-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kristin M Winchell, Heroines in HERpetology, BioScience, Volume 74, Issue 7, July 2024, Pages 489–491, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biae013

Close - Share Icon Share

Recently, I was asked who my science heroes are. I had never really considered the question before, and I was somewhat confused that I did not have an answer. Of course, there are many people whose work I admire—but a hero? To me, a hero is someone you identify with and want to emulate; you want to accomplish what they have accomplished, to overcome the same challenges with just as much grit and composure. Nearly all of my mentors, teachers, colleagues, and collaborators have been men. As Umileala Arifin, Itzue Caviedes-Solis, and Sinlan Poo state in their editors’ introduction of Women in Herpetology: “At various points, we each struggled to find role models that looked like us—people who know the unique and yet common challenges we face professionally.” Fortunately, for the next generation of herpetologists, their book gives us 50 new science heroines and a breath of invigorating solidarity.

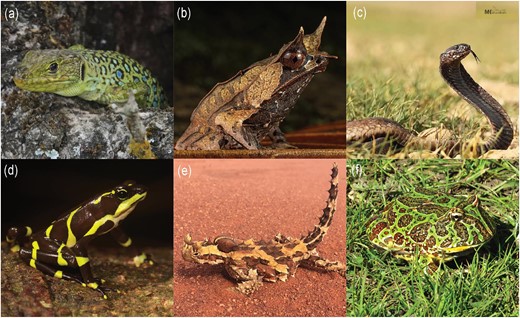

Women in Herpetology is arranged into six sections by geographic regions: Africa, Asia, Oceania, Europe, North and Central America, and South America. Each section offers a tour of the world through the eyes of female herpetologists from different countries. Told in their own words, the unique voices of these women give us a glimpse of their struggles, inspirations, passions, and adventures. Accompanying each story are beautiful illustrations of each scientist with her study organism, commissioned from female artists in each region. At the end of each story is a brief biography of each contributor, including her favorite amphibian or reptile from her country (Figure 1). Sprinkled throughout the text are gems of wisdom and philosophy derived from everyday but life-defining experiences. The stories come from women who loved reptiles, amphibians, and nature from a young age, as well as those who took a less direct path to herpetology by overcoming fears and cultural norms to discover their passion. Regardless of their paths, common themes echoed throughout the stories.

Each contributed story featured the author's favorite reptile or amphibian from their home country. A sampling of a few of these charismatic species: (a) Iberian ocellated lizard (Timon lepidus ssp. Ibericus) from Portugal (CC-BY iNaturalist user desertnaturalist); (b) long-nosed horned frog (Megophrys nasuta) from Singapore (CC-BY iNaturalist user James Jolokia); (c) Egyptian cobra (Naja haje) from Sudan (CC-BY iNaturalist user Mourad Harzallah); (d) limosa harlequin frog (Atelopus limosus) from Panama (CC-BY iNaturalist user Brian Gratwicke); (e) thorny devil (Moloch horridus) from Australia (CC-BY iNaturalist user Nicole Kearney); (f) Bell's horned frog (Ceratophrys ornata) from Argentina (CC-BY iNaturalist user Leonel Roget).

Shared experiences and struggles

As I read through each story, I caught myself smiling at similar experiences I had with so many of the women: catching tadpoles and attempting to keep them alive in a jar to watch them metamorphose as a kid, reminiscing over the thrill of catching my first study organism, and the sense of calm that I felt sitting alone in a forest. It was incredible to see how universal some of these experiences are across the globe. Equally impactful were the experiences I did not share but that so many others in the book did: fear and mistrust of nature, learning and communicating science in a second language, and the legacies of war and societal instability, to name just a few. Of course, there were also experiences that we wish were not shared, like fearing for safety during fieldwork or being discouraged from engaging in specific types of research because of our gender. That women might find each other through these shared experiences offers a sense of solidarity and strength and is one of the greatest gifts this book offers.

Against the odds

In nearly every story, the researchers highlight the people who helped them discover their passion for herpetology. In nearly every story, those people have been men. I found myself struggling to balance my appreciation for the men who believed in these women and supported them with my frustration of a world where so few women exist in these empowering positions. How is it that, in 2023, multiple women can say that they are the first or only female herpetologists in their countries? And why is it so common that a woman often finds herself to be the only female on a field expedition? Many of the stories also highlighted a chance encounter with a foreign scientist as pivotal and essential to shaping their path in science, which made me wonder how many talented young women will never contribute to science because they were not fortunate enough to have this experience. These stories are a wakeup call to researchers to appreciate both the power of small everyday encounters like emails and guest lectures and the responsibility we have to share our knowledge in a way that empowers local researchers to train the next generation of female scientists. Fortunately, several stories also highlight where this has been done effectively, providing hope and guidance for us to do better.

Adventure and inspiration

As every field biologist knows, a large part of why we do what we do is the adventure of it all. Reading through the stories transported me to every corner of the world and left me inspired to go see the incredible landscapes described and the reptiles and amphibians that can only be found there. There are stories of women just starting their careers with a sense of excitement and urgency to learn new things, reminding me of the thrill of starting new projects and beginning my own path in science years ago. There are stories of women who work in conservation and have founded nonprofit organizations, who describe their work with such passion that I felt a deep sense of compassion and stewardship for animals I didn't even know exist. And there are stories of women who have had long and prolific careers full of discoveries, inspiring me to follow in their footsteps. Even the stories of leeches and mosquitos, sleepless nights searching for animals, and exhaustion from working hours on end brought on an urge to get back in the field. I was left with a sense of wonder for how much of the world there is still for me to explore and remembered why I love what I do.

Discovery through diversity

We often hear that diversity is a keystone of discovery, but nowhere have I seen that more beautifully illustrated than in the stories in this text. For example, Sandra Owusu-Gyamfi, from Ghana, wrote about finding the first gravid female of a critically endangered frog: “I joke that females of this species were waiting for someone who shared their gender to find them.” Perhaps there is merit to this joke; the unique experiences we have lead us each to look at the world in slightly different ways. Similarly, the important contributions of diverse experiences in different cultures shines through—in some cases, quite literally. When Anne Deevan-Song, from Singapore, began working in North America in graduate school, she discovered that the method she used back home to find amphibians, shining bright light at night to look for eye shine, was not how her new colleagues searched for them nor how they recommended she locate the rarely encountered eastern spadefoot toad. But when she tried it out, she found that these toads were incredibly abundant and easy to locate, contrary to the published literature and common knowledge at the time. Each of our unique life experiences gives us a perspective that we bring to our science, potentially leading to unexpected and important discoveries.

Solidarity and empowerment

Finally, the stories told in the 322 pages of this book collectively tell a bigger story about solidarity as women in science. As the editors write, “Having broader representation would increase a sense of belonging, a feeling we are not alone, and a confirmation that what we are pursuing is possible.” Echoed throughout the stories is this sentiment, along with calls to action and support. The editors take the call for solidarity one step further by donating profits from the book sales to create scholarships for women to attend herpetological conferences.

In summary, Women in Herpetology is far more than simply a collection of 50 stories from around the world. The compilation is simultaneously a tribute to women in science, a strong voice of solidarity for those struggling to make their mark in this field, an inspiration to girls and women everywhere, an exploration of various paths and careers in science, a celebration of diversity and biodiversity, and a tour of the world and all of its wonders. I will be gifting this book to every female herpetologist that comes through my lab, so that they can see themselves in the struggles and successes of the women who have come before them. I hope that this is just the first of these books, because these stories capture only a fraction of the diversity in only a quarter of countries around the world; there are so many more stories that can inspire and embolden the next generation of women herpetologists just waiting to be told.

Author Biography

Kristin Winchell is affiliated with the Biology Department at New York University, in New York, New York, in the United States.