-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Susan D Renoe, An insider perspective on broader impacts, BioScience, Volume 75, Issue 3, March 2025, Pages 207–211, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biaf004

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

All proposals submitted to the US National Science Foundation are evaluated on their intellectual merit and their broader impacts. Intellectual merit refers to the potential of the research to move forward scientific research, and broader impacts refers to the potential of the project to benefit society. This article gives a brief history of the broader impacts criterion and suggestions for how to effectively address it.

All proposals submitted to the US National Science Foundation (NSF) are reviewed on their intellectual merit and broader impacts. Intellectual merit refers to the potential of the research to advance knowledge, and broader impacts refers to the potential of the project “to benefit society and contribute to… desired societal outcomes” (NSF 2024).

Often, intellectual merit is seen as the threshold criterion, and broader impacts as the tiebreaker criterion, meaning that “NSF will not fund anything that does not pass muster on criterion #1” (NSB 1997). This approach to merit review sought to address the fear that adding broader impacts to the process would result in a “decline of [the] NSF's standards of excellence” (NSB 1997).

The deficit approach (Simis et al. 2016) to the societal benefits of research in the NSF review process led to a lack of understanding on how to review broader impacts plans and how they fit in the overall evaluation of the proposal (NSB 2011). In 2011, the National Science Board (NSB) upheld intellectual merit and broader impacts as the gold standard for merit review and issued new guidance on applying the criteria: The “NSF should make clear its expectation that both criteria are important and should be given full consideration during the review and decision-making processes; each criterion is necessary, but neither is sufficient” (NSB 2011).

In response to the NSB (2011) merit review report, the NSF updated its Proposal and Awards Policies and Procedures Guide (PAPPG; NSF 2024), which currently includes the NSB guidance that both criteria are to be given full consideration in proposal review and which takes it a step further, saying, “proposers must fully address both criteria.”

The America Competes Reauthorization Act of 2010 (COMPETES; US Congress 2010) directed the NSF to apply a broader impacts review criterion and encouraged institutions of higher education to provide training and programming to support principal investigators (PIs) to achieve their broader impacts goals, as well as provide evidence of institutional support for those activities. Today, many institutions have broader impacts offices or at least personnel who support researchers in the development of their broader impacts plans. In addition, proposals are increasingly including, either in the body of the text or in the supplemental documents, evidence of institutional support for broader impacts, such as facilities statements about relevant offices or centers who partner with the researcher on their broader impacts plan. These are seen as adding value to the proposal.

In the last 14 years, since the COMPETES legislation and the 2011 NSB report, the broader impacts landscape has changed substantially. Broader impacts are less of an afterthought or tie-breaker criterion, and more and more researchers and institutions are building their broader impacts capacity and integrating it into their research ecosystems. The need to address the mandates laid out in COMPETES, the NSB report, and the NSF PAPPG led 80 people to convene at the University of Missouri in the spring of 2013 to share best practices and to discuss the future of broader impacts infrastructure. From that initial meeting, the National Alliance for Broader Impacts (NABI) was formed to identify and curate promising models, practices, and evaluation methods for the broader impacts community; to expand engagement in and support of the development of high-quality broader impacts activities by educating current and future faculty and researchers on effective broader impacts practices; to develop human resources necessary for sustained growth and increased diversity of the broader impacts community; and to promote cross-institutional collaboration on and dissemination of broader impacts programs, practices, models, materials, and resources.

In 2018, with support from NSF, NABI evolved into the Center for Advancing Research Impact in Society (ARIS, grant no. OIA-2334906), which exists to support the growing broader impacts community (more than 1800 members worldwide) and to provide resources and professional development for individuals, institutions, and organizations to thoughtfully and effectively address the broader impacts criterion. What follows are the current best practices for ideating, creating, implementing, and evaluating excellent broader impacts plans for NSF proposals.

As was mentioned earlier, broader impacts are the benefit to society of the project and a way to advance desired outcomes, such as broadening the participation of underrepresented groups in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), improving STEM education, increasing science literacy and public engagement, improving the well-being of individuals, diversifying the STEM workforce, increasing partnerships, improving national security, enhancing STEM policy, improving US economic competitiveness, and enhancing research infrastructure (NSF 2024). These benefits have their roots in COMPETES and the 2011 NSB Report. The NSF (2024) reminded us that the research itself can be the broader impact, that broader impact activities can be directly related to your research, and that broader impact activities can be supported by or complementary to your project. However, the best proposals feature an integration of the broader impacts and the intellectual merit.

Describing the direct societal impacts of the research is also an important part of a broader impacts statement; however, it is not enough to label that statement as your broader impacts and move on. Research on transformative research shows that “most researchers feel that they cannot predict [transformative research] in proposals,” and “typically, researchers… realized the transformative nature of their work during later research stages” (Gravem et al. 2017). Further research shows that “promise inflation” can be harmful to the researcher (Gravem et al. 2017). In fact, it is very possible that proposals that rest their broader impacts solely on transformative research “are unlikely to be reviewed favorably” (Hossenfelder 2012). Given this information, in addition to stating the potential societal benefit of your research, it is also advisable to think about the 10 suggested areas of societal benefit listed in the NSF PAPPG (see figure 1; NSF 2024) and how your proposal can address one or more.

There is no magic number of broader impact activities or areas of impact. There is no competitive advantage to including all 10 suggested areas in your proposal, and there is no specified number of activities that will get you funded. You should include the number of activities needed to meet the goals of your broader impacts plan. The scale of activities should match your budget, timeline, and personnel. Also, the 10 areas are just suggestions; they are not meant to be exclusive or prescriptive.

In regard to the merit review criteria, one of the elements panelists are asked to consider is “to what extent do the proposed activities suggest and explore creative, original, or potentially transformative concepts?” (NSF 2024). This has led to no shortage of discomfort for proposers and reviewers, because some reviewers are looking for something new or novel with each NSF proposal, and others are looking for broader impact activities that have a proven record of success; there is no guarantee of what kind of reviewer your proposal will receive. The same problem exists with intellectual merit for some of the reasons mentioned earlier.

In terms of broader impacts, it is fine for proposers to include existing programs in their broader impacts plans. In this instance, I counsel PIs to include a statement on what their project will bring to the existing program if funded. This helps the reviewers to see the benefit of leveraging an existing and effective program along with how the new funding will enhance it. It is also important for PIs who want to try something unconventional or novel in their broader impacts plan to cite the relevant literature to explain why this broader impact activity is a good fit for the project and the audience. I have seen this play out in many different situations—from the researchers who include existing programs and receive negative comments to the researchers who want to engage the public in new and exciting ways and also receive negative comments. This issue has been discussed by the current NSB–NSF Merit Review Commission, and I would be surprised if new guidance is not issued when the report comes out.

What counts as broader impacts?

What do broader impact activities look like? Often, researchers associate broader impacts with K–12 education, and many great broader impact activities do involve students and teachers, but that is not the only thing that counts for broader impacts. Broader impact activities include but are not limited to citizen science, policy briefs, public talks, science fairs, videos, and more. In fact, the possibilities can be overwhelming without a way to narrow them down.

Many times, this is a good time to reach out to a broader impacts professional on your campus for help. A broader impacts professional is “a specialist in an academic, nonprofit, government, private sector, or community-based organization, who bridges the gap between scientific research and its potential benefits to society” (Iverson et al. 2024). They can often be found in museums, STEM engagement centers, extension offices, and many other places on campus and off.

If you do not have a broader impacts professional on your campus, ARIS has several tools that can help you design your broader impacts, including the BI Wizard (https://aris.marine.rutgers.edu/wizard.php), the BI Plan Checklist (https://aris.marine.rutgers.edu/checklist.php) and the BI Guide Sheet (https://researchinsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/BI-GuidesheetPrintable.pdf). ARIS also has tools to help you evaluate your broader impacts plan (or someone else's, if you are on a review panel) once you are done writing, including the BI Guiding Principles document (https://aris.marine.rutgers.edu/principles.php) and the BI Plan Rubric (https://aris.marine.rutgers.edu/rubric.php).

A good thing to remember about broader impacts is that you do not have to do anything you do not want to do. In fact, usually by the time a researcher has met with a broader impacts professional or used the ARIS tools, they have created broader impact activities that work with their research and their personal interests. Finding this symbiosis can also lead to a researcher developing their impact identity, which “incorporates a scientist's discipline and scholarship; personal preferences, capacities, and skills; institutional context, and the various communities or social settings in which [they] participate” (Risien and Storksdieck 2018).

By starting with the places where you are already engaging (school, nursing home, place of worship, food pantry, etc.) and thinking about activities you enjoy engaging in (social media, sports, volunteering), you can begin to focus on your potential audience, partners and activities. By aligning the contexts in which you find yourself—including personal and professional—you can create broader impact activities that feel less like a burden or add on and more like an extension of the project itself that you look forward to initiating. Risien and Storksdieck (2018) contended that this integration will “result in better outcomes for the scientist and society” because these broader impact activities allow researchers to engage the public “in a way that represents them as a whole person.”

Creating an effective broader impacts plan

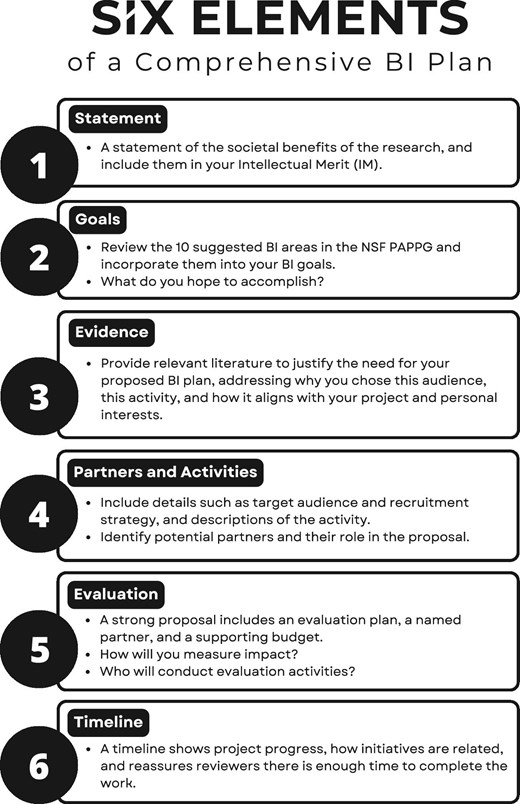

There are as many ways to write a broader impacts plan as there are researchers. What follows is the way that makes the most sense to me and the method we teach in ARIS professional development offerings. See figure 2 for the six elements of a comprehensive broader impacts plan.

The first element is to remember to restate the potential societal benefit of the research itself. This should also be stated in your intellectual merit. This was discussed at length earlier in the article, so I will not discuss it further here.

Second, look back over the 10 suggested broader impacts areas listed in the NSF PAPPG. I like to incorporate them into my broader impacts goals. For instance, if I am creating an afterschool STEM club for middle school students as a broader impact activity, I would write something similar to “The broader impacts of this project will encourage the next generation of scientists and increase science literacy at the middle school level.” This incorporates several of the suggested areas but fits with one activity, and it looks more like an intentional effort rather than a list of goals that you think will result in funding. Review panels pick up quickly on lists of disparate activities that do not match your overall goals for the project. Just as you list goals and activities for the intellectual merit, do the same for your broader impacts. This will be a recurring theme: If you should do it for your intellectual merit, then you should probably do it for your broader impacts as well.

Next, provide relevant literature to demonstrate a need for the broader impacts plan you are proposing. Why this audience? Why this activity? How does this relate to my project and my personal interests? Preliminary data is not necessary in broader impacts plans, but it can be useful to incorporate into your rationale to demonstrate to the reviewers that you have been thoughtful and strategic about the societal outcomes you wish to affect.

Once you have identified your broader impacts goals and thought through your rationale, the next step is to identify potential partners and activities that relate. This is the place in the broader impacts plan where researchers tend to skip on details to save space, and that is a mistake. This is the place to (within reason) share your deepest thoughts: Who is your audience, how will they be recruited, who are your partners, and what is their role? Most broader impacts plans lose momentum here with not enough information. In fact, the NSF instructs proposers that “Sufficient information should be provided to enable the reviewers to evaluate the proposal in accordance with the two merit review criteria” (NSF 2024, emphasis added). Increasingly, reviewers have experience in what it takes to enact broader impact activities and are seeking evidence that you do as well.

Two important things to remember when writing your broader impacts plan is being a good partner and incorporating broader impacts in your budget. Community and campus partners have been burned many times by researchers who come to them at the last minute wanting a major broader impacts program with no budget. Your potential partner deserves respect and is unlikely to come aboard at the last minute without a true relationship. Some partners will not even discuss a grant proposal with someone that is not already partnering with them. Too many times, researchers have asked for something at the last minute and then ghosted the partner—whether the project was funded or not. Unfortunately, this pattern of behavior makes it harder for the next researcher who comes calling. Broader impacts professionals and others on campus spend a lot of time building and repairing relationships with campus and community partners, and they are often unwilling to share those partners with researchers who come calling at the last minute.

NSF budgets can be tight, but it is imperative that you include enough budget to do what you propose for both the intellectual merit and the broader impacts. It can be tempting to cut broader impacts budget to make room for other priorities, just like it is tempting to devote only a small portion of the proposal text to its broader impacts. If the reviewers are left with more questions than answers about your broader impacts plan, that can lead to a poor assessment of the work. If the reviewers do not see appropriate funds devoted to broader impacts and partners, that is a red flag. Many people like to use 10% of the budget as the correct amount to devote to broader impact activities and evaluation, but my answer is you should devote as much budget as you need to fully address your plans. It might be more or less than 10%.

Many times, we confuse activity with impact. Although it is important to document the numbers related to your broader impacts (participants, offerings, etc.), it is also important to think about the long-term impact of your broader impact activities as the fifth element. The extent and cost of your evaluation should be commensurate with your budget and your activities. Large-scale grants may need an external evaluator or team, small-scale grants might use an existing scale or partner with someone on campus. It is important to think about evaluation from the beginning, and, if possible, include your evaluator in your proposal writing. Your broader impact activities should have measurable objectives, and your evaluation partner can help develop them. The NSF states it this way: “Individual projects should include clearly stated goals, specific descriptions of the activities that the PI intends to do, and a plan in place to document the outputs of those activities” (NSF 2024). A strong proposal will include an evaluation plan, a named evaluation partner and a budget that supports evaluation. If you do not know how to find an evaluator, you can visit the American Evaluation Association's website (https://www.eval.org/) and use their “Find an Evaluator” tool. You can also look for evaluation centers on your campus or faculty with evaluation expertise to partner with.

Finally, always include a timeline of activities integrating the intellectual merit and the broader impacts. This visual representation gives the reviewers a view into how the entire project will develop over time and how initiatives are related. This is particularly helpful with complex projects that involve multiple personnel and activities. Without the timeline, the activities can get muddled, and the reviewers sometimes worry that there is not enough time to get everything done. This helps them to understand the project and your vision for accomplishing the work.

As I mentioned earlier, ARIS provides many resources for broader impacts professionals, researchers, and organizations to build their broader impacts capacity. The Program to Enhance Organizational Research Impact Capacity (ORIC) is a community of practice for organizations to “develop in-house expertise necessary to support effective, innovative broader impacts efforts” (ARIS 2025). To date, ORIC has supported 35 organizations, including institutions of higher education and nonprofit research centers, as they built the infrastructure necessary to support researchers in broader impacts. ORIC institutional alumni can even add this to their facilities statement to demonstrate institutional support for broader impacts.

ARIS provides in-person and virtual broader impacts trainings for institutions based on their institutional needs. ARIS also provides professional development support for broader impacts professionals and researchers through an annual broader impacts summit and in-person and virtual offerings on broader impacts across a myriad of topics, including the fundamentals of broader impacts and building your broader impacts identity. The ARIS website (researchinsociety.org) also includes many free resources, including our BI Guide Sheet, the BI Wizard, and video recordings.

Broader impacts are an important part of your NSF proposal, but it is much more. It provides an opportunity for you to connect with the people who benefit from your work and who support it. It is truly where research meets society.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to the ARIS leadership and community for contributing to this work. This material is based on work supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation under Grant No. 2334906, and any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. The author declares that she has no relevant or material financial interests that relate to the research described in this paper.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this research.

Author Biography

Susan D. Renoe ([email protected]) is affiliated with the Department of Strategic Communication at the University of Missouri, in Columbia, Missouri, in the United States.