-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jaya Ruth Asirvatham, Julie M Jorns, How Do Pathologists in Academic Institutions Across the United States and Canada Evaluate Sentinel Lymph Nodes in Breast Cancer? A Practice Survey, American Journal of Clinical Pathology, Volume 156, Issue 6, December 2021, Pages 980–988, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqab055

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

There are little data on how changes in the clinical management of axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer have influenced pathologist evaluation of sentinel lymph nodes.

A 14-question survey was sent to Canadian and US breast pathologists at academic institutions (AIs).

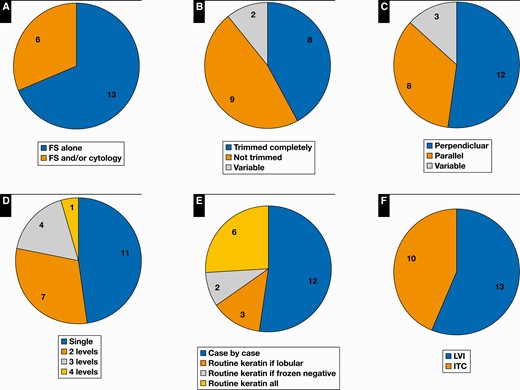

Pathologists from 23 AIs responded. Intraoperative evaluation (IOE) is performed for selected cases in 9 AIs, for almost all in 10, and not performed in 4. Thirteen use frozen sections (FSs) alone. During IOE, perinodal fat is completely trimmed in 8, not trimmed in 9, and variable in 2. For FS, in 12 the entire node is submitted at 2-mm intervals. Preferred plane of sectioning is parallel to the long axis in 8 and perpendicular in 12. In 11, a single H&E slide is obtained, whereas 12 opt for multiple levels. In 11, cytokeratin is obtained if necessary, and immunostains are routine in 10. Thirteen consider tumor cells in pericapsular lymphatics as lymphovascular invasion (LVI), and 10 consider it isolated tumor cells (ITCs).

There is dichotomy in practice with near-equal support for routine vs case-by-case multilevel/immunostain evaluation, perpendicular vs parallel sectioning, complete vs incomplete fat removal, and tumor in pericapsular lymphatics as LVI vs ITCs.

Clinical trials have variably changed pathologist practice in evaluating breast sentinel lymph nodes in academic institutions.

There are areas of uniformity and dichotomy in the evaluation of breast sentinel lymph nodes; the latter may affect subsequent clinical management.

The trend toward more conservative clinical management is reflected in a similar trend of less extensive breast sentinel lymph node evaluation in some academic institutions.

In recent years, there has been significant evolution in the management of axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer. For decades, axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), a procedure associated with significant long-term complications affecting quality of life, was the only available procedure to determine regional lymph node status. The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-32 randomized prospective clinical trial established sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy to be a safe alternative to ALND, demonstrating equivalence in patients with early stage, clinically node-negative, disease.1 Recent trials such as IBCSG 23-01, ACOSOG Z0011, and AMAROS show that ALND may be safely omitted in selected clinically node-negative patients with metastatic carcinoma limited to two or fewer SLNs.2-4 As a result, some experts have advocated for less extensive pathologic evaluation of SLN, but there are little data on how evolution to a more conservative clinical approach has affected routine pathology practice.5,6 We sought to examine SLN pathology practices among academic breast pathologists in the United States and Canada.

Materials and Methods

A 14-question multiple-choice type survey was sent to 33 US and 11 Canadian breast pathologists at 44 academic institutions between August and September 2019. Five questions related to intraoperative evaluation (IOE) of SLNs and 9 questions related to evaluation of permanent sections. The questions were as follows:

Is IOE of SLN for breast cancer performed at your institution?

If yes, how do you perform IOE?

If you perform cytologic examination, what method do you use?

If you perform frozen section (FS), is fat trimmed?

If you perform FS, how is the node processed?

From permanent section (PS), do you obtain single or multiple levels?

If multiple, how many are cut?

If multiple, how many are stained with H&E?

At what interval do perform serial sectioning (in microns)?

Do you obtain cytokeratin stains?

Which cytokeratin stains do you prefer?

For nonsentinel axillary lymph nodes that are grossly negative, how do process for PS?

How would you interpret tumor cells in the pericapsular lymphatic spaces?

Do you document the extent of extranodal extension in your report?

Results

Five Canadian and 18 US pathologists responded (total 23; see Acknowledgments and Supplement 1 for details; all supplemental materials can be found at American Journal of Clinical Pathology online).

Frequency of IOE of SLNs

Intraoperative consultation was requested on almost all SLNs in 10 (43.5%) institutions. In nine (39.1%) institutions, IOE of SLN was only requested in selected cases (such as patients undergoing mastectomy, post-neoadjuvant cases, patients who did not meet ACOSOG Z11 criteria) Figure 1A. In four (17.4%) institutions, three of which were Canadian, there were no requests for IOE of SLN.

A, Nearly half the institutions surveyed reported intraoperative consults only for selected cases. B-E, Demonstrates areas of dichotomy in pathology practice. B, Fat processing during intraoperative evaluation. C, Plane of sectioning. D, Permanent H&E levels. E, Keratin immunohistochemistry. F, Tumor in pericapsular lymphatic space. FS, frozen section; ITC, isolated tumor cell; LVI, lymphovascular invasion.

Comments

“The surgeons only freeze SLN for post neoadjuvant patients.”

“Done in about 60% of cases. In other cases breast surgeons opt not to ask for frozen.”

“Routinely done, even for patients meeting Z11 criteria, our surgeons are still requesting frozen, although we have a carepath that states there doesn’t need to be an FS.”

“We do NOT perform frozen on SLN if it is a clinically negative node and patient is having lumpectomy for invasive carcinoma. Inpatients with clinically positive nodes or known positive node; most get some type of neoadjuvant therapy and in those cases we do frozen on SLN. In patients with known positive nodes, as most have this biopsied and diagnosed before surgery, then there is no need for FS. For almost all patients with invasive carcinoma, or large DCIS [ductal carcinoma in situ] (generally over 5 cm) having mastectomy, we do FS on SLN. Our institution follows Z11 criteria. These are general principles but of course exceptions exist.”

“FS is done for most DCIS patients undergoing mastectomy and for Alliance A011202 trial or similar patients (post-neoadjuvant chemotherapy with known axillary metastasis prior to therapy).”

“Only done in the setting of mastectomy for known ipsilateral invasive carcinoma without neoadjuvant chemotherapy.”

“Our surgeons have not asked to implement this practice.”

“Not anymore. Used to be by cytology touch prep. Rarely now for a large, suspicious node.”

“Only perform for cases with clinically the node is felt to be grossly positive. If obviously positive only a representative section is frozen.”

“Yes, for post neoadjuvant and mastectomy.”

“Our surgeons never send sentinel lymph node for intraoperative consultation.”

“Our surgeons feel comfortable waiting for final diagnosis on permanent sections.”

“Mostly for mastectomy, after neoadjuvant, etc., not routinely done for BCS/Z11 patients.”

Method of IOE

Of 19 institutions where intraoperative assessments are requested, the most common method of evaluation is using FS alone (13; 68.4%). In six institutions, FS and/or cytologic techniques are used (four imprints/touch preparation [TP], one smear, and one either, depending on pathologist preference). In one institution, the preference is for cytology (TP), except for post-neoadjuvant chemotherapy cases, where FS is used.

Comments

“FS, C [cytologic] or both—with recommendations from the breast service that frozens are preferred in post neoadjuvant cases, cases with scant atypical cells on touch prep or lobular cancers.”

“Touch prep, except in NAC [neoadjuvant chemotherapy] treated patients where I prefer FS.”

“Pathologist preference but predominantly FS > 95%.”

Gross Evaluation of SLNs and Non-SLNs

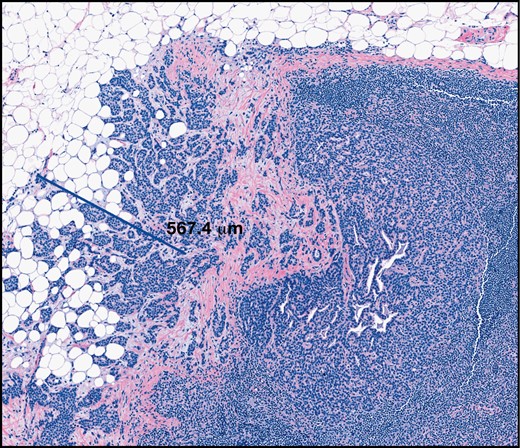

During intraoperative evaluation, a sleeve of perinodal fat is retained (fat not completely trimmed) in nine (47.4%) institutions, for evaluation of extranodal extension Figure 1B and Figure 2. In eight (42.1%) institutions, the fat is completely trimmed. In two (10.5%) institutions, the practice is variable—trimmed fat is submitted for evaluation for extranodal extension for permanent sections in one institution. In 12 (52.2%) institutions, the entire node is submitted, usually sectioned at 2-mm intervals. Practice is variable in the others. The preferred plane of sectioning is perpendicular to the long axis in 12 (52.2%) institutions, parallel to the long axis in 8 (34.8%) institutions, and variable in 3 (13%) institutions Figure 1C and Figure 3. In all 23 institutions, non-SLNs are entirely processed at 2 mm.

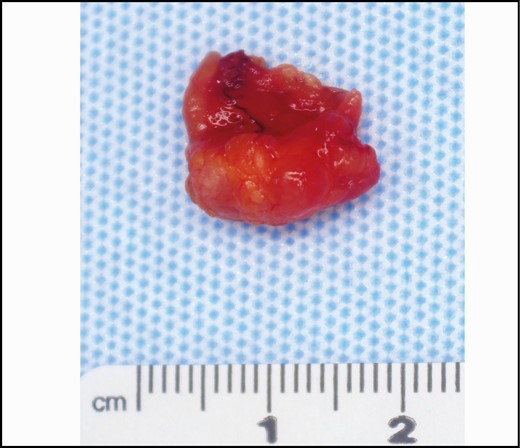

Gross image. Lymph node with surrounding adipose tissue. Gross extranodal extension is generally an indication for axillary lymph node dissection.

Gross image. Two lymph nodes of near-equal size sectioned perpendicular to the long axis (left) and parallel to long axis (right).

Comments

“As much fat is trimmed as possible.”

“Fat is trimmed as best as possible.”

“As much fat as possible is trimmed away if peels off easily. If adherent and worrisome for extranodal extension, this is submitted. Any trimmed tissue is submitted for permanent sections.”

“Fat is either trimmed or lipid is removed by gentle rolling the lymph node on a paper towel or similar material.”

“Depends on the setting and size of node. Smaller nodes are bisected, larger ones breadloafed at 2 mm intervals perpendicular to long axis. Gross assessment is performed, if suspicious areas are seen, these are submitted, otherwise 1-2 of the largest sections are processed for FS and the remainder is fixed and processed routine FFPE [formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded].”

“We freeze all nodes entirely when we do FS—typically bisected, freeze both halves, but if very large may need to try to trisect or serially section at 2 mm intervals etc. and if very small just put on whole.”

“Bisected trisected or more—whatever necessary to freeze entirely, at least bisected unless tiny.”

“Sections such that 2 mm intervals are used; if we can achieve that by bivalving that is preferred.”

“For non-sentinel nodes, we always put in all nodal tissue but the way we section it depends on the node size—may breadloaf at 2 mm intervals or bisect—I do not think we have one set way of doing it other than to make sure all nodal tissue is submitted.”

“Bisect and submit both halves, unless too big, then serial section and submit at 2 mm intervals.”

“We process half and save half for permanents. We serially section/breadloaf the node at 2 mm intervals, inspect for any grossly suspicious areas, and submit half of the node for frozen section (to include any grossly suspicious areas), and then submit remainder for permanents.”

“Usually the node is sampled in toto at 2 mm intervals but not for gross metastatic disease were representative section is submitted.”

H&E Evaluation

In 11 (47.8%) academic institutions, only a single H&E slide is obtained from the FFPE block. In 12 (52.2%) institutions, multilevel evaluation is performed Figure 1D. Two H&E levels appear to be the most common practice (seven institutions). In four institutions, three H&E levels are obtained, and in one institution, four H&E levels are obtained. In six institutions, the levels are between 1 and 10 μm deep. The levels are between 10 and 15 μm deep in three institutions and between 100 and 200 μm deep in two institutions. In one institution, the depth of evaluation was not specified.

Comments

“Single H&E levels, with additional levels on an as-needed basis, typically 2 or 3 levels with all levels stained.”

“We do not perform intraoperative consult on sentinel lymph nodes. We assess an initial H&E first. After assessing it, 3 H&E and CAM 5.2 and AE1/AE3 are requested if there is no obvious tumor.”

“Microns may very between levels. We do not have a set guideline for our histotechs.”

Use of Immunohistochemistry

In 12 (52.2%) institutions, a cytokeratin immunohistochemical stain is obtained if necessary on a case-by-case basis (if suspicious cells identified, lobular morphology noted, or following neoadjuvant therapy). Routine keratin immunohistochemistry is obtained in 11 (47.8%) academic institutions Figure 1E. In three institutions, routine immunohistochemistry is only obtained in cases of lobular carcinoma and/or following neoadjuvant therapy and in two institutions only if the frozen section is negative for carcinoma. Cytokeratin AE1/AE3 is the favored immunostain (18 institutions, 78.3%). In three institutions, both cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and CAM 5.2 are evaluated.

Comments

“Cytokeratin immunostain is obtained on the case-by-case basis at the discretion of the pathologist.”

“Pathologists order on or lobular carcinoma and neoadjuvant cases when no mets are seen on the initial section.”

“Yes, routinely unless the node was positive on FS, then no cytokeratin.”

“We almost never obtain cytokeratin stains. If needed to evaluate atypical cells we do it.”

“Only if suspicious cells are seen that are not obviously carcinoma—usually if treatment effect present and deciding if histiocytes or carcinoma, sometimes do with lobular cases if questionable cells present.”

“I know a lot of institutions in the New York City area are not doing routine cytokeratins on SLN and I understand the rationale in many instances is because the significance of detection of ITC [isolated tumor cell] has not been clearly demonstrated. We however continue to do them and the clinicians do factor this information into the decision making in some cases.”

“Very rarely, only in very few post neoadjuvant cases with treatment effect and rare atypical cells or histiocytoid invasive lobular carcinoma.”

“Cytokeratin is only routinely performed on sentinel lymph node for invasive lobular carcinoma.”

Challenges in Interpretation

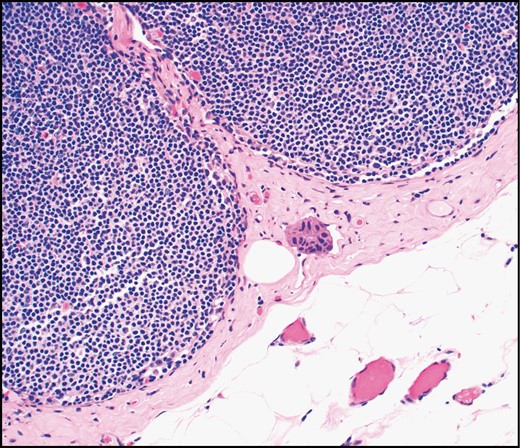

Twenty-one (91.3%) pathologists document the extent of extranodal extension (two qualitatively) Figure 4. Thirteen (56.5%) pathologists would interpret tumor cells in the pericapsular lymphatic space as lymphovascular invasion, and 10 (43.5%) would interpret them as isolated tumor cells Figure 1F and Figure 5.

Extent of extranodal extension (H&E, ×6). Extranodal extension is emerging as a predictor of non–sentinel lymph node involvement and may be an indication for axillary lymph node dissection.

Tumor cells in pericapsular lymphatic spaces are variably interpreted as lymphovascular invasion or isolated tumor cells (H&E, ×20).

Comments

“Extranodal extension. We will usually make a comment if it is focal.”

“Extranodal extension. Just state present or absent.”

“Extranodal extension. Only to note if ‘focal’ or ‘extensive’ but no set criteria for each.”

“Extranodal extension. Yes, but only qualitatively as ‘focal’ or ‘extensive’ per request of radiation oncologists.”

“Provide #mm of greatest extent.”

“Isolated tumor cells. This is still unclear to me, but per CAP [College of American Pathologists] guidelines, I classified these as metastatic. I will perform levels to see if tumor cells show up in the parenchyma but most of the time this does not help.”

“If tumor is in cap/pseudosubcapsular or extends into cap from outside I considered a positive node and based on size it is ITC, micromet, etc. If all tumor is entirely in a lymphatic space which does not enter any part of the node, I consider it LVI [lymphovascular invasion].”

“I consider it as ITC, but I know some other pathologists in my institute consider it as LVI.”

“It depends, if within the lymph node capsule, consider isolated tumor cells. But if outside the lymph node capsule in the perinodal adipose tissue consider LVI.”

Other Comments

“We have tried to standardize across a healthcare system so that lymph nodes removed in hospital ‘Y’ will be handled the same way as lymph nodes removed in hospital ‘Z.’ Not perfect, but more standardized than we were 3 years ago.”

“Most of the frozens are for post-NAC patients that are clinically node-negative after chemo (no longer palpable). Our surgeons submit at least 3 lymph nodes in post-NAC patients. We also mention if treatment effect is present, if clearly present.”

“Our surgeons still ask for a lot of intraoperative consultation. It would be great if there were consensus guidelines that we could point to when this is clearly indicated. The main point of intraoperative consultation in this setting is to find obviously positive lymph nodes at this point (not detect micromets or ITCs)—so even moving to gross evaluation with TP or frozen on suspicious nodes may be a relevant way to go. We need more data on what to do post neoadjuvant though.”

Discussion

Our study identified four areas of uniformity and four areas of dichotomy in the evaluation of SLNs among academic breast pathologists in North America. In our study, IOE was performed for all cases in 10 academic institutions. In almost an equal number of institutions, the frequency of FS was limited to select cases (in general, those who did not meet ACOSOG Z0011 criteria), in an attempt to omit ALND.

The key question of the ACOSOG Z0011 clinical trial was whether ALND improved survival or local control compared with observation in patients with clinically node-negative (cN0), early stage (T1-T2, tumor size ≤5 cm) breast cancer with one to two positive SLNs undergoing breast-conserving therapy. The trial included 856 women with median follow-up of 9.3 years and demonstrated that in this group of patients, SLN was not inferior to ALND.1 Trial exclusion criteria included mastectomy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT), partial or no radiation, palpable adenopathy or gross extranodal disease, more than three positive SLNs, matted nodes, and metastasis identified by immunohistochemistry (IHC). Recent studies have shown that the impact of the ACOSOG Z0011 clinical trial has been a decrease in the frequency of IOE and ALND.7-9

In most academic institutions, FS is the preferred method of IOE. Per current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, if the patient is clinically node negative at the time of diagnosis, and the SLN demonstrates only micrometastasis or isolated tumor cells, no further axillary surgery is required, even in patients who do not meet the ACOSOG Z0011 criteria. Hence, cytologic techniques, which cannot determine the size of metastasis, may not be an appropriate form of evaluation for this group of patients.

Extranodal extension (ENE) is an emerging predictor of tumor involvement of nonsentinel nodes.10-12 In a meta-analysis, ENE was associated with a higher risk of mortality (relative risk [RR], 2.51; 95% CI, 1.66-3.79, P < .0001) and recurrence (RR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.38-3.10, P < .0001).10 In the ACOSOG Z0011 trial, patients with gross ENE were excluded, and the presence of microscopic ENE was not evaluated. Recent studies have shown that the presence and extent of ENE significantly correlated with nodal tumor burden, suggesting that greater than 2 mm of ENE may be an indication for ALND or radiotherapy when applying ACOSOG Z0011 criteria to patients with one to two positive lymph nodes. Choi et al11 evaluated the impact of the size of ENE (less than or greater than 2 mm) in patients meeting ACOSOG Z0011 criteria and found in a study of 208 patients that ENE on SLN is associated with N2 disease. Despite the increased nodal burden, ENE 2 mm or smaller was associated with recurrence and survival rates similar to those of patients with no ENE. Hence, evaluation of ENE at FS has implications for subsequent treatment. Most study respondents indicated that fat around the lymph node was not completely trimmed. In one institution, the trimmed tissue was separately submitted for evaluation at permanent sections. However, in most surveyed institutions, the presence of ENE was documented after evaluation of permanent sections.

The most common practice was to submit the entire SLN for IOE after sectioning at 2-mm intervals, similar to processing for permanent sections. This is in keeping with grossing protocols outlined by both the CAP and Royal College of Pathologists (RCPath) designed to identify all macrometastases (>2 mm).13,14 Careful gross and microscopic evaluation is necessary to determine if patients meet criteria for conservative management. In the NSABP B-32 clinical trial, participating sites were instructed to slice SLN at 2-mm intervals, embed all tissue in paraffin blocks, and examine one H&E section from each block, with goal of identifying (or not missing) macrometastasis.15 In some institutions, due to potential loss of tissue during FS and/or challenges in obtaining an appropriate section of fatty tissue, only a representative sample is submitted (bisected with both halves submitted for FS and later sectioned at 2-mm intervals for permanents, bisected with one half submitted at 2-mm intervals for FS and the other half reserved for PS, grossly suspicious foci, or one or two larger sections of lymph node with no overt metastatic disease). In all institutions, non-SLNs are sectioned at 2-mm intervals and entirely submitted for PS.

One area of dichotomy in practice was parallel vs perpendicular sectioning of the lymph node. Per current CAP guidelines, “the node is to be sectioned at 2mm intervals along the long axis.” 13 This is a new recommendation in the most recent guidelines and not present in prior iterations, in which a recommendation for sectioning at 2-mm intervals without further instruction is provided.16 In contrast, RCPath recommendations outline sectioning at 2-mm intervals perpendicular to the long axis.14 Relatively recent CAP updates and conflicting recommendations, coupled with individual and institutional preference, likely resulted in the split in survey responses, with 12 institutions opting for perpendicular, 8 parallel, and 3 variable sectioning in relationship to the long axis of the SLN. Some experts recommend sectioning the node parallel to the longest axis, as it produces fewer slices to examine, and old anatomic data suggest that afferent lymphatics are more likely to enter the lymph node in this plane.15 They also note that the plane may be difficult to determine, and what is important is ensuring that no slice is thicker than 2 mm, at least one microscopic section is examined every 2 mm, and there is the likelihood of detecting all metastases larger than 2 mm. However, others have suggested that perpendicular sectioning more accurately identifies small SLN metastasis.17

Another area of dichotomy in practice was the routine use of multiple levels and cytokeratin stains. In the NSABP B-32 trial, while treatment decisions were based on findings in the initial H&E SLN section, SLN blocks from patients who were negative on the initial H&E were submitted for H&E and cytokeratin stains at a 0.5-mm and 1-mm depth into the block, which resulted in identifying occult metastasis (ITCs and micrometastatic disease not immediately apparent on initial H&E sections) in 15.9% of patients (11% ITC, 4% micrometastasis).18 Five- and 10-year follow-up of patients with and without occult metastases were statistically significant, but the percent increase in overall and disease-free survival (DFS) and distant disease-free interval was minimal (DFS, 86.4 vs 89.2%; overall survival, 94.6% vs 95.8%). In addition, the ACOSOG Z0010 trial demonstrated that in women undergoing breast-conserving therapy and SLN biopsy, IHC evidence of SLN involvement was not associated with decreased overall survival. In this study, which included 5,119 patients, there was no axillary-specific treatment for H&E-negative SLNs, and clinicians were blinded to IHC results.19 As additional evaluation does not appear to translate into clinical benefit, the American Society of Clinical Oncology and NCCN do not recommend routine immunostains.20,21 Other international organizations, such as the National Health Service Breast Screening Program and RCPath, also do not advocate routine use of enhanced methods.14

We also identified variability in the interpretation of tumor in pericapsular lymphatic spaces. While some pathologists identified these as lymphovascular emboli, others interpreted these as ITCs. While ITCs are not included in the total number of positive nodes for N classification, in SLN after NACT, there are currently no data to enable axillary dissection to be safely omitted, irrespective of the size of the SLN metastasis.22,23 An evaluation of 181 patients with post-NACT who had a residual positive lymph node irrespective of the method of detection (17% [1/6] with isolated tumor cells, 64% with micrometastasis, and 62% with macrometastasis) also had additional non-SLN involvement at ALND.24 The currently accruing Alliance A011202 trial, which randomizes patients with persistent positive axillary disease following NACT to axillary radiation with or without ALND, aims to determine if ALND can be safely omitted in this population.25

In conclusion, recent clinical trials have changed axillary management in breast carcinoma toward a more conservative approach. These changes have resulted in decreased utilization of IOE at most institutions. The variation in pathology practice may be driven by variations in surgical practice or expectations of the surgical team. Among pathologists in academic institutions, there are areas of uniformity in practice (preference for FS during IOE, sectioning lymph nodes at 2 mm, submitting the entire lymph node for FS, and documenting ENE after evaluation of permanent section) and areas of dichotomy in practice (complete vs incomplete removal of perinodal fat at FS, perpendicular vs parallel sectioning, routine vs case-by-case multilevel H&E/immunostain examination, and interpretation of tumor in pericapsular lymphatics as LVI or ITC). Data-driven efforts to increase standardization of SLN pathologic evaluation should be undertaken. Additional data on reporting of ENE (for both IOE and permanent section evaluation), plane of gross sectioning, and cost vs benefit for multilevel sectioning best target remaining questions that will help guide development of best practices.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following pathologists for their expertise and for taking the time to respond to the survey: Kimberly Allison, MD, Stanford University; Gillian Bethune, MD, Dalhousie University; Tawfiqul Bhuiya, MD, Hofstra University; Ira BleiweissMDUniversity of Pennsylvania; Ashley Cimino-Mathews, MD, Johns Hopkins University; Timothy D’Alfonso, MD, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; Erinn Downs-Kelly, DO, Cleveland Clinic; Susan Fineberg, MD, Montefiore Medical Center; Carmen Gomez, MD, University of Miami; Jose A Gomez, Western University; Hua Guo, MD, Columbia University; Syed Hoda, MD, Cornell University; Shabnam Jaffer, MD, Mount Sinai School of Medicine; Sonali Lanjewar, MD, University of Tennessee; Belinda Lategan, MD, University of Mannitoba; Xiaoxian (Bill) Li, MD, Emory University; Chieh-Yu Lin, MD, Washington University School of Medicine; Kristen Muller, DO, Dartmouth-Hitchcock; Sandip SenGupta, Queens University; Gary Tozbakian, MD, Ohio State University; and Philip Williams, McMaster University.

This research was presented in part at the United States & Canadian Academy of Pathology 109th Annual Meeting; March 2, 2020; Los Angeles, CA. The survey was conducted while J. R. Asirvatham was affiliated with the University of Florida, Gainesville.

References