-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Peter J Ullrich, Stuti Garg, Narainsai Reddy, Abbas Hassan, Chitang Joshi, Laura Perez, Stefano Tassinari, Robert D Galiano, The Racial Representation of Cosmetic Surgery Patients and Physicians on Social Media, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 42, Issue 8, August 2022, Pages 956–963, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjac099

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Aggregated data show that Black patients undergo disproportionately lower rates of cosmetic surgery than their Caucasian counterparts. Similarly, laboratory findings indicate that social media representation is lower among Black patients for breast reconstruction surgery, and it is expected that this could be the case in cosmetic surgery as well.

The aim of this study was to explore the social media representation of Black patients and physicians in the 5 most common cosmetic surgery procedures: rhinoplasty, blepharoplasty, abdominoplasty, breast augmentation, and liposuction.

Data were collected from RealSelf (Seattle, WA), the most popular social media site for sharing cosmetic surgery outcomes. The skin tone of 1000 images of patients in each of the top 5 cosmetic surgeries was assessed according to the Fitzpatrick scale, a commonly utilized skin tone range. Additionally, the Fitzpatrick scores of 72 providers who posted photographs within each surgical category were collected.

Black patients and providers are underrepresented in rhinoplasty, blepharoplasty, breast augmentation, and liposuction compared with the general population (defined by the US Census Bureau), but were proportionately represented in abdominoplasty. Additionally, it was found that patients most often matched Fitzpatrick scores when both had scores of 2, whereas patients with a score of 5 and 6 rarely matched their provider’s score.

The underrepresentation of Black patients and providers in social media for cosmetic surgery may well discourage Black patients from pursuing cosmetic surgeries. Therefore, it is essential to properly represent patients to encourage patients interested in considering cosmetic surgery.

See the Commentary on this article here.

Cosmetic surgery focuses on enhancing a person’s physical appearance through surgical techniques. Plastic surgeons can perform both noninvasive techniques such as Botox and laser skin treatments as well as surgical procedures such as breast augmentation and rhinoplasty. The latter category requires considerable financial and time commitments on the part of the patient. To justify the risks and commitments of plastic surgery, the mental health benefits have been studied at length to understand how these surgeries influence the psychology of patients. Results show that cosmetic surgery improves quality of life, increases self-esteem, and reduces feelings of depression, all of which are maintained long term.1,2 Improvements in mental health have been specifically referenced in a variety of cosmetic surgical procedures, including breast augmentation, rhinoplasty, and breast reduction.3-6 Cosmetic plastic surgery is gaining popularity, with a 22% increase in total surgeries since 2000.7 The top 5 most popular cosmetic surgeries are liposuction, breast augmentation, rhinoplasty, blepharoplasty, and abdominoplasty, accounting for over 1.3 million surgeries in 2020 which accounted for 56.9% of all cosmetic procedures in the US.7

One contribution to the rise in plastic surgery is the influence of social media. Social media has quickly infiltrated many aspects of Americans’ lives, particularly as a marketing tool for products, places, services, and people. Consequently, plastic surgeons have gravitated toward the use of social media. Those who focus on aesthetic and cosmetic surgery are the most likely to have an active social media account, with 79.4% of aesthetic plastic surgeons utilizing social media compared with the average of 61.9% among all plastic and reconstructive surgeons.8 This is an effective strategy for recruiting patients because studies have shown that social media and other forms of media tend to influence a person’s decision to pursue surgery.9 Social media is particularly influential on patients’ decision to undergo various forms of cosmetic surgery, increasing plastic surgery acceptance across nearly all demographics and cultures, although at different levels.10,11 Plastic surgeons utilize various sites such as Twitter (San Francisco, CA), Instagram (Meta, Menlo Park, CA), Facebook (Meta), and RealSelf (Seattle, WA), the latter being a popular source for both surgeons posting results and patients giving reviews.12 Thus, RealSelf has gained recognition as a prominent source for conducting research on social media use within plastic surgery.13,14

One growing topic of concern across healthcare in the United States is the lack of representation of ethnic and racial minorities. This includes presence in patient populations, workplace hiring, university enrollment rates, etc, and the representation of minority groups in advertising and social media. Montgomery et al highlighted the clear lack of literature regarding patients of color and other studies evaluating differences in skin color appearances among dermatologic studies.15 These findings extend to plastic surgery as well. Particularly in the Black population, there are disproportionately fewer individuals pursuing cosmetic surgery. The US Census Bureau states that 13.4% of the US population is Black; 16 however, only 9% of patients receiving cosmetic surgery are Black.17 Furthermore, the top 4 procedures illustrate an even more significant disparity in Black patients, who represent only 7% of breast augmentation, 6% of rhinoplasty, 3% of blepharoplasty, and 8% of liposuction cases.17 This disparity exists across other forms of plastic surgery, including breast reconstruction. Our laboratory previously showed that dark-skinned individuals were underrepresented on social media platforms where only 6.7% of posts by all plastic surgeons were non-White, as classified by the Fitzpatrick scale.18 Considering the even greater use of social media in cosmetic and aesthetic surgery, we sought to understand if there is an underrepresentation of Black patients in social media posts for the top 5 most common cosmetic procedures. We hypothesized that Black patients are not proportionally represented in social media posts which could contribute to the low number of Black patients seen in these surgeries.

METHODS

Patient Data Extraction

Patient Selection

This study was conducted between December 2020 and December 2021. In order to determine the demographic proportions of patients represented in social media, patient photographs were obtained from the “Procedures” section of the RealSelf website. Photographs were filtered by the following procedure types: rhinoplasty, blepharoplasty, breast augmentation, liposuction, and abdominoplasty. Data for the first 1000 patients on the corresponding procedure web page were extracted for each procedure type.

Data Extraction

The parameters extracted for each result photograph were the patient’s Fitzpatrick score, and the provider’s certification, location, and Fitzpatrick score. Five research team members were trained to evaluate Fitzpatrick scores according to standardized scales and methods to ensure consistency. Training included a session where standard Fitzpatrick scores were shown, and several examples of photographs that fall under each score were displayed to the research team members. The Fitzpatrick score was also recorded for 72 providers who posted photographs.

Patient-Physician Score Match

Methods

The first 72 providers of each procedure were assessed. We chose 72 because the average provider posted roughly 5 photographs of unique patients, resulting in a thorough dataset where, at minimum, over a quarter of gathered patients could be compared to their provider. Patient data were aggregated and grouped by whether the patients’ Fitzpatrick scores matched their providers’ scores for each procedure. The 2 groups were compared to determine if a difference existed for each procedure.

Statistical Analysis

A chi-square test was conducted to compare the proportion of patients who did and did not have a matching Fitzpatrick score to their providers for the 6 possible Fitzpatrick scores. A post hoc test with pairwise comparisons was conducted using the z-test of 2 proportions with a Bonferroni correction to determine the specific differences between scores. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS version 27 (Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Representation in Social Media

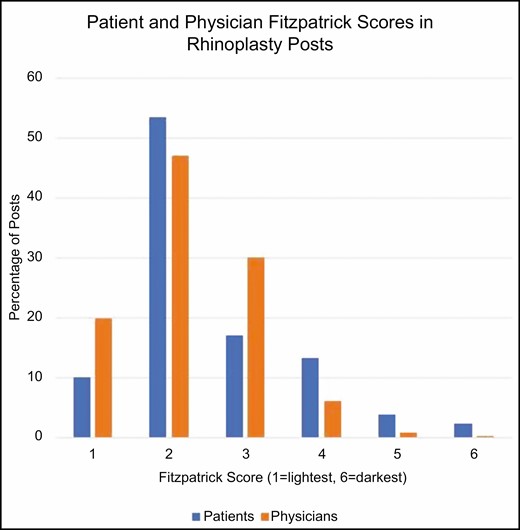

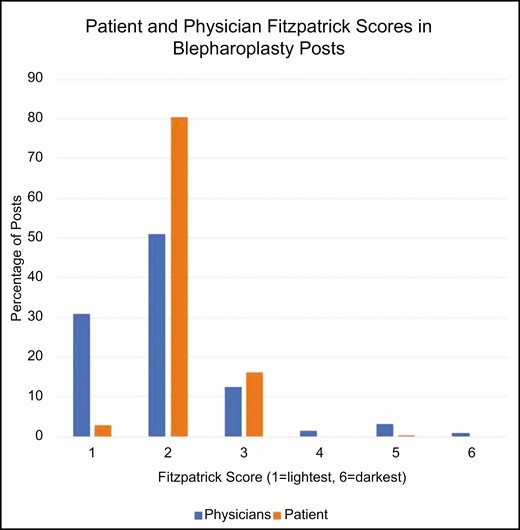

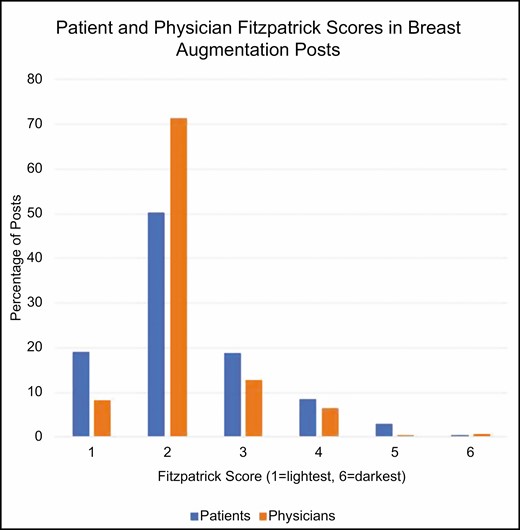

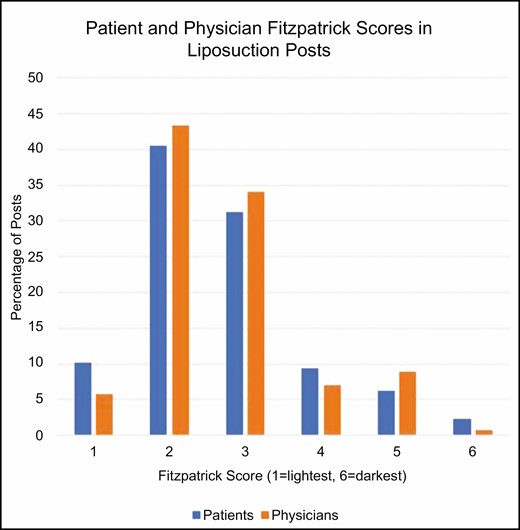

Social media representation for all surgeries can be seen in Figures 1-5 and Tables 1-5. In this study, we define a Black patient or physician as someone with a Fitzpatrick score of 5 or 6. In the rhinoplasty photographs (n = 1000), Black patients made up 6.3% (n = 63) of posted photographs and Black providers made up only 1.1% (n = 5) of posts (Figure 1, Table 1). For blepharoplasty photos (n = 1000), Black patients comprised 4.1% (n = 41) of all photographs, whereas Black physicians covered only 0.3% (n = 1) (Figure 2, Table 1). In breast augmentation surgery (n = 1000), Black patients were 3.4% (n = 34) of all posts, and Black physicians posted 1.2% (n = 7) (Figure 3, Table 2). For liposuction (n = 1000), Black patients were 8.6% (n = 86) of photographs, and Black physicians posted 9.7% (n = 25) of the photographs. Lastly, for abdominoplasty, Black patients were 17.0% (n = 170) of the photographs, and Black physicians covered just 4.3% (n = 15) of all physicians.

Number and Percentages of Patients and Providers Who Fall Under Each Fitzpatrick Score for Rhinoplasty

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 10.00 | 86 | 19.77 |

| 2 | 535 | 53.50 | 205 | 47.13 |

| 3 | 170 | 17.00 | 113 | 25.98 |

| 4 | 132 | 13.20 | 26 | 5.98 |

| 5 | 39 | 3.90 | 4 | 0.92 |

| 6 | 24 | 2.40 | 1 | 0.23 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 435 | 100.00 |

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 10.00 | 86 | 19.77 |

| 2 | 535 | 53.50 | 205 | 47.13 |

| 3 | 170 | 17.00 | 113 | 25.98 |

| 4 | 132 | 13.20 | 26 | 5.98 |

| 5 | 39 | 3.90 | 4 | 0.92 |

| 6 | 24 | 2.40 | 1 | 0.23 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 435 | 100.00 |

Number and Percentages of Patients and Providers Who Fall Under Each Fitzpatrick Score for Rhinoplasty

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 10.00 | 86 | 19.77 |

| 2 | 535 | 53.50 | 205 | 47.13 |

| 3 | 170 | 17.00 | 113 | 25.98 |

| 4 | 132 | 13.20 | 26 | 5.98 |

| 5 | 39 | 3.90 | 4 | 0.92 |

| 6 | 24 | 2.40 | 1 | 0.23 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 435 | 100.00 |

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 10.00 | 86 | 19.77 |

| 2 | 535 | 53.50 | 205 | 47.13 |

| 3 | 170 | 17.00 | 113 | 25.98 |

| 4 | 132 | 13.20 | 26 | 5.98 |

| 5 | 39 | 3.90 | 4 | 0.92 |

| 6 | 24 | 2.40 | 1 | 0.23 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 435 | 100.00 |

Number and Percentages of Patients and Providers Who Fall Under Each Fitzpatrick Score for Blepharoplasty

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 308 | 30.80 | 11 | 3.04 |

| 2 | 509 | 50.90 | 291 | 80.39 |

| 3 | 126 | 12.60 | 59 | 16.30 |

| 4 | 16 | 1.60 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 5 | 33 | 3.30 | 1 | 0.28 |

| 6 | 8 | 0.80 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 362 | 100.00 |

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 308 | 30.80 | 11 | 3.04 |

| 2 | 509 | 50.90 | 291 | 80.39 |

| 3 | 126 | 12.60 | 59 | 16.30 |

| 4 | 16 | 1.60 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 5 | 33 | 3.30 | 1 | 0.28 |

| 6 | 8 | 0.80 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 362 | 100.00 |

Number and Percentages of Patients and Providers Who Fall Under Each Fitzpatrick Score for Blepharoplasty

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 308 | 30.80 | 11 | 3.04 |

| 2 | 509 | 50.90 | 291 | 80.39 |

| 3 | 126 | 12.60 | 59 | 16.30 |

| 4 | 16 | 1.60 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 5 | 33 | 3.30 | 1 | 0.28 |

| 6 | 8 | 0.80 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 362 | 100.00 |

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 308 | 30.80 | 11 | 3.04 |

| 2 | 509 | 50.90 | 291 | 80.39 |

| 3 | 126 | 12.60 | 59 | 16.30 |

| 4 | 16 | 1.60 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 5 | 33 | 3.30 | 1 | 0.28 |

| 6 | 8 | 0.80 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 362 | 100.00 |

Patient and physician scores are both much higher for Fitzpatrick scores of 2 and 3 than for scores of 5 or 6 for rhinoplasty.

Physician Fitzpatrick scores of 2 are much higher than other scores for blepharoplasty.

Patient and physician Fitzpatrick scores hover around a score of 2 most distinctly for breast augmentation.

Patient and physician Fitzpatrick scores are most prominent for a score of 3 for liposuction.

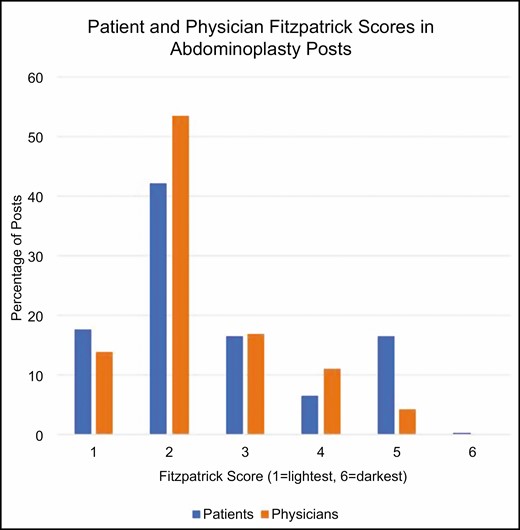

Physician and patient Fitzpatrick scores most common for a score of 2 for abdominoplasty.

Patient-Physician Match of Fitzpatrick Scores

Chi-square analysis revealed significant differences between whether providers and patients had the same or different Fitzpatrick scores, and each specific Fitzpatrick score. For rhinoplasty, the 2 multinomial probability distributions were not equal (χ 2(5) = 68.971, P < 0.001). Observed frequencies of Fitzpatrick scores where patient-provider scores were the same and different are reported in Table 1. Statistical significance for post hoc analysis was accepted at P < 0.05. Rhinoplasty cases where patients and providers both had a Fitzpatrick score of 2 (50.2%) were significantly more numerous than cases where both had Fitzpatrick scores of 1 (23.9%), 3 (22.6%), 4 (3.2%), and 5 (0%), respectively (P < 0.05). Additionally, rhinoplasty cases where patients and providers both had a Fitzpatrick score of 4 (3.2%) were significantly fewer than cases with both having scores of 1, 2, and 3, respectively (P < 0.05).

For blepharoplasty, the 2 multinomial probability distributions were not equal (χ 2(5) = 220.007, P < 0.001). Observed frequencies of Fitzpatrick scores where patient-provider scores were the same and different are reported in Table 2. Statistical significance for post hoc analysis was accepted at P < 0.05. Blepharoplasty cases where patients and providers both had a Fitzpatrick score of 2 (86.5%) were significantly more numerous than cases where both had Fitzpatrick scores of 1 (3.5%), 3 (31.7%), 4 (0%), and 5 (0%), respectively (P < 0.05). Additionally, blepharoplasty cases where patients and providers both had a Fitzpatrick score of 3 were significantly more numerous than cases with both having scores of 1 (P < 0.05).

For breast augmentation, the 2 multinomial probability distributions were not equal (χ 2(5) = 225.562, P < 0.001). Observed frequencies of Fitzpatrick scores where patient-provider scores were the same and different are reported in Table 3. Statistical significance for post hoc analysis was accepted at P < 0.05. Breast augmentation cases where patients and providers both had a Fitzpatrick score of 2 (69.5%) were significantly more numerous than cases where both had Fitzpatrick scores of 1 (11.0%), 3 (8.3%), 4 (10.0%), and 5 (5.0%), respectively (P < 0.05).

Number and Percentages of Patients and Providers Who Fall Under Each Fitzpatrick Score for Breast Augmentation

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 190 | 19.00 | 49 | 8.22 |

| 2 | 503 | 50.30 | 426 | 71.48 |

| 3 | 187 | 18.70 | 76 | 12.75 |

| 4 | 86 | 8.60 | 38 | 6.38 |

| 5 | 29 | 2.90 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 6 | 5 | 0.50 | 4 | 0.67 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 596 | 100.00 |

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 190 | 19.00 | 49 | 8.22 |

| 2 | 503 | 50.30 | 426 | 71.48 |

| 3 | 187 | 18.70 | 76 | 12.75 |

| 4 | 86 | 8.60 | 38 | 6.38 |

| 5 | 29 | 2.90 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 6 | 5 | 0.50 | 4 | 0.67 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 596 | 100.00 |

Number and Percentages of Patients and Providers Who Fall Under Each Fitzpatrick Score for Breast Augmentation

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 190 | 19.00 | 49 | 8.22 |

| 2 | 503 | 50.30 | 426 | 71.48 |

| 3 | 187 | 18.70 | 76 | 12.75 |

| 4 | 86 | 8.60 | 38 | 6.38 |

| 5 | 29 | 2.90 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 6 | 5 | 0.50 | 4 | 0.67 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 596 | 100.00 |

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 190 | 19.00 | 49 | 8.22 |

| 2 | 503 | 50.30 | 426 | 71.48 |

| 3 | 187 | 18.70 | 76 | 12.75 |

| 4 | 86 | 8.60 | 38 | 6.38 |

| 5 | 29 | 2.90 | 3 | 0.50 |

| 6 | 5 | 0.50 | 4 | 0.67 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 596 | 100.00 |

For liposuction, the 2 multinomial probability distributions were not equal (χ 2(5) = 32.515, P < 0.001). Observed frequencies of Fitzpatrick scores where patient-provider scores were the same and different are reported in Table 4. Statistical significance for post hoc analysis was accepted at P < 0.05. Liposuction cases where patients and providers both had a Fitzpatrick score of 2 (47.4 %) and 4 (40.5%) were both significantly more numerous than cases where both had Fitzpatrick scores of 1 (4.2%) and 4 (8.6%), respectively (P < 0.05).

Number and Percentages of Patients and Providers Who Fall Under Each Fitzpatrick Score for Liposuction

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 102 | 10.20 | 15 | 5.81 |

| 2 | 405 | 40.50 | 112 | 43.41 |

| 3 | 313 | 31.30 | 88 | 34.11 |

| 4 | 94 | 9.40 | 18 | 6.98 |

| 5 | 63 | 6.30 | 23 | 8.91 |

| 6 | 23 | 2.30 | 2 | 0.78 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 258 | 100.00 |

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 102 | 10.20 | 15 | 5.81 |

| 2 | 405 | 40.50 | 112 | 43.41 |

| 3 | 313 | 31.30 | 88 | 34.11 |

| 4 | 94 | 9.40 | 18 | 6.98 |

| 5 | 63 | 6.30 | 23 | 8.91 |

| 6 | 23 | 2.30 | 2 | 0.78 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 258 | 100.00 |

Number and Percentages of Patients and Providers Who Fall Under Each Fitzpatrick Score for Liposuction

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 102 | 10.20 | 15 | 5.81 |

| 2 | 405 | 40.50 | 112 | 43.41 |

| 3 | 313 | 31.30 | 88 | 34.11 |

| 4 | 94 | 9.40 | 18 | 6.98 |

| 5 | 63 | 6.30 | 23 | 8.91 |

| 6 | 23 | 2.30 | 2 | 0.78 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 258 | 100.00 |

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 102 | 10.20 | 15 | 5.81 |

| 2 | 405 | 40.50 | 112 | 43.41 |

| 3 | 313 | 31.30 | 88 | 34.11 |

| 4 | 94 | 9.40 | 18 | 6.98 |

| 5 | 63 | 6.30 | 23 | 8.91 |

| 6 | 23 | 2.30 | 2 | 0.78 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 258 | 100.00 |

For abdominoplasty, the 2 multinomial probability distributions were not equal (χ 2(5) = 27.248, P < 0.001). Observed frequencies of Fitzpatrick scores where patient-provider scores were the same and different are reported in Table 5. Statistical significance for post hoc analysis was accepted at P < 0.05. Abdominoplasty cases where patients and providers both had a Fitzpatrick score of 2 (32.1%) were significantly more numerous than cases where both had Fitzpatrick scores of 1 (11.6%), 3 (10.7%), and 5 (7.9%), respectively (P < 0.05).

Number and Percentages of Patients and Providers Who Fall Under Each Fitzpatrick Score for Abdominoplasty

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 177 | 17.70 | 48 | 13.99 |

| 2 | 422 | 42.20 | 184 | 53.64 |

| 3 | 166 | 16.60 | 58 | 16.91 |

| 4 | 65 | 6.50 | 38 | 11.08 |

| 5 | 166 | 16.60 | 15 | 4.37 |

| 6 | 4 | 0.40 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 343 | 100.00 |

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 177 | 17.70 | 48 | 13.99 |

| 2 | 422 | 42.20 | 184 | 53.64 |

| 3 | 166 | 16.60 | 58 | 16.91 |

| 4 | 65 | 6.50 | 38 | 11.08 |

| 5 | 166 | 16.60 | 15 | 4.37 |

| 6 | 4 | 0.40 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 343 | 100.00 |

Number and Percentages of Patients and Providers Who Fall Under Each Fitzpatrick Score for Abdominoplasty

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 177 | 17.70 | 48 | 13.99 |

| 2 | 422 | 42.20 | 184 | 53.64 |

| 3 | 166 | 16.60 | 58 | 16.91 |

| 4 | 65 | 6.50 | 38 | 11.08 |

| 5 | 166 | 16.60 | 15 | 4.37 |

| 6 | 4 | 0.40 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 343 | 100.00 |

| Fitzpatrick score . | Patient count . | Patient percent . | Physician count . | Physician percent . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 177 | 17.70 | 48 | 13.99 |

| 2 | 422 | 42.20 | 184 | 53.64 |

| 3 | 166 | 16.60 | 58 | 16.91 |

| 4 | 65 | 6.50 | 38 | 11.08 |

| 5 | 166 | 16.60 | 15 | 4.37 |

| 6 | 4 | 0.40 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 1000 | 100.00 | 343 | 100.00 |

Discussion

Proper representation of racially and ethnically diverse individuals across social media platforms is an important topic to address in a multicultural nation such as the United States. People often base their decisions on their relatability to marketable content that consists of demographic factors such as skin tone.19,20 Our study illustrates that dark-skinned populations, as defined by individuals with Fitzpatrick ratings of 5 and 6, are underrepresented in 4 of the top 5 most popular plastic surgery cosmetic surgery procedures in the United States. Similarly, Black physicians represent an extremely small presence on social media, which could be further accentuating the issue of a lower percentage of Black patients. These disparities are based on the fact that the US Census Bureau shows that 13.4% of the US population is Black.16

Although Black patients are underrepresented compared with the general population, the results indicate that the percentage of dark-skinned populations similarly reflects the percentage of Black people who actually pursue the respective surgeries. Black people account for 6% of surgeries in rhinoplasty and appear in 6.3% of social media posts. For blepharoplasty, Black people make up 3% of the surgical population and 4% of the social media posts. Liposuction has a Black population of 8% whereas 8.6% of posts are Black patients. Breast augmentation sees 7% of Black people as the population with only 3.4% of social media posts. Abdominoplasty is the only overt overrepresentation in social media where the procedure has 12% Black people and shows 16.7% in social media. Participation of Black patients in surgery is therefore reflected in social media. Due to the influence of social media on people’s decision-making, we expect that an underrepresentation of Black people in social media maintains a low participation in these surgeries, causing a vicious cycle of low numbers within these surgeries.

The skin tone of the plastic surgeon can also influence a patient’s decision to undergo surgery as patients tend to gravitate towards providers who look like them physically. One study demonstrated that African Americans, in particular, were more willing to travel greater distances to find a surgeon who shares their ethnicity or race when pursuing cosmetic surgery.21 Our study found that Black physicians have a relatively low presence in all 5 cosmetic procedures. This study then assessed whether patient and provider Fitzpatrick scale correlated significantly. The results differed among each procedure, but our results consistently demonstrated that Fitzpatrick scores matched most often for patients and physicians who had a Fitzpatrick score of 2, whereas patients with scores of 5 or 6 rarely had the same Fitzpatrick score as their provider. Of note, significant differences could not be established on several instances because the numbers of physicians with scores 5 and 6 were not adequate to prove significance.

The data on physician-patient matching could be another determinant of the phenomenon we see in social media representation. Black physicians are underrepresented on social media platforms, which is likely a reflection of the field itself. A report in 2008 by Butler et al illustrated the lack of ethnic diversity in plastic surgery: 68.7% of US plastic surgery fellows and residents are White, with Asians comprising 20.9%, African Americans 3.7%, and Latinx-Americans 6.2%.22 Furthermore, academic plastic surgeons attending physicians break down to 74.9% Caucasian, 10.9% Asian, 1.4% African American, and 3.6% Latinx (the remaining physicians were predominantly international practitioners).22 A more recent study showed that between 1995 and 2014, the demographics for plastic surgery residents changed significantly for Asian and Hispanic residents, but not for African American residents. While Asian residents increased approximately 3-fold (from 7.4% to 21.7%, P < 0.001) and Hispanic residents approximately 2-fold (from 4.6% to 7.9%, P < 0.001), African American residency numbers did not significantly increase (from 3.0% to 3.5%, P = 0.129).23 The lack of dark-skinned practitioners is reflected in the social media presence numbers we collected. Having a low number of Black physicians in the field unsurprisingly results in lower social media presence. We believe these factors contribute to the underrepresentation of Black individuals in both social media and overall patient demographics for those who pursue cosmetic surgeries.

Data are still lacking on whether patients pursue surgery more readily if they see posts on social media containing people of similar demographics. However, we suspect that social media presence impacts patients’ desire to undergo cosmetic surgery. Therefore, by demonstrating the state of social media representation, we hope to encourage plastic surgeons to adjust their social media posts to represent patients from various racial backgrounds more adequately.

Limitations

Our laboratory decided to utilize only RealSelf in our analysis because this is the primary site for leaving reviews and comments as both a patient and physician. Therefore, neglecting other popular formats such as Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter could result in missing several prominent physician and patient representations. Next, although we originally attempted to use hex color code scores to objectively verify Fitzpatrick scales, the objective hex scores were often influenced by the variable lighting or camera setups of different physicians. Therefore, Fitzpatrick scores were our primary data outcomes, and this could result in different determinations by our 5 reviewers. Regarding the physician-patient match statistics, and as mentioned previously, there is a small representation of dark-skinned individuals on social media, so our ability to establish significance among provider matches was limited in several instances, specifically for scores of 5 and 6. Another limitation is that our team did not collect information on the age range or gender of the patients, and these data could reveal particular differences in representation within these categories.

One important limitation is that we are unable to compare a physician’s actual practice against their social media posts. This would require having full access to each physician’s patient data including the Fitzpatrick score of the patient as well as gathering each social media post the physician has made. Further studies could truly compare the proportion of Fitzpatrick scale 5 and 6 patients within specific practices against the proportion of those posted on social media to understand if a disparity exists between those receiving surgery and those being represented.

Conclusions

Black patients (Fitzpatrick scores of 5 and 6) and physicians are underrepresented on the most popular social media platform for plastic surgery compared with the general US population. Blepharoplasty, abdominoplasty, breast augmentation, liposuction, and rhinoplasty are the five most common cosmetic procedures in the United States, and Black patients are underrepresented on social media in all but abdominoplasty. Similarly, patient-physician matching of Fitzpatrick scores is less frequent in Black individuals, largely due to a lack of Black physicians. This reflects the greater issue of lack of Black plastic surgeons, and, because patients tend to pursue care from physicians who share the same ethnicity and/or race, we believe the lack of Black plastic surgeons contributes to the underrepresentation in social media we see. Further studies should investigate if patients are directly influenced to pursue cosmetic surgery by the ethnicities and races of those who appear in social media posts. Additionally, future research can investigate if factors such as socioeconomic status, culture, or others influence the data showing a lack of Black patients pursuing cosmetic surgery.

Disclosures

Dr Galiano reports a topically related relationship to MTF Biologics (Edison, NJ) for the use of their cadaveric cartilage (Profile) in rhinoplasty surgeries. The principal investigator (PI) received financial support and was provided cartilage in a previous study. This relationship is not directly related to the current study. The PI also reports a topical relationship to Scarless Laboratories Inc. (Los Angeles, CA) for the use of their investigational drug (SLI-F06) in the study of abdominoplasty scarring. The PI received financial support and was provided SLI-F06 in the previous study; the relationship is not directly related to this study. The remaining authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.