-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dean Jabs, Bryson G. Richards, Franklin D. Richards, Quantitative Effects of Tumescent Infiltration and Bupivicaine Injection in Decreasing Postoperative Pain in Submuscular Breast Augmentation, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 28, Issue 5, September 2008, Pages 528–533, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asj.2008.07.005

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Background: In submuscular breast augmentation, the muscle is transected along its inferior and medial border to allow the implant to rest beneath the breast mound and supply adequate cleavage. This leads to significant pain in the postoperative period.

Objective: This study was undertaken to quantitatively document the effectiveness of tumescent infiltration and bupivicaine with epinephrine injection in controlling postoperative pain in primary submuscular breast augmentation and its effect on operating time, narcotic use, and complications.

Methods: A retrospective chart review of 150 primary submuscular augmentation mammaplasties performed by 2 surgeons was conducted. Seventy-five consecutive augmentations performed by each physician during the same time period were studied. One surgeon used tumescent infiltration, using a syringe and a blunt infiltration cannula, placing 50 mL of standard tumescent solution in the planned pocket area of each breast before dissection. In addition, all cut muscle ends were injected with 0.25% bupivicaine with epinephrine (1:100,000, 40 mL per patient) under direct vision. The other surgeon omitted these steps. Patients evaluated pain subjectively using a 0 to 10 numeric pain intensity scale reported to the recovery room staff at specific times in the postanesthesia care unit.

Results: Postoperatively, the initial and discharge average pain rating was significantly different between the groups. The group that received tumescence and bupivicaine with epinephrine entered the recovery room with a significantly lower average pain score: 0.5 as compared with the pain score of the control group, which was on average 3.3. In addition, the highest average pain rating was 2.6 in the infiltrated group compared with 5.4 in the noninfiltrated group. Pain at discharge between the groups was also seen to be markedly lower with a subjective average rating of 2.0 in the infiltrated group compared with 4.0 in the control group. No difference was seen in operative time or complications.

Conclusions: This is the first report to quantitatively show a pain reduction regimen that is effective in significantly decreasing postoperative pain and decreasing the use of narcotics in the recovery room. The authors conclude that its advantages are significant, and they advocate its use in all breast augmentations.

The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery reported that augmentation mammaplasty was the most common cosmetic surgical procedure performed in women in the United States in 2007. More than 399,000 augmentations were performed in 2007 alone, up 4.1% from the previous year.1 With the recent approval of silicone gel-filled breast implants by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), there has been a substantial increase in the use of gel implants.

In an effort to decrease the rate of capsular contracture, noticeable upper pole rippling, and an abrupt transition overlying the implant, the prosthesis is often placed beneath the pectoralis major muscle. One of the drawbacks of submuscular placement, however, is that the muscle must be transected along its inferior and medial borders to allow the implant to rest beneath the breast mound and to provide adequate cleavage. This leads to significant pain in the postoperative period.2

Pain associated with any type of surgery is of great concern to patients and their physicians. The Anesthesia Departments at the University of Chicago and Duke University sampled 250 adults who had undergone surgical procedures and found that 80% had experienced acute pain after surgery. Of all concerns, pain was the concern at the top of the list for 59% of the respondents.3

Submuscular implant placement can also lead to more bleeding compared with subglandular placement. Noting that most of our patients undergoing lipoplasty experience only mild pain postoperatively and a small amount of bruising, we began to use tumescent solution infiltrated beneath the pectoralis major muscle and in the subglandular area of pocket dissection to decrease intraoperative bleeding and postoperative pain in our breast augmentation patients. In the interest of decreasing postoperative pain as much as possible, we also began to inject the pectoralis muscle that was cut with bupivicaine with epinephrine.

The effects of local anesthetic intervention in either topical or injection form on perceived pain in breast augmentation has been reported but not quantitatively studied with regard to narcotic use. Our clinical impression from patients and recovery room nurse reports was that the use of tumescent fluid and bupivicaine intraoperatively increased postoperative comfort and decreased the use of narcotics, leading to less nausea and vomiting, a more comfortable patient, and speedier discharge. It also appeared that the use of tumescent fluid decreased intraoperative bleeding. This study was undertaken to quantitatively document the effectiveness of intraoperative tumescent infiltration along with bupivicaine with epinephrine injection in controlling postoperative pain, its effects on the use of narcotics in recovery, and the possible complications in primary breast augmentation.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of 150 primary submuscular augmentation mammaplasties performed by 2 surgeons was conducted to determine if the use of tumescent infiltration and bupivicaine with epinepherine injection could provide a quantitative benefit in controlling postoperative pain and to determine if its use increased operative time and complications. Seventy-five consecutive augmentations performed by each physician, occurring during the same time period, were studied. All patients were ASA category I and underwent primary augmentations performed under general anesthesia with no other surgeries performed at the same time.

A similar amount of narcotic anesthetic was used in each group of patients during surgery. Patients ranged in age from 18 to 52 years (Table 1). The surgical technique used by both surgeons was similar in that blunt dissection was kept to a minimum, all muscle attachments were transected under direct vision using electrocautery, and all pockets were irrigated with antibiotic solution. The surgical technique differed in that 1 surgeon used tumescent infiltration, using a syringe and a blunt infiltration cannula, placing 50 mL of standard tumescent solution (1 L Ringer's lactate, 50 mL 1 % lidocaine, and 1 mL epinepherine 1:1000) in the planned pocket area of each breast before dissection. In addition, all cut muscle ends were injected with 0.25% bupivicaine with epinephrine (1:100,000, 40 mL per patient) under direct vision. The other surgeon omitted these steps. All surgeries were performed in the same outpatient surgery facility with the same anesthesiologists. All implants were from the same manufacturer (Mentor, Santa Barbara, CA) and were placed in a partial submuscular (retropectoral) pocket. The implants rested beneath the pectoralis major muscle superiorly and the breast parenchyma inferiorly. Incisions were either periareolar or in the inframammary crease. The surgeons audited each other's techniques and found them to be essentially the same. Operative times were similar.

| Control group | Tumescent infiltration and bupivicaine injection | P | |

| No. of patients | 75 | 75 | N/A |

| Tumescent infiltrate volume | None | 50 mL | N/A |

| Average implant size (mL ±SD [range]) | 357 ± 5.6 (225–600) | 352 ± 5.0 (250–630) | .53 |

| Intraoperative equianalgesic dose (mg ±SD) morphine IV | 17.8 ± 0.8 | 16.0 ± 0.9 | .11 |

| PACU time (min ±SD) | 113 ± 3.7 | 103 ± 4.9 | .11 |

| Complications | 1 hematoma, 1 infected implant | 2 hematomas | No difference in complications |

| Control group | Tumescent infiltration and bupivicaine injection | P | |

| No. of patients | 75 | 75 | N/A |

| Tumescent infiltrate volume | None | 50 mL | N/A |

| Average implant size (mL ±SD [range]) | 357 ± 5.6 (225–600) | 352 ± 5.0 (250–630) | .53 |

| Intraoperative equianalgesic dose (mg ±SD) morphine IV | 17.8 ± 0.8 | 16.0 ± 0.9 | .11 |

| PACU time (min ±SD) | 113 ± 3.7 | 103 ± 4.9 | .11 |

| Complications | 1 hematoma, 1 infected implant | 2 hematomas | No difference in complications |

PACU, Postanesthesia care unit; IV, intravenous; SD, standard deviation.

| Control group | Tumescent infiltration and bupivicaine injection | P | |

| No. of patients | 75 | 75 | N/A |

| Tumescent infiltrate volume | None | 50 mL | N/A |

| Average implant size (mL ±SD [range]) | 357 ± 5.6 (225–600) | 352 ± 5.0 (250–630) | .53 |

| Intraoperative equianalgesic dose (mg ±SD) morphine IV | 17.8 ± 0.8 | 16.0 ± 0.9 | .11 |

| PACU time (min ±SD) | 113 ± 3.7 | 103 ± 4.9 | .11 |

| Complications | 1 hematoma, 1 infected implant | 2 hematomas | No difference in complications |

| Control group | Tumescent infiltration and bupivicaine injection | P | |

| No. of patients | 75 | 75 | N/A |

| Tumescent infiltrate volume | None | 50 mL | N/A |

| Average implant size (mL ±SD [range]) | 357 ± 5.6 (225–600) | 352 ± 5.0 (250–630) | .53 |

| Intraoperative equianalgesic dose (mg ±SD) morphine IV | 17.8 ± 0.8 | 16.0 ± 0.9 | .11 |

| PACU time (min ±SD) | 113 ± 3.7 | 103 ± 4.9 | .11 |

| Complications | 1 hematoma, 1 infected implant | 2 hematomas | No difference in complications |

PACU, Postanesthesia care unit; IV, intravenous; SD, standard deviation.

Data were obtained from office charts and postoperative hospital records. The reported pain rating was a subjective response by the patient using a 0 to 10 numeric pain intensity scale reported to the recovery room staff at specific times in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). This rating of pain has been found to be valid and reliable.4 Patients in both groups were treated for postoperative pain by staff anesthesiologists at the outpatient surgery center. Different anesthesiologists used different pain medications, depending upon their experience. Patients were assigned to anesthesiologists randomly. Postoperative pain medications included morphine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, meperidine, and oycodone. Because different patients received different medications, the medication dosage was adjusted to morphine equivalents for comparison (Table 2).5

| Opioid analgesic (trade name) | Equianalgesic dose (10 mg) |

| Morphine (MS Contin, Roxanol) | 10 mg IM/IV |

| Fentanyl (Sublimaze) | 0.1 mg (100 μ) IM/IV |

| Hydrocodone (Lortab, Vicodin) | 20 mg PO |

| Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) | 1.5 mg IM/IV |

| Meperidine (Demerol) | 75 mg IM/IV |

| Oxycodone (Percocet) | 20 mg PO |

| Opioid analgesic (trade name) | Equianalgesic dose (10 mg) |

| Morphine (MS Contin, Roxanol) | 10 mg IM/IV |

| Fentanyl (Sublimaze) | 0.1 mg (100 μ) IM/IV |

| Hydrocodone (Lortab, Vicodin) | 20 mg PO |

| Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) | 1.5 mg IM/IV |

| Meperidine (Demerol) | 75 mg IM/IV |

| Oxycodone (Percocet) | 20 mg PO |

IM, Intramuscular; IV, intravenous; PO, per oral.

MS Contin is manufactured by Purdue Pharma (Cranbury, NJ).

Roxanol is manufactured by Xanodyne Pharmaceuticals (Newport, KY). Sublimaze is manufactured by Akorn Inc (Buffalo Grove, IL). Lortab is manufactured by UCB Pharma (Brussels, Belgium).

Vicodin is manufactured by Abbott Laboratories (Abbott Park, IL). Dilaudid is manufactured by Abbott Laboratories.

Demerol is manufactured by Sanofi-Aventis (Bridgewater, NJ).

Percocet is manufactured by Endo Pharmaceuticals (Chadds Ford, PA). Adapted from: American Pain Society. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain. 4th ed. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society, 1999.

| Opioid analgesic (trade name) | Equianalgesic dose (10 mg) |

| Morphine (MS Contin, Roxanol) | 10 mg IM/IV |

| Fentanyl (Sublimaze) | 0.1 mg (100 μ) IM/IV |

| Hydrocodone (Lortab, Vicodin) | 20 mg PO |

| Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) | 1.5 mg IM/IV |

| Meperidine (Demerol) | 75 mg IM/IV |

| Oxycodone (Percocet) | 20 mg PO |

| Opioid analgesic (trade name) | Equianalgesic dose (10 mg) |

| Morphine (MS Contin, Roxanol) | 10 mg IM/IV |

| Fentanyl (Sublimaze) | 0.1 mg (100 μ) IM/IV |

| Hydrocodone (Lortab, Vicodin) | 20 mg PO |

| Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) | 1.5 mg IM/IV |

| Meperidine (Demerol) | 75 mg IM/IV |

| Oxycodone (Percocet) | 20 mg PO |

IM, Intramuscular; IV, intravenous; PO, per oral.

MS Contin is manufactured by Purdue Pharma (Cranbury, NJ).

Roxanol is manufactured by Xanodyne Pharmaceuticals (Newport, KY). Sublimaze is manufactured by Akorn Inc (Buffalo Grove, IL). Lortab is manufactured by UCB Pharma (Brussels, Belgium).

Vicodin is manufactured by Abbott Laboratories (Abbott Park, IL). Dilaudid is manufactured by Abbott Laboratories.

Demerol is manufactured by Sanofi-Aventis (Bridgewater, NJ).

Percocet is manufactured by Endo Pharmaceuticals (Chadds Ford, PA). Adapted from: American Pain Society. Principles of Analgesic Use in the Treatment of Acute Pain and Cancer Pain. 4th ed. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society, 1999.

Results

The additional step of infiltrating 50 mL of tumescent solution into each pocket and injecting bupivicaine into the cut muscle did not significantly increase operative time. The amount of intraoperative pain medication given did not significantly differ between the 2 groups (17.8 equivalent units for the control group and 16 units for the treated group). The average PACU time to discharge was less with tumescent/bupivicaine infiltration by 10 minutes, but this was not statistically significant. The average implant volume placed was approximately 350 mL (225 to 630 mL). No difference in complication rates was seen between the groups (Table 1).

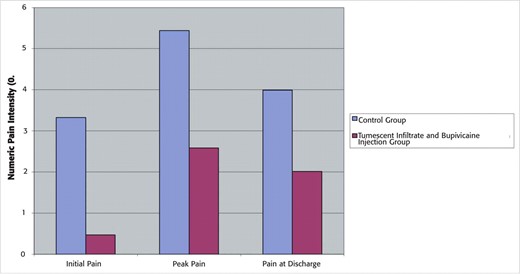

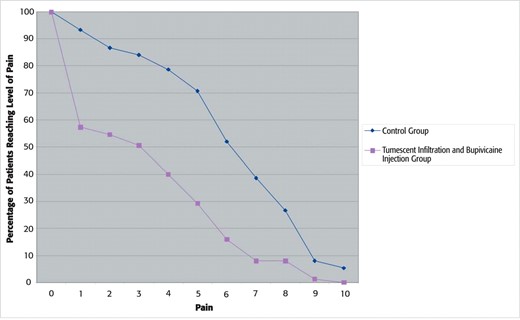

The initial and discharge average pain rating was significantly different between the groups. The group that received tumescence and bupivicaine with epinepherine entered the recovery room with a significantly lower average pain score: 0.5 as compared with the pain score of the control group, which was on average 3.3. In addition, the highest average pain rating was 2.6 in the infiltrated group compared with 5.4 in the noninfiltrated group. Pain at discharge between the groups was also seen to be markedly lower with a subjective average rating of 2.0 in the infiltrated group compared with 4.0 in the control group. All values are highly significant (P < .001; Table 1; Figure 1). The percentage of the patient population that reported each pain level can be seen in Figure 2. This graph demonstrates that the data were not skewed by a small subset of patients. The subjective patient ratings demonstrate that intraoperative intervention with tumescent infiltration and bupivicaine injection leads to markedly lower initial postoperative pain, less intense pain, and lower overall pain at discharge when compared with patients receiving no bupivicaine injection and tumescent infiltration.

Postoperative pain levels. Average postoperative pain levels recorded using a 0 to 10 numeric pain intensity scale. Three sets of pain data were analyzed: (1) initial pain upon entering the postanesthesia care unit, (2) peak pain in the postanesthesia care unit, and (3) pain reported at discharge.

Each curve shows the percentage of patients that report meeting or exceeding a given level of pain (0 to 10 on a numeric pain intensity scale).

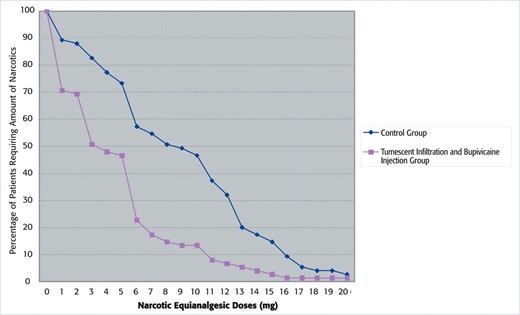

The amount of postoperative pain medication used in the recovery room was adjusted to morphine equivalents to allow for comparison between patients. The group receiving tumescent solution and bupivicaine injection was seen to require much less pain medication (4.1 morphine equivalent units as compared with 8.3 morphine equivalent units in the control group), demonstrating a greater than 50% reduction in postoperative narcotic requirement. This difference is highly significant (P < .001; Table 3). Again, when each group was evaluated to determine the percentage that required a specific morphine equivalent dose of narcotic, it is apparent that the groups did not overlap at any point nor are the means skewed by a particular subset of patients (Figure 3).

| Control group | Tumescent and bupivicaine group | Reduction | P | |

| Initial PACU pain | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 86% | <.001 |

| Peak PACU pain | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 52% | <.001 |

| Discharge PACU pain | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 50% | <.001 |

| Equianalgesic dose (mg) morphine IV in the PACU | 8.3 ± 0.6 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 51% | <.001 |

| Control group | Tumescent and bupivicaine group | Reduction | P | |

| Initial PACU pain | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 86% | <.001 |

| Peak PACU pain | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 52% | <.001 |

| Discharge PACU pain | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 50% | <.001 |

| Equianalgesic dose (mg) morphine IV in the PACU | 8.3 ± 0.6 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 51% | <.001 |

IV, Intravenous; PACU, postanesthesia care unit.

| Control group | Tumescent and bupivicaine group | Reduction | P | |

| Initial PACU pain | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 86% | <.001 |

| Peak PACU pain | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 52% | <.001 |

| Discharge PACU pain | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 50% | <.001 |

| Equianalgesic dose (mg) morphine IV in the PACU | 8.3 ± 0.6 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 51% | <.001 |

| Control group | Tumescent and bupivicaine group | Reduction | P | |

| Initial PACU pain | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 86% | <.001 |

| Peak PACU pain | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 52% | <.001 |

| Discharge PACU pain | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 50% | <.001 |

| Equianalgesic dose (mg) morphine IV in the PACU | 8.3 ± 0.6 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 51% | <.001 |

IV, Intravenous; PACU, postanesthesia care unit.

Percentage of patients that required a specific morphine equivalent narcotic dose in each group.

Discussion

As submuscular breast augmentation gains popularity, the need for a reliable method of decreasing postoperative pain becomes more important. This procedure is typically performed on an outpatient basis in which pain control requirements are different from an inpatient setting. Ideally, patients in an outpatient setting should enter the recovery room in no pain and require little if any subsequent narcotic analgesia while they awake from their general anesthetic. This allows for speedier discharge and decreases the likelihood of nausea and vomiting associated with narcotics.

Additionally, the pain control method employed should have a low complication risk and not take substantial time to administer in the operating room. Some possible methods that could meet these criteria are epidural anesthesia, synergistic oral medication, and perioperative local anesthetics administered in a variety of ways.

Lai et al6 reported using continuous epidural anesthesia to perform submuscular breast augmentation in 30 patients. The catheter was left in place until discharge, allowing more anesthetic to be administered as needed. One patient was noted to require general anesthesia. An increase in blood pressure was noted up to 30 minutes after epidural injection. Postoperative pain was well controlled, although 13% of patients experienced shortness of breath. Nesmith7 reported a similar experience in 20 patients. A 10% hypotension rate was noted. Both groups stated satisfaction with the technique, although neither presented a quantitative analysis of postoperative pain.

Methocarbamol and celecoxib have been studied for their value as oral medications to decrease perioperative pain. Schneider8 reported a nonrandomized study of 62 patients who received perioperative methocarbamol. Only 11% of the patients felt that the drug was of no benefit. Schneider observed an improvement in postoperative pain, but a quantitative method was not used. Freedman et al,9 in a well designed study, examined the effect of celecoxib on postoperative pain and the use of hydrocodone in 100 patients. Half used celecoxib and hydrocodone while the other half used hydrocodone alone for postoperative pain control. Celecoxib, a selective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), was found to significantly decrease postoperative pain and the use of hydrocodone in the first week after surgery. As expected, with less narcotic use there was less reported nausea and vomiting. Its effect in the immediate postoperative period was not discussed. The FDA has found serious adverse cardiac effects when NSAIDs of all classes (except for aspirin) are used over the long term. No such effects have been shown for celecoxib in short-term use. Patients may show reluctance to use this form of the drug because of this recent publicity.

Several authors have looked at methods of controlling postoperative pain using intra- and postoperative local medications administered directly into the surgical pocket. Hunstad10 anecdotally reported on his use of bupivicaine and its safety in breast augmentation and abdominoplasty. He applied bupivicaine topically through a red rubber catheter and noted a subjective decrease in postoperative pain and also a marked increase in postoperative pain when this step was omitted. No measurement of pain or bupivacaine was included in the report. In a letter to the editor, Papanastasiou and Evans11 reported their experience with topical bupivicaine placed in the surgical pocket via closed suction drains after completion of the procedure. The drains were clamped for approximately 10 minutes after infiltration before being unclamped. He noted “adequate” pain relief in more than 80 cases. No other analysis was provided. Peled12 anecdotally reported using tumescent infiltration in subglandular breast augmentation, describing his technique and the advantages of less bleeding and decreased pain. No data were offered to support his endorsement of tumescent infiltration. Similarly, in brief communication, Weiss13 reported using bupivicaine tumescent soaked lap sponges to pack subpectoral pockets after dissection to minimize bleeding and decrease postoperative pain. No data were provided.

Large area local anesthesia involves irrigation of the surgical pocket with dilute anesthetic, typically bupivicaine, to decrease perioperative pain. Several authors have studied this technique in a variety of surgical applications. Fredman et al14 compared 50 patients undergoing major intraabdominal surgery in a prospective, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Half received bupivicaine through a patient-controlled catheter, while the other half received placebo. The amount of rescue narcotic required in the first 6 hours after surgery was noted. No difference was found between the groups. Similarly, Johannson et al,15 in a randomized, prospective, double-blind trial, failed to observe a benefit using large area local anesthesia in partial mastectomy and axillary node dissection when using ropivacaine as the anesthetic. Nausea, vomiting, pain, and narcotic requirements were found to be similar. Parker and Charbonneau16 conducted a retrospective chart review comparing 116 patients that underwent retropectoral augmentation, approximately half of whom received pocket irrigation with 10 mL of 0.125% bupivicaine. No significant difference was found comparing nausea and vomiting, or narcotic requirement. Time to discharge was found to be less in the bupivicaine group. Pain was not measured in this study. Mahabir et al17 performed a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial in 100 patients comparing the effects of 4 solutions (normal saline, ketorolac, bupivicaine, and ketorolac with bupivicaine), placed topically into the pockets developed for implant placement. Pain was decreased in the groups containing bupivicaine for up to 90 minutes. No significant difference was noted in the use of postoperative narcotics. Theirs was the first study to document a significant effect of bupivicaine irrigation on postoperative pain. There was no statistically significant difference when ketorolac was added. No adverse reactions were seen.

Only 1 study has shown that bupivicaine irrigation is helpful in decreasing postoperative pain, while the preponderance of data indicate it is not a useful technique. Its use does not significantly decrease the use of postoperative narcotics. Topical bupivicaine application may be useful if it is left in contact with the open wound long enough to allow sufficient absorption, but this delivery method is not uniform.

We found that the intraoperative use of tumescent infiltration and bupivicaine injection with epinephrine quantitatively decreased perceived postoperative pain uniformly, at all times in the recovery room, and significantly decreased the use of postoperative pain medication in the immediate perioperative period. Patients uniformly awoke from anesthesia in less pain and were more comfortable when this regimen was used. Decreasing the amount of postoperative narcotics decreases the likelihood of nausea and vomiting. We found a trend to earlier discharge (113 vs 103 minutes) and noted that patients were more comfortable during the postoperative period.

Bupivacaine, in toxic doses, has central nervous system and cardiovascular effects. Central nervous system effects usually occur at lower doses and may include excitation (nervousness, tingling around the mouth, tremor, and blurred vision) followed by depression (drowsiness followed by loss of consciousness). Cardiovascular effects (hypotension, bradycardia, and arrhythymias) typically occur at higher doses. Both are difficult to reverse. We did not see signs of toxicity in any of our patients despite having bupivacaine injected into highly vascular muscle.

The possibility of tumescent infiltration alone being as effective as tumescent infiltration with bupivicaine injection remains to be elucidated.

Conclusions

Using a chart review analysis of 2 sets of patients, 1 with and 1 without tumescent infiltration and bupivicaine injection, we found a statistically significant difference in patient-reported postoperative pain during all phases of PACU recovery, with the control group exhibiting higher pain ratings. In addition, there was a statistically significant reduction in postoperative narcotic use and a trend to shorter recovery room stays. No significanifference in operative time or postoperative complications was noted between our 2 study groups. This is the first report to quantitatively show a pain reduction regimen that is both effective in significantly decreasing postoperative pain and the use of narcotics in the recovery room. We advocate its use in all breast augmentations.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial interest in and received no compensation from the manufacturers of products mentioned in this article.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.