-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rishub K Das, Adam G Evans, Christopher L Kalmar, Salam Al Kassis, Brian C Drolet, Galen Perdikis, Nationwide Estimates of Gender-Affirming Chest Reconstruction in the United States, 2016-2019, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 42, Issue 12, December 2022, Pages NP758–NP762, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjac193

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act, introduced in 2016, increased access to gender-affirming surgeries for transgender and gender diverse individuals. Masculinizing chest reconstruction (e.g., mastectomy) and feminizing chest reconstruction (e.g., augmentation mammaplasty), often outpatient procedures, are the most frequently performed gender-affirming surgeries. However, there is a paucity of information about the demographics of patients who undergo gender-affirming chest reconstruction.

The authors sought to investigate the incidence, demographics, and spending for ambulatory gender-affirming chest reconstruction utilizing nationally representative data from 2016 to 2019.

Employing the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample, the authors identified patients with an International Classification of Diseases diagnosis code of gender dysphoria who underwent chest reconstruction between 2016 and 2019. Demographic and clinical characteristics were recorded for each encounter.

A weighted estimate of 21,293 encounters for chest reconstruction were included (17,480 [82.1%] masculinizing and 3813 [27.9%] feminizing). Between 2016 and 2019, the number of chest surgeries per 100,000 encounters increased by 143.2% from 27.3 to 66.4 (P < 0.001). A total 12,751 (59.9%) chest surgeries were covered by private health insurance, 6557 (30.8%) were covered by public health insurance, 1172 (5.5%) were self-pay, and 813 (3.8%) had other means of payment. The median total charges were $29,887 (IQR, $21,778-$43,785) for chest reconstruction overall. Age, expected primary payer, patient location, and median income varied significantly by race (P < 0.001).

Gender-affirming chest reconstructions are on the rise, and surgeons must understand the background and needs of transgender and gender diverse patients who require and choose to undergo surgical transitions.

Under Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act, introduced in 2016, individuals may not be denied, limited, or refused health care coverage on the basis of gender identity.1 This legislation increased coverage and access to gender-affirming surgery (GAS) for transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals. Among TGD individuals experiencing gender dysphoria, GAS has been shown to improve functioning and mental health.2 Masculinizing chest reconstruction (e.g., mastectomy) and feminizing chest reconstruction (e.g., augmentation mammaplasty), often outpatient procedures, are the most frequently performed GAS.3 We investigated the incidence, demographics, and spending for ambulatory gender-affirming chest reconstruction utilizing nationally representative data from 2016 to 2019.

METHODS

Using the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample, we identified patients with an International Classification of Diseases diagnosis code of gender dysphoria who underwent chest reconstruction (Appendix). The Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample is an all-payer surgery database that captures approximately 11.8 million ambulatory surgery procedures performed in the United States annually. The study period was from 2016 to 2019. Demographic and clinical characteristics were recorded for each encounter. Race and ethnicity information were available only in 2019. The total charges were adjusted for inflation, and observations were weighted to be nationally representative. Changes in patterns over the study period were compared utilizing χ 2 tests for categorical variables and linear regression for continuous variables. Analyses were computed in Stata version 17 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), and statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided α < 0.05.

RESULTS

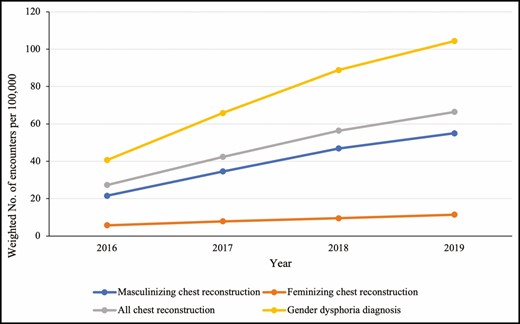

A weighted estimate of 21,293 encounters for chest reconstruction were included (17,480 [82.1%] masculinizing and 3813 [27.9%] feminizing). Between 2016 and 2019, the number of chest surgeries per 100,000 encounters increased by 143.2% from 27.3 to 66.4 (P < 0.001) (Figure 1). A total 12,751 (59.9%) chest surgeries were covered by private health insurance, 6557 (30.8%) were covered by public health insurance, 1172 (5.5%) were self-pay, and 813 (3.8%) had other means of payment (Table 1). There was no significant change in health insurance coverage during the study period. Most patients (74.2%) underwent chest reconstruction between the ages of 18 and 34 years. Only 1130 (5.3%) patients had gender-affirming chest reconstruction before age 18.

Characteristics of Transgender and Gender Diverse Patients Who Underwent Ambulatory Gender-Affirming Chest Reconstruction, 2016 to 2019a

| Patient characteristic . | Masculinizing chest reconstruction . | Feminizing chest reconstruction . | All . | Pb . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted sample sizes, no. | 12,978 | 2784 | 15,762 | |

| Age category, % | ||||

| <18 y | 6.4 | 0.4 | 5.3 | < 0.001 |

| 18-25 y | 49.3 | 20.9 | 44.2 | |

| 26-34 y | 28.6 | 36.1 | 30.0 | |

| 35-49 y | 12.2 | 26.1 | 14.7 | |

| 50-64 y | 3.2 | 14.0 | 5.2 | |

| 65+ y | 0.3 | 2.5 | 0.7 | |

| Race and ethnicity, %c | ||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 4.3 | 3.5 | 4.2 | < 0.001 |

| Black | 10.0 | 23.0 | 12.3 | |

| Hispanic | 11.4 | 15.8 | 12.2 | |

| Native American | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| Other | 5.3 | 9.5 | 6.0 | |

| White | 68.7 | 47.8 | 65.0 | |

| Expected primary payer, % | ||||

| Public health insuranced | 25.3 | 56.1 | 30.8 | < 0.001 |

| Private health insurance | 65.2 | 35.6 | 59.9 | |

| Self-pay | 5.6 | 5.3 | 5.5 | |

| Othere | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.8 | |

| Patient location, % | ||||

| Counties of >1 million population | 71.7 | 79.8 | 73.2 | < 0.001 |

| Counties of 250,000-999,999 population | 17.7 | 13.2 | 16.8 | |

| Counties of <250,000 population | 10.4 | 5.9 | 9.6 | |

| Missing data | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.4 | |

| Median income, % | ||||

| $1-47,999 | 19.1 | 28.5 | 20.8 | < 0.001 |

| $48,000-60,999 | 21.0 | 19.2 | 20.7 | |

| $61,000-81,999 | 27.4 | 23.4 | 26.7 | |

| $82,000+ | 31.5 | 26.8 | 30.6 | |

| Missing data | 1.0 | 2.2 | 1.2 | |

| Comorbidities, % | ||||

| Anxiety | 16.2 | 9.5 | 15.0 | < 0.001 |

| Asthma | 11.0 | 7.5 | 10.4 | < 0.001 |

| COPD | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 | < 0.001 |

| Depression | 11.8 | 7.5 | 11.0 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.3 | 2.8 | 1.5 | < 0.001 |

| History of alcohol use disorder | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | < 0.001 |

| History of opioid use disorder | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | < 0.05 |

| History of tobacco use disorder | 17.3 | 21.1 | 18.0 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 3.9 | 7.5 | 4.5 | < 0.001 |

| Obesity | 10.5 | 6.6 | 9.8 | < 0.001 |

| Total charges, median (IQR), $f | 30,537 (21,940-44,551) | 27,497 (21,265-40,075) | 29,887 (21,778-43,785) | < 0.001 |

| Patient characteristic . | Masculinizing chest reconstruction . | Feminizing chest reconstruction . | All . | Pb . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted sample sizes, no. | 12,978 | 2784 | 15,762 | |

| Age category, % | ||||

| <18 y | 6.4 | 0.4 | 5.3 | < 0.001 |

| 18-25 y | 49.3 | 20.9 | 44.2 | |

| 26-34 y | 28.6 | 36.1 | 30.0 | |

| 35-49 y | 12.2 | 26.1 | 14.7 | |

| 50-64 y | 3.2 | 14.0 | 5.2 | |

| 65+ y | 0.3 | 2.5 | 0.7 | |

| Race and ethnicity, %c | ||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 4.3 | 3.5 | 4.2 | < 0.001 |

| Black | 10.0 | 23.0 | 12.3 | |

| Hispanic | 11.4 | 15.8 | 12.2 | |

| Native American | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| Other | 5.3 | 9.5 | 6.0 | |

| White | 68.7 | 47.8 | 65.0 | |

| Expected primary payer, % | ||||

| Public health insuranced | 25.3 | 56.1 | 30.8 | < 0.001 |

| Private health insurance | 65.2 | 35.6 | 59.9 | |

| Self-pay | 5.6 | 5.3 | 5.5 | |

| Othere | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.8 | |

| Patient location, % | ||||

| Counties of >1 million population | 71.7 | 79.8 | 73.2 | < 0.001 |

| Counties of 250,000-999,999 population | 17.7 | 13.2 | 16.8 | |

| Counties of <250,000 population | 10.4 | 5.9 | 9.6 | |

| Missing data | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.4 | |

| Median income, % | ||||

| $1-47,999 | 19.1 | 28.5 | 20.8 | < 0.001 |

| $48,000-60,999 | 21.0 | 19.2 | 20.7 | |

| $61,000-81,999 | 27.4 | 23.4 | 26.7 | |

| $82,000+ | 31.5 | 26.8 | 30.6 | |

| Missing data | 1.0 | 2.2 | 1.2 | |

| Comorbidities, % | ||||

| Anxiety | 16.2 | 9.5 | 15.0 | < 0.001 |

| Asthma | 11.0 | 7.5 | 10.4 | < 0.001 |

| COPD | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 | < 0.001 |

| Depression | 11.8 | 7.5 | 11.0 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.3 | 2.8 | 1.5 | < 0.001 |

| History of alcohol use disorder | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | < 0.001 |

| History of opioid use disorder | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | < 0.05 |

| History of tobacco use disorder | 17.3 | 21.1 | 18.0 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 3.9 | 7.5 | 4.5 | < 0.001 |

| Obesity | 10.5 | 6.6 | 9.8 | < 0.001 |

| Total charges, median (IQR), $f | 30,537 (21,940-44,551) | 27,497 (21,265-40,075) | 29,887 (21,778-43,785) | < 0.001 |

aData are from the 2016-2019 Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample.

bP value is reported from χ 2 tests.

cRace and ethnicity were collected from hospital records in 2019 only. “Other” included multiple races.

dPublic health insurance included Medicare and Medicaid.

eIncluded no charge or other expected primary payers.

fAdjusted for inflation. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IQR, interquartile range.

Characteristics of Transgender and Gender Diverse Patients Who Underwent Ambulatory Gender-Affirming Chest Reconstruction, 2016 to 2019a

| Patient characteristic . | Masculinizing chest reconstruction . | Feminizing chest reconstruction . | All . | Pb . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted sample sizes, no. | 12,978 | 2784 | 15,762 | |

| Age category, % | ||||

| <18 y | 6.4 | 0.4 | 5.3 | < 0.001 |

| 18-25 y | 49.3 | 20.9 | 44.2 | |

| 26-34 y | 28.6 | 36.1 | 30.0 | |

| 35-49 y | 12.2 | 26.1 | 14.7 | |

| 50-64 y | 3.2 | 14.0 | 5.2 | |

| 65+ y | 0.3 | 2.5 | 0.7 | |

| Race and ethnicity, %c | ||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 4.3 | 3.5 | 4.2 | < 0.001 |

| Black | 10.0 | 23.0 | 12.3 | |

| Hispanic | 11.4 | 15.8 | 12.2 | |

| Native American | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| Other | 5.3 | 9.5 | 6.0 | |

| White | 68.7 | 47.8 | 65.0 | |

| Expected primary payer, % | ||||

| Public health insuranced | 25.3 | 56.1 | 30.8 | < 0.001 |

| Private health insurance | 65.2 | 35.6 | 59.9 | |

| Self-pay | 5.6 | 5.3 | 5.5 | |

| Othere | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.8 | |

| Patient location, % | ||||

| Counties of >1 million population | 71.7 | 79.8 | 73.2 | < 0.001 |

| Counties of 250,000-999,999 population | 17.7 | 13.2 | 16.8 | |

| Counties of <250,000 population | 10.4 | 5.9 | 9.6 | |

| Missing data | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.4 | |

| Median income, % | ||||

| $1-47,999 | 19.1 | 28.5 | 20.8 | < 0.001 |

| $48,000-60,999 | 21.0 | 19.2 | 20.7 | |

| $61,000-81,999 | 27.4 | 23.4 | 26.7 | |

| $82,000+ | 31.5 | 26.8 | 30.6 | |

| Missing data | 1.0 | 2.2 | 1.2 | |

| Comorbidities, % | ||||

| Anxiety | 16.2 | 9.5 | 15.0 | < 0.001 |

| Asthma | 11.0 | 7.5 | 10.4 | < 0.001 |

| COPD | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 | < 0.001 |

| Depression | 11.8 | 7.5 | 11.0 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.3 | 2.8 | 1.5 | < 0.001 |

| History of alcohol use disorder | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | < 0.001 |

| History of opioid use disorder | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | < 0.05 |

| History of tobacco use disorder | 17.3 | 21.1 | 18.0 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 3.9 | 7.5 | 4.5 | < 0.001 |

| Obesity | 10.5 | 6.6 | 9.8 | < 0.001 |

| Total charges, median (IQR), $f | 30,537 (21,940-44,551) | 27,497 (21,265-40,075) | 29,887 (21,778-43,785) | < 0.001 |

| Patient characteristic . | Masculinizing chest reconstruction . | Feminizing chest reconstruction . | All . | Pb . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted sample sizes, no. | 12,978 | 2784 | 15,762 | |

| Age category, % | ||||

| <18 y | 6.4 | 0.4 | 5.3 | < 0.001 |

| 18-25 y | 49.3 | 20.9 | 44.2 | |

| 26-34 y | 28.6 | 36.1 | 30.0 | |

| 35-49 y | 12.2 | 26.1 | 14.7 | |

| 50-64 y | 3.2 | 14.0 | 5.2 | |

| 65+ y | 0.3 | 2.5 | 0.7 | |

| Race and ethnicity, %c | ||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 4.3 | 3.5 | 4.2 | < 0.001 |

| Black | 10.0 | 23.0 | 12.3 | |

| Hispanic | 11.4 | 15.8 | 12.2 | |

| Native American | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| Other | 5.3 | 9.5 | 6.0 | |

| White | 68.7 | 47.8 | 65.0 | |

| Expected primary payer, % | ||||

| Public health insuranced | 25.3 | 56.1 | 30.8 | < 0.001 |

| Private health insurance | 65.2 | 35.6 | 59.9 | |

| Self-pay | 5.6 | 5.3 | 5.5 | |

| Othere | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.8 | |

| Patient location, % | ||||

| Counties of >1 million population | 71.7 | 79.8 | 73.2 | < 0.001 |

| Counties of 250,000-999,999 population | 17.7 | 13.2 | 16.8 | |

| Counties of <250,000 population | 10.4 | 5.9 | 9.6 | |

| Missing data | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.4 | |

| Median income, % | ||||

| $1-47,999 | 19.1 | 28.5 | 20.8 | < 0.001 |

| $48,000-60,999 | 21.0 | 19.2 | 20.7 | |

| $61,000-81,999 | 27.4 | 23.4 | 26.7 | |

| $82,000+ | 31.5 | 26.8 | 30.6 | |

| Missing data | 1.0 | 2.2 | 1.2 | |

| Comorbidities, % | ||||

| Anxiety | 16.2 | 9.5 | 15.0 | < 0.001 |

| Asthma | 11.0 | 7.5 | 10.4 | < 0.001 |

| COPD | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 | < 0.001 |

| Depression | 11.8 | 7.5 | 11.0 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.3 | 2.8 | 1.5 | < 0.001 |

| History of alcohol use disorder | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | < 0.001 |

| History of opioid use disorder | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | < 0.05 |

| History of tobacco use disorder | 17.3 | 21.1 | 18.0 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 3.9 | 7.5 | 4.5 | < 0.001 |

| Obesity | 10.5 | 6.6 | 9.8 | < 0.001 |

| Total charges, median (IQR), $f | 30,537 (21,940-44,551) | 27,497 (21,265-40,075) | 29,887 (21,778-43,785) | < 0.001 |

aData are from the 2016-2019 Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample.

bP value is reported from χ 2 tests.

cRace and ethnicity were collected from hospital records in 2019 only. “Other” included multiple races.

dPublic health insurance included Medicare and Medicaid.

eIncluded no charge or other expected primary payers.

fAdjusted for inflation. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IQR, interquartile range.

Temporal trends in ambulatory gender-affirming chest reconstruction per 100,000 encounters, 2016-2019.

A total 14,511 (68.2%) individuals undergoing chest reconstruction had a median income of <$82,000 US. The median total charges were $30,537 US (IQR, $21,940-$44,551 US) for masculinizing chest reconstruction, $27,497 (IQR, $21,265-$40,075 US) for feminizing chest reconstruction, and $29,887 US (IQR, $21,778-$43,785 US) for chest reconstruction overall. The total charges for chest reconstruction did not change during the study period and were 10.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.3% to 20.5%) lower compared with analogous procedures performed in cisgender patients. Total charges for chest surgeries were 12.0% (95% CI, 4.0% to 20.1%) higher among patients with private health insurance compared with public health insurance.

For individuals undergoing gender-affirming chest reconstruction in 2019, 4952 (65.0%) were White, 933 (12.3%) were Black, 928 (12.2%) were Hispanic, 318 (4.2%) were Asian or Pacific Islander, 26 (0.3%) were Native American, and 457 (6.0%) were another race/ethnicity. Age, expected primary payer, patient location, and median income varied significantly by race (P < 0.001). Compared with White patients, Black (odds ratio [OR], 3.36; 95% CI, 2.43 to 4.63; P < 0.001), Hispanic (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.26 to 2.36; P < 0.001), Native American (OR, 3.46; 95% CI, 1.36 to 8.80; P = 0.009), and other race/ethnicity (OR, 2.88; 95% CI, 1.60 to 5.18; P < 0.001) patients were more likely to be covered by public health insurance. Black (OR, 3.71; 95% CI, 2.72 to 5.09; P < 0.001), Hispanic (OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.34 to 2.60; P < 0.001), Asian or Pacific Islander (OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.34 to 2.49; P < 0.001), and other race/ethnicity (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.34 to 3.98; P = 0.003) patients were more likely to be from large urban areas than White patients. A median income <$82,000 US was more likely among Black patients (OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.63 to 2.98; P < 0.001) than White patients. Total charges for Hispanic and Asian or Pacific Islander patients were 21.9% (95% CI, 13.0%3 to 0.9%) and 13.3% (95% CI, 2.6% to 24.0%) higher than those for White TGD patients, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This cross-sectional study employing national ambulatory surgery data is the largest investigation of gender-affirming chest reconstruction to date. The results demonstrate substantial increases in the incidence of ambulatory gender-affirming chest reconstruction that are concordant with annual data on GAS from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons and reported trends in the prescription of gender-affirming hormone therapy.4,5 Patient demographics varied significantly by type of surgery, either masculinizing or feminizing chest reconstruction, highlighting the need for stratification in outcomes research and practice improvements.6

Generally, most TGD patients were covered by either public or private health insurance for these procedures, representing a shift from a predominance of self-payers reported in previous studies.7 Financial insecurity and limited resources are significant barriers to gender-affirming care given the magnitude of costs for surgery and hormone therapy.5 This study found that most TGD individuals undergoing chest reconstruction had a median income <$82,000 US. The substantial shift in payer status and increase in procedures after the introduction of Section 1557 underscore the importance of policy in national discussions about access to gender-affirming care. Amid a legislative assault on the rights of TGD people by over 35 state legislatures, gender-affirming surgeons and surgeon-allies must support inclusive policy that improves access to healthcare for TGD communities.8,9 Surgeons who offer gender-affirming procedures should live authentically as an advocate even outside of clinical and research settings.

Racial and ethnic disparities pervade the US healthcare system.10 These disparities are amplified for individuals with other intersecting marginalized identities.11-13 Our findings suggest that among other differences, cost-related disparities may exist for TGD people of color. Total charges vary by hospital system and procedures performed. Based on the pattern of increased charges, it is likely that people of color are affected by system-level factors that limit their ability to access lower cost care. Geography is an important determinant of total charges for surgical procedures and may contribute to the observed disparities. Studies investigating Medicare claims find that Black, Hispanic, and Asian or Pacific Islander patients are more likely to live in urban areas where the charges for care are higher.10 The same pattern was identified in the sample of TGD patients undergoing gender-affirming chest reconstruction. Systemic factors such as barriers to routine health maintenance and the resulting health disparities may also require additional perioperative resources contributing to increased charges.

This study was limited by the reliability of diagnosis codes to identify TGD patients, sampling error, and the absence of cost to charge ratio data. Information about which states or providers performed the most reconstructions was not available. Future studies should investigate out-of-pocket costs for gender-affirming chest reconstruction and other surgeries in addition to evaluating interventions that improve access to gender-affirming care such as training more surgeons.

CONCLUSIONS

Gender-affirming chest reconstructions are on the rise, and surgeons must understand the background and needs of TGD patients who require and choose to undergo surgical transitions. Furthermore, racial and ethnic disparities may limit access and affect outcomes for GAS.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

This project was supported by funding from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Clinical Translational Science Award (CTSA) Program, Award Number 5UL1TR002243-03.

REFERENCES

- ambulatory surgical procedures

- demography

- income

- insurance

- mammaplasty

- outpatients

- surgical procedures, operative

- diagnosis

- mastectomy

- public health medicine

- gender

- thoracic surgery procedures

- sex reassignment surgery

- international classification of diseases

- chest wall reconstruction

- gender dysphoria

- health insurance, private

- uninsured medical expense

- spending

- patient protection and affordable care act

- healthcare payer

- patient tracking

- transgender persons