-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

David M Turer, Al Aly, Seromas: How to Prevent and Treat Them—a 20-Year Experience, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 42, Issue 5, May 2022, Pages 497–504, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjab394

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Seromas are a common complication in plastic surgery. In this article, the authors describe their approach to the prevention and treatment of seromas and include a discussion of the evolution of their techniques. They provide specific technical details for many body contouring operations, including abdominoplasty, belt lipectomy, brachioplasty, and thighplasty. Many of the authors’ techniques question the traditional dictums of plastic surgery, and they hope to encourage others to consider novel techniques for the treatment and prevention of seromas.

Seromas are a common complication in almost all surgical specialties. In plastic surgery they occur with regularity, especially in body contouring procedures.1-4 Our approach to the prevention and treatment of seromas has evolved significantly over our careers, which we will share with the reader along with discoveries that contradict many of the old dictums that many plastic surgeons are taught.

For over 20 years, we (especially the senior author) have had to manage a significant number of seromas, particularly in the massive weight loss patients in our practice. For the first 10 years of practice, attempts to reduce seromas were based on the extensive use of multiple drains that were left in place for extended periods of time. Unfortunately, this approach was not very successful and led to a great deal of time working with drains and seromas postoperatively. The purpose of this paper is to share our experience and progression in preventing and treating seromas in over 2 decades of practice.

In addressing a large number of seromas, we discovered that some of what is taught about seromas is not true, as enumerated in Table 1. The first thing we learned was that if one aspirates a seroma once a week, it is much less likely to resolve than if it is aspirated every 2 to 3 days. We also became aware that if a fluid collection was small and not increasing in size, it can be observed and will often resolve without treatment. Probably the most fallacious fact that we discovered is that a seroma capsule must always be excised. Our experience demonstrated in many situations where we had to reoperate on an area of previous surgery, for reasons other than a seroma, there was a capsule present but it was empty. Lastly, we also noted that when we did excise a seroma capsule, it was not an effective means of preventing recurrence.

| Claim | |

| 1. | Infrequent aspiration is effective |

| 2. | Small non-expanding seromas must be treated |

| 3. | A seroma capsule must be removed |

| 4. | Excision of a seroma capsule is an effective treatment |

| Claim | |

| 1. | Infrequent aspiration is effective |

| 2. | Small non-expanding seromas must be treated |

| 3. | A seroma capsule must be removed |

| 4. | Excision of a seroma capsule is an effective treatment |

| Claim | |

| 1. | Infrequent aspiration is effective |

| 2. | Small non-expanding seromas must be treated |

| 3. | A seroma capsule must be removed |

| 4. | Excision of a seroma capsule is an effective treatment |

| Claim | |

| 1. | Infrequent aspiration is effective |

| 2. | Small non-expanding seromas must be treated |

| 3. | A seroma capsule must be removed |

| 4. | Excision of a seroma capsule is an effective treatment |

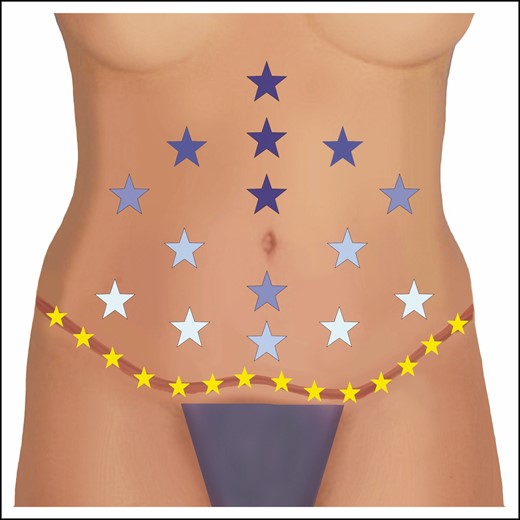

Spurred on by the fairly constant barrage of seromas in our practice, we started to look for means of reducing their occurrence. Fortunately, throughout our careers, we have been exposed to many South American and European plastic surgeons as well as the work of the Pollocks and their utilization of quilting/progressive tension sutures.5-8 Based on the above, we started to introduce progressive tension sutures in abdominoplasty as well as the anterior aspects of belt lipectomy. Figure 1 demonstrates the pattern of progressive tension suture placement in the anterior abdomen. The most obvious result of these changes was a significant reduction in drain output and a decrease in the time to drain removal. We also added another preventive measure, which consisted of placing patients on a small dose of diuretics for 30 days after surgery. We had come to employ diuretics based on noticing that patients who were significantly overhydrated had increased drain outputs. When we reduced these patients’ fluid intake to normal hydration, their drain outputs dropped as well. We then extrapolated that adding a diuretic may further decrease potential seroma fluid and started adding that to the regimen. We initially placed patients on the diuretic for 3 days after the last drain was removed but noted that fluid collected after the discontinuation. Thus, we decided we would keep the patients on the diuretic for an extended period of time to avoid this problem. We now utilize 25 mg of hydrochlorothiazine daily for 30 days, which we realize is arbitrary, but we have not veered from that since we started this practice. We have utilized diuretics for over 10 years. It must be said that we have not conducted any controlled studies to definitively prove the efficacy of diuretics in reducing seromas or the ideal length of time that patients should be placed on them. A relatively small study investigating the utilization of postoperative hydrochlorothiazide demonstrated a reduction in drain output.9 However, larger studies are needed to confirm efficacy and safety.

The authors’ placement of progressive tension/quilting sutures is shown in this diagram. Each star represents an interrupted stitch. Darker colored stars indicate earlier placement and lighter colors indicate subsequent placement. Note the final closure at the scar level is also quilted by incorporating Scarpa’s fascia from the superior and inferior edges as well as the underlying muscle fascia (shown in yellow). Sometimes the authors will utilize a running barbed suture for the abdominal scar closure rather than individual interrupted sutures.

We have always utilized compression garments after surgery, but we are not sure of their efficacy in reducing seromas. If compression garments were completely benign with no potential downside, we would not question utilizing them. However, we believe they are not completely benign, and it is possible that they may have unintended negative effects. We do not utilize direct contact compression garments in the immediate postoperative period without an intervening layer of foam to distribute the pressure more evenly, leading to less likelihood of skin injury and/or necrosis. Another potential problem, which relates to compression in the area of the abdomen, is whether it may have a deleterious effect on blood flow within the femoral venous system, potentially increasing the risk of deep venous thrombosis and/or pulmonary emboli. Fabio Nahas has performed multiple studies investigating the effects of abdominal compression, and he has determined that the application of a compression garment causes the greatest increase in intra-abdominal pressure rather than the abdominal wall plication.10 This does not automatically imply that this leads to more deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary emboli risk, because those studies have not been performed yet, but it may turn out to be an important factor. Thus, when we utilize garments postoperatively, we endeavor to avoid overly aggressive compression, especially in the abdomen.

As our experience grew with progressive tensions sutures and the utilization of diuretics, we eventually eliminated the utilization of drains from our anterior only abdominoplasties. We have been performing abdominoplasty for over 10 years now without drains utilizing the protocol described above, and, in that time, we have experienced only 1 small seroma in an area that we chose not to quilt because we were concerned about the overlying skin’s vascular supply. This is a remarkable change in our seroma rate considering the number of abdominoplasties we perform.

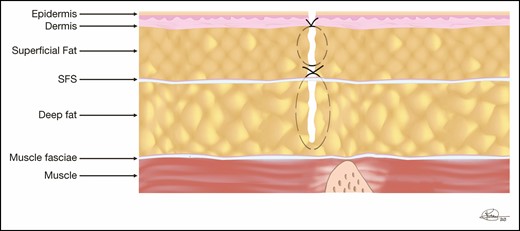

In circumferential belt lipectomies, we eliminated the utilization of drains anteriorly but continued to place posterior drains because, in our practice, the overwhelming majority of the seromas occurred posteriorly. We also felt we could not quilt the posterior incision as we did anteriorly. However, buoyed by the success with abdominoplasty and how much patients appreciated not having a drain, we wanted to determine if the posterior drain could be eliminated. Thus, we devised a closure technique that closes as much dead space as possible, which is different from progressive tension sutures technically but conceptually accomplishes the same goal: closure of as much dead space as possible. This involves leaving a small amount of fat on the posterior muscle fascia and closing the deep layer, approximating the superficial fascial system of the upper and lower aspects of the resection to that deep layer of fat. A second, more superficial layer incorporates from the superficial fascial system level to just below the dermis. This is demonstrated in Figure 2. In both of these layers, sutures are placed every 1 to 2 cm so that when closure is complete, the surgeon cannot pass a finger at any point down to the level of the underlying muscle fascia. We should note that in other parts of the body, we do incorporate a bite of the deep fascia, but have found that the fascia of the lower back is quite rigid and the sutures would tear when trying to tie down to it. This is why we suture the superficial fascial system to this layer of fat instead of the fascia. The dermal and skin closures are routinely closed utilizing any technique the surgeon prefers. Closing in this manner leaves no room for drains, thus eliminating the utilization of drains entirely. Although we have not completely eliminated seromas from occurring after our circumferential belt lipectomies, our prevalence has dramatically decreased, even in some high BMI patients, who traditionally have a high rate. It must be noted that when we initially switched to a no-drain technique, some patients developed lateral seromas because we did not emphasize reducing dead space laterally. Subsequently, all potential spaces are treated aggressively, and this has resulted in further reduction of seromas. In the last 3 years, we have not utilized drains in any belt lipectomy, with a dramatic reduction in our seroma rate, much less than the rate we experienced when drains were utilized. We do not have actual statistics because of how often the senior author’s practice has moved over his career, and the previous practices that he belonged to will not share their records or have closed. However, prior to the elimination of drains, seromas were encountered in at least 30% to 50% of patients overall and 100% in patients presenting with BMIs above 35 kg/m2. After utilizing the above-described technique, the rate is noticeably lower, possibly as low as 5% in all patients, including those with a BMI > 35. Given the significant reduction in morbidity we have observed by utilizing these techniques, we feel it would be unethical to conduct a prospective study of the utilization of drains. We might suggest that an institution that still utilizes drains during their body contouring procedures adopt some or all of our suggested techniques to compare with their current experience.

The back closure in a belt lipectomy is shown in this diagram. The deep layer incorporates the small amount of fat left on the underlying muscle and both the superior and inferior superficial fascial system (SFS). The superficial closure spans from the SFS to the subdermis, closing as much dead space as possible.

Reducing Seromas in Other Areas

Given our success in eliminating drains while substantially reducing our seroma rate in the lower trunk, we have applied these techniques to other areas of the body. In fact, we currently do not employ drains in any body contouring procedures, including arms, thighs, and upper trunk.

Arms

We have not utilized drains during brachioplasty for over 15 years. In our experience, seromas after brachioplasty tend to occur later in the postoperative period, at 5 to 8 weeks postoperatively, and are almost always located just proximal to the elbow. Our approach to reducing seromas is again based on closing as much dead space as possible. To accomplish this, the underlying muscle fascia is incorporated into a suture that approximates all tissues up to the level of the subdermis. These sutures are placed every 1.5 to 2 cm, again leading to minimal dead space. Although seroma position and type may vary based on the particular brachioplasty technique utilized by the surgeon, we believe that closing dead space is a universal approach to seroma prevention no matter the technique. We also do not wrap the arms or employ any significant compression after brachioplasty. The exception to this is when brachioplasty is performed as part of an upper body lift. In that situation, a garment without underlying foam, usually a vest with below-elbow extensions, is utilized that is not too tight on the arms. We again utilize 30 days of postop diuretics as described above. We have not eliminated seromas after brachioplasty completely, but they are greatly reduced.

Thighs

We have also abandoned the utilization of drains during thighplasty. As in the arms, seromas tend to occur 5 to 8 weeks postoperatively and are almost always located just proximal to the knee. In the thighs, we utilize fairly aggressive preexcisional liposuction of the area to be resected, then essentially remove the skin after in the hopes of leaving as many lymphatics behind as possible. The closure itself is identical to that described for the arms above, although it is not always as clear that the deep fascia is incorporated because there is a lot of intervening “honeycomb” post liposuction tissue. Just as in brachioplasty, we also place the patients on 30 days of the postoperative diuretics. However, we do employ aggressive compression in the thighs.

Upper Trunk

We do not utilize drains when performing upper body lifts, which includes upper back, lateral chest, and breast/chest areas. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss upper body lift techniques, but suffice it to say that we follow the same approach of closing dead space wherever we create it. The only area where we do not actively close dead space is in female breast reductions, mastopexy, or augmentation mastopexy. We do employ compression with upper body lifts and 30 days of postoperative diuretics, as described above.

Treatment of Seromas

Despite a significant reduction in our seroma rate over 2 decades of practice, they still occur and must be dealt with. During our first few years of practice, we treated seromas in the more traditional manner of performing serial aspirations once a week. If that was not successful, we would then place a drain. Finally, if ongoing drainage failed to resolve, we would return to the operating room and excise the capsule. This algorithm was significantly work intensive and often disappointing in its results, with a high rate of recurrence after surgical intervention. Based on trial and error and a constant search for improvement, we then developed the method described below.

Seroma Treatment Method #1

We have utilized this technique over the last 20 years with great success. Since we began to employ this method, no patient of ours has required reoperation to treat a seroma.

Identify a seroma as a growing fluid collection. If the patient presents with a small non-expanding seroma, usually in the distal arm or thighs, we would observe it and often it will resolve on its own. If it did not, then we would follow the steps below.

Start with serial aspiration every 2 to 3 days because we noticed that the longer we waited between aspirations, the more likely the seroma did not resolve. This is combined with external compression. Currently we are experimenting with “external net” compression, which will be described below. If the amounts aspirated are not decreasing after a number of attempts, then we move to the next step.

Next, we inject an astringent into the pocket after aspiration, which we will leave in place for 10 to 15 minutes, then aspirate. Again, this regimen is repeated every 2 to 3 days combined with compression. The astringent that we employ is doxycycline, which is available in powder form and can be diluted to different amounts based on the volume of fluid needed to bathe the entire pocket. We have not found the actual concentration to be critical and typically utilize a single 100-mg vial diluted into a volume that will adequately bathe the entire seroma cavity. We typically inject this into the seroma cavity, wait several minutes, and then aspirate that fluid and place the patient in light compression before they leave the office. If this is not successful after several attempts, then the next step is undertaken.

Almost all seromas are located so that opening a small amount of the original closure will allow entry into the pocket. Thus, we will make a 1- to 1.5-cm opening in the incision, place a Penrose drain into the pocket, and sew it in place at the skin. This is combined with compression. Sometimes we will place doxycycline in the pocket as well. We will leave the Penrose drain in place for as long as required for the pocket to close around it, which may require up to 4 to 6 weeks but may require much shorter periods of time depending on the original size and location. We will usually see the patient once a week in this period and ask them to keep track of how much drainage is collecting on the dressing. We do not initially place the patients on antibiotics, but some will become colonized with bacteria and we will then place them on oral antibiotics. It is our impression that this colonization process seems to speed up the closure of the pocket around the Penrose drain but have no scientific proof that it does. We believe this strategy prevents an infection of the cavity while allowing for resolution of the seroma.

It must be stressed that sometimes we will employ some of these steps out of order depending on how far away the patient lives, how cooperative and able they are, and the anatomic location of the seroma. In any case, the last step of placing a Penrose drain and leaving it for as long as is required to close the pocket has been universally successful for us in eliminating seromas without reoperating.

It should be noted that we have never encountered a patient who would prefer to return to the operating room to treat a recalcitrant seroma, with the incumbent cost in money and time, than to undergo the above regimen. If we did, we would not simply remove the capsule and hope that the seroma not recur. We would abrade the seroma capsule and/or have parts of it resected, irrigate the pocket with doxycycline, quilt its walls aggressively closing as much dead space as possible, not employ drains, utilize moderate postoperative compression, and place them on a mild diuretic, as discussed above.

Seroma Treatment Method #2

Roughly 3 years ago, we were introduced to the following technique.11 The steps include:

Recognize the seroma.

Aspirate it but leave the needle tip in the pocket.

Through that needle we typically inject 40 mg of Kenalog (triamcinolone acetonide) diluted with an appropriate volume to bathe the entirety of the seroma cavity with the intent of leaving a thin layer of steroid containing fluid in the pocket. We have not found that a particular concentration of the steroid is required.

External compression via an external net (discussed below) or an external bolster can then be applied. Alternatively, compression with foam and an overlying garment can be utilized. In case of a bolster or external net, the patient will need to be seen within 3 to 4 days for bolster/suture removal to prevent permanent suture marks.

Repeat the above sequence once a week. The net is only utilized with the first attempt.

We have utilized this second method over a much shorter period, and although it has been rather successful, we cannot yet speak to its true success rate. We hypothesize that seromas form because of an inflammatory process resulting in fluid production.12 The steroids reduce inflammation, which theoretically leads to a reduction in fluid production. This proposed mechanism has not been proven or disproven. Studies need to be conducted to determine efficacy over a larger number of cases and effectiveness in different kinds of seromas as well as prove or disprove the proposed mechanism.

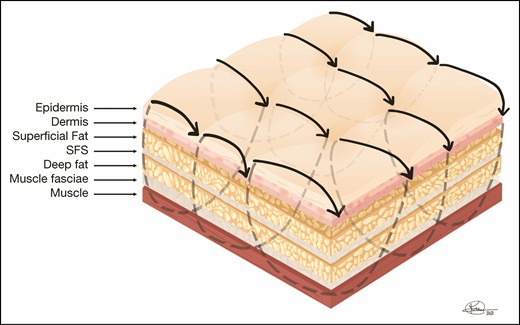

External Netting

External netting is a technique introduced and popularized by Auersvald from Brazil, which closes dead space in a fairly aggressive manner by placing a running suture through the skin that catches the underlying muscle fascia and covers an area that has been operated on during a surgical procedure.13,14 The typical situation in which the external net is utilized is during facelifts, where the entire area of skin elevation is “netted,” usually covering the entire neck and the areas of the cheeks where skin was elevated. Because the sutures are placed transcutaneously, they must be removed within 3 to 4 days to prevent permanent marks but can be effective in preventing fluid accumulation or seroma. Figures 3 and 4 show diagrams of external netting utilized to close dead space. It must be stressed that although this technique has been utilized by other surgeons, the authors have very limited experience with it. In the few cases we have utilized it, which are limited to the neck, male chest in gynecomastia reduction, and creating an infra-mammary crease in a female breast, it has been helpful and we have not experienced any complications. However, as with any other new technique, it will need to be vetted for benefits and complications. Thus, it is not our intent to recommend this technique, and we hope that the reader will educate himself or herself about it before trying it.

External netting sutures are placed through the skin and reach the underlying muscle fascia, usually placed in a running fashion, and are left in place between 3 to 4 days to prevent stitch marks if left in longer. They cover the entire area operated on to close dead space and prevent fluid accumulation as well as contract skin to the underlying anatomy. SFS, superficial fascial system.

An example of the utilization of “external netting” is shown in this diagram. After the medial thighs are liposuctioned and the surgeon wants to increase the contraction of the skin and prevent fluid accumulation, external netting can be utilized. External netting can be employed with closed procedures such as the one shown here as well as open procedures such as facelifts, open gynecomastia procedures, etc. In the case of thigh reduction surgery, the netting would only involve the surface area that has been operated on.

DISCUSSION

Despite innumerable advances in technology and techniques, seromas remain a challenging problem for many plastic surgeons. A 2016 review of over 7000 patients across a wide variety of procedures demonstrated wildly different seroma rates despite numerous interventions.2 Another review of 1824 abdominoplasties demonstrated seroma rates ranging from 1% to 57%, averaging roughly 10%.3 These studies demonstrate that although many techniques may hold promise for reducing seromas, none are by any means a perfect solution.

One major limitation of this manuscript is the lack of objective data to support our statements. The senior author has moved multiple times throughout his career, and as such, we are unable to compile an objective data set. We also fully acknowledge that prospective trials remain the gold standard for clinical studies; however, we still believe there is significant value in our experience. Over a career, we have observed an unquestionable improvement in seroma rates employing the techniques described above as well as very sound approaches to treating seromas once they occur.

Areas of Future Research

We would understand if others are hesitant to take our experience purely on faith and would suggest that studies need to be conducted in a number of areas to further the science involved in the prevention and treatment of seromas. To that end, we suggest some important questions that need to be answered. Although there is good evidence in the literature supporting the utilization of progressive tension sutures and the reduction of dead space in general, in the prevention of seromas there are issues yet to be resolved. These include:

What is the minimum number of sutures that will be effective in seroma prevention of the abdomen?

Alternatively, is it possible that the critical issue is not the number of sutures, but that there is a maximum surface area of dead space above which seromas will increase?

What is the ideal suture material to utilize for quilting?

Can we confirm the benefit of the utilization of diuretics and if so, what is the minimum period of time that they should be utilized?

Are there better drugs than hydrochlorothiazide?

Additionally, because seromas appear to be at least in part mediated by inflammation and given that we have found significant improvement in seromas after steroid injection, it would be very helpful to delineate the following:12

What is the actual composition of the different kinds of seromas clinically encountered? For example, post-abdominoplasty seromas are likely to have a different makeup from seromas that occur after mastectomy.

Is inflammation a true contributing factor in seroma formation?

Which inflammatory factors play a part in the formation of seromas (because there are many that may or may not contribute)?

Do steroids eliminate seromas based on an anti-inflammatory mechanism?

CONCLUSIONS

Improvements in surgical technique have decreased our rate of seromas significantly. Eliminating as much dead space as possible with suture techniques has nearly eliminated seromas from our practice. When a seroma does occur, several new techniques have proven very effective in treating them while avoiding prolonged morbidity or returns to the operating room.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES