-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sze Ng, Emily Parker, Andrea Pusic, Gillian Farrell, Colin Moore, Elisabeth Elder, Rodney D Cooter, John McNeil, Ingrid Hopper, Lessons Learned in Implementing Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) in the Australian Breast Device Registry (ABDR), Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 42, Issue 1, January 2022, Pages 31–37, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjaa376

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The Australian Breast Device Registry (ABDR) is a clinical quality registry which utilizes both surgical data and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) to understand device performance. The ABDR is the first national breast device registry utilizing the BREAST-Q Implant Surveillance module to conduct PROMs via text messaging as the primary method of contact for most patients. ABDR PROMs are structured upon a successful acceptability and feasibility study and a pilot study.

This aim of this paper was to examine the challenges we faced and consider how lessons learned in implementing PROMs might inform future registry studies and interventions.

We tracked the number of completed follow-ups and documented feedback between October 2017 and December 2018 from various stakeholders, including sites, surgeons, and patients.

In total, 10,617 patients were contacted: 59% of breast augmentation and 77% breast reconstruction patients responded to our PROMs survey. We encountered challenges and developed solutions to overcome several key issues, including database setup; follow-up contact methods; ethics; education of surgeons and patients; associated costs; and ongoing evaluation and modification. The strategies we devised to address these challenges included drawing on experiences from previous studies, greater communication with sites and surgeons, and having the flexibility to improve and modify our PROMs.

The ABDR PROMs experience and lessons learned can inform a growing number of registries seeking to conduct PROMs. We describe our approach, obstacles encountered, and strategies to increase patient participation. As more breast device registries worldwide adopt PROMs, data harmonization is crucial to better understand patient outcomes and device performance.

The Australian Breast Device Registry (ABDR) is a national breast device clinical quality registry (CQR) which commenced in 2015. The ABDR uses the opt-out consent approach to collect breast device data from all eligible patients, provided that their surgeons and hospitals are participating in the registry. The ABDR is housed within the Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine at Monash University and funding is provided by the Commonwealth Government.1 The ABDR has been growing steadily in sites, surgeons, and patient numbers.2 According to the ABDR 2018 Annual Report, there were 514 surgeons participating across 280 sites and 37,673 patients in the database.2 As a CQR, it is designed to monitor the long-term safety and performance of breast devices, identify and report on possible trends and complications associated with breast device surgery, and identify best surgical practice and optimal patient health outcomes.3

Breast implants are generally considered safe to use, although links to long-term health outcomes are unclear.4 Recently, studies linking textured breast implants to breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma resulted in action by a number of regulators,5 including the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) of Australia, which recalled all unused breast implants and tissue expanders of a number of brands of textured implants sold in Australia.6 Several countries worldwide are in the process of establishing breast implant registries to further understand the long-term health outcomes of breast implants.1,7,8 Monitoring of breast device performance by the ABDR is independent of industry. The ABDR provides data on performance of breast devices to the TGA. Manufacturers also provide data on adverse events to the TGA.

Traditionally, outcome measures for breast implant surgeries have been based around short and long-term surgical outcomes, such as implant revision surgery or implant removal.9 More recently there has been a focus on patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in healthcare generally.10 PROMs have been increasingly utilized in a number of registry settings, including device registries such as orthopedic registries and disease-specific registries such as prostate cancer registries, as healthcare transitions to more patient-centred and value-based approaches that emphasize quality improvement.11-14

The ABDR seeks to utilize PROMs to understand device performance at a time beyond regular surgical clinical follow-up and as a potential early warning signal of an underperforming device.15 PROMs have also been endorsed as a clinical quality indicator to enable breast device registries to benchmark care in patients undergoing breast device surgery.16 Data collected by the ABDR will help safeguard the health of people undergoing breast device surgery, assist patients and surgeons make more informed choices about breast devices, and achieve the best surgical outcomes.

In this paper, we examine the challenges we encountered planning, implementing, and collecting PROMs data from our registry patients on a national level in Australia.

METHODS

The ABDR PROMs Study Design

We started planning for ABDR PROMs roll out to all patients within the registry in August 201715 and we reflect upon our experiences of implementing PROMs nationally in the period from October 2017 to December 2018. We built on our earlier acceptability and feasibility study, which found the 5-question Breast-Q Implant Surveillance module (BREAST-Q IS) to be generally acceptable among patients and surgeons, and our pilot study with 76% total response rate (71.2% breast augmentation and 83.5% breast reconstruction).

We defined who would be eligible to receive PROMs with the following inclusion criteria: patients registered on the ABDR who had breast device surgery 1, 2, and 5 years ago, had not opted out of the registry or follow-up, and were aged over 18 years old at the time of follow-up. Exclusion criteria included patients who received a recent replacement or removal of a breast device, patients who live in the European Union (due to the General Data Protection Regulation),17 or who have no active contact details.

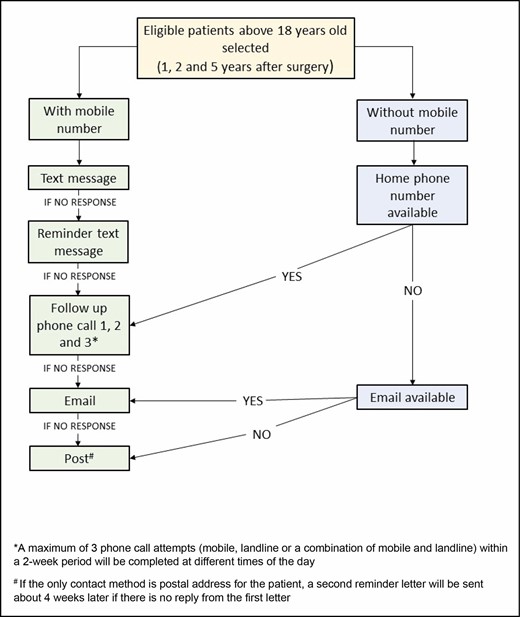

We then divided eligible patients into “Reconstruction” and “Cosmetic Augmentation” procedure cohorts. Patients were further filtered by primary method of contact (in order of priority): mobile phone, landline, email, and post. The patient engagement procedure was by order of available contact details from mobile phone, landline, email, and post (Figure 1).

The Australian Breast Device Registry patient-reported outcome measures patient engagement strategy by order of available contact details from mobile phone, landline, email, to post.

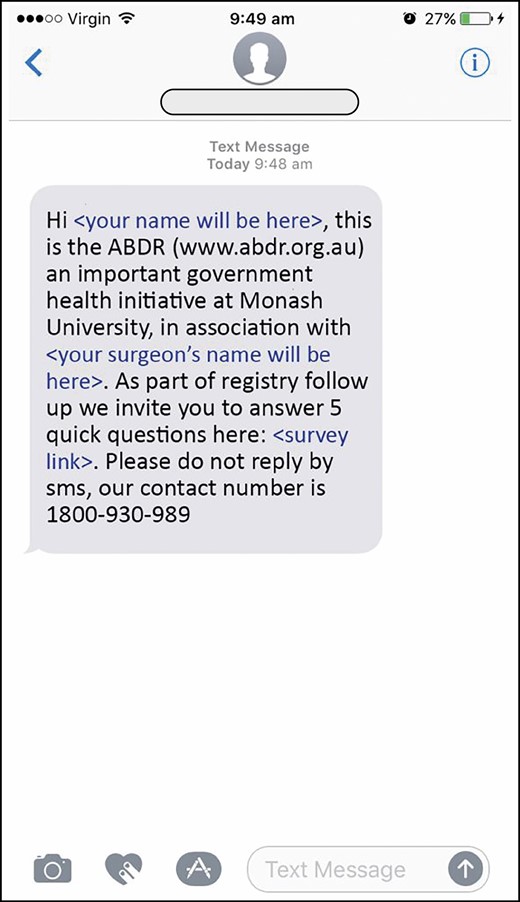

Similar to our pilot study, we used the Qualtrics platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) to send an invitational text message to mobile phone numbers. The message contains a unique web link which can be opened on a mobile phone (Figure 2); this link opens a webpage with an introduction to the ABDR study and the BREAST-Q IS. Patients answer the survey questions directly and submit their responses to the ABDR.

The Australian Breast Device Registry patient-reported outcome measures invitational text message: an example of the text message sent to eligible patients.

As seen in our patient engagement strategy flowchart, patients were given a number of opportunities to either complete the PROMs follow-up by means of text messaging, phone call, email, or post. At the time of PROMs collection, patients were asked their preferred contact method, and could elect for the survey to be sent by a different method than the primary contact method. Patients were able to opt out of follow-up or opt out of the registry completely at any time point.

The project was approved by the Alfred Human Research Ethics Committee (566/16) and all associated human research and ethics committees (HRECs).

RESULTS

Between October 2017 and December 2018, we contacted a total of 10,617 patients (9204 breast augmentation and 1413 breast reconstruction).2 A total of 59% of breast augmentation and 77% breast reconstruction patients responded to our PROMs survey.2

IMPLEMENTATION ISSUES FOR A NATIONWIDE PROMS PROGRAM FOR BREAST DEVICES

Establishing a Clear Objective

The initial plan with the PROMs was to identify a poorly performing device earlier than would be identified through revision surgery, particularly in light of revision surgery for breast implants being elective in nature. The feasibility and acceptability study indicated that surgeons viewed the questions as likely to indicate the need for surgery, rather than necessarily a problem with the device itself.18 It was also clear that separating device performance from surgeon performance would be difficult. We recognized that one role of the PROMs study was to assess device performance, and secondarily they could also be used to assess surgeon performance. Indeed, PROMs have been endorsed in a Delphi study by the ABDR as one of 3 quality indicators to assess the quality of breast device surgery.16 The PROMs data were also recognized as a signal of a potential problem with a device. Under these circumstances, it would be expected that identification of a safety signal from PROMs would lead to a full investigation by the regulator.

Database

To enable efficient tracking of PROMs, a PROMs database linked to the ABDR database was crucial. We designed our database based on our experience tracking patients during the pilot study. It needed to accurately identify patients’ corresponding site and ethics committee, age, years since surgery, and available contact details. We also needed the ability to view patients’ breast device history and confirm any discrepancies, in particular missed revision surgery. We also needed to ensure that patients received follow-up according to our patient engagement procedure, and therefore the database needed to track the date of each contact attempt by text message, phone, email, or post. The database also needed to record patient responses.

Currently our PROMs database extracts eligible patients who have had surgery 1, 2, and 5 years prior to a selected month, and from the generated list, we identify all patients whom we need to contact for the month. The database can also filter patients by contact method so the process can start depending on where they fall under the patient engagement procedure. It is important to note that a well-designed database has to allow for enhancement and flexibility.

Follow-up Contact Methods

In order to minimize selection bias and ensure generalizability, a minimum response rate of 60% has been recommended by the International Society of Arthroplasty Registries PROMs Working Group and the Journal of the American Medical Association.19 We explored different methods to collect PROMs data, based on the recommendation by Hoque et al13 that to achieve a sufficiently high PROMs response rate, a multimodal data collection approach is needed rather than a single-mode approach. Text message was selected as the most economic means for first contacting the large number of patients, and also suitable for the relatively young and mobile population of patients undergoing breast device surgery.

For the survey platform, our requirement was that it would be simple to use, comply with privacy and data security requirements, and be cost effective. We selected Qualtrics, which is the research survey platform that Monash University uses. The major advantages of this platform include that text messages are sent from within Australia so there is no issue with transborder data flow, data are stored within Australia, and it is compliant with Australian privacy legislation.

In order to understand the implications of contacting patients via the Qualtrics platform, we asked patients how they would feel about receiving a survey via text messaging,18 and completed a pilot study that used text messaging as the primary contact method.15 Conscious of patients’ privacy and the importance of confidentiality, we crafted an invitational text message that was designed to catch the attention of the patient by including the surgeon’s name, but not be obviously associated with breast device surgery. This wording was amended based on feedback from our pilot study and by our steering and management committees.

Our telephone follow-ups were performed by trained personnel, and we developed documents including a telephone script, frequently asked questions, and instructions for handling difficult calls. Supervisors were available to debrief or assist in the event of difficult calls. In light of regulatory action by the TGA in 2019 leading to recalls of a number of breast devices, our staff were also trained to give patients appropriate answers about the evolving situation, which included referring patients to the Breast Implant Hub at the TGA website for further information while maintaining patient privacy.20

Ethics Challenges

When planning for the national roll-out of our PROMs program in 2017, acquiring the requisite ethics approvals presented a major challenge. Because the ABDR is a national registry, we needed to obtain approval from 17 separate HRECs, as well as obtain governance approval for each site. This was a challenging task.

The initial ethics approval was obtained from our primary HREC, which is Alfred Health. Their concerns included text messaging not being a common method of contact for registries, and the number of contacts and the multimodal approach (test messaging, phone, email and mail) that we proposed. We addressed the concerns of the ethics committee at a face-to-face meeting and discussed our project in detail. We shared with the ethics committee our experiences from the first 2 studies,15,18 as well as other research studies showing that survey completions by telephone follow-up were higher than email and postal follow-up (80% vs 24% and 34%).21 We successfully obtained ethics approval to commence the PROMs program nationally with a minor amendment to the wording in our PROMs contact protocol. Other HRECs approved shortly thereafter.

Educating Surgeons and Patients on PROMs

At the commencement of the national roll-out of the ABDR in 2015, we undertook a series of showcases in each state across the country to educate surgeons and answer questions. As part of this, we discussed our plan to collect PROMs. When PROMs collection commenced in 2017, we notified all surgeons participating in the ABDR by email and e-newsletter. These newsletters included highlights for a few key factors that could improve our PROMs follow-up rate. First, the importance of complete contact details for patients, as email addresses are not included on patient identification stickers from hospitals. Second, our experience was that patients felt more comfortable being contacted directly if they had been informed about ABDR PROMs follow-up before having breast device surgery. Third, that surgeons informed their patients of the importance of keeping the ABDR updated of any change in their contact details.

A major challenge to utilizing text messaging as a method to collect PROMs was that some patients interpreted the text message as a spam message. In order to ensure patients were confident enough to complete the PROMs by receiving a text message and clicking on the survey link in the message, we included their surgeon’s name and our ABDR website address in the text message. At the same time, we included on our ABDR website’s front page (www.abdr.org.au) details about how text messaging is being used to collect PROMs details on breast implants. A number of patients contacted their clinic concerned about receiving a text message relating to their breast device, and in turn we received some enquiries from surgeons. This highlighted the importance of reminding clinic receptions, who are usually the first point of contact for patients, about ABDR PROMs. We also amended the Participant Explanatory Statement and the Surgeon Agreement to highlight that PROMs would be collected.

Ongoing Evaluation and Modification

Our PROMs tool, the BREAST-Q IS, was newly created for the ABDR based on the larger validated BREAST-Q.18 These 5 questions were selected through an exploratory analysis on the BREAST-Q dataset and were considered to be most sensitive to device issues and performance, adverse events, and most likely to predict the need for breast device revision surgery.15 Further validation of the BREAST-Q IS continues, with test-retest completed,22 and other assessments ongoing. The ABDR PROMs pilot study indicated that patients would like to add specific symptoms that they were experiencing that were not part of the BREAST-Q IS questions. We included an open-ended question at the end of the PROMs to allow patients to document any symptoms or comments which will be analysed at a later date. These comments will allow us to determine if we need to revise our BREAST-Q IS questions, and this flexibility allows us to respond to emerging health issues. The ABDR also meets regularly with surgeons, patient groups, and industry to keep stakeholders up to date and receive feedback, and also with the management and steering committees to discuss the progress of data collection and data analysis.

Costs

Costs are a key concern when collecting PROMs in the registry setting. Currently the registry collects PROMs across the entire ABDR patient population, because when PROMs are used for quality improvement, it is recommended that all patients should be assessed, as opposed to a sample population.19 We have estimated our costs of text messages as AU$0.21 per text message, AU$3.43 per phone call, and AU$1.50 per posted survey. According to our calculations, the cost is AU$9.02 per completed PROMs patient. In order to curtail our costs, in late 2019, we decreased the number of telephone contacts from 3 phone calls to 1 for those with mobile numbers, and only 2 landline calls if no mobile phone number was available. During their first PROMs follow-up, we requested patients to update their contact details to include email addresses to allow another point of contact for subsequent PROMs contacts.

DISCUSSION

We have outlined some of the challenges we encountered when implementing PROMS in a national breast device registry. It is important to consider whether PROMs in a breast device registry are worthwhile. PROMs in the ABDR are costly and require substantial human resources for direct contact with patients. This was illustrated recently in a study by Pronk et al23 which showed that a cost increase from €4 to €10 per surgical procedure between minimal effort (digital online automated PROMs collection system) and maximal effort (combined automated system and manual collection) groups was needed to improve response rates from 44% to 76%. However, PROMs offer a unique opportunity to identify a safety signal earlier than by waiting for revision surgery to occur, thereby allowing regulators to move quickly to assess a potentially underperforming device and protect patients. The collection of data on a national level with a standardized validated PROMs tool allows us to provide a systematic evaluation of the experience and safety of breast devices. Importantly PROMs allow us to understand breast device performance from the end-user perspective, rather than the clinician perspective. If patients are concerned about their implant, they are advised to contact their doctor to arrange an appointment. Currently for the ABDR, reporting from surgeons is voluntary, and there is no mandatory tracking of implants inserted or revised overseas. PROMs have allowed us to identify surgeries, including device explants, reported to us by patients in their PROMS response, that had not been reported to the registry. These data on revisions and explants are crucial to further our understanding of breast device performance. PROMs also serve to remind patients and clinicians about the importance of the ongoing assessment of breast device safety.

Future Direction of PROMs in the ABDR

In order to achieve high response rates across a broad range of patients, it is important to make patients aware of how their data will be used.24 Individual PROMs results are currently not made available in order to maintain privacy and confidentiality. We have commenced reporting of the aggregate PROMs results in our annual report,2 and will further undertake PROMs analysis by device characteristics and brand; we will publish these findings in due course. PROMs data are available on request for surgeons for their patients group if PROMs data are sufficient in number that patients cannot be individually identified. This is determined on a case-by-case basis, but a minimum of 20 responses is considered sufficient for patient anonymity. Surgeons can use these data to gain insights on their own results, or compare them against a national average. In the future, PROMS may also help drive quality improvement by benchmarking the quality of providers,25 however, at this stage benchmarking between providers or sites will not be undertaken until adequate protection of the data can be assured.26 Aggregate PROMs results will also form part of the safety assessments for the national regulator, and for device companies to understand the performance of their product, which can then be incorporated into decisions in the future by patients and clinicians about which breast device is most appropriate.

International standardization is also an important consideration when collecting PROMs. ABDR is part of the International Collaboration of Breast Registry Activities, an organisation to establish international standardization and harmonization of breast device registries.27 This is consistent with a literature review identifying international standardization as an important subtheme when setting up PROMs.24 It is also vital that a universal system can be designed to ensure easy adoption by countries wanting to join.24 At present, Australia is the only country to use the BREAST-Q IS, but other registries, including the US National Breast Implant Registry, plan to adopt it. This would allow international benchmarking to take place. Currently Sweden uses a similar PROMs which was locally developed.

The limitation of this study include that it reflects mostly the implementation period with the PROMs.

CONCLUSIONS

We outline here a number of lessons learnt and our experience when rolling out PROMs on a national scale in Australia. To implement a successful PROMs program within a clinical quality registry, we recommend running a feasibility and acceptability study, and a pilot study, identify a clear objective, establish sustainable resources, agree upon follow-up methods, and maintain communication and collaboration between stakeholders. Utilizing a standardized valid PROMs tool within a robust CQR is crucial to performing systematic postmarket evaluation of breast implants. A focus on international standardization of data collected will allow data harmonization, and a larger dataset to analyze and gain a better understanding of patient outcomes. More work is needed to develop cost-effective methods of engaging patients to deliver high response rates.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

Dr Ng, Dr Parker, Dr Farrell, Dr Cooter, Dr Elder, Dr Moore, and Dr McNeil have nothing to declare. Dr Pusic is co-developer of the BREAST-Q which is owned by Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; she receives a portion of licensing fees (royalty payments) when the BREAST-Q is used in industry-sponsored clinical trials. Dr Hopper is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council fellowship. Funding for the ABDR PROMs Study is provided by the Australian Commonwealth Department of Health.

Acknowledgments

The ABDR is grateful for funding received from the Australian Commonwealth Government. Dr Hopper is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council fellowship.

REFERENCES