-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Michael J Stein, Darren Smith, Christopher Chia, Alan Matarasso, Paradoxical Adipose Hyperplasia Following Cryolipolysis, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 44, Issue 10, October 2024, Pages 1063–1071, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjae077

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Cryolipolysis (CL) is a noninvasive technique in which applicators cool tissue to temperatures that selectively destroy adipocytes. Since its introduction to the market, it has rapidly become one of the leading nonsurgical modalities to reduce fat in the aesthetic industry. Paradoxical adipose hyperplasia (PAH) is a rare adverse reaction to CL, in which there is initial reduction in fat volume, followed by abnormal fat growth exceeding the original volume in the treated area. The incidence of PAH is thought to be underreported, and its pathophysiology and management remains unclear. The objective of this study was to present a series of PAH cases and review efficacy of management modalities.

Cryolipolysis (CL) is a common noninvasive fat-reducing procedure performed by a wide array of aesthetic practitioners in an office-based setting. The technique was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2010 and has since been administered for the treatment of chin, upper arms, abdomen/flank, back, inner/outer thighs, and under buttock. The mechanism of action of CL is predicated on the selective apoptosis of adipocytes relative to surrounding cells when subjected to certain temperatures.1,2 An applicator is placed on the targeted fat and the device gradually cools the tissue to a target temperature of 30.2°F. Due to the lack of resistance of adipocytes at this target temperature they undergo apoptosis and over weeks to months are phagocytosed and cleared by macrophages.3,4

CL is considered a safe, low-risk procedure in appropriately selected patients. One systematic review examining the CL safety and efficacy profile reported mild adverse events (erythema, pain, edema, dysaesthesia) occurring at a rate of 0.82%; and moderate adverse events: vasovagal events (0.07%), visible contour irregularities (0.14%), and puritis and bloating (0.07%).5 No severe complications of CL were reported.

In 2014 a case of paradoxical adipose hyperplasia (PAH) first surfaced from Jaalian et al who presented a 41-year-old male patient who underwent a single cycle of CL to his abdomen and presented 3 months later with a sharply demarcated subcutaneous mass where the applicator was applied.6 The tissue growth occurred gradually and stabilized at 5 months. Two more case reports followed in 2014 by Macedo and Raphael, painting a similar clinical picture and establishing the entity of PAH, a condition of abnormal fat growth in response to CL.7,8 Four case series in 2015 and 3 in 2016 followed.9-15 A systematic review in 2017 that included all published cases of PAH suggested that there may be a gender or genetic correlation.16 The authors also pointed out that the applicator's size may contribute to its development, because PAH was more common with large applicators. In 2021 a multicenter study of 8 Canadian medical centers reviewed 2114 patients who received CL and discovered 9 patients with PAH. The authors noted that the incidence rate of between 0.05% and 0.39% was notably higher than the previously reported rate of 0.025%.17 Interestingly, most cases (77%) were associated with an older CS applicator and incidence rates at all sites were reduced by over 75% when the newer CS model was instituted. A recent study in 2023 reporting on the efficacy of cryolipolysis noted no adverse events.18

The incidence of PAH may be underreported due to the perception amongst patients that they simply gained weight after the procedure. Furthermore, there is tremendous variability in location and provider performing the procedure, leading to inconsistent reporting. Also, cases are reported based on the number of patients rather than number of body areas treated with CL (for instance, 1 patient treated in 4 areas may have 3 areas of PAH, all of which should be recorded as independent adverse events).

The lack of understanding of underlying PAH pathophysiology, as well as the lack of consensus on management, is concerning, considering CL is the fourth most frequent noninvasive cosmetic procedure in the United States, with progressive growth since 2013.19,20 The objective of the current study was to present a large series of PAH cases and review therapeutic approaches.

METHODS

A multicenter retrospective review of PAH cases was performed by 4 New York–based, American Board of Plastic Surgery–certified plastic surgeons. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Data included patient demographics, number and location of treatments, time to development of PAH, management of PAH, and success of management. The impetus for the study was an increase in the number of PAH cases being reported at morbidity and mortality rounds, prompting the 4 authors to retrospectively analyze their own PAH cases over the previous calendar year. To perform the retrospective review, a list of cases in each surgeon's practice was queried for the word “paradoxical adipose hyperplasia.” Extracted cases were then pooled for analysis.

The data points collected included age, sex, number of CL sessions, location of CL treatment, and patient-reported time from CL treatment to development of PAH. With respect to the treatment of PAH, the modality of PAH treatment and the number of treatments and sites were recorded. To standardize the outcome reporting between the participating surgeons, 3 efficacy outcome groups were created: “not improved,” “improved,” and “completely resolved.” Improved indicated that the overall contour was improved yet still noticeable and more palpable than surrounding untreated areas. Completely resolved was defined as unnoticeable on inspection or palpation.

RESULTS

Patient Cohort

Thirty-three patients and 60 sites of PAH were identified from June 2022 to June 2023 (Table 1). All cases were self-referred by the patient and 20 (85%) were female, with an average age of 41 (range 24-61). Of the 64% of patients who reported the number of CL treatments, the average number was 2. Patients presented to the treating surgeons from various clinics, so unfortunately there was no information on CL manufacturer, settings, whether it was an older or newer model, or the type and size of applicator. Of the 60 sites of PAH identified in this cohort, the most common location of CL was the abdomen (42%, 25/60) followed by flank (30%, 18/60); axilla (7%, 4/60); inner thighs (7%, 4/60); back (7%, 4/60); submentum (3%, 2/60); and arms (3%, 2/60). The average reported time to PAH development was 3 months (range 0-8 months), based on 21 patients with available data. All patients in the cohort paid in full for their surgical procedure from their surgeon. Data on reimbursement to the patient or surgeon from the CL company was not collected.

| Case . | Age . | Sex . | No. CL treatments before presentation to surgeon . | Location of CL treatment . | Time from CL to PAH (months) . | PAH treatment . | No. PAH treatments . | Success of treatment (not improved, improved, resolved) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 55 | F | NA | Abdomen Flank Flank Submentum Back flank Back flank Arm Arm | NA | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 2 | 54 | F | 2 | Abdomen Flank Flank | 2 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 3 | 35 | F | 1 | Flank Flank | 5 | VASER/PAL | 3 | Improved |

| 4 | 45 | F | NA | Abdomen Flank Flank | NA | VASER/PAL | 3 | Resolved |

| 5 | 45 | F | 1 | Abdomen Flank Flank Inner thigh Inner thigh | 0 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 6 | 24 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 7 | 49 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 2 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 8 | 28 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 9 | 42 | F | 2 | Abdomen Flank Flank | 2 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 10 | 61 | F | 3 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 11 | 31 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 3 | Improved |

| 12 | 26 | F | 2 | Abdomen | 2 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 13 | 33 | M | 2 | Abdomen | 2 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Improved |

| 14 | 37 | M | 1 | Flank Flank | 1.5 | VASER/PAL | 1 | NA |

| 15 | 44 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 16 | 55 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 17 | 45 | F | 2 | Submentum/chin | 2 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 18 | 45 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 19 | 52 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Improved |

| 20 | 41 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 21 | 33 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 22 | 32 | F | NA | Axilla Axilla | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 23 | 37 | M | NA | Flank Flank | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 24 | 33 | F | NA | Submentum | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Improved |

| 25 | 35 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 26 | 61 | F | 3 | Abdomen Axilla Axilla | 6 | PAL Abdominoplasty | 1 | Resolved |

| 27 | 30 | F | 2 | Inner thigh Inner thigh | 3 | PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 28 | 34 | F | 2 | Flank Flank | 6 | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Improved |

| 29 | 38 | M | 2 | Abdomen | 4 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 30 | 52 | M | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 31 | 24 | F | 2 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 32 | 34 | F | 4 | Abdomen | 8 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 33 | 54 | F | 4 | Abdomen Back roll Back roll | 6 | PAL | NA | Improved |

| Case . | Age . | Sex . | No. CL treatments before presentation to surgeon . | Location of CL treatment . | Time from CL to PAH (months) . | PAH treatment . | No. PAH treatments . | Success of treatment (not improved, improved, resolved) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 55 | F | NA | Abdomen Flank Flank Submentum Back flank Back flank Arm Arm | NA | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 2 | 54 | F | 2 | Abdomen Flank Flank | 2 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 3 | 35 | F | 1 | Flank Flank | 5 | VASER/PAL | 3 | Improved |

| 4 | 45 | F | NA | Abdomen Flank Flank | NA | VASER/PAL | 3 | Resolved |

| 5 | 45 | F | 1 | Abdomen Flank Flank Inner thigh Inner thigh | 0 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 6 | 24 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 7 | 49 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 2 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 8 | 28 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 9 | 42 | F | 2 | Abdomen Flank Flank | 2 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 10 | 61 | F | 3 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 11 | 31 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 3 | Improved |

| 12 | 26 | F | 2 | Abdomen | 2 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 13 | 33 | M | 2 | Abdomen | 2 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Improved |

| 14 | 37 | M | 1 | Flank Flank | 1.5 | VASER/PAL | 1 | NA |

| 15 | 44 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 16 | 55 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 17 | 45 | F | 2 | Submentum/chin | 2 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 18 | 45 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 19 | 52 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Improved |

| 20 | 41 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 21 | 33 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 22 | 32 | F | NA | Axilla Axilla | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 23 | 37 | M | NA | Flank Flank | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 24 | 33 | F | NA | Submentum | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Improved |

| 25 | 35 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 26 | 61 | F | 3 | Abdomen Axilla Axilla | 6 | PAL Abdominoplasty | 1 | Resolved |

| 27 | 30 | F | 2 | Inner thigh Inner thigh | 3 | PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 28 | 34 | F | 2 | Flank Flank | 6 | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Improved |

| 29 | 38 | M | 2 | Abdomen | 4 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 30 | 52 | M | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 31 | 24 | F | 2 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 32 | 34 | F | 4 | Abdomen | 8 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 33 | 54 | F | 4 | Abdomen Back roll Back roll | 6 | PAL | NA | Improved |

CL, cryolipolysis; NA, not available; PAH, paradoxical adipose hyperplasia; PAL, power-assisted liposuction; VASER, vibration amplification of sound energy at resonance.

| Case . | Age . | Sex . | No. CL treatments before presentation to surgeon . | Location of CL treatment . | Time from CL to PAH (months) . | PAH treatment . | No. PAH treatments . | Success of treatment (not improved, improved, resolved) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 55 | F | NA | Abdomen Flank Flank Submentum Back flank Back flank Arm Arm | NA | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 2 | 54 | F | 2 | Abdomen Flank Flank | 2 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 3 | 35 | F | 1 | Flank Flank | 5 | VASER/PAL | 3 | Improved |

| 4 | 45 | F | NA | Abdomen Flank Flank | NA | VASER/PAL | 3 | Resolved |

| 5 | 45 | F | 1 | Abdomen Flank Flank Inner thigh Inner thigh | 0 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 6 | 24 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 7 | 49 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 2 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 8 | 28 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 9 | 42 | F | 2 | Abdomen Flank Flank | 2 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 10 | 61 | F | 3 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 11 | 31 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 3 | Improved |

| 12 | 26 | F | 2 | Abdomen | 2 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 13 | 33 | M | 2 | Abdomen | 2 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Improved |

| 14 | 37 | M | 1 | Flank Flank | 1.5 | VASER/PAL | 1 | NA |

| 15 | 44 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 16 | 55 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 17 | 45 | F | 2 | Submentum/chin | 2 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 18 | 45 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 19 | 52 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Improved |

| 20 | 41 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 21 | 33 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 22 | 32 | F | NA | Axilla Axilla | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 23 | 37 | M | NA | Flank Flank | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 24 | 33 | F | NA | Submentum | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Improved |

| 25 | 35 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 26 | 61 | F | 3 | Abdomen Axilla Axilla | 6 | PAL Abdominoplasty | 1 | Resolved |

| 27 | 30 | F | 2 | Inner thigh Inner thigh | 3 | PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 28 | 34 | F | 2 | Flank Flank | 6 | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Improved |

| 29 | 38 | M | 2 | Abdomen | 4 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 30 | 52 | M | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 31 | 24 | F | 2 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 32 | 34 | F | 4 | Abdomen | 8 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 33 | 54 | F | 4 | Abdomen Back roll Back roll | 6 | PAL | NA | Improved |

| Case . | Age . | Sex . | No. CL treatments before presentation to surgeon . | Location of CL treatment . | Time from CL to PAH (months) . | PAH treatment . | No. PAH treatments . | Success of treatment (not improved, improved, resolved) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 55 | F | NA | Abdomen Flank Flank Submentum Back flank Back flank Arm Arm | NA | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 2 | 54 | F | 2 | Abdomen Flank Flank | 2 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 3 | 35 | F | 1 | Flank Flank | 5 | VASER/PAL | 3 | Improved |

| 4 | 45 | F | NA | Abdomen Flank Flank | NA | VASER/PAL | 3 | Resolved |

| 5 | 45 | F | 1 | Abdomen Flank Flank Inner thigh Inner thigh | 0 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 6 | 24 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 7 | 49 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 2 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 8 | 28 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 9 | 42 | F | 2 | Abdomen Flank Flank | 2 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 10 | 61 | F | 3 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 11 | 31 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 3 | Improved |

| 12 | 26 | F | 2 | Abdomen | 2 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 13 | 33 | M | 2 | Abdomen | 2 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Improved |

| 14 | 37 | M | 1 | Flank Flank | 1.5 | VASER/PAL | 1 | NA |

| 15 | 44 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL | 1 | Resolved |

| 16 | 55 | F | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 2 | Resolved |

| 17 | 45 | F | 2 | Submentum/chin | 2 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 18 | 45 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 19 | 52 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Improved |

| 20 | 41 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 21 | 33 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 22 | 32 | F | NA | Axilla Axilla | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 23 | 37 | M | NA | Flank Flank | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 24 | 33 | F | NA | Submentum | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Improved |

| 25 | 35 | F | NA | Abdomen | NA | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Resolved |

| 26 | 61 | F | 3 | Abdomen Axilla Axilla | 6 | PAL Abdominoplasty | 1 | Resolved |

| 27 | 30 | F | 2 | Inner thigh Inner thigh | 3 | PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 28 | 34 | F | 2 | Flank Flank | 6 | VASER/PAL/BodyTite | 1 | Improved |

| 29 | 38 | M | 2 | Abdomen | 4 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 30 | 52 | M | 1 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 31 | 24 | F | 2 | Abdomen | 3 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 32 | 34 | F | 4 | Abdomen | 8 | VASER/PAL | 1 | Improved |

| 33 | 54 | F | 4 | Abdomen Back roll Back roll | 6 | PAL | NA | Improved |

CL, cryolipolysis; NA, not available; PAH, paradoxical adipose hyperplasia; PAL, power-assisted liposuction; VASER, vibration amplification of sound energy at resonance.

Treatment

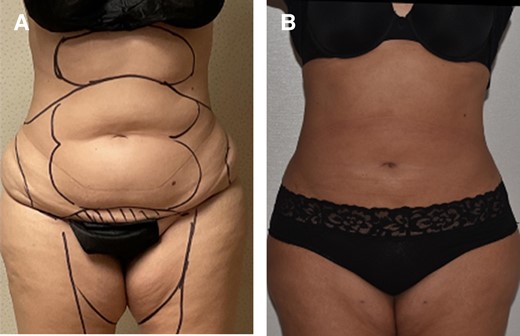

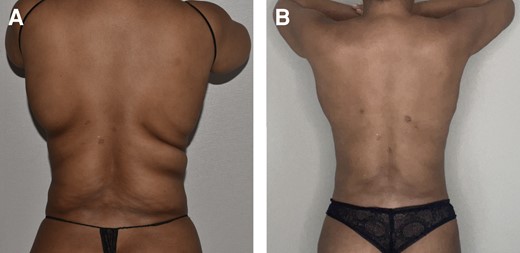

All PAH cases were treated with power-assisted liposuction (Microaire Surgical Instruments LLC, Charlottesville, VA) in isolation or with 1 or more adjuncts including VASER (vibration amplification of sound energy at resonance); BodyTite (InMode, Lake Frost, CA); or full abdominoplasty. Most PAH cases were treated with VASER power-assisted liposuction (PAL) (21/33, 64%) followed by VASER PAL with BodyTite (9/33, 27%). PAL was administered in isolation in 2 cases (6%), and full abdominoplasty was added to PAL in 1 case (3%). One PAH treatment was required for 72% of cases, while 28% of cases required multiple rounds of intervention (range 2-3) to see improvement. There were no reported refractory PAH cases; 47% cases improved (15/32) and 53% (17/32) of cases completely resolved (Figures 1-3). One case was lost to follow-up, and the efficacy of treatment was not evaluated.

Before (A) and after (B) photographs of 40-year-old patient with moderate fibrosis (palpable firmness of treated area, notably harder than surrounding untreated subcutaneous fat) who was effectively treated with VASER PAL. PAH, paradoxical adipose hyperplasia; PAL, power-assisted liposuction; VASER, vibration amplification of sound energy at resonance.

Before (A, B, D, F) and after (C, E, G) photographs of 60-year-old patient with severe and painful fibrosis (palpable and tender firmness with mass effect and abdominal fat distortion) who was treated with PAL-assisted full abdominoplasty. PAH, paradoxical adipose hyperplasia; PAL, power-assisted liposuction.

Before (A) and after (B) photographs of 45-year-old patient with moderately fibrotic PAH to flanks who was effectively treated with VASER PAL. PAH, paradoxical adipose hyperplasia; PAL, power-assisted liposuction; VASER, vibration amplification of sound energy at resonance.

Morphologic Histological Analysis

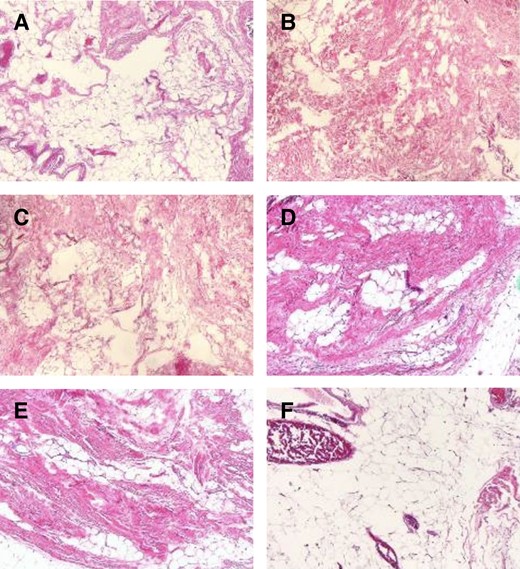

One tissue specimen from a PAH case treated with abdominoplasty was available for histological examination by a pathologist. This 60-year-old patient had symptomatic masses to the upper and lower abdomen in the same applicator distribution following 6 rounds of CL. She was treated with PAL, followed by full abdominoplasty (Figure 2). Intraoperatively the pannus was split longitudinally for gross morphologic analysis and the enlarged area was notably firmer to palpation than the lateral pannus, which was not treated with CL. Sections of the abdominal pannus were taken for pathologic evaluation, however unfortunately the pathologist took random sections without description of location. However, the available histology reveals sections with a clear area of fibrosis surrounded by normal fibroadipose tissue. The pathology report noted, “bland fibrous tissue coursing through unremarkable adipose tissues. The bands of fibrous tissues are haphazardly arranged, entrapping pockets of adipose tissue. The fibrous tissue is composed of spindle cells with no evidence of increased mitotic rate or cytologic atypia and, therefore, appears to be benign” (Figure 4).

Histology slide. Per pathology report, (A, B, and C) show normal fat. Bands of bland fibrous tissue course through unremarkable adipose tissue. (D, E, and F) show fibrotic (presumed PAH) area. The bands of fibrous tissue are haphazardly arranged, entrapping pockets of adipose tissue. The fibrous tissue is composed of spindle cells with no evidence of increased mitotic rate or cytologic atypia and, therefore, appears to be benign. PAH, paradoxical adipose hyperplasia.

DISCUSSION

Issues With Minimally Invasive Technologies Provided by Non-Plastic (and Nonmedical) Personnel

The demand for nonsurgical body contouring is on the rise. This demand has been met by an increase in energy-based devices targeting fat reduction. Like neuromodulators and fillers, these minimally invasive treatments are often administered by non–board-certified plastic surgeons or mid-level providers. These devices are largely considered low risk and are strategically designed so machine automation facilitates easy and efficient execution by nonmedical personnel. Today, cryolipolysis is offered in med spas, aesthetician offices, massage parlors, and other freestanding offices not necessarily overseen by a medical doctor, or overseen by a medical doctor off-site who may not be available to examine patients. Moreover, when the machines are marketed to plastic surgeons themselves, the model is such that any ancillary staff, including nonmedical personnel, can safely operate the machine independently without oversight from the surgeon.

The shortcomings of this model are 3-fold. First, the rigors of a fully informed consent process may not be met with respect to disclosing the risks, alternatives, and consequences of complications. Similar to the acknowledgment of breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) or breast implant illness (BII) in the context of implant placement, perhaps so too should PAH be disclosed every time cryolipolysis be performed. Furthermore, a registry could exist to encourage public reporting of PAH and learn more about demographic and device contributing factors.

Second, nonmedical providers may not have the skill to recognize and treat the complications of cryolipolysis. Heterogenous presentations of PAH make its diagnosis and management difficult, even for a board-certified plastic surgeon experienced in treating PAH. Moreover, if a patient treated by an aesthetician develops PAH and returns to their office, it is likely that, even if diagnosed correctly, they may be treated with more minimally invasive modalities because these are the only tools offered in the office. This was observed by surgeons in our cohort. Patient 27, for instance, was a 30-year-old female treated with CL to the inner thighs at a med spa and developed PAH. The patient subsequently underwent another round of CL and then 2 rounds of deoxycholic acid injections to the inner thighs before presenting on their own volition to the surgeon for a second opinion.

The third shortcoming has to do with documentation. It is possible that PAH remains underreported by practioners and manufacturers. Whether it is the perception of patients that they simply gained weight after their procedure, misdiagnosis by a caregiver who lacks experience diagnosing PAH, or the lack of documenting PAH cases altogether, it is possible that PAH is a more common entity than reported in the literature. A paucity of studies address what should be considered an important complication of cryolipolysis. Also, studies report the number of patients instead of the numbers of areas treated, which underestimates the true incidence of PAH. A 2022 study by Cox et al included a scoping review of PAH cases published in the literature and reported only 65 cases to date, in addition to their case series of 4 patients.21 The present study spanning only 1 year by 4 surgeons reports 60 new sites of PAH in 33 patients. Increased recognition of this complication by enhanced reporting and patient education will likely continue to reveal more cases, as patients who were treated by nonmedical practitioners learn to recognize its presentation. This has already begun to happen, with model Linda Evangelista speaking out about her struggles with PAH in a New York Times 2021 article, and with the follow up New York Times articles in April 2023 discussing PAH underreporting.22–24

The unfortunateirony of PAH is that these patients were seeking nonsurgical solutions for their problem areas and ultimately required surgery to rectify the problem.

Diagnosis and Treatment

PAH is capricious. There is striking heterogeneity with respect to the factors that contribute to PAH (eg, machine type, older vs new model, energy level, size of applicator, number of treatments, gender, patient genetics) as well as its clinical presentation (eg, hard or soft, painful or not, restriction to breathing, degree of fat hypertrophy). The randomness of its occurrence is also apparent. Patients may have 5 areas treated with CL but only 3 that develop PAH. Some patients with multiple areas of PAH have palpably hard zones and other zones of PAH that are soft. Some PAH areas are well circumscribed to the shape of the applicator, while others have irregular borders.

For these reasons PAH has eluded formal classification and management algorithms to date. In the literature, management of PAH includes conservative management (18.5%); deoxycholic acid injections (1.5%); additional cycles of cryolipolysis (3.1%); monopolar radiofrequency ablation (1.5%); liposuction (66.2%); panniculectomy (1.5%); abdominoplasty (1.5%); and staged lipoabdominoplasty (1.5%).21

To diagnose PAH, the authors propose the following criteria. The patient must have a history of CL and 1 or more of the following in the area of CL treatment: (1) a new fat deposit of different size or consistency than the surrounding area; (2) firmness to palpation; (3) the area remains resistant to weight loss.

The authors provide a treatment algorithm (Table 2), although caution surgeons that it should be applied as a conceptual framework, because it is limited by the variability and capriciousness of PAH presentation. The degree of fibrosis dictates whether technological adjuncts such as VASER and BodyTite should assist with the PAL, and the degree of skin laxity dictates whether an excisional procedure is warranted.

| Diagnosis . | Mild PAH (Class I PAH) . | Moderate to Severe PAH (Class II PAH) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | IA No skin excess | IB Mild skin excess | IC Moderate/severe skin excess | IIA No skin excess | IIB Mild skin excess | IIC Moderate/severe skin excess |

| PAL | PAL + BodyTite | PAL + abdominoplasty | VASER PAL | VASER PAL + BodyTite | PAL + BodyTite + abdominoplasty | |

| Diagnosis . | Mild PAH (Class I PAH) . | Moderate to Severe PAH (Class II PAH) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | IA No skin excess | IB Mild skin excess | IC Moderate/severe skin excess | IIA No skin excess | IIB Mild skin excess | IIC Moderate/severe skin excess |

| PAL | PAL + BodyTite | PAL + abdominoplasty | VASER PAL | VASER PAL + BodyTite | PAL + BodyTite + abdominoplasty | |

PAH, paradoxical adipose hyperplasia; PAL, power-assisted liposuction; VASER, vibration amplification of sound energy at resonance.

| Diagnosis . | Mild PAH (Class I PAH) . | Moderate to Severe PAH (Class II PAH) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | IA No skin excess | IB Mild skin excess | IC Moderate/severe skin excess | IIA No skin excess | IIB Mild skin excess | IIC Moderate/severe skin excess |

| PAL | PAL + BodyTite | PAL + abdominoplasty | VASER PAL | VASER PAL + BodyTite | PAL + BodyTite + abdominoplasty | |

| Diagnosis . | Mild PAH (Class I PAH) . | Moderate to Severe PAH (Class II PAH) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | IA No skin excess | IB Mild skin excess | IC Moderate/severe skin excess | IIA No skin excess | IIB Mild skin excess | IIC Moderate/severe skin excess |

| PAL | PAL + BodyTite | PAL + abdominoplasty | VASER PAL | VASER PAL + BodyTite | PAL + BodyTite + abdominoplasty | |

PAH, paradoxical adipose hyperplasia; PAL, power-assisted liposuction; VASER, vibration amplification of sound energy at resonance.

The authors also emphasize that liposuction of a PAH patient may not be “garden-variety” liposuction, or even revisional liposuction, for that matter. The architectural fibrosis that occurs secondary to PAH is unique and complex and likely has reduced vascularity. The authors suggest that surgeons approach with caution those with moderate skin laxity and PAH in the supraumbilical area. In these patients an abdominoplasty must be approached carefully due to the theoretical chance of increased wound healing complications within the fibrotic watershed area. This area is known as the “terrible abdominoplasty triangle” in lipoabdominoplasty.25 In general, it is the area most in danger of ischemia due to its devascularization, and potentially more so in patients previously treated with energy devices or cryolipolysis.

Study Limitations

The study is limited by the size and quality of the data. Most notably, the data indicating the interval between CL treatment and PAH management was subjectively reported by patients. Furthermore, heterogeneity likely existed in treatment device, health center, and settings, and there was no way for the participating surgeons to extract this data. Patients may even have received CL from a non–FDA-approved device, and there would be no way for the participating surgeons to identify this. Previous authors have also alluded to the possibility that PAH is far less common with newer CL models.17 This could very well be true, yet was impossible to investigate in the current study. Confirmation bias was also possible with respect to surgeon-specific PAH treatment. While all surgeons had the same technological adjuncts available for treatment, it is possible that some surgeons gravitated to energy devices due to preconceived notions of efficacy, whereas other surgeons treated their cases with power-assisted liposuction alone. Last, with respect to the diagnosis, the degree of fibrosis is hard to quantify clinically, so the choice of whether to employ an energy-based device is essentially surgeon-specific.

CONCLUSIONS

The authors present the largest series of PAH cases to date. PAH remains a rare, yet significant, complication after cryolipolysis. Accurate diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and accurate documentation of incidence per body area rather than per patient are important steps toward improving our understanding of the true incidence of this condition. As with any procedure, informed consent means explicit disclosure of this complication as well as the consequences and treatments. For patients who initially seek cryolipolysis for nonsurgical fat reduction, PAH management remains primarily surgical, and therefore PAH can be considered a major complication. Future histologic studies and clinical series will be helpful in studying the degree of fibrosis and determining whether it correlates with topographic body area, number of cycles, machine settings, or any other variables. The conceptual frameworks outlined in this study should help guide surgeons with timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Given that PAH is a capricious entity, diagnosis and management should remain flexible.

Disclosures

Dr Chirstopher Chia is a consultant for InMode (Lake Forest, CA) and Dr Darren Smith is reimbursed by InMode for promotional treatments. Dr Michael Stein and Dr Alan Matarasso have no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES

Author notes

From Manhattan Eye Ear and Throat Hospital, New York, NY, USA.