-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Francisco R Avila, Daniel Boczar, Aaron C Spaulding, Daniel J Quest, Arindam Samanta, Ricardo A Torres-Guzman, Karla C Maita, John P Garcia, Abdullah S Eldaly, Antonio J Forte, High Satisfaction With a Virtual Assistant for Plastic Surgery Frequently Asked Questions, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 43, Issue 4, April 2023, Pages 494–503, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjac290

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Most of a surgeon's office time is dedicated to patient education, preventing an appropriate patient-physician relationship. Telephone-accessed artificial intelligent virtual assistants (AIVAs) that simulate a human conversation and answer preoperative frequently asked questions (FAQs) can be effective solutions to this matter. An AIVA capable of answering preoperative plastic surgery–related FAQs has previously been described by the authors.

The aim of this paper was to determine patients’ perception and satisfaction with an AIVA.

Twenty-six adult patients from a plastic surgery service answered a 3-part survey consisting of: (1) an evaluation of the answers’ correctness, (2) their agreement with the feasibility, usefulness, and future uses of the AIVA, and (3) a section on comments. The first part made it possible to measure the system's accuracy, and the second to evaluate perception and satisfaction. The data were analyzed with Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA).

The AIVA correctly answered the patients’ questions 98.5% of the time, and the topic with the lowest accuracy was “nausea.” Additionally, 88% of patients agreed with the statements of the second part of the survey. Thus, the patients’ perception was positive and overall satisfaction with the AIVA was high. Patients agreed the least with using the AIVA to select their surgical procedure. The comments provided improvement areas for subsequent stages of the project.

The results show that patients were satisfied and expressed a positive experience with using the AIVA to answer plastic surgery FAQs before surgery. The system is also highly accurate.

See the Commentary on this article here.

The time spent in patient education, which involves providing them with information, instructions, and counseling, can vary from 19% to 48% of the dedicated office time per patient.1 In addition, a recent survey showed that surgical patients are interested in receiving information on what to expect in the preoperative period, during anesthesia, and in the postoperative period, as well as general hospital information.2 However, the authors also found that the attending surgeons thought patients were more interested in being educated on the evolution of their disease.2 Thus, the time spent conveying more information than a patient needs might prevent the surgeon from establishing a solid patient-physician relationship during the already short allocated preoperative consultation time. Having this information available for patients at any time might help overcome this hindrance.

Interactive voice response systems are computer-automated telephone technologies that patients can use to communicate via their telephone keypad or voice that aim to simulate a conversation with a human. In healthcare, this technology has been used for depression screening,3 caring for patients with chronic diseases such as hypertension4,5 and diabetes,6 following up patients with chronic pain,7 follow-ups after outpatient visits,8,9 promoting smoking cessation,10 evaluating postoperative patient status,11 improving medication compliance,12-14 enhancing medication intoxication screening,15,16 and applying satisfaction surveys.17 This technology is usually limited in its ability to understand what the patient communicates. With the advent of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and natural language processing, technological advances have allowed the evolution of these systems to artificial intelligent virtual assistants (AIVAs), capable of engaging in a more structured conversation.

These new technologies have allowed computerized systems to recognize how an idea can be written or verbalized and respond accordingly. Some of these AIVAs can recognize emotion in a patient's voice and infuse their answer with a corresponding emotion to help patients cope with frustration.18,19 These AIVAs have also been used to collect information on the health status of patients with Parkinson's disease while measuring voice and communication outcomes.20,21 Similar to this, these conversational agents have also been used as screening tools to detect mild cognitive impairment and evaluate the risk of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer.22,23 Another surgical field in which AIVAs will soon be used is ophthalmology, with conversational agents detecting cataract surgery complications.24 Lastly, these AIVAs have also been tested during the current COVID-19 pandemic by providing patient follow-up and redirecting them to human evaluation if needed.25

Implementing an AIVA to answer preoperative frequently asked questions (FAQs) could increase the time dedicated to building a strong patient-physician relationship, leading to increased patient satisfaction and improved surgical outcomes. In a previous report, we provided evidence of the accuracy of our AIVA in answering some of the most frequently asked questions by patients before surgery. By surveying subjects in administrative positions at our institution, we found that our AIVA provided the correct answer to their questions on prespecified topics on more than 90% of occasions. Additionally, the subjects considered these answers correct in 83% of cases.26 An AIVA that answers patients’ specific questions is also in line with needs-based patient education. This method consists of individually tailoring the information patients receive based on what they want to know. This method decreases anxiety and education time and increases patient satisfaction.27 Ultimately, if a patient needs a more detailed answer than the one provided by an AIVA, the preoperative consult can focus on specific topics of interest. This way, time would be used effectively, and additional information that might not be of benefit or that could increase anxiety would be omitted.28

As a first step towards establishing this system as the standard of care in our service, we hypothesize that preoperative patients undergoing plastic surgery procedures will be satisfied with the AIVA. Therefore, we aimed to determine the patients’ perception of the AIVA by measuring their agreement with perceptions of usefulness through a Likert scale-type survey.

METHODS

Training of the Artificial Intelligent Virtual Assistant

The initial training process of the AIVA was explained in a previous study.26 After that, we transferred the AIVA to Google Dialogflow (Google; Mountain View, CA). The AIVA's development in this platform was as follows. The first step in creating a chatbot in the Google Dialogflow platform is creating a “Project.” Each project can contain multiple “Agents.” In this project, we created an agent named “AIVA,” capable of answering questions of 10 different preselected topics on plastic surgery. Each of these topics has a standard answer. The topics and answers are described in our previous study.26 Because it is possible to ask about the same topic in many different ways, we framed the possible questions associated with each particular topic. After creating the Project and its associated Agent, we channeled each topic through a different path. This was required to avoid overlapping of the topics. In Google Dialogflow, each channel is called “Route.” We created 1 channel per topic, hence we created 10 Routes. Each Route is capable of handling multiple “Intents.” This means that multiple questions could be asked for the same topic. In our case, each topic has a single Intent whose sentence structure (ie, question) was framed in multiple ways.

Structurally, 1 Route has 4 components (ie, Intent, Condition, Fulfillment, and Transition). Inside the Intent component, the “Training Phrases” help train the Dialogflow natural language processing model by providing syntactically different questions, ultimately looking for the same answer. The Condition component checks all criteria before moving to the next step. Here, because our AIVA only gives answers, the Condition component checks if the user's question matches the particular Intent. After criteria matching, the Fulfillment component transfers the control from Route to “next page” through the Transition component. The next page, associated with each Route, contains the standard answer of the Intent. The AIVA then provides the answer from the page by reading or writing it, depending on the communication medium.

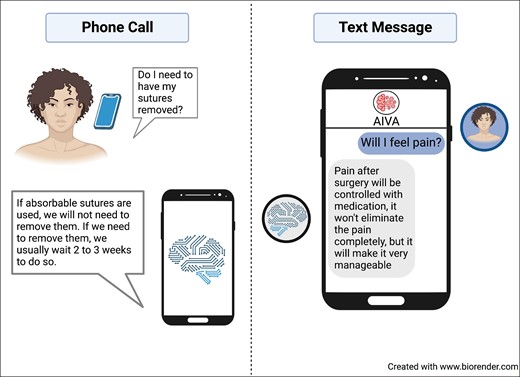

The final step in the creation of the AIVA is to connect it with the media providing the interface. There are two types of media available: “One-click Telephony” and “Text Based” in the Dialogflow CX version. The first type allows subjects to call the AIVA from a landline or mobile phone. We used the “Phone Getaway” service provided by Dialogflow to enable the “Calling the Bot” feature. Currently, Dialogflow has terminated the “Phone Gateway” service, but there are services available by third parties. Importantly, the chatbot can be further modified. Lastly, it is important to note that patients do not pay for this technology, as its costs are entirely associated with its development and maintenance (consult https://cloud.google.com/dialogflow/pricing for more information). Figure 1 shows a representation of how the AIVA operates.

Interaction between patients and the AIVA. On the left, the patients call a phone number linked to the chatbot. The patients can ask their questions in any way, and the AIVA will provide the correct standardized answer as the attending surgeon would do. On the right, the patients also have the option of texting the number using their mobile phones. If they choose to use this approach, they will receive a text message with the appropriate answer to their question. AIVA, artificial intelligent virtual assistant.

Survey

We received approval to perform this study by our institution's IRB under protocol number 19-003768. This study includes plastic surgery patients aged over 18 years from our institution's Division of Plastic Surgery outpatient clinic. Twenty-six patients were recruited randomly and surveyed between December 30, 2020, and February 4, 2021 (1 month and 5 days). Written consent was provided, by which patients agreed to the use and analysis of their data. Participants were informed that the answers would be kept in a deidentified, confidential manner.

First, the participating patients called an office number linked to the AIVA from a phone provided by the study personnel in one of the examination rooms of the plastic surgery service. Next, the study personnel put the phone on speaker for patients to ask the scripted questions of the first part of the survey, after which they would evaluate the correctness of the answers by determining if the answers were correct, correct but incomplete, or incorrect. We expect the AIVA to reach the same accuracy as our previous pilot study with administrative employees. After the call, patients were asked to complete the second and third parts of the survey to evaluate their perception of the AIVA by grading their agreement level with the statements shown in Table 1 on a 5-point Likert scale and providing their comments. Optimal patient satisfaction will be achieved if at least 75% of patients answer “completely agree” or “agree” to the specified statements and overall.

List of Statements on the Use of the Plastic Surgery AIVA for Which Patient Agreement Was Evaluated

| 1. This virtual assistant meets my approval. |

| 2. This virtual assistant is appealing to me. |

| 3. I like this virtual assistant. |

| 4. I welcome this virtual assistant. |

| 5. This virtual assistant seems fitting. |

| 6. This virtual assistant seems suitable. |

| 7. This virtual assistant seems applicable. |

| 8. This virtual assistant seems like a good match. |

| 9. This virtual assistant seems implementable. |

| 10. This virtual assistant seems possible. |

| 11. This virtual assistant seems doable. |

| 12. This virtual assistant seems easy to use. |

| 13. This virtual assistant answered you properly. |

| 14. This virtual assistant could be helpful for patients. |

| 15. I would use a virtual assistant to answer my questions before surgery. |

| 16. I would use this virtual assistant to answer my questions after surgery. |

| 17. I would use the virtual assistant to schedule appointments at Mayo Clinic. |

| 18. I would use the virtual assistant to better understand my surgical procedure. |

| 19. I would use answers provided by a virtual assistant to help me choose my procedure (eg, type of technique). |

| 20. A virtual assistant could allow me to spend better time with my physician. |

| 21. A virtual assistant could allow me to have a better post-operative follow-up at home. |

| 1. This virtual assistant meets my approval. |

| 2. This virtual assistant is appealing to me. |

| 3. I like this virtual assistant. |

| 4. I welcome this virtual assistant. |

| 5. This virtual assistant seems fitting. |

| 6. This virtual assistant seems suitable. |

| 7. This virtual assistant seems applicable. |

| 8. This virtual assistant seems like a good match. |

| 9. This virtual assistant seems implementable. |

| 10. This virtual assistant seems possible. |

| 11. This virtual assistant seems doable. |

| 12. This virtual assistant seems easy to use. |

| 13. This virtual assistant answered you properly. |

| 14. This virtual assistant could be helpful for patients. |

| 15. I would use a virtual assistant to answer my questions before surgery. |

| 16. I would use this virtual assistant to answer my questions after surgery. |

| 17. I would use the virtual assistant to schedule appointments at Mayo Clinic. |

| 18. I would use the virtual assistant to better understand my surgical procedure. |

| 19. I would use answers provided by a virtual assistant to help me choose my procedure (eg, type of technique). |

| 20. A virtual assistant could allow me to spend better time with my physician. |

| 21. A virtual assistant could allow me to have a better post-operative follow-up at home. |

The 21 statements of this list were answered using a 5-point Likert scale with the following options: completely disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree and completely agree. AIVA, artificial intelligent virtual assistant.

List of Statements on the Use of the Plastic Surgery AIVA for Which Patient Agreement Was Evaluated

| 1. This virtual assistant meets my approval. |

| 2. This virtual assistant is appealing to me. |

| 3. I like this virtual assistant. |

| 4. I welcome this virtual assistant. |

| 5. This virtual assistant seems fitting. |

| 6. This virtual assistant seems suitable. |

| 7. This virtual assistant seems applicable. |

| 8. This virtual assistant seems like a good match. |

| 9. This virtual assistant seems implementable. |

| 10. This virtual assistant seems possible. |

| 11. This virtual assistant seems doable. |

| 12. This virtual assistant seems easy to use. |

| 13. This virtual assistant answered you properly. |

| 14. This virtual assistant could be helpful for patients. |

| 15. I would use a virtual assistant to answer my questions before surgery. |

| 16. I would use this virtual assistant to answer my questions after surgery. |

| 17. I would use the virtual assistant to schedule appointments at Mayo Clinic. |

| 18. I would use the virtual assistant to better understand my surgical procedure. |

| 19. I would use answers provided by a virtual assistant to help me choose my procedure (eg, type of technique). |

| 20. A virtual assistant could allow me to spend better time with my physician. |

| 21. A virtual assistant could allow me to have a better post-operative follow-up at home. |

| 1. This virtual assistant meets my approval. |

| 2. This virtual assistant is appealing to me. |

| 3. I like this virtual assistant. |

| 4. I welcome this virtual assistant. |

| 5. This virtual assistant seems fitting. |

| 6. This virtual assistant seems suitable. |

| 7. This virtual assistant seems applicable. |

| 8. This virtual assistant seems like a good match. |

| 9. This virtual assistant seems implementable. |

| 10. This virtual assistant seems possible. |

| 11. This virtual assistant seems doable. |

| 12. This virtual assistant seems easy to use. |

| 13. This virtual assistant answered you properly. |

| 14. This virtual assistant could be helpful for patients. |

| 15. I would use a virtual assistant to answer my questions before surgery. |

| 16. I would use this virtual assistant to answer my questions after surgery. |

| 17. I would use the virtual assistant to schedule appointments at Mayo Clinic. |

| 18. I would use the virtual assistant to better understand my surgical procedure. |

| 19. I would use answers provided by a virtual assistant to help me choose my procedure (eg, type of technique). |

| 20. A virtual assistant could allow me to spend better time with my physician. |

| 21. A virtual assistant could allow me to have a better post-operative follow-up at home. |

The 21 statements of this list were answered using a 5-point Likert scale with the following options: completely disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree and completely agree. AIVA, artificial intelligent virtual assistant.

The answers to the survey were collected and stored in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Vanderbilt University; Nashville, TN)29,30 hosted at Mayo Clinic, which is password-protected to prevent privacy breaches. These data were deidentified by means of a numerical ID. Therefore, every participant was assigned a number from 1 to 26. The patient's age and gender were also collected.

Data Analysis

The frequency of the survey answers was tabulated with Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, WA) for its presentation as charts. The degree of agreement associated with each question is identified through both frequency and percentages. The accuracy of the AIVA was also calculated by dividing the number of times the system provided a correct answer to the patients’ question over the total number of answers. The resulting value was then expressed as a percentage. The data supporting these findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) and Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) checklists were considered for the creation of this manuscript.

RESULTS

Participants

Twenty-six patients answered the satisfaction survey, but only 24 completed it fully. However, all patients were included in the analysis. Considering this, we did not perform a nonresponder analysis. One patient declined to complete the survey after answering 8 questions, stating that she would rather have her preoperative questions answered by a real person. Another patient skipped questions 6 and 7, stating that some of the questions were redundant. Their mean [standard deviation] age was 56.7 [9.82] years (range, 29-79 years), with the highest proportion of patients aged between 50 and 59 years (57.7%). Of these patients, 21 were females (80.8%), and 5 were males (19.2%).

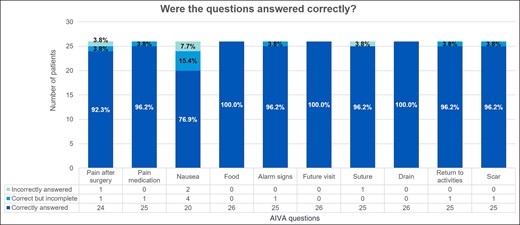

Accuracy

The patients considered that the AIVA answers were correct in 95% of cases, while they were correct but incomplete in 3.5% of cases and incorrect in only 1.5% of the cases. Therefore, the accuracy of the AIVA was 98.5%. The topic with the highest number of incorrect answers was “nausea,” with patients considering the provided information incorrect in 7.7% of cases. Additionally, “nausea” also had the highest number of correct but incomplete answers (15.4% of cases). On the other hand, the information on “food,” “future visits,” and “drains” was considered correct by patients in 100% of cases. The total number of patients and the percentage of patients per answer are presented in Figure 2.

Patient opinion on the correctness of answers given by the artificial intelligent virtual assistant to questions. AIVA, artificial intelligent virtual assistant.

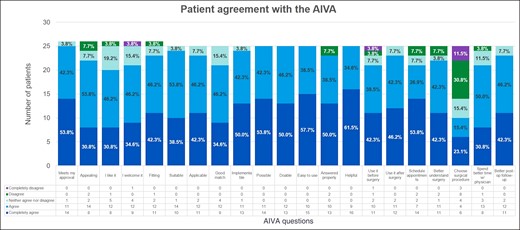

Patient Agreement With the AIVA

Regarding the second half of the survey, 88% of patients answered either “completely agree” or “agree,” while 7% answered “neither agree nor disagree,” and 5% answered either “disagree” or “completely disagree.” By adding the percentages of “completely agree” and “agree,” the questions with the highest agreement levels were about the general approval of the AIVA (96.1%), its feasibility (ie, if the AIVA is possible and doable, both with 100% agreement), helpfulness (100%), and ease of use (100%). Overall, all the statements exceeded the 75% agreement level, with the exception of that stating the AIVA could help patients choose their surgical procedure. More precisely, 11.5% of the participants stated they completely disagreed that the AIVA would be useful for this purpose, and 30.8% stated they disagreed. By combining these percentages, 42.3% of participants disagreed on this topic. Furthermore, 15.4% of patients remained neutral, and only 15.4% and 23.1% selected agree and completely agree, respectively. This translates to a total of 38.5% of patients agreeing on this subject. Therefore, most patients disagreed on the use of the AIVA to help them choose their surgical procedure. The total number of patients and the percentage of answers per statement are presented in Figure 3.

Patient agreement with the artificial intelligent virtual assistant on different areas. AIVA, artificial intelligent virtual assistant.

Patient Comments

The topics of the comments were grouped into 5 areas: “wrong answers,” “missing questions,” “additional information for the answers,” “problems with the virtual assistant,” and “other comments.” The most relevant comments on each of these areas are listed in Table 2. Overall, patients thought that the AIVA was a helpful system and provided suggestions that could improve it.

| Wrong answers |

| 1. The patient was told something different from a team member regarding suture removal. |

| 2. The patient received an answer to a different question. |

| 3. Answers to two of the questions were the same. |

| Missing questions |

| 1. The AIVA could benefit from a question about wearing a brace after surgery. |

| 2. The AIVA could benefit from a question regarding the use of a bra after surgery. |

| Additional information for the answers |

| 1. The answer for “nausea” could have tips for patients. |

| 2. Answers might be too fast for an old patient. |

| 3. Some questions could benefit from rephrasing. |

| 4. Some questions may benefit from more detailed answers. |

| Problems with the virtual assistant |

| 1. The AIVA hung up when the patient said “Thank you.” |

| 2. One patient did not understand how to ask a question. |

| Other comments |

| 1. The AIVA could be more helpful for patients undergoing a first or second surgery. |

| 2. The AIVA is better than an app or website. |

| 3. Some patients prefer to talk in person, stating that there is enough impersonality in medicine already. |

| 4. The AIVA is very useful. |

| Wrong answers |

| 1. The patient was told something different from a team member regarding suture removal. |

| 2. The patient received an answer to a different question. |

| 3. Answers to two of the questions were the same. |

| Missing questions |

| 1. The AIVA could benefit from a question about wearing a brace after surgery. |

| 2. The AIVA could benefit from a question regarding the use of a bra after surgery. |

| Additional information for the answers |

| 1. The answer for “nausea” could have tips for patients. |

| 2. Answers might be too fast for an old patient. |

| 3. Some questions could benefit from rephrasing. |

| 4. Some questions may benefit from more detailed answers. |

| Problems with the virtual assistant |

| 1. The AIVA hung up when the patient said “Thank you.” |

| 2. One patient did not understand how to ask a question. |

| Other comments |

| 1. The AIVA could be more helpful for patients undergoing a first or second surgery. |

| 2. The AIVA is better than an app or website. |

| 3. Some patients prefer to talk in person, stating that there is enough impersonality in medicine already. |

| 4. The AIVA is very useful. |

Patient comments were divided into 5 different areas, shown in this table. The most relevant comments on these areas are also shown. AIVA, artificial intelligent virtual assistant.

| Wrong answers |

| 1. The patient was told something different from a team member regarding suture removal. |

| 2. The patient received an answer to a different question. |

| 3. Answers to two of the questions were the same. |

| Missing questions |

| 1. The AIVA could benefit from a question about wearing a brace after surgery. |

| 2. The AIVA could benefit from a question regarding the use of a bra after surgery. |

| Additional information for the answers |

| 1. The answer for “nausea” could have tips for patients. |

| 2. Answers might be too fast for an old patient. |

| 3. Some questions could benefit from rephrasing. |

| 4. Some questions may benefit from more detailed answers. |

| Problems with the virtual assistant |

| 1. The AIVA hung up when the patient said “Thank you.” |

| 2. One patient did not understand how to ask a question. |

| Other comments |

| 1. The AIVA could be more helpful for patients undergoing a first or second surgery. |

| 2. The AIVA is better than an app or website. |

| 3. Some patients prefer to talk in person, stating that there is enough impersonality in medicine already. |

| 4. The AIVA is very useful. |

| Wrong answers |

| 1. The patient was told something different from a team member regarding suture removal. |

| 2. The patient received an answer to a different question. |

| 3. Answers to two of the questions were the same. |

| Missing questions |

| 1. The AIVA could benefit from a question about wearing a brace after surgery. |

| 2. The AIVA could benefit from a question regarding the use of a bra after surgery. |

| Additional information for the answers |

| 1. The answer for “nausea” could have tips for patients. |

| 2. Answers might be too fast for an old patient. |

| 3. Some questions could benefit from rephrasing. |

| 4. Some questions may benefit from more detailed answers. |

| Problems with the virtual assistant |

| 1. The AIVA hung up when the patient said “Thank you.” |

| 2. One patient did not understand how to ask a question. |

| Other comments |

| 1. The AIVA could be more helpful for patients undergoing a first or second surgery. |

| 2. The AIVA is better than an app or website. |

| 3. Some patients prefer to talk in person, stating that there is enough impersonality in medicine already. |

| 4. The AIVA is very useful. |

Patient comments were divided into 5 different areas, shown in this table. The most relevant comments on these areas are also shown. AIVA, artificial intelligent virtual assistant.

DISCUSSION

Patient experience, and therefore satisfaction, is now a crucial metric in the US healthcare system since the introduction of the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.31 It is part of a set of quality measures that can substantially impact hospital revenue if poorly scored. On the other hand, the association of patient satisfaction with objective surgical quality measures is still debated. Although some studies report the lack of an association between these 2 variables,32,33 others have found that hospitals with high satisfaction scores have a lower risk of death, failure to rescue, and minor complications.34,35 Despite these contrasting findings on the benefit of high satisfaction scores, patient experience ultimately reflects the state of the physician-patient relationship and the patients’ well-being.36 Therefore, hospitals and physicians should always strive for a service that exceeds the patients’ expectations.

In the patient-physician relationship, patient satisfaction is primarily determined by the provider's interpersonal quality of care, which, among other characteristics, refers to active listening, comforting, and accepting the patient during their interactions.37 In general, it is believed that interventions involving artificial intelligence have the potential to positively affect this interplay.38 These interventions can aid in reducing monotonous and repetitive tasks, allowing providers to focus on developing their relationships with patients.38,39 However, care must also be taken not to harm this relationship.38 For instance, administrators should not view the increase in provider time as an opportunity to schedule more patients per day, as discussed by Nagy and Sisk.38 This would render the intervention meaningless and counterproductive, reducing patient satisfaction and even contributing to a rise in provider burnout.

In the surgical practice, one way of improving patient satisfaction is by providing patients with information regarding their procedure. For example, providing information on postoperative care during the preoperative period to patients undergoing cardiac bypass surgery showed improved patient and family satisfaction.40 Furthermore, a study by Renna et al showed that patients of the orthopedics service who received information on their procedures preoperatively had higher satisfaction scores than those receiving the information postoperatively.41 Therefore, interventions focusing on patient education before a surgical procedure are effective in improving patient satisfaction.

Recently, commercially available AIVAs have been tested for their performance on patient education in both surgical and medical areas. However, their use might be limited to specific tasks (eg, administering cognitive behavioral therapy)42 due to inconsistent and unreliable answers that might endanger patients.43-47 Chung et al hypothesize that this unreliability might be due to each company's policies on health data delivery,44 highlighting the importance of an independent AIVA specifically created for patient education.

The National Academy of Medicine refers to these devices as “Conversational Agents,”48 but the legislation governing them has not kept pace with technological development, making it even more challenging to put this technology into use and highlighting the need for collective evolution. Many physicians may share the present perspective, which is that such systems should be avoided to limit liability.49 This is crucial when making use of AIVAs that support clinical decision-making processes because these might be complicated by medico-legal issues, especially when it comes to safety.50 Since the tort law system favors the standard of care regardless of the result, in situations like these, accepting suggestions that have diverged from the standard of care may expose doctors to liability.49,51 Here lies the significance of testing the implementational features of these products, as identifying potential obstacles can help develop application-specific guidelines for these products’ operation, supporting the dependable, safe, and efficient use of this technology.49

To our knowledge, ours is the first telephone-accessed AIVA that serves the purpose of answering preoperative FAQs. Therefore, data to which we can compare our results are largely limited to the use of this technology for different purposes. Furthermore, because most of the reports on AIVA technology are pilot studies, many focus on the description of the technology rather than the users’ perception of the product. By stratifying patient satisfaction in different areas, Garcia Bermudez et al found high satisfaction scores regarding the improvement of communication with the healthcare team and the voice used to call them when performing follow-up assessments after COVID-19 hospitalization.25 Additionally, “Hello Harlie,” an AIVA created to support patients with Parkinson's disease, received overall positive feedback during a focus group trial but showed problems in the speed of speech processing and the accuracy of its answers.21

Patients agreed that our AIVA was doable, helpful, and easy to use. Eighty-eight percent of patients agreed with the statements of our survey, providing insight into their experiences and opinions on this new technology. Individually, every survey statement surpassed the prespecified agreement level of 75%, except the one about using the AIVA to help choose a surgical procedure. We believe this is due to the patients considering this as a highly complex interaction between them and their surgeon, requiring clear explanations of pros and cons. Furthermore, the gradual shifting of the patient-physician interaction from a paternalistic approach to a shared decision-making process might have influenced the patients’ opinions. This approach allows patients to express their feelings and preferences on the proposed treatment modalities,52 which is currently not possible with AIVA technology. A recent review by Shinkunas et al found that, in the elective setting, most patients and surgeons preferred shared decision-making,53 which supports our results. A study of the opinions of our institution's plastic surgeons on utilizing the AIVA for this purpose could further elucidate our assumption. Additionally, a relevant question that will be included in further versions of the survey for larger cohorts will ask patients if they prefer to speak to a human or to an artificial intelligence, because this is also an important implementational aspect of the AIVA.

One of the comments that caught our attention stated that the patient received different information from the AIVA and the on-site nurse. Specifically, the patient asked about the time for suture removal, to which the AIVA provided the appropriate predetermined response while the nurse had previously mentioned a shorter time. However, on a more profound analysis of this issue, we realized that the nurse had provided the correct answer, considering the type of surgery the patient would undergo. Therefore, although the answers provided by the AIVA serve well as a general guideline, additional features could later include specific answers to different types of surgeries. The addition of answers tailored to surgery type would also solve the problem of the missing questions regarding wearing a bra and wearing a brace.

Our previous pilot experiment showed the AIVA had an accuracy of 90%, with a personnel-evaluated accuracy of 83%.26 In this pilot experiment, patient-evaluated accuracy was 98.5%, considering those answers that were correct and correct but incomplete. This accuracy is equal to or superior to commercially available AIVAs used for different purposes.46,47,54 Only 76.9% of patients considered the answer for nausea correct, while 15.4% considered it correct but incomplete. This provides a total accuracy of 92.3% for this answer. We believe nausea is a substantial concern for patients before surgery, and therefore would like a more detailed answer on its postoperative management. Considering that 2 patients suggested adding tips to decrease nausea to this answer, our hypothesis seems plausible. We expect that adding details to this answer will increase the patient-considered accuracy in future versions of the AIVA.

Despite the vast amount of information available on the Internet, according to studies, it can be difficult for patients to effectively navigate this material.55 Moreover, some physicians may be opposed to this approach. This demonstrates the necessity of providing patients with concise, trustworthy, and accurate information in a straightforward manner.55 It is crucial to provide this information to patients, as nonmedically trained individuals may publish material that they believe to be accurate, which may result in adverse consequences for specific patients.56 Concerningly, the absence of reputable information sources in the top listings of the main search engines is troubling.56 Although some patients establish an organized strategy to searching utilizing, for instance, a variety of keywords, others find it cumbersome and the search results confusing.57 Despite these drawbacks, older persons have found speech conversations to be advantageous; as a result, they may get greater value from these earliest forms of conversational bots.57,58 Although accessing information from traditional websites may be valuable for certain people, others may benefit more from a simpler method, such as conversational bots, for delivering healthcare information.

This study was a pilot project with some limitations. First, only 26 patients participated in the study, and only 24 finished the surveys. Second, because the study protocol required participants to use an on-site phone, they were under the supervision of study personnel. We tried to minimize bias by communicating to patients that their information would be deidentified so they would not feel coerced to answer positively. Lastly, the patients in this cohort are enrolled in a large academic hospital. However, we believe the AIVA could be equally impactful in small practices.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results show that patients were satisfied and expressed a positive experience with using the AIVA to answer plastic surgery FAQs before surgery. They considered the AIVA doable, helpful, and easy to use. They agreed that this system could be used in the future for appointment scheduling, improve their understanding of the surgery, and, most importantly, spend better time with their surgeon. These results add to our previous results on accuracy measurement for administrative personnel and further support the feasibility and encourage implementation of an AIVA for preoperative plastic surgery patients. The analysis of the comments also allowed us to identify key improvement areas, particularly the need to create procedure-specific answers.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the Mayo Clinic Florida Clinical Practice Committee and the Clinical Research Operations Group of Mayo Clinic Florida.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Dr Avila is a postdoctoral research fellow, Division of Plastic Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA.

Dr Boczar is a PGY-1 surgery resident, Department of Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Dr Spaulding is a senior associate consultant, Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, Division of Health Care Delivery Research, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA.

Dr Quest is principal data science analyst, Center for Digital Health, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

Mr Samanta is a data science analyst, Center for Digital Health, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

Dr Torres-Guzman is a postdoctoral research fellow, Division of Plastic Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA.

Dr Maita is a postdoctoral research fellow, Division of Plastic Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA.

Dr Garcia is a postdoctoral research fellow, Division of Plastic Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA.

Dr Eldaly is a postdoctoral research fellow, Division of Plastic Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA.

Dr Forte is an associate professor, Division of Plastic Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA.