-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ivan Couto-González, Adrián Ángel Fernández-Marcos, Beatriz Brea-García, Nerea González-Giménez, Francisco Canseco-Díaz, Belén García-Arjona, Cristina Mato-Codesido, Antonio Taboada-Suárez, Silicone Shell Breast Implants in Patients Undergoing Risk-Reducing Mastectomy With a History of Breast-Conserving Surgery and Adjuvant Radiotherapy: A Long-term Study, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 44, Issue 1, January 2024, Pages NP60–NP68, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjad300

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Indications for breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy (BCSAR) in patients with breast carcinoma are increasing, as are indications for risk-reducing mastectomy (RRM) in healthy subjects. Most of these cases are reconstructed with silicone shell breast implants (SSBIs).

The aim of this work was to study complications of SSBIs in breast reconstruction in patients undergoing RRM with previous BCSAR.

A prospective cohort study was designed. The study group included cases of RRM reconstructed with SSBI in patients who had previously undergone BCSAR in the same breast. The control group consisted of patients with high-risk breast cancer who had undergone RRM and immediate SSBI reconstruction without previous BCSAR.

There was a history of BCSAR in 15.8% of cases. The first SSBI used in immediate reconstruction after RRM was replaced in 51.5% of cases with a mean [standard deviation] survival of 24.04 [28.48] months. BCSAR was significantly associated with pathological capsular contracture (P = .00) with this first SSBI (37.5% vs 5.9%). Of the cases requiring the replacement of the first SSBI, 44.23% suffered failure of the second SSBI, with a mean survival of 27.95 [26.53] months. No significant association was found between the consecutive development of capsular contracture in the second SSBI and a previous history of BCSAR (P = .10).

BCSAR prior to RRM reconstructed with an SSBI is associated with a significant increase in pathological capsular contracture. Patients should be warned of the high rate of SSBI complications and reconstruction failure. Polyurethane-coated implants may provide an alternative in cases in which alloplastic reconstruction is considered in patients with previous BCSAR.

Nowadays, many patients with primary breast cancer can benefit from breast-conserving surgery (BCS) as part of their treatment. BCS combined with adjuvant radiotherapy (BCSAR) allows for better local control of the disease1,2 and leads to an improvement in survival rates compared with patients receiving BCS alone.3 The benefits of BCSAR for the patient include psychological considerations, mainly due to a better perception of body image after surgery compared with patients undergoing mastectomy4,5 and a better overall quality of life.6 However, there are also advantages as far as an earlier recovery from surgery and greater economic efficiency are concerned.7 BCS has progressively gained in popularity from the initial studies in the late 1970s and early 1980s to the present day. Until a few years ago, mastectomy seemed to be the treatment of choice in the case of multicentric or multifocal tumors,8 tumors larger than 5 cm,9 or even when repeating BCS in cases of tumor recurrence in a breast with previous BCSAR.10 Today, however, the possibility of undergoing BCS in these conditions has allowed patients to benefit in terms of psychological well-being with a similar degree of oncological safety as a mastectomy. A greater trend towards neoadjuvant chemotherapy11 has also led to an increase in indications for BCS.12

Paradoxically, as indications for BCS and the overall number of patients undergoing this treatment are increasing, indications for mastectomy in healthy patients are also clearly on the rise.13,14 In recent years, due to better and closer medical monitoring of high-risk breast cancer patients and the widespread use of genetic testing, there has been a growing indication for risk-reducing mastectomies (RRMs). Most of these cases are immediately reconstructed with silicone shell breast implants (SSBIs), the most commonly used type of breast implant.15-17

In routine clinical practice, a growing number of patients, having undergone BCSAR, are diagnosed with an increased risk of breast cancer (mainly BRCA-1 and BRCA-2) in the months following the end of their oncological treatment. Little research has been carried out into the conversion to mastectomy in this group of patients with a previously irradiated breast and particularly into the evolution and survival of the SSBI.18,19 The aim of this study was to assess the incidence of complications and survival of SSBIs used in immediate alloplastic breast reconstruction in patients undergoing RRM with previous BCSAR in the same breast.

METHODS

A prospective case-control study was conducted between January 2015 and December 2020. Permission from the IRB of Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago de Compostela was obtained for this study. Patients included in the study signed a specific informed consent form. The study group includes cases of breast reconstructions carried out with SSBIs in patients who had previously undergone BCSAR in the same breast. The control group consists of patients with high-risk breast cancer who underwent RRM and immediate SSBI reconstruction with no previous history of BCSAR. In all the cases, the breast implants were inserted subpectorally.

Patients undergoing BCS without adjuvant radiotherapy were excluded as controls, as were those who had undergone BCSAR or mastectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy in one breast and RRM without BCSAR in the contralateral breast, due to the possible indirect influence of the administration of radiotherapy on the contralateral breast. Cases in which polyurethane-coated implants were used were also excluded from the study, as were cases in which acellular dermal matrix (ADM) was employed with the implant.

Items included in the study protocol are shown in Table 1. The data obtained were collected in a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel Office 365) and processed with SPSS Statistics 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normal distribution of quantitative variables. A t test was employed in the study of hypothesis testing for parametric distributions, after checking the equality of variances with Levene's test. In the case of nonparametric distribution, hypothesis testing was carried out by the Mann-Whitney U test. Multiple-regression analysis was performed to study the possible influence of the rest of the variables studied on the quantitative variables. In the case of qualitative variables, hypothesis testing was carried out with the χ2 test. P ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant.

| Personal data . | Level . |

|---|---|

| Age | Years |

| Smoker | Yes/no |

| BMI | Kg/m2 |

| Oncological data | |

| Location | Right/left |

| BCSAR | Yes/no |

| Tumor histology | |

| Tumor biology | |

| Oncological stage | |

| Cause of RRM | |

| RRM pattern | |

| NAC sparing | Yes/no |

| Reconstructive technique | Expander |

| Direct-to-implant | |

| Mixed techniques (flap + expander/implant) | |

| Follow-up first implant | |

| First implant reconstruction failure | Yes/no |

| Cause of first implant reconstruction failure | |

| Survival first implant | Months |

| Follow-up second implant | |

| Second implant reconstruction failure | Yes/no |

| Cause of second implant reconstruction failure | No failure |

| Survival second implant | Months |

| Personal data . | Level . |

|---|---|

| Age | Years |

| Smoker | Yes/no |

| BMI | Kg/m2 |

| Oncological data | |

| Location | Right/left |

| BCSAR | Yes/no |

| Tumor histology | |

| Tumor biology | |

| Oncological stage | |

| Cause of RRM | |

| RRM pattern | |

| NAC sparing | Yes/no |

| Reconstructive technique | Expander |

| Direct-to-implant | |

| Mixed techniques (flap + expander/implant) | |

| Follow-up first implant | |

| First implant reconstruction failure | Yes/no |

| Cause of first implant reconstruction failure | |

| Survival first implant | Months |

| Follow-up second implant | |

| Second implant reconstruction failure | Yes/no |

| Cause of second implant reconstruction failure | No failure |

| Survival second implant | Months |

BCSAR, breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy; NAC, nipple-areola complex; RRM, risk-reducing mastectomy.

| Personal data . | Level . |

|---|---|

| Age | Years |

| Smoker | Yes/no |

| BMI | Kg/m2 |

| Oncological data | |

| Location | Right/left |

| BCSAR | Yes/no |

| Tumor histology | |

| Tumor biology | |

| Oncological stage | |

| Cause of RRM | |

| RRM pattern | |

| NAC sparing | Yes/no |

| Reconstructive technique | Expander |

| Direct-to-implant | |

| Mixed techniques (flap + expander/implant) | |

| Follow-up first implant | |

| First implant reconstruction failure | Yes/no |

| Cause of first implant reconstruction failure | |

| Survival first implant | Months |

| Follow-up second implant | |

| Second implant reconstruction failure | Yes/no |

| Cause of second implant reconstruction failure | No failure |

| Survival second implant | Months |

| Personal data . | Level . |

|---|---|

| Age | Years |

| Smoker | Yes/no |

| BMI | Kg/m2 |

| Oncological data | |

| Location | Right/left |

| BCSAR | Yes/no |

| Tumor histology | |

| Tumor biology | |

| Oncological stage | |

| Cause of RRM | |

| RRM pattern | |

| NAC sparing | Yes/no |

| Reconstructive technique | Expander |

| Direct-to-implant | |

| Mixed techniques (flap + expander/implant) | |

| Follow-up first implant | |

| First implant reconstruction failure | Yes/no |

| Cause of first implant reconstruction failure | |

| Survival first implant | Months |

| Follow-up second implant | |

| Second implant reconstruction failure | Yes/no |

| Cause of second implant reconstruction failure | No failure |

| Survival second implant | Months |

BCSAR, breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy; NAC, nipple-areola complex; RRM, risk-reducing mastectomy.

RESULTS

A total of 101 RRMs with immediate SSBI reconstruction carried out on 64 patients (0% men; 100% women) were included in the study (Figure 1). The average age of the patients included in the study was 47.65 years (range, 26-72 years). In 15.8% (16) of cases there was a previous history of BCSAR due to primary breast cancer. The BCSAR group and the control group were comparable: no statistically significant differences were found in average age, laterality, BMI, smoking, RRM surgical pattern, nipple-areola complex preservation, or type of SSBI used in the breast reconstruction. As expected, statistically significant differences were only found in the indication of hybrid reconstructive techniques (flap supplemented with implant), which were used in only 1 patient in the control group (Table 2).

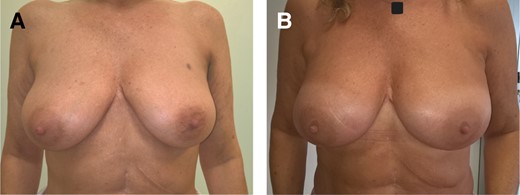

(A) Preoperative view of a 55-year-old female, with BRCA-2 mutation without previous breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy. (B) Postoperative view 16 months after risk-reducing mastectomy (inframammary incision) and immediate direct-to-implant reconstruction with Mentor CPG 323 440-cc implants (Mentor Worldwide, LLC, Irvine, CA). No complications, including capsular contracture, are observed.

| Characteristic . | Global . | BCSAR group . | No BCSAR group . | P valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.50 [10.87] years | 46.62 [12.12] | 41.73 [10.53] | P = .20 |

| Location | Right, 52; left, 49 | Right, 8; left, 8 | Right, 44; left, 41 | P = .90 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.01 [4.59] | 25.58 [4.54] | 26.09 [4.63] | P = .77 |

| Smoker | 16.80% (17) | 33.34% (4) | 18.60% (13) | P = .34 |

| Skin-sparing mastectomy surgical pattern Type I | 5.90% (6) | 6.25% (1) | 5.88% (5) | P = .95 |

| Skin-sparing mastectomy surgical pattern Type IV | 53.50 (54) | 62.5% (16) | 51.76% (44) | P = .43 |

| Skin-sparing mastectomy surgical pattern Type V | 19.80% (20) | 12.50% (2) | 4.70% (2) | P = .23 |

| Inframammary fold | 14.90% (15) | 21.43% (15) | 0.00% (0) | P = .07 |

| NAC-sparing | 45.50% (46)b | 43.75% (7) | 45.88 (39) | P = .87 |

| Type of implant | Becker: 96%c (97); direct-to-implant: 4% (4) | Becker: 93.75% (15);c direct-to-implant: 6.25% (1) | Becker: 96.47% (82);c direct-to-implant:3.53% (3) | P = .61 |

| Hybrid techniquesd | 7.9% (8) | 87.5% (7) | 1.18% (1) | P = .00 |

| Characteristic . | Global . | BCSAR group . | No BCSAR group . | P valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.50 [10.87] years | 46.62 [12.12] | 41.73 [10.53] | P = .20 |

| Location | Right, 52; left, 49 | Right, 8; left, 8 | Right, 44; left, 41 | P = .90 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.01 [4.59] | 25.58 [4.54] | 26.09 [4.63] | P = .77 |

| Smoker | 16.80% (17) | 33.34% (4) | 18.60% (13) | P = .34 |

| Skin-sparing mastectomy surgical pattern Type I | 5.90% (6) | 6.25% (1) | 5.88% (5) | P = .95 |

| Skin-sparing mastectomy surgical pattern Type IV | 53.50 (54) | 62.5% (16) | 51.76% (44) | P = .43 |

| Skin-sparing mastectomy surgical pattern Type V | 19.80% (20) | 12.50% (2) | 4.70% (2) | P = .23 |

| Inframammary fold | 14.90% (15) | 21.43% (15) | 0.00% (0) | P = .07 |

| NAC-sparing | 45.50% (46)b | 43.75% (7) | 45.88 (39) | P = .87 |

| Type of implant | Becker: 96%c (97); direct-to-implant: 4% (4) | Becker: 93.75% (15);c direct-to-implant: 6.25% (1) | Becker: 96.47% (82);c direct-to-implant:3.53% (3) | P = .61 |

| Hybrid techniquesd | 7.9% (8) | 87.5% (7) | 1.18% (1) | P = .00 |

Values are % and [total number of patients]. BCSAR, breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy; NAC, nipple-areola complex; SSBI, silicone shell breast implant. aStatistical significance if P ≤ .05. bThirty-three cases as a pedicled flap and 13 cases as a skin graft. cBecker 35 textured surface. dAll cases of muscular or myocutaneous latissimus dorsi flap supplemented with SSBI.

| Characteristic . | Global . | BCSAR group . | No BCSAR group . | P valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.50 [10.87] years | 46.62 [12.12] | 41.73 [10.53] | P = .20 |

| Location | Right, 52; left, 49 | Right, 8; left, 8 | Right, 44; left, 41 | P = .90 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.01 [4.59] | 25.58 [4.54] | 26.09 [4.63] | P = .77 |

| Smoker | 16.80% (17) | 33.34% (4) | 18.60% (13) | P = .34 |

| Skin-sparing mastectomy surgical pattern Type I | 5.90% (6) | 6.25% (1) | 5.88% (5) | P = .95 |

| Skin-sparing mastectomy surgical pattern Type IV | 53.50 (54) | 62.5% (16) | 51.76% (44) | P = .43 |

| Skin-sparing mastectomy surgical pattern Type V | 19.80% (20) | 12.50% (2) | 4.70% (2) | P = .23 |

| Inframammary fold | 14.90% (15) | 21.43% (15) | 0.00% (0) | P = .07 |

| NAC-sparing | 45.50% (46)b | 43.75% (7) | 45.88 (39) | P = .87 |

| Type of implant | Becker: 96%c (97); direct-to-implant: 4% (4) | Becker: 93.75% (15);c direct-to-implant: 6.25% (1) | Becker: 96.47% (82);c direct-to-implant:3.53% (3) | P = .61 |

| Hybrid techniquesd | 7.9% (8) | 87.5% (7) | 1.18% (1) | P = .00 |

| Characteristic . | Global . | BCSAR group . | No BCSAR group . | P valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.50 [10.87] years | 46.62 [12.12] | 41.73 [10.53] | P = .20 |

| Location | Right, 52; left, 49 | Right, 8; left, 8 | Right, 44; left, 41 | P = .90 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.01 [4.59] | 25.58 [4.54] | 26.09 [4.63] | P = .77 |

| Smoker | 16.80% (17) | 33.34% (4) | 18.60% (13) | P = .34 |

| Skin-sparing mastectomy surgical pattern Type I | 5.90% (6) | 6.25% (1) | 5.88% (5) | P = .95 |

| Skin-sparing mastectomy surgical pattern Type IV | 53.50 (54) | 62.5% (16) | 51.76% (44) | P = .43 |

| Skin-sparing mastectomy surgical pattern Type V | 19.80% (20) | 12.50% (2) | 4.70% (2) | P = .23 |

| Inframammary fold | 14.90% (15) | 21.43% (15) | 0.00% (0) | P = .07 |

| NAC-sparing | 45.50% (46)b | 43.75% (7) | 45.88 (39) | P = .87 |

| Type of implant | Becker: 96%c (97); direct-to-implant: 4% (4) | Becker: 93.75% (15);c direct-to-implant: 6.25% (1) | Becker: 96.47% (82);c direct-to-implant:3.53% (3) | P = .61 |

| Hybrid techniquesd | 7.9% (8) | 87.5% (7) | 1.18% (1) | P = .00 |

Values are % and [total number of patients]. BCSAR, breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy; NAC, nipple-areola complex; SSBI, silicone shell breast implant. aStatistical significance if P ≤ .05. bThirty-three cases as a pedicled flap and 13 cases as a skin graft. cBecker 35 textured surface. dAll cases of muscular or myocutaneous latissimus dorsi flap supplemented with SSBI.

The mean [standard deviation] time between the completion of radiotherapy treatment and RRM was 3.86 [1.21] years. In all the cases, Grade I chronic radiodermatitis was observed, with mild atrophy, mild fibrosis, mild hyperpigmentation, or mild subcutaneous fat loss.

In most cases, RRM was performed following the diagnosis of a genetic mutation with a high risk of developing breast cancer. In 49.5% (50) of the cases, there was a BRCA-1 mutation; in 16.8% (17) a BRCA-2 mutation; in 4% (4) an ATM mutation; in 3% (3) a simultaneous BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 mutation; and in 2% (2) a PALB2 mutation. In 9.9% (10) of the cases there was a proven familial risk of breast cancer with no specific mutation being diagnosed in the gene panel test. In 9.9% (10) of the cases, the indication for RRM was “cancerophobia,” always after an oncological process in the contralateral breast. In 5% (5) of cases, the indication was due to severe fibrocystic mastopathy.

Of the 16 cases with a history of breast cancer and subsequent BCSAR treatment, 7 had a Grade 3 invasive ductal carcinoma, eight had a Grade 2 invasive ductal carcinoma, and only 1 had a Grade 1invasive ductal carcinoma. The tumor was triple-negative in 5 cases, luminal B HER2-positive in 4 cases, luminal B HER2-negative in 4 cases, and luminal A in 3 cases. One case was classified as Stage IIIA, 2 as Stage IIB, 8 as Stage IIA, and 1 patient with a final anatomopathological diagnosis of in situ carcinoma was classified as Stage 0.

The first SSBI used in immediate reconstruction after RRM had to be replaced in 51.5% (52) of cases (Table 3). This includes early and late complications and other scenarios that cannot be classified precisely as complications, such as an unacceptable aesthetic result for the patient or severe breast asymmetry. The mean survival of this failed SSBI was 24.04 [28.48] months (range, 1-156 months). It was observed that a history of BCSAR was significantly associated with the development of capsular contracture (P = .00) in this first SSBI. In the group of patients with a history of BCSAR, the development of Grade III/IV capsular contracture was observed in 37.5% of cases (Figure 2), whereas in the control group it was observed in only 5.9% of cases. The mean survival of the first SSBI was 23.11 [24.00] months in the BCSAR group and 28.50 [45.33] months in the control group. However, no statistically significant differences were found when these means were compared (P = .12). The indication of hybrid reconstructive techniques in our series does not show statistically significant differences in the rate of capsular contracture (P = .88). The mean survival of failed SSBI due to capsular contracture was higher in the hybrid reconstructive techniques group (48 [59.97] months) than in the SSBI-only reconstruction group (21.76 [23.21] months), although statistically significant values (P = .33) were not obtained. In fact, multiple-regression analysis showed that the use of hybrid reconstructive techniques did not significantly increase implant survival in patients with previous BCSAR (P = .11).

A 32-year-old female patient diagnosed with BRCA-1 mutation who underwent breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy in the left breast due to ductal carcinoma in the upper outer quadrant (areolar incision) is shown 9 months after the end of radiotherapy. Lateral extension of the previous areolar incision was employed as an approach to the left risk-reducing mastectomy. Right breast risk-reducing mastectomy was performed by the inframammary approach. Immediate reconstruction with 400-cc Becker 35 implants were realized with an initial volume of 300 cc. The final volume of 400 cc was achieved 1 month later. Fourteen months after the procedure she presented with a Grade IV capsular contracture with severe retraction in the nipple-areola complex area of the left irradiated breast.

| Cause . | N . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Capsular contracture | 11 | 10.9% |

| Extrusion | 6 | 5.9% |

| Rotation | 5 | 5% |

| Infection | 12 | 11.9% |

| Implant rupture | 2 | 2% |

| Unsatisfactory result | 11 | 10.9% |

| Discomfort without contracture | 4 | 4% |

| Unclarified causes | 1 | 1% |

| Cause . | N . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Capsular contracture | 11 | 10.9% |

| Extrusion | 6 | 5.9% |

| Rotation | 5 | 5% |

| Infection | 12 | 11.9% |

| Implant rupture | 2 | 2% |

| Unsatisfactory result | 11 | 10.9% |

| Discomfort without contracture | 4 | 4% |

| Unclarified causes | 1 | 1% |

| Cause . | N . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Capsular contracture | 11 | 10.9% |

| Extrusion | 6 | 5.9% |

| Rotation | 5 | 5% |

| Infection | 12 | 11.9% |

| Implant rupture | 2 | 2% |

| Unsatisfactory result | 11 | 10.9% |

| Discomfort without contracture | 4 | 4% |

| Unclarified causes | 1 | 1% |

| Cause . | N . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Capsular contracture | 11 | 10.9% |

| Extrusion | 6 | 5.9% |

| Rotation | 5 | 5% |

| Infection | 12 | 11.9% |

| Implant rupture | 2 | 2% |

| Unsatisfactory result | 11 | 10.9% |

| Discomfort without contracture | 4 | 4% |

| Unclarified causes | 1 | 1% |

As far as early complications following RRM are concerned, such as implant infection, mastectomy flap necrosis, or surgical wound dehiscence with implant extrusion (Figures 3, 4), no statistically significant differences were found between the BCSAR group and the control group (P = .68). Neither were there any statistically significant differences in the incidence of early complications when hybrid reconstructive techniques or direct-to-implant reconstructions were used (P = .47). Some early complications after RRM and SSBI reconstruction arose in 22.8% (23) of the cases. In the BCSAR group, 18.8% (3) of cases had an early complication that led to implant removal and subsequent reconstruction failure, while in the control group this situation occurred in 23.5% (20) of cases. The most common early complication associated with reconstruction failure in both groups was implant infection (2 cases in the BCSAR group; 12 cases in the control group), followed by mastectomy flap necrosis (1 case in the BCSAR group; 6 cases in the control group), and surgical wound dehiscence with implant extrusion (0 cases in the BCSAR group; 2 cases in the control group).

A 47-year-old female patient with previous breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy in her left breast who 18 days after risk-reducing mastectomy and direct-to-implant reconstruction presented full cutaneous necrosis in the nipple-areola complex and vertical incision. The necrotic area was debrided, and the implant was replaced by a Becker 35 expander (Mentor Worldwide, LLC Irvine, CA).

A 51-year-old female patient presenting massive necrosis in the lower nipple-areola complex and the lower outer quadrant of the breast. Although this patient had not not undergone breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy in this breast, she was a heavy smoker. Debridement and temporary removal of the implant was performed.

Of the cases requiring the replacement of the first SSBI, 44.23% (23) suffered the subsequent failure of the second SSBI (Table 4) with a mean survival of 27.95 [26.53] months (range, 1-91 months). Early implant failure occurred in only 13% (3) of cases, all due to infection. No association was found between the occurrence of early reconstruction failure and history of previous BCSAR (P = .43). Grade III/IV capsular contracture occurred in 26.1% (6) of cases of second SSBI failure, with only 2 cases belonging to the BCSAR group. Once again, no statistically significant association was found between the consecutive development of capsular contracture in the second SSBI used and previous history of BCSAR (P = .10), although the size of the studied subgroup was very small. The mean survival of the second SSBI in cases with capsular contracture was 38.67 [24.45] months (range, 11-70 months).

| Cause . | N . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| No failure | 29 | 28.7% |

| Capsular contracture | 6 | 5.9% |

| Rotation | 3 | 3% |

| Infection | 3 | 3% |

| Implant rupture | 2 | 2% |

| Unsatisfactory result | 8 | 7.9% |

| Discomfort without contracture | 1 | 1% |

| Unclarified cause | 2 | 2% |

| No second implant | 47 | 46.5% |

| Cause . | N . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| No failure | 29 | 28.7% |

| Capsular contracture | 6 | 5.9% |

| Rotation | 3 | 3% |

| Infection | 3 | 3% |

| Implant rupture | 2 | 2% |

| Unsatisfactory result | 8 | 7.9% |

| Discomfort without contracture | 1 | 1% |

| Unclarified cause | 2 | 2% |

| No second implant | 47 | 46.5% |

| Cause . | N . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| No failure | 29 | 28.7% |

| Capsular contracture | 6 | 5.9% |

| Rotation | 3 | 3% |

| Infection | 3 | 3% |

| Implant rupture | 2 | 2% |

| Unsatisfactory result | 8 | 7.9% |

| Discomfort without contracture | 1 | 1% |

| Unclarified cause | 2 | 2% |

| No second implant | 47 | 46.5% |

| Cause . | N . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| No failure | 29 | 28.7% |

| Capsular contracture | 6 | 5.9% |

| Rotation | 3 | 3% |

| Infection | 3 | 3% |

| Implant rupture | 2 | 2% |

| Unsatisfactory result | 8 | 7.9% |

| Discomfort without contracture | 1 | 1% |

| Unclarified cause | 2 | 2% |

| No second implant | 47 | 46.5% |

Of all the cases included in the study, 48.5% (49) had no complications up to the cut-off date, with a mean follow-up of 48.98 [36.75] months (range, 12-178 months). A total of 12.76% (6) of these had a previous history of BCSAR, with a mean follow-up of 56.67 [25.81] months for this group.

DISCUSSION

Very little specific information has been published in the literature regarding the long-term survival of breast implants used for reconstruction after mastectomy.20 Most of the studies show limited follow-up periods or, surprisingly, avoid late complications associated with implants such as capsular contracture. The exclusive focus on implant behavior in patients who have previously undergone BCSAR and subsequent RRM with immediate implant reconstruction has not specifically been the subject of analysis. Most of the published series focus on primary breast reconstruction with implants in patients who have undergone mastectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy. Complications reported in these series vary according to the reconstructive sequence employed but can reach reconstructive failure rates of nearly 50%.21 Pathological capsular contracture, included or not as a cause of reconstructive failure, can reach values up to 57.8% with a mean follow-up of 50 months.22 Khansa et al, in a prospective study, revealed that 40.0% of patients who underwent breast reconstruction after mastectomy with previous BCSAR developed a complication of some sort in a mean follow-up of 23.3 months.18 Unfortunately, only 7% (10) of cases in that study were reconstructed with implants and only 2% (3) of cases were RRMs, and so it cannot be compared directly to our study. It is well known that these series have described an increase in the rate of certain complications such as infection, tissue necrosis, implant extrusion, and wound dehiscence, and, in particular, an increased incidence of capsular contracture, the most frequent complication in irradiated implant-based breast reconstruction. In a prospective cohort study, Krueger et al concluded that patients who received radiotherapy before or after an implant-based reconstruction had a statistically significant higher rate of complications and reconstruction failure.23 However, they found no statistically significant differences in aesthetic and overall satisfaction despite higher rates of complications and reconstruction failure in patients receiving radiotherapy. Cordeiro et al studied the behavior of SSBIs in a group of patients who underwent mastectomy and immediate reconstruction with an expander followed by chemotherapy during the tissue expansion period.24 Four weeks after the end of chemotherapy, the expander was replaced with a definitive implant. Four weeks after the replacement, the patients received radiotherapy if indicated. The rate of capsular contracture in irradiated patients was significantly higher than in nonirradiated patients (68% vs 48%). Subsequently, several studies have continued to report significantly higher failure rates for implant breast reconstruction in patients who received radiotherapy, regardless of whether the radiotherapy was given before or after the final implant was inserted.25,26

Implant localization, ie, prepectoral or retropectoral, is a topic currently under discussion,27,28 including in RRM,29,30 especially when using polyurethane shell implants or ADM. In our experience, prepectoral locations of the implant are shorter than retropectoral in irradiated RRMs so this group of patients was not included in the study to avoid a potential source of bias.

Most of the implants employed were Becker type (Table 2). The use of a Becker implant or a conventional silicone implant in breast reconstruction will depend on the surgeon's preference, the quality of the mastectomy flap, and the patient's characteristics.31 In the context of skin-sparing or nipple-sparing mastectomy, we prefer to employ direct-to-implant reconstruction when there is a severe nonptotic or hypertrophic breast, in a nonobese, nonheavy smoker, and when the patient has not previously been irradiated. Any sign of cutaneous suffering in the mastectomy flaps or a patient with a high risk of cutaneous necrosis will lead us to employ a Becker implant to avoid excessive tension in the first days after surgery.

Hybrid breast reconstruction techniques or techniques that use autologous tissue supplemented by an implant would, a priori, seem to be an appropriate solution to reduce the rate of complications in patients who have undergone radiotherapy and reconstruction with implants. However, the relative lack of follow-up literature published on the subject does not allow us to be optimistic that hybrid techniques offer a significant improvement in capsular contracture rates.32,33 In our series, hybrid breast reconstruction techniques have been used anecdotally, thus making it impossible to draw any statistical conclusions.

Based on previous published literature, we do not use ADM in the case of previous radiotherapy. The iBAG study, which analyzed 1450 RRM procedures that used Braxon ADM, concluded that radiation therapy appeared to be a statistically significant risk factor for the development of postoperative seroma, capsular contracture, rippling, and implant loss.34 However, other previous studies point out that the use of ADM for implant-based breast reconstruction in irradiated patients does not appear to increase or decrease the risk of complications.35

It is well known that autologous breast reconstruction after mastectomy, with radiation therapy before or after reconstruction, has a lower rate of major complications, especially reconstruction failure, when compared with implant-based breast reconstruction. Berry et al found that overall and minor complication rates were similar between autologous breast reconstruction and expander/implant-based reconstruction in irradiated patients.36 However, when major complications were analyzed, they observed statistically significant higher rates in the implant-based reconstructed group (P = .049). In a recent study, Reinders et al compared implant-based breast reconstruction with autologous breast reconstruction in patients who had received radiotherapy after mastectomy.37 A significant rate of complications was observed in the group of patients who underwent implant-based breast reconstruction. However, these authors’ most striking finding was that radiotherapy was associated with a 21% rate of reconstruction failure in the implant-based reconstruction group with no failures being observed in the autologous tissue reconstruction group. Patient satisfaction was statistically significantly lower in the group who underwent implant-based reconstruction compared with the group reconstructed with autologous tissues (50.9% vs 63.7%; P = .01).

Although autologous reconstruction techniques are a safe option for patients with a previous history of radiotherapy, they imply a more technically demanding and skill-dependent surgical procedure associated with longer operating times and hospital stays. For these reasons, in addition to the presence of certain complications, comorbidities, or simply patient preference, not all patients are suitable for autologous reconstruction, especially when the reconstruction is bilateral, as usually occurs in the case of RRM. In this scenario, polyurethane-coated implants may provide a good alternative to purely autologous reconstruction. Polyurethane-coated implants seem to have a significantly reduced rate of capsular contracture, particularly among irradiated patients.38-40 In a study conducted by Castel et al on breast augmentation with polyurethane-coated implants in 382 patients, Grade III/IV capsular contracture was observed in only 2.1% of the cases. In their study, Pompei et al included breast reconstruction patients with and without previous radiation therapy.40 The overall Grade III/IV capsular contracture rate at 9 years was 8.1% for patients reconstructed with polyurethane-coated implants, 10.7% in patients with previous radiotherapy, and 5.5% in patients without radiation. The behavior of polyurethane-coated breast implants in the specific situation of RRM with previous BCSAR has never been analyzed and our experience with these implants in this specific context is short, so we decided to exclude patients with polyurethane-coated implants to avoid a potential source of bias. There is no doubt that a well-planned study with a comparable polyurethane-coated implant group would be of great interest to study the evolution of this group of patients.

A potential limitation of this study could be the number of patients in the group of patients with previous BCSAR. In our current clinical practice, a considerable number of patients choose an autologous reconstruction if previous radiation therapy had been applied, after mastectomy or after BCS. We usually offer both types of reconstruction but always take into account the characteristics of the patient and her preferences after careful explanation of the limitations and potential complications with any technique. Many of our patients choose the autologous option because they prefer a stable and long-lasting result.

CONCLUSIONS

A history of BCSAR prior to RRM immediately reconstructed with an SSBI is associated with a significant increase in Baker Grade III/IV capsular contracture. The use of hybrid techniques (flap supplemented by an SSBI) is not associated with an increase in the survival of the SSBI in patients with previous BCSAR, although this is a subgroup analysis with a small sample size. In these cases, patients should be warned of the significant increase in the rate of SSBI complications and reconstruction failures. Polyurethane-coated implants may be a reasonable alternative in cases in which alloplastic reconstruction is considered in patients with previous BCSAR.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Drs Couto-González, Fernández-Marcos, Brea-García, Canseco-Díaz, and Mato-Codesido are consultants, University Hospital of Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain.

Dr García-Arjona is a resident, and Dr Taboada-Suárez is head of department, Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, University Hospital of Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain.

Dr González-Giménez is a postgraduate medical student, University Hospital of Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain.