-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

K.S. Thomas, J.M. Batchelor, P. Akram, J.R. Chalmers, R.H. Haines, G.D. Meakin, L. Duley, J.C. Ravenscroft, A. Rogers, T.H. Sach, M. Santer, W. Tan, J. White, M.E. Whitton, H.C. Williams, S.T. Cheung, H. Hamad, A. Wright, J.R. Ingram, N.J. Levell, J.M.R. Goulding, A. Makrygeorgou, A. Bewley, M. Ogboli, J. Stainforth, A. Ferguson, B. Laguda, S. Wahie, R. Ellis, J. Azad, A. Rajasekaran, V. Eleftheriadou, A.A. Montgomery, on behalf of the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network’s HI‐Light Vitiligo Trial Team, Randomized controlled trial of topical corticosteroid and home‐based narrowband ultraviolet B for active and limited vitiligo: results of the HI‐Light Vitiligo Trial, British Journal of Dermatology, Volume 184, Issue 5, 1 May 2021, Pages 828–839, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19592

Close - Share Icon Share

Summary

Evidence for the effectiveness of vitiligo treatments is limited.

To determine the effectiveness of (i) handheld narrowband UVB (NB‐UVB) and (ii) a combination of potent topical corticosteroid (TCS) and NB‐UVB, compared with TCS alone, for localized vitiligo.

A pragmatic, three‐arm, placebo‐controlled randomized controlled trial (9‐month treatment, 12‐month follow‐up). Adults and children, recruited from secondary care and the community, aged ≥ 5 years and with active vitiligo affecting < 10% of skin, were randomized 1 : 1 : 1 to receive TCS (mometasone furoate 0·1% ointment + dummy NB‐UVB), NB‐UVB (NB‐UVB + placebo TCS) or a combination (TCS + NB‐UVB). TCS was applied once daily on alternating weeks; NB‐UVB was administered on alternate days in escalating doses, adjusted for erythema. The primary outcome was treatment success at 9 months at a target patch assessed using the participant‐reported Vitiligo Noticeability Scale, with multiple imputation for missing data. The trial was registered with number ISRCTN17160087 on 8 January 2015.

In total 517 participants were randomized to TCS (n = 173), NB‐UVB (n = 169) and combination (n = 175). Primary outcome data were available for 370 (72%) participants. The proportions with target patch treatment success were 17% (TCS), 22% (NB‐UVB) and 27% (combination). Combination treatment was superior to TCS: adjusted between‐group difference 10·9% (95% confidence interval 1·0%–20·9%; P = 0·032; number needed to treat = 10). NB‐UVB alone was not superior to TCS: adjusted between‐group difference 5·2% (95% CI − 4·4% to 14·9%; P = 0·29; number needed to treat = 19). Participants using interventions with ≥ 75% expected adherence were more likely to achieve treatment success, but the effects were lost once treatment stopped. Localized grade 3 or 4 erythema was reported in 62 (12%) participants (including three with dummy light). Skin thinning was reported in 13 (2·5%) participants (including one with placebo ointment).

Combination treatment with home‐based handheld NB‐UVB plus TCS is likely to be superior to TCS alone for treatment of localized vitiligo. Combination treatment was relatively safe and well tolerated but was successful in only around one‐quarter of participants.

Vitiligo causes loss of skin pigmentation, mainly due to autoimmune destruction of melanocytes.1–7 It affects up to 2% of the world’s population, and the age of onset is usually between 10 and 30 years.8–13 Vitiligo has an impact on quality of life, especially if it occurs on visible sites, such as the face and hands.14–16 It can lead to depression and anxiety, low self‐esteem and social isolation.16–19 Current clinical guidelines20 recommend topical corticosteroids (TCSs), topical tacrolimus, narrowband ultraviolet B (NB‐UVB) and combination therapies for vitiligo. However, there are few well‐designed randomized controlled trials assessing NB‐UVB treatment for vitiligo.21

Many people with vitiligo experience frustration in accessing treatment.22–24 NB‐UVB is usually reserved for people with extensive vitiligo and is delivered in secondary care using full‐body units, requiring regular hospital attendance.22 Limited vitiligo can be treated with handheld NB‐UVB devices,25 but studies assessing these have been retrospective, or too small to inform clinical practice.26, 27 Using a handheld NB‐UVB device reduces the need for hospital visits and avoids exposure of unaffected skin to NB‐UVB. Clinical studies have also suggested that treating vitiligo in its early stages is more likely to be beneficial than treating long‐standing vitiligo.27, 28

We report the results of the Home Interventions and Light therapy for the treatment of Vitiligo Trial (Hi‐Light Vitiligo Trial), which evaluated the comparative safety and effectiveness of a potent TCS and handheld NB‐UVB for the management of active limited vitiligo in adults and children.

Patients and methods

The trial protocol has been published previously.29, 30 No changes were made to the eligibility criteria or outcome measures after trial commencement. The study was approved by the Health Research Authority East Midlands (Derby) Research Ethics Committee (14/EM/1173) and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (EudraCT 2014‐003473‐42). Participants or their parents or carers gave written informed consent. The trial was informed by a pilot trial,31 and was registered prior to the start of recruitment (ISRCTN 17160087; 8 January 2015). A full trial report is available through the NIHR Journal series.32

Study design and setting

The study was a multicentre, three‐arm, parallel‐group, pragmatic, placebo‐controlled randomized controlled trial, with nested health economics and process evaluation studies (reported separately).30

Trial interventions were delivered in secondary care across 16 UK hospitals. Participants were identified through secondary care dermatology clinics and general practice mailouts, and by self‐referral. Participants were enrolled for up to 21 months (9 months of treatment, 12 months of follow‐up) and attended hospital clinics on two consecutive days at baseline for recruitment and training, and then at 3, 6 and 9 months to assess outcomes. Follow‐up thereafter was by 3‐monthly questionnaires, by post or email.

Objectives

The study’s objectives were as follows. (1) To evaluate the comparative effectiveness and safety of home‐based interventions for the management of active, limited vitiligo in adults and children, comparing firstly, handheld NB‐UVB vs. potent TCS (mometasone furoate 0·1% ointment); and secondly, a combination of handheld NB‐UVB plus potent TCS vs. potent TCS alone. (2) To assess whether treatment response (if any) is maintained once the interventions are stopped. (3) To compare the cost‐effectiveness of the interventions from a UK National Health Service (NHS) perspective. (4) To understand the barriers and facilitators to adoption of these interventions within the UK NHS. Objectives 3 and 4 are reported elsewhere.30

Participants

Participants were aged > 5 years, with nonsegmental vitiligo limited to approximately 10% or less of body surface area, and at least one vitiligo patch that had been active in the last 12 months (reported by the participant, or parent or carer). Full eligibility criteria are listed in the protocol.29

Interventions

All participants received an NB‐UVB light unit (active or dummy; used on alternate days) and either a TCS (mometasone furoate 0·1% ointment; Elocon®; Merck Sharp & Dohme, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) or vehicle (placebo), applied daily on alternate weeks. Any device found to have an output that had more than ± 20% of the expected mean output, or a dummy device testing positive for any NB‐UVB emission, was returned to the manufacturer. Treatments were continued for up to 9 months, and concomitant medications were logged. Further details of the interventions are provided in the protocol and full trial report.29, 32 Dummy devices were identical to active devices but used special covers that blocked transmission of NB‐UVB. Placebo ointment was identical in appearance to active ointment.

Participants selected up to three patches of vitiligo for assessment: one on each of three anatomical regions (head and neck, hands and feet, and rest of body). One patch was selected as the target for primary outcome assessment and was reported as active (new or changed) within the last 12 months.

Outcomes

The outcomes examined were the core outcome domains for vitiligo.33, 34

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was participant‐reported treatment success at the target patch of vitiligo after 9 months of treatment. This was measured using the Vitiligo Noticeability Scale (VNS),35, 36 with treatment success defined as ‘a lot less noticeable’ or ‘no longer noticeable’ compared with before treatment. Participants used digital images of the target patch before treatment to help inform their assessment.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were as follows. (i) Blinded assessment of treatment success (VNS) at the target patch assessed by a panel of three people with vitiligo, using digital images. (ii) Participant‐reported treatment success for each of the three anatomical regions (all assessed patches) using VNS, assessed at 9 months. (iii) Onset of treatment response at the target patch, assessed by investigators. (iv) Percentage repigmentation at the target patch at 9 months, using blinded clinician assessment of digital images (0–24%, 25–49%, 50–74%, 75–100%). Investigator assessments were used if images at 9 months were unavailable. (v) Quality of life at baseline, end of treatment (9 months) and end of follow‐up (21 months). Disease‐specific quality‐of‐life (VitiQoL, Skindex 29) and generic quality‐of‐life (EuroQol 5 Dimensions 5 Levels; EQ‐5D‐5L) instruments were completed by adults aged > 18 years. Children aged 5–17 years completed the Child Health Utility 9D (generic) and children aged > 11 years also completed the EQ‐5D‐5L (generic). (vi) Maintenance of treatment response assessed by participants for the target patch at 12, 15, 18 and 21 months. (vii) Safety: adverse device effects, and adverse reactions during the treatment phase. (viii) Time burden of treatment: time per session for active NB‐UVB treatment and participant‐reported treatment burden for active TCS and NB‐UVB treatments at 3, 6 and 9 months.

Adherence with treatments was recorded using treatment diaries and was collated at 3‐monthly clinic visits.

Randomization and blinding of allocation and outcome assessment

Participants were randomized 1 : 1 : 1 to receive TCS plus dummy NB‐UVB (TCS group), vehicle ointment plus NB‐UVB (NB‐UVB group), or TCS ointment plus NB‐UVB (combination group). Allocation was minimized by recruiting centre, body region of target patch and age, weighted towards minimizing the imbalance in trial arms with probability 0·8. The randomization sequence was accessed by staff at the recruiting hospital, using a secure web server created and maintained by the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU) to ensure concealment. A central pharmacy (Mawdsleys, Doncaster, UK) distributed the interventions. The pharmacy was notified of the allocation for randomized participants via the web‐based system and trial treatments were sent directly to participants’ homes. Only the NCTU programmer, the pharmacy staff and the NCTU Quality Assurance staff had access to treatment allocations. Additional blinded outcome assessments were performed by a panel of three people with vitiligo (for the primary analysis) and a clinician for the secondary outcome of percentage repigmentation, using digital images taken at baseline and at 9 months.

Statistical methods

Sample size

Assuming that 15% of participants allocated to receive TCS would achieve treatment success,37 372 participants were required to detect a clinically significant absolute difference between groups of 20%, with 2·5% two‐sided alpha and 90% power. Allowing for up to 15% noncollection of primary outcome data at 9 months, the target sample size was 440 participants. A planned sample‐size review by the Data Monitoring Committee after 18 months of recruitment resulted in a recommended increase in sample size to 516 participants.

Analysis

All analyses were prespecified in a statistical analysis plan, which was finalized prior to database lock.29 Amendments to the analysis plan compared with the protocol are summarized in Table S1 (see Supporting Information).

The primary analysis included all participants, regardless of adherence, and with multiple imputation of missing outcome data. Estimates of the analyses were obtained from 30 multiply imputed datasets by applying the combination rules developed by Rubin.38 Prior to primary analysis, baseline characteristics were summarized by treatment arms and the availability of primary outcome at 9 months, in order to check the missing‐at‐random assumption of multiple imputation.

For the primary outcome, the number and percentage of participants achieving ‘treatment success’ were reported for each treatment group at 9 months. Randomized groups were compared using a mixed effects model for binary outcome adjusted by minimization variables. The primary effectiveness parameter for the two comparisons of NB‐UVB alone and combination treatment, each vs. TCS alone, was the difference in the proportion of participants achieving treatment success at 9 months, presented with the 95% confidence interval (CI) and P‐value. By default, risk differences are reported, because these estimates are more clinically intuitive for binary outcomes. However, where models estimating risk difference did not converge, odds ratios are reported instead of risk differences.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted: (i) to adjust for any variables with imbalance at baseline, (ii) to repeat the primary analysis based on participants whose primary outcome was available at 9 months and (iii) to investigate the effects of treatment adherence. Complier‐average causal effect analysis39 was conducted where taking ≥ 75% of expected treatments was considered a complier. Planned subgroup analyses were: (i) children vs. adults, (ii) by body region of the target vitiligo patch, (iii) by activity of the target patch (hypomelanotic patch: definitely vs. maybe or no) and (iv) ≥ 4 years duration of vitiligo vs. < 4 years. These analyses were conducted by inclusion of appropriate interaction terms in the regression model and were exploratory.

Secondary outcomes were analysed by a similar approach, using appropriate regression modelling depending on the outcome type. An additional post hoc subgroup analysis explored the impact of skin type (types I–III vs. types IV–VI).

Patient and public involvement

People with vitiligo were involved in all aspects of the trial, including prioritization of the research questions, study design, oversight, and conduct and interpretation of the results.32

Data sharing

Anonymized patient‐level data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Recruitment and participant characteristics

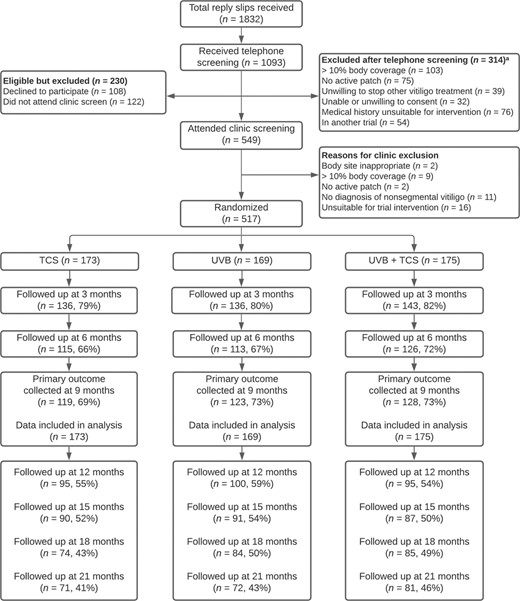

Recruitment was from 3 July 2015 to 1 September 2017, with 517 participants randomized (398 adults and 119 children). Primary outcome data were available for 370 (72%) participants (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics were well balanced across treatment groups (Table 1).

CONSORT flow diagram. Reasons for noncollection of primary outcome data at 9 months were: not assessed in clinic (n = 4), withdrew consent (n = 60), discontinued due to adverse effects (n = 3), lost to follow‐up (n = 75) and other (n = 5). These reasons were similarly distributed within each treatment arm. Of those who withdrew consent, 11 stated that this was due to lack of treatment response and 33 due to time burden. Of those lost to follow‐up, one stated that this was due to lack of treatment response and two due to time burden. TCS, topical corticosteroid; UVB, ultraviolet B. aPatients could have more than one reason for exclusion

| Characteristic | TCS (n = 173) | NB‐UVB (n = 169) | Combination (n = 175) |

| Age at randomization (years), mean (SD) | 38·6 (20·0) | 36·9 (18·9) | 37·0 (19·1) |

| Age of adults at randomization (years), mean (SD); n | 46·7 (15·2); 133 | 44·7 (14·0); 130 | 44·8 (14·2); 135 |

| Age of children at randomization (years), mean (SD); n | 11·7 (3·7); 40 | 10·8 (3·5); 39 | 10·6 (3·3); 40 |

| Sex male | 75 (43) | 88 (52) | 105 (60) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 112 (65) | 114 (67) | 104 (59) |

| Indian | 13 (8) | 13 (8) | 10 (6) |

| Pakistani | 12 (7) | 15 (9) | 27 (15) |

| Bangladeshi | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Black | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 7 (4) |

| Chinese | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Other Asian (not Chinese) | 5 (3) | 6 (4) | 6 (3) |

| Mixed race | 9 (5) | 6 (4) | 6 (3) |

| Other | 10 (6) | 7 (4) | 9 (5) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Source of recruitment | |||

| Primary care | 35 (20) | 36 (21) | 47 (27) |

| Secondary care | 74 (43) | 67 (40) | 72 (41) |

| Self‐referral | 64 (37) | 66 (39) | 56 (32) |

| Skin phototype | |||

| I | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 5 (3) |

| II | 31 (18) | 32 (19) | 29 (17) |

| III | 70 (40) | 66 (39) | 59 (34) |

| IV | 29 (17) | 34 (20) | 33 (19) |

| V | 35 (20) | 25 (15) | 44 (25) |

| VI | 6 (3) | 10 (6) | 5 (3) |

| Medical history | |||

| Type I diabetes | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | 6 (3) |

| Hypothyroidism | 21 (12) | 18 (11) | 10 (6) |

| Addison disease | 2 (1) | 0 | 3 (2) |

| Pernicious anaemia | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 6 (3) |

| Alopecia areata | 3 (2) | 7 (4) | 3 (2) |

| Duration of vitiligo (years), median (interquartile range) | 7 (3–16) | 5 (3–11) | 7 (4–15) |

| Previous treatments used for vitiligo | |||

| Light therapy | 28 (16) | 26 (15) | 37 (21) |

| Corticosteroid cream or ointment | 80 (46) | 75 (44) | 80 (46) |

| Calcineurin inhibitor cream or ointment | 51 (29) | 39 (23) | 56 (32) |

| Cosmetic camouflage | 45 (26) | 44 (26) | 40 (23) |

| Other | 20 (12) | 15 (9) | 17 (10) |

| Target patch location | |||

| Head and neck | 53 (31) | 52 (31) | 56 (32) |

| Hands and feet | 56 (32) | 53 (31) | 55 (31) |

| Rest of the body | 64 (37) | 64 (38) | 64 (37) |

| Number of assessed patches | |||

| 1 | 50 (29) | 50 (30) | 62 (35) |

| 2 | 74 (43) | 77 (46) | 73 (42) |

| 3 | 49 (28) | 42 (25) | 40 (23) |

| Target patch hypomelanotica | |||

| Definitely | 52 (30) | 46 (27) | 52 (30) |

| Maybe or no | 121 (70) | 123 (73) | 123 (70) |

| Characteristic | TCS (n = 173) | NB‐UVB (n = 169) | Combination (n = 175) |

| Age at randomization (years), mean (SD) | 38·6 (20·0) | 36·9 (18·9) | 37·0 (19·1) |

| Age of adults at randomization (years), mean (SD); n | 46·7 (15·2); 133 | 44·7 (14·0); 130 | 44·8 (14·2); 135 |

| Age of children at randomization (years), mean (SD); n | 11·7 (3·7); 40 | 10·8 (3·5); 39 | 10·6 (3·3); 40 |

| Sex male | 75 (43) | 88 (52) | 105 (60) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 112 (65) | 114 (67) | 104 (59) |

| Indian | 13 (8) | 13 (8) | 10 (6) |

| Pakistani | 12 (7) | 15 (9) | 27 (15) |

| Bangladeshi | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Black | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 7 (4) |

| Chinese | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Other Asian (not Chinese) | 5 (3) | 6 (4) | 6 (3) |

| Mixed race | 9 (5) | 6 (4) | 6 (3) |

| Other | 10 (6) | 7 (4) | 9 (5) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Source of recruitment | |||

| Primary care | 35 (20) | 36 (21) | 47 (27) |

| Secondary care | 74 (43) | 67 (40) | 72 (41) |

| Self‐referral | 64 (37) | 66 (39) | 56 (32) |

| Skin phototype | |||

| I | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 5 (3) |

| II | 31 (18) | 32 (19) | 29 (17) |

| III | 70 (40) | 66 (39) | 59 (34) |

| IV | 29 (17) | 34 (20) | 33 (19) |

| V | 35 (20) | 25 (15) | 44 (25) |

| VI | 6 (3) | 10 (6) | 5 (3) |

| Medical history | |||

| Type I diabetes | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | 6 (3) |

| Hypothyroidism | 21 (12) | 18 (11) | 10 (6) |

| Addison disease | 2 (1) | 0 | 3 (2) |

| Pernicious anaemia | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 6 (3) |

| Alopecia areata | 3 (2) | 7 (4) | 3 (2) |

| Duration of vitiligo (years), median (interquartile range) | 7 (3–16) | 5 (3–11) | 7 (4–15) |

| Previous treatments used for vitiligo | |||

| Light therapy | 28 (16) | 26 (15) | 37 (21) |

| Corticosteroid cream or ointment | 80 (46) | 75 (44) | 80 (46) |

| Calcineurin inhibitor cream or ointment | 51 (29) | 39 (23) | 56 (32) |

| Cosmetic camouflage | 45 (26) | 44 (26) | 40 (23) |

| Other | 20 (12) | 15 (9) | 17 (10) |

| Target patch location | |||

| Head and neck | 53 (31) | 52 (31) | 56 (32) |

| Hands and feet | 56 (32) | 53 (31) | 55 (31) |

| Rest of the body | 64 (37) | 64 (38) | 64 (37) |

| Number of assessed patches | |||

| 1 | 50 (29) | 50 (30) | 62 (35) |

| 2 | 74 (43) | 77 (46) | 73 (42) |

| 3 | 49 (28) | 42 (25) | 40 (23) |

| Target patch hypomelanotica | |||

| Definitely | 52 (30) | 46 (27) | 52 (30) |

| Maybe or no | 121 (70) | 123 (73) | 123 (70) |

| Characteristic | TCS (n = 173) | NB‐UVB (n = 169) | Combination (n = 175) |

| Age at randomization (years), mean (SD) | 38·6 (20·0) | 36·9 (18·9) | 37·0 (19·1) |

| Age of adults at randomization (years), mean (SD); n | 46·7 (15·2); 133 | 44·7 (14·0); 130 | 44·8 (14·2); 135 |

| Age of children at randomization (years), mean (SD); n | 11·7 (3·7); 40 | 10·8 (3·5); 39 | 10·6 (3·3); 40 |

| Sex male | 75 (43) | 88 (52) | 105 (60) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 112 (65) | 114 (67) | 104 (59) |

| Indian | 13 (8) | 13 (8) | 10 (6) |

| Pakistani | 12 (7) | 15 (9) | 27 (15) |

| Bangladeshi | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Black | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 7 (4) |

| Chinese | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Other Asian (not Chinese) | 5 (3) | 6 (4) | 6 (3) |

| Mixed race | 9 (5) | 6 (4) | 6 (3) |

| Other | 10 (6) | 7 (4) | 9 (5) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Source of recruitment | |||

| Primary care | 35 (20) | 36 (21) | 47 (27) |

| Secondary care | 74 (43) | 67 (40) | 72 (41) |

| Self‐referral | 64 (37) | 66 (39) | 56 (32) |

| Skin phototype | |||

| I | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 5 (3) |

| II | 31 (18) | 32 (19) | 29 (17) |

| III | 70 (40) | 66 (39) | 59 (34) |

| IV | 29 (17) | 34 (20) | 33 (19) |

| V | 35 (20) | 25 (15) | 44 (25) |

| VI | 6 (3) | 10 (6) | 5 (3) |

| Medical history | |||

| Type I diabetes | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | 6 (3) |

| Hypothyroidism | 21 (12) | 18 (11) | 10 (6) |

| Addison disease | 2 (1) | 0 | 3 (2) |

| Pernicious anaemia | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 6 (3) |

| Alopecia areata | 3 (2) | 7 (4) | 3 (2) |

| Duration of vitiligo (years), median (interquartile range) | 7 (3–16) | 5 (3–11) | 7 (4–15) |

| Previous treatments used for vitiligo | |||

| Light therapy | 28 (16) | 26 (15) | 37 (21) |

| Corticosteroid cream or ointment | 80 (46) | 75 (44) | 80 (46) |

| Calcineurin inhibitor cream or ointment | 51 (29) | 39 (23) | 56 (32) |

| Cosmetic camouflage | 45 (26) | 44 (26) | 40 (23) |

| Other | 20 (12) | 15 (9) | 17 (10) |

| Target patch location | |||

| Head and neck | 53 (31) | 52 (31) | 56 (32) |

| Hands and feet | 56 (32) | 53 (31) | 55 (31) |

| Rest of the body | 64 (37) | 64 (38) | 64 (37) |

| Number of assessed patches | |||

| 1 | 50 (29) | 50 (30) | 62 (35) |

| 2 | 74 (43) | 77 (46) | 73 (42) |

| 3 | 49 (28) | 42 (25) | 40 (23) |

| Target patch hypomelanotica | |||

| Definitely | 52 (30) | 46 (27) | 52 (30) |

| Maybe or no | 121 (70) | 123 (73) | 123 (70) |

| Characteristic | TCS (n = 173) | NB‐UVB (n = 169) | Combination (n = 175) |

| Age at randomization (years), mean (SD) | 38·6 (20·0) | 36·9 (18·9) | 37·0 (19·1) |

| Age of adults at randomization (years), mean (SD); n | 46·7 (15·2); 133 | 44·7 (14·0); 130 | 44·8 (14·2); 135 |

| Age of children at randomization (years), mean (SD); n | 11·7 (3·7); 40 | 10·8 (3·5); 39 | 10·6 (3·3); 40 |

| Sex male | 75 (43) | 88 (52) | 105 (60) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 112 (65) | 114 (67) | 104 (59) |

| Indian | 13 (8) | 13 (8) | 10 (6) |

| Pakistani | 12 (7) | 15 (9) | 27 (15) |

| Bangladeshi | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Black | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 7 (4) |

| Chinese | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Other Asian (not Chinese) | 5 (3) | 6 (4) | 6 (3) |

| Mixed race | 9 (5) | 6 (4) | 6 (3) |

| Other | 10 (6) | 7 (4) | 9 (5) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Source of recruitment | |||

| Primary care | 35 (20) | 36 (21) | 47 (27) |

| Secondary care | 74 (43) | 67 (40) | 72 (41) |

| Self‐referral | 64 (37) | 66 (39) | 56 (32) |

| Skin phototype | |||

| I | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 5 (3) |

| II | 31 (18) | 32 (19) | 29 (17) |

| III | 70 (40) | 66 (39) | 59 (34) |

| IV | 29 (17) | 34 (20) | 33 (19) |

| V | 35 (20) | 25 (15) | 44 (25) |

| VI | 6 (3) | 10 (6) | 5 (3) |

| Medical history | |||

| Type I diabetes | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | 6 (3) |

| Hypothyroidism | 21 (12) | 18 (11) | 10 (6) |

| Addison disease | 2 (1) | 0 | 3 (2) |

| Pernicious anaemia | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 6 (3) |

| Alopecia areata | 3 (2) | 7 (4) | 3 (2) |

| Duration of vitiligo (years), median (interquartile range) | 7 (3–16) | 5 (3–11) | 7 (4–15) |

| Previous treatments used for vitiligo | |||

| Light therapy | 28 (16) | 26 (15) | 37 (21) |

| Corticosteroid cream or ointment | 80 (46) | 75 (44) | 80 (46) |

| Calcineurin inhibitor cream or ointment | 51 (29) | 39 (23) | 56 (32) |

| Cosmetic camouflage | 45 (26) | 44 (26) | 40 (23) |

| Other | 20 (12) | 15 (9) | 17 (10) |

| Target patch location | |||

| Head and neck | 53 (31) | 52 (31) | 56 (32) |

| Hands and feet | 56 (32) | 53 (31) | 55 (31) |

| Rest of the body | 64 (37) | 64 (38) | 64 (37) |

| Number of assessed patches | |||

| 1 | 50 (29) | 50 (30) | 62 (35) |

| 2 | 74 (43) | 77 (46) | 73 (42) |

| 3 | 49 (28) | 42 (25) | 40 (23) |

| Target patch hypomelanotica | |||

| Definitely | 52 (30) | 46 (27) | 52 (30) |

| Maybe or no | 121 (70) | 123 (73) | 123 (70) |

Adherence

The median percentage of NB‐UVB treatment days (actual/allocated) was 81% for TCS, 77% for NB‐UVB and 74% for the combination, and for ointment 79% for TCS, 83% for NB‐UVB and 77% for combination. Just under half of participants used the treatments for > 75% of the expected duration (Table S2; see Supporting Information). Assuming 100% adherence, and a participant with a skin type requiring dose escalation to the maximum dose in the treatment schedule, we estimate the maximum possible total dose of NB‐UVB received over the 9‐month treatment period to be 4 mW cm−2 × 822 s × 135 treatment sessions = 443·9 mJ cm−2.

In addition to written and online video training,32 participants received face‐to‐face training (mean 70 min) prior to using the treatments at home. For participants using active light devices, the median time taken to administer the treatment was approximately 20 min, including time for set‐up, administering the light, and documenting timings and side‐effects in the treatment diary.

Difficulties in using the treatments are summarized in Table S2 (see Supporting Information). Burden of treatment was identified as an issue by 42 of 142 (30%) in the TCS group, 38 of 140 (27%) in the NB‐UVB group and 36 of 149 (24%) in the combination group, although interpretation is difficult as all three groups used both treatments throughout (either active or dummy/placebo). Overall, NB‐UVB treatment was reported to be more burdensome than treatment with TCS. Burden of treatment and side‐effects were the most commonly cited difficulties for both groups and were common reasons for discontinuation of treatment, along with lack of treatment response.

Blinding

At the 9‐month visit, investigators reported possible unblinding for 21%, 28% and 27% of participants in the TCS, NB‐UVB and combination groups, respectively. More participants reported possible unblinding (39%, 55% and 44% in the TCS, NB‐UVB and combination groups, respectively), supporting the need for confirmation of the primary outcome using blinded outcome assessment.

Primary outcome

The proportions of participants who reported treatment success (a lot less noticeable or no longer noticeable) at 9 months were 20 of 119 (17%) for TCS, 27 of 123 (22%) for NB‐UVB and 34 of 128 (27%) for combination treatment (Table 2). Combination treatment was superior to TCS: adjusted between‐group difference 10·9% (95% CI 1·0–20·9%; P = 0·032; number needed to treat = 10). NB‐UVB alone was not superior to TCS: adjusted between‐group difference 5·2% (95% CI − 4·4% to 14·9%; P = 0·29; number needed to treat = 19) (Table 3). The proportions of participants achieving treatment success at each timepoint are shown in Figure S1 (see Supporting Information).

| TCS (n = 173) | NB‐UVB (n = 169) | Combination (n = 175) | |

| Patient response to VNS at 3 months | |||

| More noticeable | 16 (12) | 26 (19) | 15 (10) |

| As noticeable | 70 (52) | 57 (42) | 62 (43) |

| Slightly less noticeable | 34 (25) | 34 (25) | 47 (33) |

| A lot less noticeable | 13 (10) | 19 (14) | 17 (12) |

| No longer noticeable | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Patient response to VNS at 6 months | |||

| More noticeable | 11 (10) | 23 (20) | 10 (8) |

| As noticeable | 51 (44) | 37 (33) | 36 (29) |

| Slightly less noticeable | 37 (32) | 33 (29) | 45 (36) |

| A lot less noticeable | 14 (12) | 18 (16) | 28 (22) |

| No longer noticeable | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 7 (6) |

| Participants with primary outcome data at 9 months | 119 (69) | 123 (73) | 128 (73) |

| Patient response to VNS at 9 months | |||

| More noticeable | 18 (15) | 27 (22) | 17 (13) |

| As noticeable | 53 (45) | 33 (27) | 32 (25) |

| Slightly less noticeable | 28 (24) | 36 (29) | 45 (35) |

| A lot less noticeable | 15 (13) | 25 (20) | 27 (21) |

| No longer noticeable | 5 (4) | 2 (2) | 7 (5) |

| Patient‐reported treatment successa using VNS at 9 months | 20 (17) | 27 (22) | 34 (27) |

| TCS (n = 173) | NB‐UVB (n = 169) | Combination (n = 175) | |

| Patient response to VNS at 3 months | |||

| More noticeable | 16 (12) | 26 (19) | 15 (10) |

| As noticeable | 70 (52) | 57 (42) | 62 (43) |

| Slightly less noticeable | 34 (25) | 34 (25) | 47 (33) |

| A lot less noticeable | 13 (10) | 19 (14) | 17 (12) |

| No longer noticeable | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Patient response to VNS at 6 months | |||

| More noticeable | 11 (10) | 23 (20) | 10 (8) |

| As noticeable | 51 (44) | 37 (33) | 36 (29) |

| Slightly less noticeable | 37 (32) | 33 (29) | 45 (36) |

| A lot less noticeable | 14 (12) | 18 (16) | 28 (22) |

| No longer noticeable | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 7 (6) |

| Participants with primary outcome data at 9 months | 119 (69) | 123 (73) | 128 (73) |

| Patient response to VNS at 9 months | |||

| More noticeable | 18 (15) | 27 (22) | 17 (13) |

| As noticeable | 53 (45) | 33 (27) | 32 (25) |

| Slightly less noticeable | 28 (24) | 36 (29) | 45 (35) |

| A lot less noticeable | 15 (13) | 25 (20) | 27 (21) |

| No longer noticeable | 5 (4) | 2 (2) | 7 (5) |

| Patient‐reported treatment successa using VNS at 9 months | 20 (17) | 27 (22) | 34 (27) |

| TCS (n = 173) | NB‐UVB (n = 169) | Combination (n = 175) | |

| Patient response to VNS at 3 months | |||

| More noticeable | 16 (12) | 26 (19) | 15 (10) |

| As noticeable | 70 (52) | 57 (42) | 62 (43) |

| Slightly less noticeable | 34 (25) | 34 (25) | 47 (33) |

| A lot less noticeable | 13 (10) | 19 (14) | 17 (12) |

| No longer noticeable | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Patient response to VNS at 6 months | |||

| More noticeable | 11 (10) | 23 (20) | 10 (8) |

| As noticeable | 51 (44) | 37 (33) | 36 (29) |

| Slightly less noticeable | 37 (32) | 33 (29) | 45 (36) |

| A lot less noticeable | 14 (12) | 18 (16) | 28 (22) |

| No longer noticeable | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 7 (6) |

| Participants with primary outcome data at 9 months | 119 (69) | 123 (73) | 128 (73) |

| Patient response to VNS at 9 months | |||

| More noticeable | 18 (15) | 27 (22) | 17 (13) |

| As noticeable | 53 (45) | 33 (27) | 32 (25) |

| Slightly less noticeable | 28 (24) | 36 (29) | 45 (35) |

| A lot less noticeable | 15 (13) | 25 (20) | 27 (21) |

| No longer noticeable | 5 (4) | 2 (2) | 7 (5) |

| Patient‐reported treatment successa using VNS at 9 months | 20 (17) | 27 (22) | 34 (27) |

| TCS (n = 173) | NB‐UVB (n = 169) | Combination (n = 175) | |

| Patient response to VNS at 3 months | |||

| More noticeable | 16 (12) | 26 (19) | 15 (10) |

| As noticeable | 70 (52) | 57 (42) | 62 (43) |

| Slightly less noticeable | 34 (25) | 34 (25) | 47 (33) |

| A lot less noticeable | 13 (10) | 19 (14) | 17 (12) |

| No longer noticeable | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Patient response to VNS at 6 months | |||

| More noticeable | 11 (10) | 23 (20) | 10 (8) |

| As noticeable | 51 (44) | 37 (33) | 36 (29) |

| Slightly less noticeable | 37 (32) | 33 (29) | 45 (36) |

| A lot less noticeable | 14 (12) | 18 (16) | 28 (22) |

| No longer noticeable | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 7 (6) |

| Participants with primary outcome data at 9 months | 119 (69) | 123 (73) | 128 (73) |

| Patient response to VNS at 9 months | |||

| More noticeable | 18 (15) | 27 (22) | 17 (13) |

| As noticeable | 53 (45) | 33 (27) | 32 (25) |

| Slightly less noticeable | 28 (24) | 36 (29) | 45 (35) |

| A lot less noticeable | 15 (13) | 25 (20) | 27 (21) |

| No longer noticeable | 5 (4) | 2 (2) | 7 (5) |

| Patient‐reported treatment successa using VNS at 9 months | 20 (17) | 27 (22) | 34 (27) |

| Treatment, % (n/N) | Patient‐reported treatment success using VNS at 9 months | |

| Topical corticosteroid (TCS) | 17% (20/119) | |

| Narrowband ultraviolet B (NB‐UVB) | 22% (27/123) | |

| Combination | 27% (34/128) | |

| Between‐group comparisonb | ||

| NB‐UVB vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 5·20% (−4·45 to 14·9) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 1·44 (0·77 to 2·70) | |

| Combination vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 10·9% (0·97 to 20·9) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 1·93 (1·02 to 3·68) | |

| Treatment, % (n/N) | Patient‐reported treatment success using VNS at 9 months | |

| Topical corticosteroid (TCS) | 17% (20/119) | |

| Narrowband ultraviolet B (NB‐UVB) | 22% (27/123) | |

| Combination | 27% (34/128) | |

| Between‐group comparisonb | ||

| NB‐UVB vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 5·20% (−4·45 to 14·9) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 1·44 (0·77 to 2·70) | |

| Combination vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 10·9% (0·97 to 20·9) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 1·93 (1·02 to 3·68) | |

| Treatment, % (n/N) | Patient‐reported treatment success using VNS at 9 months | |

| Topical corticosteroid (TCS) | 17% (20/119) | |

| Narrowband ultraviolet B (NB‐UVB) | 22% (27/123) | |

| Combination | 27% (34/128) | |

| Between‐group comparisonb | ||

| NB‐UVB vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 5·20% (−4·45 to 14·9) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 1·44 (0·77 to 2·70) | |

| Combination vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 10·9% (0·97 to 20·9) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 1·93 (1·02 to 3·68) | |

| Treatment, % (n/N) | Patient‐reported treatment success using VNS at 9 months | |

| Topical corticosteroid (TCS) | 17% (20/119) | |

| Narrowband ultraviolet B (NB‐UVB) | 22% (27/123) | |

| Combination | 27% (34/128) | |

| Between‐group comparisonb | ||

| NB‐UVB vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 5·20% (−4·45 to 14·9) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 1·44 (0·77 to 2·70) | |

| Combination vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 10·9% (0·97 to 20·9) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 1·93 (1·02 to 3·68) | |

All sensitivity analyses were consistent with the primary analysis. Treatment effects were largest among participants who adhered to the interventions ≥ 75% of the time (Figure S2; see Supporting Information).

There was no evidence that any of the treatments were more effective than others for any of the predefined subgroups (Table S3; see Supporting Information). Post hoc exploration of treatment response by skin type (types I–III vs. types IV–VI) also found no differences between the groups (Table S3).

Secondary outcomes

Treatment success using digital images, assessed by people with vitiligo who did not participate in the trial, was consistent with the primary analysis but suggested greater treatment effects than trial participants’ VNS assessments (Table 4).

Secondary outcome: treatment success by blinded patient and public involvement (PPI) assessors (Vitiligo Noticeability Scale using digital images at baseline and 9 months)

| Treatment, % (n/N) | Treatment success by blinded PPI assessors at 9 months (target patch) | |

| Topical corticosteroid (TCS) | 11% (12/112) | |

| Narrowband ultraviolet B (NB‐UVB) | 20% (22/108) | |

| Combination | 28% (32/116) | |

| Between‐group comparisona | ||

| NB‐UVB vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 9·70% (1·23–18·2) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 2·22 (1·14–4·31) | |

| Combination vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 16·3% (7·02–25·6) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 3·52 (1·80–6·89) | |

| Treatment, % (n/N) | Treatment success by blinded PPI assessors at 9 months (target patch) | |

| Topical corticosteroid (TCS) | 11% (12/112) | |

| Narrowband ultraviolet B (NB‐UVB) | 20% (22/108) | |

| Combination | 28% (32/116) | |

| Between‐group comparisona | ||

| NB‐UVB vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 9·70% (1·23–18·2) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 2·22 (1·14–4·31) | |

| Combination vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 16·3% (7·02–25·6) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 3·52 (1·80–6·89) | |

Secondary outcome: treatment success by blinded patient and public involvement (PPI) assessors (Vitiligo Noticeability Scale using digital images at baseline and 9 months)

| Treatment, % (n/N) | Treatment success by blinded PPI assessors at 9 months (target patch) | |

| Topical corticosteroid (TCS) | 11% (12/112) | |

| Narrowband ultraviolet B (NB‐UVB) | 20% (22/108) | |

| Combination | 28% (32/116) | |

| Between‐group comparisona | ||

| NB‐UVB vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 9·70% (1·23–18·2) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 2·22 (1·14–4·31) | |

| Combination vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 16·3% (7·02–25·6) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 3·52 (1·80–6·89) | |

| Treatment, % (n/N) | Treatment success by blinded PPI assessors at 9 months (target patch) | |

| Topical corticosteroid (TCS) | 11% (12/112) | |

| Narrowband ultraviolet B (NB‐UVB) | 20% (22/108) | |

| Combination | 28% (32/116) | |

| Between‐group comparisona | ||

| NB‐UVB vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 9·70% (1·23–18·2) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 2·22 (1·14–4·31) | |

| Combination vs. TCS | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI) | 16·3% (7·02–25·6) |

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | 3·52 (1·80–6·89) | |

Participant‐reported treatment success at 9 months (all assessed patches) was lower for patches on the hands and feet than on other body regions. However, the relative effectiveness of the three treatment groups remained similar in different body regions (Figure S3 and Table S4; see Supporting Information).

Most participants had onset of treatment response by 3 months, defined as the target patch having improved or stayed the same (Figure S4; see Supporting Information), with 40% in TCS, 61% in NB‐UVB and 60% in the combination group showing improvement in their vitiligo (that is, more than stopped spreading).

Treatment success, defined as ≥ 75% repigmentation, supported the finding that combination treatment was superior to TCS alone, but NB‐UVB alone was not superior to TCS: this occurred in four patients (3%) for TCS, nine (8%) for NB‐UVB and 18 (15%) for combination. This gives an adjusted odds ratio of 4·62 (95% CI 1·50–14·2) for combination compared with TCS, and 2·22 (95% CI 0·66–7·51) for NB‐UVB compared with TCS (Table 5).

Secondary outcome: percentage repigmentation assessed by blinded dermatologist and investigators

| TCS | NB‐UVB | Combination | |

| Repigmentation: treatment success at 9 months assessed by blinded dermatologist using digital images of target patch | 3% (4/115) | 8% (9/116) | 15% (18/120) |

| Repigmentation treatment success assessed by investigators (target patch) at: | |||

| 3 months | 3% (4/134) | 4% (6/136) | 4% (6/143) |

| 6 months | 7% (8/115) | 5% (6/113) | 11% (14/125) |

| 9 months | 9% (10/134) | 10% (11/136) | 18% (21/143) |

| Between‐group comparison | Adjusted odds ratioa | 95% confidence interval | |

| NB‐UVB vs. TCS | 2·22 | 0·66–7·51 | |

| Combination vs. TCS | 4·62 | 1·50–14·2 | |

| TCS | NB‐UVB | Combination | |

| Repigmentation: treatment success at 9 months assessed by blinded dermatologist using digital images of target patch | 3% (4/115) | 8% (9/116) | 15% (18/120) |

| Repigmentation treatment success assessed by investigators (target patch) at: | |||

| 3 months | 3% (4/134) | 4% (6/136) | 4% (6/143) |

| 6 months | 7% (8/115) | 5% (6/113) | 11% (14/125) |

| 9 months | 9% (10/134) | 10% (11/136) | 18% (21/143) |

| Between‐group comparison | Adjusted odds ratioa | 95% confidence interval | |

| NB‐UVB vs. TCS | 2·22 | 0·66–7·51 | |

| Combination vs. TCS | 4·62 | 1·50–14·2 | |

Secondary outcome: percentage repigmentation assessed by blinded dermatologist and investigators

| TCS | NB‐UVB | Combination | |

| Repigmentation: treatment success at 9 months assessed by blinded dermatologist using digital images of target patch | 3% (4/115) | 8% (9/116) | 15% (18/120) |

| Repigmentation treatment success assessed by investigators (target patch) at: | |||

| 3 months | 3% (4/134) | 4% (6/136) | 4% (6/143) |

| 6 months | 7% (8/115) | 5% (6/113) | 11% (14/125) |

| 9 months | 9% (10/134) | 10% (11/136) | 18% (21/143) |

| Between‐group comparison | Adjusted odds ratioa | 95% confidence interval | |

| NB‐UVB vs. TCS | 2·22 | 0·66–7·51 | |

| Combination vs. TCS | 4·62 | 1·50–14·2 | |

| TCS | NB‐UVB | Combination | |

| Repigmentation: treatment success at 9 months assessed by blinded dermatologist using digital images of target patch | 3% (4/115) | 8% (9/116) | 15% (18/120) |

| Repigmentation treatment success assessed by investigators (target patch) at: | |||

| 3 months | 3% (4/134) | 4% (6/136) | 4% (6/143) |

| 6 months | 7% (8/115) | 5% (6/113) | 11% (14/125) |

| 9 months | 9% (10/134) | 10% (11/136) | 18% (21/143) |

| Between‐group comparison | Adjusted odds ratioa | 95% confidence interval | |

| NB‐UVB vs. TCS | 2·22 | 0·66–7·51 | |

| Combination vs. TCS | 4·62 | 1·50–14·2 | |

Long‐term follow‐up

The percentages of participants followed up at 12, 15, 18 and 21 months after randomization were 56%, 52%, 47% and 43%, respectively. VNS scores throughout the 21‐month study period are shown in Figure S1 (see Supporting Information). During the follow‐up phase, > 40% of participants reported loss of treatment response by 21 months, across all groups (Table S5; see Supporting Information). Both generic and vitiligo‐specific quality‐of‐life scores were similar at follow‐up across the treatment groups (Table S6; see Supporting Information).

Safety

In total 124 (25%) participants reported 206 treatment‐related adverse events: 33 events from 24 participants (14%) in the TCS group, 69 events from 48 participants (28%) in the NB‐UVB group and 104 from 52 participants (30%) in the combination group (Table 6). There were five serious adverse events reported from five participants, but none was related to a trial intervention.

| TCS (n = 173) | NB‐UVB (n = 169) | Combination (n = 175) | |

| Total number of participants reporting any related AEs | 24 (14%) | 48 (28%) | 52 (30%) |

| Total number of reported related AEs | 33 | 69 | 104 |

| AEs by severity | |||

| Mild | 30 | 32 | 58 |

| Moderate | 3 | 24 | 40 |

| Severe | 0 | 13 | 6 |

| AEs by outcome | |||

| Recovered | 20 | 53 | 92 |

| Resolved with sequelae | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| Ongoing | 7 | 5 | 6 |

| Unknown | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| Number of erythema events in adults | 2 (2)a | 22 (20)a | 37 (26)a |

| Grade 3 erythema | 0 | 8 | 33 |

| Grade 4 erythema | 2 | 14 | 4 |

| Number of erythema events in children | 1 (1)a | 7 (6)a | 8 (7)a |

| Grade 3 erythema | 1 | 6 | 8 |

| Grade 4 erythema | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Erythema events by outcome | 3 | 29 | 45 |

| Recovered | 3 | 25 | 44 |

| Resolved with sequelae | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Ongoing | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Unknown | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Number of skin thinningb events in adults | 5 (5)a | 2 (2)a | 5 (5)a |

| Number of skin thinningb events in children | 1 (1)a | 0 | 0 |

| Skin thinningb events by outcome | 6 | 2 | 5 |

| Recovered | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Resolved with sequelae | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Ongoing | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| TCS (n = 173) | NB‐UVB (n = 169) | Combination (n = 175) | |

| Total number of participants reporting any related AEs | 24 (14%) | 48 (28%) | 52 (30%) |

| Total number of reported related AEs | 33 | 69 | 104 |

| AEs by severity | |||

| Mild | 30 | 32 | 58 |

| Moderate | 3 | 24 | 40 |

| Severe | 0 | 13 | 6 |

| AEs by outcome | |||

| Recovered | 20 | 53 | 92 |

| Resolved with sequelae | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| Ongoing | 7 | 5 | 6 |

| Unknown | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| Number of erythema events in adults | 2 (2)a | 22 (20)a | 37 (26)a |

| Grade 3 erythema | 0 | 8 | 33 |

| Grade 4 erythema | 2 | 14 | 4 |

| Number of erythema events in children | 1 (1)a | 7 (6)a | 8 (7)a |

| Grade 3 erythema | 1 | 6 | 8 |

| Grade 4 erythema | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Erythema events by outcome | 3 | 29 | 45 |

| Recovered | 3 | 25 | 44 |

| Resolved with sequelae | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Ongoing | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Unknown | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Number of skin thinningb events in adults | 5 (5)a | 2 (2)a | 5 (5)a |

| Number of skin thinningb events in children | 1 (1)a | 0 | 0 |

| Skin thinningb events by outcome | 6 | 2 | 5 |

| Recovered | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Resolved with sequelae | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Ongoing | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| TCS (n = 173) | NB‐UVB (n = 169) | Combination (n = 175) | |

| Total number of participants reporting any related AEs | 24 (14%) | 48 (28%) | 52 (30%) |

| Total number of reported related AEs | 33 | 69 | 104 |

| AEs by severity | |||

| Mild | 30 | 32 | 58 |

| Moderate | 3 | 24 | 40 |

| Severe | 0 | 13 | 6 |

| AEs by outcome | |||

| Recovered | 20 | 53 | 92 |

| Resolved with sequelae | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| Ongoing | 7 | 5 | 6 |

| Unknown | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| Number of erythema events in adults | 2 (2)a | 22 (20)a | 37 (26)a |

| Grade 3 erythema | 0 | 8 | 33 |

| Grade 4 erythema | 2 | 14 | 4 |

| Number of erythema events in children | 1 (1)a | 7 (6)a | 8 (7)a |

| Grade 3 erythema | 1 | 6 | 8 |

| Grade 4 erythema | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Erythema events by outcome | 3 | 29 | 45 |

| Recovered | 3 | 25 | 44 |

| Resolved with sequelae | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Ongoing | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Unknown | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Number of skin thinningb events in adults | 5 (5)a | 2 (2)a | 5 (5)a |

| Number of skin thinningb events in children | 1 (1)a | 0 | 0 |

| Skin thinningb events by outcome | 6 | 2 | 5 |

| Recovered | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Resolved with sequelae | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Ongoing | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| TCS (n = 173) | NB‐UVB (n = 169) | Combination (n = 175) | |

| Total number of participants reporting any related AEs | 24 (14%) | 48 (28%) | 52 (30%) |

| Total number of reported related AEs | 33 | 69 | 104 |

| AEs by severity | |||

| Mild | 30 | 32 | 58 |

| Moderate | 3 | 24 | 40 |

| Severe | 0 | 13 | 6 |

| AEs by outcome | |||

| Recovered | 20 | 53 | 92 |

| Resolved with sequelae | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| Ongoing | 7 | 5 | 6 |

| Unknown | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| Number of erythema events in adults | 2 (2)a | 22 (20)a | 37 (26)a |

| Grade 3 erythema | 0 | 8 | 33 |

| Grade 4 erythema | 2 | 14 | 4 |

| Number of erythema events in children | 1 (1)a | 7 (6)a | 8 (7)a |

| Grade 3 erythema | 1 | 6 | 8 |

| Grade 4 erythema | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Erythema events by outcome | 3 | 29 | 45 |

| Recovered | 3 | 25 | 44 |

| Resolved with sequelae | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Ongoing | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Unknown | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Number of skin thinningb events in adults | 5 (5)a | 2 (2)a | 5 (5)a |

| Number of skin thinningb events in children | 1 (1)a | 0 | 0 |

| Skin thinningb events by outcome | 6 | 2 | 5 |

| Recovered | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Resolved with sequelae | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Ongoing | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Details of adverse events of particular interest (grade 3 or 4 erythema and skin thinning) are shown in Table 6. Grade 3 and 4 erythemas constituted the majority of adverse events in the NB‐UVB and combination groups, and these erythemas accounted for the higher overall adverse event rates in these groups. Fewer adverse events were reported in children than in adults.

Discussion

The HI‐Light trial was a large, pragmatic trial of home interventions for people with active, limited vitiligo. Combination treatment with handheld NB‐UVB and potent TCS is likely to be superior to potent TCS alone (number needed to treat = 10), although the CIs around this result were quite wide. We did not find clear evidence that handheld NB‐UVB monotherapy was better than TCS monotherapy. Results for percentage repigmentation (the most commonly used outcome in vitiligo trials)40 were consistent with the participant‐reported primary outcome using the VNS.

Both interventions were well tolerated. Erythema (grade 3 or 4) was the most frequently observed adverse event, but these episodes were managed effectively and were limited to the small areas being treated. Given the large total number of NB‐UVB treatments given across these groups, we feel that this is an acceptable level of erythemas and it is not suggestive of a significant safety risk. The incidence of clinical skin thinning was very low despite the relatively long‐term intermittent use of potent TCS, including on the face.

All sensitivity analyses were supportive of the main findings and participants who adhered to the treatment regimen (≥ 75%) were more likely to achieve treatment success. There was no difference between the rates of success in the treatment groups that could be attributed to age, skin type or duration of vitiligo.

The number of participants achieving a treatment success with the trial interventions was low but consistent with findings from other trials. A meta‐analysis of studies assessing phototherapy (whole body, as opposed to handheld) for vitiligo41 reported that around 19% of patients achieved a ‘marked response’ (> 75% repigmentation) after 6 months of treatment with NB‐UVB monotherapy. Participants in our study achieved similar rates of treatment success, as measured using the VNS (18% for NB‐UVB, 28% for combination at 6 months). The better response rates for vitiligo on the head and neck seen in our study are also consistent with previous findings.41

There are no other studies that have compared a combination of NB‐UVB and mometasone furoate with mometasone furoate alone, so direct comparison with a combination of treatments is not possible. The participants in our study used mometasone furoate on alternate weeks for 9 months, which differs from other published studies.37 We used this alternate‐week regimen on the basis of feasibility work that suggested that this would be more acceptable than once‐daily application over a 9‐month treatment period.

The Cochrane systematic review of interventions for vitiligo37 identified a study comparing the combination of NB‐UVB and clobetasol propionate (a more potent TCS) with NB‐UVB alone. That study suggested that combination treatment might be more effective. However, the study was too small for the results to be conclusive; the relative risk ratio for achieving > 75% repigmentation was 1·38 (95% CI 0·71–2·68).42

Previous small studies of home‐based handheld phototherapy devices for vitiligo have demonstrated their safety;23, 24 our larger study confirms this. A recently published study of patients undergoing long‐term NB‐UVB treatment (mean number of treatments = 211) reported no increase in skin cancer risk, suggesting that treatment can safely be continued for longer periods than in our study, although most patients in the study of Momen and Sarkany had skin types IV–VI.43

This was a large, pragmatic trial that controlled for the most common causes of bias. The patient‐reported primary outcome ensured that treatment success reflected the views of participants, and was supported by blinded outcome assessment using digital images.

As found in other vitiligo trials,37 retention throughout the trial was challenging, with just over 70% of participants providing primary outcome data at 9 months, and < 50% providing secondary outcome data by 21 months. As loss to follow‐up was higher than originally anticipated, the trial lacked power to provide a high level of precision around the point estimates.

The most significant drop in the number of participants remaining in the trial was from baseline to the first follow‐up at 3 months. Many participants commented that the time burden was the main reason for them doing so. Participants who adhered to the treatment regimen ≥ 75% of the time were more likely to achieve treatment success. This requires a significant time commitment, which some participants found challenging. In clinical practice, following such a treatment regimen may not be feasible for some individuals.

This trial has good external validity as it was a large, pragmatic trial with few exclusions, although participants with widespread vitiligo were excluded. People with all skin types and of all ethnicities were included in the trial as this reflected the types of patients typically presenting for vitiligo treatment within the UK health service. We did not exclude participants with lighter skin types, as vitiligo can cause considerable distress in such people, as well as in those with darker skin types.44

For people with vitiligo requiring second‐line therapy, combination treatment with potent TCS and NB‐UVB may be helpful. Patients should be informed that only about one‐quarter of those seeking treatment are likely to achieve a substantial treatment response, that considerable time commitment is required, and that response is likely to be slow.

This trial found considerable output variation between individual NB‐UVB devices,32 which demonstrates the need for quality assurance testing prior to use. We would recommend that any member of the public purchasing such a device seek specialist dermatologist advice and quality assurance before use.

Safety data provide reassurance that mometasone furoate 0·1% used intermittently ‘one week on, one week off’ for up to 9 months is safe for both children and adults. This potent TCS was helpful in stopping the spread of active disease and was successful in one in six cases, supporting its use as first‐line therapy. Health economic analysis and a process evaluation study were conducted alongside this trial and are reported separately.32 Forty per cent of participants reported loss of treatment response after stopping treatments, therefore research into strategies to maintain treatment response is needed.

In conclusion, combination therapy with NB‐UVB and potent TCS is likely to result in improved treatment response compared with potent TCS alone, for people with localized nonsegmental vitiligo. Both treatments are relatively safe and well tolerated, but were only successful in around one‐quarter of participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those who supported and contributed to delivery of the HI‐Light Vitiligo Trial, including the NIHR Clinical Research Network for assistance in identifying recruitment sites and provision of research infrastructure and staff, and the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network (DCTN) for help in trial design and identifying recruiting sites. The UK DCTN is grateful to the British Association of Dermatologists and the University of Nottingham for financial support of the network. We are grateful to Dermfix Ltd (www.dermfix.uk) for providing the NB‐UVB devices and dummy devices at a reduced cost. Dermfix Ltd had no role in the design, conduct or analysis of the trial. Members of the Centre of Evidence Based Dermatology’s Patient Panel provided input into the trial design and conduct and dissemination of trial findings. Thanks also to the people who responded to the online surveys to inform the trial design. A full list of contributors is provided in Appendix S1 (see Supporting Information).

References

Author notes

Funding sources This study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment Programme (project reference 12/24/02). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. Support for this trial was provided through Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit, the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network and the NIHR Clinical Research Network. This paper represents a summary of the trial results. A full and detailed trial report will be published within the NIHR journal and copyright retained by the Crown.

Conflicts of interest All authors’ organizations received financial support from the trial funder in order to deliver the submitted work; no authors received any additional support from any organization for the submitted work; no authors reported financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no authors reported other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. J.R.I. is Editor‐in‐Chief of the BJD but had no role in the publisher’s review of the submitted work.

K.S.T. and J.M.B. are joint lead authors.

*Plain language summary available online