-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Pawel Michalak, Echo of extinction: The Ivory-billed Woodpecker's tragic legacy and its impact on scientific integrity, BioScience, Volume 74, Issue 11, November 2024, Pages 740–746, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biae072

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Among the current surge in extinction rates, exceeding between 100 and 1000 times the prehuman background rate, a multitude of species quietly fade away, largely escaping the notice of our collective awareness. The extinction of only a select few species has the power to captivate public attention, stir emotions, and ignite debates comparable to the case of the ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis). Reports purporting a rediscovery of this long-extinct species periodically surface and find their way into peer-reviewed journals, attracting worldwide attention from the public media. This phenomenon persists despite a glaring lack of evidence supporting such an exceptional claim, in disconnect with principles of population biology or even common sense, thereby risking erosion of public trust in the foundations of nature conservancy and the integrity of scientific methodologies in general. The tragic fate of this iconic species therefore holds significance beyond ecology, providing deep insights into extinction and conservation while highlighting the need for refinement of scientific rigor and standards of evidence in the peer review process and beyond.

Once widespread throughout the southeastern United States and separately in Cuba, the charismatic ivory-billed woodpecker went extinct primarily due to the logging of bottomland hardwood forests, its main habitat, and the ruthless actions of collectors in the early twentieth century. The last universally accepted sighting of an ivory-billed woodpecker in the United States took place in Louisiana by Audubon Society artist Don Eckelberry, who followed presumably the last individual, documenting it with sketches for 2 weeks in April 1944 (figure 1). The last breeding pairs at the same site, the Singer Tract, had been successfully photographed and filmed years earlier (figure 2), after overcoming the challenge of transporting the then-heavy cameras and films with horse-drawn carts (Allen and Kellogg 1937). Anecdotal reports of ivory-billed woodpeckers continued after 1944, but none have been substantiated with compelling evidence, despite extensive campaigns, heightened public awareness, and systematic search efforts involving the US government, numerous academic institutions, modern surveillance methods, and mobilizing masses of naturalists and birdwatching enthusiasts. More than US$20.3 million in the federal and state government funding was spent on the extinct bird between 2005 and 2013, in addition to private efforts (Troy and Jones 2023). The combined search effort from 2004 to 2021 alone in Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, and Illinois has been estimated at almost 580,000 hours (Troy and Jones 2023). This figure does not account for searches without reported estimates of effort, multiple surveys not specifically targeting the ivory-billed woodpecker, or any other popular wildlife-oriented activities.

Don Eckelberry's painting of the last known ivory-billed woodpecker. Image: Don Eckelberry, WGCU.org.

Ivory-billed woodpecker pair photographed by a Cornell University team in Louisiana 1935 (Allen and Kellogg 1937). Image: Wikipedia.

Out of the 10,749 extant avian species to date, a mere 124 (1.2%) lack any modern documentation with publicly available photos, audios, or videos taken live in the field (Berryman and Rutt 2013). These species, such as Itombwe owl (Tyto prigoginei) or saffron-breasted redstart (Myioborus cardonai), are the most poorly known birds on Earth, typically as a result of their secretive, often nocturnal, lifestyles and endemism limited to remote, extremely inaccessible places in politically volatile countries, such as table-top mountains in Venezuela. The assertion that the ivory-billed woodpecker has managed to survive, breed, and at the same time evade photographic and video documentation in the United States, a country currently with 45.1 million birdwatchers—an impressive 20% of the population, most of them with digital cameras, who collectively devote millions of days to birdwatching each year (USFWS 2016)—is an exceptional claim. The additional fact that the ivory-billed woodpecker's habitat has been mostly obliterated, with its current few remnants heavily harvested, transformed, and degraded, makes the proposition even less rational.

The ivory-billed woodpecker itself, a large and noisy bird that could scarcely have a single meal without being heard from a distance and whose last known individual stayed close enough to an artist to get depicted in watercolor painting, presents an ironic contrast to the notion of an elusive species. It was the largest of the woodpecker species north of Mexico and the third largest in the world, excavating nest cavities exceeding even those by the similar-sized pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) and leaving behind distinct feeding marks on trees with stripped bark (Tanner 1942) comparable to those made by black bears (Ursus americanus). It often reused its conspicuous feeding and roost sites (Tanner 1942).

The supposition that ivory-billed woodpeckers could stay put for generations in a secluded forest somewhere in Arkansas, Florida, or Louisiana also contradicts our understanding of the species’ biology and avian behavior in general. Unlike the pileated woodpecker, which tends to be territorial all year-round (Bull and Holthausen 1993), the ivory-billed woodpecker was described as being semiterritorial and nomadic, traveling large distances to search for areas with large amounts of dead wood (Tanner 1942). Even the rare, endangered, and highly sedentary red-cockaded woodpecker (Dryobates borealis), which is narrowly adapted to pine savannas dominated by longleaf pines (Pinus palustris) in the southeastern United States, is capable of long-distance dispersal (Walters et al. 1988, Ferral et al. 1997) and can be seen outside its typical habitat. The remaining breeding sites of the relatively small species (nearly one-third the body length of the ivory-billed woodpecker) are situated roughly within the historical distribution of the ivory-billed woodpecker, and yet have been successfully tracked down and monitored for decades. Their nest cavities are known, most individuals have been banded, and some have been equipped with tracking transmitters.

However, sensational claims of ivory-billed woodpecker sightings occasionally emerge and make their way into peer-reviewed journals (Collins 2011, 2017a, 2017b, Fitzpatrick et al. 2005, Hill et al. 2006, 2018, 2019, Latta et al. 2023). The most notable among these was the 2005 publication in Science (Fitzpatrick et al. 2005), which garnered widespread global attention through extensive coverage in mass media. The latest instance came from a 2023 report in Ecology and Evolution (Latta et al. 2023). The reports entailed extensive search and monitoring endeavors in the field. For example, a 145 square kilometer (km2) area in Arkansas was systematically searched by at least 30 observers who dedicated a collective total of 4750 party hours within a year to scour the area for birds, signs of their foraging activities, and roost or nest cavities (Fitzpatrick et al. 2005). An additional 2693 hours of recordings from audio surveillance were collected. Another report (Latta et al. 2023) resulted from a decade-long effort to survey a 90 km2 area in Louisiana. In addition to direct search by observers, the latter involved automatic monitoring with acoustic recorders, trail cameras, and drone video surveillance (Latta et al. 2023). It amassed an estimated 70,000 hours of audio, 472,550 camera hours, and 1089 hours of video data.

In stark disproportion to these extensive efforts, the reported encounters with purported ivory-billed woodpeckers have been scarce and brief, sharing a number of striking characteristics.

They are reported not by random, casual observers but typically by select enthusiasts deeply committed and emotionally attached to the idea of the ivory-billed woodpecker's survival against all odds. These individuals have often dedicated years to the hopeful pursuit of clues supporting the species' continuing existence. Therefore, as one of the former searchers admitted in hindsight, “many searchers may have been subconsciously biased and, as a result, not sufficiently cautious in their identifications under field conditions” (Sykes 2016).

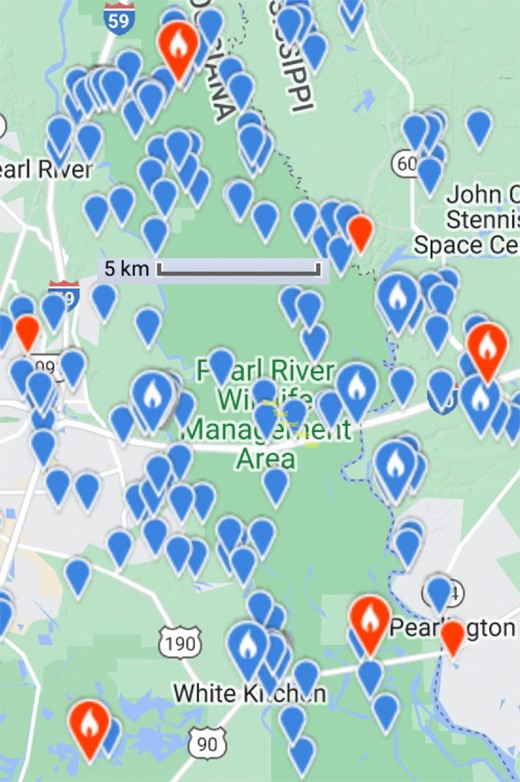

The purported sightings invariably occur in flooded southern swamp forests deemed by the dedicated enthusiasts as the ideal habitat for the species and less often, if at all, frequented by other observers (Hill 2007, Collins 2019). The vastness and inaccessibility in the descriptions tend to be exaggerated: “Alligators, wild boars, and venomous snakes are abundant, and there is a danger of heat stroke during the summer and hypothermia during the winter” (Collins 2019), being a description of an area of less than 100 km2, a mere 40 kilometers (km) away from New Orleans, the most populous city in Louisiana. The LSU Museum of Natural Science in Baton Rouge, historically one of the most vibrant ornithological centers in the Unites States, is about 145 km away. An area of 100 km2 would by no means be vast enough even for a single ivory-billed woodpecker, let alone a breeding population, to hide in for long. Meanwhile, there are abundant eBird reports of other bird species from the same area (Pearl River swamp), with the widest gap between adjacent observations of pileated woodpeckers, as an example, being less than 5 km (figure 3).

Distribution of 342 eBird reports (years 1978–2024) of pileated woodpeckers from the Pearl River area in Louisiana. Image: Courtesy of Macaulay Library, eBird.

The sightings are typically no more than fleeting glimpses, described as stealthy flyovers of a quickly disappearing bird (Fitzpatrick et al. 2005, Hill et al. 2006, Collins 2019), reported by individual observers rather than corroborated by groups of people. The reported behavior lacks any complexity; birds vocalizing, foraging, preening, or interacting with each other have not been seen. The few instances of perching birds recorded by surveillance cameras occurred in foggy conditions (Latta et al. 2023), making it impossible to rule out the similar pileated woodpecker. The putative ivory-billed woodpeckers fail to reappear in front of the surveillance cameras every time the weather and lighting conditions are more favorable. In addition, no nests, fledglings, or roost sites associated with the ivory-billed woodpecker have been identified since 1939 (Tanner 1942).

No compelling visual evidence is provided. One would reasonably anticipate that modern photographs and videos accompanying the proof of persistence surpass those taken about 90 years ago at Sanger Tract in terms of quality (figure 2). After all, extremely rare birds, including migrants and vagrants straying from their typical areas of distribution, as well as truly secretive breeding rarities and their nests in challenging environments, are being photographed with remarkable precision on a daily basis worldwide.

However, pixels representing the objects claimed to be rediscovered ivory-billed woodpeckers constitute only marginal fractions of the presented images, with the objects typically photographed in poor light conditions and appearing too blurry or distant for identification. The image quality consistently falls short of being sufficient to eliminate the pileated woodpecker or, in specific instances, less similar birds, such as the red-headed woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus) or even the wood duck (Aix sponsa). Laymen are often unable to locate a bird or distinguish it from inanimate objects in these images. Hypothetically, if such images were submitted to bird rarities committees as evidence for the vagrancy of a black woodpecker (Dryocopus martius), a Eurasian species, from Europe to North America or a pileated woodpecker the other way around, the committees’ experts would refuse reviewing them because of the poor quality of the photos and the lack of self-skepticism from their authors.

The latter, themselves, make insufficient effort to rule out either photographic anomalies, such as reflections, heat distortion, dust, insects, and editing alterations, or biological variations in common species, including less typical postures or color aberrations, such as leucism. Additional clues suggesting the more common species tend to be ignored. For example, figures 4–6 from Latta and colleagues (2023) highlighted the putative white saddle indicative of the ivory-billed woodpecker. However, the authors seem to have overlooked the fact that the extremely poor-quality video footage (their appendix 3) from which the photos were extracted demonstrates that the saddle effect decreases and effectively disappears with the bird's movements, suggesting a common pileated woodpecker with incidental light reflection on its back.

Sound recording of ivory-billed woodpecker in the Singer Tract, Louisiana, April 1935. Photograph: James T. Tanner, then a Cornell University graduate student, printed courtesy of Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge, US Fish and Wildlife Service (Mss. 4171), Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Libraries, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in the United States.

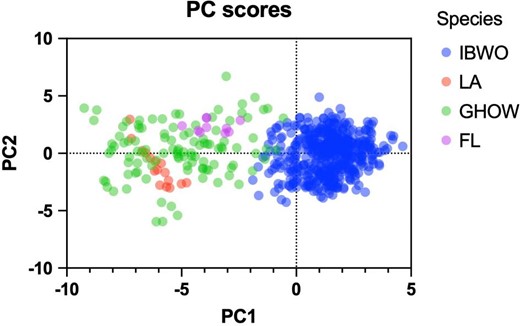

Principal component analysis of 22 harmonic parameters derived from call sonograms of ivory-billed woodpeckers (IBWO, Macaulay Library ML6784), Florida 2006 recordings (FL, Hill et al. 2006), Louisiana 2017 recordings (LA, Latta et al. 2023), and great horned owls (GHOW, Macaulay Library), showing that the Florida and Louisiana recordings calls tightly group with great horned owl calls. Principal components (PC) 1 and 2 account for 40.8% and 15.9% of variance, respectively. Linear discriminant analysis corroborates the result and provides estimates that the Florida and Louisiana recordings classify as great horned owls with posterior probability equal to .78 and 1, respectively.

Leucistic pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) male photographed in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, on 14 January 2016. Photograph: Gerard Beyersbergen.

They also attempted to measure the wingspan of a putative ivory-billed woodpecker from drone footage (Latta et al.’s 2023 appendix 8), but their own estimate (74.7 cm ± 7.9 cm) falls within the typical range for a pileated woodpecker (Bull and Jackson 1995, Koenig 1996). Another poor drone video (Latta et al.’s 2023 appendix 9), purportedly demonstrating a direct comparison between an ivory-billed woodpecker and a red-headed woodpecker, depicts two extremely distant and blurry woodpeckers appearing to be approximately the same size (although the former should be at least twice as large as the latter). Images presented as proof of the existence of the ivory-billed woodpecker in eastern Arkansas (the so-called Luneau video; Fitzpatrick et al. 2005) have been debunked by others (Jackson 2006, Sibley et al. 2006, Collinson 2007).

No convincing audio evidence is provided. The occasionally heard and recorded calls and nonvocal sounds (drumming) are never visually connected to their source, which is inconsistent with historical accounts of how this species was typically detected. The primary call of the ivory-billed woodpecker was a distinctive kent sound, characterized by a nasal yank often repeated in a series. A historical recording of this call dates back to 1935 and remains well documented (figure 4). Despite routine use of this recording as playback by the searchers in the field, no response has ever been obtained. Other species, including gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis), red-breasted nuthatches (Sitta canadensis), white-breasted nuthatches (Sitta carolinensis), and blue jays (Cyanocitta cristata), are known to produce sounds similar to the ivory-billed woodpecker's kent calls (Tanner 1942, Jackson 2002). Blue jays, notorious of their vocal mimicry (Ramsey 1972), likely imitate the kent call heard from the playbacks (Fitzpatrick et al. 2005, Jackson 2006). Sonograms of calls published as those of rediscovered ivory-billed woodpeckers (Hill et al. 2006, Latta et al. 2023) significantly differ from those based on the authentic 1935 recording (see the supplemental material). Using principal component analysis and linear discriminant analysis of harmonic parameters derived from the sonograms, I demonstrate that the kent-like sounds closely match the squawk calls of great horned owls (Bubo virginianus) or imitations thereof by blue jays rather than ivory-billed woodpecker calls (figure 5 and the supplemental material). The squawk of the great horned owl, typically associated with agitated females (Kinstler 2009), is a rare and seldom-heard call, especially during the daytime, making it generally unfamiliar to most listeners.

In addition to kent-like calls, contemporary ivory-billed woodpecker enthusiasts are actively engaged in the field detection of the nonvocal double-rap sounds attributed to the species, akin to those made by other Campephilus woodpeckers such as the pale-billed woodpecker (Campephilus guatemalensis). However, uncertainties surround the double-knock sounds, starting with their actual frequency and significance for the species. Despite independent descriptions of ivory-billed woodpeckers’ drumming and tapping sounds (Thompson 1889, Bendire 1895, Lowery 1955), only one account (Tanner 1942) mentions the double knock. The historical audio recordings from 1935 capture occasional tapping sounds, but none of them feature double knocks. Consequently, there are no confirmed recordings of ivory-billed woodpecker double-knock sounds for comparative analysis. On the other hand, double-knock sounds by other species, such as the pileated woodpecker and the red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus), are not uncommon (for examples, see the supplemental material), therefore their presence in the extensive audio recordings amassed during search efforts should be all but surprising. Double raps presented as acoustic evidence for ivory-billed woodpecker's presence are also very similar to those produced by wing collisions of flying ducks (Jones et al. 2007). However, these recordings tend to be uncritically presented as sounds made by ivory-billed woodpeckers (Hill et al. 2006) and even cross-referenced for comparison in a circular reasoning manner. For example, Latta and colleagues (2023 and figure 3 therein) compared their recording of a double knock with those reported by Hill and colleagues (2006), asserting that the interknock interval of 61 milliseconds (ms) falls within the anticipated 60–120 ms range. This comparison, however, lacks a reference to a recognized ivory-billed woodpecker sound, whereas the remeasured interpulse interval turns out to be closer to 55 ms than the claimed value and range, being more consistent with a mechanical or environmental noise than a woodpecker knocking on a tree (see the supplemental material).

These encounters lack support from any other physical evidence; no ivory-billed woodpecker carcasses, feathers, eggshells, or feces that could enable DNA forensics have ever been found. A feather found in central Florida in 1968 and identified as the innermost secondary of an ivory-billed woodpecker has not been tested for DNA. Its origin has raised suspicion of a hoax, because an ivory-billed woodpecker specimen of 1929 from the collection at the nearby Florida Museum of Natural History lacks its innermost secondary feather (Sykes 2016).

The sightings and sound detections dry up soon after the reports are published, despite intensified efforts and public interest (Sibley 2007). The 2004 report from eastern Arkansas (Fitzpatrick et al. 2005), in particular, electrified millions of birdwatching enthusiasts worldwide and sparked a frenzy of woodpecker tourism, with 40 charter flights from England alone (Crocker 2009).

Carl Sagan's (1996) famous phrase “the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence” encapsulates the challenge of definitively proving a species extinct. Consequently, demonstrating beyond all doubt that a species is extinct is essentially impossible, because there is always some possibility, however slim, that the searches have been inadequate and that the species persists against all odds (Elphick et al. 2010). Therefore, any assessment of extinction is inherently a probabilistic statement (McInerny et al. 2006). On average, however, only about 4 years pass between a species’ last confirmed sighting and its estimated extinction date, with the 95% confidence intervals around extinction dates extended 9–26 years for avian species (Elphick et al. 2010). Statistical modeling methods specifically applied to infer the extinction time demonstrate that the ivory-billed woodpecker is extinct regardless of the method used, the underlying assumptions, or the treatment of the data (Gotelli et al. 2012, Solow et al. 2012, Solow and Beet 2014, Kodikara et al. 2020). For example, a Bayesian hierarchical approach produces a median extinction year at 1940 with a 95% upper bound in 1945, and the posterior probability that extinction occurred during the period being equal to 1 (Kodikara et al. 2020). To argue for the species’s survival to the present day, the ivory-billed woodpecker's population in 1929–1932 would have needed to exceed 50,000 (Gotelli et al. 2012). Such a population figure contradicts the historical evidence, considering the species’ rapid decline after 1894, with the last museum specimen collected in 1932 (Jackson 2004).

The continued existence of the ivory-billed woodpecker would also necessitate a recently thriving breeding population, cumulatively numbering in the hundreds of individuals. Under such a scenario, the species would not even be classified as the rarest breeding bird in Louisiana, Arkansas, or other states, a status further contrasted by even more infrequent nonbreeding migrants and vagrants in these areas. This contrast highlights the anomaly of the ivory-billed woodpecker's allegedly undetected survival amid intensive wildlife monitoring. This assertion becomes even more doubtful when juxtaposed with the well-documented sightings of exceptionally rare melanistic, albinistic, and leucistic pileated woodpeckers (Short 1965, Snyder et al. 2009, Sykes 2016). These unique variants have been consistently observed, photographed, and filmed, in spite of their extreme rarity in the population, the generational irregularity in the occurrence of the underlying genetic mutations, and their potentially decreased fitness. Of particular interest are the aberrant pileated woodpeckers that exhibit extensive white wing patches, including secondaries—features that resemble the ivory-billed woodpecker’s (figure 6; Snyder et al. 2009). This contrast underscores the improbability of the ivory-billed woodpecker's unnoticed persistence given the attention and documentation afforded to truly rare avian species, aberrant variants among common species, or interspecies hybrids, some of which may have occurred only once (McCarthy 2006).

Another Carl Sagan's principle, stating that “exceptional claims require exceptional evidence,” is deeply embedded in the scientific method, peer review, and has become a cornerstone for critical thinking, rational thought, and truth-seeking discourse (Marc 2012). However, this fundamental rule somehow appears to be overlooked by authors, reviewers, journal editors, and public media when it comes to the alleged persistence of the ivory-billed woodpecker. The blame cannot rest on the enthusiasts who are deeply engaged in pursuing their passion, investing time and often personal resources in the search for the ivory-billed woodpecker. The primary controversy in this case extends beyond familiar issues, such as bird misidentification, expert bias, occasional unacknowledged errors, or media sensationalism, because these are neither novel nor unexpected phenomena. Rather, the crux of the controversy lies in the failure of peer-reviewed journals to uphold the scientific tenets of skepticism, reproducibility, and reliance on verifiable evidence, which are essential for maintaining the integrity of scientific inquiry and public trust.

The evidence presented to support the existence of an ivory-billed woodpecker demands a significantly higher level of scrutiny than would be needed to confirm an extant species. This requirement aligns with common sense, logical intuition, and scientific practice, including the application of basic Bayesian inference (Lopez Puga et al. 2015). Given the current level of misinformation and confusion surrounding the species, reports claiming the presence of ivory-billed woodpeckers should not be published in peer-reviewed journals unless there is independent verification of the bird's existence and unless the evidence presented unequivocally rules out any possibilities of misidentification or a hoax. This stringent criterion, already a standard enforced by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS 2021) and eBird, the citizen-based bird observation network affiliated with Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society (Sullivan et al. 2009), ought to be similarly embraced by scientific journals. Concerningly, there have been accounts of a bias within certain journals against those who question the so-called evidence that has been published and rationally advocate for the official declaration of the species’ extinction (Troy and Jones 2023).

The poignant saga of the ivory-billed woodpecker serves as a stark reminder of the fragility of our natural world and the intricacies involved in scientific integrity and nature conservation efforts. As we continue to grapple with the realities of species extinction and the loss of biodiversity, the case underscores the necessity of adhering to rigorous scientific standards and methodologies, particularly when dealing with claims of extraordinary nature. It highlights the importance of skepticism and reproducibility in scientific pursuits, as well as the dissemination of knowledge, especially in an era where misinformation can proliferate all too easily.

Acknowledgments

I thank the Macaulay Library at the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology for sharing their sound recordings and LSU Special Collections for their permission to use their photos.

Author Biography

Pawel Michalak ([email protected]) is affiliated with the Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, in Monroe, Louisiana, in the United States, as well as with the Institute of Evolution at the University of Haifa, in Haifa, Israel.