-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jessy Hansen, Susannah Ahern, Pragya Gartoulla, Ying Khu, Elisabeth Elder, Colin Moore, Gillian Farrell, Ingrid Hopper, Arul Earnest, Identification of Predictive Factors for Patient-Reported Outcomes in the Prospective Australian Breast Device Registry, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 42, Issue 5, May 2022, Pages 470–480, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjab314

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are an important tool for evaluating outcomes following breast device procedures and are used by breast device registries. PROMs can assist with device monitoring through benchmarked outcomes but need to account for demographic and clinical factors that may affect PROM responses.

This study aimed to develop appropriate risk-adjustment models for the benchmarking of PROM data to accurately track device outcomes and identify outliers in an equitable manner.

Data for this study were obtained from the Australian Breast Device Registry, which consists of a large prospective cohort of patients with primary breast implants. The 5-question BREAST-Q implant surveillance module was used to assess PROMs at 1 year following implant insertion. Logistic regression models were used to evaluate associations between demographic and clinical characteristics and PROMs separately by implant indication. Final multivariate risk-adjustment models were built sequentially, assessing the independent significant association of these variables.

In total, 2221 reconstructive and 12,045 aesthetic primary breast implants with complete 1-year follow-up PROMs were included in the study. Indication for operation (post-cancer, risk reduction, or developmental deformity) was included in the final model for all reconstructive implant PROMs. Site type (private or public hospital) was included in the final breast reconstruction model for look, rippling, and tightness. Age at operation was included in the reconstruction models for rippling and tightness and in the aesthetic models for look, rippling, pain, and tightness.

These multivariate models will be useful for equitable benchmarking of breast devices by PROMs to help track device performance.

See the Commentary on this article here.

Real-time, long-term monitoring of breast device outcomes through clinical quality registries is crucial to ensuring device safety and satisfactory patient outcomes. Previous breast device registry publications have focused on reporting surgical procedure and device type trends,1,2 or clinical outcomes such as revision surgery, complications, and cancer incidence.3-6 Recently, however, the importance of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) as a health outcome has been recognized and PROMs are increasingly being used as clinical quality indicators within clinical registries, including medical device registries.7

PROMs have often been evaluated in addition to clinical outcomes outside of a registry context in studies investigating outcomes following breast device surgery, with a module of the validated BREAST-Q questionnaire being used by many studies.8,9 Most studies evaluating PROMs in breast device recipients have been conducted in populations of reconstructive breast surgery patients,9 often involving cohorts of breast cancer patients.10 Few studies have investigated PROMs following aesthetic breast surgery, including cosmetic augmentation.9,11

Recently the BREAST-Q implant surveillance (IS) module was developed from the broader BREAST-Q for the purpose of breast device performance monitoring, specifically in device registries. The module uses 5 questions from the satisfaction with breasts and physical well-being domains that were found to be the most likely to predict the need for revision surgery.12 Although the BREAST-Q IS has been found to have good retest reliability within an Australian registry setting,13 no studies to date have evaluated the module as a clinical quality outcome.

Benchmarking of PROMs can serve a number of purposes. The benchmarking of device outcomes is a valuable tool for the identification of potentially underperforming devices. Benchmarked PROMs can also be used to compare sites and surgical techniques, and may have the ability to provide an early warning signal for adverse clinical outcomes, such as revision surgery, in addition to evaluating the experience of the device recipient. PROMs have been endorsed by the International Collaboration of Breast Registry Activities (ICOBRA) as a clinical quality indicator for global benchmarking of breast device surgery within registries.14

To accurately identify performance outliers and control for confounding factors, appropriate risk adjustment of benchmarking analyses is necessary.15-17 To date no studies have developed PROM risk-adjustment models following breast device surgery for the purposes of benchmarking. The development of such risk-adjustment models that adequately adjust for confounding is important to ensure equitable benchmarking of PROM data, in which devices, sites, and surgical techniques are not penalized for factors outside of their control. It will also provide a reproducible method for selecting variables that can facilitate international comparisons. This study aims to identify factors associated with PROMs following breast implant procedures within reconstructive and aesthetic procedure cohorts from which to develop risk-adjustment models for the purpose of equitable benchmarking of devices.

METHODS

Data

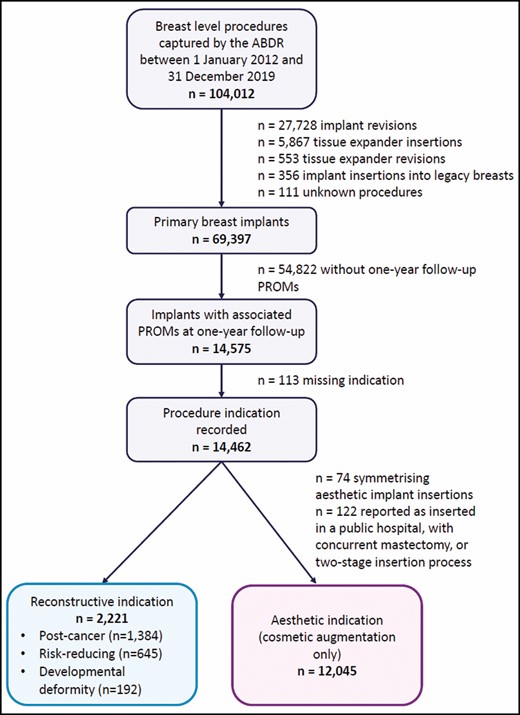

Data for this study were obtained from the Australian Breast Device Registry (ABDR), which collects patient, surgical, and outcome information pertaining to breast device insertion and revision procedures occurring at participating sites across Australia with a patient opt-out consent model. Data included in this study were extracted on April 18, 2020 and relate to breast-level procedures captured by the ABDR between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2019. The process to determine which breast implants were included in the study is outlined in Figure 1.

Implants for which the initial insertion procedure into a primary breast was captured by the ABDR, had an associated complete 1-year follow-up PROM questionnaire, and a recorded procedure indication were eligible for inclusion in the study. Patient-level PROM responses were linked to both breast implants in the case of bilateral insertion procedures. The ABDR began collecting PROMs in 2017 and therefore breast implants inserted between October 2016 and December 2018 were eligible for PROM 1-year follow-up at the data cut-off date. The study period allows for sufficient follow-up time to administer the PROM questionnaire at 1 year following the insertion procedure. We believe this sample size to be sufficient for the analyses; including 2020 may confound the results due to the COVID-19 pandemic affecting the quality of data for that year—hence, more recent data were not included in the analysis. Breast implants with an aesthetic indication inserted as a symmetrizing procedure (an aesthetic implant inserted bilaterally with an implant for reconstruction on the other side) were excluded. Aesthetic breast implants reported as inserted in a public hospital, during a concurrent mastectomy procedure, or in a 2-stage implant process were also excluded. The final cohorts for analysis were breast implants with a reconstructive indication (including post-cancer, risk reduction, and developmental deformity) and implants with an aesthetic (cosmetic augmentation only) indication.

Demographic and Clinical Information

Demographic and clinical data are recorded by surgeons or hospital staff at the time of procedure. This includes patient age, procedure site information, and date of operation. Relevant procedure details are also reported at the breast level including previous radiation therapy (postoperative radiation use is not recorded), use of acellular dermal matrix (ADM), combined intra- or postoperative antibiotic use, surgical plane, insertion with concurrent mastectomy procedure, nipple sparing, operation type (direct to implant or 2-stage insertion), and indication for surgery. Patient-level procedure laterality is also reported.

PROMs

Following successful feasibility and pilot studies,12,18 the ABDR administers the BREAST-Q IS module to breast implant recipients at 1, 2, and 5 years following insertion of a breast device (survey methods have been published previously).19 This module comprises 5 questions relating to breast satisfaction and physical well-being. For the 3 satisfaction questions, patients are asked to rate their satisfaction with implant look, feel, and rippling on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “Very satisfied” to “Very dissatisfied.” For the 2 physical well-being questions, patients reported the frequency of implant-related pain and tightness they experience on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “None of the time” to “All of the time.”

In our analyses, each PROM question scale was categorized into a binary variable. The questions relating to satisfaction have been dichotomized to “Satisfied” and “Dissatisfied” by combining the “Very” and “Somewhat” categories for each. The physical well-being question scale has been dichotomized to a symptom frequency of “All, most, or some of the time” and “Little or none of the time.” These scales were dichotomized because initial analysis of the data revealed floor/ceiling effects in terms of patients’ responses as well as low frequencies in some categories (Table 1).

Implant-Level PROMs at 1-Year Follow-Up for All Primary Implants and by Procedure Indication

| . | All primary implants . | Reconstructive primary implants . | Aesthetic primary implants . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 14,266 | 2221 | 12,045 |

| Look | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 423 [3.0] | 172 [7.7] | 251 [2.1] |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 1184 [8.3] | 405 [18.2] | 779 [6.5] |

| Somewhat satisfied | 4220 [29.6] | 928 [41.8] | 3292 [27.3] |

| Very satisfied | 8439 [59.2] | 716 [32.2] | 7723 [64.1] |

| Feel | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 311 [2.2] | 140 [6.3] | 171 [1.4] |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 1004 [7.0] | 371 [16.7] | 633 [5.3] |

| Somewhat satisfied | 4296 [30.1] | 993 [44.7] | 3303 [27.4] |

| Very satisfied | 8655 [60.7] | 717 [32.3] | 7938 [65.9] |

| Rippling | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 372 [2.6] | 150 [6.8] | 222 [1.8] |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 1042 [7.3] | 382 [17.2] | 660 [5.5] |

| Somewhat satisfied | 2136 [15.0] | 633 [28.5] | 1503 [12.5] |

| Very satisfied | 10,716 [75.1] | 1056 [47.5] | 9660 [80.2] |

| Pain | |||

| All of the time | 92 [0.6] | 30 [1.4] | 62 [0.5] |

| Most of the time | 353 [2.5] | 111 [5.0] | 242 [2.0] |

| Some of the time | 1554 [10.9] | 406 [18.3] | 1148 [9.5] |

| A little of the time | 3850 [27.0] | 600 [27.0] | 3250 [27.0] |

| None of the time | 8417 [59.0] | 1074 [48.4] | 7343 [61.0] |

| Tightness | |||

| All of the time | 218 [1.5] | 148 [6.7] | 70 [0.6] |

| Most of the time | 420 [2.9] | 251 [11.3] | 169 [1.4] |

| Some of the time | 936 [6.6] | 337 [15.2] | 599 [5.0] |

| A little of the time | 2333 [16.4] | 531 [23.9] | 1802 [15.0] |

| None of the time | 10,359 [72.6] | 954 [43.0] | 9405 [78.1] |

| . | All primary implants . | Reconstructive primary implants . | Aesthetic primary implants . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 14,266 | 2221 | 12,045 |

| Look | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 423 [3.0] | 172 [7.7] | 251 [2.1] |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 1184 [8.3] | 405 [18.2] | 779 [6.5] |

| Somewhat satisfied | 4220 [29.6] | 928 [41.8] | 3292 [27.3] |

| Very satisfied | 8439 [59.2] | 716 [32.2] | 7723 [64.1] |

| Feel | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 311 [2.2] | 140 [6.3] | 171 [1.4] |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 1004 [7.0] | 371 [16.7] | 633 [5.3] |

| Somewhat satisfied | 4296 [30.1] | 993 [44.7] | 3303 [27.4] |

| Very satisfied | 8655 [60.7] | 717 [32.3] | 7938 [65.9] |

| Rippling | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 372 [2.6] | 150 [6.8] | 222 [1.8] |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 1042 [7.3] | 382 [17.2] | 660 [5.5] |

| Somewhat satisfied | 2136 [15.0] | 633 [28.5] | 1503 [12.5] |

| Very satisfied | 10,716 [75.1] | 1056 [47.5] | 9660 [80.2] |

| Pain | |||

| All of the time | 92 [0.6] | 30 [1.4] | 62 [0.5] |

| Most of the time | 353 [2.5] | 111 [5.0] | 242 [2.0] |

| Some of the time | 1554 [10.9] | 406 [18.3] | 1148 [9.5] |

| A little of the time | 3850 [27.0] | 600 [27.0] | 3250 [27.0] |

| None of the time | 8417 [59.0] | 1074 [48.4] | 7343 [61.0] |

| Tightness | |||

| All of the time | 218 [1.5] | 148 [6.7] | 70 [0.6] |

| Most of the time | 420 [2.9] | 251 [11.3] | 169 [1.4] |

| Some of the time | 936 [6.6] | 337 [15.2] | 599 [5.0] |

| A little of the time | 2333 [16.4] | 531 [23.9] | 1802 [15.0] |

| None of the time | 10,359 [72.6] | 954 [43.0] | 9405 [78.1] |

Values are n [%].

Implant-Level PROMs at 1-Year Follow-Up for All Primary Implants and by Procedure Indication

| . | All primary implants . | Reconstructive primary implants . | Aesthetic primary implants . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 14,266 | 2221 | 12,045 |

| Look | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 423 [3.0] | 172 [7.7] | 251 [2.1] |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 1184 [8.3] | 405 [18.2] | 779 [6.5] |

| Somewhat satisfied | 4220 [29.6] | 928 [41.8] | 3292 [27.3] |

| Very satisfied | 8439 [59.2] | 716 [32.2] | 7723 [64.1] |

| Feel | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 311 [2.2] | 140 [6.3] | 171 [1.4] |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 1004 [7.0] | 371 [16.7] | 633 [5.3] |

| Somewhat satisfied | 4296 [30.1] | 993 [44.7] | 3303 [27.4] |

| Very satisfied | 8655 [60.7] | 717 [32.3] | 7938 [65.9] |

| Rippling | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 372 [2.6] | 150 [6.8] | 222 [1.8] |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 1042 [7.3] | 382 [17.2] | 660 [5.5] |

| Somewhat satisfied | 2136 [15.0] | 633 [28.5] | 1503 [12.5] |

| Very satisfied | 10,716 [75.1] | 1056 [47.5] | 9660 [80.2] |

| Pain | |||

| All of the time | 92 [0.6] | 30 [1.4] | 62 [0.5] |

| Most of the time | 353 [2.5] | 111 [5.0] | 242 [2.0] |

| Some of the time | 1554 [10.9] | 406 [18.3] | 1148 [9.5] |

| A little of the time | 3850 [27.0] | 600 [27.0] | 3250 [27.0] |

| None of the time | 8417 [59.0] | 1074 [48.4] | 7343 [61.0] |

| Tightness | |||

| All of the time | 218 [1.5] | 148 [6.7] | 70 [0.6] |

| Most of the time | 420 [2.9] | 251 [11.3] | 169 [1.4] |

| Some of the time | 936 [6.6] | 337 [15.2] | 599 [5.0] |

| A little of the time | 2333 [16.4] | 531 [23.9] | 1802 [15.0] |

| None of the time | 10,359 [72.6] | 954 [43.0] | 9405 [78.1] |

| . | All primary implants . | Reconstructive primary implants . | Aesthetic primary implants . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 14,266 | 2221 | 12,045 |

| Look | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 423 [3.0] | 172 [7.7] | 251 [2.1] |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 1184 [8.3] | 405 [18.2] | 779 [6.5] |

| Somewhat satisfied | 4220 [29.6] | 928 [41.8] | 3292 [27.3] |

| Very satisfied | 8439 [59.2] | 716 [32.2] | 7723 [64.1] |

| Feel | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 311 [2.2] | 140 [6.3] | 171 [1.4] |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 1004 [7.0] | 371 [16.7] | 633 [5.3] |

| Somewhat satisfied | 4296 [30.1] | 993 [44.7] | 3303 [27.4] |

| Very satisfied | 8655 [60.7] | 717 [32.3] | 7938 [65.9] |

| Rippling | |||

| Very dissatisfied | 372 [2.6] | 150 [6.8] | 222 [1.8] |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 1042 [7.3] | 382 [17.2] | 660 [5.5] |

| Somewhat satisfied | 2136 [15.0] | 633 [28.5] | 1503 [12.5] |

| Very satisfied | 10,716 [75.1] | 1056 [47.5] | 9660 [80.2] |

| Pain | |||

| All of the time | 92 [0.6] | 30 [1.4] | 62 [0.5] |

| Most of the time | 353 [2.5] | 111 [5.0] | 242 [2.0] |

| Some of the time | 1554 [10.9] | 406 [18.3] | 1148 [9.5] |

| A little of the time | 3850 [27.0] | 600 [27.0] | 3250 [27.0] |

| None of the time | 8417 [59.0] | 1074 [48.4] | 7343 [61.0] |

| Tightness | |||

| All of the time | 218 [1.5] | 148 [6.7] | 70 [0.6] |

| Most of the time | 420 [2.9] | 251 [11.3] | 169 [1.4] |

| Some of the time | 936 [6.6] | 337 [15.2] | 599 [5.0] |

| A little of the time | 2333 [16.4] | 531 [23.9] | 1802 [15.0] |

| None of the time | 10,359 [72.6] | 954 [43.0] | 9405 [78.1] |

Values are n [%].

Statistical Methods

All analyses were conducted separately for reconstructive and aesthetic implant cohorts. Demographic and clinical characteristics relating to the device insertion procedures were summarized with descriptive statistics. Logistic regression was used to assess the association between primary breast device PROMs and relevant demographic and clinical characteristics. The standard errors for the models were adjusted for repeated observations from the same patient. The investigated factors were determined a priori by clinicians (Supplemental Table 1, available online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were presented as measures of effect size. We considered linear and categoric formulations for age according to the Akaike information criterion (Supplemental Table 2, available online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com). Missing data for categoric variables were kept as a separate category in the models.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted for each of the 5 patient outcomes. Starting with the most significant variable identified in the univariate model, we sequentially added the next most significant covariate and used the Wald test to determine whether they significantly improved model fit. This was done sequentially until all the variables were evaluated.

Analyses was conducted in Stata/IC version 16 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX) with the level of significance set at 5%. Low-risk ethics approval was obtained from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID 27535), an IRB equivalent.

RESULTS

A total of 2221 reconstructive and 12,045 aesthetic primary breast implant insertion procedures were included in the study (Figure 1), from a total of 1358 reconstruction and 6035 cosmetic augmentation patients with a mean age of 48.3 years (range, 16.5-82.0 years) and 33.4 years (range, 17.4-78.0 years), respectively. Of the included patients, 1358 (100%) reconstruction patients and 6033 (>99.9%) cosmetic augmentation patients were female; 1 (<0.1%) cosmetic augmentation patient was male. The demographic and clinical characteristics of each procedure cohort are summarized in Table 2. Median age at operation was 47.8 years (interquartile range, 38.8-55.5 years) for the reconstructive cohort and 32.3 years (interquartile range, 25.7-39.1) for the aesthetic cohort.

Demographic and Clinical Overview of Reconstructive and Aesthetic Breast Implant Cohorts

| . | Reconstructive . | Aesthetic . |

|---|---|---|

| N | 2221 | 12,045 |

| Age at operation | ||

| Mean [SD] | 47.2 [12.7] | 33.4 [9.4] |

| Median (IQR) | 47.8 (38.8-55.5) | 32.3 (25.7-39.1) |

| Age (years) | ||

| <30 | 212 [9.5] | 4894 [40.6] |

| 30-39 | 407 [18.3] | 4492 [37.3] |

| 40-49 | 642 [28.9] | 1948 [16.2] |

| 50-59 | 602 [27.1] | 609 [5.1] |

| ≥60 | 358 [16.1] | 102 [0.8] |

| Site type | ||

| Public hospital | 448 [20.2] | |

| Private facility | 1773 [79.8] | |

| Site state | ||

| NSW and ACT | 558 [25.1] | 3979 [33.0] |

| VIC and TAS | 604 [27.2] | 3143 [26.1] |

| QLD | 480 [21.6] | 3039 [25.2] |

| SA and NT | 287 [12.9] | 687 [5.7] |

| WA | 292 [13.1] | 1197 [9.9] |

| Operation year | ||

| 2016 | 73 [3.3] | 237 [2.0] |

| 2017 | 645 [29.0] | 4705 [39.1] |

| 2018 | 1503 [67.7] | 7103 [59.0] |

| Previous radiation therapy | ||

| No | 1762 [79.3] | |

| Yes | 272 [12.2] | |

| Not stated | 187 [8.4] | |

| Acellular dermal matrix use | ||

| No | 1759 [79.2] | 11,965 [99.3] |

| Yes | 437 [19.7] | 2 [<1] |

| Not stated | 25 [1.1] | 78 [0.6] |

| Intra-/postoperative antibiotic use | ||

| No | 33 [1.5] | 453 [3.8] |

| Yes | 1962 [88.3] | 11,111 [92.2] |

| Not stated | 226 [10.2] | 481 [4.0] |

| Surgical plane | ||

| Subglandular/subfascial | 163 [7.3] | 1243 [10.3] |

| Subpectoral/dual plane | 1452 [65.4] | 10,008 [83.1] |

| Subflap | 189 [8.5] | 12 [0.1] |

| Other | 47 [2.1] | 8 [0.1] |

| Not stated | 370 [16.7] | 774 [6.4] |

| Concurrent mastectomy | ||

| No | 1537 [69.2] | |

| Yes | 585 [26.3] | |

| Not stated | 99 [4.5] | |

| Patient level procedure type | ||

| Unilateral | 493 [22.2] | 8 [0.1] |

| Bilateral | 1728 [77.8] | 12,037 [99.9] |

| Nipple sparing | ||

| No | 1665 [75.0] | |

| Yes | 556 [25.0] | |

| Operation indication | ||

| Post-cancer | 1384 [62.3] | |

| Risk reduction | 645 [29.0] | |

| Developmental deformity | 192 [8.6] | |

| Operation type | ||

| Direct to implant | 964 [43.4] | |

| Two-stage implant | 1257 [56.6] |

| . | Reconstructive . | Aesthetic . |

|---|---|---|

| N | 2221 | 12,045 |

| Age at operation | ||

| Mean [SD] | 47.2 [12.7] | 33.4 [9.4] |

| Median (IQR) | 47.8 (38.8-55.5) | 32.3 (25.7-39.1) |

| Age (years) | ||

| <30 | 212 [9.5] | 4894 [40.6] |

| 30-39 | 407 [18.3] | 4492 [37.3] |

| 40-49 | 642 [28.9] | 1948 [16.2] |

| 50-59 | 602 [27.1] | 609 [5.1] |

| ≥60 | 358 [16.1] | 102 [0.8] |

| Site type | ||

| Public hospital | 448 [20.2] | |

| Private facility | 1773 [79.8] | |

| Site state | ||

| NSW and ACT | 558 [25.1] | 3979 [33.0] |

| VIC and TAS | 604 [27.2] | 3143 [26.1] |

| QLD | 480 [21.6] | 3039 [25.2] |

| SA and NT | 287 [12.9] | 687 [5.7] |

| WA | 292 [13.1] | 1197 [9.9] |

| Operation year | ||

| 2016 | 73 [3.3] | 237 [2.0] |

| 2017 | 645 [29.0] | 4705 [39.1] |

| 2018 | 1503 [67.7] | 7103 [59.0] |

| Previous radiation therapy | ||

| No | 1762 [79.3] | |

| Yes | 272 [12.2] | |

| Not stated | 187 [8.4] | |

| Acellular dermal matrix use | ||

| No | 1759 [79.2] | 11,965 [99.3] |

| Yes | 437 [19.7] | 2 [<1] |

| Not stated | 25 [1.1] | 78 [0.6] |

| Intra-/postoperative antibiotic use | ||

| No | 33 [1.5] | 453 [3.8] |

| Yes | 1962 [88.3] | 11,111 [92.2] |

| Not stated | 226 [10.2] | 481 [4.0] |

| Surgical plane | ||

| Subglandular/subfascial | 163 [7.3] | 1243 [10.3] |

| Subpectoral/dual plane | 1452 [65.4] | 10,008 [83.1] |

| Subflap | 189 [8.5] | 12 [0.1] |

| Other | 47 [2.1] | 8 [0.1] |

| Not stated | 370 [16.7] | 774 [6.4] |

| Concurrent mastectomy | ||

| No | 1537 [69.2] | |

| Yes | 585 [26.3] | |

| Not stated | 99 [4.5] | |

| Patient level procedure type | ||

| Unilateral | 493 [22.2] | 8 [0.1] |

| Bilateral | 1728 [77.8] | 12,037 [99.9] |

| Nipple sparing | ||

| No | 1665 [75.0] | |

| Yes | 556 [25.0] | |

| Operation indication | ||

| Post-cancer | 1384 [62.3] | |

| Risk reduction | 645 [29.0] | |

| Developmental deformity | 192 [8.6] | |

| Operation type | ||

| Direct to implant | 964 [43.4] | |

| Two-stage implant | 1257 [56.6] |

Values are n [%] unless otherwise stated. ACT, Australian Capital Territory; IQR, interquartile range; NSW, New South Wales, NT, Northern Territory; QLD, Queensland; SA, South Australia; SD, standard deviation; TAS, Tasmania; VIC, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

Demographic and Clinical Overview of Reconstructive and Aesthetic Breast Implant Cohorts

| . | Reconstructive . | Aesthetic . |

|---|---|---|

| N | 2221 | 12,045 |

| Age at operation | ||

| Mean [SD] | 47.2 [12.7] | 33.4 [9.4] |

| Median (IQR) | 47.8 (38.8-55.5) | 32.3 (25.7-39.1) |

| Age (years) | ||

| <30 | 212 [9.5] | 4894 [40.6] |

| 30-39 | 407 [18.3] | 4492 [37.3] |

| 40-49 | 642 [28.9] | 1948 [16.2] |

| 50-59 | 602 [27.1] | 609 [5.1] |

| ≥60 | 358 [16.1] | 102 [0.8] |

| Site type | ||

| Public hospital | 448 [20.2] | |

| Private facility | 1773 [79.8] | |

| Site state | ||

| NSW and ACT | 558 [25.1] | 3979 [33.0] |

| VIC and TAS | 604 [27.2] | 3143 [26.1] |

| QLD | 480 [21.6] | 3039 [25.2] |

| SA and NT | 287 [12.9] | 687 [5.7] |

| WA | 292 [13.1] | 1197 [9.9] |

| Operation year | ||

| 2016 | 73 [3.3] | 237 [2.0] |

| 2017 | 645 [29.0] | 4705 [39.1] |

| 2018 | 1503 [67.7] | 7103 [59.0] |

| Previous radiation therapy | ||

| No | 1762 [79.3] | |

| Yes | 272 [12.2] | |

| Not stated | 187 [8.4] | |

| Acellular dermal matrix use | ||

| No | 1759 [79.2] | 11,965 [99.3] |

| Yes | 437 [19.7] | 2 [<1] |

| Not stated | 25 [1.1] | 78 [0.6] |

| Intra-/postoperative antibiotic use | ||

| No | 33 [1.5] | 453 [3.8] |

| Yes | 1962 [88.3] | 11,111 [92.2] |

| Not stated | 226 [10.2] | 481 [4.0] |

| Surgical plane | ||

| Subglandular/subfascial | 163 [7.3] | 1243 [10.3] |

| Subpectoral/dual plane | 1452 [65.4] | 10,008 [83.1] |

| Subflap | 189 [8.5] | 12 [0.1] |

| Other | 47 [2.1] | 8 [0.1] |

| Not stated | 370 [16.7] | 774 [6.4] |

| Concurrent mastectomy | ||

| No | 1537 [69.2] | |

| Yes | 585 [26.3] | |

| Not stated | 99 [4.5] | |

| Patient level procedure type | ||

| Unilateral | 493 [22.2] | 8 [0.1] |

| Bilateral | 1728 [77.8] | 12,037 [99.9] |

| Nipple sparing | ||

| No | 1665 [75.0] | |

| Yes | 556 [25.0] | |

| Operation indication | ||

| Post-cancer | 1384 [62.3] | |

| Risk reduction | 645 [29.0] | |

| Developmental deformity | 192 [8.6] | |

| Operation type | ||

| Direct to implant | 964 [43.4] | |

| Two-stage implant | 1257 [56.6] |

| . | Reconstructive . | Aesthetic . |

|---|---|---|

| N | 2221 | 12,045 |

| Age at operation | ||

| Mean [SD] | 47.2 [12.7] | 33.4 [9.4] |

| Median (IQR) | 47.8 (38.8-55.5) | 32.3 (25.7-39.1) |

| Age (years) | ||

| <30 | 212 [9.5] | 4894 [40.6] |

| 30-39 | 407 [18.3] | 4492 [37.3] |

| 40-49 | 642 [28.9] | 1948 [16.2] |

| 50-59 | 602 [27.1] | 609 [5.1] |

| ≥60 | 358 [16.1] | 102 [0.8] |

| Site type | ||

| Public hospital | 448 [20.2] | |

| Private facility | 1773 [79.8] | |

| Site state | ||

| NSW and ACT | 558 [25.1] | 3979 [33.0] |

| VIC and TAS | 604 [27.2] | 3143 [26.1] |

| QLD | 480 [21.6] | 3039 [25.2] |

| SA and NT | 287 [12.9] | 687 [5.7] |

| WA | 292 [13.1] | 1197 [9.9] |

| Operation year | ||

| 2016 | 73 [3.3] | 237 [2.0] |

| 2017 | 645 [29.0] | 4705 [39.1] |

| 2018 | 1503 [67.7] | 7103 [59.0] |

| Previous radiation therapy | ||

| No | 1762 [79.3] | |

| Yes | 272 [12.2] | |

| Not stated | 187 [8.4] | |

| Acellular dermal matrix use | ||

| No | 1759 [79.2] | 11,965 [99.3] |

| Yes | 437 [19.7] | 2 [<1] |

| Not stated | 25 [1.1] | 78 [0.6] |

| Intra-/postoperative antibiotic use | ||

| No | 33 [1.5] | 453 [3.8] |

| Yes | 1962 [88.3] | 11,111 [92.2] |

| Not stated | 226 [10.2] | 481 [4.0] |

| Surgical plane | ||

| Subglandular/subfascial | 163 [7.3] | 1243 [10.3] |

| Subpectoral/dual plane | 1452 [65.4] | 10,008 [83.1] |

| Subflap | 189 [8.5] | 12 [0.1] |

| Other | 47 [2.1] | 8 [0.1] |

| Not stated | 370 [16.7] | 774 [6.4] |

| Concurrent mastectomy | ||

| No | 1537 [69.2] | |

| Yes | 585 [26.3] | |

| Not stated | 99 [4.5] | |

| Patient level procedure type | ||

| Unilateral | 493 [22.2] | 8 [0.1] |

| Bilateral | 1728 [77.8] | 12,037 [99.9] |

| Nipple sparing | ||

| No | 1665 [75.0] | |

| Yes | 556 [25.0] | |

| Operation indication | ||

| Post-cancer | 1384 [62.3] | |

| Risk reduction | 645 [29.0] | |

| Developmental deformity | 192 [8.6] | |

| Operation type | ||

| Direct to implant | 964 [43.4] | |

| Two-stage implant | 1257 [56.6] |

Values are n [%] unless otherwise stated. ACT, Australian Capital Territory; IQR, interquartile range; NSW, New South Wales, NT, Northern Territory; QLD, Queensland; SA, South Australia; SD, standard deviation; TAS, Tasmania; VIC, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

Private facilities were the most common location for reconstruction procedures, with 80% of reconstructive procedures occurring in a private hospital and 20% in a public hospital; only aesthetic implants inserted in a private facility were eligible for inclusion in the study (16 aesthetic implants recorded as occurring in public hospitals were excluded due to concerns about misclassification). For reconstructive insertions, post-cancer was the most common indication for operation (62%), followed by risk reduction (29%) and developmental deformity (9%). For breast reconstruction, 26% of procedures were performed concurrently with a mastectomy, 22% were unilateral, 25% were nipple sparing, 12% were in previously irradiated breasts, and 20% involved the use of ADM/mesh. A tissue expander to implant exchange procedure, reflecting a 2-stage reconstruction, was used for 57% of reconstructive implants. Over 99% of aesthetic procedures were bilateral at the patient level and less than 1% involved the use of ADM.

The results of the univariate logistic regression between patient and surgical characteristics and PROMs for the reconstructive cohort are presented in Supplemental Tables 3-7 (available online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com). The univariate associations differed for each PROM, with only operation indication being significantly associated with all PROMs. Significant factors in the univariate models for the implant look satisfaction PROM were age, site type, operation year, indication for operation (post-cancer, risk reduction, developmental deformity), and insertion operation type (direct to implant or 2-stage insertion). Operation year and operation indication were associated with satisfaction with feel; age, site type, site state, operation year, ADM use, nipple sparing, insertion during concurrent mastectomy, and operation indication were associated with rippling. For the implant experience PROMs, age, site type, and operation indication were associated with pain frequency, and age, previous radiation therapy, intra- or postoperative antibiotic use, surgical plane, patient-level procedure laterality, operation indication, and operation type were associated with implant tightness. Univariate results for the aesthetic implant cohort are presented in Supplemental Tables 8-12 (available online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com); no univariate factor was significantly associated with all PROMs, although age at operation was the most significant factor associated with 4 of the 5 outcomes (look, rippling, pain, and tightness). Surgical plane of insertion was the most significant factor in the univariate analysis for aesthetic implant feel.

As with the univariate associations, factors included in the multivariate models differed within and between the indication cohorts by each PROM. Figure 2 and Table 3 present the final multivariate models and 1-year follow-up PROM associations for the primary reconstructive implant insertion procedures. Operation indication was included in all 5 PROM models; implants inserted for a developmental deformity indication had significantly lower dissatisfaction and symptom frequency compared with post-cancer implants, with ORs ranging from 0.40 (95% CI, 0.19-0.83) for tightness to 0.10 (95% CI, 0.03-0.39) for rippling. In addition, implants for risk-reducing reconstructions were also associated with 0.74 (95% CI, 0.58-0.94) times the odds of tightness all, most, or some of the time compared with post-cancer reconstructions.

Final Multivariate Models for the BREAST-Q Implant Surveillance Individual Questions at 1-Year Follow-Up for Primary Reconstructive Implants (N = 2221)

| . | Odds ratio . | 95% CI . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Look dissatisfaction | |||

| Site type | |||

| Public hospital | 1.82 | 1.36-2.44 | <0.001 |

| Private facility | Reference | ||

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.88 | 0.69-1.12 | 0.296 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.34 | 0.19-0.61 | <0.001 |

| Concurrent mastectomy | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.70 | 0.52-0.94 | 0.017 |

| Not stated | 1.09 | 0.62-1.92 | 0.767 |

| Feel dissatisfaction | |||

| Operation year | |||

| 2016 | 0.87 | 0.43-1.75 | 0.690 |

| 2017 | 0.64 | 0.47-0.87 | 0.005 |

| 2018 | Reference | ||

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.80 | 0.62-1.02 | 0.071 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.34 | 0.18-0.64 | 0.001 |

| Rippling dissatisfaction | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 2.49 | 1.14-5.45 | 0.022 |

| 40-49 | 2.31 | 1.07-4.97 | 0.033 |

| 50-59 | 1.98 | 0.91-4.28 | 0.085 |

| ≥60 | 1.53 | 0.68-3.43 | 0.302 |

| Site type | |||

| Public hospital | 1.46 | 1.08-1.98 | 0.013 |

| Private facility | Reference | ||

| Nipple sparing | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.52 | 1.15-2.03 | 0.004 |

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 1.15 | 0.90-1.47 | 0.263 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.10 | 0.03-0.39 | 0.001 |

| Pain all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Site type | |||

| Public hospital | 1.62 | 1.21-2.18 | 0.001 |

| Private facility | Reference | ||

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.82 | 0.65-1.04 | 0.105 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.38 | 0.21-0.71 | 0.002 |

| Tightness all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 1.29 | 0.64-2.61 | 0.478 |

| 40-49 | 1.94 | 0.97-3.85 | 0.060 |

| 50-59 | 2.93 | 1.46-5.85 | 0.002 |

| ≥60 | 1.95 | 0.96-3.98 | 0.066 |

| Previous radiation therapy | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.71 | 1.26-2.32 | 0.001 |

| Not stated | 1.23 | 0.81-1.87 | 0.328 |

| Intra/postoperative antibiotic use | |||

| No | 0.66 | 0.25-1.74 | 0.396 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Not stated | 1.84 | 1.27-2.68 | 0.001 |

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.74 | 0.58-0.94 | 0.014 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.40 | 0.19-0.83 | 0.014 |

| . | Odds ratio . | 95% CI . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Look dissatisfaction | |||

| Site type | |||

| Public hospital | 1.82 | 1.36-2.44 | <0.001 |

| Private facility | Reference | ||

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.88 | 0.69-1.12 | 0.296 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.34 | 0.19-0.61 | <0.001 |

| Concurrent mastectomy | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.70 | 0.52-0.94 | 0.017 |

| Not stated | 1.09 | 0.62-1.92 | 0.767 |

| Feel dissatisfaction | |||

| Operation year | |||

| 2016 | 0.87 | 0.43-1.75 | 0.690 |

| 2017 | 0.64 | 0.47-0.87 | 0.005 |

| 2018 | Reference | ||

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.80 | 0.62-1.02 | 0.071 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.34 | 0.18-0.64 | 0.001 |

| Rippling dissatisfaction | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 2.49 | 1.14-5.45 | 0.022 |

| 40-49 | 2.31 | 1.07-4.97 | 0.033 |

| 50-59 | 1.98 | 0.91-4.28 | 0.085 |

| ≥60 | 1.53 | 0.68-3.43 | 0.302 |

| Site type | |||

| Public hospital | 1.46 | 1.08-1.98 | 0.013 |

| Private facility | Reference | ||

| Nipple sparing | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.52 | 1.15-2.03 | 0.004 |

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 1.15 | 0.90-1.47 | 0.263 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.10 | 0.03-0.39 | 0.001 |

| Pain all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Site type | |||

| Public hospital | 1.62 | 1.21-2.18 | 0.001 |

| Private facility | Reference | ||

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.82 | 0.65-1.04 | 0.105 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.38 | 0.21-0.71 | 0.002 |

| Tightness all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 1.29 | 0.64-2.61 | 0.478 |

| 40-49 | 1.94 | 0.97-3.85 | 0.060 |

| 50-59 | 2.93 | 1.46-5.85 | 0.002 |

| ≥60 | 1.95 | 0.96-3.98 | 0.066 |

| Previous radiation therapy | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.71 | 1.26-2.32 | 0.001 |

| Not stated | 1.23 | 0.81-1.87 | 0.328 |

| Intra/postoperative antibiotic use | |||

| No | 0.66 | 0.25-1.74 | 0.396 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Not stated | 1.84 | 1.27-2.68 | 0.001 |

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.74 | 0.58-0.94 | 0.014 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.40 | 0.19-0.83 | 0.014 |

Final Multivariate Models for the BREAST-Q Implant Surveillance Individual Questions at 1-Year Follow-Up for Primary Reconstructive Implants (N = 2221)

| . | Odds ratio . | 95% CI . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Look dissatisfaction | |||

| Site type | |||

| Public hospital | 1.82 | 1.36-2.44 | <0.001 |

| Private facility | Reference | ||

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.88 | 0.69-1.12 | 0.296 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.34 | 0.19-0.61 | <0.001 |

| Concurrent mastectomy | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.70 | 0.52-0.94 | 0.017 |

| Not stated | 1.09 | 0.62-1.92 | 0.767 |

| Feel dissatisfaction | |||

| Operation year | |||

| 2016 | 0.87 | 0.43-1.75 | 0.690 |

| 2017 | 0.64 | 0.47-0.87 | 0.005 |

| 2018 | Reference | ||

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.80 | 0.62-1.02 | 0.071 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.34 | 0.18-0.64 | 0.001 |

| Rippling dissatisfaction | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 2.49 | 1.14-5.45 | 0.022 |

| 40-49 | 2.31 | 1.07-4.97 | 0.033 |

| 50-59 | 1.98 | 0.91-4.28 | 0.085 |

| ≥60 | 1.53 | 0.68-3.43 | 0.302 |

| Site type | |||

| Public hospital | 1.46 | 1.08-1.98 | 0.013 |

| Private facility | Reference | ||

| Nipple sparing | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.52 | 1.15-2.03 | 0.004 |

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 1.15 | 0.90-1.47 | 0.263 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.10 | 0.03-0.39 | 0.001 |

| Pain all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Site type | |||

| Public hospital | 1.62 | 1.21-2.18 | 0.001 |

| Private facility | Reference | ||

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.82 | 0.65-1.04 | 0.105 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.38 | 0.21-0.71 | 0.002 |

| Tightness all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 1.29 | 0.64-2.61 | 0.478 |

| 40-49 | 1.94 | 0.97-3.85 | 0.060 |

| 50-59 | 2.93 | 1.46-5.85 | 0.002 |

| ≥60 | 1.95 | 0.96-3.98 | 0.066 |

| Previous radiation therapy | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.71 | 1.26-2.32 | 0.001 |

| Not stated | 1.23 | 0.81-1.87 | 0.328 |

| Intra/postoperative antibiotic use | |||

| No | 0.66 | 0.25-1.74 | 0.396 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Not stated | 1.84 | 1.27-2.68 | 0.001 |

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.74 | 0.58-0.94 | 0.014 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.40 | 0.19-0.83 | 0.014 |

| . | Odds ratio . | 95% CI . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Look dissatisfaction | |||

| Site type | |||

| Public hospital | 1.82 | 1.36-2.44 | <0.001 |

| Private facility | Reference | ||

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.88 | 0.69-1.12 | 0.296 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.34 | 0.19-0.61 | <0.001 |

| Concurrent mastectomy | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.70 | 0.52-0.94 | 0.017 |

| Not stated | 1.09 | 0.62-1.92 | 0.767 |

| Feel dissatisfaction | |||

| Operation year | |||

| 2016 | 0.87 | 0.43-1.75 | 0.690 |

| 2017 | 0.64 | 0.47-0.87 | 0.005 |

| 2018 | Reference | ||

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.80 | 0.62-1.02 | 0.071 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.34 | 0.18-0.64 | 0.001 |

| Rippling dissatisfaction | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 2.49 | 1.14-5.45 | 0.022 |

| 40-49 | 2.31 | 1.07-4.97 | 0.033 |

| 50-59 | 1.98 | 0.91-4.28 | 0.085 |

| ≥60 | 1.53 | 0.68-3.43 | 0.302 |

| Site type | |||

| Public hospital | 1.46 | 1.08-1.98 | 0.013 |

| Private facility | Reference | ||

| Nipple sparing | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.52 | 1.15-2.03 | 0.004 |

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 1.15 | 0.90-1.47 | 0.263 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.10 | 0.03-0.39 | 0.001 |

| Pain all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Site type | |||

| Public hospital | 1.62 | 1.21-2.18 | 0.001 |

| Private facility | Reference | ||

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.82 | 0.65-1.04 | 0.105 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.38 | 0.21-0.71 | 0.002 |

| Tightness all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 1.29 | 0.64-2.61 | 0.478 |

| 40-49 | 1.94 | 0.97-3.85 | 0.060 |

| 50-59 | 2.93 | 1.46-5.85 | 0.002 |

| ≥60 | 1.95 | 0.96-3.98 | 0.066 |

| Previous radiation therapy | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.71 | 1.26-2.32 | 0.001 |

| Not stated | 1.23 | 0.81-1.87 | 0.328 |

| Intra/postoperative antibiotic use | |||

| No | 0.66 | 0.25-1.74 | 0.396 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Not stated | 1.84 | 1.27-2.68 | 0.001 |

| Operation indication | |||

| Post-cancer | Reference | ||

| Risk reduction | 0.74 | 0.58-0.94 | 0.014 |

| Developmental deformity | 0.40 | 0.19-0.83 | 0.014 |

Forest plot showing the odds ratios and 95% CIs for the final multivariate BREAST-Q implant surveillance questions at 1-year follow-up for primary reconstructive implants.

Site type was included in 3 of the final models; reconstructive implant insertions in a public hospital, compared to private facilities, had lower satisfaction with look (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.36-2.44) and rippling (OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.08-1.98) and higher pain frequency (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.21-2.18). Patient age at operation was included in 2 final models. Compared to age <30 years, implants for patients aged 30 to 39 and 40 to 49 years were associated with significantly higher rippling dissatisfaction with ORs of 2.49 (95% CI, 1.14-5.45) and 2.31 (95% CI, 1.07-4.97), respectively. Significantly worse tightness was found for patients aged 50 to 59 years (OR, 2.93; 95% CI, 1.46-5.85) than for patients aged <30 years. Concurrent mastectomy, year of operation, previous radiation therapy, intra- or postoperative antibiotic use, and nipple-sparing insertion were each included in 1 final reconstructive multivariate model. Primary implants for reconstruction inserted with a concurrent mastectomy were associated with higher look satisfaction (OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.52-0.94) than implants not inserted with concurrent mastectomy. Implants inserted in 2017 compared to 2018 had higher feel satisfaction (OR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.47-0.87). Nipple-sparing procedures had higher rippling dissatisfaction (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.15-2.03) than procedures without. Previous radiation therapy (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.26-2.32) and “Not stated” antibiotic use (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.27-2.68), compared with no previous and antibiotic use, respectively, were both associated with higher implant tightness frequency at 1-year follow-up.

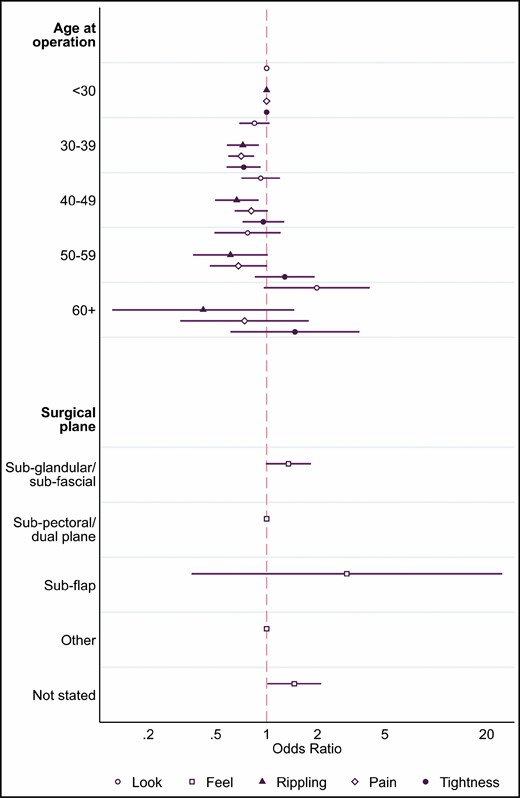

The final models and logistic regression results are shown in Figure 3 and Table 4. Age at operation was included in 4 of the 5 PROM final models. Compared with patients aged <30 years, patients aged 30 to 39 years receiving implants had more look (OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.69-1.04) and rippling (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.58-0.90) satisfaction and lower frequency of pain (OR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.59-0.84) and tightness (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.58-0.92). Implants for patients aged 40 to 49 years were also associated with significantly higher rippling satisfaction (OR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.49-0.90). Surgical plane was the only factor included in the final model for the breast feel PROM. Compared with primary aesthetic implants inserted in the subpectoral or dual plane, implants inserted in the subglandular or subfascial plane or with a “Not stated” surgical plane had higher feel dissatisfaction (OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 0.99-1.83 and OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.01-2.10, respectively).

Final Multivariate Models for the BREAST-Q Implant Surveillance Individual Questions at 1-Year Follow-Up for Aesthetic Implants (N = 12,045)

| . | Odds ratio . | 95% CI . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Look dissatisfaction | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.85 | 0.69-1.04 | 0.114 |

| 40-49 | 0.92 | 0.71-1.20 | 0.546 |

| 50-59 | 0.77 | 0.49-1.21 | 0.258 |

| ≥60 | 1.98 | 0.96-4.07 | 0.064 |

| Feel dissatisfaction | |||

| Surgical plane | |||

| Subglandular/subfascial | 1.34 | 0.99-1.83 | 0.058 |

| Subpectoral/dual plane | Reference | ||

| Subflap | 2.98 | 0.36-24.66 | 0.312 |

| Other | Omitteda | ||

| Not stated | 1.46 | 1.01-2.10 | 0.044 |

| Rippling dissatisfaction | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.72 | 0.58-0.90 | 0.004 |

| 40-49 | 0.67 | 0.49-0.90 | 0.007 |

| 50-59 | 0.61 | 0.37-1.02 | 0.057 |

| ≥60 | 0.42 | 0.12-1.46 | 0.172 |

| Pain all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.71 | 0.59-0.84 | <0.001 |

| 40-49 | 0.81 | 0.65-1.02 | 0.070 |

| 50-59 | 0.68 | 0.46-1.01 | 0.054 |

| ≥60 | 0.74 | 0.31-1.77 | 0.500 |

| Tightness all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.73 | 0.58-0.92 | 0.008 |

| 40-49 | 0.96 | 0.72-1.27 | 0.755 |

| 50-59 | 1.28 | 0.85-1.92 | 0.236 |

| ≥60 | 1.47 | 0.61-3.54 | 0.391 |

| . | Odds ratio . | 95% CI . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Look dissatisfaction | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.85 | 0.69-1.04 | 0.114 |

| 40-49 | 0.92 | 0.71-1.20 | 0.546 |

| 50-59 | 0.77 | 0.49-1.21 | 0.258 |

| ≥60 | 1.98 | 0.96-4.07 | 0.064 |

| Feel dissatisfaction | |||

| Surgical plane | |||

| Subglandular/subfascial | 1.34 | 0.99-1.83 | 0.058 |

| Subpectoral/dual plane | Reference | ||

| Subflap | 2.98 | 0.36-24.66 | 0.312 |

| Other | Omitteda | ||

| Not stated | 1.46 | 1.01-2.10 | 0.044 |

| Rippling dissatisfaction | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.72 | 0.58-0.90 | 0.004 |

| 40-49 | 0.67 | 0.49-0.90 | 0.007 |

| 50-59 | 0.61 | 0.37-1.02 | 0.057 |

| ≥60 | 0.42 | 0.12-1.46 | 0.172 |

| Pain all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.71 | 0.59-0.84 | <0.001 |

| 40-49 | 0.81 | 0.65-1.02 | 0.070 |

| 50-59 | 0.68 | 0.46-1.01 | 0.054 |

| ≥60 | 0.74 | 0.31-1.77 | 0.500 |

| Tightness all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.73 | 0.58-0.92 | 0.008 |

| 40-49 | 0.96 | 0.72-1.27 | 0.755 |

| 50-59 | 1.28 | 0.85-1.92 | 0.236 |

| ≥60 | 1.47 | 0.61-3.54 | 0.391 |

aNone of the patients with the 8 other surgical plane implants were dissatisfied with feel; due to the empty cells this category was omitted from the model (N = 12,037).

Final Multivariate Models for the BREAST-Q Implant Surveillance Individual Questions at 1-Year Follow-Up for Aesthetic Implants (N = 12,045)

| . | Odds ratio . | 95% CI . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Look dissatisfaction | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.85 | 0.69-1.04 | 0.114 |

| 40-49 | 0.92 | 0.71-1.20 | 0.546 |

| 50-59 | 0.77 | 0.49-1.21 | 0.258 |

| ≥60 | 1.98 | 0.96-4.07 | 0.064 |

| Feel dissatisfaction | |||

| Surgical plane | |||

| Subglandular/subfascial | 1.34 | 0.99-1.83 | 0.058 |

| Subpectoral/dual plane | Reference | ||

| Subflap | 2.98 | 0.36-24.66 | 0.312 |

| Other | Omitteda | ||

| Not stated | 1.46 | 1.01-2.10 | 0.044 |

| Rippling dissatisfaction | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.72 | 0.58-0.90 | 0.004 |

| 40-49 | 0.67 | 0.49-0.90 | 0.007 |

| 50-59 | 0.61 | 0.37-1.02 | 0.057 |

| ≥60 | 0.42 | 0.12-1.46 | 0.172 |

| Pain all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.71 | 0.59-0.84 | <0.001 |

| 40-49 | 0.81 | 0.65-1.02 | 0.070 |

| 50-59 | 0.68 | 0.46-1.01 | 0.054 |

| ≥60 | 0.74 | 0.31-1.77 | 0.500 |

| Tightness all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.73 | 0.58-0.92 | 0.008 |

| 40-49 | 0.96 | 0.72-1.27 | 0.755 |

| 50-59 | 1.28 | 0.85-1.92 | 0.236 |

| ≥60 | 1.47 | 0.61-3.54 | 0.391 |

| . | Odds ratio . | 95% CI . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Look dissatisfaction | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.85 | 0.69-1.04 | 0.114 |

| 40-49 | 0.92 | 0.71-1.20 | 0.546 |

| 50-59 | 0.77 | 0.49-1.21 | 0.258 |

| ≥60 | 1.98 | 0.96-4.07 | 0.064 |

| Feel dissatisfaction | |||

| Surgical plane | |||

| Subglandular/subfascial | 1.34 | 0.99-1.83 | 0.058 |

| Subpectoral/dual plane | Reference | ||

| Subflap | 2.98 | 0.36-24.66 | 0.312 |

| Other | Omitteda | ||

| Not stated | 1.46 | 1.01-2.10 | 0.044 |

| Rippling dissatisfaction | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.72 | 0.58-0.90 | 0.004 |

| 40-49 | 0.67 | 0.49-0.90 | 0.007 |

| 50-59 | 0.61 | 0.37-1.02 | 0.057 |

| ≥60 | 0.42 | 0.12-1.46 | 0.172 |

| Pain all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.71 | 0.59-0.84 | <0.001 |

| 40-49 | 0.81 | 0.65-1.02 | 0.070 |

| 50-59 | 0.68 | 0.46-1.01 | 0.054 |

| ≥60 | 0.74 | 0.31-1.77 | 0.500 |

| Tightness all, most, or some of the time | |||

| Age at operation (years) | |||

| <30 | Reference | ||

| 30-39 | 0.73 | 0.58-0.92 | 0.008 |

| 40-49 | 0.96 | 0.72-1.27 | 0.755 |

| 50-59 | 1.28 | 0.85-1.92 | 0.236 |

| ≥60 | 1.47 | 0.61-3.54 | 0.391 |

aNone of the patients with the 8 other surgical plane implants were dissatisfied with feel; due to the empty cells this category was omitted from the model (N = 12,037).

Forest plot showing the odds ratios and 95% CIs for the final BREAST-Q implant surveillance questions at 1-year follow-up for primary aesthetic implants.

Discussion

The monitoring and benchmarking of PROs following breast device surgery is a novel and evolving method of assessing device safety tracking and performance monitoring. These PROs can be impacted by many external factors, including patient demographic and clinical characteristics. As such, appropriate risk adjustment of benchmarking activities is necessary to ensure that PROs can be compared fairly. We would like to clarify that the purpose of this paper is not for patient risk prognostication or risk stratification, which serves a different clinical purpose.

This study developed models for the 5 outcomes assessed in the BREAST-Q IS tool at 1 year following breast implant insertion, stratified by procedure indication cohort, for the purpose of PROM benchmarking. In the reconstructive cohort, indication for operation (post-cancer, risk reducing, or developmental deformity) was an important factor to include in risk adjustment of PROM results, with an indication of developmental deformity having higher satisfaction and lower physical symptom frequency compared with post-cancer. Site type was also a common factor in the reconstructive cohort final models; implants inserted in public hospitals were associated with lower breast satisfaction and higher symptom frequency than implants inserted in private facilities. For aesthetic implants, age was an important factor for PROM risk adjustment.

As a newly developed PROM tool, no other studies to date have investigated factors associated with the BREAST-Q IS module for any purpose, including risk adjustment for benchmarking. The 5 questions of the BREAST-Q IS have been taken from the broader breast satisfaction (look, feel, and rippling) and physical well-being (pain and tightness) scales, which many studies have evaluated as an outcome measure following breast surgery.9 Most studies using the BREAST-Q and other PROMs following breast implant insertions have been conducted in reconstructive cohorts of breast cancer patients,10 with many comparing pre- vs postoperative scores, limiting the relevance to our results. Very few studies have assessed PROMs after cosmetic augmentation.11

In addition to endorsing PROMs for use as a surgical clinical quality indicator in breast device registries, ICOBRA also reached a consensus on 9 risk-adjustment factors to be considered for global benchmarking.14 The ABDR collects information relating to 4 of these: indication for surgery, age, ADM, and radiation therapy. All 4 available factors were evaluated for inclusion in the risk-adjustment models developed in this study. The model development was conducted stratified by indication to account for the distinct surgical pathways of reconstruction and aesthetic breast device surgeries. Indication for operation was also assessed in the reconstruction cohort to further investigate differences with this cohort between post-cancer, risk-reduction, and developmental-deformity indications. Indication for operation was included in all 5 models for breast reconstruction, with implants used for developmental deformity being associated with higher satisfaction and lower symptom frequency than implants used for post-cancer.

Another factor endorsed by ICOBRA for risk adjustment was age; 2 reconstructive and 4 aesthetic final models included age as a risk factor associated with PROMs. For the breast reconstruction cohort, higher age categories were generally associated with increased rippling dissatisfaction and higher tightness frequency when compared with the lowest age group, with magnitudes up to almost 3 times the odds. For the aesthetic cohort, however, higher age categories were generally associated with more look and rippling satisfaction and lower pain and tightness frequency; however, the CIs for the older age categories are much wider and nonsignificant due the overall younger age demographic of the aesthetic cohort. In contrast to our results, a cross-sectional study of breast cancer patients following reconstruction surgery found no significant association between age and postoperative BREAST-Q breast satisfaction score.20 However, this study included both autologous and implant-based reconstructions which limits the comparability of the findings.

Previous radiation therapy was assessed as a risk factor for inclusion in the breast reconstruction risk-adjustment analysis, and was subsequently included in the final model for implant tightness, with implant insertions into previously irradiated breasts having 1.71 times the odds of tightness all, most, or some of the time. A cohort study in 2013 found prior or postoperative radiation therapy to be associated with poorer postoperative BREAST-Q among breast cancer implant-based breast reconstruction recipients,21 and a systematic review of BREAST-Q use following oncological breast cancer concluded radiation to be generally associated with lower breast satisfaction and physical well-being.10 In contrast to these findings, none of the breast satisfaction PROMs and only 1 physical well-being PROM had previous radiation therapy included in the final model.

As with age, site type was a factor included in many of the final models for the breast reconstruction cohort. Implants inserted in a public hospital were associated with lower satisfaction and higher symptom frequency than those in a private facility. Although no studies were identified that have investigated differences in breast surgery outcomes between public and private sites in Australia, other Australian registries have found lower performance in clinical quality indicators among public sites, such as the Victorian Lung Registry22,23 and the Prostate Cancer Registry.24

Concurrent mastectomy was included in the final reconstruction model for look satisfaction. Implants with a concurrent mastectomy, synonymous in this dataset with an immediate breast reconstruction, were associated with higher look satisfaction than implants without a concurrent mastectomy. This association has been found previously, with a review of the literature regarding BREAST-Q use in oncological surgery concluding immediate reconstructions to have higher outcome satisfaction than delayed reconstructions in post-cancer implant-based breast reconstructions.10

The major strengths of this study include the large sample size and multicenter registry setting with high nationwide coverage,25 and as such the results are generalizable to the Australian population of breast implant recipients. The a priori hypotheses and clustering of standard errors at the patient level support the internal validity of this study. The registry setting, however, limited the risk factors able to be investigated to those already captured by the ABDR. As such, potential confounding by unmeasured covariates, including comorbidities, BMI, smoking, original breast size, and postoperative radiation, are a weakness of this study. The exclusion of aesthetic implants reported to be inserted in a public hospital, with a concurrent mastectomy or as part of a 2-stage insertion process due to concerns about misclassification, may limit the generalizability of the aesthetic indication cohort models. Another limitation is the lack of a validated overall BREAST-Q IS score, requiring each question to be investigated individually. We also limited the analysis to data collected at the 1-year time point to maintain the sample size for the analysis. As the registry matures, data collected at the 2- and 5-year time points can further enhance the models.

Conclusions

This study identified main operation indication and site type to be important factors associated with PROMs following breast implant reconstruction procedures for risk adjustment when benchmarking. Age was the most common factor of importance identified for risk adjustment for benchmarking aesthetic breast implant PROMs. All factors in our risk-adjustment models are included in the ICOBRA international dataset.26The risk-adjustment models developed for this study will be used for equitable benchmarking of breast implant PROMs within the ABDR. This will allow us to compare the performance of different breast devices to detect signs of potentially underperforming breast implants, while adjusting for available and relevant confounding factors. In the event that a performance outlier is identified, this would trigger notification to the Australian regulator for their further investigation, where necessary. The risk-adjustment models will also be used in annual reports and site (hospital or surgical practice) reports. In the future, risk-adjusted PROMs may be used by individual surgeons to monitor and compare their own surgical practice and patient outcomes. In addition, the risk-adjustment model development presented in this study provides a transparent model-selection process that can support international comparisons and global registry benchmarking, such as through ICOBRA.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The Australian Breast Device Registry is supported by funding from the Australian Commonwealth Department of Health.

References