-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mark Wilberforce, Michele Abendstern, Saqba Batool, Jennifer Boland, David Challis, John Christian, Jane Hughes, Phil Kinder, Paul Lake-Jones, Manoj Mistry, Rosa Pitts, Doreen Roberts, What Do Service Users Want from Mental Health Social Work? A Best–Worst Scaling Analysis, The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 50, Issue 5, July 2020, Pages 1324–1344, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz133

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Despite being a profession dedicated to the empowerment of service users, empirical study of mental health social work appears dominated by the perspectives of social workers themselves. What service users value is less often reported. This study, authored by a mix of academics and service users/carers, reports a Best–Worst Scaling analysis of ten social worker ‘qualities’, representing both those highly specialist to social work and those generic to other mental health professionals. Fieldwork was undertaken during 2018 with 144 working-age service users, living at home, in five regions of England. Of specialist social work qualities, service users rated ‘[the social worker] thinks about my whole life, not just my illness’ particularly highly, indicating that person-centred approaches drawing on the social model of mental health are crucial to defining social work. However, service users did not value help accessing other community resources, particularly those who had spent the longest time within mental health services. Continuity of care was the most highly valued of all, although this is arguably a system-level feature of support. The research can assist the profession to promote the added value of their work, focusing on their expertise in person-centred care and the social model of mental health.

Introduction

Social work’s place within mental health services has been long debated, and a critical consensus is that social work’s unique and specialist role lacks clear articulation (Social Work Task Force, 2009). International literature variously points to the challenge of role blurring, particularly in multidisciplinary environments where the confluence of different professional identities (and the relative dominance of the medical model) can lead to stereotyping and misuse of social work skills (Bourgeault and Mulvale, 2006; Maddock, 2015). It is argued that mental health social work has been gradually eroded by a ‘creeping genericism’ across some professional groups (Brown et al., 2000, p. 426), or else has contributed to a culture clash where professional territory is contested (Rees et al., 2004). Where mental health social workers perceive a conflict between their values and those of the wider team, or else feel their role is ambiguous, there are well established and deleterious consequences for job satisfaction (Acker, 2004).

In England, an ongoing debate centres on whether specialist social work is best undertaken as part of integrated care teams, with concern that its role may be diminished within broader care coordinator duties that are ‘dominated by NHS performance drivers’ (Allen et al., 2016, p. 12). Successive legislative changes over recent decades have further diluted social work’s unique contribution (Rapaport, 2005). These include Mental Health Act reforms in which statutory duties that were previously the preserve of social work were opened to a wider range of health and allied health professions, contributing to a ‘reduced status’ compared to other disciplines (Bailey and Liyanage, 2012). Moreover, a widely reported finding is that the managerialist approaches to risk have further eroded the autonomy and professional judgement of social workers relative to other professions (Wilberforce et al., 2014). Although more optimistic accounts exist (Evans, 2013), and social work undoubtedly continues to play a leadership role amongst Approved Mental Health Practitioners (AMHPs), the dominant narrative is of a professional specialism that is marginalised and misunderstood relative to other disciplines (All Party Parliamentary Group on Social Work, 2013).

Even where genericism has been resisted, the unique contribution of social work has nevertheless been described as ‘invisible’, working in liminal spaces left unoccupied by other professional groups. In Morriss's (2017) study, respondents felt best able to describe social work’s specialist role only in their interactions with other mental health social workers, which she linked to Pithouse's (1998, p. 5) observation that only social workers themselves can ‘appreciate what it means to do social work’, through their common frame of reference. Little wonder, therefore, that extant literature comprises so many studies examining social workers’ experiences within the profession (Jacobs et al., 2013). Common subjects of inquiry include social work’s role within mental health legislation; social worker job satisfaction, autonomy and stress; social work theory and models of recovery; role blurring and multidisciplinary working as part of integrated approaches; social work education, supervision and culture; the role of social work vis-à-vis the state and government policy; and anti-oppressive practices (Moriarty et al., 2015).

Against this background, the social work profession across the UK has taken significant steps to define its unique role in mental health. In England, one contribution of the short-lived College of Social Work was to present a framework for mental health social work, and an attempt to cross-reference this to the wider Professional Competency Framework that guides the profession as a whole (Allen, 2014). New curricula dedicated to mental health social work training, such as the Think Ahead programme, have perhaps bolstered its sense of specialism. In Northern Ireland, recent efforts to clarify the contribution of mental health social work were founded on widespread consultation (Office of Social Services, 2019). However, whether these efforts have led to consolidation of understanding around specialist social work roles in mental health is unclear. For now, crystallising and protecting the distinct mental health social work role remain problematic (Vicary and Bailey, 2018; Morriss, 2017)

Curiously, for a profession dedicated to empowering service users and carers, comparatively few empirical studies have investigated their perspectives of social work (Kam, 2019). In part, this gap may reflect the difficulties that service users have had in establishing a voice in academic circles (Beresford, 2013). Research with users has tended to examine views of their experiences of mental health need or their interactions with services, but relatively few studies have examined what service users think of mental health social work per se. The limited range of service user perspectives from research may also be echoed in practice, since critical reflection about the views of mental health service users is not a routine activity, either by custom or regulatory requirement (Allen et al., 2016).

Yet it may be that the views of service users can help to discern and promote the uniqueness of social work. Nathan and Webber (2010) argue that making a convincing case for mental health social work demands ‘putting service users at the centre of the profession’s practice’, since ‘no other professional grouping can claim a core defining principle based on giving service users a voice’ (p. 23). Existing evidence, as limited as it is, provides some initial insights. Evidence reviews (Penhale and Young, 2015; Boland et al., 2019), drawing mostly on qualitative evidence, found many personal and values-based qualities crucial to social work across the profession, including honesty, integrity, warmth, openness, courtesy, positivity, reliability and compassion. Many have referenced qualities akin to friendship, or at least a reciprocal relationship with social workers offering a sense of equality between people of equal worth (Penhale and Young, 2015). Specific skills recognised and valued by service users include the capacity for social work to help them build empowering social relationships, and the attention to wider support needs beyond the relief of psychiatric symptoms (Laugharne et al., 2012). Other studies have noted the importance of advocacy and providing important information around rights, entitlements and service availability (Penhale and Young, 2015). Although the evidence is limited, there is nevertheless no shortage of social work components in high demand. However, such expansive lists of important social work characteristics create another problem, since there is no basis on which to prioritise or promote any particular attribute in defining the profession.

Three notable gaps in the knowledge base remain. First, it is unclear whether service users value some attributes of social work more highly than others. Knowing this would allow such features to be given greater prominence in professional development, and in raising the status of the profession by emphasis on its unique contribution to service user support. Secondly, a valuable step towards articulating social work’s unique place in mental health support would be to answer whether ‘specialist’ social work attributes were valued more highly than more ‘generic’ qualities. Finally, there is little evidence to ascertain whether preferences for different social work attributes vary by service user characteristic. Understanding this preference heterogeneity would help social workers to understand how different user groupings might value different aspects of their role. In helping to meeting these gaps, the research presented in this article aimed to evaluate the strength of service user preferences for different social worker qualities.

Method

The research used a Best–Worst Scaling (BWS) approach to estimate service users’ relative valuation of different attributes in a hypothetical social worker. An ‘attribute’ is defined as a discrete and definable aspect or characteristic of social worker support, as perceived by service users. A BWS is part of a class of research procedures (discrete choice methods) developed in the field of economics to estimate the strength of preferences for different service features. This is achieved by asking participants to select their most and least preferred options from hypothetical scenarios presented to them. A BWS is preferred to other methods (e.g. simple ratings using Likert scales) since it is argued that asking people to choose between potentially valuable sets of service attributes reveals their true preferences, and overcomes the problem of ‘halo effects’ (a cognitive bias in research in which all service attributes are presumed equally positive, or negative, without distinction between them).

The research was coproduced. The full research team comprised academics together with six people with expertise by experience of being supported by social workers with their mental health needs, and/or as a carer for a family member. Their preference was to be titled as ‘lay members’ of the research team, to mirror a term they were familiar with in other roles they played. Six stages in the BWS design are described as follows.

Stage 1: identifying candidate social worker ‘attributes’

In the first stage, the lay members of the research team met to discuss what they perceived as being the contribution of social work to their mental health support, with a researcher acting as scribe. This discussion was informed by the research team’s prior literature review on social work in mental health (Boland et al., 2019). The group arrived at forty-six ‘statements’ describing what they valued from social workers, organised into three themes: (i) social worker values; (ii) skills, knowledge and experience; and (iii) activities and tasks.

Stage 2: expert rating

These forty-six statements were then presented to an expert social work group through an online survey. The expert rating was designed to establish whether each statement represented an attribute that was unique to social work, or one that was generic to other professions. Specifically, each participant was asked to rate how important each statement was in defining the ‘distinct contribution’ of social work in mental health services. The survey defined ‘distinct contribution’ as meaning what social workers add to services that would not be delivered to the same extent or standard in their absence.

Experts were all either recently or currently practising mental health social workers or social work researchers/academics who had published in mental health field. Thirty-one responses were obtained from fifty-six invited experts.

Stage 3: shortlisting panel

Concurrently with Stage 2, a new panel of service users and carers was convened to discuss and prioritise the forty-six statements towards a shortlist. Facilitated by lay members of the research team, the panel divided into three groups to discuss one of the three categories (from Stage 1 above) of statements. Each group was asked to identify the three statements of most importance to their perceptions of mental health support. The outcome was a list of nine statements. When combined with data from Stage 2, it was evident that this shortlist included a blend of both ‘unique’ and ‘generic’ attributes (as intended).

Stage 4: defining the final attribute list

The lay members of the research team met to review the final nine attributes and to add definitions. These definitions would be presented to BWS participants so that the attributes were interpreted consistently. The definitions were initially drafted by the academic members of the research team, but during the meeting these were edited until the lay members were satisfied with what they represented. During the discussion, the researchers asked if there was any attribute notably absent from the list. Reflecting on the comments heard during the shortlisting panel, the lay members of the research team requested an additional attribute reflecting ‘compassion’. This was not part of the original set of forty-six attributes, but the lay members felt that a study of what service users sought from their social work support should include this crucial component. It was therefore decided to extend the attribute list to ten.

Table 1 summarises the final list of attributes and their definitions. The result from the online expert rating exercise corresponding to each attribute (in descending order of how unique the attribute was in defining social work’s contribution to mental health support) is also presented. However, note that the wording of each attribute changed at Stage 4 (after the online expert rating had been completed), therefore this is only illustrative.

Ten social work attributes and their importance in defining social work’s distinct contribution to mental health care

| Attribute: ‘The social worker …’ . | Definition . | Rating of ‘uniqueness to social work’, n (%) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High . | Medium . | Low . | ||

| thinks about my whole life, not just my illness | The social worker is interested in all the things that are important to me and my life, not just the symptoms of my mental health problem. | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | – |

| protects my rights and entitlements | The social worker makes sure that I am aware of my rights and that they are protected. This means making sure that I am fairly treated, and that I am receiving any benefits that I am entitled to. | 28 (90.3) | 3 (9.7) | – |

| is non-judgemental | The social worker does not criticise me or my choices. They do not try to tell me how to live my life based on their own judgements or those of wider society. They help me to live according to my own values. | 27 (87.1) | 4 (12.9) | – |

| arranges access to other services | The social worker works closely with others to get the help I need. They might make referrals to other NHS or social care services, or (with my permission) talk with colleges, employers, voluntary services and others. | 26 (83.9) | 5 (16.1) | – |

| looks carefully for signs of abuse and neglect | The social worker is experienced in identifying different forms of abuse and neglect (physical, verbal, emotional, financial and sexual). | 24 (80.0) | 4 (12.9) | 2 (6.5) |

| understands why people become vulnerable | The social worker is experienced in helping people to avoid being exploited or discriminated against. This may be because of mental health, disability, ethnicity, poverty or other reasons. | 23 (74.2) | 8 (25.8) | – |

| suggests different ways of helping me, and does not concentrate on medication alone | The social worker will consider, and inform me about, different options that might be helpful. These could include attending social and leisure activities, helping with life skills, education, work and talking therapies. | 20 (64.5) | 9 (29.0) | 2 (6.4) |

| is a reliable and continuous point of contact | The social worker can be relied upon to do what they say they will do. It will be the same social worker I see each time. | 17 (54.8) | 13 (41.9) | 1 (3.2) |

| understands how people’s difficulties can vary from time-to-time | The social worker knows that how someone feels one day can be quite different to another day. By understanding this, they can see when I need more support. | 13 (41.9) | 15 (48.4) | 3 (9.7) |

| is compassionate | The social worker is caring and considerate. They show empathy and understanding of how my past and current problems affect me. | n/a | ||

| Attribute: ‘The social worker …’ . | Definition . | Rating of ‘uniqueness to social work’, n (%) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High . | Medium . | Low . | ||

| thinks about my whole life, not just my illness | The social worker is interested in all the things that are important to me and my life, not just the symptoms of my mental health problem. | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | – |

| protects my rights and entitlements | The social worker makes sure that I am aware of my rights and that they are protected. This means making sure that I am fairly treated, and that I am receiving any benefits that I am entitled to. | 28 (90.3) | 3 (9.7) | – |

| is non-judgemental | The social worker does not criticise me or my choices. They do not try to tell me how to live my life based on their own judgements or those of wider society. They help me to live according to my own values. | 27 (87.1) | 4 (12.9) | – |

| arranges access to other services | The social worker works closely with others to get the help I need. They might make referrals to other NHS or social care services, or (with my permission) talk with colleges, employers, voluntary services and others. | 26 (83.9) | 5 (16.1) | – |

| looks carefully for signs of abuse and neglect | The social worker is experienced in identifying different forms of abuse and neglect (physical, verbal, emotional, financial and sexual). | 24 (80.0) | 4 (12.9) | 2 (6.5) |

| understands why people become vulnerable | The social worker is experienced in helping people to avoid being exploited or discriminated against. This may be because of mental health, disability, ethnicity, poverty or other reasons. | 23 (74.2) | 8 (25.8) | – |

| suggests different ways of helping me, and does not concentrate on medication alone | The social worker will consider, and inform me about, different options that might be helpful. These could include attending social and leisure activities, helping with life skills, education, work and talking therapies. | 20 (64.5) | 9 (29.0) | 2 (6.4) |

| is a reliable and continuous point of contact | The social worker can be relied upon to do what they say they will do. It will be the same social worker I see each time. | 17 (54.8) | 13 (41.9) | 1 (3.2) |

| understands how people’s difficulties can vary from time-to-time | The social worker knows that how someone feels one day can be quite different to another day. By understanding this, they can see when I need more support. | 13 (41.9) | 15 (48.4) | 3 (9.7) |

| is compassionate | The social worker is caring and considerate. They show empathy and understanding of how my past and current problems affect me. | n/a | ||

n/a, not applicable.

Ten social work attributes and their importance in defining social work’s distinct contribution to mental health care

| Attribute: ‘The social worker …’ . | Definition . | Rating of ‘uniqueness to social work’, n (%) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High . | Medium . | Low . | ||

| thinks about my whole life, not just my illness | The social worker is interested in all the things that are important to me and my life, not just the symptoms of my mental health problem. | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | – |

| protects my rights and entitlements | The social worker makes sure that I am aware of my rights and that they are protected. This means making sure that I am fairly treated, and that I am receiving any benefits that I am entitled to. | 28 (90.3) | 3 (9.7) | – |

| is non-judgemental | The social worker does not criticise me or my choices. They do not try to tell me how to live my life based on their own judgements or those of wider society. They help me to live according to my own values. | 27 (87.1) | 4 (12.9) | – |

| arranges access to other services | The social worker works closely with others to get the help I need. They might make referrals to other NHS or social care services, or (with my permission) talk with colleges, employers, voluntary services and others. | 26 (83.9) | 5 (16.1) | – |

| looks carefully for signs of abuse and neglect | The social worker is experienced in identifying different forms of abuse and neglect (physical, verbal, emotional, financial and sexual). | 24 (80.0) | 4 (12.9) | 2 (6.5) |

| understands why people become vulnerable | The social worker is experienced in helping people to avoid being exploited or discriminated against. This may be because of mental health, disability, ethnicity, poverty or other reasons. | 23 (74.2) | 8 (25.8) | – |

| suggests different ways of helping me, and does not concentrate on medication alone | The social worker will consider, and inform me about, different options that might be helpful. These could include attending social and leisure activities, helping with life skills, education, work and talking therapies. | 20 (64.5) | 9 (29.0) | 2 (6.4) |

| is a reliable and continuous point of contact | The social worker can be relied upon to do what they say they will do. It will be the same social worker I see each time. | 17 (54.8) | 13 (41.9) | 1 (3.2) |

| understands how people’s difficulties can vary from time-to-time | The social worker knows that how someone feels one day can be quite different to another day. By understanding this, they can see when I need more support. | 13 (41.9) | 15 (48.4) | 3 (9.7) |

| is compassionate | The social worker is caring and considerate. They show empathy and understanding of how my past and current problems affect me. | n/a | ||

| Attribute: ‘The social worker …’ . | Definition . | Rating of ‘uniqueness to social work’, n (%) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High . | Medium . | Low . | ||

| thinks about my whole life, not just my illness | The social worker is interested in all the things that are important to me and my life, not just the symptoms of my mental health problem. | 29 (93.5) | 2 (6.5) | – |

| protects my rights and entitlements | The social worker makes sure that I am aware of my rights and that they are protected. This means making sure that I am fairly treated, and that I am receiving any benefits that I am entitled to. | 28 (90.3) | 3 (9.7) | – |

| is non-judgemental | The social worker does not criticise me or my choices. They do not try to tell me how to live my life based on their own judgements or those of wider society. They help me to live according to my own values. | 27 (87.1) | 4 (12.9) | – |

| arranges access to other services | The social worker works closely with others to get the help I need. They might make referrals to other NHS or social care services, or (with my permission) talk with colleges, employers, voluntary services and others. | 26 (83.9) | 5 (16.1) | – |

| looks carefully for signs of abuse and neglect | The social worker is experienced in identifying different forms of abuse and neglect (physical, verbal, emotional, financial and sexual). | 24 (80.0) | 4 (12.9) | 2 (6.5) |

| understands why people become vulnerable | The social worker is experienced in helping people to avoid being exploited or discriminated against. This may be because of mental health, disability, ethnicity, poverty or other reasons. | 23 (74.2) | 8 (25.8) | – |

| suggests different ways of helping me, and does not concentrate on medication alone | The social worker will consider, and inform me about, different options that might be helpful. These could include attending social and leisure activities, helping with life skills, education, work and talking therapies. | 20 (64.5) | 9 (29.0) | 2 (6.4) |

| is a reliable and continuous point of contact | The social worker can be relied upon to do what they say they will do. It will be the same social worker I see each time. | 17 (54.8) | 13 (41.9) | 1 (3.2) |

| understands how people’s difficulties can vary from time-to-time | The social worker knows that how someone feels one day can be quite different to another day. By understanding this, they can see when I need more support. | 13 (41.9) | 15 (48.4) | 3 (9.7) |

| is compassionate | The social worker is caring and considerate. They show empathy and understanding of how my past and current problems affect me. | n/a | ||

n/a, not applicable.

Stage 5: designing the BWS schedule

A Case 1 (or ‘object case’) BWS study was designed (Louviere and Flynn, 2010). These work by presenting participants with a list of attributes (‘choice set’) and asking them to select the best and worst amongst them (in this instance, the ‘most important’ and the ‘least important’). This task then repeats, but with a different selection of attributes each time, through to the end of the exercise. A complete ranking of all attributes would demand complete pairwise comparisons requiring each participant to engage with 210 = 1,024 choice sets. BWS experiments instead use designs to present only a subset, with these being chosen to achieve optimal estimation properties.

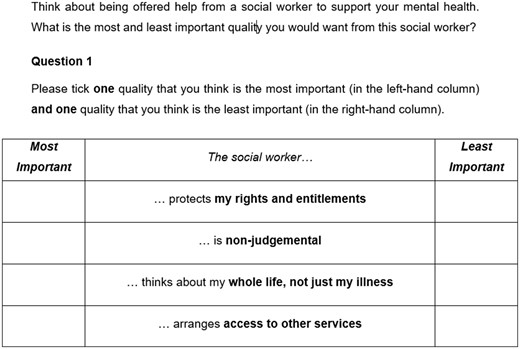

A balanced incomplete block design (BIBD) was selected from a catalogue of efficient designs (Cochran and Cox, 1992) and a corresponding BWS plan was selected. This meant that each participant would engage with just fifteen choice sets, with each of these containing four attributes (which vary through each choice set). Each attribute occurred six times across the fifteen choice sets. Figure 1 illustrates how these choice sets appeared on paper. The BWS instrument also included brief questions collecting socio-demographic details, service use history and a self-assessed general health question. An open text box was available for people to record their diagnosis(es), but with an explicit option for people who preferred not to say.

Stage 6: piloting and implementation

The BWS was piloted through face-to-face interviews with the researchers, using a think-aloud technique (Beatty and Willis, 2007). The pilots involved five service users recruited through networks provided by the lay members of the research team. They had no prior knowledge of the BWS research. The pilots were successful, but highlighted the importance of reassuring participants that there were no right or wrong answers, and also that the researchers understood that ‘least important’ answers are not necessarily ‘unimportant’.

The main fieldwork sought participants drawn from the social worker caseloads in working-age adult Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs) across five mental health trusts in England. These trusts provided services to a mix of urban, rural and mixed localities, including London-based CMHTs, and included both relatively deprived and prosperous regions. Eligible participants all had capacity to consent to research, were living at home, and had experience of support from a social worker. The required sample size for any BWS analysis cannot be estimated a priori, but a ‘rule of thumb’ would suggest around 100 participants would be necessary (de Bekker-Grob et al., 2015).

The final data were analysed using specialist statistical software (Stata). Simple descriptive analyses were complemented by a conditional logit model, using procedures described within Louviere et al. (2015). A conditional logit model is a non-linear regression appropriate for analysing choice data. The assumption taken was that choices were made sequentially so that the individual chose the ‘most important’ option first and so, in effect, one fewer options were available for the ‘least important’ option (assuming participants ruled out choosing the same attribute as being simultaneously ‘most’ and ‘least’ important).

Researchers sought fully informed and signed consent from each participant. Ethical approval was granted by the North of Scotland (2) Research Ethics Committee: (grant number: 17/NS/0127).

Findings

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 2. Most of the sample reported being within mental health services for over five years, and over two-thirds had experience of prior admissions to mental health wards. Over half the sample described their general health as only ‘fair’ or ‘poor’. The open text diagnosis box was used by three-quarters of the sample (N = 106), and coding was necessarily crude (using the first mentioned diagnosis where more than one was presented), serving merely to illustrate the range of problems being supported. Most respondents reported a diagnosis of schizophrenia (n = 33), bipolar (n = 22), or other mood/anxiety disorders (n = 31). Sixteen reported a personality disorder, and four reported an organic illness.

| Characteristic . | n . | % . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (missing = 1) | Female | 73 | 51.0 |

| Male | 70 | 49.0 | |

| Age (years) (missing = 1) | <30 | 27 | 18.9 |

| 31–50 | 58 | 40.6 | |

| >51 | 58 | 40.6 | |

| Ethnicity (missing = 1) | White UK | 125 | 87.4 |

| White other | 6 | 4.2 | |

| Black | 4 | 2.8 | |

| Asian | 8 | 5.6 | |

| Length of time in mental health services (years) (missing = 3) | <1 | 3 | 2.1 |

| 1–5 | 48 | 34.0 | |

| 6–10 | 34 | 24.1 | |

| >10 | 56 | 39.7 | |

| Whether ever admitted to a mental health ward (missing = 2) | No | 49 | 34.5 |

| Yes, once | 23 | 16.2 | |

| Yes, more than once | 70 | 49.3 | |

| Self-rated general health (missing = 1) | Excellent | 3 | 2.1 |

| Very good | 15 | 10.5 | |

| Good | 42 | 29.4 | |

| Fair | 56 | 39.2 | |

| Poor | 27 | 18.9 | |

| Characteristic . | n . | % . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (missing = 1) | Female | 73 | 51.0 |

| Male | 70 | 49.0 | |

| Age (years) (missing = 1) | <30 | 27 | 18.9 |

| 31–50 | 58 | 40.6 | |

| >51 | 58 | 40.6 | |

| Ethnicity (missing = 1) | White UK | 125 | 87.4 |

| White other | 6 | 4.2 | |

| Black | 4 | 2.8 | |

| Asian | 8 | 5.6 | |

| Length of time in mental health services (years) (missing = 3) | <1 | 3 | 2.1 |

| 1–5 | 48 | 34.0 | |

| 6–10 | 34 | 24.1 | |

| >10 | 56 | 39.7 | |

| Whether ever admitted to a mental health ward (missing = 2) | No | 49 | 34.5 |

| Yes, once | 23 | 16.2 | |

| Yes, more than once | 70 | 49.3 | |

| Self-rated general health (missing = 1) | Excellent | 3 | 2.1 |

| Very good | 15 | 10.5 | |

| Good | 42 | 29.4 | |

| Fair | 56 | 39.2 | |

| Poor | 27 | 18.9 | |

| Characteristic . | n . | % . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (missing = 1) | Female | 73 | 51.0 |

| Male | 70 | 49.0 | |

| Age (years) (missing = 1) | <30 | 27 | 18.9 |

| 31–50 | 58 | 40.6 | |

| >51 | 58 | 40.6 | |

| Ethnicity (missing = 1) | White UK | 125 | 87.4 |

| White other | 6 | 4.2 | |

| Black | 4 | 2.8 | |

| Asian | 8 | 5.6 | |

| Length of time in mental health services (years) (missing = 3) | <1 | 3 | 2.1 |

| 1–5 | 48 | 34.0 | |

| 6–10 | 34 | 24.1 | |

| >10 | 56 | 39.7 | |

| Whether ever admitted to a mental health ward (missing = 2) | No | 49 | 34.5 |

| Yes, once | 23 | 16.2 | |

| Yes, more than once | 70 | 49.3 | |

| Self-rated general health (missing = 1) | Excellent | 3 | 2.1 |

| Very good | 15 | 10.5 | |

| Good | 42 | 29.4 | |

| Fair | 56 | 39.2 | |

| Poor | 27 | 18.9 | |

| Characteristic . | n . | % . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (missing = 1) | Female | 73 | 51.0 |

| Male | 70 | 49.0 | |

| Age (years) (missing = 1) | <30 | 27 | 18.9 |

| 31–50 | 58 | 40.6 | |

| >51 | 58 | 40.6 | |

| Ethnicity (missing = 1) | White UK | 125 | 87.4 |

| White other | 6 | 4.2 | |

| Black | 4 | 2.8 | |

| Asian | 8 | 5.6 | |

| Length of time in mental health services (years) (missing = 3) | <1 | 3 | 2.1 |

| 1–5 | 48 | 34.0 | |

| 6–10 | 34 | 24.1 | |

| >10 | 56 | 39.7 | |

| Whether ever admitted to a mental health ward (missing = 2) | No | 49 | 34.5 |

| Yes, once | 23 | 16.2 | |

| Yes, more than once | 70 | 49.3 | |

| Self-rated general health (missing = 1) | Excellent | 3 | 2.1 |

| Very good | 15 | 10.5 | |

| Good | 42 | 29.4 | |

| Fair | 56 | 39.2 | |

| Poor | 27 | 18.9 | |

Summary statistics for BWS scores

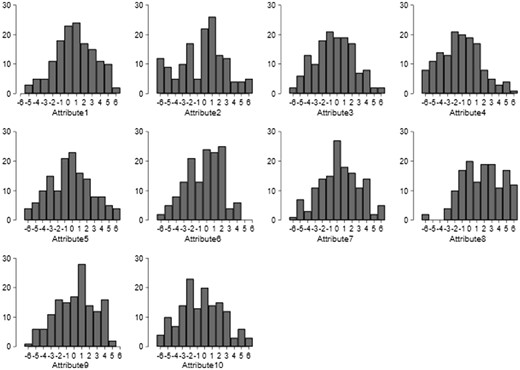

BWS analysis began with the calculation of Best minus Worst (B-W) scores. That is, for each attribute, the total number of times a participant selected it as ‘worst’ was subtracted from the number of times it was chosen as ‘best’. Since each attribute appeared six times in the choice tasks, for each person this could take the value of −6 (chosen as worst every time it appeared) through to +6 (chosen as best every time it appeared). Across all respondents, mean values greater than zero indicate that the attribute was selected as ‘best’ more often than ‘worst’.

Figure 2 displays the frequency density histograms for the B-W scores of all ten attributes. The shapes illustrate some trends from the choice task. For example, scores for some attributes (e.g. #1 ‘thinks about my whole life, not just my illness’) followed a relatively normal-shaped distribution around a positive mean, but still with a significant proportion of the distribution with negative B-W scores indicating it was not universally a dominant choice. Indeed, only one attribute (#8 ‘reliable and continuous point of contact’) showed a consistent positive B-W score for the large majority of choices made. Attribute #2 (‘protects my rights and entitlements’) appeared to divide opinion, with 10 per cent of all respondents scoring this as the least important attribute all six times it appeared in the questionnaire, yet for many others this appeared a more attractive option. Similarly, attribute #5 (‘looks carefully for signs of abuse and neglect’) had surprisingly high proportion of responses at extreme values indicating that this is both a (relatively) very important and very unimportant attribute for different respondents. Summary statistics are presented in Table 3, including the mean B-W scores for each attribute and its associated rank order.

Histograms of frequency density for B-W scores for ten attributes

| Attribute . | Mean B-W . | Rank . | SE . | SD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| thinks about my whole life, not just my illness (03) | 0.826 | 2 | 0.208 | 2.493 |

| protects my rights and entitlements (01) | −0.361 | 6 | 0.262 | 3.142 |

| is non-judgemental (02) | −0.368 | 7 | 0.220 | 2.636 |

| arranges access to other services (04) | −1.208 | 10 | 0.229 | 2.743 |

| looks carefully for signs of abuse and neglect (06) | −0.215 | 5 | 0.240 | 2.878 |

| understands why people become vulnerable (05) | −0.389 | 7 | 0.218 | 2.618 |

| suggests different ways of helping me, and does not concentrate on medication alone (08) | 0.347 | 3 | 0.225 | 2.705 |

| is a reliable and continuous point of contact (07) | 1.722 | 1 | 0.224 | 2.685 |

| understands how people’s difficulties can vary from time-to-time (09) | 0.181 | 4 | 0.215 | 2.582 |

| is compassionate (010) | −0.438 | 8 | 0.241 | 2.894 |

| Attribute . | Mean B-W . | Rank . | SE . | SD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| thinks about my whole life, not just my illness (03) | 0.826 | 2 | 0.208 | 2.493 |

| protects my rights and entitlements (01) | −0.361 | 6 | 0.262 | 3.142 |

| is non-judgemental (02) | −0.368 | 7 | 0.220 | 2.636 |

| arranges access to other services (04) | −1.208 | 10 | 0.229 | 2.743 |

| looks carefully for signs of abuse and neglect (06) | −0.215 | 5 | 0.240 | 2.878 |

| understands why people become vulnerable (05) | −0.389 | 7 | 0.218 | 2.618 |

| suggests different ways of helping me, and does not concentrate on medication alone (08) | 0.347 | 3 | 0.225 | 2.705 |

| is a reliable and continuous point of contact (07) | 1.722 | 1 | 0.224 | 2.685 |

| understands how people’s difficulties can vary from time-to-time (09) | 0.181 | 4 | 0.215 | 2.582 |

| is compassionate (010) | −0.438 | 8 | 0.241 | 2.894 |

| Attribute . | Mean B-W . | Rank . | SE . | SD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| thinks about my whole life, not just my illness (03) | 0.826 | 2 | 0.208 | 2.493 |

| protects my rights and entitlements (01) | −0.361 | 6 | 0.262 | 3.142 |

| is non-judgemental (02) | −0.368 | 7 | 0.220 | 2.636 |

| arranges access to other services (04) | −1.208 | 10 | 0.229 | 2.743 |

| looks carefully for signs of abuse and neglect (06) | −0.215 | 5 | 0.240 | 2.878 |

| understands why people become vulnerable (05) | −0.389 | 7 | 0.218 | 2.618 |

| suggests different ways of helping me, and does not concentrate on medication alone (08) | 0.347 | 3 | 0.225 | 2.705 |

| is a reliable and continuous point of contact (07) | 1.722 | 1 | 0.224 | 2.685 |

| understands how people’s difficulties can vary from time-to-time (09) | 0.181 | 4 | 0.215 | 2.582 |

| is compassionate (010) | −0.438 | 8 | 0.241 | 2.894 |

| Attribute . | Mean B-W . | Rank . | SE . | SD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| thinks about my whole life, not just my illness (03) | 0.826 | 2 | 0.208 | 2.493 |

| protects my rights and entitlements (01) | −0.361 | 6 | 0.262 | 3.142 |

| is non-judgemental (02) | −0.368 | 7 | 0.220 | 2.636 |

| arranges access to other services (04) | −1.208 | 10 | 0.229 | 2.743 |

| looks carefully for signs of abuse and neglect (06) | −0.215 | 5 | 0.240 | 2.878 |

| understands why people become vulnerable (05) | −0.389 | 7 | 0.218 | 2.618 |

| suggests different ways of helping me, and does not concentrate on medication alone (08) | 0.347 | 3 | 0.225 | 2.705 |

| is a reliable and continuous point of contact (07) | 1.722 | 1 | 0.224 | 2.685 |

| understands how people’s difficulties can vary from time-to-time (09) | 0.181 | 4 | 0.215 | 2.582 |

| is compassionate (010) | −0.438 | 8 | 0.241 | 2.894 |

Regression analysis

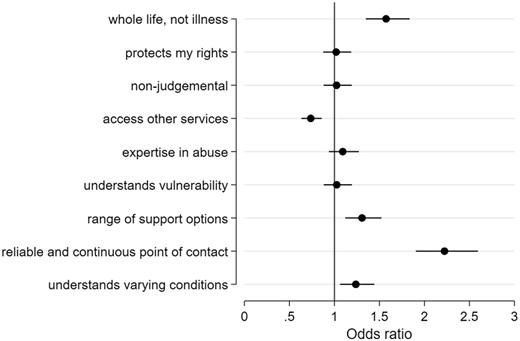

A more formal approach to presenting strength of preference is through a conditional logistic regression. In such models, the estimated odds ratios show how much more, or less, likely an average respondent was to choose that attribute compared to a reference attribute. That reference attribute can be any one of the ten, but it helps with interpretation to have an a priori rationale for the chosen reference. In this study, #10 ‘is compassionate’ was chosen, as the attribute rated as the least unique to social work. In the subsequent analysis, the odds of choosing that reference attribute is set at one, with other odds ratios then interpreted accordingly (for example, an odds ratio of 1.2 would indicate that that attribute was 20 per cent more likely to be chosen, on average, than the reference).

Results are illustrated in Figure 3, with full regression output presented as Supplementary Material. Attributes are ordered identically to Table 1 (in order of ‘uniqueness’ to social work). Relative to the reference attribute (#10 ‘compassionate’), respondents were over two times more likely to choose ‘reliable and continuous point of contact’ as the best attribute in any given choice set. Of the more ‘specialist’ social work attributes, attention to ‘whole life, not just my illness’ stood out as an important priority. Respondents attached least value to ‘arranging access to other services’. Relative preferences for four of the attributes could not be distinguished from each other, nor from the reference attribute.

Coefficients and confidence intervals from conditional logistic regression on BWS choices (reference attribute = ‘is compassionate’)

Lay members of the research team asked for further analysis for subgroups of participants to understand potential differences in preferences (results provided as Supplementary Material). Relative to the reference attribute, men in this sample valued protection of rights and entitlements more than women, whilst respondents aged under fifty years placed greater value on non-judgemental approaches than those aged fifty years or over. Compassionate approaches appeared relatively more important to those with a prior admission to a mental health ward, whilst ‘arranging access to other services’ had more relative value for those referred within the last five years than those with a long history of services. Those in good or better health at the time of interview placed a high value on social workers understanding that mental health needs can vary over time. Notwithstanding this variation in preferences, the importance of reliable and continuous social work support dominated all other attributes for all subgroups.

Discussion

The research finds the overriding concern amongst service users was that their social worker must provide a continuous and reliable source of support. This was true regardless of the individual characteristics and experience of service use. Whilst much policy attention has been given to achieving continuity between services, through care coordination as part of integrated multidisciplinary teams, ‘relational continuity’ with the same care coordinator is more challenging to achieve (Digel Vandyk et al., 2013). A large national cross-section of schizophrenia service users in England and Wales found that 42 per cent had experienced a change of care coordinator in the preceding twelve months, with over 10 per cent reporting multiple changes (Sanatinia et al., 2016). An earlier and smaller, but more robust, study in two mental health trusts found that a service user changed care coordinator every eight months (Bindman et al., 2000). There appears to be a positive relationship between relational continuity and quality of life, though attributing causality is difficult (Catty et al., 2013).

Qualitative data unequivocally highlight the negative implications of interruptions to relational continuity. Partly this forms a frustration of having to ‘tell my whole life story again and again’ after ‘being thrown around backwards and forwards between different social workers’ (interviewee in Biringer et al., 2017, p. 7). Similarly, unreliable practitioners who miss appointments or do not deliver what is agreed can add to a sense of anxiety that can already accompany receipt of mental health services (Biringer et al., 2017). However, it is the quality of relationships that may suffer most. Participants in Jones et al.’s (2009) study found that service users experiencing disrupted care relationships began to anticipate that future care coordinators would also be transient. Repeated retelling of the same narratives also became automated in the minds of service users, who became experts at condensing their stories to a collection of symptoms, with one participant saying she ‘objectified herself’ in order to save time (Jones et al., 2009). The lay members of the research team turned the findings into a question: ‘how can you even do social work if you can’t work with someone consistently?’

What are the implications of this for the profession? Arguably, care continuity is not a feature of any individual profession, but rather a system-level factor. Since individual social workers have little control over continuity, with continual pressures through new referrals in poorly resourced service settings, it is difficult to make simple recommendations for practice.

The second most valued attribute, and the most unique to social work according to the expert panel (see Stage 2 of section ‘Method’), was attention paid to ‘my whole life, not just my illness’. This attribute speaks to the broader perspectives of the causes and consequences of mental health problems beyond those evaluated by traditional medical approaches to psychiatric illness. The social determinants of mental health need are well documented, as are the structural disadvantages and discrimination faced by service users, trapping many in a vicious cycle of social exclusion and internalised stigma (Tew et al., 2012). Yet, in attending to these needs, social workers can also identify possibilities for recovery by building on personal and social resources. Together, the social work approach empowers service users to enact the changes they wish to see.

This is not the first study to examine whether service users value a whole-person approach (Beresford, 2007); however, it is the first (to our knowledge) to quantify their strength of feeling and the relative importance of different elements of this, particularly in mental health services. Returning to Nathan and Webber's (2010) challenge for the profession to use service user voices in making the case for social work, the present study finds strong evidence that whole-person approaches are territory where social workers make a distinct contribution, and that service users recognise and value this over and above nine other possible attributes.

The least valued attribute was ‘arranging access to other services’, which was defined as being either through formal referral processes (in the case of health or local authority services), or through informal liaison with other community-based organisations, such as voluntary groups, employers and other networks. Given that substantial social work time is on this type of activity (Jacobs et al., 2013), this may give professionals pause for thought as to whether service users require this to be undertaken to the same extent. Alternatively, it may suggest that service users need to be more involved in deciding what this activity entails and why it may help them. Some evidence has suggested that liaison activities are important to user outcomes (Bjorkman and Hansson, 2000), but perhaps this benefit is not effectively communicated to service users. Potentially, this finding also challenges some elements of asset-based approaches to social care, which seek to marshal potential social networks and other community resources. Lay members of the research team perceived a scepticism about whether such support was accessible and sustainable, echoing critique expressed elsewhere (Daly and Westwood, 2018). They also noted that this attribute was particularly unappealing to those with the longest experience of mental health support, perhaps indicating that other sources of help had been exhausted. Some participants may even have inferred that these liaison activities indicate social workers ‘opting out’ of care, which may contribute to those discontinuities noted above. Admittedly, this is speculative interpretation and the true causes of this result may be many, varied and/or subtle. However, as a minimum, the case for this role needs to be more clearly made to service users if it is to be regarded as valuable.

That preferences did vary by service user characteristic is important to reflect upon. Men were significantly more likely to value ‘protecting my rights and entitlements’ relative to the reference attribute. The lay members of the research team deliberated on whether this reflected gendered attitudes to managing household finances, which possibly extend to concern over whether any rights to benefits, or other sources of social welfare, had been fully exercised. However, the group were also conscious of reinforcing a stereotype themselves. There was also significant variation in attitude to ‘non-judgemental’ approaches to mental health. For the full sample, this was not valued more than the reference attribute, but for sub-groups this was not the case. Specifically, younger people, those with no experience of admission to mental health wards, and those more recently referred to mental health services, valued non-judgemental attitudes more than others in the sample. Lay members of the research team interpreted this as meaning that older service users, with longer experience of support services in general, may feel desensitised to professional opinion and judgement. A final heterogeneity in preferences was noted according to self-assessed health. Those who rated their current health and good or excellent more highly valued social work that recognised how mental health needs can vary from day-to-day. Presumably, this reflected a view amongst those feeling ‘well’ that their mental health needs can fluctuate, and social workers need to be alert to this.

Limitations

The findings of this research must be interpreted in light of its limitations. An important critique relates to whether the approach taken to identifying ‘specialist’ social work qualities is credible. Certainly, to take an example, social workers will widely recognise ‘attention to a person’s whole life, not just their illness’ as being central to social models of mental health. A review of the distinct contribution of mental health social work in Northern Ireland recently concluded that a ‘holistic approach to understanding people and the personal, family, social, economic and environmental factors that influence their lives’ is a central feature of the role (Office of Social Services, 2019, p. 14). However, it is not clear if other professions would necessarily agree. Research currently underway by the authors is examining different professional views of mental health social work, and will address the degree of inter-professional agreement on social work’s distinctive qualities in mental health.

Additional limitations related to the nature of the BWS exercise. First, the BWS implicitly represents social work as being the sum of its individual attributes, and assumes that these are mutually exclusive. The complexity of social work is such that it cannot be reduced to a list of essential separate ingredients, which in practice are deployed in combination rather than alone. Secondly, the focus on just ten attributes inevitably leaves much of the social work role unrepresented in the research. However, by making a simpler representation of social work (as in a BWS), it proves possible to reveal relative preferences for the different features of the work. Thirdly, it is important to recognise the subjectivity of the terms used in the exercise. For example, ‘rights’, ‘continuity’, ‘abuse’ and ‘vulnerability’ are all multidimensional constructs, and different respondents may have focused on different interpretations. A final note of caution is that preferences represented in this study are all relative between the ten attributes presented. Even those valued weakly in this study could nevertheless be important in absolute terms, when compared against the complete set of possible social work attributes. The decision to limit the attribute set to just ten was largely pragmatic, since BWS exercises can be challenging to administer (and burdensome for participants) as the attribute list grows.

Practice implications

There is a widespread misunderstanding about social work’s role in mental health (ComRes, 2017). This is detrimental to the profession and its practice. As a relationship-based profession, part of the efficacy of social work will hinge on the service user’s understanding of the social worker’s role and their belief system about how they will be helped. Furthermore, international evidence points to social workers experiencing reduced job satisfaction where they perceive a lack of clarity over their work (Acker, 2004). The new study presented here provides evidence that service users highly value social workers’ specialist role in achieving a holistic understanding of a person and how mental health profoundly affects (and is affected by) wider social aspects of their life. The social model of mental health is a fundamental aspect of social work practice, and which social workers can legitimately claim as their distinct and unique contribution to mental health care. Given that it is also in such high demand, social workers may find it beneficial to focus on this when describing their expertise to service users.

Another implication relates to social workers’ role in facilitating access to other community services and resource. This study suggests that social workers should not presume that their role in promoting access to local assets will be self-evidently seen as beneficial to service users, who may feel cynicism towards solutions that are outside of the social work/service user relationship. In a context of steadily declining community investment through local authority austerity, and service receipt patterns often involving frequent changes of care coordination, it may be that service users will baulk at the idea that the solutions to their problems involve social workers looking elsewhere for help. Indeed, they may fear a trade-off between time spent ‘with’ them and time spent ‘on their behalf’, choosing the former in such a dichotomy.

Finally, the strength of feeling expressed about continuity of care is such that social work as a profession must take the implication seriously. Care continuity problems may often stem from systemic causes outside of the individual social worker’s control, and it will be for the profession as a whole, together with allied disciplines and service users, to continue to raise attention to fragmented service arrangements. However, some poor practices can compound problems. Careful preparation for any necessary interruptions or onward referrals are essential, without which service users may experience ‘depersonalised transitions’ (Jones et al., 2009).

Conclusions

The research highlights that service users highly value social work for its focus on the ‘whole person’, drawing upon social features of mental health beyond immediate clinical symptoms. This, for many professionals, is the bedrock of social work. That this is recognised and valued so highly by service users can be used as a way of promoting the ‘value-added’ aspects of the profession. This research also finds that service users value support that is reliable and continuous, and that interruptions (e.g. through staff turnover or curtailed duration of support) are likely to badly undermine the value of social work to the end-user. However, not everything a social worker does has equal value to all people, and if social work is to truly co-produce services, these preferences should be acknowledged and understood. Respondents did not see high value in social workers acting as the broker between different services or organisations, despite other evidence of the efficacy of such work. Service users need to be more closely involved in understanding and defining such activities, to render them more individualised and person specific.

Acknowledgements

This article presents independent research funded by the NIHR School for Social Care Research. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR SSCR, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care. The authors acknowledge the support of one other Lay Member of the Research Team who contributed as an equal partner but who preferred not to be named. The researchers are also grateful to Drs Caroline Vass and Stuart Wright for their advice and to the staff of Humber NHS Foundation Trust.

Funding

The research was funded by the NIHR School for Social Care Research.

Conflict of Interest: M.W. is a member of the Editorial Board of the British Journal of Social Work.

References

All Party Parliamentary Group on Social Work (

ComRes (

Office of Social Services (

Social Work Task Force (