-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Chiara Botti, Giovanni Botti, Michele Pascali, Facial Aging Surgery: Healing Time, Duration Over the Years, and the Right Time to Perform a Facelift, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 41, Issue 11, November 2021, Pages NP1408–NP1420, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjab304

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The “time variable” assumes paramount importance, especially regarding facial rejuvenation procedures. Questions regarding the length of recovery time before returning to work, how long the results will last, and the ideal time (age) to undergo this particular type of surgery are the most commonly asked by patients during the initial consultation.

The authors endeavored to determine the healing time, optimal age to perform the surgery, and duration of the results after cosmetic face surgery.

A 35-year observational study of 9313 patients who underwent facial surgeries was analyzed. The principal facial rejuvenation interventions were divided into 2 subgroups: (1) eyelid and periorbital surgery, including eyebrow lift, blepharoplasty, and its variants and midface lift; and (2) face and neck lift. Significant follow-ups were conducted after 5, 10, and 20 years. To evaluate the course of convalescence, the degree of satisfaction with the intervention, and the stability of the results, a questionnaire survey was administered to a sample of 200 patients who underwent face and neck lifts.

The answers given indicated that surgery performed according to rigorous standards allowed for a relatively rapid recovery, and the positive results were stable up to 10 years after surgery. The level of patient satisfaction also remained high even after 20 years.

The “right time” for a facelift, taking into account age, recovery time, and the longevity of the results, is an important consideration for both the patient and the cosmetic surgeon.

Time and its significance as it relates to our lives has always been a fundamental concern. For plastic surgeons and their patients, it is all the more important, especially with regard to surgical procedures for the aging face.1 We endeavored to establish the relationship involving time and facial rejuvenation surgery; in particular, 3 fundamental aspects related to time were analyzed: healing time, optimal age to perform the surgery, and duration of the results.

One of the first questions a patient asks the surgeon during the preoperative consultation precisely concerns the recovery time needed before returning to work and social activities. Another crucial patient concern addressed on the same occasion is the ideal age to undergo this type of surgery. Finally, there is no patient who does not ask, “How long will the effects of the surgery last?” and “How long will I be satisfied with my appearance?”

This article will emphasize how the utilization of different surgical techniques impacts postoperative course while also taking into account individual factors that can lengthen or shorten convalescence. Furthermore, the authors also highlight specific factors that can significantly reduce the postoperative course.

Selecting the most appropriate time to undergo these types of interventions is very subjective and is closely correlated with the wishes of the patient and also influenced by the more purely technical and even “philosophical” approach of the surgeon.2-6 The duration of the results is determined by various factors such as the condition of the tissues, the supporting bone structure, the lifestyle of the patient, and, equally important, the age at which the surgery is performed.7-10

The authors had the opportunity to follow a group of patients for more than 20 years after their initial aesthetic facial surgery. This was possible because these patients came to the same surgeons to undergo additional maintenance surgery or other types of surgery.

METHODS

The study takes into consideration the database of surgeries performed over a 35-year period from January 1983 to January 2018. The principal facial rejuvenation interventions were divided into 2 subgroups: (1) eyelid and periorbital surgery, including eyebrow lift, blepharoplasty, and its variants and midface lift; and (2) face and neck lift. All procedures were performed under written patient informed consent according to the ethical principle and the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The first group consisted of a total of 7550 patients and the second of a total of 1763. The age of the patients in the first group ranged from 29 to 78 years (average age, 54 years), with 78% women and 22% men; the age of the patients in the second group ranged from 36 to 80 years (average age, 57 years), with 83% women and 17% men. The exclusion criteria included patients who had previously underwent similar surgeries and those with unsuitable health conditions for surgery. From the second group (face/neck lift), smokers were also excluded.

The surgical techniques employed with the first group of patients and the number of cases are shown in Table 1. The eyebrows were lifted utilizing 2 types of approaches: the temporal lift and the “direct” lift. Through the temporal incision, dissection is carried out superficially to the deep temporal fascia and extended anteriorly to the temporal crest at the subperiosteal level. The flap was repositioned along a superior lateral vector after extensive release of the fascia and periosteal insertions at the level of the superior and lateral orbital rim. Anchoring was performed with sutures between the superficial fascia and the deep temporal fascia. The “direct” brow lift allowed for the removal of a skin strip above the eyebrows, followed by careful layered suturing of the skin margins. Upper blepharoplasty, in most cases, consisted of the removal of the excess thick skin and the nasal fat pad, whereas in a more limited number of patients, the removal of a strip of orbicularis muscle and a more extensive adipose tissue resection were also performed. As for the lower blepharoplasty, 3 different procedures were employed: the transconjunctival approach with direct removal or repositioning of fat compartments; the transcutaneous approach, again with removal or repositioning of fat compartments and removal of excess skin; and the so-called “extended” blepharoplasty, involving the caudal extension of the dissection in the “prezygomatic” space (behind the orbicularis muscle) for approximately 10 mm below the orbital rim. Finally, the subperiosteal midface lift was performed according to the technique described by the authors in this same journal in 2015.11 In the face-neck lift group, 2 types of surgical techniques were employed: the first, utilized in only 10% of the cases, was based on a more extensive subcutaneous undermining associated with superficial-musculo-aponeurotic-system (SMAS) plication, whereas the second involved limited subcutaneous undermining with a very extensive sub-SMAS dissection and final imbrication.

| Group . | Surgery methods . | Patients, no. . | Surgery technique . | Patients, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (total of 7550) | Brow lifting | 300 | Direct external approach | 65 |

| Trans-temporal approach with endoscope | 5 | |||

| Trans-temporal approach without endoscope | 30 | |||

| Upper blepharoplasty | 2500 | Removal of a strip of orbicularis muscle along with adipose tissue | 30 | |

| Removal of the excess thick skin and the nasal fat pad | 70 | |||

| Lower blepharoplasty | 2100 | Transconjunctival approach | 28 | |

| Transcutaneous approach | 40 | |||

| Extend blepharoplasty | 32 | |||

| Upper/lower blepharoplasty | 1800 | All the above-mentioned blepharoplasty techniques | 100 | |

| Mid-face lifting | 850 | Upper-lateral vector | 60 | |

| Vertical vector | 40 | |||

| Group 2 (total of 1763) | Face neck lifting | 1763 | Extensive subcutaneous undermining | 10 |

| Limited subcutaneous undermining | 90 |

| Group . | Surgery methods . | Patients, no. . | Surgery technique . | Patients, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (total of 7550) | Brow lifting | 300 | Direct external approach | 65 |

| Trans-temporal approach with endoscope | 5 | |||

| Trans-temporal approach without endoscope | 30 | |||

| Upper blepharoplasty | 2500 | Removal of a strip of orbicularis muscle along with adipose tissue | 30 | |

| Removal of the excess thick skin and the nasal fat pad | 70 | |||

| Lower blepharoplasty | 2100 | Transconjunctival approach | 28 | |

| Transcutaneous approach | 40 | |||

| Extend blepharoplasty | 32 | |||

| Upper/lower blepharoplasty | 1800 | All the above-mentioned blepharoplasty techniques | 100 | |

| Mid-face lifting | 850 | Upper-lateral vector | 60 | |

| Vertical vector | 40 | |||

| Group 2 (total of 1763) | Face neck lifting | 1763 | Extensive subcutaneous undermining | 10 |

| Limited subcutaneous undermining | 90 |

| Group . | Surgery methods . | Patients, no. . | Surgery technique . | Patients, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (total of 7550) | Brow lifting | 300 | Direct external approach | 65 |

| Trans-temporal approach with endoscope | 5 | |||

| Trans-temporal approach without endoscope | 30 | |||

| Upper blepharoplasty | 2500 | Removal of a strip of orbicularis muscle along with adipose tissue | 30 | |

| Removal of the excess thick skin and the nasal fat pad | 70 | |||

| Lower blepharoplasty | 2100 | Transconjunctival approach | 28 | |

| Transcutaneous approach | 40 | |||

| Extend blepharoplasty | 32 | |||

| Upper/lower blepharoplasty | 1800 | All the above-mentioned blepharoplasty techniques | 100 | |

| Mid-face lifting | 850 | Upper-lateral vector | 60 | |

| Vertical vector | 40 | |||

| Group 2 (total of 1763) | Face neck lifting | 1763 | Extensive subcutaneous undermining | 10 |

| Limited subcutaneous undermining | 90 |

| Group . | Surgery methods . | Patients, no. . | Surgery technique . | Patients, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (total of 7550) | Brow lifting | 300 | Direct external approach | 65 |

| Trans-temporal approach with endoscope | 5 | |||

| Trans-temporal approach without endoscope | 30 | |||

| Upper blepharoplasty | 2500 | Removal of a strip of orbicularis muscle along with adipose tissue | 30 | |

| Removal of the excess thick skin and the nasal fat pad | 70 | |||

| Lower blepharoplasty | 2100 | Transconjunctival approach | 28 | |

| Transcutaneous approach | 40 | |||

| Extend blepharoplasty | 32 | |||

| Upper/lower blepharoplasty | 1800 | All the above-mentioned blepharoplasty techniques | 100 | |

| Mid-face lifting | 850 | Upper-lateral vector | 60 | |

| Vertical vector | 40 | |||

| Group 2 (total of 1763) | Face neck lifting | 1763 | Extensive subcutaneous undermining | 10 |

| Limited subcutaneous undermining | 90 |

In 15% of the patients, it was necessary to perform a submental approach to the neck by means of a submental incision (4-5 cm), which then allowed a median platysmaplasty to be performed. In addition, suturing of the anterior belly of the digastric muscle was performed in approximately 10% of cases, and partial removal of the submandibular glands was required in only 4% of the cases.

For the purposes of this study, significant follow-ups were conducted after 2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months, and 12 months and, when possible, after 5 years, 10 years, and 20 years. A paper form questionnaire was administered in the office directly to the patients during the follow-up period to evaluate the postoperative convalescence, the entourage reaction to the surgery and the state of patient satisfaction after surgery (Appendix, available online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com).

RESULTS

Time: Healing

The duration of the convalescence depends both on individual variables related to the patient and on the surgical technique. Variables relating to the patient include the intrinsic quality of the tissues (thickness and elasticity of the skin, thickness of the subcutaneous panniculus, conformation of the facial skeleton, etc), the patient’s age and various aging factors (thinning of the soft tissues, bone atrophy, actinic damage etc). The patient’s strict adherence to postoperative instructions is also fundamental. Regarding the surgical technique employed, undoubtedly less aggressive techniques normally result in faster postoperative recovery. However, it is often necessary to utilize more invasive techniques to obtain a more valid and stable result over time.

More specifically, the authors noted that careful surgical dissection, respecting anatomical planes, performed as much as possible with electrocautery and combined with precise tissue reconstruction (while taking into account the need for dead space closure) are the foundations for rapid healing. The type of postoperative dressing, in some cases, also plays an important role in limiting edema and ecchymosis, which will be minimized if moderate compression is applied to the areas subjected to undermining, especially in the region of the lower eyelid, by applying a 3M Reston foam (4 mm) compression dressing (3M, St. Paul, MN) kept in place for 4 days. Whereas with facelift surgery, the authors believe that postoperative compressive dressing is less important and, moreover, poorly tolerated by the patients and therefore should only be maintained for a maximum of 24 hours. Furthermore, it is important to limit subcutaneous dissection in favor of deep extended dissection and to seal the dead space utilizing fibrin glue and transcutaneous sutures (Figure 1).12,13 Regarding postsurgical medical therapy, it should be noted that the authors’ experience indicates that, although the prophylactic administration of antibiotics and steroids can be beneficial, the utilization of anti-inflammatory drugs after surgery does not significantly modify the postoperative course.

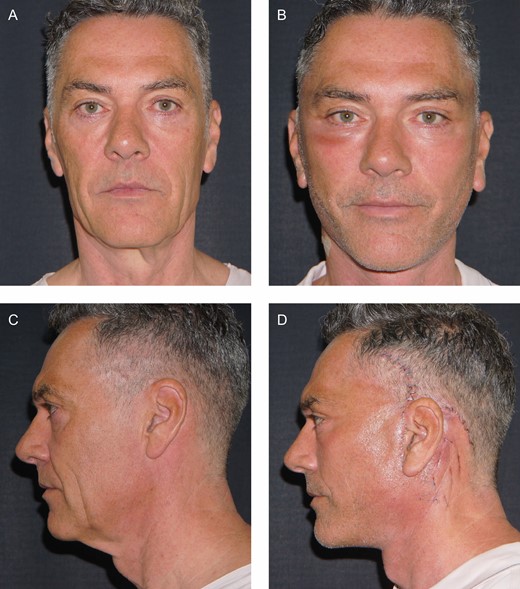

If the intervention is performed according to the standards described in the text, convalescence is usually rather rapid. (A, C) Preoperative and (B, D) 2 days postoperative photos of this 52-year-old male patient at the clinic for removal of the transcutaneous suture network in the infra/retroauricular region. Note the absence of ecchymosis and the presence of only a moderate edema thanks to the limited subcutaneous dissection and the sealing of dead space with fibrin glue and A-net.

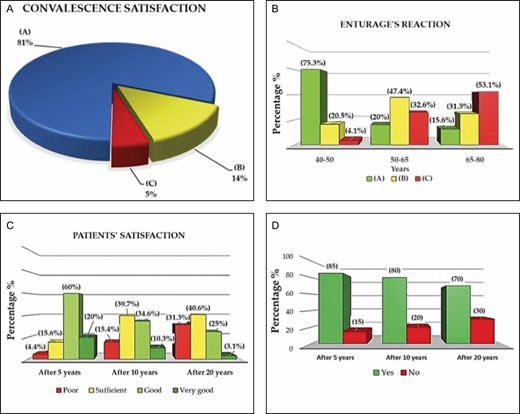

As for the patients who underwent face-neck lifts, to evaluate the degree of satisfaction after the surgery, a questionnaire survey was administered to a sample of 200 patients in which, among other things, they were asked whether the convalescence had progressed according to their expectations and the surgeon’s forecast. The answers given indicated that, in most cases, surgery performed according to rigorous standards allowed for a relatively rapid recovery within the expected time (Figure 2).

The chart shows the results for the first question of the survey regarding postsurgery (face-neck lifting) convalescence satisfaction of 200 patients. (A) A total 81% (162 *pt.) patients confirm that the recovery is in line with the presurgery information given by the surgeon. (B) A total 14% (28 *pt.) patients indicate a longer-than-expected postsurgery convalescence and only (C) 5% (10 *pt.) of patients are dissatisfied with the long recovery time (*pt. = patients). (B) The bar plot shows the results for the third question of the survey regarding (face-neck lift) postsurgery satisfaction of 200 patients divided into 3 groups in this case study: 5, 10, and 20 years after surgery. The satisfaction level is evaluated considering 4 options proposed in the patient survey: poor, sufficient, good, and very good. The trend shows that the very good and good options decrease at long-term follow-ups. A total 60% and 20% of the patients confirm that after 5 years, the result is good and very good, respectively. After 10 years, the very good result decreases to 10.3%, and the good option is still confirmed by most of the patients (34.6%). Only 4.4% report poor results after 5 years, highlighting the high efficiency of the surgical method. The follow-up after 20 years can be considered very challenging; nevertheless, 32 patients were able to complete the survey. A good result is still present at 25%, but the majority of the patients judge the result as sufficient (40.6%). In conclusion, the positive results are stable up to 10 years after the operation. (C) The bar plot shows the results for the third question of the survey for the (face-neck lift) postsurgery satisfaction for 200 patients divided into 3 groups in this case study: 5, 10, and 20 years after surgery. The satisfaction level is evaluated considering 4 options proposed in the patient survey: poor, sufficient, good, and very good. The trend shows that the very good and good responses decrease as the time elapsed following the face-neck lift operations. A total 60% and 20% of the patients confirm that after 5 years, the results are good and very good, respectively. After 10 years, the very good response decreases to 10.3%, and the good response is still indicated by most of the patients (34.6%). Only 4.4% indicate a poor result after 5 years, highlighting the high efficiency of the surgery method. The follow-up after 20 years can be considered very challenging; nevertheless, 32 patients were able to complete the survey. A good result is still present at 25%, but the majority of the patients judge the result as sufficient (40.6%). In conclusion, the positive results are stable up to 10 years after the operation. (D) The bar plot shows the results for the fourth question of the survey for the (face-neck lifting) postsurgery satisfaction level for 200 patients: Do you believe that you would have looked older if you had not had the surgery? Three patient groups are considered in this question: 5, 10, or 20 years after surgery (for the follow-up after 20 years, only 32 patients were able to complete the survey). The result shows a positive confirmation for all 3 groups (84%, 79%, 68%), highlighting the efficacy of the surgery.

Time: When to Perform Surgery

For each patient, the right time to undergo surgery will vary because the ideal time to undergo plastic surgery is when a person experiences a disharmony between their external appearance and self-perception. Therefore, the ideal time for a patient to undergo, for example, a facelift is when looking in the mirror, they no longer identify with the image reflected. However, surgeons must sometimes ask themselves whether it is ethical, for example, to perform a facelift on a 25-year-old patient who believes they need it. A surgeon must be aware of these ethical limits and must sometimes refuse to perform surgery in order not to cross those limits.

Of course, performing a facelift on a relatively young patient (say 40/50 years) has 2 important advantages. First, their friends, relatives, and colleagues will not be aware that the patient underwent the procedure because the change in their appearance will be less dramatic, and the patient may be able to say that they had been on a relaxing vacation or at a spa. In the evaluation questionnaire administered to the patients in the second group, the second question precisely concerned this issue, that is, how aware were the patient’s relatives, friends, and colleagues that the patient had undergone surgery. The results are reported in Figure 2. The other advantage concerns how long the results will last, which will be longer if the surgery is performed at a younger age, as will be discussed in greater detail later.

Time: Longevity of the Results Over the Years

Of all the questions that patients ask their surgeon during the preoperative consultation, the most common is how long the results will last. Some patients mistakenly believe that the results will last forever. Obviously, the surgeon’s duty is to emphasize that aging will continue inexorably and, consequently, the positive results obtained immediately following the surgery will gradually diminish. A contrary belief is that a facelift will result in an immediate positive effect but will ultimately accelerate the aging process. In other words, it is a sort of “pact with the devil” for which one trades short-lived youth for more rapid aging later. This is obviously an “urban legend” without any truth. In their many years of experience, the authors have been able to verify that relative youthfulness achieved by a facelift is maintained over time despite the natural aging process. The patients shown in Figures 3, 4, and 5 illustrate how the results obtained can be maintained even 15 to 20 years after surgery. Indeed, if a patient undergoes a facelift at the age of 50 after which they appear 10 years younger, they will likely continue to appear 10 years younger at the age of 60 and so on. The third and fourth questions in the questionnaire concerned the degree of patient satisfaction and whether they felt that if they had not undergone the face lift, they would have looked older at 5, 10, and 20 years after the procedure (Figure 2). It should be noted, however, that of the 200 patients who responded to the questionnaire, only 32 of the patients who had undergone a facelift 20 years before were able to complete the questionnaire. It is essential to bear in mind that the duration of the results is affected by various factors, including the condition of the tissues, the extent of the correction, the surgical technique employed, as well as the age at which the operation is performed.

This 45-year-old female patient underwent an extended deep-plane facelift. (A, D, G) Before, (B, E, H) 5 years, and (C, F, I) 15 years after surgery at age 60 years. Note how, utilizing the appropriate technique, the results remained quite stable both in the cheek and neck regions.

(A, D, G) Before, (B, E, H) 5 years, and (C, F, I) 20 years after sub-periosteal midface lift surgery associated with deep-plane facelift performed in this 48-year-old female patient. It should be noted that long-term stable results are directly related to the young age at which the surgery was performed.

(A, D, G) Before, (B, E, H) 5 years, and (C, F, I) 20 years after sub-periosteal midface lift surgery associated with deep-plane facelift performed in this 53-year-old female patient. Even after 20 years and although the patient lost 8 kg, soft tissue repositioning was maintained well both in the middle facial region (note the level of the nasal-jugal groove) and in the correction of jowls and cervical laxity.

Complications

Regarding complications, the authors point out that the first group included both relatively simple procedures (direct brow lift, simple blepharoplasty, etc) with a lower incidence of postoperative problems as well as more complicated procedures (extensive blepharoplasty and subperiosteal midface lift) with a different postoperative impact. The authors considered it appropriate to summarize the data, grouping all the complications reported regardless of the type of procedure performed, because a detailed analysis of complications is beyond the scope of this work. It should be noted that when a patient presents with even the slightest eyelid hypotonia, the authors always responded immediately with a preventive reinforcement of the eyelid suspension system with appropriate canthoplasty.14 The complications in the 2 groups of patients were reported in Table 2.

| Group . | Complications . | Patients, no. . | Patients, % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Transient chemoses | 528 | 7 |

| Lower lid displacement | 226 | 3 | |

| Hematomas | 38 | 0.5 | |

| Infections | 26 | 0.35 | |

| Poor quality scars | 60 | 0.8 | |

| Temporary difficulties in opening/closing eyes | 151 | 2 | |

| Local hyposensitivity | 75 | 1 | |

| Early recurrence of the defect | 226 | 3 | |

| Group 2 | Hematoma | 53 | 3 |

| Prolonged edema | 49 | 2.8 | |

| Transient paresis | 32 | 1.8 | |

| Poor quality scars | 26 | 1.5 | |

| Asymmetry | 21 | 1.2 | |

| Skin necrosis | 9 | 0.5 | |

| Infections | – | – |

| Group . | Complications . | Patients, no. . | Patients, % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Transient chemoses | 528 | 7 |

| Lower lid displacement | 226 | 3 | |

| Hematomas | 38 | 0.5 | |

| Infections | 26 | 0.35 | |

| Poor quality scars | 60 | 0.8 | |

| Temporary difficulties in opening/closing eyes | 151 | 2 | |

| Local hyposensitivity | 75 | 1 | |

| Early recurrence of the defect | 226 | 3 | |

| Group 2 | Hematoma | 53 | 3 |

| Prolonged edema | 49 | 2.8 | |

| Transient paresis | 32 | 1.8 | |

| Poor quality scars | 26 | 1.5 | |

| Asymmetry | 21 | 1.2 | |

| Skin necrosis | 9 | 0.5 | |

| Infections | – | – |

| Group . | Complications . | Patients, no. . | Patients, % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Transient chemoses | 528 | 7 |

| Lower lid displacement | 226 | 3 | |

| Hematomas | 38 | 0.5 | |

| Infections | 26 | 0.35 | |

| Poor quality scars | 60 | 0.8 | |

| Temporary difficulties in opening/closing eyes | 151 | 2 | |

| Local hyposensitivity | 75 | 1 | |

| Early recurrence of the defect | 226 | 3 | |

| Group 2 | Hematoma | 53 | 3 |

| Prolonged edema | 49 | 2.8 | |

| Transient paresis | 32 | 1.8 | |

| Poor quality scars | 26 | 1.5 | |

| Asymmetry | 21 | 1.2 | |

| Skin necrosis | 9 | 0.5 | |

| Infections | – | – |

| Group . | Complications . | Patients, no. . | Patients, % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Transient chemoses | 528 | 7 |

| Lower lid displacement | 226 | 3 | |

| Hematomas | 38 | 0.5 | |

| Infections | 26 | 0.35 | |

| Poor quality scars | 60 | 0.8 | |

| Temporary difficulties in opening/closing eyes | 151 | 2 | |

| Local hyposensitivity | 75 | 1 | |

| Early recurrence of the defect | 226 | 3 | |

| Group 2 | Hematoma | 53 | 3 |

| Prolonged edema | 49 | 2.8 | |

| Transient paresis | 32 | 1.8 | |

| Poor quality scars | 26 | 1.5 | |

| Asymmetry | 21 | 1.2 | |

| Skin necrosis | 9 | 0.5 | |

| Infections | – | – |

Discussion

Of course, patients who undergo facial rejuvenation surgery would like the results to be immediate, very natural looking, and undetectable by others and to last forever.1-6 Therefore, the “time variable” is a real obsession for the plastic surgery patient.15

With the aim of offering quick results, a variety of techniques, some more valid than others, have been proposed, such as traction threads, very limited incisions and detachments, and different “magic” devices, etc—all which theoretically reduce convalescence time.16-28 However, the quality of the results is still determined by the appropriateness of the intervention and consequently, these “minimally invasive” approaches in most cases offer disappointing results.2-5

In the case of eyelid surgery, for example, in recent years there have been many bizarre proposals to correct excess skin on the upper eyelids employing lasers, without incisions, with the aim of inducing scar retraction to eliminate dermatochalasis.29-31 In fact, this approach yields discrete results in only a few selected cases where there is a minimal amount of excess skin to begin with. In the majority of cases, the result is absolutely substandard.1

Similarly, in the search of a scalpel-free facelift, the utilization of traction threads and devices (radiofrequency, ultrasound, shock waves, etc)16-19,25-27 theoretically capable of causing a shrinkage of soft tissues has been proposed. Unfortunately, traction threads rarely offer tangible results because the principle on which their utilization is based is erroneous.1 The threads are inevitably inserted into adipose tissue, which is notoriously lacking a strong fibrous support structure and involve no dissection, which is fundamental for mobilizing and repositioning ptotic (descended) tissue. Furthermore, their utilization does not allow for the removal of excess soft tissues, which consequently remain unchanged. Moreover, with both threads and devices, the results are not only disappointing, but their utilization often makes the execution of any subsequent effective surgical interventions more difficult because of the diffuse and disordered tissue fibrosis. The same issue applies to the so-called “mini lifts,” “weekend lifts,” etc.32-34 The inadequate dissection and difficulties with tissue distribution, as well as the impossibility of creating a valid support, usually yield poor results.21,35-37

The aim of these “minimally invasive” methods is extremely rapid recovery time.32 However, the reason someone elects to have plastic surgery is to effectively correct defects related to aging. It matters little that the convalescence time has been shortened if the surgical results do not satisfy the patient’s primary concern. It is possible to reduce the postoperative recovery period with proven effective interventions. For example, a thorough knowledge of loco-regional anatomy is required to perform dissections in the appropriate plane, utilizing electrocautery at moderate settings, which results in decreased blood suffusion. The authors believe the choice of detachment planes is equally important, preferring where possible a deep dissection below the SMAS to reposition skin, fat, facia, and muscles in a composite flap.1,6

In palpebral and periorbital surgery, the authors’ reference is the transconjunctival approach. However, when necessary, we do not hesitate to employ the transcutaneous approach, preferably with retro-orbicularis dissection and possibly subperiosteal dissection, which achieves an optimal result while shortening convalescence.11,37-41 However, in many cases it is also necessary to perform a subcutaneous dissection to facilitate the removal of excess skin.6 In the facelift procedure, the subcutaneous plane, where hematomas most frequently occur, is considerably reduced by repositioning the composite flap after an extended deep dissection, ideally leaving only a 3- to 4-cm area in front of the ear where the SMAS is separated from the skin.

Of course, it must be emphasized that the dissection in the infra/retroauricular area can only be performed in the subcutaneous plane where blood pooling can form, which requires evacuation and prolongs and complicates the postoperative course.42 For this reason, the authors consider it appropriate to apply fibrin glue to all sites of superficial undermining associated with the utilization of a transcutaneous mesh suture in the retro/infra-auricular area to completely seal the residual dead space.12-13 Particularly in the eyelid region, it is advantageous to apply a moderately compressive dressing consisting of 4-mm-thick properly shaped sponges, which should be kept in place for 4 days to shorten convalescence.6,11

The ideal time to perform facial rejuvenation procedures deserves careful discussion. The current trend in the “more advanced” areas of the world is to perform these procedures on younger and younger patients.43-45 More frequently, younger patients are requesting surgical interventions convinced that they really need them. We can identify at least 2 reasons for this trend: appearance has come to assume greater importance in many people lives46 and there has also been an increase in the commercialization of cosmetic surgery boosted by some manufacturers of various surgical devises.

Of course, it is not possible to precisely define an ideal age to perform any kind of plastic surgery. A facelift, for example, which is not free from complications, should only be performed when there is a real indication. Undergoing a facelift around the age of 45/50 years ensures that the changes are not too obvious and promises longer-lasting results due to the slower rate of the physiological aging processes.

Another question frequently asked during the first consultation concerns the duration of results. Before answering this question, the surgeon should carefully evaluate the various techniques to ensure the longest-lasting result with the minimal complications. Previously, the authors had sought to identify the most effective surgical procedures for each area of the face and neck.1,6 In particular, they noted that repositioning the soft tissues along a vertical vector in the middle third of the face ensured a more natural and longer-lasting result, so we concluded that the subperiosteal midface lift is the most appropriate approach to correct soft tissue ptosis.11

To obtain a long-lasting result in the lower third of the face and neck, it is necessary to reposition the SMAS by imbrication and plication.1,6,47-54 In reviewing the relevant literature, we found no prospective randomized studies that demonstrate the superiority of one technique over the other.55 Some articles argue that techniques involving SMAS flap elevation are preferable for more effective and durable results, whereas others argue that plication alone ensures the same results.56-62

In fact, there is no single optimal approach to a facelift, and most surgeons prefer one technique over another based on their own specific training and experience. To determine the most effective technique, approximately 15 years ago the authors performed facelift surgery on 30 consecutive patients employing the SMAS technique on the right side and lifting and imbricating on the left side. The plications were performed by suturing the SMAS onto itself on the right side, whereas on the left side the SMAS flap was anchored to firm structures (deep temporal fascia, periosteum of the posterior third of the zygomatic arch, Lorè’s fascia, mastoid periosteum). One year later, the right side where the plications had been performed already showed signs of drooping, which were absent on the left side (Figure 6). The authors concluded that to obtain a longer-lasting result, it is preferable to lift the SMAS and anchor it to firm structures.

Imbrications and plications comparison: (A, C) preoperative and (B, D) 1-year postoperative photos of these female patients at the age of 44 and 47 years, respectively, demonstrate how the left side treated with imbrication appears in better condition both at the mandibular and neck lines. These cases belong to the series of 30 patients in which the superficial-musculo-aponeurotic-system was repositioned on the left side with imbrications and on the right one only with plication.

The evaluation of these research results cannot be considered completely free of bias due to the interference of other interventions performed simultaneously (lipofilling, resurfacing, lip lift, etc) and the experience gradually gained by surgeons over the years, which resulted in progressively better performance. Moreover, patients who have been lost during the follow-up could not be evaluated in a long-term follow-up.

This research is not provided with the potency of the experimental study; however, it includes a very extensive experience spanning 35 years and its success depends on the incredibly high number of patients studied and on the ability of the same surgeons to perform and analyze this huge amount of data.

Conclusions

The time factor—the healing time, the optimal “time” (age) at which to undergo the intervention, and time regarding the duration of the results—represents without doubt the fundamental aspect of facial cosmetic surgery. The surgeon performing this kind of surgery must therefore be able to choose the most suitable techniques to dominate the time factor.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Drs C. Botti and G. Botti are plastic surgeons in private practice in Salò, Italy

Dr Pascali is a plastic surgeon in private practice in Rome, Italy