-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Maria Chasapi, Andrej Salibi, The Psychological Assessment of Aesthetic Patients: Results of a Survey of the British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons Members, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 41, Issue 6, June 2021, Pages NP706–NP708, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjaa328

Close - Share Icon Share

The increased popularity and demand for cosmetic surgery in the recent years has drawn attention to the importance of patient selection to improve outcomes and reduce the incidence of postoperative dissatisfaction.1 Creating the ideal preoperative screening tool to identify patients who might be at risk of poor postoperative outcomes has attracted an increasing interest recently from plastic surgeons, psychologists, and national bodies.1

Self-reported questionnaires have been utilized prior to cosmetic surgery to screen patients for possible psychological disorders or inappropriate expectations and motivations that might require further formal psychological referral. The evidence of employing validated psychological screening tools among plastic surgeon is not very well represented in the current literature and remains controversial in the clinical setting.2

Therefore, we conducted a 14-question national survey during November 2018 to December 2018, which was sent anonymously to British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons members via the online platform Survey Monkey (San Mateo, CA) (Appendix, available online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com). The aim of this survey was to explore the view of British aesthetic plastic surgeons on the utilization of psychological screening tools, assess current practice, and identify areas for improvement.

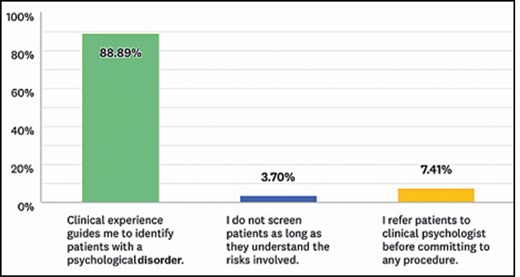

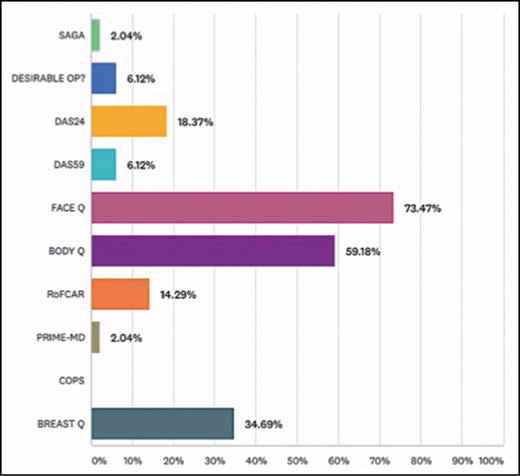

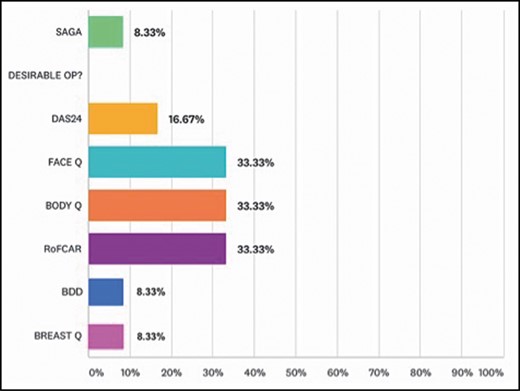

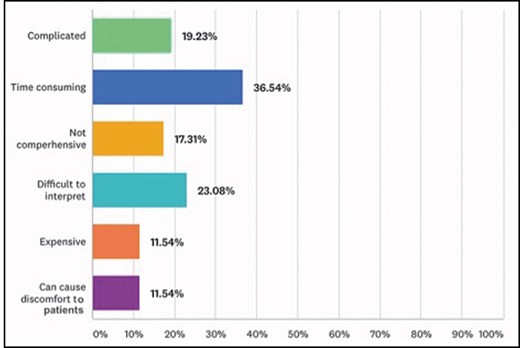

A total of 83 responses were received. The majority (74%) of respondents believed that preoperative psychological screening plays an important role in a favorable postoperative aesthetic outcome. However, only 50% of respondents performed psychological preoperative screening for their patients. When participants were asked to choose a statement that best described their current practice, the vast majority (89%) relied mainly on their clinical experience to identify patients with possible underlying psychological disorder (Figure 1). It was clear that 78% were aware of the various available screening tools. The most known screening tools were the FACE Q (73%) and BODY Q (59%) (Figure 2). Interestingly, only 24% utilized a specific tool regularly, with the FACE Q, BODY Q, and RoFCAR among the most popular (Figure 3), whereas 76% did not employ a screening method because they believed that such tools are time consuming (37%), difficult to interpret (23%), and complicated (19%) (Figure 4).

Current practice among British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons members regarding the preoperative psychological screening.

The proportion of different psychological screening tools known among the participants.

The proportion of different psychological screening tools employed among the participants.

The survey demonstrated that 64% of participants had not received any formal training in the psychological assessment of aesthetic patients throughout their career, and 75% were not aware of any available relevant training (either online or face to face). However, 78% acknowledged that relevant training would be useful. It was indicated that 70% did not have someone working within their practice who had additional training in psychological counseling. Nevertheless, 68% confirmed that they collaborated with a clinical psychologist or a qualified therapist familiar with this patient group who also would take referrals for a preoperative psychological assessment.

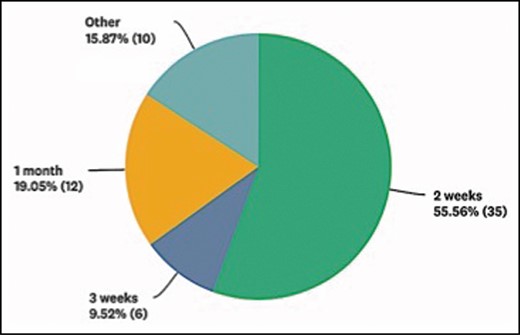

The current practice of over one-half of the participants would involve offering as many consultations as the patient requires prior to proceeding with surgery and an average of at least 2 weeks of a cooling-off period (Figure 5). Although there was a general agreement that preoperative psychological screening was essential to improve postoperative outcomes, there was still a lack of consensus on the effectiveness and practicality of screening tools among British plastic surgeons. This may explain the high percentage of surgeons relying on their intuition and personal experience to identify those patients with underlying psychological disorders and unrealistic expectations.

However, in a similar survey of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery members, 80% of the respondents admit that they have operated on patients only to find out postoperatively the patient had body dysmorphic disorder. This reaffirms that relying solely on personal experience might not be effective after all, and it indirectly confirms the need for a formal reliable assessment tool.3

Our results mirror those in the literature that current tools have not been popular among plastic surgeons and have been criticized for being too complicated, expensive, and tedious.2,4 Therefore, a scientifically sound, clinically significant but simultaneously simple instrument is needed to properly assess patients seeking cosmetic surgery. However, for tools to be clinically effective, appropriate training should be considered to standardize practice.

It is evident that appropriate preoperative screening is pivotal in identifying who might be either unsuitable for surgery or at high risk for adverse postoperative psychosocial outcome and who would therefore benefit from further psychological consultation. The survey has not only highlighted the lack of training in the psychological assessment for this group of patients among aesthetic surgeons but also the importance of it. This notion has drawn significant attention and has been recognized by The British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons with the recent introduction of the “Psychology of the Cosmetic Patient” course. Nevertheless, integrating this into the plastic surgery training curriculum may prove a more productive approach for the long term.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES