-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Danielle A Thornburg, Victoria Aime, Sheridan James, Nikita Gupta, Robert Bernard, Martin L Johnson, Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Rare Disease With Dire Consequences in Facial Aesthetic Surgery Patients, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 41, Issue 7, July 2021, Pages NP709–NP716, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjab026

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a rare, inflammatory dermatologic condition characterized by painful cutaneous ulcerations. Herein, we describe the third documented case of PG arising in an elective plastic surgery patient who had undergone an otherwise uncomplicated facelift. We describe the course of her diagnosis and management of PG, which involved her face and neck and then progressed to her lower extremities. Although the etiology remains unknown, PG often arises in a host with another autoimmune disease. In the case described, the patient was diagnosed with an immunoglobulin A gammopathy shortly after she developed PG. Following the case report, the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment strategy of PG is briefly reviewed.

Level of Evidence: 5

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a rare, noninfectious, inflammatory neutrophilic dermatosis that can have devastating consequences.1,2 Symptoms are primarily cutaneous and often begin with sterile pustules that rapidly progress to large, necrotic, and painful ulcerations. Although the majority of affected patients have an underlying autoimmune disease, such as inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis, or hematologic disorders, many patients, especially patients with postoperative PG, have no known predisposing risk factors.3-5 We report a case of PG that occurred following a straightforward, elective facelift, which is believed to be only the third such case reported in the literature.6,7

CASE REPORT

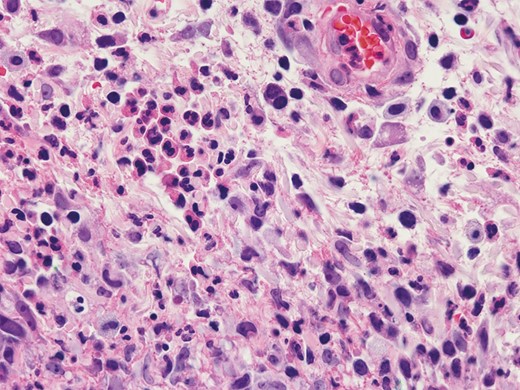

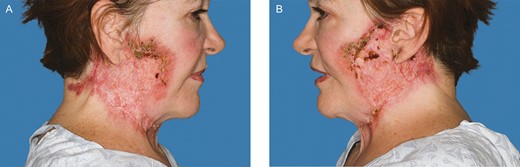

A 67-year-old female with a past medical history of chronic anemia, hyperparathyroidism, sleep apnea, and osteopenia as well as a past surgical history of right hip arthroplasty, rhinoplasty, brow lift, breast augmentation, and malar cheek implants underwent an uncomplicated aesthetic cervicofacial rhytidectomy in the community by a board-certified plastic surgeon in February 2019. The procedure was complicated by a preplatysmal seroma that was drained percutaneously. Eight weeks following the surgery she developed intensely painful, violaceous papules on her malar eminences that spread to her neck. Initial aerobic and anaerobic cultures were negative; however, she was empirically started on antibiotics as well as 3-day course of low-dose oral prednisone without improvement. She was referred to infectious disease and dermatology specialists in her community before being subsequently referred to our academic tertiary hospital (Mayo Clinic Arizona) for evaluation at our dermatology clinic and plastic surgery wound clinic (Figure 1). Clinical suspicion was high for PG and she underwent a punch biopsy of the lesions, which revealed granulomatous dermatitis consistent with PG (Figure 2) and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, which is also rarely found in conjunction with PG. She was treated with high-dose oral steroids for 6 weeks and received local wound care with topical prednisone, tacrolimus 0.1% ointment, and intralesional triamcinolone (1 mL of Kenalog [Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY] 40 mg/mL diluted with 1.25 mL lidocaine and injected intradermally with a 30G needle) (Figures 3 and 4). After she was weaned from systemic steroids the facial lesions worsened and she was subsequently started on infliximab with improvement (Figure 5). Unfortunately, the disease process later progressed to her lower extremities and cyclosporine was added to her regimen (Figure 6). Laboratory tests incidentally revealed an immunoglobulin A monoclonal gammopathy. She was referred to hematology and started on bortezomib. As her lesions resolved, she developed hypervascular, atrophic scars—the typical sequela of PG wounds—and as of October 2020 is undergoing pulsed dye laser treatment (Figure 7). Resolution of her condition is expected to take up to 2 years.

The 67-year-old female patient with neck lesions 4 months following a facelift procedure. Photograph taken at the time of referral. (A) Right. (B) Left. (June 21, 2019.)

Skin biopsy demonstrating mixed dermal inflammation with numerous neutrophils and histiocytes (hematoxylin-eosin, 600× original magnification). (July 5, 2019.)

Further progression of the disease process after the patient was weaned from systemic steroid therapy 6 months after her initial procedure. (A) Right. (B) Left. (August 1, 2019.)

Further progression of the disease process, 3 weeks after follow-up in Figure 3. (A) Right. (B) Left. (August 22, 2019.)

Improvement of facial lesions following 7 infusions of infliximab and local wound care. Photograph taken 1 year after the patient’s initial procedure. (A) Right. (B) Left. (February 21, 2020.)

Disease process involvement of bilateral lower extremities requiring addition of cyclosporine to infliximab therapy 15 months after the patient’s initial procedure. (A) Left. (B) Right. (May 28, 2020.)

After resolution of her facial lesions the patient developed hypervascular, atrophic, and irregular scarring. Photograph taken 16 months after her initial procedure. (A) Right. (B) Left. (July 23, 2020.)

DISCUSSION

Postsurgical PG of the breast has been described with increasing incidence in the aesthetic and plastic surgery literature.8 A recent publication in the Annals of Plastic Surgery9 reviewed 48 articles describing patients who developed PG after breast surgery. Of these, 33 cases involved patients undergoing breast reconstruction after breast cancer. Reporting of PG in aesthetic breast surgery patients is less frequent, with 26 cases reported after aesthetic surgery and only 6 reported after augmentation mammaplasty.9-11

PG occurring after facial surgery has been less frequently described. We believe this patient to be only the third reported case of PG following a facelift procedure. Previous cases following facelift procedures were reported in 2006 in the Aesthetic Surgery Journal7 and in 2019 in the Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery6—the latter a journal less likely to be read by aesthetic plastic surgeons. The paucity of similar reported cases highlights the necessity of increasing awareness of PG after this procedure. As in our case report, the patients initially presented with symptoms between 2 weeks and 2 months after the initial procedure that were thought to be secondary to an underlying bacterial infection and started on antibiotics. After the wounds continued to progress despite antibiotic therapy, all patients were diagnosed with PG and started on immunosuppressant therapy. As seen in the case described by Hobman et al,7 earlier diagnosis seemed to allow for improvement of the disease process with topical therapy rather than systemic immunosuppression as seen in our case and in the case reported by Niamtu.6

The most important role of the plastic surgeon is early identification of PG lesions. These lesions can range from a superficial lesion with varying degrees of granulation tissue with purulent exudate to a large irregular ulceration with a mucopurulent base and a surrounding erythematous and violaceous border.12 The border of the wound is often exquisitely painful, both inherently and with palpation.12,13 Although PG is often an elusive and misdiagnosed disorder, multiple diagnostic scoring systems have been described in the literature and diagnosis is often made both clinically and through histopathologic analysis (Table 1).14-16

| Jockenhöfer et al,14 PARACELCUS scorea . | Maverakis et al,15 Delphi consensus for diagnostic criteria of ulcerative PGe . | Su et al,16 proposed diagnostic criteriaf . |

|---|---|---|

| Major criteria:b P—Progressing disease with clinically evident ulcer developing within <6 weeks A—Assessment of relevant differential diagnosis R—Reddish-violaceous wound border | Major criteria: • Biopsy of ulcer edge demonstrating neutrophilic infiltrate | Major criteria: • Rapidly progressing painful, necrolytic cutaneous ulcer with an irregular, violaceous, and undermined border • Exclusion of other causes of cutaneous ulceration |

| Minor criteria:c A—Amelioration by immunosuppressant drugs C—Characteristically irregular ulcer shape E—Extreme pain >4/10 on visual analogue scale L—Localization of lesion at site of trauma Additional criteria:d S—Suppurative inflammation on histopathology U—Undermined wound border S—Systemic disease associated | Minor criteria: • Exclusion of infection • Pathergy • History of inflammatory bowel disease or inflammatory arthritis • History of papule, pustule, or vesicle ulcerating within 4 days of appearing • Peripheral edema, undermining border, and tenderness at ulceration site • Multiple ulcerations, at least 1 on an anterior lower leg • Cribiform or “wrinkled paper” scar(s) at healed ulcer sites • Decreased ulcer size within 1 month of initiating immunosuppressive medication | Minor criteria: • History suggestive of pathergy or clinical finding of cribriform scarring • Systemic diseases associated with PG • Histopathologic findings of sterile dermal neutrophilia, possible mixed inflammation, possible lymphocytic vasculitis • Rapid response to systemic steroid treatment |

| Jockenhöfer et al,14 PARACELCUS scorea . | Maverakis et al,15 Delphi consensus for diagnostic criteria of ulcerative PGe . | Su et al,16 proposed diagnostic criteriaf . |

|---|---|---|

| Major criteria:b P—Progressing disease with clinically evident ulcer developing within <6 weeks A—Assessment of relevant differential diagnosis R—Reddish-violaceous wound border | Major criteria: • Biopsy of ulcer edge demonstrating neutrophilic infiltrate | Major criteria: • Rapidly progressing painful, necrolytic cutaneous ulcer with an irregular, violaceous, and undermined border • Exclusion of other causes of cutaneous ulceration |

| Minor criteria:c A—Amelioration by immunosuppressant drugs C—Characteristically irregular ulcer shape E—Extreme pain >4/10 on visual analogue scale L—Localization of lesion at site of trauma Additional criteria:d S—Suppurative inflammation on histopathology U—Undermined wound border S—Systemic disease associated | Minor criteria: • Exclusion of infection • Pathergy • History of inflammatory bowel disease or inflammatory arthritis • History of papule, pustule, or vesicle ulcerating within 4 days of appearing • Peripheral edema, undermining border, and tenderness at ulceration site • Multiple ulcerations, at least 1 on an anterior lower leg • Cribiform or “wrinkled paper” scar(s) at healed ulcer sites • Decreased ulcer size within 1 month of initiating immunosuppressive medication | Minor criteria: • History suggestive of pathergy or clinical finding of cribriform scarring • Systemic diseases associated with PG • Histopathologic findings of sterile dermal neutrophilia, possible mixed inflammation, possible lymphocytic vasculitis • Rapid response to systemic steroid treatment |

PG, pyoderma gangrenosum. aThree points each. bTwo points each. cOne point each. dPG likely if ≥10 or more points. eAnalysis revealed 1 major and 4 of 8 minor criteria as the threshold for diagnosis of PG. fDiagnosis requires both major and at least 2 minor criteria.

| Jockenhöfer et al,14 PARACELCUS scorea . | Maverakis et al,15 Delphi consensus for diagnostic criteria of ulcerative PGe . | Su et al,16 proposed diagnostic criteriaf . |

|---|---|---|

| Major criteria:b P—Progressing disease with clinically evident ulcer developing within <6 weeks A—Assessment of relevant differential diagnosis R—Reddish-violaceous wound border | Major criteria: • Biopsy of ulcer edge demonstrating neutrophilic infiltrate | Major criteria: • Rapidly progressing painful, necrolytic cutaneous ulcer with an irregular, violaceous, and undermined border • Exclusion of other causes of cutaneous ulceration |

| Minor criteria:c A—Amelioration by immunosuppressant drugs C—Characteristically irregular ulcer shape E—Extreme pain >4/10 on visual analogue scale L—Localization of lesion at site of trauma Additional criteria:d S—Suppurative inflammation on histopathology U—Undermined wound border S—Systemic disease associated | Minor criteria: • Exclusion of infection • Pathergy • History of inflammatory bowel disease or inflammatory arthritis • History of papule, pustule, or vesicle ulcerating within 4 days of appearing • Peripheral edema, undermining border, and tenderness at ulceration site • Multiple ulcerations, at least 1 on an anterior lower leg • Cribiform or “wrinkled paper” scar(s) at healed ulcer sites • Decreased ulcer size within 1 month of initiating immunosuppressive medication | Minor criteria: • History suggestive of pathergy or clinical finding of cribriform scarring • Systemic diseases associated with PG • Histopathologic findings of sterile dermal neutrophilia, possible mixed inflammation, possible lymphocytic vasculitis • Rapid response to systemic steroid treatment |

| Jockenhöfer et al,14 PARACELCUS scorea . | Maverakis et al,15 Delphi consensus for diagnostic criteria of ulcerative PGe . | Su et al,16 proposed diagnostic criteriaf . |

|---|---|---|

| Major criteria:b P—Progressing disease with clinically evident ulcer developing within <6 weeks A—Assessment of relevant differential diagnosis R—Reddish-violaceous wound border | Major criteria: • Biopsy of ulcer edge demonstrating neutrophilic infiltrate | Major criteria: • Rapidly progressing painful, necrolytic cutaneous ulcer with an irregular, violaceous, and undermined border • Exclusion of other causes of cutaneous ulceration |

| Minor criteria:c A—Amelioration by immunosuppressant drugs C—Characteristically irregular ulcer shape E—Extreme pain >4/10 on visual analogue scale L—Localization of lesion at site of trauma Additional criteria:d S—Suppurative inflammation on histopathology U—Undermined wound border S—Systemic disease associated | Minor criteria: • Exclusion of infection • Pathergy • History of inflammatory bowel disease or inflammatory arthritis • History of papule, pustule, or vesicle ulcerating within 4 days of appearing • Peripheral edema, undermining border, and tenderness at ulceration site • Multiple ulcerations, at least 1 on an anterior lower leg • Cribiform or “wrinkled paper” scar(s) at healed ulcer sites • Decreased ulcer size within 1 month of initiating immunosuppressive medication | Minor criteria: • History suggestive of pathergy or clinical finding of cribriform scarring • Systemic diseases associated with PG • Histopathologic findings of sterile dermal neutrophilia, possible mixed inflammation, possible lymphocytic vasculitis • Rapid response to systemic steroid treatment |

PG, pyoderma gangrenosum. aThree points each. bTwo points each. cOne point each. dPG likely if ≥10 or more points. eAnalysis revealed 1 major and 4 of 8 minor criteria as the threshold for diagnosis of PG. fDiagnosis requires both major and at least 2 minor criteria.

Histopathology of PG may demonstrate suppurative folliculitis with dense neutrophilic infiltration, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and/or granulomatous inflammation, making clinical suspicion vital to a prompt and accurate diagnosis.12,13,17 The definitive etiology of PG is not entirely clear. However, neutrophil dysfunction and an aberrant immune system are thought to be involved in the pathogenesis, along with overexpression of inflammatory mediators, and a hereditary predisposition.17-20

Although PG is defined as a sterile neutrophilic dermatosis in its purest form, a wound culture with bacterial or fungal contamination should not exclude a diagnosis of PG. A bacterial infection can often superimpose the lesions of PG as can colonization with typical skin flora, such as Staphylococcus, further obscuring the diagnosis and treatment. While awaiting wound cultures, it may be beneficial to initiate empiric antibiotic therapy as the anti-inflammatory effects of antibiotics may provide some benefit.21,22 It should be noted, however, that PG often displays pathergy (eg, an exaggerated response to minor trauma), and therefore inaccurate diagnosis can lead to inappropriate debridement of the wounds, precipitating further progression of the condition.3,5,14,16,21

Due to the broad differential diagnosis for PG, a thorough history and workup must be obtained to rule out other etiologies or conditions. Vascular disease or vasculitis, malignancies, exogenous tissue injury, atypical infections, calciphylaxis, necrotizing fasciitis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and other inflammatory disorders have been known to mimic the ulcerative lesions seen in PG.21,23-25 Given that the ulcerations are quite nonspecific, misdiagnosis is common.21,26 When considering PG in the differential diagnosis, one should be sure to ask the patient about disorders known to be concomitant with PG. Systemic inflammatory disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and hematologic dyscrasias, are often seen in association with PG. For example, inflammatory bowel disease has been found in approximately 14% to 30% of PG cases and arthritis in 11% to 25% of PG cases.27,28

It should be noted that postsurgical PG is less likely to be associated with systemic diseases and, similar to our patient, may occur despite multiple prior procedures without development of PG. Postsurgical PG typically occurs approximately 1 week after the inciting procedure. However, much later onset of symptoms has been described.22,29 Early clinical signs of PG in the postoperative period include disproportionate pain at the surgical site, wound dehiscence, surrounding erythema, and possibly hemorrhagic bullae or pustules.8 The affected area may then progress with radial expansion of the erythema and exudative ulceration, leading to wound dehiscence and deeper tissue involvement. Postsurgical PG occurs most frequently at the site of the initial operation; however, it may involve additionally traumatized locations such as intravenous puncture sites. A systematic review of the literature performed in 2014 by Zuo et al found the majority of reported cases of postsurgical PG were after breast surgery (25%), followed by cardiothoracic (14%), abdominal (14%), obstetric and gynecologic (13%), and orthopedic (12%) procedures.8

Historically, there is no gold standard treatment for PG and evidence for treatment is largely based on case series, case reports, and/or local expert opinion.13,23,30 Goals of treatment aim to address the systemic inflammatory component of PG in order to halt ulcer progression, optimize wound healing, and achieve symptomatic pain control.13,24 Treatment modalities may also include various topical agents such as corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, intralesional injections, and systemic use of immunomodulators. Formulating an appropriate treatment regimen for patients with PG should take into account the size, number, and location of PG lesions.

The importance of continued involvement by the operating surgeon in the treatment of the disease process should be emphasized. Noninvasive dressings and avoidance of additional trauma to the wounds is ideal, both to avoid a pathergic response and to mitigate poor aesthetic outcomes. The anatomic location, size, and number of PG lesions should also be considered during decision-making, As seen in our case report, lesions that develop in aesthetically sensitive areas such as the face and neck may result in disfiguring scars. The mainstay of treatment remains systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, with surgical intervention avoided if at all possible due to the potential for pathergy.5,22 Reports of successful treatment of postoperative PG with surgical debridement, skin grafting, hyperbaric oxygen, negative-pressure wound therapy, and combinations of these treatments have been reported in the literature with varying degrees of success; 31,32 however, it is important that the primary surgeon be intimately involved in any decision-making regarding operative interventions.

CONCLUSIONS

Plastic surgeons should be aware of the possibility of postsurgical PG and understand the importance of early identification and the consequences of delay in treatment of this disease. Inappropriate diagnosis and surgical debridement can be detrimental to the patient, leading to aggravation of existing ulcerations and development of new lesions throughout the integument.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mayo Clinic faculty—Dr David DiCaudo for assistance in providing histologic slides for this manuscript and Dr Erwin Kruger for his contribution in the care of this patient.

Disclosures

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article. The photographs included in this manuscript have not been previously published, have not been copyrighted, nor are owned by a company or publisher.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES