-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Svenja Schäfer, Incidental News Exposure in a Digital Media Environment: A Scoping Review of Recent Research, Annals of the International Communication Association, Volume 47, Issue 2, June 2023, Pages 242–260, https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2023.2169953

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In digital news environments, incidental news exposure (INE) refers to coming across news when online for other reasons. In this systematic scoping review, conducted to summarize the current state of research on INE, I identified 88 scientific articles via Web of Science, Scopus, EBSCOhost and Google Scholar and systematically analyzed them. In quantitative analysis, trained coders coded categories such as year of publication, method, region of the sample, and the primary topic. In qualitative analysis, I summarized results for the concept of INE (e.g. definition and process of INE), its operationalization (e.g. in surveys and experiments), and published findings (e.g. determinants and effects). Finally, I articulate seven implications for future research.

The Internet is unique when it comes to distributing news to potential viewers, listeners, and readers. Digital news content is not restricted to news sites but has become a common feature on the start pages of browsers and social networking sites (SNSs), as well as is distributed via push notifications on news apps on smartphones. Those features contribute to contact with the news, or news contact, that is not initiated by users but instead occurs incidentally as a by-product of other activities. The term used for that kind of news contact, coined by Tewksbury et al. (2001), is incidental news exposure (INE).

However, the idea of INE is neither new nor restricted to online environments (Karnowski et al., 2017). Among the first to explore the idea, Downs (1957) differentiated information that people actively seek out from information that is encountered incidentally. An important difference between those types of information gathering is that people have to put effort into actively seeking information, which is not the case if information reaches them accidentally. That first explication of INE was followed by a few studies that investigated INE in offline environments such as television (Baum, 2011) and newspaper (Zukin & Snyder, 1984). Since the Internet became an established news medium, however, the occurrence of INE and scholarly interest in the topic has increased dramatically. The first study to investigate INE in an online context was conducted by Tewksbury et al. (2001), who reported mixed findings regarding the assumption that general Internet use contributes to INE and consequently affects the knowledgeability of users in a positive way.

In the past couple of years, SNSs have emerged a new way to receive news online. According to the figures of the Digital News Report for 12 countries worldwide, 36% of Internet users receive news via Facebook, followed by YouTube (21%) and WhatsApp (16%), among others (Newman et al., 2020). Even though social media is sometimes actively used as a news source, most news finds users when they visit SNSs for other reasons (Gottfried & Shearer, 2016). Thus, with the rise of social media as a channel for news, INE has become an even more widespread way to encounter news online (Kümpel, 2021). That development explains why a host of recent studies have examined various aspects of INE. In such work, scholars have highlighted the importance of having a clear conceptualization of INE (e.g. Matthes et al., 2020; Weeks & Lane, 2020), pinpointed determinants of INE (e.g. Ahmadi & Wohn, 2018; Goyanes, 2020), and shown that INE has important societal consequences for users’ civic participation (e.g. Valeriani & Vaccari, 2016) or general news consumption (e.g. Marcinkowski & Došenović, 2020; Park & Kaye, 2020).

Because INE represents a highly relevant, intensively studied phenomenon, the purpose of this study was to provide a scoping review of research on the topic. According to Munn et al. (2018), scoping reviews help to create a map of available evidence in a particular area of research, one that allows the clarification of certain concepts, demonstrates how research is conducted, and reveals gaps in knowledge based on past studies. Along those lines, the aim of this article is twofold. First, its primary goal is to analyze and synthesize studies on the quantitative and qualitative aspects of INE. Taking a broad perspective on INE, it seeks to identify what kind of research uses the label ‘INE’ in digital contexts. Such knowledge is not only highly valuable but also especially needed in such a rapidly growing field that has produced an abundance of publications that can no longer be ignored. More precisely, the scoping review serves to provide a first-of-its-kind overview of the primary concepts, types of empirical investigations, and findings concerning INE. In that light, the review should be of interest to anyone wanting to become familiar with the broader field of research on INE and/or its specific aspects, including its determinants and effects. Second, the review’s systematic approach furnishes a foundation for identifying the limitations and shortcomings of past findings as well as their implications for future research. Only when what is already known about INE in digital environments is made clear, and only if the latest developments are identified and flaws of past research considered, is it possible to make a solid contribution to the future of the field. To those ends, a review article can make a valuable contribution, especially in a field as intensively studied as INE in digital online environments.

Method

Literature identification

To identify articles that were relevant to our review, I searched for the terms ‘incidental news exposure,’ ‘incidental news consumption’ and ‘accidental news exposure’ on Web of Science, Scopus, EBSCOhost, and Google Scholar (Xiao & Watson, 2019). Those phrases had to appear in the article’s title, abstract, or keywords. On Google Scholar, pages of results were sorted by relevance, and only the first 20 pages were considered. In all, 801 articles were identified for an initial sample.

After all duplicate articles were excluded, I determined whether the remaining articles fulfilled five criteria and thus would be considered in analysis. First, as mentioned, the terms ‘incidental news exposure,’ ‘incidental news consumption,’ and/or ‘accidental news exposure’ had to appear in the title, abstract, or keywords. Articles with the phrases ‘incidental exposure’ and ‘accidental exposure’ were also considered as long as the mentioned exposure occurred in a news context. Second, articles had to address a digital news context. For example, if an article’s reported study exclusively investigated INE while watching TV, the article was excluded. If an article considered both digital and traditional media, however, then the criterion was met. We excluded articles on INE in traditional media because the prevalence, processes, and effects of INE differ greatly between different news channels. For example, when people incidentally encounter news online, they are usually confronted with teaser headlines that have to be clicked to reveal the full-length news story. When watching TV, by contrast, people usually stumble upon whatever full news stories are being aired. As a result, findings for one news channel (e.g. effects on knowledge and determinants of further news engagement) cannot be generalized to others. Because INE is most common in online environments and has attracted most scholarly attention in the digital sphere, we decided to concentrate our review on INE in digital media environments and thus excluded articles addressing other channels from our sample. Third, articles had to focus on news about current affairs and/or politics. For example, if an article’s reported study investigated incidental exposure to health information, then the article was excluded from our sample. Fourth, articles had to be published in peer-reviewed journals, which ensured that our analysis would be based on publications with the highest scientific impact and standards of quality. Fifth and last, articles had to be written in English. By applying those six criteria to the initial sample, I identified 88 articles that were relevant for further analysis, all of which are listed online (https://osf.io/qz37t/?view_only=693065e530b84982bfe462e192a9e615). The sample considers articles published, even if only online, no later than February 22, 2022.

Coding and analysis

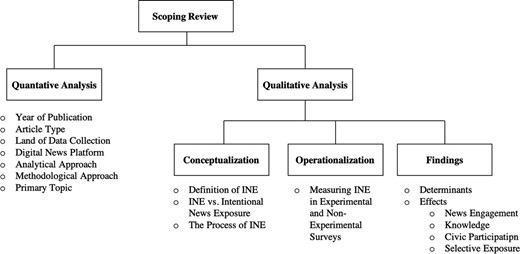

Following the example of previous systematic literature reviews (Kümpel et al., 2015; Zhang & Leung, 2015), I divided my analysis into a quantitative part and a qualitative part. In quantitative analysis, I used seven descriptive categories similar to those in the mentioned studies: (1) year of publication, (2) article type, (3) country of data collection, (4) specific digital news media platform(s) investigated, (5) analytical approach, (6) methodological approach, and (7) primary topic. The coding scheme with all categories and subcategories, the data for qualitative analysis, the data for the reliability test, and a syntax for this article can be found in the Online Appendix (https://osf.io/qz37t/?view_only=693065e530b84982bfe462e192a9e615). Coding was performed by two coders. Values for reliability were good for all categories (see Table 1) despite differences in the coding of the primary topic between the coders. However, because findings for the main topic was addressed in greater detail in our qualitative analysis, the values were considered to be acceptable.

| Category . | Krippendorf’s α . |

|---|---|

| Year | 1 |

| Article type | 1 |

| Land of data collection | 1 |

| Digital news platform | 1 |

| Analytical approach | 1 |

| Methodological approach | .91 |

| Primary Topic | .73 |

| Category . | Krippendorf’s α . |

|---|---|

| Year | 1 |

| Article type | 1 |

| Land of data collection | 1 |

| Digital news platform | 1 |

| Analytical approach | 1 |

| Methodological approach | .91 |

| Primary Topic | .73 |

| Category . | Krippendorf’s α . |

|---|---|

| Year | 1 |

| Article type | 1 |

| Land of data collection | 1 |

| Digital news platform | 1 |

| Analytical approach | 1 |

| Methodological approach | .91 |

| Primary Topic | .73 |

| Category . | Krippendorf’s α . |

|---|---|

| Year | 1 |

| Article type | 1 |

| Land of data collection | 1 |

| Digital news platform | 1 |

| Analytical approach | 1 |

| Methodological approach | .91 |

| Primary Topic | .73 |

In qualitative analysis, I considered both theoretical aspects of INE and results providing insights into the antecedents and consequences of INE. Following Loecherbach et al. (2020), I adopted the categories of conceptualization, operationalization, and findings for the analysis. An overview of the different categories and subcategories used in the quantitative and qualitative analyses appears in Figure 1.

Overview of the categories and subcategories of the scoping review.

Results

Quantitative results

An overview over all 88 articles reviewed and the codes for each category is available online (https://osf.io/qz37t/?view_only=693065e530b84982bfe462e192a9e615, file: data.final). Furthermore, Table 2 summarizes the descriptive results of the quantitative analysis of all 88 articles. Concerning the year of publication, the results indicate that although the first article on INE was published already in 2001, the topic has boomed in the past couple of years. Indeed, half of the sample was published in 2020 or 2021. Most articles report empirical studies (n = 80, 91%) that involved collecting and analyzing data, whereas the other eight articles (9%) address theoretical perspectives on INE. Most data collection took place in the United States (n = 39, 49%), followed combinations of multiple countries (n = 11, 44%) and Germany (n = 9, 11%). Concerning the platform(s) investigated, the articles’ authors showed a clear preference for social media. More than half of the reported studies investigated INE on social media in general (n = 30, 34%) or specifically on Facebook (n = 16, 18%). Meanwhile, only four of the studies examined INE on specific platforms other than Facebook: two on WhatsApp, one on TikTok, and another on YouTube. Approximately a third of the articles consider INE on ‘digital media’ (n = 24, 27%), a category coded if INE was investigated on the Internet in general or on various online outlets (e.g. INE on blogs or via email). The reported studies more often adopted quantitative approaches (n = 67, 76%) than qualitative ones (n = 11, 12%); the approach of quantitative studies was often a cross-sectional survey (n = 27, 31%) or followed a panel design (n = 20, 23%). Seven of the articles (8%) reported studies following a mixed-method design, which was coded if an article presented several empirical studies that involved different methods – for example, a combination of experiments and panel data (Heiss & Matthes, 2019a), a cross-sectional survey coupled with qualitative interviews (Bergström & Jervelycke Belfrage, 2017), and a combination of qualitative interviews, on-device log-ins, and experience sampling (Van Damme et al., 2020). Further, a minority of articles presents a theoretical framework for INE (n = 8, 9%).

| Categories . | n . | Occurrence . |

|---|---|---|

| Year | 88 | 2001 (n = 2; 2%); 2011 (n = 1; 1%); 2013 (n = 1; 1%); 2015 (n = 2; 2%); 2016 (n = 4; 5%); 2017 (n = 4; 5%); 2018 (n = 11; 12%), 2019 (n = 13; 15%); 2020 (n = 23; 26%); 2021 (n = 22; 25%); 2022 (n = 5; 6%) |

| Article type | 88 | Empirical (n = 80; 91%); Theoretical (n = 8; 9%) |

| Land of data collection | 80 | USA (n = 39; 49%); multinational (n = 11; 14%); Germany (n = 9; 11%); Austria (n = 4; 5%); Spain (n = 3; 4%); South Korea (n = 2; 2%); China (n = 2; 2%); Sweden (n = 1; 1%), Argentina (n = 1; 1%), Costa Rica (n = 1; 1%), Bangladesh (n = 1; 1%), Singapore (n = 1; 1%), Kenya (n = 1; 1%), Belgium (n = 1; 1%), Jordan (n = 1; 1%); Japan (n = 1; 1%); Cyprus (n = 1; 1%); |

| Digital news platform | 88 | Social Media (n = 30; 34%); Digital Media (n = 24; 27%); Facebook (n = 16; 18%); All Media (n = 9; 10%); News Websites (n = 4; 5%); WhatsApp (n = 2; 2%); TikTok (n = 1; 1%); News Apps (n = 1; 1%) YouTube (n = 1; 1%) |

| Analytical approach | 88 | Quantitative (n = 67; 76%); Qualitative (n = 11; 12%); Theoretical Framework (n = 8; 9%); Mixed Methods (n = 2; 2%) |

| Methodological approach | 88 | Survey (cross-sectional n = 27; 31%; longitudinal n = 20; 23%); experiment (n = 11; 12%); theoretical approach (n = 8; 9%); mixed methods (n = 7; 8%); semi-structured interviews (n = 6; 7%); other (n = 4; 5%); content analysis (n = 2; 2%); focus group interviews (n = 2; 2%); eye-tracking (n = 1; 1%) |

| Main Topic | 88 | news engagement (n = 19; 22%); other (n = 14; 16%); knowledge (n = 14; 16%); participation (n = 12; 14%); antecedents (n = 9; 10%); theoretical framework (n = 9; 10%); selective exposure (n = 8; 9%); emotional responses (n = 3; 3%) |

| Categories . | n . | Occurrence . |

|---|---|---|

| Year | 88 | 2001 (n = 2; 2%); 2011 (n = 1; 1%); 2013 (n = 1; 1%); 2015 (n = 2; 2%); 2016 (n = 4; 5%); 2017 (n = 4; 5%); 2018 (n = 11; 12%), 2019 (n = 13; 15%); 2020 (n = 23; 26%); 2021 (n = 22; 25%); 2022 (n = 5; 6%) |

| Article type | 88 | Empirical (n = 80; 91%); Theoretical (n = 8; 9%) |

| Land of data collection | 80 | USA (n = 39; 49%); multinational (n = 11; 14%); Germany (n = 9; 11%); Austria (n = 4; 5%); Spain (n = 3; 4%); South Korea (n = 2; 2%); China (n = 2; 2%); Sweden (n = 1; 1%), Argentina (n = 1; 1%), Costa Rica (n = 1; 1%), Bangladesh (n = 1; 1%), Singapore (n = 1; 1%), Kenya (n = 1; 1%), Belgium (n = 1; 1%), Jordan (n = 1; 1%); Japan (n = 1; 1%); Cyprus (n = 1; 1%); |

| Digital news platform | 88 | Social Media (n = 30; 34%); Digital Media (n = 24; 27%); Facebook (n = 16; 18%); All Media (n = 9; 10%); News Websites (n = 4; 5%); WhatsApp (n = 2; 2%); TikTok (n = 1; 1%); News Apps (n = 1; 1%) YouTube (n = 1; 1%) |

| Analytical approach | 88 | Quantitative (n = 67; 76%); Qualitative (n = 11; 12%); Theoretical Framework (n = 8; 9%); Mixed Methods (n = 2; 2%) |

| Methodological approach | 88 | Survey (cross-sectional n = 27; 31%; longitudinal n = 20; 23%); experiment (n = 11; 12%); theoretical approach (n = 8; 9%); mixed methods (n = 7; 8%); semi-structured interviews (n = 6; 7%); other (n = 4; 5%); content analysis (n = 2; 2%); focus group interviews (n = 2; 2%); eye-tracking (n = 1; 1%) |

| Main Topic | 88 | news engagement (n = 19; 22%); other (n = 14; 16%); knowledge (n = 14; 16%); participation (n = 12; 14%); antecedents (n = 9; 10%); theoretical framework (n = 9; 10%); selective exposure (n = 8; 9%); emotional responses (n = 3; 3%) |

| Categories . | n . | Occurrence . |

|---|---|---|

| Year | 88 | 2001 (n = 2; 2%); 2011 (n = 1; 1%); 2013 (n = 1; 1%); 2015 (n = 2; 2%); 2016 (n = 4; 5%); 2017 (n = 4; 5%); 2018 (n = 11; 12%), 2019 (n = 13; 15%); 2020 (n = 23; 26%); 2021 (n = 22; 25%); 2022 (n = 5; 6%) |

| Article type | 88 | Empirical (n = 80; 91%); Theoretical (n = 8; 9%) |

| Land of data collection | 80 | USA (n = 39; 49%); multinational (n = 11; 14%); Germany (n = 9; 11%); Austria (n = 4; 5%); Spain (n = 3; 4%); South Korea (n = 2; 2%); China (n = 2; 2%); Sweden (n = 1; 1%), Argentina (n = 1; 1%), Costa Rica (n = 1; 1%), Bangladesh (n = 1; 1%), Singapore (n = 1; 1%), Kenya (n = 1; 1%), Belgium (n = 1; 1%), Jordan (n = 1; 1%); Japan (n = 1; 1%); Cyprus (n = 1; 1%); |

| Digital news platform | 88 | Social Media (n = 30; 34%); Digital Media (n = 24; 27%); Facebook (n = 16; 18%); All Media (n = 9; 10%); News Websites (n = 4; 5%); WhatsApp (n = 2; 2%); TikTok (n = 1; 1%); News Apps (n = 1; 1%) YouTube (n = 1; 1%) |

| Analytical approach | 88 | Quantitative (n = 67; 76%); Qualitative (n = 11; 12%); Theoretical Framework (n = 8; 9%); Mixed Methods (n = 2; 2%) |

| Methodological approach | 88 | Survey (cross-sectional n = 27; 31%; longitudinal n = 20; 23%); experiment (n = 11; 12%); theoretical approach (n = 8; 9%); mixed methods (n = 7; 8%); semi-structured interviews (n = 6; 7%); other (n = 4; 5%); content analysis (n = 2; 2%); focus group interviews (n = 2; 2%); eye-tracking (n = 1; 1%) |

| Main Topic | 88 | news engagement (n = 19; 22%); other (n = 14; 16%); knowledge (n = 14; 16%); participation (n = 12; 14%); antecedents (n = 9; 10%); theoretical framework (n = 9; 10%); selective exposure (n = 8; 9%); emotional responses (n = 3; 3%) |

| Categories . | n . | Occurrence . |

|---|---|---|

| Year | 88 | 2001 (n = 2; 2%); 2011 (n = 1; 1%); 2013 (n = 1; 1%); 2015 (n = 2; 2%); 2016 (n = 4; 5%); 2017 (n = 4; 5%); 2018 (n = 11; 12%), 2019 (n = 13; 15%); 2020 (n = 23; 26%); 2021 (n = 22; 25%); 2022 (n = 5; 6%) |

| Article type | 88 | Empirical (n = 80; 91%); Theoretical (n = 8; 9%) |

| Land of data collection | 80 | USA (n = 39; 49%); multinational (n = 11; 14%); Germany (n = 9; 11%); Austria (n = 4; 5%); Spain (n = 3; 4%); South Korea (n = 2; 2%); China (n = 2; 2%); Sweden (n = 1; 1%), Argentina (n = 1; 1%), Costa Rica (n = 1; 1%), Bangladesh (n = 1; 1%), Singapore (n = 1; 1%), Kenya (n = 1; 1%), Belgium (n = 1; 1%), Jordan (n = 1; 1%); Japan (n = 1; 1%); Cyprus (n = 1; 1%); |

| Digital news platform | 88 | Social Media (n = 30; 34%); Digital Media (n = 24; 27%); Facebook (n = 16; 18%); All Media (n = 9; 10%); News Websites (n = 4; 5%); WhatsApp (n = 2; 2%); TikTok (n = 1; 1%); News Apps (n = 1; 1%) YouTube (n = 1; 1%) |

| Analytical approach | 88 | Quantitative (n = 67; 76%); Qualitative (n = 11; 12%); Theoretical Framework (n = 8; 9%); Mixed Methods (n = 2; 2%) |

| Methodological approach | 88 | Survey (cross-sectional n = 27; 31%; longitudinal n = 20; 23%); experiment (n = 11; 12%); theoretical approach (n = 8; 9%); mixed methods (n = 7; 8%); semi-structured interviews (n = 6; 7%); other (n = 4; 5%); content analysis (n = 2; 2%); focus group interviews (n = 2; 2%); eye-tracking (n = 1; 1%) |

| Main Topic | 88 | news engagement (n = 19; 22%); other (n = 14; 16%); knowledge (n = 14; 16%); participation (n = 12; 14%); antecedents (n = 9; 10%); theoretical framework (n = 9; 10%); selective exposure (n = 8; 9%); emotional responses (n = 3; 3%) |

By topic, most articles address INE and news engagement (n = 19, 22%), coded as such if the authors examined INE in the general context of practices of political news use or INE’s effects on news engagement. For example, several articles for which news engagement was coded as the primary topic address what makes users click on news posts that they come across on social media (Kaiser et al., 2018; Karnowski et al., 2017; Kümpel, 2019a). Other frequent topics were INE’s effects on knowledge (n = 14, 16%) and civic participation (n = 12, 14%), the latter coded if articles address how INE relates to activity in the democratic process – for example, voting, participating in demonstrations, contacting politicians, and engaging in political discussions. All of those areas of research and their key findings were further examined in the qualitative analysis.

Qualitative results

In our qualitative analysis, we examined articles in relation to three categories: conceptualization, operationalization, and findings.

Conceptualization

To elucidate current understandings of INE, I systematically analyzed theoretical aspects of the concept. An initial result was that most of the theoretical reflections provided in the articles can be assigned to one of three subcategories: the definition of INE, INE versus intentional news exposure, and the process of INE.

Definition of INE. The most common definition of INE conceives it as the process of encountering news without actively seeking it (Tewksbury et al., 2001). Put differently, scholars refer to INE if users come into contact with news while they are online for other reasons (Antunovic et al., 2017; Fletcher & Nielsen, 2018; Kim et al., 2013; S. Lee, 2018; Matthes et al., 2020; Van Damme et al., 2020). If these other reasons are not news related, this is referred to as intention-based INE (Yadamsuren & Erdelez, 2011). For example, an Internet user may go online to find a restaurant’s hours but end up reading a story that was teased in a headline of the browser’s start page. Another form of INE that has received less attention is finding news serendipitously while looking up another news topic (Ahmadi & Wohn, 2018; Antunovic et al., 2017; Yamamoto & Morey, 2019), which is referred to as topic-based INE (Yadamsuren & Erdelez, 2011). According to Matthes et al. (2020), the different initial goals that precede INE might be relevant to the process of INE (e.g. for elaboration and scanning) and, in turn, INE’s outcomes (e.g. learning from INE). Characteristic of both intention-based and topic-based INE is that costs of time and effort spent on finding news are rather low because users do not need to invest any kind of resources in advance of the news encounters (Downs, 1957).

Another characteristic of INE is its deep roots in research on social media and news exposure. As such, INE is most often investigated in a social media context (see Table 1) and assumed to be a common way of encountering news posts in those settings (Feezell & Ortiz, 2019; Heiss & Matthes, 2019b; Kaiser et al., 2018; Karnowski et al., 2017; Müller & Schulz, 2019). In multiple studies, using SNSs as a source for news was even equated with experiencing INE (Kümpel, 2019a; Müller & Schulz, 2019), meaning that some articles investigating news exposure on social media nevertheless use the designation ‘INE.’ That trend can be explained by findings showing that motivations for using SNSs do not always relate to learning about current events but rather to be entertained or engage in social activity (Ekström et al., 2014; Quan-Haase & Young, 2010). Beyond that, the Pew Research Center has shown that 62% of users exposed to news on Facebook reported that the news encounters mostly happened when they were online for other reasons (Gottfried & Shearer, 2016). Those findings indicate that although a great share of news exposure on SNSs seems to happen accidentally, some users intentionally visit their profiles to access news content.

INE Versus Intentional News Exposure. Another important aspect of the concept of INE is its distinction from intentional news exposure. Early on, Downs (1957) argued that people can either acquire information purposefully as a result of a rational calculus or passively obtain information incidentally. In several studies reported in the articles in our sample, researchers have adapted those bipolar modes of news exposure for digital environments, either to explain the concept of INE (Borah et al., 2022; Karnowski et al., 2017; Kümpel, 2019a; Valeriani & Vaccari, 2016) or to investigate whether outcomes vary depending on incidental or intentional news contact (Kwak et al., 2020; S. Lee, 2018; Marcinkowski & Došenović, 2020). Concerning the question of how INE and intentional news exposure relate to each other, Mitchelstein et al. (2020) have provided qualitative data demonstrating that they occur on a continuum and thus that there are practices on both extremes, namely whether users have full control of their news choices (i.e. most intentional) or whether news finds them when they do not expect it whatsoever (i.e. most incidental). Of course, between those extremes are hybrid patterns of INE – for instance, when users create an environment in which news can easily reach them, including by following news outlets on social media and installing a news app with regular push notifications (cf. Kümpel, 2020; Thorson, 2020). Viewing INE as a continuum, Van Damme et al. (2020) have shown in their qualitative findings that INE can be conceptualized according to the level of users’ agency and differentiated into a responding, a monitoring, and a browsing type of INE. While responding is completely passive – for instance, when users receive an alert or a push notification – whereas monitoring results from surveillance actions such as installing news apps. By contrast, browsing describes finding unexpected topics while consciously looking for news.

The Process of INE. Another stream of recent literature provides further insights into the process of INE. Therein, several articles indicate the importance of differentiating incidental news contact from INE (Kaiser et al., 2018; Marcinkowski & Došenović, 2020; Matthes et al., 2020). Incidental contact refers to random encounters with news – for example, if news appears in one’s news feed – whereas incidental exposure also refers to processing and engaging with news (Marcinkowski & Došenović, 2020). That same distinction is central in the political incidental news exposure model (PINE) developed by Matthes et al. (2020), according to which INE is a dynamic process that begins with the passive scanning (i.e. the first level of INE) of encountered news content that reaches users accidentally. If the user appraises the content as being relevant, then they commence their intentional processing (i.e. the second level of INE) of the content. As a result, the goals of processing change, for users develop a motivation to expose themselves to the content that they found to be relevant. The outcome of appraising relevance depends on individual factors, message and source factors, and situational factors. The PINE model emphasizes that INE’s effects (e.g. on knowledge and civic participation) depend far more on the second than the first level of INE, which thus highlights the importance of considering both phases in empirical investigations of INE. Another theoretical model developed by Wieland and Kleinen-von Königslöw (2020) conceptualizes the outcome of INE with a triple path model. In their article, the authors delve deeper into the phase of being exposed to INE and describe three scenarios, or paths, that might follow incidental news contact. In Path A (i.e. automatic scrolling through one’s news feed), the user remains rather passive and habitually scrolls their news feed, with their attention directed to the feed as a whole but not any posts in particular. As a consequence, the (news) content is processed unconsciously. Path B (i.e. conscious encounters with news on a teaser level) describes the process of so-called news snacking. In that scenario, the user consciously perceives news posts, but their attention is driven by the specific content in a decidedly bottom – up fashion. However, users on that path do not click on posts and thus only receive a limited amount of information about a given news topic. Last, on Path C (i.e. active engagement with full articles), news posts encountered by accident exceed the user’s relevance threshold, which results in an episode of conscious, attentive news use with full-length articles.

Operationalization

The most common way of measuring INE in survey studies reported in articles in this sample has been with an item developed by Tewksbury et al. (2001), namely ‘When you go online, do you ever encounter or come across news and information on current events, public issues, or politics when you may have been going online for a purpose other than to get the news?’ Several studies have used that type of measurement (Ahmed & Gil-Lopez, 2022; Ardèvol-Abreu et al., 2019; Borah et al., 2022; Fletcher & Nielsen, 2018; Kim et al., 2013; J. K. Lee & Kim, 2017; S. Lee, 2018; S. Lee & Xenos, 2020; Oeldorf-Hirsch, 2018; Park & Kaye, 2020; Valeriani & Vaccari, 2016; Yoo & Gil De Zúñiga, 2019) or else used items with similar wordings that also ask about news encounters when doing other things online (Goyanes, 2020; Oeldorf-Hirsch, 2018), being online for other reasons (Fletcher & Nielsen, 2018; Marcinkowski & Došenović, 2020), or finding news accidentally (Lu & Lee, 2019; Weeks et al., 2017). Although that single-item measure has been used in most studies, a three-item measure has also been used that inquires into INE (Heiss et al., 2019), in which respondents are asked whether they ‘(1) stumble upon news only by accident, (2) only see political posts when other people from their network post about politics, and (3) do not seek political information, but sometimes see political information by accident’ (Nanz et al., 2020, p. 243). When using the single – and three-item measures, researchers have most frequently relied on 5 – or 7-point scale ranging from never to very often (e.g. Barnidge, 2020; Heiss & Matthes, 2019a; S. Lee, 2018; Marcinkowski & Došenović, 2020; Valeriani & Vaccari, 2016). Meanwhile, other scholars have asked participants about how frequently they use SNSs as a source for news, namely as indicator of INE (Heiss & Matthes, 2019a; Müller & Schulz, 2019; Scharkow et al., 2020). By contrast, Karnowski et al. (2017) adopted a somewhat unusual way of measuring INE in a survey study; they applied mobile forced experienced sampling, meaning that participants were asked on a daily basis to open their Facebook news feed, look at the most recent news post, and answer questions about the post in a subsequent survey.

Another line of literature accounts for attitude consistency in experiences with INE. In those studies, authors have asked participants how often they have accidentally encountered information that challenged their preexisting attitudes – for example, by being critical of their supported candidate or disagreeing with their political views (Kwak et al., 2020; Lu & Lee, 2019; Weeks et al., 2017).

In experimental studies, INE has mostly been induced by confronting participants with a news feed (Heiss & Matthes, 2019a; Kaiser et al., 2018; Mothes & Ohme, 2019; Vraga et al., 2019) or a website (J. K. Lee & Kim, 2017; March et al., 2016). Exceptions include studies by Feezell (2018) and Feezell and Ortiz (2019), who investigated INE’s effects on agenda setting and knowledge with the Facebook group function. More precisely, the authors established a Facebook group, regularly published news posts in the group, and conducted a pre – and post-test survey. Another innovative experimental design was developed by Stroud et al. (2020); therein, participants in the experimental condition had to download real news apps and regularly received push notifications, for a form of encounters that served as INE.

Findings

The findings of quantitative, qualitative, and theoretical studies in the articles investigating INE can be clustered into determinants and effects.

Determinants of INE. A great deal of articles addressing INE provide theoretical reflections or findings on antecedents of INE. As for theoretical findings, Weeks and Lane’s (2020) ecological model takes a broad, holistic perspective on INE and maps factors that the authors consider to be crucial for the causes of, experiences with, and effects of INE. Those factors are categorized at six ecological levels – media systems and social networks for environmental factors and motivation, environmental perception, identity/demographic, and cognitive for individual factors – and differentiate between trait and state factors.

In the context of social media, Thorson and Wells’s (2016) curated flows framework maintains that news encounters can be considered to result from curation processes. More precisely, it identifies journalistic curation, strategic curation, personal curation, social curation, and algorithm curation as the determinants of processes of news exposure. Because individual interests and behaviors play an important role in processes related to personal, social, and algorithmic curation, it is plausible that INE is more likely to occur for some than for others. Indeed, according to Kümpel (2020), a Matthew effect is likely for both incidental news encounters and engagement with news found by accident. Because news feeds are personalized based on both user behavior and an algorithmically driven recommendation system that is itself based on personal preferences, information-rich users are the most likely to get richer in SNS environments. In fact, findings suggest that individuals with more political interest and intention to interact with news posts also exhibit more news-boosting behavior, while ones who want to avoid news about current affairs put effort into limiting the amount of news posts that they see on social media (Merten, 2020). As a result of that dynamic, users with a generally high affinity for news are also more likely to come into contact with news posts on SNSs and, in turn, to engage with news topics, whereas their peers with little interest in news do not see as much news-related content on their social media pages. Altogether, the gap between the information-rich and the information-poor should widen as a result of INE (Kümpel, 2020).

Aside from those theoretical reflections, quantitative empirical findings have provided additional insights into determinants of INE. Concerning sociodemographic variables, Tewksbury et al. (2001), Scheffauer et al. (2021), and Barnidge and Xenos (2021) have shown in cross-sectional surveys that age is negatively related to INE, although the effect size has been moderate to rather small. Tewksbury et al. (2001) reported an unstandardized logistic regression coefficient of b = -.03 in wave 1 and b = -.02 in wave 2, Scheffauer et al. (2021) found a standardized ordinary least squares regression coefficient of ß = .11, and Barnidge and Xenos reported a standardized ordinary least square coefficient of ß = -.26. Although Serrano Puche et al. (2018), following the same methodological approach, found that age is a strong positive predictor of INE, other studies investigating the role of age with cross-sectional or longitudinal surveys could not confirm any such relationship (Ahmadi & Wohn, 2018; Goyanes, 2020; Heiss & Matthes, 2019b; J. K. Lee & Kim, 2017; Lu & Lee, 2019). Concerning gender, the findings have been similar. Although studies have indicated that women are more likely than men to be accidentally exposed to news content (Goyanes, 2020; Lu & Lee, 2019), the relationships were rather weak. For instance, in their panel study, Lu and Lee (2019) found an unstandardized coefficient of ß = −.79, which reaches only a marginal level of significance (p < .10). Beyond that, most other studies have not revealed any relationship between gender and the frequency of INE (Heiss & Matthes, 2019b; J. K. Lee & Kim, 2017; Scheffauer et al., 2021; Serrano Puche et al., 2018; Tewksbury et al., 2001). As for level of education, Lu and Lee (2019) found a rather weak negative relationship, while Goyanes’s (2020) cross-sectional survey revealed a weak positive relationship. Various other studies have shown no relationship between level of education and INE (Ahmadi & Wohn, 2018; J. K. Lee & Kim, 2017; Serrano Puche et al., 2018; Tewksbury et al., 2001). Concerning income, both Goyanes (2020) and J. K. Lee and Kim (2017) found a weak negative relationship with INE, whereas most other studies have been able to confirm any relationship between income and INE whatsoever (Ahmadi & Wohn, 2018; Lu & Lee, 2019; Serrano Puche et al., 2018; Tewksbury et al., 2001). In sum, those inconclusive findings regarding the role of sociodemographic variables in INE suggest that such variables do not especially determine the frequency of INE. Moreover, taking all of those studies into consideration, we can conclude that studies with longitudinal designs are especially unable to confirm that sociodemographic variables matter for INE. Still, the different findings might also be due to differences of the sample under study, for example with regard to the country where the study was conducted, the time of data collection or the specific groups of people that were investigated in the different studies that have been summarized in this paragraph.

Another cluster of independent variables concerns media use. Regarding traditional news use, Lu and Lee (2019) found no relationship with INE, whereas Goyanes (2020) found a weak negative relationship, and, by further contrast, both Scheffauer et al. (2021) and Barnidge and Xenos (2021) found a weak positive relationship between traditional news exposure and the frequency of INE. Even though all of those studies involved using the same method (i.e. cross-sectional survey), their findings differed. Results on using the Internet to access news have also been mixed (Goyanes, 2020; Scheffauer et al., 2021; Tewksbury et al., 2001). Concerning SNSs, several studies have shown a positive relationship between the frequency of SNS or Facebook use to find news and INE (Ahmadi & Wohn, 2018; Goyanes, 2020; S. Lee, 2018; Lu & Lee, 2019; Scheffauer et al., 2021). Effect sizes found for that relationship have ranged from weak to medium. Although J. K. Lee and Kim (2017) found no relationship between general SNS use and INE, they did find that the number of weak ties and network diversity positively affect the frequency of INE, which aligns with findings from Ahmadi and Wohn (2018) and Lu and Lee (2021). At the same time, the motivation for using SNSs seems to play a role as well. According to Heiss et al. (2019), using SNSs for entertainment purposes positively affects the amount of INE.

Although sociodemographic variables and media use have been the most frequently investigated predictors of INE, two other variables also considered have been political interest and political ideology. Concerning political interest, published findings indicate its positive relationship with INE (Lu & Lee, 2019; Serrano Puche et al., 2018). An exception, however, is the study by Barnidge and Xenos (2021) that did not confirm such a relationship. Regarding political ideology, results are once again mixed. Whereas Goyanes (2020) could not confirm political ideology’s relationship with INE, J. K. Lee and Kim (2017) found that INE was more likely for conservatives than liberals, while Serrano Puche et al. (2018) found a U-shaped relationship between political ideology and INE in Argentina, Chile, Spain, and Mexico – that is, more extreme ideologies were related to less INE.

Effects of INE. Regarding the effects of INE, most studies in the sampled articles focused on one of four bearers of those effects: news engagement, civic participation, knowledge, and selective exposure.

News engagement

The literature on news engagement can be separated into two streams. The first investigates what makes people click on the teaser headlines that they incidentally encounter in digital environments, whereas the second asks how INE and the use of other (traditional) news sources relate to each other. Concerning the first, experimental studies (Kaiser et al., 2018; Karnowski et al., 2017) and qualitative findings (Kümpel, 2019a) have indicated that if a friend (i.e. a strong tie) shares a news post, then the likelihood of clicking on the post increases. However, the effect size was rather small, at least in Karnowski et al.’s (2017) study. Furthermore, if a person is tagged in a news post (Kümpel, 2019b) or receives a news story through a private message from a friend (Kümpel, 2019a), then the likelihood that they will follow the link provided and engage with the full news story increases as well. Aside from the role of personal contacts, how users perceive the topic of posts has also been investigated, and findings of both a qualitative study (Kümpel, 2019a) and an experimental survey (Karnowski et al., 2017) have confirmed that if a person is already interested in a topic, then they are more likely than otherwise to click on posts in their news feed that address the topic. That effect proved to be rather strong, especially compared with the role of the personal connection with whoever shares the news (Karnowski et al., 2017). Beyond that, in their experimental study Mothes and Ohme (2019) found that preexisting attitudes play a role in whether people click on news posts. In particular, when participants had an intention to vote for a particular party, they were less likely than otherwise to not click on posts containing criticism of the party. However, that effect surfaced only when the articles did not contain social cues. Last, the source of the news post also seems to play a role. If news posts are from trusted sources (e.g. legacy publications compared with tabloids), then the likelihood of clicking on the posts also increase (Kaiser et al., 2018).

When it comes to INE and general news use, the sampled articles report both positive and negative outcomes. Concerning positive effects, studies have confirmed that INE increases online (political) information seeking or time spent with news (Oeldorf-Hirsch, 2018; Strauß et al., 2020; Stroud et al., 2020; Yamamoto & Morey, 2019). That finding is highly consistent among studies that have applied a variety of methods, including cross-sectional and longitudinal designs as well as experimental surveys. Moreover, people who report more INE have been found to use a wider variety of sources to access news online, both in a cross-sectional survey (Fletcher & Nielsen, 2018) and in a log file analysis (Scharkow et al., 2020). Concerning negative effects, by contrast, in their recent two-wave panel study Park and Kaye (2020) found that INE’s negative effect on general news use was mediated by the ‘news-finds-me’ perception. That means that frequent INE contributes to the perception that news will reach users even when they do not actively seek it out (Strauß et al., 2021), which decreases their deliberate use of online and traditional news media (Park & Kaye, 2020). For another reason why general news use decreases as a result of INE, Marcinkowski and Došenović (2020) found in their cross-sectional survey that if unwanted information incidentally reached users, then they developed reactance that consequently increased their avoidance of the news.

Knowledge

Another branch of literature investigates INE’s outcomes for knowledge. The question of whether and, if so, then how INE affects the knowledgeability of people who accidentally encounter news was addressed in the very first study investigating INE in a digital context. Tewksbury et al. (2001) used cross-sectional data from the Pew Research Center representing three points in time and observed for one of the time points that INE was a rather weak positive predictor of knowledge about current affairs. Thus, they found only mixed support for the assumption that INE exerts positive effects on the knowledgeability of users. In a recent experimental study on that relationship, Stroud et al. (2020) also found mixed results. While investigating whether receiving push notifications from a news app improved performance on a knowledge test, they confirmed that effect of push messages for one of the two apps that they examined. Although those studies have pinpointed INE’s at least partly positive effect on knowledge, Feezell and Ortiz (2019) could not confirm that relationship. In their two experimental studies using the Facebook group function, participants received political news posts in the experimental condition or non-political content in the control condition. The results of both experiments revealed that INE did not affect knowledge because performance on the test was approximately the same in both groups. However, the second experiment showed that the number of ‘Don’t know’ answers decreased in the political posts condition among participants with low political interest. That result indicates that some people in the condition had a feeling of increased knowledge even though their knowledge had not in fact increased.

Recent findings have also indicated that incidental news contact should be differentiated from INE. Concerning news contact, a qualitative study revealed that INE seems to make people rather aware of topics and gives them a superficial idea of what is happening in the world (Goyanes & Demeter, 2020). Meanwhile, a panel survey (S. Lee et al., 2022) and a cross-sectional survey (Anderson et al., 2021) showed that such contact does not increase knowledge and that positive outcomes for knowledge can be expected only if users also engage with the snippet of news that they incidentally found. Both a cross-sectional survey study (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2021) and experimental findings (Heiss & Matthes, 2019a; J. K. Lee & Kim, 2017) have indicated that for INE to positively affect knowledge, it is necessary that people engage with the linked news content and thoroughly elaborate the information provided. Those results show that INE’s effects on knowledge do not depend solely on encounters with news but also on how users engage and process the news that they have found incidentally.

But what determines further engagement with news? An experimental study has shown that if the news content is perceived to be relevant, then people click more often on the news content and, in turn, gain knowledge (Nanz & Matthes, 2020). Findings from a cross-sectional survey have also revealed that if users confront content that they do not want, then they experience reactance, which increases their news avoidance and negatively affects their knowledge (Marcinkowski & Došenović, 2020). However, unexpected news encounters with desired content decrease news avoidance, which mediates positive outcomes for knowledge. Other recent findings have indicated that INE’s effects on knowledge may be moderated; such effects are likely if people have a heterogeneous news feed (Anderson et al., 2021), have a network that consists of diverse people, and show higher levels of social and institutional trust (Hopp et al., 2020). Another moderator is political interest, for INE’s effects on knowledge have been strongest for people with low political interest (Weeks et al., 2022), meaning that INE could narrow gaps in knowledge in society. Beyond that, when socioeconomic status has been treated as a moderator, as was the case in a several cross-sectional survey, gaps in knowledge also diminish (Morris & Morris, 2017).

Whereas all of those studies have focused on knowledge consisting of verifiable facts, INE might also increase the likelihood of coming into contact with disinformation. Qualitative findings have indicated that when people receive news via WhatsApp, they are not always sure whether the information is true or false (Masip et al., 2021). The quantitative findings of Borah et al. (2022) imply that INE can indeed increase misperceptions. In their cross-sectional study conducted in the United States, INE across online and offline media was positively related with misperceptions in general and misperceptions related to the COVID – 19 pandemic in particular.

Civic participation

Although some of our sampled articles do not confirm any effect of INE on civic participation based on cross-sectional studies (Heiss et al., 2019; S. Lee, 2018) and a panel study (Nanz et al., 2020), many other scholars have reported such a relationship in panel studies (Heiss & Matthes, 2019b; S. Lee & Xenos, 2020; Yamamoto & Morey, 2019) as well as cross-sectional surveys (Kim et al., 2013; Valeriani & Vaccari, 2016). A recent meta-analysis has also confirmed a positive relationship between INE and civic participation (Nanz & Matthes, 2022) and that effects are significantly stronger for online than for offline participation, even if they were substantially less in panel studies than in cross-sectional surveys (Nanz & Matthes, 2022). Those findings indicate that INE might have positive outcomes for a democracy that depends on the active engagement of citizens. Even so, other findings suggest that people might not benefit equally from those positive effects. A cross-sectional survey showed that INE’s effects on civic participation were stronger for respondents who reported using the Internet less for entertainment purposes than for respondents using the Internet mostly for entertainment (Kim et al., 2013). Another study applying a similar methodological approach revealed that for people with little political interest, INE has positive outcomes for types of civic participation requiring little effort (Valeriani & Vaccari, 2016), while people with great interest in politics engage more in effort-intensive forms of civic participation precisely due to INE (Heiss & Matthes, 2019b). Other findings indicate that INE even discourages civic participation among people with low political interest (Ahmed & Gil-Lopez, 2022). Thus, INE seems to widen gaps between users with high political interest who use the Internet also to get informed and those with low interest in politics who mainly spend their time online with entertaining activities.

Whereas those studies have investigated the direct or moderated effects of INE on civic participation, other studies have indicated that the relationship might be mediated – for example, by anxiety when moderated by issue relevance (Lu, 2019), heterogeneous discussions (Yoo & Gil De Zúñiga, 2019), online political information seeking and online political expression (Yamamoto & Morey, 2019), and news elaboration (Shahin et al., 2020).

Selective exposure

Because INE provides users with information that they did not (entirely) choose to access, it might also have the potential to increase encounters with cross-cutting content. Indeed, findings indicate that users incidentally come into contact with cross-cutting content on social media (Lu & Lee, 2019; Masip et al., 2021), pay visual attention to such content (Vraga et al., 2019), and remember attitude-challenging content in their news feeds (Lu & Lee, 2019). However, when not only exposure but also engagement with news is considered, INE with counter-attitudinal information might also contribute to stronger selective exposure tendencies. A panel survey has shown that incidental exposure to counter-attitudinal information seems to motivate people to actively seek or engage with content that matches their preexisting preferences, as has also been shown for attitudinal stances (Weeks et al., 2017) and in regard to political parties (Mothes & Ohme, 2019). Concerning polarization, Sude et al. (2019) found in their experiment that encounters with cross-cutting content increased polarized attitudes. However, those findings seem to depend on whether the content is only scanned, in which case polarized attitudes seem to increase; however, if the content is actively elaborated, then INE lowers polarized attitudes but only among people who think that the information is useful (Chen et al., 2021). Another experimental study revealed that INE affects corrective participation via negative emotional reactions, which is particularly strong among people who perceive the topics in question to be relevant (Lu, 2019). Added to that, INE is also related to contributing to cross-cutting online discussions, albeit in a curvilinear way (Kwak et al., 2020). Thus, finding cross-cutting information seems to incidentally have both positive and negative outcomes for selective exposure, polarization, and civic participation.

Discussion and outlook

INE, or when users come into contact with news without actively seeking it, has become a booming research topic in recent years. The Internet has made it easier for news to find users instead of the other way around. Because the number of studies investigating INE has created a broad field of research, with this article I aimed to provide a scoping review of relevant literature. Both quantitative and qualitative aspects were considered; whereas the chief quantitative findings related to descriptive statistics (e.g. year of publication and methodological approach), the conceptualization, operationalization, and findings of INE were examined in a qualitative analysis. At the same time, this article’s aim is not solely to summarize previous work but also to identify gaps in research and directions for future scientific investigations into INE. To that purpose, in the following subsections I propose seven implications of the findings of our scoping review.

Implication 1: different levels, different outcomes

Incidentally coming into contact with news online can mean many different things. For example, news contact can precede briefly reading a headline or reading a full-length news article, followed by an extensive search for more information about a topic. Theoretical models such as the PINE model (Matthes et al., 2020) and triple-path model (Wieland & Kleinen-von Königslöw, 2020) stress the importance of considering not only INE but also incidental news engagement. If researchers investigate only incidental contact with news, as has usually been the case, then they neglect all of the different possibilities that can result from those encounters. That reality might explain why results for INE, both regarding its predictors and outcomes, are rather inconclusive, if not contradictory. Studies investigating the effects of INE on knowledge in experimental settings have shown that such effects depend on engagement with the news (J. K. Lee & Kim, 2017; Nanz & Matthes, 2020). Thus, positive outcomes for dependent variables such as knowledge are only a likely outcome of INE if people are exposed to full-length information and process the information with a high level of elaboration. For that reason, in the future researchers should differentiate incidental news contact, meaning the superficial scrolling through news with low information density, from incidental news engagement, meaning exposure to full-length news that is actively processed after incidental news contact, and from even triple paths of INE (Wieland & Kleinen-von Königslöw, 2020). Doing so is relevant not only to understanding the effects of INE but also to gain more nuanced insights into its determinants. For example, understanding how INE contributes to a Matthew effect should not be considered only when the information-rich benefit from news contact to a greater extent than the information-poor but also in the context of incidental news engagement. That distinction would provide more accurate insights into dynamics caused by INE between the information-rich and information-poor, especially when based on empirical evidence.

Implication 2: improving the measurement of INE in survey studies

This review has shown that the most common way of measuring INE is with surveys using single items addressing the frequency of incidental news encounters. Participants usually have to respond to such items on a 5 – or 7-point scale ranging from never to very often (Barnidge, 2020; Heiss & Matthes, 2019b; S. Lee, 2018; Marcinkowski & Došenović, 2020; Valeriani & Vaccari, 2016). While using single items undermines the reliability of INE, the answers are also exceptionally difficult given the highly unspecific scales used. To improve the measurement of INE, a scale using several items would increase the measurement’s reliability. Although Heiss et al. (2019) have already developed a three-item scale, their scale has room for improvement. For example, all three items use a different label for (political) news. Whereas the first simply refers to news without further explanation, the second inquires into encounters with political posts made by other people in the network, while the third asks about incidental contact with political information. The labels used in the second and third items also include encounters with personal posts or political ads and thus do not refer simply to political news in a traditional sense. To overcome that drawback, a multi-item scale for INE should use the same label for news for all items and provide a definition for news along with those items. Beyond that, related to Implication 1, the measurement should consider not only several items but also different levels and/or paths of INE. Last, response options could refer to a time span that is concrete but still possible to overlook (e.g. the past week or the past 4 weeks).

Implication 3: further potential of experimental studies

The common procedure in experiments investigating INE has been to confront participants with a news feed containing news posts among other types of content in order to determine how participants engage with the posts (Kaiser et al., 2018; Kümpel, 2019a; Mothes & Ohme, 2019; Vraga et al., 2019). Arguably, however, experimental situations in which participants are instructed to scroll through a (mock) news feed are hardly comparable to situations in which people incidentally encounter news when using SNSs. That potential discrepancy also applies to the method of forced experienced sampling on smartphones (Karnowski et al., 2017), in which participants are asked to open their Facebook news feeds and read the most recent news post therein. In that procedure, participants open their Facebook apps with the specific intention to find news. That strategy precludes the circumstance of INE, in which people stumble upon news while online for reasons other than to find news. It can thus be doubted that the findings of those kinds of studies have sufficient external validity for typical situations of INE. They may also overestimate the potential of INE. By contrast, in an experimental study following a more valid procedure of simulating INE, Nanz and Matthes (2020) measured the effects of encounters that happened incidentally within their experiment. The results advanced understandings of INE by, for example, indicating that the initial goal of processing the news is not important for outcomes of INE or that learning effects depend on relevance appraisals. Other positive examples of experimental designs have used a news app (Stroud et al., 2020) or a mock Facebook group (Feezell, 2018). Both of those approaches unexpectedly confront participants with news in their everyday lives and are thus valid procedures for investigating INE. In future experimental studies, researchers should either integrate incidental encounters with news in their stimulus designs or integrate INE in the daily news diet of participants in order to study the determinants, risks, and potential of such news exposure.

Implication 4: considering the dark side of INE

Another conclusion that can be drawn from this scoping review is that when it comes to INE’s effects, most studies have investigated the positive outcomes of INE, usually from the standpoint of democracy. Thus far, most researchers have been interested in INE’s effects on knowledge and civic participation. Concerning the negative effects, studies have revealed that INE might widen gaps in knowledge between the information-rich and information-poor (Kümpel, 2020) and could reinforce selective exposure tendencies (Mothes & Ohme, 2019; Weeks et al., 2017) as well as polarization (Chen et al., 2021). However, especially regarding the latter, not much is known about the relationship between INE and polarized attitudes, which should be addressed in future studies. Other potential negative outcomes could be that INE contributes to information overload. Past studies have shown that using social media to access news can contribute to a feeling of being overwhelmed by information (Holton et al., 2012); however, the specific role of INE therein remains unclear. Other negative consequences could be that people encounter disinformation on accident, which might increase their misperceptions, false beliefs, or even trust in conspiracy theories. Although that assumption was confirmed by Borah et al. (2022) in the context of the COVID – 19 pandemic, more research that also takes a longitudinal perspective on INE and misperception is needed to confirm a causal relationship.

Implication 5: more variance between social media platforms

The descriptive analysis has shown that when researchers have focused on a specific platform to investigate INE, it is almost exclusively Facebook. That trend is understandable because Facebook remains the most important social media channel for news (Newman et al., 2020). In the future, however, researchers should investigate determinants and consequences of INE not only on Facebook but also on other social media channels. For example, S. Lee et al. (2022) have provided initial platform-dependent findings showing that INE on YouTube affected civic participation, whereas those effects did not occur for Facebook or Twitter. Moreover, recent figures indicate that WhatsApp, Instagram, and TikTok are on the rise as news channels (Newman et al., 2020), and they too have great potential to accidentally provide users with news. Even then, the news format between apps is highly different; for example, WhatsApp provides a great share of news from personal contacts, while Instagram provides news posts with longer texts and more information than Facebook. By extension, findings for INE about learning, engagement, and encounters with cross-cutting content might differ between those channels, and researchers should address those gaps in future studies.

Implication 6: taking a more holistic approach to studying INE

The published findings regarding INE clarify that its effects do not follow a clear stimulus – response logic but seem to be more complex. For example, it cannot be concluded that accidentally stumbling upon news is necessarily related to increases in knowledge or civic participation, for those findings are contingent on many different factors. Among them are the predispositions of the people who accidentally encounter news, the characteristics of the news item, and factors related to the situation and the context, as well as their interaction. Some scholars have already considered the moderating and mediating effects in INE’s relationships with different outcomes; however, the field hardly takes a holistic approach as suggested, for example, in Weeks and Lane’s (2020) model. Moreover, what has been completely ignored in empirical studies is the role of technological access. For instance, whether INE is encountered on a laptop or a mobile device alters factors related to the news content, the situations in which news encounters occur, and the personal motivation to process news. All of those factors could be considered in future research. Another contextual factor that warrants more attention is the cultural perspective. The field has a strong focus on the United States and Western Europe, whereas other regions of the world (e.g. the Global South and Eastern Europe) are heavily underexamined. That trend should be changed in the future.

Implication 7: considering initial motivations for browsing

Several theoretical papers on INE have highlighted the importance of users’ motivation for browsing in advance of INE. For example, motivation is part of Weeks and Lane’s (2020) ecological model of INE and is considered to be a factor determining incidentality in Mitchelstein et al.’s (2020) study. Furthermore, Yadamsuren and Erdelez (2011) have differentiated intention-based INE, in which people initially intend to go online for reasons other than finding news, from topic-based INE, in which people are incidentally exposed to news while looking for other news content. Although arguable that the initial motive to go online is relevant for the process and effects of INE (Matthes et al., 2020), its relevance has hardly been considered in past studies. In fact, most quantitative studies investigating INE have relied on items addressing news encounters while online for purposes other than accessing news. As a consequence, not much is known about topic-based INE or the difference between intention-based and topic-based INE. An exception has been Nanz and Matthes’s (2020) experimental study, which considered topic-based and intention-based INE as a factor in its design. Even if the findings of that study did not reveal any differences in the outcomes of INE, it might be a promising path for future research and should thus be integrated into upcoming qualitative and quantitative work on INE.

Naturally, this scoping review is not without limitations. First, I cannot be sure that my procedure to form a sample for the review was able to identify all relevant literature addressing INE. For example, I defined several word strings that had to be part of the abstracts, keywords, or titles of journal articles. As a result, I overlooked work using, for example, a description of INE in the abstract but without using the term itself. Furthermore, I considered only journal publications written in English, which might have led me to miss relevant findings published in a book chapter or in any type of literature written in a language other than English. A second limitation concerns the quantitative analysis, in which I applied a reductive approach focused on broader fields of research. Although that strategy helped to gain an overview of the primary findings, more granular trends (e.g. country-based differences, methodological reflections, and moderated and mediated effects) were only superficially touched upon, if not entirely overlooked. Thus, this scoping review should be considered as a starting point but not as a replacement for more in-depth reviews of studies on INE. Last, concerning the quantitative part of our research, the coding of the primary topic can be criticized. The categories were developed based on theoretical papers addressing INE and based on the material that was coded. Nevertheless, for some articles in our sample (16%), none of the categories matched the primary topic. Furthermore, it was only possible to code one primary topic. For most studies, that technique worked well because there was only one primary topic; however, for a couple of articles, there was more than one primary topic, including when the articles focused on several dependent variables (e.g. participation and knowledge). In those cases, the coder had to decide which topic was dominant even if such was difficult to determine. We decided to use only one primary category because different procedures caused problematic reliability values for the coding of the primary topic, but our choice nevertheless remains a limitation of that part of our analysis.

In sum, our article shows that though research on INE has come far, it remains a rather young field. Previous findings afford detailed insights into the concept of INE but also show the potential and risks of its dynamics for democracy. Even so, methodological investigations need improvement, and several gaps in the literature remain, including questions related to INE’s negative effects and the role of the specific platform or technology involved. In that light, this article illuminates many open questions that should be addressed in the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).