-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

T. S. Shah, J. Z. Liu, J. A. B. Floyd, J. A. Morris, N. Wirth, J. C. Barrett, C. A. Anderson, optiCall: a robust genotype-calling algorithm for rare, low-frequency and common variants, Bioinformatics, Volume 28, Issue 12, June 2012, Pages 1598–1603, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts180

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Motivation: Existing microarray genotype-calling algorithms adopt either SNP-by-SNP (SNP-wise) or sample-by-sample (sample-wise) approaches to calling. We have developed a novel genotype-calling algorithm for the Illumina platform, optiCall, that uses both SNP-wise and sample-wise calling to more accurately ascertain genotypes at rare, low-frequency and common variants.

Results: Using data from 4537 individuals from the 1958 British Birth Cohort genotyped on the Immunochip, we estimate the proportion of SNPs lost to downstream analysis due to false quality control failures, and rare variants misclassified as monomorphic, is only 1.38% with optiCall, in comparison to 3.87, 7.85 and 4.09% for Illuminus, GenoSNP and GenCall, respectively. We show that optiCall accurately captures rare variants and can correctly account for SNPs where probe intensity clouds are shifted from their expected positions.

Availability and implementation: optiCall is implemented in C++ for use on UNIX operating systems and is available for download at http://www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/software/opticall/.

Contact: [email protected]

1 INTRODUCTION

Burgeoning whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing projects are likely to require large-scale microarray-based follow-up studies. Already, custom arrays, such as Metabochip and Immunochip, utilize SNPs identified through population-based sequencing efforts such as 1000 genomes to better survey loci known to underpin variation across related phenotypes (Trynka et al., 2011). Typically, the allelic probes on these custom arrays have undergone less stringent quality control (QC) compared to those that make it onto mass-produced GWAS arrays. This drop in probe quality, in addition to a greater focus on low-frequency and rare variants (those with minor allele frequencies 0.5–5% and <0.5%, respectively; The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, 2010) presents many problems for existing genotype-calling algorithms.

Genotype-calling algorithms use normalized measures of DNA binding to allele specific probes to ascertain the genotype of an individual at a given SNP. As an example, a wild-type homozygous genotype at a particular SNP would have a high intensity value for the wild-type allelic probe, and little or no intensity for the alternative allelic probe. A heterozygous sample would have intermediate intensities for both probes. Existing callers vary in both the statistical models they apply, and how they utilize the intensity data across individuals and SNPs.

Illumina's proprietary genotype-calling software, GenCall, uses a custom clustering algorithm that encompasses several biological heuristics to determine genotypes from intensity clouds obtained by gathering all individuals at a single SNP. If less than three well-defined genotype clusters are observed, GenCall uses a neural network model to estimate the location and shape of the undefined clusters. GenCall is designed to work on Illumina arrays and, being based on a pretrained neural network, its performance on a new dataset is dependent on how close the new data matches the data used to train the network.

Another commonly used genotype-calling algorithm, Illuminus (Teo et al., 2007), also designed for Illumina arrays, again clusters intensity data across samples on a per SNP basis, using an unsupervised clustering method based on a mixture model of Student's t-distributions. This unsupervised approach removes the need for a called training set. However, low-frequency SNPs and/or small sample sizes can result in poorly defined clusters and inaccurate genotype calls due to the small number of rare allele observations. Giannoulatou et al. (2008) discovered within-sample intensity data also tended to cluster into three distinct genotype groups. On the basis of this observation, they created GenoSNP, a within-sample genotype-calling algorithm. Clustering within sample can be advantageous for rare variants and small sample sizes, as three well-defined clusters are always observed. A drawback of the approach is that intensity variation between SNPs is not accounted for, resulting in inaccurate genotype calls for SNPs where intensity clusters are shifted from their expected positions.

We have developed optiCall, a novel genotype-calling algorithm that uses both within and across sample intensity data to accurately ascertain genotypes from across the minor allele frequency spectrum. In the following sections, we describe optiCall and compare its output to that from existing algorithms using 4537 samples from the 1958 British Birth Cohort (Power and Elliott, 2006) genotyped on the Immunochip, an Illumina iSelect HD custom array (Cortes and Brown, 2011).

2 METHODS

2.1 Data

Illumina uses a six degree of freedom affine transformation to normalize data for channel-dependent background and global intensity differences. The data input to the algorithm have a normalized intensity point x=(x(1),x(2)) for each sample and SNP on the array, indicating the binding strength of the sample's DNA to the probes for each of the two alleles being interrogated at the SNP.

2.2 Creating the within and across sample prior

The model is fitted to the data by inferring values for the πi, μi, Σi to maximize the likelihood of the data by an expectation maximization (EM) procedure (Dempster et al., 1977). The parameters μi, Σi are fixed for the unknown class [by default (0,0) and 100×I2, where I2 is the 2 × 2 identity matrix] so that the probability density is even over parameter space, and outliers are assigned unknown. The vi for all classes are also fixed at 1.

When performing inference, initial values for the μi, Σi of the genotype classes are obtained from a run of the k means ++ clustering algorithm for k equal to three (Arthur and Vassilvitskii, 2007), and all the πi are each set to 0.25. Using the EM algorithm, the initial parameter values are altered so that they maximize the log-likelihood of the data. The unknown class is treated like the genotype classes during inference, except for its mean and covariance parameters remaining fixed. The EM algorithm obtains a (possibly local) maximum for the log-likelihood by alternating between an expectation (E) step, and a maximization (M) step. For the E-step, the expected value of the log likelihood is calculated, with respect to the latent variable given the current values of the parameters. Next the M-step finds the parameters to maximize this expected log-likelihood, the parameter values are updated, and the algorithm moves to the next iteration of EM steps.

The across sample and SNP clustering happens only once, and the resulting mixture model provides prior information in subsequent per SNP, across sample, clustering steps.

2.3 Genotype calls across samples with prior information across SNPs

and

and  are the mean and SD of the intensity data of the current SNP, μhet is the optimal μi of the heterozygous class from (2.2),

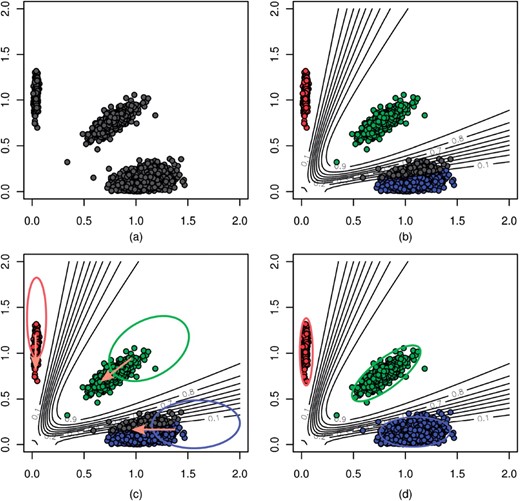

are the mean and SD of the intensity data of the current SNP, μhet is the optimal μi of the heterozygous class from (2.2),  is the SD of the random subset S from (2.2), and bracketed subscripts show the allele (1 or 2) over which the mean or SD is calculated, for points (x(1),x(2)). The modification to the EM procedure occurs at the E-step when calculating the expected value of zij. If the maximum genotype posterior probability for an intensity point p(gj=i|xj) is above 0.9, according to the model inferred in (2.2), the expected value for zij is calculated using these genotype posteriors, instead of the values of πi in the current clustering. This way, points with highly confident genotype posteriors by the model in (2.2), but possibly forming a sparse cluster, can still guide the current clustering (Fig. 1b). The EM algorithm runs for 15 iterations but stops early if genotype calls are unchanged for more than three consecutive iterations.

is the SD of the random subset S from (2.2), and bracketed subscripts show the allele (1 or 2) over which the mean or SD is calculated, for points (x(1),x(2)). The modification to the EM procedure occurs at the E-step when calculating the expected value of zij. If the maximum genotype posterior probability for an intensity point p(gj=i|xj) is above 0.9, according to the model inferred in (2.2), the expected value for zij is calculated using these genotype posteriors, instead of the values of πi in the current clustering. This way, points with highly confident genotype posteriors by the model in (2.2), but possibly forming a sparse cluster, can still guide the current clustering (Fig. 1b). The EM algorithm runs for 15 iterations but stops early if genotype calls are unchanged for more than three consecutive iterations.

Calling a SNP with optiCall. In (a) intensity data is taken from all samples at the SNP. Then, using a data-derived (within and across sample) prior, and adjusting class membership probabilities based on the prior in an EM procedure (b and c), a mixture model of Student's t-distributions is fitted to the data (d)

2.4 Measuring clustering quality and reclassifying poorly clustered SNPs

is the mean of the yj over the second axis, and k is a shift parameter for the location of the heterozygous class, that takes one of three values, 0.45, 0.5 or 0.55, resulting in three sets of initial values dependent on the value of k. For each set of starting values, the EM algorithm is run until genotype calls are concordant for two consecutive iterations, and the optimal parameters are chosen to be the final values with the highest likelihood.

is the mean of the yj over the second axis, and k is a shift parameter for the location of the heterozygous class, that takes one of three values, 0.45, 0.5 or 0.55, resulting in three sets of initial values dependent on the value of k. For each set of starting values, the EM algorithm is run until genotype calls are concordant for two consecutive iterations, and the optimal parameters are chosen to be the final values with the highest likelihood.Genotype calls are made using genotype posterior probabilities [using the πi inferred from this step unlike (2.3)] with a 0.7 call threshold. By default, SNPs that fail the HWE test subsequent to this step have all genotypes called unknown.

In our experiments, we have found the occurrence of the rescue step, and the subsequent chances of a successful rescue, to vary with the quality of the dataset. On a number of Immunochip datasets, rescue steps tended to occur on between 3 and 10% of SNPs, with 30–50% being successful.

3 RESULTS

To test the performance of optiCall, and compare it to existing algorithms, we used data from 4537 individuals from the 1958 British Birth Cohort who were genotyped using the Immunochip, an Illumina iSelect HD custom array designed for deep replication of autoimmune disease genome-wide association study results and fine-mapping within 184 known autoimmune disease loci (Trynka et al., 2011). Genotypes were called at 192 402 SNPs using optiCall, GenCall, Illuminus and GenoSNP. Default parameters were used when running each of the algorithms.

The genotype data from each algorithm underwent a simple QC protocol to reflect a typical association study. SNPs failed QC if they had a call rate <98% or HWE P<10−5. Table 1 shows the QC results for each caller across the dataset.

Summary statistics of calling and QC results on 192 402 Immunochip autosomal SNPs

| Caller . | Mean call rate (%) . | Number with call rate <98% . | Number with HWE P<10−5 . | Number of QC fails . | Number of unique QC passes . | Number of unique QC fails . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illuminus | 99.44 | 6311 | 8096 | 10 263 | 2305 | 2852 |

| GenoSNP | 97.63 | 19 432 | 15 239 | 22 572 | 310 | 8505 |

| GenCall | 96.01 | 13 861 | 9413 | 15 665 | 156 | 1454 |

| optiCall | 97.06 | 7440 | 7210 | 10 006 | 796 | 168 |

| Caller . | Mean call rate (%) . | Number with call rate <98% . | Number with HWE P<10−5 . | Number of QC fails . | Number of unique QC passes . | Number of unique QC fails . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illuminus | 99.44 | 6311 | 8096 | 10 263 | 2305 | 2852 |

| GenoSNP | 97.63 | 19 432 | 15 239 | 22 572 | 310 | 8505 |

| GenCall | 96.01 | 13 861 | 9413 | 15 665 | 156 | 1454 |

| optiCall | 97.06 | 7440 | 7210 | 10 006 | 796 | 168 |

Call rate is defined as the proportion of genotype calls for a SNP assigned a genotype other than unknown. The QC threshold is set at a call rate of <98% or <10−5 HWE P-value. A unique QC pass/fail is a SNP that passed/failed QC uniquely to the given caller.

Summary statistics of calling and QC results on 192 402 Immunochip autosomal SNPs

| Caller . | Mean call rate (%) . | Number with call rate <98% . | Number with HWE P<10−5 . | Number of QC fails . | Number of unique QC passes . | Number of unique QC fails . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illuminus | 99.44 | 6311 | 8096 | 10 263 | 2305 | 2852 |

| GenoSNP | 97.63 | 19 432 | 15 239 | 22 572 | 310 | 8505 |

| GenCall | 96.01 | 13 861 | 9413 | 15 665 | 156 | 1454 |

| optiCall | 97.06 | 7440 | 7210 | 10 006 | 796 | 168 |

| Caller . | Mean call rate (%) . | Number with call rate <98% . | Number with HWE P<10−5 . | Number of QC fails . | Number of unique QC passes . | Number of unique QC fails . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illuminus | 99.44 | 6311 | 8096 | 10 263 | 2305 | 2852 |

| GenoSNP | 97.63 | 19 432 | 15 239 | 22 572 | 310 | 8505 |

| GenCall | 96.01 | 13 861 | 9413 | 15 665 | 156 | 1454 |

| optiCall | 97.06 | 7440 | 7210 | 10 006 | 796 | 168 |

Call rate is defined as the proportion of genotype calls for a SNP assigned a genotype other than unknown. The QC threshold is set at a call rate of <98% or <10−5 HWE P-value. A unique QC pass/fail is a SNP that passed/failed QC uniquely to the given caller.

Calls from Illuminus and GenoSNP produce the most discordant results at QC (with 5157 and 8815 unique QC passes and fails, respectively) whereas GenCall and optiCall appear to have more overlapping QC outcomes with other callers.

3.1 SNPs passing/failing QC

In an association study, if many SNPs fail QC because of poor genotype calling, potential casual variants may be missed. However, too many calls incorrectly passing QC would result in increased false-positive associations, and more overheads in subsequent follow-up and replication.

To assess clustering quality and accuracy, 600 unique QC pass SNPs and 600 unique QC fail SNPs were selected at random and manually called using a modified version of Evoker (Morris et al., 2010). All manual calling was carried out blind to genotype calls from any of the algorithms. The 1200 SNPs were split into four subsets, each manually called by a different person. Any SNPs deemed difficult to call were blind re-called by all four human callers, and the consensus genotypes were taken forward. Manually called genotypes were then compared to those from each of the genotype-calling algorithms, classifying SNPs passing QC for both the algorithm and manual call set as true-pass (TP) SNPs, and SNPs failing QC in the manual calls but passing QC for the given algorithm as false-pass (FP) calls. Similarly, SNPs failing QC for both the manual calls and the algorithm were classified as true-fail (TF) SNPs, while false-fail (FF) SNPs fail QC for the given algorithm only. Sensitivity and specificity were then calculated for each of the algorithms (Table 2).

| Caller . | TP . | FP . | TF . | False-fail . | Sensitivity/specificity . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illuminus | 574 | 260 | 134 | 232 | 0.71/0.34 |

| GenoSNP | 196 | 13 | 381 | 610 | 0.24/0.97 |

| GenCall | 519 | 33 | 361 | 287 | 0.64/0.92 |

| optiCall | 650 | 92 | 302 | 156 | 0.81/0.77 |

| Manual | 806 | 0 | 394 | 0 | 1.00/1.00 |

| Caller . | TP . | FP . | TF . | False-fail . | Sensitivity/specificity . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illuminus | 574 | 260 | 134 | 232 | 0.71/0.34 |

| GenoSNP | 196 | 13 | 381 | 610 | 0.24/0.97 |

| GenCall | 519 | 33 | 361 | 287 | 0.64/0.92 |

| optiCall | 650 | 92 | 302 | 156 | 0.81/0.77 |

| Manual | 806 | 0 | 394 | 0 | 1.00/1.00 |

TP, manual pass and algorithm pass. FP, manual fail and algorithm pass. TF, manual fail and algorithm fail. False-fail = manual pass and algorithm fail.

| Caller . | TP . | FP . | TF . | False-fail . | Sensitivity/specificity . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illuminus | 574 | 260 | 134 | 232 | 0.71/0.34 |

| GenoSNP | 196 | 13 | 381 | 610 | 0.24/0.97 |

| GenCall | 519 | 33 | 361 | 287 | 0.64/0.92 |

| optiCall | 650 | 92 | 302 | 156 | 0.81/0.77 |

| Manual | 806 | 0 | 394 | 0 | 1.00/1.00 |

| Caller . | TP . | FP . | TF . | False-fail . | Sensitivity/specificity . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illuminus | 574 | 260 | 134 | 232 | 0.71/0.34 |

| GenoSNP | 196 | 13 | 381 | 610 | 0.24/0.97 |

| GenCall | 519 | 33 | 361 | 287 | 0.64/0.92 |

| optiCall | 650 | 92 | 302 | 156 | 0.81/0.77 |

| Manual | 806 | 0 | 394 | 0 | 1.00/1.00 |

TP, manual pass and algorithm pass. FP, manual fail and algorithm pass. TF, manual fail and algorithm fail. False-fail = manual pass and algorithm fail.

For the sampled data optiCall yielded the highest sensitivity, but with a lower specificity compared to GenCall and GenoSNP. GenoSNP's sensitivity was significantly lower than its counterparts, as was Illuminus' specificity. Anecdotally, many of GenoSNP's FFs occurred at SNPs where intensity data were shifted from the expected positions, a drawback of the within-individual clustering approach.

R-squared values (Pearson correlation coefficient where genotypes are placed on a 0, 1, 2 scale and unknown genotypes are assigned the numerical mean genotype) to the manual calls for TP SNPs were high across all three callers (0.995 for Illuminus, 0.983 for GenoSNP, 0.990 for GenCall and optiCall), suggesting that SNPs passing QC are called accurately by all algorithms.

3.2 Missed rare variants

Genetic association studies are increasingly focusing on identifying rare variation underlying disease susceptibility (Manolio et al., 2009). To investigate how well each of the algorithms captures such variants, we randomly selected 600 SNPs that were monomorphic in one algorithm but had a minor allele frequency between 4×10−4 and 0.01 in at least another two. Manual calling was carried out as described in Section 3.1. Of the 600 manually called SNPs, Illuminus misclassified 354 rare SNPs as monomorphic, while GenoSNP, GenCall and optiCall misclassified only 3, 13 and 1, respectively. This high number of misclassified rare variants is a direct consequence of Illuminus' within SNP, across sample, approach to genotype calling.

3.3 Comparison to manually called genotypes across chromosome 21

To assess how well each of the algorithms performed across a random selection of SNPs on the Immunochip, we manually called the 1868 SNPs on chromosome 21 using the same procedure as outlined in Section 3.1. Again, SNPs with a call rate <0.98 and/or HWE P<10−5 were deemed to have failed QC. QC results from the genotype-calling algorithms were then compared to those from the manually called genotypes. Although less pronounced than previous comparisons, which specifically focused on SNPs at which the genotype-calling algorithms disagreed, the same general trends were observed (Table 3). Of the 1810 SNPs passing QC in the manually called data, optiCall passed the most (1785 with a sensitivity of 0.99) and GenoSNP the least (1668 with a sensitivity of 0.92). GenCall and Illuminus lay in between (GenCall passing 1737 SNPs and Illuminus 1761, with sensitivities of 0.96 and 0.97, respectively). GenoSNP and optiCall did not misclassify any of the low-frequency SNPs as monomorphic, while GenCall misclassified just one and Illuminus misclassified 21. As expected, SNPs correctly passing QC and then correctly called polymorphic for each algorithm have highly concordant calls to the manual call set (r2>0.993 for all callers).

| Caller . | QC . | Monomorphic SNPs (of which rare misses) . | Mean r2 to manual calls . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | TP . | FP . | TF . | FF . | Sensitivity/specificity . | . | . |

| Illuminus | 1761 | 25 | 33 | 49 | 0.97/0.57 | 164 (21) | 0.993 |

| GenoSNP | 1668 | 2 | 56 | 142 | 0.92/0.97 | 85 (0) | 0.996 |

| GenCall | 1737 | 7 | 51 | 73 | 0.96/0.88 | 173 (1) | 0.997 |

| Optical | 1785 | 14 | 44 | 25 | 0.99/0.76 | 172 (0) | 0.997 |

| Manual | 1810 | 0 | 58 | 0 | 1.00/1.00 | 188 (0) | 1.000 |

| Caller . | QC . | Monomorphic SNPs (of which rare misses) . | Mean r2 to manual calls . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | TP . | FP . | TF . | FF . | Sensitivity/specificity . | . | . |

| Illuminus | 1761 | 25 | 33 | 49 | 0.97/0.57 | 164 (21) | 0.993 |

| GenoSNP | 1668 | 2 | 56 | 142 | 0.92/0.97 | 85 (0) | 0.996 |

| GenCall | 1737 | 7 | 51 | 73 | 0.96/0.88 | 173 (1) | 0.997 |

| Optical | 1785 | 14 | 44 | 25 | 0.99/0.76 | 172 (0) | 0.997 |

| Manual | 1810 | 0 | 58 | 0 | 1.00/1.00 | 188 (0) | 1.000 |

Monomorphic SNPs = the number of SNPs a genotype-calling algorithm calls monomorphic from its TPs, with the subset of missed rare variants (when compared to manual calls) shown in brackets. r2 is as in Section 3.1 and is calculated over the true QC pass SNPs which were polymorphic according to both the caller and the manual calls.

| Caller . | QC . | Monomorphic SNPs (of which rare misses) . | Mean r2 to manual calls . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | TP . | FP . | TF . | FF . | Sensitivity/specificity . | . | . |

| Illuminus | 1761 | 25 | 33 | 49 | 0.97/0.57 | 164 (21) | 0.993 |

| GenoSNP | 1668 | 2 | 56 | 142 | 0.92/0.97 | 85 (0) | 0.996 |

| GenCall | 1737 | 7 | 51 | 73 | 0.96/0.88 | 173 (1) | 0.997 |

| Optical | 1785 | 14 | 44 | 25 | 0.99/0.76 | 172 (0) | 0.997 |

| Manual | 1810 | 0 | 58 | 0 | 1.00/1.00 | 188 (0) | 1.000 |

| Caller . | QC . | Monomorphic SNPs (of which rare misses) . | Mean r2 to manual calls . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | TP . | FP . | TF . | FF . | Sensitivity/specificity . | . | . |

| Illuminus | 1761 | 25 | 33 | 49 | 0.97/0.57 | 164 (21) | 0.993 |

| GenoSNP | 1668 | 2 | 56 | 142 | 0.92/0.97 | 85 (0) | 0.996 |

| GenCall | 1737 | 7 | 51 | 73 | 0.96/0.88 | 173 (1) | 0.997 |

| Optical | 1785 | 14 | 44 | 25 | 0.99/0.76 | 172 (0) | 0.997 |

| Manual | 1810 | 0 | 58 | 0 | 1.00/1.00 | 188 (0) | 1.000 |

Monomorphic SNPs = the number of SNPs a genotype-calling algorithm calls monomorphic from its TPs, with the subset of missed rare variants (when compared to manual calls) shown in brackets. r2 is as in Section 3.1 and is calculated over the true QC pass SNPs which were polymorphic according to both the caller and the manual calls.

By combining the FF rate and the number of misclassified rare variants across each genotype-calling algorithm, the loss percentages over the 1868 SNPs of chromosome 21 are 3.87, 7.85, 4.09 and 1.38% for Illuminus, GenoSNP, GenCall and optiCall, respectively. Extending this result over the entire Immunochip, we estimate that 7440, 15 094, 7865 and 2657 ‘callable’ SNPs will be falsely removed from analysis using Illuminus, GenoSNP, GenCall and optiCall, respectively.

4 DISCUSSION

Complex disease genetic association studies are increasingly focusing on rare and low-frequency variants, either using off-the-shelf genome-wide products such as the Illumina HumanOmni5-Quad or mass-produced targeted custom arrays such as the Metabochip, Immunochip or Exomechip. To improve genotype calling for such arrays, we have developed a new algorithm, optiCall, which uses both within and across sample intensity data when calling genotypes. Considering both sets of information simultaneously means optiCall captures the rare and low-frequency variants some purely SNP-wise genotype-calling algorithms can miss, while remaining robust to genotype intensity clouds lying away from their expected positions. Given that the allelic probes on custom arrays have undergone less stringent QC compared to those that make it onto mass-produced genome-wide SNP arrays, the ability to correctly call such SNPs can greatly increase the number of SNPs passing QC (and thus increase power to detect association).

We have shown that, of the existing genotype-calling algorithms, optiCall has the highest sensitivity in terms of SNPs passing basic QC. This is significant because each SNP that is removed from a study due to poor genotype calling is potentially a missed association. Furthermore, with reduced linkage disequilibrium observed at rare and low-frequency SNPs (in comparison to common variants), it is less likely that an association to such a variant will be detected through additional tag SNPs. This increase in sensitivity does also yield a small decrease in specificity but, given that cluster plots of associated variants can be manually checked prior to embarking on replication studies, the consequences of this in terms of false-positive associations are likely minimal.

Unlike some existing genotype-calling algorithms, optiCall estimates the positions of the genotype classes using the given intensity data and does not require a training dataset or predefined cluster file. This removes genotype-calling errors that manifest through differences between the training dataset and that under study. As more studies attempt to jointly analyze data from different genotyping laboratories and across many different ethnicities, such errors have the possibility to not only reduce power but also to increase false-positive associations. When using optiCall, we recommend that divergent populations (such as African-Americans and white Europeans) be called separately so population specific within and across sample priors are used. Some existing calling-algorithms allow users to manually re-position the predefined clusters to better match discordant datasets whereas optiCall automates this potentially labor intensive procedure. Importantly, optiCall's use of both within and across sample intensity data ensures it is more robust to small sample sizes than mixture model-based algorithms that only use SNP-wise data. Recently, Li et al. (2012) published a genotype-calling algorithm for the Illumina platform, M3, that also uses both within and across sample information when making genotype calls. M3 runs a two-step calling process. The first step involves calling across sample, and then selecting a set of possibly poorly called SNPs (based on call rate and minor allele frequency) to call using across SNP information. optiCall differs from M3 in that it makes genotype calls using both within and across sample information simultaneously. M3 is written in Matlab, and we did not possess the necessary software to make a quantitative comparison.

A drawback of optiCall's genotype-calling approach is that it is very sensitive to intensity outliers (because these prevent the mixture models from fitting well). If no intensity outlier removal is performed prior to running optiCall, we recommend running optiCall's built in outlier removal. This process calculates the mean intensity difference x(1)−x(2) over SNPs for each sample and those with a mean intensity difference more than 2 SD away from the mean are removed before genotype calling.

In summary, we have developed a new genotype-calling algorithm for Illumina arrays that uses both SNP-wise and sample-wise calling to more accurately ascertain genotypes at rare, low-frequency and common variants, even when genotype intensity clouds are shifted from their expected positions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Luke Jostins and Andrew Morris for helpful comments on the algorithm and manuscript. We also thank Rob Andrews and Hannah Blackburn for providing genotype calls from Illuminus, GenoSNP and GenCall. We acknowledge the WTCCC2, 1958 British Cohort and the Immunochip consortium for access to samples and genotype data.

Funding: This work is funded by a grant from the Wellcome Trust (098051).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Associate Editor: Prof. Martin Bishop