-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Pierre Tawa, Nicolas Brault, Vlad Luca-Pozner, Laurent Ganry, Ghassen Chebbi, Michael Atlan, Quentin Qassemyar, Three-Dimensional Custom-Made Surgical Guides in Facial Feminization Surgery: Prospective Study on Safety and Accuracy, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 41, Issue 11, November 2021, Pages NP1368–NP1378, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjab032

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Facial feminization surgery (FFS) includes several osseous modifications of the forehead, mandible, and chin, procedures that require precision to provide the patient with a satisfactory result. Mispositioned osteotomies can lead to serious complications and poor aesthetic outcomes. Surgical cutting guides are commonly employed in plastic and maxillofacial surgery to improve safety and accuracy. Yet, to our knowledge, there is no report in the literature on the clinical application of cutting guides in FFS.

The authors sought to assess the safety and accuracy of custom surgical cutting guides in FFS procedures.

A prospective follow-up of 45 patients regarding FFS with preoperative virtual planning and 3-dimensional custom-made surgical guides for anterior frontal sinus wall setback, mandibular angle reduction, and/or osseous genioplasty was conducted. Accuracy (superimposing preoperative data on postoperative data by global registration with a 1-mm margin of error), safety (intradural intrusion for the forehead procedures and injury of the infra alveolar nerve for chin and mandibular angles), and patient satisfaction were assessed.

A total 133 procedures were documented. There was no cerebrospinal fluid leak on the forehead procedures or any infra alveolar nerve or tooth root injury on both chin and mandibular angle operations (safety, 100%). Accuracy was 90.80% on the forehead (n = 25), 85.72% on the mandibular angles (n = 44), and 96.20% on the chin (n = 26). Overall satisfaction was 94.40%.

Custom-made surgical cutting guides could be a safe and accurate tool for forehead, mandibular angles, and chin procedures for FFS.

Gender dysphoria is defined by the American Psychiatric Association as “a conflict between a person’s physical or assigned gender and the gender with which he/she/they identify. People with gender dysphoria may feel very uncomfortable with the gender they were assigned, sometimes described as being uncomfortable with their body or being uncomfortable with the expected roles of their assigned gender.” 1

Treatment of gender identity disorder requires a multidisciplinary approach to help patients fully live their identity. Described for the first time by Douglas Ousterhout in 1987,2 facial feminization surgery (FFS) is one of the major surgical steps in the global management of gender dysphoria. This includes several well-established surgical techniques to provide a more feminine aspect to the face, primarily for transgender patients wishing to make a male-to-female transition.

The main facial characteristics differentiating men from women involve the facial skeleton; therefore multiple surgical techniques have been described to feminize it, such as frontal sinus setback and recontouring, mandibular angles reduction, or genioplasty.2-5 However, these procedures require a high level of precision, and they are variable and specific to each patient. Furthermore, osteotomies can be difficult to estimate for novice surgeons and are not deprived of complications. During a frontal sinus setback, an osteotomy positioned too high or too laterally exposes the patient to the risk of intracranial intrusion, with potential cerebrospinal fluid leaks and infections.6 Procedures on the mandibular angles and chin are exposed to the risk of inferior alveolar nerve injury.7-9 In addition, mispositioned osteotomies can lead to inappropriate aesthetic outcomes.

Surgical cutting guides are commonly utilized in head and neck surgery, including FFS, for both accuracy and improved outcome predictability.10,11 Recently, Gray et al studied the virtual surgical planning (VSP) with intraoperative cutting guides for frontal sinus impaction, mandibular angle reduction, and genioplasty on cadavers.12 They concluded an improvement of efficiency, safety, and accuracy on the 3 procedures by utilizing cutting guides. Despite these encouraging results on cadavers, to our knowledge, there is still no clinical evidence of the reliability and the accuracy of cutting guides in FFS.

Herein, we present a prospective study on 45 patients who underwent FFS utilizing custom-made surgical guides. The aim of this report was to assess the clinical safety and radiological accuracy of the respective cutting guides.

METHODS

From May 2018 to September 2019, 45 patients who underwent FFS were included in our prospective protocol of preoperative virtual planning and 3-dimensional (3D)-printed custom-made surgical guides. Each patient underwent a preoperative computed tomography (CT) with 3D reconstruction to evaluate the anatomical morphology of the forehead, mandibular angles, and chin.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: type III frontal prominence according to the Ousterhout classification (ie, a large frontal hump with prominent frontal sinus requiring frontal impaction treatment), acute mandibular angles with indication for bilateral resection, and wide and thick chin with indication for vertical resection. Exclusion criteria were a type I or type II frontal prominence according to the Ousterhout classification, patients who already underwent a FFS, or patients not requiring mandibular angles resection or genioplasty.

This study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki on human studies. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Preoperative 3D Virtual Planning

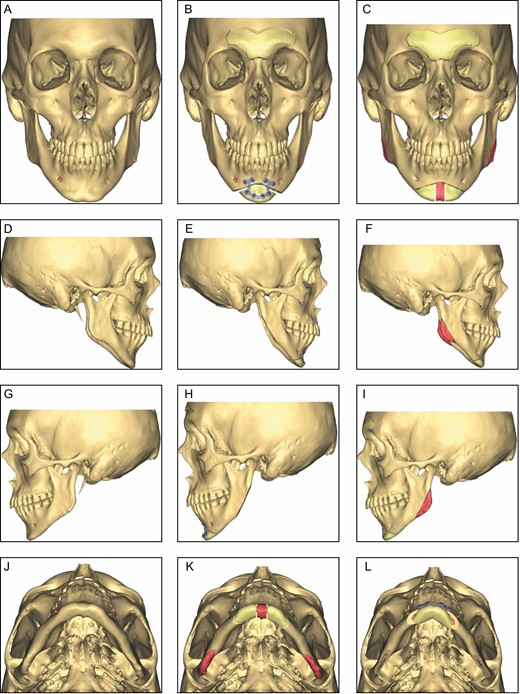

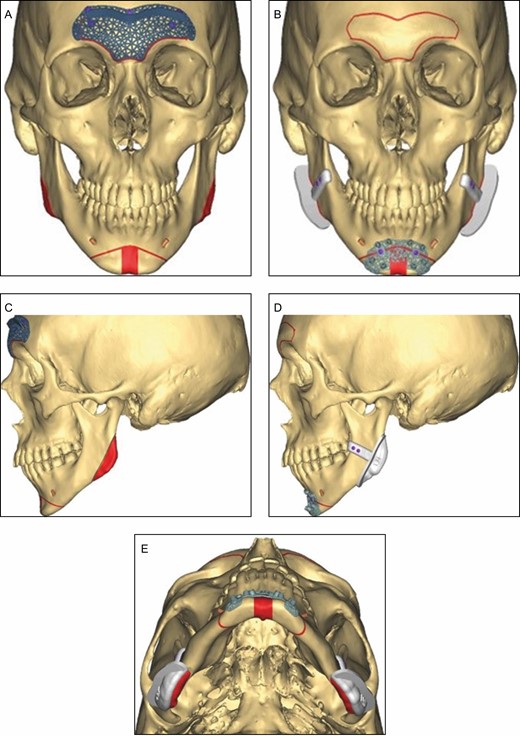

For each patient, based on the preoperative CT DICOM data, a 3D model of the skull was prepared to discuss the modifications on each area. The virtual 3D models were imported into ProPlan CMF 3.0 (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) for surgical planning. A simulation of the postoperative result was created together with the patient during the preoperative consultation (Figure 1). The cutting guides were designed in collaboration with the Materialise engineering team utilizing 3-matic software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) according to the planning (Figure 2). Materials employed for the guides were titanium for the forehead and chin, and polyamide for the mandibular angles.

Three-dimensional virtual surgical planning. Preoperative anatomy (A, D, G, J). Osteotomy lines and osseous resection bands (in red) are determined based on the preoperative planning (C, F, I, K). Virtual planning of the desired postoperative result in collaboration with the patient (B, E, H, L).

Custom surgical cutting guides for anterior frontal sinus setback (A, B), mandibular angle reduction, and genioplasty (C-E).

On the forehead, osteotomies and setback of the frontal bone were simulated to reduce the sinus prominence. The osteotomy lines were placed around the sinus with a 45-degree plane in the upper region and a plane that started from 4 mm above the supraorbital foramen.

On the chin, 3 planes were carried out to define the osteotomy lines. The horizontal plane was placed below the roots of the teeth at least 4 mm away from the mental foramen. Two other vertical planes were placed medially and spaced by the width of desired removal of bone. Mandibular osteotomy lines were placed at least 4 mm below the inferior alveolar nerve to avoid injuries.

Case-specific posters that could be displayed in the operating room were delivered with the guides together with the regulatory documentation. These posters indicate relevant information for the case, including screw size and the simulated osteotomy lines.

Surgical Technique

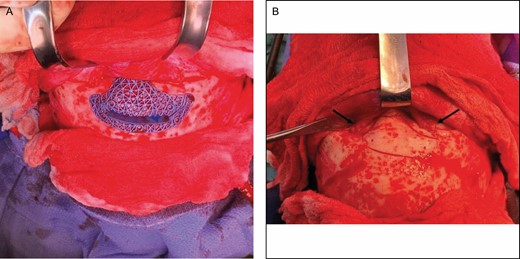

All the cases were performed by the same senior surgeon (Q.Q.). Surgical approach on the forehead was bicoronal as described by Capitán et al.13 The custom guide was applied on the forehead and stabilized by custom-made screws. The osteotomy was performed with a sagittal saw as indicated by the guide. Once the osteotomy was completed, the cutting guide was removed and the bony fragment was detached (Figure 3). When necessary, a frontal sinus septum resection was performed to obtain the desired impaction. The edges were contoured with a round burr, following surgeon appreciation to avoid irregularities. Finally, the bony fragment was reattached to the skull with 2 micro plates (0.6 mm thick). Micro screws (1.5-mm diameter) were utilized to fixate custom guides and plates (Figure 4). During the same procedure, the fronto-naso-orbital area could be trimmed with a round burr to obtain a harmonious forehead shape.

Custom cutting guide for anterior frontal sinus setback on this 43-year-old transgender patient who underwent male-to-female transition. (A) Osteotomy is performed with a sagittal saw following the guide osteotomy lines. (B) Supraorbital pedicles (black arrows) are respected.

Perioperative result of forehead impaction and supraorbital rims contouring on this 43-year-old transgender patient who underwent male-to-female transition. The bone fragment is attached with titanium plates. (A) Front view. (B) Side view.

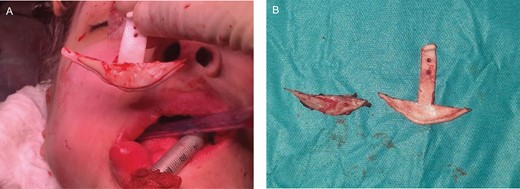

Mandibular angles and chin were approached intraorally with vestibular incision. The gonial angle surgical guide was positioned on the outer surface of the gonial angle and immobilized with 2 custom-made screws in the ramus (Figure 2). Osteotomies were performed with a sagittal saw following the upper edge of the guide (Figure 5). The chin surgical guide was also attached with custom-made screws. The 2 bone fragments resulting from genioplasty were reattached with 1 single custom-made titanium plate.

(A, B) Mandibular angles reduction on this 43-year-old transgender patient who underwent male-to-female transition.

Safety and Accuracy

Postoperative follow-up was planned for each patient at 1 week, 3 weeks, and 3 and 6 months. All patients were asked to undergo a postoperative CT scan at the 6-month consultation.

Safety was assessed by intradural intrusion for the forehead procedures and injury of the inferior alveolar nerve for genioplasties and mandibular angles reductions. Postoperative complications were also documented, such as infection, hematoma, seroma, palpable irregularities, and need for revision. Mucocele, bone resorption, scar nonunion, osteitis, and material displacement were searched on the postoperative CT scan.

Accuracy was assessed by superimposing preoperative data on postoperative data by global registration with a margin of error of 1 mm for each area (Supplemental Figure 1). The distance separating each point of the postoperative model from the planned model was measured for each area and the percentage of points less than 1 mm from the planned model were calculated.14 The visual evaluation of accuracy was presented as a color scale directly on 3D views.

Satisfaction Survey

At the 6-month consultation, each patient were asked to fill an anonymous written satisfaction questionnaire by the surgical resident.

RESULTS

All the data were collected prospectively. The average age was 31.3 years (range, 19-49). A total of 133 procedures (38 forehead impactions, 60 mandibular angle reductions, and 35 genioplasties) were performed on 45 patients (Table 1).

| Surgical technique . | Anatomical features . | No. of procedures (total = 133) . |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior frontal sinus setback | Significant frontal bossing with large projection | 38 |

| Mandibular angle resection | Large and acute mandibular angles | 60 (30 × 2) |

| Osseous genioplasty | Large chin width | 35 |

| Surgical technique . | Anatomical features . | No. of procedures (total = 133) . |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior frontal sinus setback | Significant frontal bossing with large projection | 38 |

| Mandibular angle resection | Large and acute mandibular angles | 60 (30 × 2) |

| Osseous genioplasty | Large chin width | 35 |

| Surgical technique . | Anatomical features . | No. of procedures (total = 133) . |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior frontal sinus setback | Significant frontal bossing with large projection | 38 |

| Mandibular angle resection | Large and acute mandibular angles | 60 (30 × 2) |

| Osseous genioplasty | Large chin width | 35 |

| Surgical technique . | Anatomical features . | No. of procedures (total = 133) . |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior frontal sinus setback | Significant frontal bossing with large projection | 38 |

| Mandibular angle resection | Large and acute mandibular angles | 60 (30 × 2) |

| Osseous genioplasty | Large chin width | 35 |

There was no cerebrospinal fluid leak on the forehead procedures or any infra alveolar nerve or tooth root injury on both chin and mandibular angle operations (0.0%). Infection occurred in 1 case (1/45, 2.2%) 1 month after a genioplasty, which required osteosynthesis plate removal and antibiotherapy for 21 days. There was no other complication.

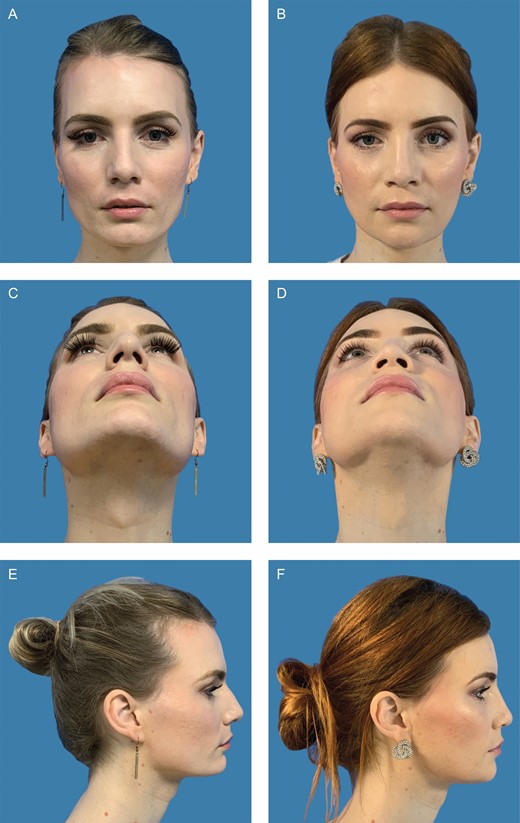

Twenty-six patients underwent the postoperative CT scan 6 months after surgery (26/45, 57.8%), allowing the analysis of 25 forehead impactions, 26 genioplasties, and 22 bilateral mandibular reductions. The accuracy was recorded at 90.80% on the forehead (n = 25; range, 72%-100%), 85.72% on the mandibular angles (n = 44; range, 63%-98%), and 96.20% on the genioplasty (n = 26; range, 79%-100%). Supplemental Figure 2 shows the 6-month postoperative CT scan compared with preoperative anatomy and preoperative virtual planning after 3D skull reconstruction. Figures 6 and 7 show examples of clinical comparison 1 year after surgery.

Clinical case of this 30-year-old patient who underwent facial feminization surgery with frontal impaction, mandibular angle resection, and genioplasty. (A) Preoperative front view. (B) Twelve-month postoperative front view. (C) Preoperative bottom view. (D) Twelve-month postoperative bottom view. (E) Preoperative side view. (F) Twelve-month postoperative bottom view.

Clinical case of this 21-year-old patient who underwent facial feminization surgery with frontal impaction, mandibular angle resection, and genioplasty. (A) Preoperative front view. (B) Twelve-month postoperative front view. (C) Preoperative side view. (D) Twelve-month postoperative side view.

All the patients presented to the 1- and 3-week postoperative consultation (45/45, 100%). Thirty-nine patients (86.7%) presented to the 3-month follow-up, whereas only 36 patients (80.0%) presented to the 6-month consultation and answered the satisfaction questionnaire. The answers were analyzed at the end of the study (Table 2).

| . | Strongly disagree % (n) . | Disagree % (n) . | Neutral % (n) . | Agree % (n) . | Strongly agree % (n) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, are your satisfied with your facial feminization? (n = 36) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5.55 (2) | 61.10 (22) | 33.3 (12) |

| Do you consider that preoperative 3D virtual planning with your surgeon enhances your understanding of facial feminization surgery? (n = 36) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 19.44 (7) | 47.23 (17) | 33.33 (12) |

| Are you satisfied with the results on the forehead compared with preoperative 3D virtual planning? (n = 32) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3.13 (1) | 15.62 (5) | 81.25 (26) |

| Are you satisfied with the results on the mandibular angles compared with preoperative 3D virtual planning? (n = 23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4.35 (1) | 21.74 (5) | 73.9 (17) |

| Are you satisfied with the results on the chin compared with preoperative 3D virtual planning? (n = 33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 42.42 (14) | 57.58 (19) |

| Would you recommend this preoperative 3D virtual planning method to your entourage desiring a facial feminization surgery? (n = 36) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11.11 (4) | 22.22 (8) | 66.67 (24) |

| . | Strongly disagree % (n) . | Disagree % (n) . | Neutral % (n) . | Agree % (n) . | Strongly agree % (n) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, are your satisfied with your facial feminization? (n = 36) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5.55 (2) | 61.10 (22) | 33.3 (12) |

| Do you consider that preoperative 3D virtual planning with your surgeon enhances your understanding of facial feminization surgery? (n = 36) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 19.44 (7) | 47.23 (17) | 33.33 (12) |

| Are you satisfied with the results on the forehead compared with preoperative 3D virtual planning? (n = 32) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3.13 (1) | 15.62 (5) | 81.25 (26) |

| Are you satisfied with the results on the mandibular angles compared with preoperative 3D virtual planning? (n = 23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4.35 (1) | 21.74 (5) | 73.9 (17) |

| Are you satisfied with the results on the chin compared with preoperative 3D virtual planning? (n = 33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 42.42 (14) | 57.58 (19) |

| Would you recommend this preoperative 3D virtual planning method to your entourage desiring a facial feminization surgery? (n = 36) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11.11 (4) | 22.22 (8) | 66.67 (24) |

3D, 3-dimensional.

| . | Strongly disagree % (n) . | Disagree % (n) . | Neutral % (n) . | Agree % (n) . | Strongly agree % (n) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, are your satisfied with your facial feminization? (n = 36) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5.55 (2) | 61.10 (22) | 33.3 (12) |

| Do you consider that preoperative 3D virtual planning with your surgeon enhances your understanding of facial feminization surgery? (n = 36) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 19.44 (7) | 47.23 (17) | 33.33 (12) |

| Are you satisfied with the results on the forehead compared with preoperative 3D virtual planning? (n = 32) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3.13 (1) | 15.62 (5) | 81.25 (26) |

| Are you satisfied with the results on the mandibular angles compared with preoperative 3D virtual planning? (n = 23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4.35 (1) | 21.74 (5) | 73.9 (17) |

| Are you satisfied with the results on the chin compared with preoperative 3D virtual planning? (n = 33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 42.42 (14) | 57.58 (19) |

| Would you recommend this preoperative 3D virtual planning method to your entourage desiring a facial feminization surgery? (n = 36) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11.11 (4) | 22.22 (8) | 66.67 (24) |

| . | Strongly disagree % (n) . | Disagree % (n) . | Neutral % (n) . | Agree % (n) . | Strongly agree % (n) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, are your satisfied with your facial feminization? (n = 36) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5.55 (2) | 61.10 (22) | 33.3 (12) |

| Do you consider that preoperative 3D virtual planning with your surgeon enhances your understanding of facial feminization surgery? (n = 36) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 19.44 (7) | 47.23 (17) | 33.33 (12) |

| Are you satisfied with the results on the forehead compared with preoperative 3D virtual planning? (n = 32) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3.13 (1) | 15.62 (5) | 81.25 (26) |

| Are you satisfied with the results on the mandibular angles compared with preoperative 3D virtual planning? (n = 23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4.35 (1) | 21.74 (5) | 73.9 (17) |

| Are you satisfied with the results on the chin compared with preoperative 3D virtual planning? (n = 33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 42.42 (14) | 57.58 (19) |

| Would you recommend this preoperative 3D virtual planning method to your entourage desiring a facial feminization surgery? (n = 36) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11.11 (4) | 22.22 (8) | 66.67 (24) |

3D, 3-dimensional.

Discussion

FFS was first introduced by Ousterhout in 1987, followed by numerous authors interested in this emerging field of surgery.2,3,5,6,15,16 The male-to-female transgender population desires, most of all, to be recognized as female in daily social interactions, making FFS a major step of their sexual reassignment.17

Surgical cutting guides are commonly utilized in maxillofacial reconstruction to enhance the safety and accuracy of the procedures, and an increasing number of surgical teams utilize preoperative planning and cutting guides for FFS procedures.7,10,11,18 In our prospective report, preoperative planning employing cutting guides seemed to be beneficial for both patient and surgeon, with good patient satisfaction and accurate procedures. Defining the osteotomy lines for the 3 main osseous procedures in FFS can be hazardous for less experienced surgeons, because there is no standardized method. On the forehead, the osteotomy lines are traditionally placed according to surgeon experience, with the risk of mispositioning, leading to intradural effraction or inappropriate aesthetic results.2,4,6,13,19,20 Some authors described how they place the osteotomy lines: Cho et al measured the sinus outlines on preoperative radiographies, and Gilde et al estimated the frontal sinus configuration perioperatively by frontal sinus transillumination.19,21 Altman6 identified the osteotomy limits on a preoperative CT scan, which is certainly more accurate than the previous methods, but the author still reported dural punctures in 5% of his patients. With a 90.80% accuracy and no intradural effraction in our forehead procedures, cutting guides seem to offer a reproducible, accurate, and safe method to perform the forehead osteotomies. Furthermore, Gray et al showed in their study on cadavers the safety improvement utilizing forehead cutting guides, with no dural effraction in the cutting guides group compared with 4 inadvertent entries in the control group.12

The commonly reported complication in mandibular angle reduction is the inferior alveolar nerve injury.7-9,22 We did not experience such complication utilizing cutting guides in our 30 bilateral mandibular angle reductions. However, we have noticed a diminished accuracy in this region (85.72% compared with 90.80% on the forehead and 96.20% on the chin). We believe that these discrepancies could be related to the fact that the forehead and chin osteotomies are performed with an open approach, unlike the mandibular angles where the approach is intraoral and the osteotomy is conducted with a 90° saw whose cutting tip is more difficult to control. Furthermore, polyamide was chosen instead of titanium for the mandibular guides because of its flexibility, which allows inserting them into a narrow space without damaging the surrounding tissues. However, there is the risk for the polyamide guide to twist and be cut by the sagittal saw, therefore rendering the osteotomies less precise and with decreased accuracy.

Although our results seem to be encouraging, there are some limitations of this study. Firstly is the absence of a control group, which could have confirmed the benefit of surgical guides in FFS. Furthermore, because all the procedures were performed by the same surgeon (Q.Q.), results should be compared in a multi-center study with those of surgeons who do not utilize VSP. Secondly was the number of patients lost to follow-up; 36 of 45 patients presented and answered the satisfaction questionnaire at 6 months postoperative, out of which only 26 underwent the postoperative CT scan. This may be explained by the fact that many of our patients come from long distances, because few centers perform FFS in France, and also that in our experience, transgender patients are part of a population for whom compliance with medical prescriptions and check-up appointments is variable. And thirdly, surgical guide manufacture is expensive and represents an additional cost that may be a limitation for common utilization. A full FFS employing cutting guides has an equivalent cost of the guides utilized for maxillofacial oncological surgery.23-25 However, self-made custom guides could be an interesting alternative to significantly reduce the cost of surgery.

Together with the physical transformation, mental preparation is also an important part of the process, because patient education could reduce preoperative anxiety.26 Preoperative planning in collaboration with the surgeon allows the patient to be fully involved in her transformation process. Transgender people suffer from social inequality and transphobic harassment in everyday life due to lack of knowledge and understanding of the population about their condition, making the doctor-patient relationship of major importance. Numerous studies show a high overall satisfaction after FFS, and ours follows the trend, with 94.40% overall satisfaction.13,15,27-29 Furthermore, 80.6% of patients reported that the planning process enhances the understanding of their surgery, and 89.89% would recommend it to anyone in their entourage desiring a FFS. However, there could be a confirmation bias in the answers due to the absence of a control group. The aim of this survey was to particularly evaluate the preoperative cooperation between the patient and her surgeon. To us, the preoperative consultation together with the patient in VSP is a crucial part of the facial feminization process.

Conclusions

This study reports the reliability of custom-made surgical cutting guides to allow a safe and accurate approach to the forehead, mandibular angles, and chin osteotomies in FFS.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

References