-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lukasz Preibisz, Florence Boulmé, Z Paul Lorenc, Barbed Polydioxanone Sutures for Face Recontouring: Six-Month Safety and Effectiveness Data Supported by Objective Markerless Tracking Analysis, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 42, Issue 1, January 2022, Pages NP41–NP54, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjab359

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Barbed polydioxanone (PDO) sutures allowing for minimally invasive skin lifting are broadly and increasingly used in aesthetic dermatology.

To describe utilization of diverse barbed PDO sutures for aesthetic facial corrections in Caucasian patients, to evaluate long-term safety and to demonstrate effectiveness in skin tightening, redefinition of facial contours, and tissue elevation.

A retrospective chart review of patients routinely treated with barbed PDO sutures on face was performed. Aesthetic improvement was evaluated at 6-, 12- and 24-week posttreatment by the treating physician, patients, and an independent photographic reviewer. Patient’s satisfaction with treatment outcome was evaluated. Procedure effects were also objectively measured by markerless tracking analysis.

Sixty patients were treated with a total of 388 barbed sutures in various anatomical areas and followed-up for 24 weeks. At Week 24, the aesthetic improvement rate was 80% to 100% (depending on the evaluator), skin movements related to pre-treatment photographs showed significant changes across several different anatomical regions, and 97% of patients were satisfied with the overall treatment outcome. Transient, mild, and short-lasting adverse events, mostly pain and hematoma, occurred in 15% of patients.

Barbed PDO sutures are safe and highly effective for aesthetic corrections, with results lasting for at least 24 weeks.

Suture- or thread-lifting are terms employed in aesthetic dermatology and surgery for procedures intended to elevate or realign sagging skin by means of a suture. It covers a variety of methods, which fundamentally differ in terms of invasiveness (open surgery, small skin incision, incisionless), implantation technique (anchored, free-floating), and longevity (non-absorbable, absorbable, mixed) of the suture. Furthermore, available sutures differ in their structure (monofilament, multifilament), surface characteristics (plain, coiled, barbed, cogged, with cones), dimensions, and design of introducing the needle/cannula (needleless, integrated on one or both ends of a suture, or housing the inserted part of a suture).1-3 Such diversity reflects the versatility of sutures utilized in facial recontouring but also attempts to improve effectiveness and overcome drawbacks of individual devices and techniques.

In view of increasing demand for minimally invasive and affordable aesthetic corrections with short downtime, incisionless skin lifting with free-floating absorbable polydioxanone (PDO) sutures recently became popular.4 PDO is an absorbable synthetic polymer, which has been in clinical utilization for soft tissue approximation since the early 1980s.5 Monofilament sutures show desirable characteristics for skin suspension, such as high tensile strength and good tolerance after implantation. PDO is slowly hydrolyzed in the body and fully absorbed in 6 to 7 months.5-7

Such devices basically consist of a suture housed into the lumen of an insertion needle and bent backward at the needle tip. During needle insertion into the desired tissue, the suture is introduced by following the needle path and then remains in place on needle removal, likely due to high friction with surrounding tissue.8 This design was inspired in part by skin rejuvenation benefits of acupuncture, which may be partly attributed to activation of wound healing/tissue regeneration mechanisms in response to tissue injury caused by the needle puncture.6,9 A suture left in the initial wound channel extends the length of the healing process, resulting in enhanced skin volume and subsequent remodeling. Long-term increases in collagen and elastin deposition along the suture continue for at least 6 months after complete absorption of the suture.10-12

Bidirectionally barbed PDO sutures are employed mostly for vertical skin repositioning; on needle removal, the manual pulling of the suture’s extruding end allows for realignment of the tissue hooked onto barbs into the desired position. In contrast to classic suspension sutures, which pull the skin towards an anchoring point, self-anchoring sutures redistribute and tighten the skin in a new position.1,8 To obtain an optimal aesthetical correction on a defined facial area, the choice of the appropriate barbed PDO suture model to be utilized is essential. For correction of a given anatomical area, the combination of the following parameters must be taken in account: type of correction needed (level of tissue elevation), selection of the type and the number of barbed PDO sutures needed (ie, higher number and longer ones for a cheek lift than a brow lift), and length and thickness of the barbed PDO sutures depending of the clinical characteristics of the tissue to be corrected (ie, thicker sutures to be employed by older or overweight patients presenting heavier facial tissue).

Although this treatment modality is highly appealing, especially in terms of simplicity, minimal invasiveness, and virtually no downtime, published clinical data were surprisingly scarce until 2017.13,14 Several studies have recently emerged in the literature but are mostly limited to an Asian population.15-19 The present study was therefore undertaken in Caucasian patients to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of barbed PDO sutures for skin lifting over 24 weeks in a real-life clinical setting. In addition to assessments by the treating physician, an independent photographic reviewer, and the patients, a novel, markerless tracking analysis of skin surface was employed to impartially measure treatment effects.

METHODS

Data were collected by utilizing a chart review of consecutive patients routinely treated with barbed PDO sutures in the first author’s practice between April 2017 and April 2018 and followed-up 6 months posttreatment. Following Polish law, the Ethics Committee of Warsaw was notified of this retrospective study and conducted in line with the principles of the revised Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Each patient provided a written informed consent for treatment and utilization of collected data for research purposes, including photographs.

Patients

Barbed PDO suture treatment was typically applied to adults presenting with mild to moderate signs of aging and who desired either a subtle correction to maintain a natural look or a minimally invasive intervention to improve their appearance. The absence of any additional aesthetical or surgical procedure in the treatment area for 24 weeks following PDO suture implantation was the sole criteria employed for retrospective patient selection. Patient demographics are described in Table 1.

| Patients . | . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 60 . | 100 . |

| Age (y) | Mean | 45 | – |

| Median | 43 | – | |

| Range | 24-64 | – | |

| Sex | Female | 59 | 98 |

| Male | 1 | 2 | |

| Race | Caucasian | 60 | 100 |

| Weight (kg) | Mean | 66 | — |

| Median | 63 | — | |

| Range | 48-107 | — | |

| Follow-up visits | Week 6 | 56 | 93 |

| Week 12 | 57 | 95 | |

| Week 24 | 56 | 93 |

| Patients . | . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 60 . | 100 . |

| Age (y) | Mean | 45 | – |

| Median | 43 | – | |

| Range | 24-64 | – | |

| Sex | Female | 59 | 98 |

| Male | 1 | 2 | |

| Race | Caucasian | 60 | 100 |

| Weight (kg) | Mean | 66 | — |

| Median | 63 | — | |

| Range | 48-107 | — | |

| Follow-up visits | Week 6 | 56 | 93 |

| Week 12 | 57 | 95 | |

| Week 24 | 56 | 93 |

| Patients . | . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 60 . | 100 . |

| Age (y) | Mean | 45 | – |

| Median | 43 | – | |

| Range | 24-64 | – | |

| Sex | Female | 59 | 98 |

| Male | 1 | 2 | |

| Race | Caucasian | 60 | 100 |

| Weight (kg) | Mean | 66 | — |

| Median | 63 | — | |

| Range | 48-107 | — | |

| Follow-up visits | Week 6 | 56 | 93 |

| Week 12 | 57 | 95 | |

| Week 24 | 56 | 93 |

| Patients . | . | n . | % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 60 . | 100 . |

| Age (y) | Mean | 45 | – |

| Median | 43 | – | |

| Range | 24-64 | – | |

| Sex | Female | 59 | 98 |

| Male | 1 | 2 | |

| Race | Caucasian | 60 | 100 |

| Weight (kg) | Mean | 66 | — |

| Median | 63 | — | |

| Range | 48-107 | — | |

| Follow-up visits | Week 6 | 56 | 93 |

| Week 12 | 57 | 95 | |

| Week 24 | 56 | 93 |

Barbed PDO Sutures

All patients were treated with barbed PDO sutures (Princess LIFT-PDO manufactured by MediFirst Co., Ltd., Chungnam, Korea, and distributed by Croma-Pharma GmbH, Leobendorf, Austria) as well as Lead Fine Lift PDO (Grand Aespio, Inc., Seoul, Korea). The portfolio of CE-marked devices contains 3 models, which differ in the dimensions of the suture and the needle (Table 2).

| Subtype . | Model . | Code . | Needle/cannula dimensions . | . | Suture dimensions . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | Gauge (G) . | Length (mm) . | Diameter (USP) . | Length (mm) . |

| Barb II | Needle | B1 | 21 | 90 | 3-0 | 150 |

| Needle | B2 | 23 | 60 | 4-0 | 90 | |

| Cannula | B3 | 19 | 90 | 1-0 | 145 |

| Subtype . | Model . | Code . | Needle/cannula dimensions . | . | Suture dimensions . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | Gauge (G) . | Length (mm) . | Diameter (USP) . | Length (mm) . |

| Barb II | Needle | B1 | 21 | 90 | 3-0 | 150 |

| Needle | B2 | 23 | 60 | 4-0 | 90 | |

| Cannula | B3 | 19 | 90 | 1-0 | 145 |

PDO, polydioxanone.

| Subtype . | Model . | Code . | Needle/cannula dimensions . | . | Suture dimensions . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | Gauge (G) . | Length (mm) . | Diameter (USP) . | Length (mm) . |

| Barb II | Needle | B1 | 21 | 90 | 3-0 | 150 |

| Needle | B2 | 23 | 60 | 4-0 | 90 | |

| Cannula | B3 | 19 | 90 | 1-0 | 145 |

| Subtype . | Model . | Code . | Needle/cannula dimensions . | . | Suture dimensions . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | Gauge (G) . | Length (mm) . | Diameter (USP) . | Length (mm) . |

| Barb II | Needle | B1 | 21 | 90 | 3-0 | 150 |

| Needle | B2 | 23 | 60 | 4-0 | 90 | |

| Cannula | B3 | 19 | 90 | 1-0 | 145 |

PDO, polydioxanone.

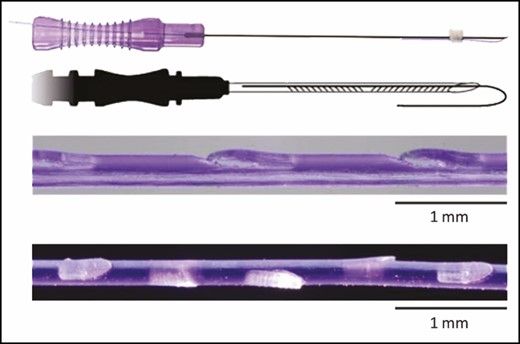

Two different models of bidirectional barbed PDO suture were utilized (Figure 1): on the needle model, barbs are located on one side of the suture following a straight pattern, whereas the barbs of the cannula model are helically oriented around the suture. The main function of the barbs is to anchor the suture into the subdermal tissue.

Photograph of the Barb II needle model, illustration of Barb II needle model, and microscopical photographs of the barbed suture for the needle (upper part) and the cannula (lower part) models (printed with permission of Croma-Pharma GmbH, Leobendorf, Austria).

Needles/Cannula

The suture is housed in thin-walled needles and cannula whose gauges and lengths are described in Table 2. The coated stainless-steel needles are sharp, and the cannula has a blunt end.

Implantation Technique

PDO sutures must only be utilized by physicians who have received specific training on the implantation techniques and have extensive anatomical knowledge of the area to be implanted, especially in the different gliding planes in each zone to avoid nerve or major vessel damage.

PDO suture implantation is minimally invasive, requires approximately 20 to 60 minutes depending on the number of sutures to be utilized and the region to be treated, and entails the following steps (Video 1, available online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com):

The wrinkle lines of interest are marked with a white pen while the patient is sitting;

The treatment area is cleaned with a disinfectant. Optionally, a local anesthetic is injected at the planned entry point location of the needle/cannula and/or along planned pathway of sutures;

The entire needle/cannula is inserted subcutaneously into the skin, with the entry point around 1 cm superior to the intended suture position. For cannula, the skin is first punctured with a 18G needle to create an entry point for insertion. A sewing technique (alternating up and down movements of the needle/cannula between the dermis and subcutis) is recommended; 8

Light pressure is applied on the treated area to maintain suture placement while the needle/cannula is being removed. The extruding end of the suture is then pulled until the desired elevation effect is obtained (the barbs are designed to keep the skin in the new position). Finally, the extruding end is cut off with sterile scissors as close as possible to skin surface, allowing for retraction of suture end into the skin, when the tension is released;

The model and number of sutures implanted in a specific anatomic area depend on the thickness and laxity of the skin as well as the desired level of correction and anatomical area considered;

A slight and delicate overcorrection is necessary considering gravity and the decrease of suture strength over time; the associated downtime is approximately 2 weeks; and

On completion, the skin surface is cleaned and, if necessary, a cool pack may be applied on treated areas approximately 20 minutes.

Safety Follow-up and Outcome Assessments

Patients were routinely advised to contact their physician in case of any adverse events and to return for follow-up assessments approximately 6, 12, and 24 weeks posttreatment. Information on adverse events and concomitant medication(s) or procedure(s) was collected at each visit.

Three photographs (front/side views) of each patient’s face were routinely taken before treatment (baseline) and at each follow-up visit with the handheld Vectra H1 3D imaging camera (Canfield Scientific, Inc., Parsippany, NJ, USA). For the same timepoints, aesthetic improvement related to baseline was independently evaluated by the physician, the patient, and, subsequently, an independent photographic reviewer utilizing the Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS), a 5-grade instrument ranging from “very much improved” to “worse.” 20 At the final visit, each patient also assessed overall satisfaction with treatment outcome employing 1 of the following categories: “very satisfied,” “satisfied,” or “not satisfied”; moreover, patients were asked if they would like to undergo the same procedure again and if they would recommend this treatment to others.

Markerless Tracking Analysis

To support the present study, collected photographs were processed with Canfield Capture software and sent to Canfield Scientific, Inc. for markerless tracking analysis of posttreatment skin surface changes related to baseline. Markerless tracking is a high accuracy, non-contact, and non-invasive optical imaging technique, which quantitatively tracks skin movement and deformation under mechanical perturbations. It employs digital image correlation to map each pixel-patch from a baseline image to its corresponding pixel-patch in a follow-up image. By applying digital image correlation across an entire image, the technique achieves a dense mapping between baseline and follow-up images. Whereas older skin tracking techniques relied on a small set of reproducible anatomical markers or tattoos for correspondence, this technique builds a dense correspondence of tens of thousands of points across the entire image, thus enabling metrics to be computed for any area of interest. Surface changes are visualized through vectors drawn on patient’s photographs; different parameters (major strain or displacement) therefore can be objectively measured and analyzed.21 A statistical analysis of resulting data was performed employing Wilcoxon signed rank test. Accuracy of this methodology has been assessed utilizing a woven flesh-toned elastic fabric that mimics the appearance and strain properties of skin in an experimental setting. Tests were performed on a rectangular sample of the fabric measuring 150 × 220 mm. The results of the stretch experiment demonstrate that markerless tracking achieves a high degree of accuracy. We observed an average absolute difference in axial strain and principal strain of 0.24% and 0.40%, respectively, between the markerless tracking measurements and the reference standard measurements.

RESULTS

Sixty Caucasian patients were consecutively treated with barbed PDO sutures, 98% of whom were female (59 female and 1 male); 3 patients (5%) did not return for follow-up assessments, and 1 patient attended Week 12 follow-up visit only (Table 1). At baseline, their median age was 43 years (range, 31-64 years) and median body weight was 63 kg (range, 48-107 kg).

The number and model of sutures implanted per patient were determined by the patient’s needs and treatment area (Table 3), as assessed by the treating physician. Overall, 388 sutures were implanted into 60 patients (4-6 sutures per patient on average per treatment area, ranging from 2 to 16). Only 18% of patients required the utilization of injectable local anesthetic pretreatment; all of these were treated in the midface area.

| Treatment area . | No. of patients . | PDO model (codea) . | No. of sutures per patient . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | Mean . | Range . |

| Midface (cheeks) | 53 | Barb II (B1/B2/B3) | 5.5 | 2-10 |

| Eyebrows | 13 | Barb II (B2) | 5.9 | 2-8 |

| Jawline | 4 | Barb II (B3) | 4.5 | 2-6 |

| Treatment area . | No. of patients . | PDO model (codea) . | No. of sutures per patient . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | Mean . | Range . |

| Midface (cheeks) | 53 | Barb II (B1/B2/B3) | 5.5 | 2-10 |

| Eyebrows | 13 | Barb II (B2) | 5.9 | 2-8 |

| Jawline | 4 | Barb II (B3) | 4.5 | 2-6 |

PDO, polydioxanone. aSee Table 2 for PDO suture model codes.

| Treatment area . | No. of patients . | PDO model (codea) . | No. of sutures per patient . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | Mean . | Range . |

| Midface (cheeks) | 53 | Barb II (B1/B2/B3) | 5.5 | 2-10 |

| Eyebrows | 13 | Barb II (B2) | 5.9 | 2-8 |

| Jawline | 4 | Barb II (B3) | 4.5 | 2-6 |

| Treatment area . | No. of patients . | PDO model (codea) . | No. of sutures per patient . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | Mean . | Range . |

| Midface (cheeks) | 53 | Barb II (B1/B2/B3) | 5.5 | 2-10 |

| Eyebrows | 13 | Barb II (B2) | 5.9 | 2-8 |

| Jawline | 4 | Barb II (B3) | 4.5 | 2-6 |

PDO, polydioxanone. aSee Table 2 for PDO suture model codes.

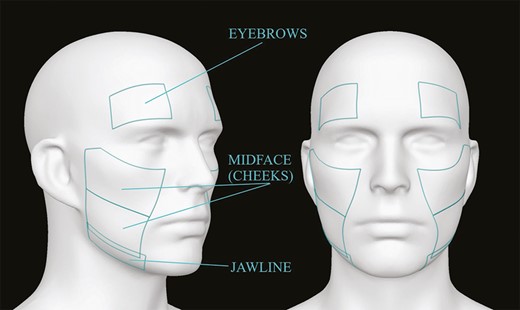

Typical suture implantation patterns are illustrated in Figure 2 for various anatomical areas. Overall, 83% of the patients were treated in a single area and 17% in 2 different anatomic areas. A bottom implantation was preferentially employed for elevation of the jawline. In patients with thicker or heavier skin, especially older or male or overweight patients, a barbed cannula model housing a thicker suture (1-0 USP) was preferentially chosen over the barbed needle model, because this provided a stronger lift. All procedures were performed in a single treatment session and placed bilaterally, except for 1 patient who desired treatment only of the left eyebrow to correct a slight asymmetry.

Schematic description of anatomical areas analyzed by markerless tracking analysis adapted from an original photograph from Canfield Scientific, Inc. (Parsippany, NJ).

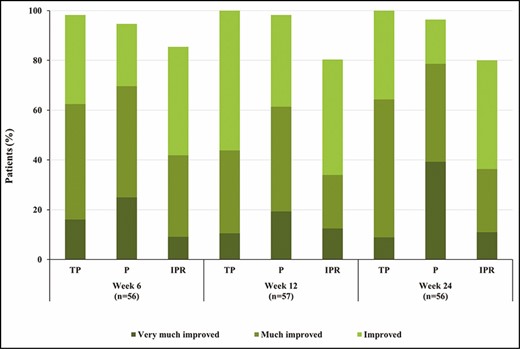

Aesthetic improvement assessments at 6, 12, and 24 weeks after polydioxanone sutures treatment performed by treating physician (TP), patient (P), and independent photographic reviewer (IPR) employing the Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale. No change was reported in the remaining patients.

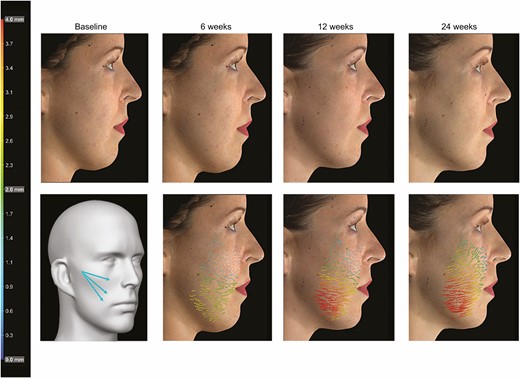

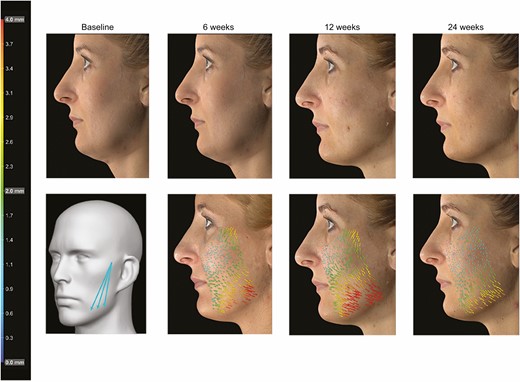

Markerless tracking analysis featuring this 36-year-old female patient needing midface skin tightening and treated with 3 Barb II (needle 23G/60 mm) polydioxanone sutures on right upper cheek. Photographs show the patient at baseline and 6, 12, and 24 weeks after implantation. Suture implantation pattern (printed with permission from Croma-Pharma GmbH), analysis of skin movements, and vectors indicate intensity (see color scale) and direction of skin displacement (Figures 4-6) or major strain (Figure 7) compared with the baseline pretreatment photograph.

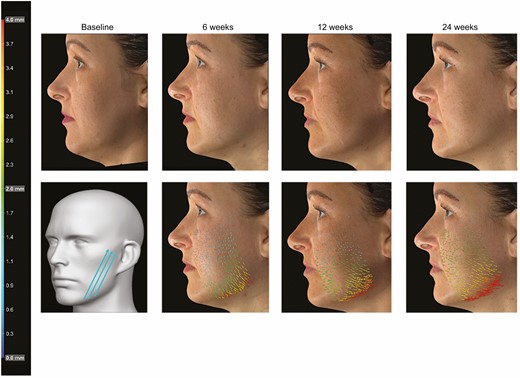

Markerless tracking analysis featuring this 41-year-old female patient presenting with a mild sagging tissue and treated with 3 Barb II (needle 21G/90 mm) polydioxanone sutures on left lower cheek. Photographs show the patient at baseline and 6, 12, and 24 weeks after implantation. Suture implantation pattern (with permission of Croma-Pharma GmbH), analysis of skin movements, and vectors indicate intensity (see color scale) and direction of skin displacement (Figures 4-6) or major strain (Figure 7) compared with the baseline pretreatment photograph.

Treatment satisfaction was performed by the patient, the treating physician, and subsequently by an independent photographic reviewer, all employing the same 5-point GAIS scale and evaluating the aesthetic improvement related to baseline at each follow-up visit. In all instances, assessments demonstrated a sustained improvement over time (Figure 3). Six weeks after treatment, 95% of the patients rated the treatment outcome as improved (25% “very improved,” 45% “much improved,” and 25% “improved” assessments); this level of improvement reached 98% (19% “very improved,” 42% “much improved,” and 37% “improved”) at the Week 12 follow-up visit and 96% (39% “very improved,” 39% “much improved,” and 18% “improved”) at the Week 24 posttreatment visit. The treating physician’s GAIS assessment was in good agreement with the patient’s rating. The ratings of the independent photographic reviewer’s evaluations were slightly lower (overall improvement of 85% at Week 6, 80% at Week 12, and 80% at Week 24) but directionally consistent with the live assessments of the treating physician and the patients; this may in part be due to the differences between live 3-dimensional (3D) assessments vs static 2D photographic assessments. Of note, 96% of patients were satisfied with their treatment outcome at Week 24, 91% of them would undergo the same procedure again, and 100% of the patients who answered the questionnaire would recommend this treatment to others.

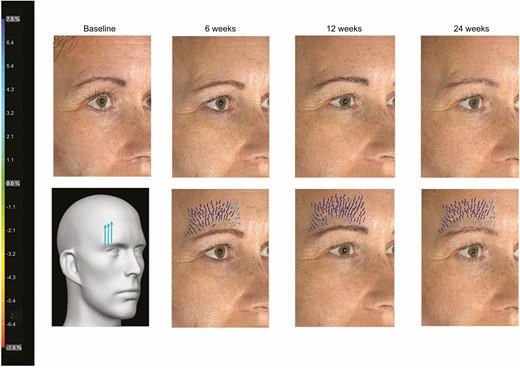

The markerless tracking analysis was performed on predefined anatomical areas utilizing available photographs taken at baseline and follow-up visits (Figure 4). Two parameters were employed to investigate skin changes on suture implantation: (1) major strain (%) describing skin extension or stretching, and (2) displacement (in millimeters) showing directional movement along the skin. Figures 4 to 7 show the treatment outcomes for patients treated with barbed PDO sutures on the midface (cheeks), the jowls, and the lateral eyebrows according to the implantation pattern schemas (described respectively in Figures 4-7). The treatment effects can be observed by comparing photographs taken at different visits (photos B/C/D compared with A before treatment). An implantation of Barb II PDO sutures in the upper (Figure 4) or lower cheeks (Figure 5) resulted in skin tightening with skin movements of up to 4.0 mm, as illustrated by the size and color of the resulting vectors drawn on the pictures. A significant improvement of the jawline contour—following bottom implantation of barbed cannula sutures to correct sagging jowls in this patient—is shown in Figure 6. Barbed PDO sutures were also employed for the elevation of the lateral eyebrows of the patient shown in Figure 7.

The quantification of these changes is summarized in Table 4 (major strain) and Table 5 (displacement). Statistically significant effects were observed for mostly all treated anatomical areas. For example, the major strain and displacement changes of the midface relative to baseline were highly significant (P ≤ 0.0001); these improvements remained stable until Week 12 posttreatment and only slightly reduced thereafter. Although the measurement of the jawline at Week 24 did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.056), an anatomically measurable effect was still demonstrated; the lack of statistical significance in this anatomic area may be simply related to the lower number of patients treated in this region.

Changes of Major Strain Parameter (%), Related to Baseline, in Areas Treated by Barbed PDO Sutures and Analyzed by Markerless Tracking Analysis After 6, 12, and 24 Weeks

| Treatment area . | No. of patientsa . | Week 6 . | . | . | . | Week 12 . | . | . | . | Week 24 . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . |

| Midface (cheeks) | 49 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 7.4 | <0.0001 | 3.5 | 1.4 | 6.8 | <0.0001 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 5.9 | <0.0001 |

| Eyebrows | 10 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 7.0 | <0.001 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 11.2 | 0.005 | 3.1 | 1.2 | 5.8 | <0.0001 |

| Jawline | 4 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 6.4 | 0.018 | 3.6 | 0.8 | 4.4 | 0.018 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 6.2 | 0.056 |

| Treatment area . | No. of patientsa . | Week 6 . | . | . | . | Week 12 . | . | . | . | Week 24 . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . |

| Midface (cheeks) | 49 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 7.4 | <0.0001 | 3.5 | 1.4 | 6.8 | <0.0001 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 5.9 | <0.0001 |

| Eyebrows | 10 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 7.0 | <0.001 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 11.2 | 0.005 | 3.1 | 1.2 | 5.8 | <0.0001 |

| Jawline | 4 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 6.4 | 0.018 | 3.6 | 0.8 | 4.4 | 0.018 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 6.2 | 0.056 |

PDO, polydioxanone, SD, standard deviation. aNumber of analyzed pictures, which may differ from the number of treated patients at baseline due to loss of follow-up until Week 24 or insufficient quality of the photographs taken or both.

Changes of Major Strain Parameter (%), Related to Baseline, in Areas Treated by Barbed PDO Sutures and Analyzed by Markerless Tracking Analysis After 6, 12, and 24 Weeks

| Treatment area . | No. of patientsa . | Week 6 . | . | . | . | Week 12 . | . | . | . | Week 24 . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . |

| Midface (cheeks) | 49 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 7.4 | <0.0001 | 3.5 | 1.4 | 6.8 | <0.0001 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 5.9 | <0.0001 |

| Eyebrows | 10 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 7.0 | <0.001 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 11.2 | 0.005 | 3.1 | 1.2 | 5.8 | <0.0001 |

| Jawline | 4 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 6.4 | 0.018 | 3.6 | 0.8 | 4.4 | 0.018 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 6.2 | 0.056 |

| Treatment area . | No. of patientsa . | Week 6 . | . | . | . | Week 12 . | . | . | . | Week 24 . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . |

| Midface (cheeks) | 49 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 7.4 | <0.0001 | 3.5 | 1.4 | 6.8 | <0.0001 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 5.9 | <0.0001 |

| Eyebrows | 10 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 7.0 | <0.001 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 11.2 | 0.005 | 3.1 | 1.2 | 5.8 | <0.0001 |

| Jawline | 4 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 6.4 | 0.018 | 3.6 | 0.8 | 4.4 | 0.018 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 6.2 | 0.056 |

PDO, polydioxanone, SD, standard deviation. aNumber of analyzed pictures, which may differ from the number of treated patients at baseline due to loss of follow-up until Week 24 or insufficient quality of the photographs taken or both.

Changes of Displacement Parameter (Mm), Related to Baseline, in Areas Treated by Barbed PDO Sutures and Analyzed by Markerless Tracking Analysis After 6, 12, and 24 Weeks

| Treatment area . | No. of patientsa . | Week 6 . | . | . | . | Week 12 . | . | . | . | Week 24 . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . |

| Midface (cheeks) | 49 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 2.8 | <0.0001 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 6.8 | <0.0001 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 3.3 | <0.0001 |

| Eyebrows | 10 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 0.002 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 3.9 | <0.0001 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 3.7 | 0.002 |

| Jawline | 4 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 0.026 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 0.038 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 0.018 |

| Treatment area . | No. of patientsa . | Week 6 . | . | . | . | Week 12 . | . | . | . | Week 24 . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . |

| Midface (cheeks) | 49 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 2.8 | <0.0001 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 6.8 | <0.0001 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 3.3 | <0.0001 |

| Eyebrows | 10 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 0.002 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 3.9 | <0.0001 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 3.7 | 0.002 |

| Jawline | 4 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 0.026 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 0.038 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 0.018 |

PDO, polydioxanone; SD, standard deviation. aNumber of analyzed pictures, which may differ from the number of treated patients at baseline due to loss of follow-up until Week 24 and/or insufficient quality of the photographs taken.

Changes of Displacement Parameter (Mm), Related to Baseline, in Areas Treated by Barbed PDO Sutures and Analyzed by Markerless Tracking Analysis After 6, 12, and 24 Weeks

| Treatment area . | No. of patientsa . | Week 6 . | . | . | . | Week 12 . | . | . | . | Week 24 . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . |

| Midface (cheeks) | 49 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 2.8 | <0.0001 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 6.8 | <0.0001 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 3.3 | <0.0001 |

| Eyebrows | 10 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 0.002 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 3.9 | <0.0001 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 3.7 | 0.002 |

| Jawline | 4 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 0.026 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 0.038 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 0.018 |

| Treatment area . | No. of patientsa . | Week 6 . | . | . | . | Week 12 . | . | . | . | Week 24 . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . | Mean . | SD . | Max . | P . |

| Midface (cheeks) | 49 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 2.8 | <0.0001 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 6.8 | <0.0001 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 3.3 | <0.0001 |

| Eyebrows | 10 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 0.002 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 3.9 | <0.0001 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 3.7 | 0.002 |

| Jawline | 4 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 0.026 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 0.038 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 0.018 |

PDO, polydioxanone; SD, standard deviation. aNumber of analyzed pictures, which may differ from the number of treated patients at baseline due to loss of follow-up until Week 24 and/or insufficient quality of the photographs taken.

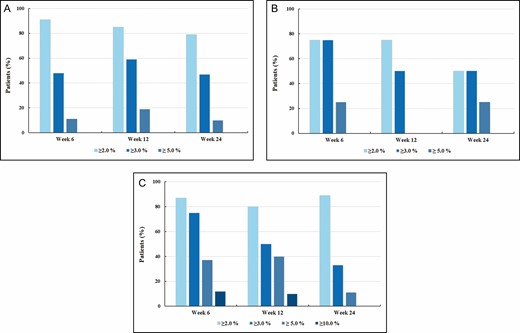

Twenty-four weeks after implantation, skin lifting was still observed in many patients (Figure 8). At Week 24, approximately 50% of the patients treated in the midface (cheeks) (Figure 8A) and the jawline (Figure 8B) had maintained at least a 3% change of major strain relative to pretreatment. Similarly, after treatment of the jowls, a 5% change was observed in 25% of the patients 24 weeks post-implantation. Twelve weeks after barbed PDO suture placement in the lateral eyebrows (Figure 8C), maintenance of the effect was demonstrated by the high percentage of patients showing 2% to 5% major strain changes of the treated skin; a diminution of the effectiveness of the treatment was observed at Week 24 posttreatment.

Markerless tracking analysis featuring this 50-year-old female patient showing sagging jawline and treated with 3 Barb II (cannula 19G/90 mm) polydioxanone sutures on left lower jowl. Photographs show the patient at baseline and 6, 12, and 24 weeks after implantation. Suture implantation pattern (with permission of Croma-Pharma GmbH), analysis of skin movements, and vectors indicate intensity (see color scale) and direction of skin displacement (Figures 4-6) or major strain (Figure 7) compared with the baseline pretreatment photograph.

Markerless tracking analysis featuring this 39-year-old female patient presenting with mild sagging lateral eyebrows and treated with 3 Barb II (needle 23G/60 mm) polydioxanone sutures on the right brow. Photographs show the patient at baseline and 6, 12, and 24 weeks after implantation. Suture implantation pattern (with permission of Croma-Pharma GmbH), analysis of skin movements, and vectors indicate intensity (see color scale) and direction of skin displacement (Figures 4-6) or major strain (Figure 7) compared with the baseline pretreatment photograph.

Percentage of patients presenting with skin movements per treated region at 6, 12, and 24 weeks after treatment and relative to baseline as quantified by major strain parameter: (A) midface (cheeks), (B) jawline, and (C) eyebrows.

Nine patients (15%) experienced side effects of the treatment during the evaluation period. Most common were pain (in 6 patients, 10%) and hematoma (n = 5, 8%), all of which spontaneously resolved within 2 weeks. Other adverse device effects included short-lasting edema (n = 2, 3%), skin irregularities (n = 2, 3%), sensitized skin (n = 1, 2%), sensation of a strong pulling effect (n = 1, 2%), and asymmetry (n = 1, 2%) (Table 6). In a few instances, skin dimpling appeared immediately following treatment but were very transient effects and resolved easily following light massage of the involved area. No other adverse events were reported, apart from a treatment-unrelated nephrectomy because of kidney cancer in 1 patient.

| Type of AEs . | Patients presenting with AEs . | . |

|---|---|---|

| . | n . | % . |

| Pain | 6 | 10 |

| Hematoma | 5 | 8 |

| Edema | 2 | 3 |

| Skin irregularities | 2 | 3 |

| Sensitized skin | 1 | 2 |

| Strong pulling effect | 1 | 2 |

| Asymmetry | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 9 | 15 |

| Type of AEs . | Patients presenting with AEs . | . |

|---|---|---|

| . | n . | % . |

| Pain | 6 | 10 |

| Hematoma | 5 | 8 |

| Edema | 2 | 3 |

| Skin irregularities | 2 | 3 |

| Sensitized skin | 1 | 2 |

| Strong pulling effect | 1 | 2 |

| Asymmetry | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 9 | 15 |

AE, adverse event; PDO, polydioxanone.

| Type of AEs . | Patients presenting with AEs . | . |

|---|---|---|

| . | n . | % . |

| Pain | 6 | 10 |

| Hematoma | 5 | 8 |

| Edema | 2 | 3 |

| Skin irregularities | 2 | 3 |

| Sensitized skin | 1 | 2 |

| Strong pulling effect | 1 | 2 |

| Asymmetry | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 9 | 15 |

| Type of AEs . | Patients presenting with AEs . | . |

|---|---|---|

| . | n . | % . |

| Pain | 6 | 10 |

| Hematoma | 5 | 8 |

| Edema | 2 | 3 |

| Skin irregularities | 2 | 3 |

| Sensitized skin | 1 | 2 |

| Strong pulling effect | 1 | 2 |

| Asymmetry | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 9 | 15 |

AE, adverse event; PDO, polydioxanone.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first objective, measurable evaluation of barbed PDO sutures in a Caucasian population. Because no patient selection occurred during retrospective analysis of the chart review (except the exclusion of patients who had another aesthetical or surgical procedure in the same anatomical area within 24 weeks after PDO suture implantation), these results represent valuable real-world evidence of the benefits of the utilization of barbed PDO suture treatment in a dermatology practice. Various signs of aging, such as skin laxity or sagging of tissue, can be successfully corrected by utilizing incisionless subcutaneous implantation of barbed PDO sutures. The minimally invasive nature of the procedure, coupled with a palette of device models, allows the treating physician to achieve a diverse group of aesthetic corrections in a single treatment session. Barbed sutures are especially suitable when a substantial tissue elevation is needed, such as lifting of the cheeks, elevation of the midface for reducing nasolabial folds,22 recontouring of sagged jowls, or elevation of the lateral eyebrows. The choice of the subtype of barbed PDO sutures to be employed on a specific patient is based on both clinical judgement and experience of the treating physician. That said, for the correction of the midface (cheeks) or the jawline, a more substantial tissue lifting is needed as for the elevation of the lateral eyebrows; therefore, if shorter and thinner barbed PDO sutures are sufficient to achieve the correction of the eyebrows, longer and thicker barbed PDO sutures may be necessary to correct for aging signs on both other regions. For instance, in our study, 4 patients were treated with thicker or heavier barbed PDO sutures for the elevation of their jawline (bottom implantation, B3 cannula model, 19G/90 mm, 1-0 USP); the same thicker barbed PDO sutures also had been implanted in the midface (cheeks) of 16 additional patients for the correction of their sagging jawline because those patients were presenting heavier tissue as well. In the midface, the facial mimetic muscles are located much deeper than on the upper face; therefore, for lateral eyebrow elevation, the implantation of barbed PDO sutures over and following the forehead bone is much easier than on the midface (cheeks) or on the jawline.

The outcome of the PDO suture treatment can be observed immediately after the procedure, as acknowledged by most of the patients. Whereas the independent photographic reviewer had access to high-resolution photographs, the treating physician evaluated the patients live, which is usually a more sensitive measure of subtle clinical changes. Of course, evaluation of anatomical changes after suture implantation are much easier to see during 3D live assessment than on the 2D photographs presented here. Therefore, treatment outcomes have been additionally objectively measured through markerless tracking analysis and a statistical analysis of resulting data performed employing the statistical Wilcoxon signed rank test. As assessed by GAIS at 24 weeks posttreatment, the aesthetic improvement reached 80% to 100%, depending on the evaluator. The slight decrease in improvement observed at Week 24 compared with the other timepoints may be correlated with the PDO suture absorption by the body and concomitant collagen formation along the path of the implanted suture. The estimates made by the independent photographic reviewer were more conservative, probably because his appraisal was conducted on 2D photographs and not live in contrast to those performed by the treating physician and the patients in a 3D paradigm. Moreover, high patient satisfaction with treatment outcome, as well as their willingness to undergo the procedure again and to recommend it to others, is a strong argument in favor of the benefits of the aesthetic corrections achieved employing barbed PDO sutures.

The effectiveness of non-surgical suture lifting has been questioned in the literature,23-25 primarily because of lack of objective measurements. By contrast, in this study, treatment effectiveness was objectively determined utilizing a markerless tracking analysis, a novel and elegantly unbiased tool for precise quantification of skin movements.21 The significant increases (P ≤ 0.05) observed in posttreatment skin surface parameters were maintained up to 24 weeks after the procedure. These objective measurements confirmed the tightening of the midface tissue, the realignment of the jawline, or the lift of the lateral eyebrows, which had already been established by the visual observation of the pre- and posttreatment photographs. Six months post-implantation, many patients were still enjoying a quantitative aesthetic benefit (percentage of patients showing a 2%-5% major strain change related to baseline); this assessment therefore further validates the effectiveness of the barbed PDO device up to 24 weeks, as already shown through GAIS and patient satisfaction data. Skin lifting by PDO sutures also has been demonstrated in other studies employing various morphometric measurements.15,16,18 This study has shown that in most patients, some objective change from baseline was present up to 2 years after initial suture implantation.15 Older, male, or overweight patients often present with heavier facial tissue lacking skin laxity or elasticity; to achieve desired aesthetic correction in such patients, the utilization of higher-diameter barbed PDO sutures housed in a cannula appears to provide optimal correction.

Usually, the choice of a cannula or needle model is a matter of preference. Especially for physicians less experienced with the suture implantation technique, the utilization of cannulas instead of needles for suture insertion might be a safer option; however, the choice of cannula models available on the market is usually limited, because manufacturers’ portfolios mainly contain needle models. On the other hand, on a skin with acne scars, needle models should be preferably employed over cannula models.

To reduce the number of postprocedure complications, the utilization of the proper implantation technique for knotless PDO sutures is crucial in addition to an extensive knowledge of facial anatomy, especially the exact location of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system. In this instance, the adverse events rate (15%) and the types of complications observed in our patient population were not clinically concerning in contrast to recently published studies describing more severe complications with similar free-floating PDO sutures.22,26 The adverse events seen in the current study would seem to be more aligned with those reported in previous publications.4,15,16,18,27

Toxin and dermal filler treatments are usually employed to correct wrinkles and folds; because barbed PDO sutures allow for subtle tweaks and focus on anatomical areas not optimally targeted with both previously cited techniques, they are indicated in patients presenting with mild to moderate signs of aging and therefore in need for a slight lifting. Moreover, following PDO suture implantation, neocollagenesis along the suture path further supports the treatment effect over time. Additionally, dermal fillers might be employed following barbed PDO suture implantation as complimentary touch-up and fine-tuning of an overall facial rejuvenation process, as for the correction of slight volume deficit resulting from tissue lift.28 For instance, tightening of the tissue surrounding the nasolabial folds can be performed through barbed PDO suture implantation by elevating the midface (cheeks), often followed by a dermal filler injection to fill still-visible folds. Recently, Jeong et al published a case series involving 94 patients who received a multi-modal treatment—including barbed PDO suture lifting—for lower face correction; the authors concluded that high patient satisfaction and better outcomes can be achieved with this combined and individualized strategy.29 However, Suárez-Vega et al showed in a preclinical study that non-crosslinked hyaluronic acid is a powerful catalyzing agent for hydraulic degradation of PDO sutures; the utilization of dermal fillers for mesotherapy in conjunction with PDO sutures might therefore reduce the longevity of the suture lifting.30 Although the implanted barbed PDO sutures should be mostly absorbed by the surrounding tissues after 6 months,31,32 skin changes relative to baseline were still observed at Week 24. Shortly after implantation, a controlled inflammatory process begins, leading to the formation of collagen Type I along the path of the implanted suture.9,33 Over time, the PDO suture may gradually lose its tensile strength and then degrade, but its encapsulation by collagen may continue to support the weakened PDO suture in maintaining the fixation of the subdermal tissue in its elevated position.

Polygluconate is another absorbable material employed for barbed sutures; polygluconate barbed sutures have a high tensile strength based on the optimal distribution of tensile forces along the monofilament suture and demonstrated to be a safe and an effective method for tightening and lifting of aging face with mild and moderate sagging.34 Similarly, absorbable poly(L-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) sutures might be a safe and well-tolerated option for correction of ptosis in facial soft tissue.35 Our choice for barbed PDO sutures for this study was conducted by our long satisfying experience with this medical device in our practice over the past years.

PDO suture treatment also appears to improve skin appearance, making the overlying skin appear denser, brighter, and more elastic after the treatment.8,14,33 An increase in epidermal-, fibroblast-, keratinocyte-, and insulin-like growth factors, as well as transforming growth factor beta, has been demonstrated after PDO suture implantation in animal models.8,11 It is possible that the same effects occur in humans, contributing to overall treatment effect and remarkable patient satisfaction rates, as observed in this retrospective study and also reported by others.14-16,19,26,32

Our case series presents several potential limitations: (1) this is an open-label, unblinded, and non-randomized study with no sham control performed at a single study center; (2) 1 single criterion for patient selection was predefined; (3) treatment was limited to barbed PDO sutures; and (4) there was no assessment of long-lasting effect over 6 months of follow-up. Indeed, positive results achieved with barbed PDO suture implantation may last up to 6 months and the procedure may thus need to be repeated to maintain the desired effect.36-38

Conclusions

Skin lifting with incisionless barbed PDO sutures is a safe and effective treatment option for patients presenting with mild to moderate symptoms of facial aging. Satisfactory aesthetic results can be obtained with the proper selection of patients presenting with mild to moderate signs of aging; additional critical factors are the choice of the appropriate barbed suture size and introduction technique as well as their careful anatomic positioning in the targeted treatment areas, coupled with a knowledge of skin properties and realistic assessment of the achievable degree of correction. Side effects are typically mild and short-lasting. Although a minimal risk of asymmetry exists, this can be further minimized by using proper implantation technique.

In conclusion, compared with more invasive procedures, the utilization of free-floating PDO sutures is associated with high levels of patient satisfaction, clinically demonstrable aesthetic effects lasting for up to 6 months, and a low complication rate; these outcomes have been further supported here by statistically significant objective quantitative data resulting from a markerless tracking analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Ira Lawrence and Dr Zrinka Ivezic-Schoenfeld for very helpful discussions and input during manuscript preparation.

Disclosures

Dr Lorenc is a consultant, Dr Boulmé is a former employee, and Dr Preibisz is a former consultant for Croma-Pharma GmbH (Leobendorf, Niederösterreich, Austria).

Funding

The analysis of the pictures (markerless tracking analysis) performed by Canfield Scientific, Inc. (Parsippany, NJ, USA) was supported by Croma-Pharma GmbH (Leobendorf, Austria). Grand Aespio Inc. (Seoul, Korea) provided non-commercial PDO suture samples.

References

Author notes

Dr Preibisz is a dermatologist in private practice in Warsaw, Poland.

Dr Boulmé is a principal partner at Cilas, Scientific and Medical Writing, Vienna, Austria.

Dr Lorenc is a plastic surgeon in private practice in New York, NY, USA