-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jian Tao, Haiyan Ma, Xianchun Zeng, Malignant paraganglioma of the prostate invading the bladder and bilateral seminal vesicles: a case report, BJR|Case Reports, Volume 10, Issue 4, July 2024, uaae024, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjrcr/uaae024

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Malignant paraganglioma (PGL) of the prostate is extremely rare, with only 3 cases reported in the English literature to date. In this article, we present a case of malignant prostatic PGL invading the bladder and bilateral seminal vesicles, in which the patient had a history of long-term haematuria and normal serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) level, and was misdiagnosed as a bladder tumour invading the prostate preoperatively. As this case belongs to functional tumour, there is a risk of developing hypertensive crisis during diagnostic biopsy or radical resection. The CT manifestations of prostatic PGL are characteristic, but its imaging features are rarely described due to the rarity of the tumour site. Meanwhile, improving the comprehensive understanding of CT, MRI, functional imaging, and clinical features of prostate PGL is conducive to make the correct diagnosis before surgery and ensure the safety of surgical treatment.

Case presentation

A 49-year-old man who was admitted to our hospital due to the discovery of gross haematuria for 4 years, accompanied by frequent urination, urgent urination, urinary pain, dribbling urine, and increased nocturnal urination (3-4 times per night). On admission, the patient's blood pressure was found to be elevated, fluctuating between 138-183/67-92 mmHg.

Investigations and imaging findings

On digital rectal examination, there was a palpable enlargement of the prostate gland, which was more evident on the left side, without nodules. Urine routine examination showed a significant increase in leukocytes (6983 cells/µL, normal range: 0-8 cells/µL) and erythrocytes (716 cells/µL, normal range: 0-6 cells/µL). Blood biochemistry tests showed that free prostate specific antigen (FPSA) (0.05 ng/mL) and total prostate specific antigen (TPSA) (0.45 ng/mL) were within normal limits, while dopamine (312.4 pmol/L, normal range: 0.5-5.0 pmol/L) and norepinephrine (12041.8 pmol/L, normal range: 615-3240 pmol/L) were significantly elevated.

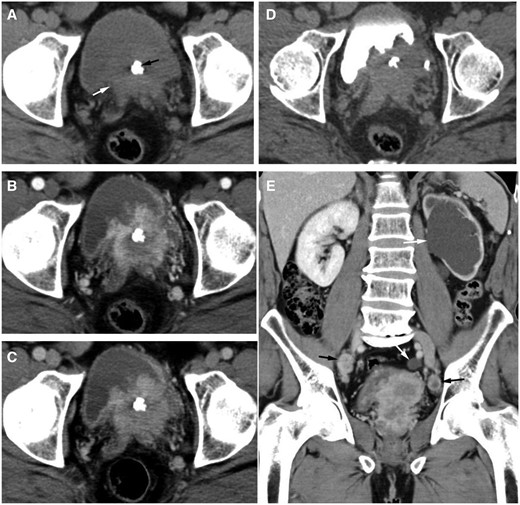

For the initial investigation of the patient, non-contrast and contrast-enhanced CT scans of the urinary system were acquired separately. The cortical phase is 30 s after-injection, the parenchymal phase is 85 s post-injection, and the excretory phase is 25 min post injection. Unenhanced CT of the urinary system showed an isodense soft tissue mass with an ill-defined border in the prostate, the CT value was 40 HU, and nodular calcification could be seen within the mass. Tumour infiltration of the left bladder trigone and bilateral seminal vesicles could be seen on enhanced CT of the urinary system. The tumour showed heterogeneous and significant enhancement with a visible patchy area of low-density necrosis in the centre. The size of the tumour was 6.8 cm × 6.5 cm × 3.0 cm. The CT values of the most significantly-enhanced area in the tumour on the renal cortical phase and parenchymal phase were 150 and 113 HU, respectively. Nodular filling defects could be seen in the bladder cavity on the renal excretory phase. Coronal reconstructed image of the enhanced CT showed severe left hydronephrosis and hydroureter, with multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the pelvis. The left side are located in the region of the obturator lymph nodes and the right side are located in the region of the internal and external iliac lymph nodes. The short diameter of the largest lymph node was 19 mm. The enhancement pattern of the lymph node was similar to the primary prostate tumour. The plain CT value was 39 HU, and the CT values of the most significantly enhanced area on the renal cortical phase and parenchymal phase were 162 and 106 HU, respectively (Figure 1).

(A) The cross-sectional image of the plain CT shows an isodense soft tissue mass with ill-defined border in the prostate (white arrow), the CT value was 40 HU, and nodular calcification (black arrow) could be seen within the mass. (B-D) Axial contrast-enhanced CT images showed that the tumour invaded the left bladder trigone and bilateral seminal vesicles, and the tumour showed heterogeneous and significant enhancement with a visible patchy area of low-density necrosis in the center. The CT values of the most significant enhancement area on the renal cortical phase (B) and parenchymal phase (C) were 150 and 113 HU, respectively. On the renal excretory phase (D), nodular filling defects were observed in the bladder cavity. (E) Coronal reconstructed image of the enhanced CT showed severe left hydronephrosis and hydroureter (white arrow), with multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the pelvis. The left side are located in the region of the obturator lymph nodes and the right side are located in the region of the internal and external iliac lymph nodes (black arrow). The short diameter of the largest lymph node was 19 mm. The enhancement pattern of lymph node was similar to the primary prostate tumour. The plain CT value was 39 HU, and the CT values of the most significant enhancement area on the renal cortical phase and parenchymal phase were 162 and 106 HU, respectively.

Differential diagnosis

In this case, the possibility of prostate adenocarcinoma should be considered first on imaging. However, the patient had a history of long-term haematuria and normal serum PSA level, while CT imaging shows that the tumour protrudes into the bladder cavity, and nodular filling defects could be seen on the renal excretory phase. Therefore, the possibility of bladder tumour invading the prostate was finally considered. Other atypical prostate primaries such as prostate neuroendocrine tumour, lymphoma, or sarcoma may have a similar appearance on CT, so it is necessary to distinguish them from prostate adenocarcinoma and paraganglioma (PGL) (Table 1).

| Primary prostate tumours . | Tumour size (maximum diameter) . | Enhancement pattern (range of HU values) . | Lymph node metastasis . | Tumour calcification . | Biochemical/hormonal profile . | Ideal nuclear medicine tracers . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroendocrine tumour | Large, 7-9 cm | Heterogeneous, intense enhancement (50-70 HU) | Common | No calcification | Low serum PSA level; elevated serum neuron-specific enolase and chromogranin A | 68Ga-DOTA-SSAs |

| Lymphoma | Large, 7-10 cm | Homogeneous, mild to moderate enhancement (10-50 HU) | Absence | No or minimal calcification | Slight or no increase in PSA | 18F-FDG |

| Sarcoma | Large, 7-12 cm | Heterogeneous, moderate to intense enhancement (40-70HU) | Common | No calcification | Serum PSA is normal | 18F-FDG |

| Adenocarcinoma | Small to medium, commonly multifocal, 2-4 cm | Heterogeneous, moderate enhancement (30-50HU) | Common | Uncommon | Increased level of serum PSA | 68Ga-PSMA |

| Paraganglioma | Medium, 3-7 cm | Intense and rapid enhancement (110-140 HU) | Uncommon | Up to 10% may present calcifications | Serum PSA is normal; catecholamine secretion in functional tumour | 123I-MIBG; 68Ga-DOTA-SSAs |

| Primary prostate tumours . | Tumour size (maximum diameter) . | Enhancement pattern (range of HU values) . | Lymph node metastasis . | Tumour calcification . | Biochemical/hormonal profile . | Ideal nuclear medicine tracers . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroendocrine tumour | Large, 7-9 cm | Heterogeneous, intense enhancement (50-70 HU) | Common | No calcification | Low serum PSA level; elevated serum neuron-specific enolase and chromogranin A | 68Ga-DOTA-SSAs |

| Lymphoma | Large, 7-10 cm | Homogeneous, mild to moderate enhancement (10-50 HU) | Absence | No or minimal calcification | Slight or no increase in PSA | 18F-FDG |

| Sarcoma | Large, 7-12 cm | Heterogeneous, moderate to intense enhancement (40-70HU) | Common | No calcification | Serum PSA is normal | 18F-FDG |

| Adenocarcinoma | Small to medium, commonly multifocal, 2-4 cm | Heterogeneous, moderate enhancement (30-50HU) | Common | Uncommon | Increased level of serum PSA | 68Ga-PSMA |

| Paraganglioma | Medium, 3-7 cm | Intense and rapid enhancement (110-140 HU) | Uncommon | Up to 10% may present calcifications | Serum PSA is normal; catecholamine secretion in functional tumour | 123I-MIBG; 68Ga-DOTA-SSAs |

| Primary prostate tumours . | Tumour size (maximum diameter) . | Enhancement pattern (range of HU values) . | Lymph node metastasis . | Tumour calcification . | Biochemical/hormonal profile . | Ideal nuclear medicine tracers . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroendocrine tumour | Large, 7-9 cm | Heterogeneous, intense enhancement (50-70 HU) | Common | No calcification | Low serum PSA level; elevated serum neuron-specific enolase and chromogranin A | 68Ga-DOTA-SSAs |

| Lymphoma | Large, 7-10 cm | Homogeneous, mild to moderate enhancement (10-50 HU) | Absence | No or minimal calcification | Slight or no increase in PSA | 18F-FDG |

| Sarcoma | Large, 7-12 cm | Heterogeneous, moderate to intense enhancement (40-70HU) | Common | No calcification | Serum PSA is normal | 18F-FDG |

| Adenocarcinoma | Small to medium, commonly multifocal, 2-4 cm | Heterogeneous, moderate enhancement (30-50HU) | Common | Uncommon | Increased level of serum PSA | 68Ga-PSMA |

| Paraganglioma | Medium, 3-7 cm | Intense and rapid enhancement (110-140 HU) | Uncommon | Up to 10% may present calcifications | Serum PSA is normal; catecholamine secretion in functional tumour | 123I-MIBG; 68Ga-DOTA-SSAs |

| Primary prostate tumours . | Tumour size (maximum diameter) . | Enhancement pattern (range of HU values) . | Lymph node metastasis . | Tumour calcification . | Biochemical/hormonal profile . | Ideal nuclear medicine tracers . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroendocrine tumour | Large, 7-9 cm | Heterogeneous, intense enhancement (50-70 HU) | Common | No calcification | Low serum PSA level; elevated serum neuron-specific enolase and chromogranin A | 68Ga-DOTA-SSAs |

| Lymphoma | Large, 7-10 cm | Homogeneous, mild to moderate enhancement (10-50 HU) | Absence | No or minimal calcification | Slight or no increase in PSA | 18F-FDG |

| Sarcoma | Large, 7-12 cm | Heterogeneous, moderate to intense enhancement (40-70HU) | Common | No calcification | Serum PSA is normal | 18F-FDG |

| Adenocarcinoma | Small to medium, commonly multifocal, 2-4 cm | Heterogeneous, moderate enhancement (30-50HU) | Common | Uncommon | Increased level of serum PSA | 68Ga-PSMA |

| Paraganglioma | Medium, 3-7 cm | Intense and rapid enhancement (110-140 HU) | Uncommon | Up to 10% may present calcifications | Serum PSA is normal; catecholamine secretion in functional tumour | 123I-MIBG; 68Ga-DOTA-SSAs |

Treatment and outcome

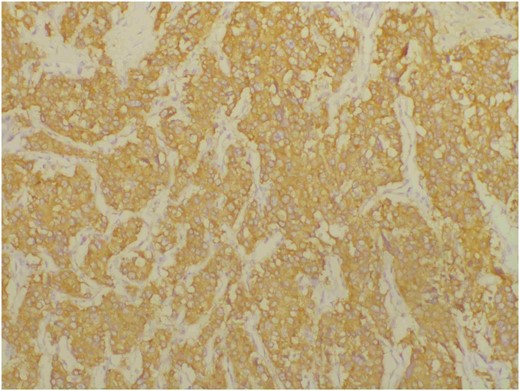

Subsequently, transurethral diagnostic resection of the bladder tumour was performed, and the postoperative pathology was PGL. After discharge, the patient took oral terazosin and irbesartan to control his blood pressure. Three months later, he was readmitted to our hospital for laparoscopic radical prostatectomy and cystectomy, pelvic lymph node dissection, and bilateral ureteral skin fistula. The maximum blood pressure was 196/115 mmHg when touching the tumour during the operation, and the blood pressure decreased rapidly to 75/45 mmHg after tumour resection. On the first postoperative day, the blood pressure fluctuated between 103-142/68-81mmHg after the vasopressor medication was stopped. Gross and microscopic findings of the resected specimen show that the cross section of the tumour is grey-white, solid and moderate texture, and the tumour is diffusely distributed throughout the entire prostate, involving bilateral seminal vesicles and part of the bladder tissue, multiple intravascular tumour thrombus and nerve invasion were observed, with 6/6 pelvic lymph nodes were found to have tumour metastasis. Immunohistochemistry showed that the tumour cells were positive for synaptophysin (Figure 2), chromogranin, neuron-specific enolase, CD56, and S-100 protein. Staining for PSA and CK7 was negative in the tumour cells, and the Ki-67 cell proliferation index was 20%. These results were consistent with prostatic PGL. Two months after surgery, follow-up CT scan showed no signs of tumour recurrence or metastasis.

Immunohistochemical staining for synaptophysin is positive in tumour cells.

Discussion

Paraganglioma, also known as ectopic pheochromocytoma, originates from neuroendocrine cells of the embryonic neural crest. The incidence of PGL is 0.33 cases per 100 000 people per year1 and the majority are located in the abdominal paraaortic region, followed by the bladder, mediastinum, head, and neck.2 Prostatic PGL is extremely rare, with only 12 cases reported to date.3 Although PGL of the bladder is relatively more common clinically, the diagnosis of prostatic PGL invading the bladder was made in this case because CT imaging showed that the main body of the tumour was located in the prostate, and gross and microscopic examination of the resected specimen showed that the tumour was diffusely distributed throughout the entire prostate.

Paraganglioma may secrete catecholamines and can be classified into functional and non-functional PGLs based on the presence or absence of endocrine function. The clinical manifestations of prostatic PGL depend on the functional status of the tumour. Non-functional PGL usually has no specific clinical symptoms, the most common being haematuria and lower urinary tract obstruction due to tumour compression. In addition to these symptoms, functional PGL may present with hypertension, palpitations and excessive sweating due to increased secretion of catecholamines, and laboratory tests may show elevated levels of catecholamines and their metabolites in plasma and urine.4 In this case, the patient's plasma catecholamine levels were significantly elevated, and the clinical manifestations support the corresponding symptoms caused by catecholamine release, which is consistent with functional PGL.

The vast majority of prostate PGLs are benign, only 3 cases of malignant prostate PGLs have been reported in the English literature to date.5–7 There is no histologic criterion to differentiate between benign and malignant PGL, tumour metastasis and vascular invasion are currently accepted pathologic histologic criteria for the diagnosis of malignant PGL.4,8,9 In this case, the tumour invaded the bladder and bilateral seminal vesicles, accompanied by pelvic lymph node metastasis, vascular tumour thrombus and nerve invasion, so the diagnosis is malignant PGL.

The CT imaging findings of this tumour are characteristic. It is noteworthy that nodular calcification can be seen in the centre of the tumour on the plain CT. Up to 10% cases in the literature may present calcifications.10 Calcifications in tumours are due to heterotopic calcification. Factors such as ischaemia due to tumour growth and insufficient blood supply cause necrosis and dystrophic calcification. Calcium salts can be accumulated in the necrotic tissue to form calcification foci.11

According to previous literature report,10 CT shows intense and rapid enhancement of PGL, and the expected degree of enhancement usually reaches over 130 HU. The tumour in this case showed heterogeneous enhancement on contrast-enhanced CT with patchy low-density necrosis in the centre. Compared with plain CT, the solid component of the tumour was significantly enhanced. The degree of enhancement peaks in the renal cortical phase, reaching up to 150 HU, with a maximum enhancement difference of 110 HU, and decreases in the renal parenchymal phase, manifesting as fast in and fast out, allowing separation from other tumours.

MRI has excellent soft tissue resolution, which is essential for tumour localization, characterization, and relationship to adjacent structures. The MRI appearances of prostate PGL are similar to that of pheochromocytoma at other sites. The tumours are generally characterized by low T1 and high T2 signal intensity.12 A high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, particularly those with fat suppression, has been described as characteristic of pheochromocytoma and PGL.13 Prostate adenocarcinomas are commonly multifocal, predominantly arising within the peripheral zone of the prostate as ill-defined areas of homogeneously low T1 and T2 signal intensity.14 Primary transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder typically shows equal T1 and intermediate T2 signal intensity. Therefore, MRI plays an important role in the detection and differential diagnosis of extra-adrenal PGLs.

Compared with CT or MRI, functional imaging often has higher sensitivity for tumour detection. A meta-analysis showed that the diagnostic efficacy of PET/CT with 68Ga-DOTA-SSA for pheochromocytoma and PGL is over 90%,15 and it has become a valuable method in the differential diagnosis of extra-adrenal PGLs.

Learning points

Malignant prostate PGL is exceptionally rare, making it easily misdiagnosed as prostate adenocarcinoma.

CT plays a critical role in the management of prostate PGL, and the imaging manifestations of the tumour are characteristic. The possibility of PGL should be considered when the tumour shows rapid and intense enhancement on multiphase enhanced CT scans, with the degree of enhancement usually reaching over 130 HU.

MRI is essential for tumour localization, characterization, and relationship to adjacent structures. The presence of high-signal intensity on T2-weighted image is a distinguishing feature of pheochromocytoma and PGL, allowing separation from other tumours.

Detection of catecholamine levels in plasma or urine facilitates preoperative diagnosis of functional PGL and reduces the risk of developing hypertensive crisis during surgery.

Funding

This study was supported by Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects No. QKHJC-ZK[2022]256.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Informed consent statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report (including images, case history and data).