and last authors in consultation with a social care librarian. The search was structured to reflect the key research question by combining synonyms for service user OR experience AND mental health AND social care (see Supplementary Table 1 for examples). Six health and social care databases were searched in June 2020 to identify peer-reviewed papers: PsycINFO, ASSIA, Social Care Online, Web of Science, SSCI and Social Policy and Practice. The search period was from 2008 to reflect the introduction that year of the adult social care personalisation reforms in England (HM Government, 2007). English language papers were sought as our review focuses on MHSC in England.

In addition to database searches, we contacted a range of experts and Advisory Group members for additional literature recommendations.

Stage 3: Study selection

Retrieved records were uploaded into Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016) to manage screening and selection. Following de-duplication, three reviewers (S.C., N.A. and A.S.) screened 100 records, then met to discuss findings. Disagreements and areas of uncertainty were discussed until agreement was reached. This was repeated three times, with 8.5 per cent of titles triple screened, leading to expanded inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Supplementary Table 2 for details) and high agreement between reviewers. The three reviewers then each screened one-third of the remaining records.

Inclusion criteria

Any study using any method exploring adults’ experiences of accessing, receiving, or being discharged from any community-based social care or social work service for their mental health in the public, statutory, voluntary or private sectors.

Exclusion criteria

The year 2007 or earlier; not in English; participants under fifteen (or mean age fell under sixteen); not a community setting; participants were not service users, or it was not possible to disaggregate service users’ experiences from others; service users were not using services in relation to their mental health; paper not in a peer reviewed journal and/or not an empirical paper.

The reviewers met to discuss screening results and areas of uncertainty were discussed to achieve agreement. Full texts were then retrieved and screened by (S.C. and A.S.). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were again applied, leading to a final list of included records.

Stage 4: Charting the data

Key study information was recorded on a data charting form for example, authorship, location, participants and methods. Three reviewers (A.S., I.N.H. and G.H.) extracted data, with 25 per cent double extraction.

Three reviewers then identified and extracted findings (A.S., S.C. and G.H.). To do this, we developed a working definition of avoidable harm based on service user perspectives and experiences which encompassed the acts of avoidable harm (i.e. experiences of poor practice such as discrimination) and their consequences (i.e. the impacts of the acts such as fear, powerlessness). Full papers were carefully read, and the working definition of avoidable harm applied to identify and extract relevant content.

Stage 5: Collating, summarising and reporting the results

Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) was used to develop key themes. Three authors (A.S., S.C. and G.H.) independently read all extracted findings for familiarisation. Each reviewer then generated initial codes that captured the patterns and themes occurring within and across studies relevant to the research question, moving between findings in the data charting form and the original papers to do so (see Supplementary Table 3 for an example). Twenty percent of papers were double coded. The first author (S.C.) then merged each reviewer’s codes and reflections into a comprehensive account of themes and sub-themes. The final author (A.S.) developed and revised the evolving account in consultation with the review team (S.C. and G.H.). The abstracts and findings sections of included papers were then re-checked to ensure all findings relevant to the review question were represented in the key themes. In line with Braun and Clarke, collaborative writing formed the last analytic stage.

This approach increased the validity of findings through multiple coding and data discussions, and provided a systematic and reproducible way of capturing and organising findings.

Stage 6: Consultation with expert/stakeholder advisory group

Early findings were discussed at an Advisory Group meeting to provide an additional source of knowledge and to increase the validity of data interpretation from a practice and/or lived experiential perspective. Discussions focused on literature gaps, data interpretations and connections to research, practice, legislation and policy. Whilst the conduct of consultation in scoping reviews is yet to be defined (Oravec et al., 2022), we chose a facilitated discursive approach to support collaboration and the exchange of ideas and perspectives between Advisory Group members, enabling richer data interpretations and a more comprehensive understanding of practice and policy implications.

Results

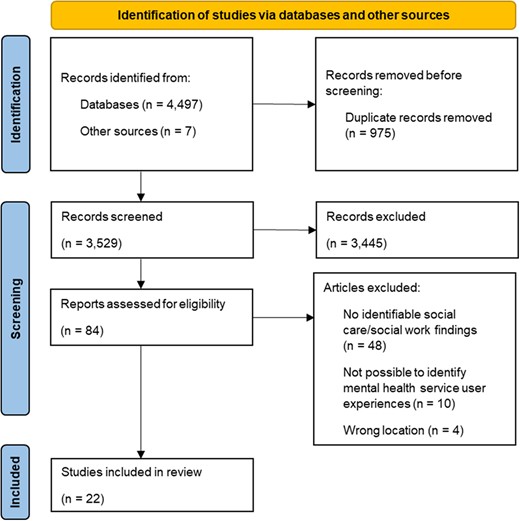

Database searches identified 4,497 records with seven additional records identified through experts. Following de-duplication, 3,529 records were screened by title and abstract. Eighty-four full-text articles were retrieved and assessed for eligibility, leading to a final pool of twenty-two included articles. Four included papers report data from the separate workstreams of two different research programmes. Figure 1 shows the review PRISMA diagram and flow of articles through the review.

A PRISMA diagram which details the number of records at each stages of the review process, from initial identification of records through to final study selection.

Overview of studies

Supplementary Table 4 provides a summary of the twenty-two included studies. Almost three-quarters employed qualitative methods (1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 16, 17, 18, 20 and 22), with three systematic (10) or literature (14 and 19) reviews. Five studies used surveys (3, 4, 5, 19 and 21), either alone or alongside qualitative (3 and 5) or review (19) methods. The two remaining studies were secondary analyses of quantitative or qualitative data (13 and 15).

Thirteen studies described some service user involvement in conducting the research (1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 20), typically through an advisory or focus group comprising, at least partially, of service users (1, 3, 6, 8, 9, 12, 15, 16 and 20). Six studies reported employing mental health service users/survivors as researchers (3, 4, 7, 9, 12 and 18). One study collaborated with a service user-run mental health charity throughout (17). Only three studies (3, 9 and 12) employed service users as researchers ‘and’ sought advice from service user focus or advisory groups. Nine studies did not provide any relevant or clear information (2, 5, 10, 11, 13, 14, 19, 21 and 22).

Almost half of the twenty-two studies recruited from community mental health teams (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21 and 22). Remaining studies were recruited from various settings, including support groups (17), local authorities or local voluntary sector organisations (6), specialist learning disability services (7), NHS mental health care providers (9) and supported housing/homeless hostels (11).

Eight studies reported a near equal split of male/female service user participants (1, 7, 8, 15, 17, 19, 20 and 22). Most remaining studies were majority female, except one majority male study (11). In two studies, a small number of participants identified as transgender or non-binary (4 and 12). Of the seven studies reporting participants’ ethnicity (2, 4, 9, 12, 16, 17 and 21), all reported predominantly White participants except for one (16) which had an even split between White participants and those from racialised groups. In two studies (7 and 8) participants were people with learning disabilities. No studies reported whether participants had physical or sensory disabilities.

Nearly half of the studies focused on perspectives and experiences of mental health services with a social care or social work component (3, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 17, 18, 22). The remaining studies investigated experiences of care plans (1, 2, 21), social work interventions (9, 13, 19), discrimination (4), personal budgets (6, 15, 20) and violence and abuse (12, 16).

Studies focused on various aspects of MHSC including assessment and care planning (1, 2, 3, 11 and 21); personal budgets and self-directed support (6, 15, 18 and 20); mental health social work with parents (4, 9 and 13); relationship quality and communication with social workers and social care workers (17, 19 and 22); learning disability MHSC (7 and 8); and continuity of care (5 and 14). There were single studies on supported accommodation (10), adult safeguarding (12) and domestic violence and social services for people experiencing mental distress (16).

Ten studies explicitly identified various forms of social and psychological harm. Psychological and emotional harm in the form of stress, fear, distress, disempowerment and discrimination was evidenced for parents (particularly mothers) with mental distress using social work services (4 and 9). Experiences of discrimination, stress, fear and ‘upset’ were reported for people with learning disabilities using MHSC (7 and 8). Two studies on personal budgets and self-directed support suggested that psychological harm can occur when mental health service users lack control and feel stressed (6 and 15). Stress and distress were also reported in a study of violence and abuse in the context of adult safeguarding (12). Similarly, one study showed that psychological harm characterised by stress and disempowerment can result from poor relationships and communication with staff (17). Studies also showed that psychological and emotional harm can happen when victims of domestic violence with mental distress feel fear and shame (16) and when those in supported accommodation feel disempowerment, stress, loss and loneliness (10). Interestingly, nine out of these ten studies involved service users either as advisors or researchers.

Findings

Findings were organised into six key themes that captured the dataset on service user experiences of avoidable harm in MHSC.

Poor relationships and communication with practitioners

Negative experiences of encounters and relationships with practitioners resulted in some service users experiencing stress, distress and disempowerment. Poor communication was often a significant cause of harmful relational practices. One study found that poor communication arises when practitioners inflexibly adhere to formal assessment processes, instead of having conversations with service users (Brooks et al., 2018). Another study highlighted how ‘distant’ or disengaged relationships with practitioners can prevent communication about risk and safety, often leaving service users to manage this alone (Coffey et al., 2017). One study found that service users felt practitioners were not interested in, nor took the time to get to know, them (Kroese et al., 2013).

Practitioners often made decisions about care planning and support without listening to or discussing this with service users, or overrode service users’ decisions, causing people to feel undermined, disempowered and/or distressed (O’Brien and Rose, 2010; Jeffery et al., 2013; Norrie et al., 2014; Hamilton et al., 2016; Simpson et al., 2016). Some service users fear complaining, challenging decisions or negotiating personal budgets (O’Brien and Rose, 2010; Hamilton et al., 2016; Krotofil et al., 2018). One study highlighted that service users need to be confident and assertive to negotiate personal budgets where practitioners view the money as a ‘gift’; this was disempowering especially where service users felt they were ‘begging’ (Hamilton et al., 2016).

A study into service user satisfaction with practitioners in community mental health teams found higher satisfaction with community mental health nurses than mental health social workers (Boland et al., 2021). A further study suggested that mental health service users may see new social workers as a potential threat due to fear of hospitalisation (Bacha et al., 2020). Practitioners who breached confidentiality risked undermining service user confidence in them (Kroese et al., 2013).

Three studies reported that practitioners who were judgemental, stigmatising or discriminatory towards parents (particularly mothers) with mental health problems could cause significant avoidable harm including distress, fear and disempowerment (Jeffery et al., 2013; Henderson et al., 2015; Lever Taylor et al., 2019).

Information, involvement and decision-making

Several studies investigated care planning, including assessment and risk assessment, and found that service users can experience a disempowering and stressful lack of involvement or control (Cameron et al., 2014; Cornes et al., 2014; Larsen et al., 2015; Simpson et al., 2016; Coffey et al., 2017; Brooks et al., 2018; Krotofil et al., 2018). In some studies, service users were unaware of their care plans or not given copies, often resulting in disempowerment or needs not being met (Cameron et al., 2014; Cornes et al., 2014; Hamilton et al., 2016; Coffey et al., 2017; Brooks et al., 2018; Krotofil et al., 2018). Further acts of avoidable harm included practitioners making decisions about care planning and support; defining vulnerability, risk and harm without consulting service users; and not routinely discussing risk and safety in assessments and care planning (O’Brien and Rose, 2010; Cameron et al., 2014; Simpson et al., 2016; Brooks et al., 2018; Krotofil et al., 2018; Carr et al., 2019). Two studies suggested this could undermine recovery-focused care (Simpson et al., 2016; Coffey et al., 2017). Some service users felt they could not influence or challenge professional decisions or were not listened to, particularly people with learning disabilities and mental health difficulties (O’Brien and Rose, 2010; Kroese et al., 2013; Krotofil et al., 2018).

Service users with care plans and in receipt of personal budgets often lacked sufficient information to make decisions (Norrie et al., 2014; Hamilton et al., 2016). Limited understanding of how personal budgets worked and what they could be used for impacted service users’ choice and control. This was exacerbated by a lack of user-led organisations, advocacy and support brokerage.

Lack of support or support that fails to meet needs

A lack of service user involvement in care planning and limited decision-making power can result in social care support failing to meet needs, including for those in supported accommodation or experiencing homelessness (Cornes et al., 2014; Krotofil et al., 2018). Inappropriate, inconsistent, disrupted or poorly timed support could cause deteriorating mental health, increased exposure to external harms, disrupted family life and fears around disclosing needs (Rose et al., 2003; Cornes et al., 2014; Boland et al., 2021; Lever Taylor et al., 2019; Carr et al., 2019a; Bacha et al., 2020).

Avoidable harm was at times specific to particular groups. Spirituality and religious beliefs, for instance, were not always accurately recorded or included in assessments and care planning, meaning associated needs were not met (Walsh et al., 2013). People with learning disabilities and mental distress who did not get support in time said they felt ‘let down’ (O’Brien and Rose, 2010). A lack of social work input and support in early pregnancy sometimes caused longer-term negative effects (Lever Taylor et al., 2019). A disproportionate focus on risk could mean that the social care support needs of parents with mental distress were not met, including support to keep children at home (Jeffery et al., 2013; Lever Taylor et al., 2019).

A lack of funding and staffing sometimes caused reductions in care and support (Simpson et al., 2016; Brooks et al., 2018). Barriers and burdens of care planning processes, lengthy waits and non-transparent decision-making, particularly with social care funding and personal budgets, delayed service users getting the right social care support and prevented them from exercising control (Norrie et al., 2014; Hitchen et al., 2015; Larsen et al., 2015; Hamilton et al., 2016). Delayed or inadequate adult safeguarding responses can mean that people experiencing harm are left without proper protection and support (Carr et al., 2019). Other consequences of support that fails to meet needs included disengagement (Carr et al., 2019; Lever Taylor et al., 2019); reduced likelihood of reporting and increased exposure to abuse/domestic violence (Rose et al., 2003; Carr et al., 2019); and worsening mental distress (Henderson et al., 2015; Hitchen et al., 2015; Hamilton et al., 2016; Lever Taylor et al., 2019).

Inflexible, bureaucratic systems

Organisational bureaucratic systems and administrative requirements can cause avoidable harm and stress, distress and deteriorating mental health. This was particularly apparent in relation to complex, bureaucratic and burdensome assessment and care planning processes and personal budget management (Norrie et al., 2014; Larsen et al., 2015; Hamilton et al., 2016; Simpson et al., 2016; Bacha et al., 2020). Four studies indicated that local authority bureaucracy and administrative burdens caused some personal budget holders considerable and sometimes excessive stress (Norrie et al., 2014; Larsen et al., 2015; Hamilton et al., 2016; Simpson et al., 2016). In one study, personal budget recipients felt overwhelmed by paperwork and reliant on family for administrative support (Hamilton et al., 2016). Eligibility criteria could mean that service users were offered personal budgets when unwell and less able to manage them alone without sufficient support, again resulting in stress, distress and deteriorating mental health (Hitchen et al., 2015; Hamilton et al., 2016).

Fragmented services and discontinuity

A lack of joint working and integration between mental health and social care services sometimes resulted in fragmented, incoherent care pathways and stressful and distressing adult safeguarding responses (Carr et al., 2019; Flynn et al., 2019). Poor integration and lack of communication between agencies and within community mental health teams can cause avoidable harm (Cameron et al., 2014; Cornes et al., 2014; Simpson et al., 2016). Research into adult safeguarding for those with mental health problems described a situation where agencies and practitioners ‘pass the buck’ causing risky and distressing delays to or lack of responses (Carr et al., 2019).

A literature review of service users’ experiences of supported accommodation found that an emphasis to ‘move on’ was disruptive and distressing (Krotofil et al., 2018). One study suggested that people with ‘complex needs’ can experience difficulties in being transferred to safe and secure accommodation, with social vulnerability influencing experiences of continuity (Jones et al., 2009). In three studies, lack of staff stability and continuity was associated with the stress of disrupted support, loss of trust and feeling ‘let down’ (O’Brien and Rose, 2010; Cornes et al., 2014; Coffey et al., 2017).

‘Power over’ and discriminatory organisational cultures

Wider organisational cultures, systems and management practices can create environments where service users experience psychological, emotional or social harm, with power and control apparent in three studies (O’Brien and Rose, 2010; Simpson et al., 2016; Coffey et al., 2017). Two studies reported that systems can feel impersonal and service users can feel ‘lost’ or like ‘objects’ (Carr et al., 2019; Bacha et al., 2020).

Organisational cultures and systems characterised by ‘power over’ approaches with little service user control could negatively affect service users’ experiences of frontline practice, resulting in stress and distress. Organisational cultures impacted professional attitudes, risk conceptualisation and the extent to which service users could communicate honestly with frontline practitioners and exercise choice (Rose et al., 2003; O’Brien and Rose, 2010; Simpson et al., 2016; Coffey et al., 2017; Lever Taylor et al., 2019; Bacha et al., 2020).

Three studies suggested that where social care services operate in the context of the Mental Health Act 1983 and 2007, service users can fear or experience coercion and control. One study cited fear of hospitalisation as impacting trust and communication with social work practitioners (Bacha et al., 2020); another highlighted negative effects on choice and control in care planning (Simpson et al., 2016); whilst a third reported service user disempowerment and frustration when supported accommodation environments were overly restrictive (Krotofil et al., 2018). In a further study, crisis-oriented mental health services had an impact on the provision of preventative social care support in the community, potentially causing deteriorating mental health (Jones et al., 2009).

Studies of parents and those with learning disabilities surfaced the harmful effects of the cultural conceptualisation of people experiencing mental distress as inherently risky or lacking capacity or competency, including discrimination, disempowerment, loss of independence and distress (O’Brien and Rose, 2010; Jeffery et al., 2013; Kroese et al., 2013; Lever Taylor et al., 2019). Three studies suggested that systemic discrimination against parents experiencing mental distress—where they were automatically seen as ‘unfit’ parents and a risk to their children—resulted in psychological and emotional harm, disempowerment, deteriorating mental health and damage to family life (Jeffery et al., 2013; Henderson et al., 2015; Lever Taylor et al., 2019). Two studies highlighted how organisational cultures and management practices can work against recovery (Simpson et al., 2016; Coffey et al., 2017).

Discussion

Our scoping review identified, mapped and synthesised literature on service users’ experiences of MHSC in England in order to understand the ways in which avoidable harm is experienced in practice. We found no direct research on this topic, with twenty-two studies reporting service users’ broader experiences of MHSC. From this, we extrapolated findings on avoidable harm, such as poor relationships with practitioners and discriminatory practice, and its consequences, such as stress and disempowerment.

In mapping the field, we found that most studies are qualitative, with nearly half having no form of service user involvement in their research. Just one study was led by people who identify as mental health service users (i.e. first or last author was described as such). Multiple studies were set in community mental health teams and explored views and experiences of mental health services with a social work or social care component. In describing service user experiences, around half of the studies also described the negative consequences of avoidable harm such as distress and disempowerment. Of the ten studies that explicitly identified forms of social and psychological avoidable harm, nine had involved service users either as advisors or researchers. Whilst we are hesitant to draw conclusions from this, it seems possible that research that does not involve service users and/or is led by practitioner researchers is less likely to investigate specific harms.

Our major finding is that service users can experience a wide range of avoidable social and psychological harms at relational, systemic and cultural levels related to poor relationships and communication; poor information and involvement; a lack of or inadequate support; inflexible and bureaucratic systems; fragmented services and discontinuity; and ‘power over’ and discriminatory cultures. These findings can be mapped to some of the types of abuse described in the statutory guidance on using the Care Act 2014, most notably organisational or institutional abuse, psychological and emotional abuse and discriminatory abuse (Department of Health & Social Care, 2022).

The Care Act 2014 guidance defines organisational and institutional abuse as including a failure to offer choices or consider cultural, religious or ethnic needs, and insufficient staff or high staff turnover resulting in poor quality support. A study on what service users value in mental health social work concluded that ‘service users value support that is reliable and continuous, and that … interruptions … are likely to badly undermine the value of social work to the end-user’ (Wilberforce et al., 2020, p. 1340). The problems outlined in the Care Act guidance and factors that undermine what service users value in mental health social work were apparent in our review and contributed to some people experiencing a lack of or inadequate support, often with significant consequences. This finding cannot be disentangled from a social care system that is under immense funding pressure (Thorlby et al., 2018) and historically struggles to recruit and retain mental health social workers (Huxley et al., 2005).

Psychological and emotional abuse within the Care Act 2014 guidance includes control and coercion. Mental Health Act 1983 and 2007 assessments by social workers and psychiatrists resulting in service users reporting psychological harm have been documented (The Mental Health Act Commission, 2009). Our review found that mental health social work that operated within the context of the Mental Health Act 1983 and 2007 could cause service users to fear or experience coercion and control, negatively impacting trust and communication with practitioners. This echoes findings by Sweeney et al. (2015) that either the possibility or experience of detention without consent had multiple consequences for service users, including damaged therapeutic relationships and poor engagement with services.

Discriminatory abuse within the Care Act 2014 guidance includes providing unequal treatment or substandard services to people with protected characteristics and failing to respect privacy. We found that parents with mental health problems experienced systemic discrimination, often being seen as unfit to parent because of their mental distress with impacts including disempowerment, deteriorating mental health and damaged family life (Jeffery et al., 2013; Henderson et al., 2015; Lever Taylor et al., 2019). Similarly, people with learning difficulties were at times seen as inherently incapable. However, our findings are limited by a lack of research into the MHSC experiences of those with protected characteristics.

Within our review, particular harms run, thread-like, across relational, systemic and cultural levels. This can be conceived from an ‘ecological’ perspective (McLeroy et al., 1988) which assumes that ‘multiple levels of influence exist but also that these levels are interactive and reinforcing’ (Golden and Earp, 2012, p. 364). Our review shows that policy, organisational, cultural, administrative and relational factors can function together, causing harm at individual service user levels. This implies that ultimately whole system change could address the issues with avoidable harm identified here and that multiple harms should be addressed at different levels simultaneously.

This has implications for frontline practice. For instance, lack of control and disempowerment is enacted within relationships by frontline practitioners but also embedded in systems and organisations through legislated powers of compulsion under the Mental Health Act 1983 and 2007, and restrictive or discriminatory cultures. According to the British Association of Social Work (BASW) Code of Ethics (BASW, 2021), practice that is experienced as distressing, disempowering or discriminatory is unethical. However, the organisational cultures and bureaucratic systems in which social workers operate may also be unethical and harmful, thereby compromising these frontline relationships. BASW expects ‘employers to have in place systems and approaches to ensure social workers can comply with the Code of Ethics and other requirements to deliver safe and effective practice’ (BASW, 2021, p. 9). Our findings suggest that negative systems and cultures, particularly in the context of funding cuts, may also be harmful to social care practitioners if they experience ‘continual inability to implement actions that [they] consider morally appropriate’ (Mänttäri-van der Kuip, 2016, p. 86). Such conditions can result in practitioner ‘moral distress’, with research showing that ‘perceived resource insufficiencies are strongly associated with experiences of moral distress among frontline social workers’ (Mänttäri-van der Kuip, 2016, p. 86).

It is important to note that many studies included in this review also described good practice, more so for some areas and populations than others (e.g. we found particular abuses for parents with mental distress and people with learning difficulties). We have not aimed to explore that good practice, nor to quantify the avoidable harms identified: a future review could aim to understand what ‘good’ looks like from service user and survivor perspectives. Instead, we have begun exploring what is known from the literature about the ways in which avoidable harm is experienced and how its impacts are experienced by MHSC service users.

We also note that our findings do not comprehensively explore the full spectrum of avoidable harms that service users experience. Our review reveals important knowledge gaps, for instance, whilst we identified discriminatory cultures in relation to parents and people with learning difficulties, apart from one user-led study (Carr et al., 2019), the extant body of research does not investigate the harmful experiences, including of discrimination, of others with protected characteristics and/or marginalised identities or consider intersectionalities. Additional research, ideally led by or in collaboration with people with direct experience, is urgently needed. Further, the studies included in this review typically did not set out to explore the impacts of avoidable harm. Given the range of avoidable harms identified, and early indications about their impacts, future research that explicitly investigates the impacts of avoidable harm on service users seems warranted.

Strengths and limitations

We employed a team-based approach within a rigorous methodological framework (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005), incorporating clarifications and modifications by Levac et al. (2010). The review was informed by an Advisory Group of people with experiences of using, delivering and overseeing services. Members offered extremely valuable advice and insights but because meetings took place during the COVID-19 pandemic they were conducted on Zoom rather than in person and this may have restricted the participation of some members.

Further limitations include that, in line with scoping review methodology, we have not critically appraised the quality of the evidence base (Munn et al., 2018). The review is only applicable to England because of the unique nature of social care systems within individual nations. In addition, the review only focuses on community mental health services. As there is no direct research, avoidable harms were extrapolated from broader research on service users’ experiences of varying aspects of MHSC in England. Therefore, the range of harms identified is constrained by the topics and populations that have been investigated. We did not set out to investigate the frequency of avoidable harms, nor the proportion of interventions that result in an avoidable harm, limiting what can be understood from our review. Additionally, our focus was on the avoidable harm caused directly by MHSC, rather than harm from other causes that MHSC services failed to prevent. However, scoping the literature has enabled us to map and identify research gaps, indicating where further research is needed. Whilst this study did not set out to understand how to minimise such harms, nor to investigate positive or optimum MHSC practice, these are clearly important topics for future research. Furthermore, we found studies that explicitly identified harms, were far more likely to have involved service users, highlighting the importance of service user involvement in future research.

Conclusion

Our scoping review found that service users experience a range of social and psychological avoidable harms when in contact with MHSC services which can cause significant stress, distress, disempowerment, deteriorating mental health, poor therapeutic relationships, and a fear of using services. The harms caused by contact with MHSC arise through a combination of relational, systemic and cultural factors. However, there is no research that explicitly investigates mental health service users’ experience of, or perspective on, the services that they receive, and almost no research has explored the experiences of people from marginalised communities. Future research should explicitly investigate the full spectrum of avoidable harms that service users experience through their use of MHSC and the impacts and mitigators of such harms, as well as ensuring a focus on intersectional experiences.

Acknowledgements

A.S. would like to acknowledge the support of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

The authors would like to extend deepest thank to the study’s Advisory Group and Jane Lawson for their vital input and support throughout the study. Additional thanks to Emma Green, Librarian, Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham for her thoughtful support in constructing and conducting the searches. Any errors are, of course, the authors.

Funding

This paper reports on independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Social Care Research (NIHR SSCR, grant number C969/CM/UBCN-P137). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR SSCR, the National Health Service, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.