-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Luke J Grome, Ross M Reul, Nikhil Agrawal, Amjed Abu-Ghname, Sebastian Winocour, Edward P Buchanan, Renata S Maricevich, Edward M Reece, A Systematic Review of Wellness in Plastic Surgery Training, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 41, Issue 8, August 2021, Pages 969–977, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjaa185

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Physician and resident wellness has been increasingly emphasized as a means of improving patient outcomes and preventing physician burnout. Few studies have been performed with a focus on wellness in plastic surgery training.

The aim of this study was to systematically review what literature exists on the topic of wellness in plastic surgery training and critically appraise it.

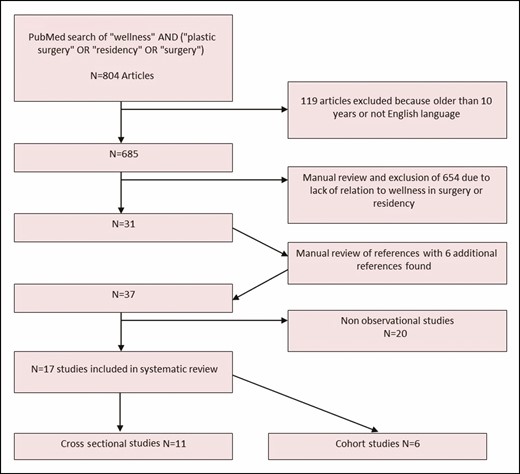

A PubMed search was performed to identify journal articles related to wellness in plastic surgery residency. Seventeen studies (6 cohort and 11 cross-sectional) met inclusion criteria and were appraised with the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOQAS) to determine the quality of the studies based on selection, comparability, and outcome metrics.

Critical assessment showed that the studies were highly variable in focus. Overall, the quality of the data was low, with an average NOQAS score of 4.1. Only 2 studies focused on plastic surgery residents, examining work hours and social wellness, respectively; they were awarded NOQAS scores of 3 and 4 out of 10.

The results of this systematic review suggest that little research has been devoted to wellness in surgery training, especially in regard to plastic surgery residents, and what research that has been performed is of relatively low quality. The available research suggests a relatively high prevalence of burnout among plastic surgery residents. Evidence suggests some organization-level interventions to improve trainee wellness. Because outcomes-based data on the effects of such interventions are particularly lacking, further investigation is warranted.

Wellness in medical training and its role in physician health, program satisfaction, attrition, and patient outcomes has become a point of focus over the past several years, especially as it relates to burnout. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) now requires residency programs to incorporate wellness into their curriculum with the goal of instilling the values of wellness and resilience as well as burnout reduction in their trainees.1 As of 2017, the ACGME has included resident psychological, emotional, and physical well-being into their Common Program Requirements for accreditation. That same year, the ACGME Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program released its first report, emphasizing areas such as work-life balance, fatigue, and burnout.

Wellness encompasses both physical and mental wellbeing, and “goes beyond merely the absence of distress and includes being challenged, thriving, and achieving success in various aspects of personal and professional life.” 1 Often-mentioned features of individual wellness include sleep, exercise, diet, and interpersonal relationships.

The purpose of this study was to systemically review the literature on physician and resident wellness as it applies to plastic surgery and describe our findings.

METHODS

Literature Search Strategy

A PubMed search was performed to identify studies pertaining to wellness as it relates to plastic surgery residency (L.J.G.; October 2019). The search terms “wellness” AND (“plastic surgery” OR “residency” OR “surgery”) were used in our search with the goal of answering the following questions: How is wellness defined in plastic surgery and plastic surgery training? What are the main combatants to plastic surgery resident/physician wellness? What is the attrition in plastic surgery training? How can resident wellness and attrition be improved? The search was limited to human studies published in the English language within the past 10 years. The reference list of each retrieved article was manually reviewed to capture other potentially relevant publications. The study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Appendix).

Selection of Articles

Two authors (R.M.R. and L.J.G.) independently assessed studies for eligibility. Uncertainties and discrepancies were discussed and resolved by these 2 authors, who agreed on 100% of the studies selected for inclusion.

Inclusion Criteria

Publications assessing wellness in plastic surgery

Publications assessing wellness and/or attrition in surgical residency

Publications assessing tools to improve wellness in surgical residency

Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded from this review if their topic was not related to wellness in one of the following fields: plastic surgery, residency, or surgery, or if it did not address 1 of our questions above. Non-English language articles and articles more than 10 years old were excluded. Animal studies, review articles, case reports, expert opinions, and duplicate records were excluded from analysis. Expert opinions and case reports were included in the discussion as they provide valuable insight to this relatively unexplored topic.

Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed by 1 author (R.M.R.) and verified independently by 2 authors (L.J.G. and N.A.). Each reviewer assessed whether each publication reported data on the following: (1) country; (2) study design; (3) sample size; (4) type of intervention; (5) duration of follow-up; (6) wellness, burnout, or attrition as primary study outcome; (7) outcome measures; and (8) level of evidence.

Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (R.M.R. and L.J.G.) independently appraised each publication according to study design. None of the studies found in our review of the literature were randomized trials. Nonrandomized observational studies were evaluated utilizing the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOQAS) to appraise the validity of each.2,3 Discrepancies between the 2 reviewers were addressed by a joint re-evaluation of the original article. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) Evidence Rating Scale for Therapeutic Studies was used to classify the included studies according to the level of evidence.4 Meta-analysis was not conducted due to the heterogeneity of the included studies in terms of design and outcome assessment.

RESULTS

Included Studies

Our PubMed search resulted in 804 articles. Figure 1 outlines how studies were selected for inclusion within the systematic review. Non-English-language articles and articles older than 10 years were excluded first. The abstracts of the remaining 685 articles were screened manually, and 654 articles were excluded according to our exclusion criteria. In the remaining 31 articles, review of the bibliography resulted in an additional 6 relevant references.5-41 Seventeen of the 37 articles were cohort or cross-sectional studies and thus met the criteria to be included in our systematic review.

Study Characteristics

The characteristics of the studies included in our systematic review can be found in Table 1. All studies were published after 2011, with 82% of studies being published between 2017 and 2019. All studies bar one originated from the United States. Seventeen studies were observational in design, 6 of which were cohort studies and 11 were cross-sectional studies. Of the cohort studies, duration of follow-up ranged from 12 to 52 weeks. Most cohort wellness interventions were well received but few quantitative outcomes data were reported, and the study sample sizes were low (n = 8-188). The number of respondents of the cross-sectional studies ranged from 7 to 7917. Two of the studies focused primarily on plastic surgery residents. All studies examined burnout or wellness as a primary outcome. The study results were highly variable due to differing study populations, methodology, and primary outcomes. Wellness and/or burnout were assessed in a variety of manners, and the factors associated with each were equally inconsistent. Overall, both intrinsic and extrinsic factors were implicated in unfavorable physician wellbeing.

| Study . | Country . | Study design . | Sample size . | Type of intervention . | Duration of follow-up . | Primary study outcome . | Outcome measures . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggarwal et al12 | US | Cohort | 188 residents | Wellness lectures | 12 weeks | Wellness | Participation |

| Baiu et al13 | US | Cohort | 18 residents | Care packages | NA | Wellness | Subjective responses |

| Bingmer et al15 | US | Cohort | 32 residents | Formal mentorship program | 52 weeks | Resident faculty relationship, wellness | Likert-type scale |

| Deshauer et al18 | US | Cross-sectional | 17 participants | Interviews | NA | Wellness | Subjective |

| Golub et al19 | US/UK | Cross-sectional | 684 residents, attendings and other | Survey | NA | Burnout | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Jackson et al22 | US | Cross-sectional | 1904 residents | Survey | NA | Wellness, burnout, PTSD | Maslach Burnout Inventory, primary care PTSD screen, job in general scale, Likert-type scale |

| Marek et al24 | US | Cohort | 28 residents | Activity tracker wristbands | 16 weeks | Burnout, wellness | Activity tracker and self-reported burnout |

| McInnes et al26 | Canada | Cross-sectional | 80 residents, 10 program directors | Survey | NA | Wellness | Objective and subjective survey |

| O’Brien et al31 | US | Cross-sectional | 47 plastic surgery program directors | Survey | NA | Wellness | Objective survey |

| Qureshi et al5 | US | Cross-sectional | 1691 surgeons | Survey | NA | Burnout | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Shanafelt et al33 | US | Cross-sectional | 7917 surgeons | Survey | NA | Burnout, wellness | Nonvalidated internal scale |

| Spiotta et al35 | US | Cohort | 8 residents | Wellness program | 52 weeks | Wellness | Personal health questionnaire depression scale, generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale, quality of life scale, Epworth Sleepiness Scale |

| Stack et al36 | US | Cross-sectional | 804 residents | Survey | NA | Burnout | Self-reported and modified Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Strauss et al37 | US | Cross-sectional | 62 residents | Survey | NA | Burnout | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Verheyden et al7 | US | Cross-sectional | 59 residency programs | Survey | NA | Wellness | Nonvalidated internal scale |

| Weis et al39 | US | Cohort | 103 residents | “Fuel gauge” self-assessment | 51 weeks | Wellness, burnout | Subjective scale |

| Wolfe et al40 | US | Cross-sectional | 7 residency programs | Survey | N/A | Wellness | Subjective |

| Study . | Country . | Study design . | Sample size . | Type of intervention . | Duration of follow-up . | Primary study outcome . | Outcome measures . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggarwal et al12 | US | Cohort | 188 residents | Wellness lectures | 12 weeks | Wellness | Participation |

| Baiu et al13 | US | Cohort | 18 residents | Care packages | NA | Wellness | Subjective responses |

| Bingmer et al15 | US | Cohort | 32 residents | Formal mentorship program | 52 weeks | Resident faculty relationship, wellness | Likert-type scale |

| Deshauer et al18 | US | Cross-sectional | 17 participants | Interviews | NA | Wellness | Subjective |

| Golub et al19 | US/UK | Cross-sectional | 684 residents, attendings and other | Survey | NA | Burnout | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Jackson et al22 | US | Cross-sectional | 1904 residents | Survey | NA | Wellness, burnout, PTSD | Maslach Burnout Inventory, primary care PTSD screen, job in general scale, Likert-type scale |

| Marek et al24 | US | Cohort | 28 residents | Activity tracker wristbands | 16 weeks | Burnout, wellness | Activity tracker and self-reported burnout |

| McInnes et al26 | Canada | Cross-sectional | 80 residents, 10 program directors | Survey | NA | Wellness | Objective and subjective survey |

| O’Brien et al31 | US | Cross-sectional | 47 plastic surgery program directors | Survey | NA | Wellness | Objective survey |

| Qureshi et al5 | US | Cross-sectional | 1691 surgeons | Survey | NA | Burnout | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Shanafelt et al33 | US | Cross-sectional | 7917 surgeons | Survey | NA | Burnout, wellness | Nonvalidated internal scale |

| Spiotta et al35 | US | Cohort | 8 residents | Wellness program | 52 weeks | Wellness | Personal health questionnaire depression scale, generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale, quality of life scale, Epworth Sleepiness Scale |

| Stack et al36 | US | Cross-sectional | 804 residents | Survey | NA | Burnout | Self-reported and modified Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Strauss et al37 | US | Cross-sectional | 62 residents | Survey | NA | Burnout | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Verheyden et al7 | US | Cross-sectional | 59 residency programs | Survey | NA | Wellness | Nonvalidated internal scale |

| Weis et al39 | US | Cohort | 103 residents | “Fuel gauge” self-assessment | 51 weeks | Wellness, burnout | Subjective scale |

| Wolfe et al40 | US | Cross-sectional | 7 residency programs | Survey | N/A | Wellness | Subjective |

NA, not available; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

| Study . | Country . | Study design . | Sample size . | Type of intervention . | Duration of follow-up . | Primary study outcome . | Outcome measures . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggarwal et al12 | US | Cohort | 188 residents | Wellness lectures | 12 weeks | Wellness | Participation |

| Baiu et al13 | US | Cohort | 18 residents | Care packages | NA | Wellness | Subjective responses |

| Bingmer et al15 | US | Cohort | 32 residents | Formal mentorship program | 52 weeks | Resident faculty relationship, wellness | Likert-type scale |

| Deshauer et al18 | US | Cross-sectional | 17 participants | Interviews | NA | Wellness | Subjective |

| Golub et al19 | US/UK | Cross-sectional | 684 residents, attendings and other | Survey | NA | Burnout | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Jackson et al22 | US | Cross-sectional | 1904 residents | Survey | NA | Wellness, burnout, PTSD | Maslach Burnout Inventory, primary care PTSD screen, job in general scale, Likert-type scale |

| Marek et al24 | US | Cohort | 28 residents | Activity tracker wristbands | 16 weeks | Burnout, wellness | Activity tracker and self-reported burnout |

| McInnes et al26 | Canada | Cross-sectional | 80 residents, 10 program directors | Survey | NA | Wellness | Objective and subjective survey |

| O’Brien et al31 | US | Cross-sectional | 47 plastic surgery program directors | Survey | NA | Wellness | Objective survey |

| Qureshi et al5 | US | Cross-sectional | 1691 surgeons | Survey | NA | Burnout | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Shanafelt et al33 | US | Cross-sectional | 7917 surgeons | Survey | NA | Burnout, wellness | Nonvalidated internal scale |

| Spiotta et al35 | US | Cohort | 8 residents | Wellness program | 52 weeks | Wellness | Personal health questionnaire depression scale, generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale, quality of life scale, Epworth Sleepiness Scale |

| Stack et al36 | US | Cross-sectional | 804 residents | Survey | NA | Burnout | Self-reported and modified Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Strauss et al37 | US | Cross-sectional | 62 residents | Survey | NA | Burnout | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Verheyden et al7 | US | Cross-sectional | 59 residency programs | Survey | NA | Wellness | Nonvalidated internal scale |

| Weis et al39 | US | Cohort | 103 residents | “Fuel gauge” self-assessment | 51 weeks | Wellness, burnout | Subjective scale |

| Wolfe et al40 | US | Cross-sectional | 7 residency programs | Survey | N/A | Wellness | Subjective |

| Study . | Country . | Study design . | Sample size . | Type of intervention . | Duration of follow-up . | Primary study outcome . | Outcome measures . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggarwal et al12 | US | Cohort | 188 residents | Wellness lectures | 12 weeks | Wellness | Participation |

| Baiu et al13 | US | Cohort | 18 residents | Care packages | NA | Wellness | Subjective responses |

| Bingmer et al15 | US | Cohort | 32 residents | Formal mentorship program | 52 weeks | Resident faculty relationship, wellness | Likert-type scale |

| Deshauer et al18 | US | Cross-sectional | 17 participants | Interviews | NA | Wellness | Subjective |

| Golub et al19 | US/UK | Cross-sectional | 684 residents, attendings and other | Survey | NA | Burnout | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Jackson et al22 | US | Cross-sectional | 1904 residents | Survey | NA | Wellness, burnout, PTSD | Maslach Burnout Inventory, primary care PTSD screen, job in general scale, Likert-type scale |

| Marek et al24 | US | Cohort | 28 residents | Activity tracker wristbands | 16 weeks | Burnout, wellness | Activity tracker and self-reported burnout |

| McInnes et al26 | Canada | Cross-sectional | 80 residents, 10 program directors | Survey | NA | Wellness | Objective and subjective survey |

| O’Brien et al31 | US | Cross-sectional | 47 plastic surgery program directors | Survey | NA | Wellness | Objective survey |

| Qureshi et al5 | US | Cross-sectional | 1691 surgeons | Survey | NA | Burnout | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Shanafelt et al33 | US | Cross-sectional | 7917 surgeons | Survey | NA | Burnout, wellness | Nonvalidated internal scale |

| Spiotta et al35 | US | Cohort | 8 residents | Wellness program | 52 weeks | Wellness | Personal health questionnaire depression scale, generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale, quality of life scale, Epworth Sleepiness Scale |

| Stack et al36 | US | Cross-sectional | 804 residents | Survey | NA | Burnout | Self-reported and modified Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Strauss et al37 | US | Cross-sectional | 62 residents | Survey | NA | Burnout | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Verheyden et al7 | US | Cross-sectional | 59 residency programs | Survey | NA | Wellness | Nonvalidated internal scale |

| Weis et al39 | US | Cohort | 103 residents | “Fuel gauge” self-assessment | 51 weeks | Wellness, burnout | Subjective scale |

| Wolfe et al40 | US | Cross-sectional | 7 residency programs | Survey | N/A | Wellness | Subjective |

NA, not available; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Data Quality

The NOQAS was used to assess the quality of each publication based on its high content validity and interrater reliability. Quality assessments can be found in Table 2. The authors assigned scores with an interrater reliability of 94.1%. These differences were addressed and a final value was agreed upon before analysis. The study by Strauss et al37 obtained the highest score of 9 stars out of 10. Study selection received full points as representativeness of the sample (orthopedic residents), sample size, comparability, and use of a validated rating score were utilized. The study used previous standardized exam scores to control for test-taking ability. Additionally, it received full points for outcomes as it utilized a validated measure, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), and blinded scoring of the in-service exam. The lowest score of 1 star was awarded to the study by Deshauer et al.18 This is because the examined cohort was small and does not represent a resident cohort as those examined were extreme athletes and members of the military Special Forces branches. Outcomes were not controlled and were self-reported in nature.

| Study . | Level of evidence . | NOQAS selection . | NOQAS comparability . | NOQAS outcome . | NOQAS total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggarwal et al12 | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Baiu et al13 | III | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Bingmer et al15 | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Deshauer et al18a | III | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Golub et al19a | III | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Jackson et al22a | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Marek et al24 | III | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| McInnes et al26a | III | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| O’Brien et al31a | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Qureshi et al5a | III | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Shanafelt et al33a | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Spiotta et al35 | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Stack et al36a | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Strauss et al37a | III | 5 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| Verheyden et al7a | III | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Weis et al39 | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Wolfe et al40a | III | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Study . | Level of evidence . | NOQAS selection . | NOQAS comparability . | NOQAS outcome . | NOQAS total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggarwal et al12 | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Baiu et al13 | III | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Bingmer et al15 | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Deshauer et al18a | III | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Golub et al19a | III | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Jackson et al22a | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Marek et al24 | III | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| McInnes et al26a | III | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| O’Brien et al31a | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Qureshi et al5a | III | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Shanafelt et al33a | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Spiotta et al35 | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Stack et al36a | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Strauss et al37a | III | 5 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| Verheyden et al7a | III | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Weis et al39 | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Wolfe et al40a | III | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

NOQAS, Newcastle-Ottowa Quality Assessment Scale. aRepresents articles evaluated by the NOQAS adapted for cross-sectional studies

| Study . | Level of evidence . | NOQAS selection . | NOQAS comparability . | NOQAS outcome . | NOQAS total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggarwal et al12 | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Baiu et al13 | III | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Bingmer et al15 | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Deshauer et al18a | III | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Golub et al19a | III | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Jackson et al22a | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Marek et al24 | III | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| McInnes et al26a | III | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| O’Brien et al31a | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Qureshi et al5a | III | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Shanafelt et al33a | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Spiotta et al35 | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Stack et al36a | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Strauss et al37a | III | 5 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| Verheyden et al7a | III | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Weis et al39 | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Wolfe et al40a | III | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Study . | Level of evidence . | NOQAS selection . | NOQAS comparability . | NOQAS outcome . | NOQAS total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggarwal et al12 | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Baiu et al13 | III | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Bingmer et al15 | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Deshauer et al18a | III | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Golub et al19a | III | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Jackson et al22a | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Marek et al24 | III | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| McInnes et al26a | III | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| O’Brien et al31a | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Qureshi et al5a | III | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Shanafelt et al33a | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Spiotta et al35 | III | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Stack et al36a | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Strauss et al37a | III | 5 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| Verheyden et al7a | III | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Weis et al39 | III | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Wolfe et al40a | III | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

NOQAS, Newcastle-Ottowa Quality Assessment Scale. aRepresents articles evaluated by the NOQAS adapted for cross-sectional studies

The McInnes et al26 study focused on Canadian plastic surgery residents. Survey responses were obtained from 80 residents and 10 program directors, and outcomes were focused on personal thoughts about work hour restrictions. The study was awarded 3 stars out of 10, including 2 for selection and 1 for outcomes. Verheyden et al7 examined social issues affecting plastic surgery residents in the United States. Their survey yielded responses from 59 plastic surgery residency programs and included data on plastic surgery residence rates of divorce, pregnancy, substance abuse, and other social issues. The study was awarded 4 stars out of 10, including 3 for selection and 1 for outcomes. Overall the included studies were highly variable in design, cohort size, intervention, and outcome measurements, and the quality of the data was poor with an average score of 4.1. Due to poor study quality and heterogeneity of the cohort and results, a meta-analysis of the data was not performed.

Discussion

Of the 37 articles included in our systematic review, only 2 focused on plastic surgery residents. Our review yielded 17 observational studies related to the topic, and analysis of those studies with the ASPS Evidence Rating Scale and the NOQAS showed subpar data quality. Although there is not a significant amount of literature devoted to wellness and attrition in plastic surgery training, much can be learned from the studies and experiences of attending plastic surgeons and the literature of other surgical specialties. Similar research has prompted the ACGME to further investigate the impact of wellness initiatives in residency and to incorporate physician well-being into their Common Program Requirements.42 However, the effect of such interventions has been minimally researched, and both trainees and training programs could benefit from more focused studies on the specific factors contributing to both wellness and attrition among US plastic surgery residents.

Physicians today face many professional and personal stressors that can negatively impact wellness, including increasing regulations, litigation, clinical demands, less time with patients, large debt loads, and difficultly balancing personal and professional lives.1 Although the goal of our systematic review was to investigate wellness in plastic surgery training, wellness is intrinsically difficult to quantify and individually variable. Most studies related to the topic thus turn their focus to the more quantifiable phenomenon, burnout, which occurs when wellness is lacking. Burnout is a devastating consequence of poor individual wellness, and rates of burnout across the medical field have reached alarming proportions, particularly in the field of surgery.5 Burnout is defined as “a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment.” 43

Burnout can apply to individuals in all walks of life but seems to be more prevalent in human services professions. Christina Maslach, coauthor of the MBI, lists “six areas of work life that encompass the central relations with burnout: workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values.” 44 It is easy to see how each of these areas may relate to burnout within the surgical field. The MBI was utilized in several studies included in our systematic review as a validated measure of physician burnout. One such study, which polled 8000 members of the American College of Surgeons (ACS), found evidence of burnout in 40% of surgeons.45 A similar survey, which accounted for 1691 respondents from the ASPS, found the burnout rate among plastic surgeons to be 29.7%.5 A recently published survey of plastic surgery residents used aspects of the MBI as well as the Stanford Professional Fulfillment Index and demonstrated that 57.5% of surveyed plastic surgery residents were burned out.46 Physician burnout is especially dangerous as it can lead to loss of empathy for patients, decreased ability to teach and learn, poor workplace morale, unprofessional behavior, and self-harm.47

Establishing or maintaining a state of wellness in resident training is crucial to the current and future success and happiness of all residents. Surgical residents are in a unique and challenging phase of their professional development, wherein they are awarded substantial responsibility despite minimal experience. Wellness in residency is both an individual and organizational pursuit. The residents are expected to care for their patients to the best of their abilities and acquire the knowledge and expertise to one day practice autonomously in their field. The residency program faculty are expected to serve as role models as they both educate and support their residents through the process.42

Wellness is not fully encompassed by proper diet, sleep, and exercise. It is also derived from recognition of purpose, passion, and achievement by overcoming challenges and reaching personal goals. Plastic surgery training provides daily opportunities for wellness in this sense, and reminders of the unique opportunity afforded to residents is a valuable tool. Despite such unique and rewarding aspects, rates of burnout among plastic surgery residents remain unnervingly high.6,46

Maslach’s areas of worklife in relation to burnout, in particular workload, control, and reward, may help to explain the discrepancy. The resident workload is notoriously high, even with workhour restrictions. In fact, in the study by Khansa and Janis6 on plastic surgery resident burnout, the number of work hours did not significantly correlate to the rate of burnout. This may be because a resident’s workload demands more than clinical hours worked and includes patient complexity, documentation factors, the presence of support staff, and emotional burdens.48 Residents also may feel a lack of control in aspects such as scheduling, care decisions, and their clinical responsibilities in addition to feelings of inferiority in the medical hierarchy.48 This lack of control is often extended into a resident’s personal life, as their commitment to duty can overshadow personal needs. This could be mitigated if residents were given more protected personal time.49 Although opportunities for intangible rewards abound in resident training, residents may feel a disconnect between the effort they put in and more tangible rewards, especially in terms of care recognition and financial compensation. Residents across all specialties have significant debt from medical school and lower savings than the general public, and surgery residents rank towards the bottom among specialties in terms of financial conservativism.50

Plastic surgery residents must also deal with the social and societal hurdles of adulthood, many of which may be exacerbated by the harsh demands of training and conversely impact the ability of the resident to perform at work. A 2014 survey study sent to all plastic surgery training programs in the United States reviewed issues including divorce, pregnancy, and drug and alcohol abuse.40 The divorce rate among physicians has been estimated at 10% to 20% higher than the general US public, and the survey by Verheyden et al7 showed that 2.9% of plastic surgery residents were divorced during their training period.7,51 Of those divorces, 58.8% affected the residents’ performance, according to their program directors.

In 2003, the ACGME introduced new Institutional Standards for Resident Duty Hours. One article investigating the effects of such regulations showed that resident work hours per week decreased from 100.7 to 82.6, yet change in “resident and faculty emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment did not show statistical significance.” 52 Although reducing hours showed no significant impact on resident burnout, the ACGME has continued to promote resident wellness. The ACGME CLER provides programs with yearly feedback on focus areas, including well-being and professionalism. The CLER report addresses many factors specific to resident burnout, including both oversupervision and undersupervision, fatigue, high patient volume, and nonphysician responsibilities. The CLER also found that systematic strategies to reduce fatigue and burnout were usually instituted by programs in response to an adverse event related to fatigue or burnout. The CLER recommends proactive education and creation of strategies for the prevention of fatigue and burnout.47

One example of a system-wide approach to wellness came out of the Resident Wellness Consensus Summit (RWCS). In 2017, the RWCS met in Las Vegas, NV, and based on discourse within an online Wellness Think Tank, it developed three educator toolkits for residency programs. These toolkits serve as easily accessible, longitudinal lesson plans on wellness topics that were picked by residents for residents. The topics cover second-victim syndrome, mindfulness and meditation, and positive psychology.8 Another group at the summit used a similar method to develop 2 tools: A Resident-Based Needs Assessment Survey on residency wellness programming; and a Worksheet on Implementing New Wellness Initiatives.53 The products of the summit could serve as a skeleton for longitudinal lesson plans on other topics related to wellness, which would give residency programs a simple method of implementing wellness education tailored to the particular needs of their trainees.

The CLER and the products of the RWCS are good starts to addressing wellness in residency, but they do not include any data about the effects of education on wellness. Although these types of interventions may help some individuals to avoid or overcome burnout, it seems more logical that programs should look back at the 6 categories of work stress identified 2 decades ago by Maslach as having a central relation with burnout: workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values. Jennings and Slavin48 provide examples for how residency programs could address each of these factors such as removing unnecessary tasks, and streamlining other processes, “improving residents’ sense of autonomy and self-efficacy at work by teaching communication skills,” education on personal finance and waiving extra fees when possible, enhancing communication between residents and faculty, and many more.48

Personal and organizational wellness remains a critical factor beyond residency and is a worthy lifelong pursuit. Creation of a culture of wellness begins with those at the top of the medical hierarchy. Yet attending plastic surgeons face similar stressors as residents, along with heightened responsibility, malpractice and legal worries, billing requirements, and staying up to date in a rapidly evolving field. Plastic surgeons have a burnout rate of up to 33%.5 A return to wellness will undoubtedly benefit patients, trainees, hospital communities, and medicine as a whole.

The significant risk factors opposing wellness among plastic surgeons include working more than 70 hours per week, microsurgery or aesthetic subspecialties, having more than 2 night calls per week, compensation based on billing vs salary, annual income less than $250,000 or greater than $750,000, and having a spouse who is also employed.5 Significant protective factors include being in practice for over 15 years, serving as a program director, having children, and age over 60 years.5 These factors are largely consistent with similarly collected data on surgeons in general.45

American physicians may benefit from a similar emphasis on personal wellness within their professional guidelines. Surgeon fatigue can be mitigated by employing strategies such as preoperative planning, promoting fatigue awareness, scheduling breaks, and taking unscheduled microbreaks during surgery.9 Hospitals should apply similar programs to educate and support physicians at risk for burnout, and attending physicians should be included in medical school and resident wellness initiatives. At the very least, physicians must be made constantly aware that although the primary goal in medicine is to care for patients, the personal wellness of the physician plays a critical role in the quality of patient care.

Whether interventions take place in the form of education or in a more tangible form, the knowledge base surrounding wellness will benefit from proper implementation and recording of results. Jennings and Slavin suggest an approach similar to quality-improvement initiatives, in which areas for improvement are identified, interventions are implemented, and results are quantified.48 In this way, residency programs across the world can have a better sense of what actually works in regard to program-wide interventions. What is clear from the results of the systematic review is that little research has been dedicated to the wellness and attrition of plastic surgery residency.

Although the aim of this study was to investigate and quantify current research on plastic surgery resident wellness, defining and quantifying wellness is a less than objective task and as a result this study has some important limitations. Most research related to the topic and included in our discussion focuses on a detractor from wellness, burnout, as a more quantifiable measure given standardized tools of assessment. For this reason, our systematic review was limited in scope and did not include studies that did not directly focus on wellness. Additionally, much of the current research is based on cross-sectional surveys, which have demonstrated heterogeneous associations regarding the relative importance of various factors involved in resident wellness. Thus, it is not readily apparent which sorts of interventions will lead to an improvement in the wellness of trainees.

Conclusions

Despite widespread recognition of the importance of physician wellness, little research has been devoted to the implementation of interventions to address factors related to wellness and the prevention of burnout. Burnout is not a new problem for plastic surgery residents, but it is an issue that has more recently been quantified and rigorously studied. There is no identifiable single or quick solution to the problem, but this knowledge base will continue to grow as more programs intervene early in medical education so that matriculants are able to identify the signs of burnout in themselves and peers, develop individualized wellness routines, and reach out to proper support systems. Addressing these issues and building skills early in physician training will decrease the level of physical and psychological attrition in residency, providing future physicians with the abilities to care for their personal wellness as well as the wellness of their patients. Improved physician wellness and decreasing rates of physician burnout, however, are unlikely to manifest until more research into the effects of specific interventions is performed and proper interventions are implemented.

As wellness becomes increasingly emphasized in medical training, it is important to note that the majority of physicians are not burned out. Although plastic surgery requires many personal sacrifices of residents and surgeons, it is a still a highly rewarding specialty wherein most practitioners are able to maintain satisfactory personal wellness. Nonetheless, programs should continue to research and implement wellness interventions. Not only will this create a positive culture and work environment, but it will undoubtedly increase the quality and outcomes of patient care.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES